The Measurement of the Diversity in Learning to Enhance Educational Inclusion and Achievement. Validation of a Scale in Higher Education

[La medición de la diversidad en el aprendizaje para mejorar la inclusión y el desempeño educativo. La validación de una escala en la Educación Superior]

Miguel A. Gandarillas1, María N. Elvira-Zorzo2, Iria Osa-Subtil3, Montserrat Rodríguez-Vera4, and Fernando Chacón-Fuertes1

1Complutense University of Madrid - UCM, Spain; 2University of Salamanca, Spain; 3Universidad Europea de Madrid, Spain; 4Universidad San Sebastián – USS –, Concepción, Chile

https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2025a14

Received 7 March 2024, Accepted 11 February 2025

Abstract

There is an increasing focus among researchers and educators on diversity in learning patterns (DinL) in the classroom. However, there is a lack of comprehensive frameworks, considering psychosocial factors crucial for inclusion and equality. This study aims to develop and validate an integrative construct of DinL to address this gap. A scale was built measuring the five dimensions of the construct: Coping with Difficulties, Effort, Autonomy, Understanding/Career Interest, and Social/Physical Context. To validate the scale, a study was carried out with a sample of 1,644 students from Complutense University of Madrid, analysing the DinL factorial structure, internal consistency, and validity. Results showed robust internal and external validity, with good values for configural, metric, invariance, and scalar variance. Significant relationships were found between DinL factors, academic performance, and sex. In conclusion, this study offers an optimal scale to assess DinL in the classroom for personalized education, psychosocial inclusion, and equality.

Resumen

Existe un creciente interés entre investigadores y educadores sobre la diversidad en los patrones de aprendizaje (DenA) en el aula. Sin embargo, falta un marco integral que también considere los factores psicosociales cruciales para la inclusión y la igualdad. Este estudio tiene como objetivo desarrollar y validar un constructo integrador de DenA para abordar esta necesidad. Se construyó una escala para medir las cinco dimensiones que comprenden el constructo: Afrontamiento de Dificultades, Esfuerzo, Autonomía, Comprensión/Interés Profesional, y Contexto Social/Físico. Para validar la escala, se realizó un estudio con una muestra de 1,644 estudiantes de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, analizando la estructura factorial de DenA, la consistencia interna y la validez. Los resultados mostraron una validez interna y externa robusta, con buenos valores para la varianza configuracional, métrica, escalar, e invariancia. Se encontraron relaciones significativas entre los factores de DenA, el rendimiento académico y el sexo. En conclusión, este estudio ofrece una escala óptima para evaluar DenA en el aula para una educación personalizada que favorezca la inclusión psicosocial y la igualdad.

Palabras clave

Diversidad en el aprendizaje, EducaciĂłn superior, EducaciĂłn inclusiva, Aprendizaje colaborativo, Salud mental y bienestar, InnovaciĂłn educativaKeywords

Diversity in learning, Higher education, Inclusive education, Collaborative learning, Mental health and well-being, Educational innovationCite this article as: Gandarillas, M. A., Elvira-Zorzo, M. N., Osa-Subtil, I., Rodríguez-Vera, M., and Chacón-Fuertes, F. (2025). The Measurement of the Diversity in Learning to Enhance Educational Inclusion and Achievement. Validation of a Scale in Higher Education. PsicologĂa Educativa, 31(2), 111 - 120. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2025a14

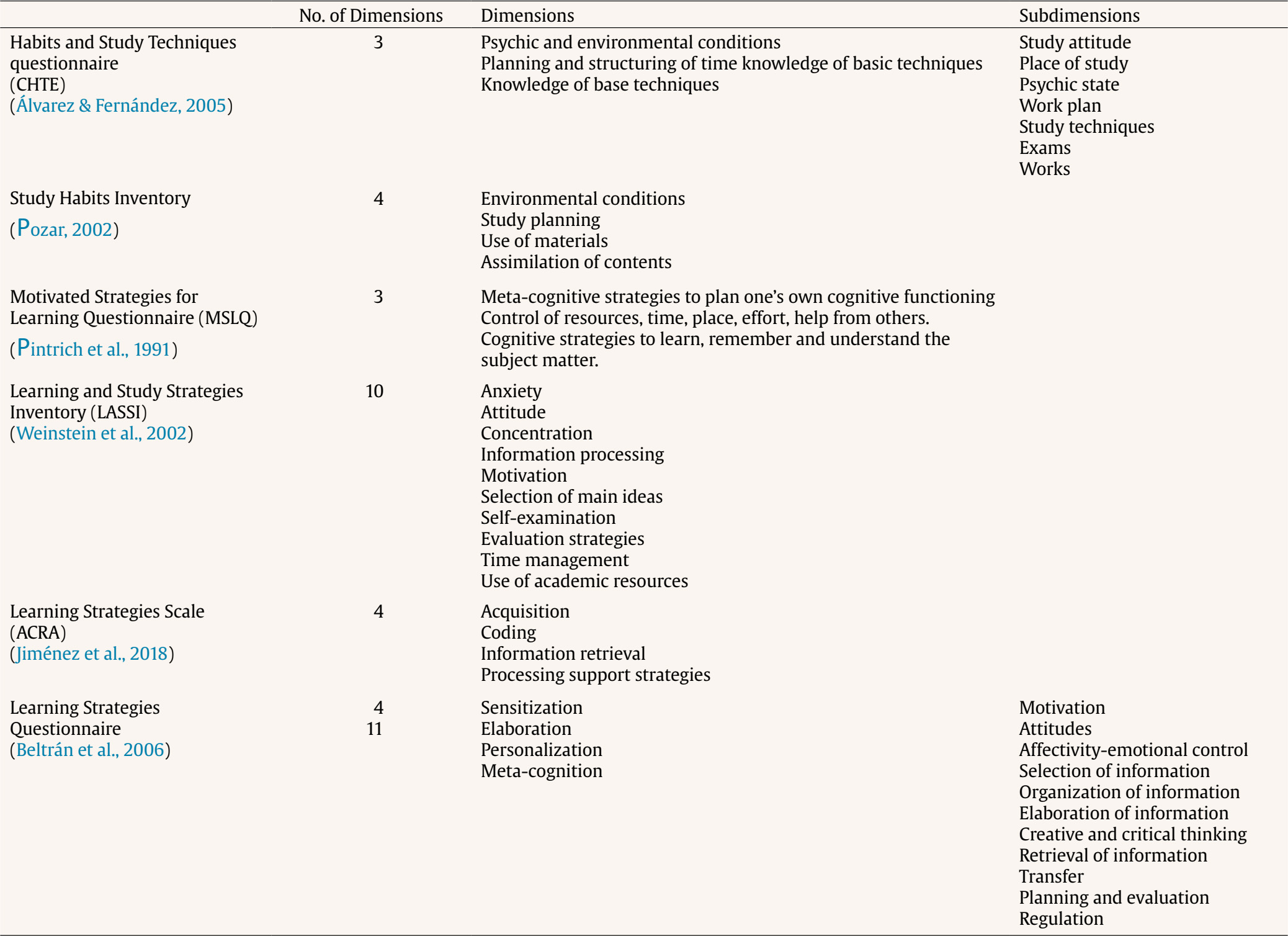

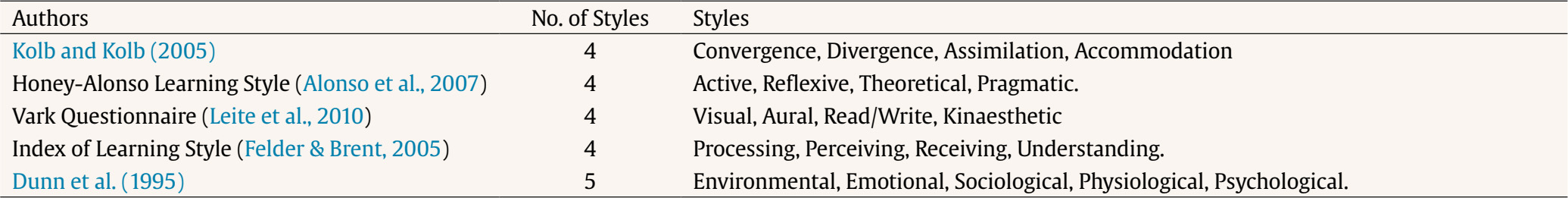

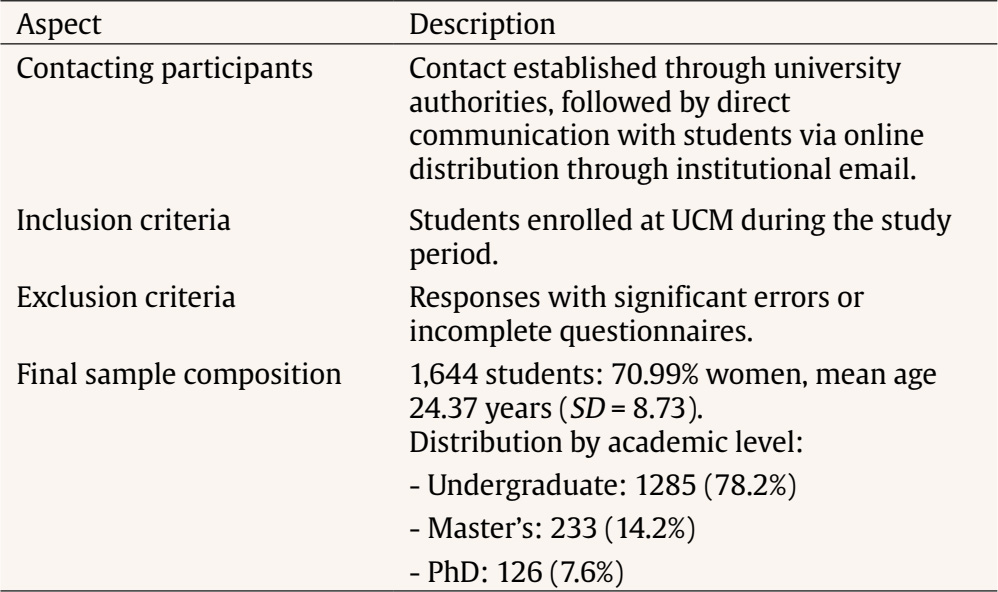

Correspondence: mgandari@ucm.es (M. Á. Gandarillas).The growing interest in studying the diversity of learning patterns in the university context arises from the motivation of professors to foster a mutual adaptation between their educational goals and the rising diversity of students in the classroom. This diversity encompasses significant differences in psycho-educational, social, and contextual characteristics. Research literature highlights the importance of addressing this diversity in learning styles, habits, strategies, and psychosocial difficulties (DinL), as it serves as a fundamental resource for collaborative group learning, promoting social and cultural inclusion and equality (Fuentes et al., 2021; Lardy et al., 2022; Manion et al., 2020; Rodríguez-Hidalgo et al., 2021; Rojo-Ramos et al., 2021). Differentiated learning approaches enhance personalized education, catering to diverse learning needs and fostering the development of learning strategies throughout university education (Hengesteg et al., 2021; Ismail & Aziz., 2019; Solari et al., 2022; Pozas et al., 2020). Addressing educational diversity and performance heterogeneity in collaborative learning environments can foster creativity, innovation, and cognitive flexibility (Dotzel et al., 2022; Lu et al., 2021; Schubert & Tavassoli, 2020), while also supporting the educational needs of students with high abilities (Fernández-Díez et al., 2017). In this context, it is also essential to consider the significant impact of global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which has sped up the variety of educational models and tools, impacting the students’ well-being as well as their learning strategies. This has made the study of DinL even more pertinent, as it has highlighted the need for more adaptive, inclusive and egalitarian approaches to university teaching. An aim of this study is the theoretical and empirical building of DinL as a construct. The relevant research literature regarding related concepts that preceded this construct is briefly described next. Despite the increasing number of studies focusing on DinL, the literature in this field remains fragmented, employing diverse approaches, terminologies and measuring tools, which complicates its research and application. Learning styles (LS), study habits, learning strategies, along with different types of learning difficulties are terms and issues traditionally approached in fields related to DinL. Regarding LS, Table 1 gathers some of the most important studies on this concept. According to Medina & Medina (2012), LS are defined as the preferences that a person has for specific types of selection, perception and understanding of information. Relevant authors in the study of LS grounded the definition of different taxonomies on theoretical models. There is no consensus about the concept of LS partly because most theoretical approaches focus on different fields or areas of learning, showing disagreements on what main relevant dimensions to measure in the variety of different LS scales (e.g., Acevedo et al., 2009; Alonso-Martín et al., 2021; Bilbao et al., 2021; Herrera & Rodríguez, 2011; Mehenaoui et al., 2022; Muñoz-Mederos, 2021; Razzaque et al., 2021; Said et al., 2010). Research on study habits is closely linked to that of LS. The scales on study habits are usually more oriented towards secondary education students (12-18 years old). Learning strategies differ from LS and study habits as they imply the presence of an organization and planning system of learning methods and tools aimed at a good academic performance (Escanero-Marcén et al., 2018; Maya et al., 2021; Pashler et al., 2008; Shum, 2021; Song & Vermunt, 2021). Table 2 collects a summary of the main dimensions included in questionnaires and scales on learning habits and strategies, showing a variety of approaches and concepts. Table 2 Definition of the Different Learning Dimensions Based on Major Scales and Questionnaires on Learning Habits and Strategies   Note. Source: Own elaboration Cognitive and emotional difficulties in university learning have little presence in the studies on learning styles, habits, and strategies. Nevertheless, there is a continuous increase in the number of studies on mental health and psychosocial problems in university students, showing a growing concern about it. Such studies focus on issues such as anxiety, depression, demotivation, attentional deficits, and family and social stressors in the learning process (e.g., Asante & Andoh-Arthur, 2015; Bernard et al., 2024; Brenneisen et al., 2016; Cheng et al., 2016; Conley et al., 2023; Dumitrescu & De Caluwé, 2024; Ibrahim et al., 2013; January et al., 2018; Lamis et al., 2016; Lew et al., 2019; Martos et al., 2023; Melo et al., 2021; Mirza et al., 2021; Naser et al., 2022; Pozos et al., 2015; Samaniego & Buenahora, 2016; Tan et al., 2023; Tholen et al., 2022; Tian-Ci Quek et al., 2019; Trunce et al., 2020; Ya et al., 2024), pointing in many cases to the need to be addressed using inclusive approaches. The incorporation of these issues is fundamental in establishing an inclusive concept of DinL. As a conclusion of these studies on learning styles, habits, strategies, and psychosocial difficulties, scientific literature provides a deep and useful field of knowledge in the Higher Education context. However, most of the above studies are based on approaches that are reduced in their focus of study (for instance, in the stages of the learning cognitive process or in the perceptive modes). Often, they follow theoretical models with a narrow scope which may not fully encompass the above-mentioned concepts on LS, habits, strategies and difficulties. This may also result in a lack of external and ecological validity, thereby complicating the task of comprehending DinL within its psychosocial context with the objective of fostering inclusion and equality in higher education. The marked difference in models and tools, with little relationship among them (see, for example, Tables 1 and 2), may explain the difficulties encountered in applying the tools (scales) to key factors such as academic performance and psychosocial influences (Escanero-Marcén et al., 2018; Pashler et al., 2008). This large disagreement among studies makes the work of the educator and researcher studying DinL more challenging when it comes to getting a more personalized and inclusive teaching-learning process. Moreover, these approaches and models complicate the identification and mitigation of the psychosocial and contextual factors influencing the learning process, if the objective is to enhance learning performance and academic inclusion and equality. There is a need to go beyond the traditional approaches into an integrative DinL construct sensitive to its relationship with those factors (such as child-rearing practices, family socio-economic levels, the educational levels of parents, school methodologies during elementary and high school, gender differences, or cultural background) due to the strong evidence of their relevance on academic variables (e.g., Aliberti et al., 2019; Arcay et al., 2019; Batool, 2020; Bully et al., 2019; Casad et al., 2017; Fortin et al., 2015; Herrera et al., 2020; Hofhuis et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2020; Masud et al., 2019; Moral-García et al., 2020; Njega et al., 2019; Rodríguez-Hernández et al., 2020; Silva-Laya et al., 2020; Soria-Duarte, 2019; Spinath et al., 2014; Steinmayr & Kessels, 2017; Tinajero et al., 2020; Van Hek et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2022). Such progress is critical to achieving effective inclusive education (Shaeffer, 2019). To do so, there is a need to have reliable tools to assess this DinL in the classroom. The present study focuses on analysing and validating the psychometric properties of a scale designed to measure an integrative DinL construct. DinL is here defined as the different psychological processes, styles, habits, difficulties, internal and external resources, and contextual and psychosocial factors that build the heterogeneous set of learning patterns of the students’ group in a classroom. This comprehensive DinL construct allows for a broader approach, encompassing the main components and dimensions that define, assess, and explain the diverse learning methods of students in the classroom. This perspective emphasizes university teaching that acknowledges and accommodates this diversity, fostering educational inclusivity as a resource for collaborative learning. Dimensions of Diversity in Learning Grounded on the literature on the related fields (mentioned above) and our preliminary studies, DinL is defined based on a set of learning dimensions, each dimension representing a psycho-social-educational way to process information. The learning profiles comprising the combination of different levels of such dimensions will allow us to determine the learning characteristics of the student from an integrative approach. The set of different types of DinL profiles among students will define the DinL in a specific classroom. Five key learning dimensions composing the DinL construct are defined, according to the literature research in these fields: (1) Coping with Difficulties, understood as the level of optimal regulation of emotional and psychosocial difficulties in learning such as anxiety, nervousness, bad mood, irritability, impulse control, attention deficits, apathy, discouragement, success expectations instudy, difficulties at home and university, the attribution of success or failure to circumstances, self-esteem, and the learning climate in the class (e.g., Alves et al., 2007; Bernard et al., 2024; Conley et al., 2023; Del Valle et al., 2020; Dumitrescu & De Caluwé, 2024; Herrera et al., 2020; Heritage et al., 2023; Khalil et al., 2020; Lew et al., 2019; MacCann, et al., 2020; Martos et al., 2023; Matalinares et al., 2016; Melo et al., 2021; Morales & Pérez, 2019; Naser et al., 2022; Pintrich, 2004; Pozar, 2002; Samaniego & Buenahora, 2016; Sanagavarapu et al., 2019; Santander et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2023; Tholen et al., 2022; Trigueros et al., 2020; Weinstein et al., 2002; Ya et al., 2024; Zandvliet et al., 2019). (2) Effort, defined as the levels of perseverance, constancy, regular study habits, the capacity to delay reward, control of the time and situation for studying, and internal attribution of academic performance (Mondragón et al., 2017; Muñoz, 2022; Weinstein et al., 2002). (3) Autonomy, defined as the extent to which the student employs self-regulation learning (active process to choose learning goals, and to control and regulate cognitive processes, motivation and behaviour), the active search for information sources, the integration of information from different sources, the generation of own theories, and the active search of empirical evidence of the theories and the applications of new knowledge (Al Mulhim, 2021; Allgood et al., 2000; Alonso et al., 2007; Beltrán et al., 2006; Jiménez et al., 2018; Kolb & Koln, 2005; Lilia et al., 2021; Maya et al., 2021; Merino-Soto et al., 2022; Pérez et al., 2011; Pintrich, 2004; Said et al., 2010). (1) Understanding and Career Interest, understood as the levels to which the student focusses on deep learning, studying to attain a profound comprehension of the concepts and their interrelationships, and closely related to the interest in focusing learning on the knowledge and skills required for the chosen profession (Alonso et al., 2007; Álvarez & Fernández, 2005; Han et al., 2024; Herrera & Rodríguez, 2011; Jiménez et al., 2018; Kolb & Koln, 2005; Leite et al., 2010; Mondragón et al., 2017; Weinstein et al., 2002). (5) Social and Physical Context, refers to the preferences to study alone vs. with other students, and preferences about the study place (Acevedo et al., 2009; Álvarez & Fernández, 2005; Mondragón et al., 2017; Park et al.2021; Yang & Kang, 2020). The present study aims to obtain evidence of validity for a scale that measures the Diversity in Learning (DinL) construct. The validity evidence includes four key aspects: (1) internal structure, expecting to confirm a five-dimension model, (2) invariance across male and female participants, (3) concurrent validity with academic performance, and (4) internal consistency of the dimensions. The scale measures this construct individually, understood at individual level as the combination of main dimensions comprising the psychological processes, styles, habits, difficulties, internal and external resources, contextual and psychosocial factors defining the individual learning profile that distinguish it from other individual profiles within a diversity in learning in the academic classroom. It is hypothesized that the DinL scale will show optimal evidence of validity and reliability. Likewise, the five-dimensional structure of the scale defining the DinL integrative construct will show adequate internal consistency qualities, expecting this structure and measurement properties to hold across men and women. Participants Using a cross-sectional design, the initial sample was composed of 1,841 students enrolled at the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM) in Spain; 11% of cases were excluded from the study due to major errors in responses or incomplete questionnaires. The final sample was 1,644 students with a mean age of 24.37 (SD = 8.73), 1,167 (70.9%) of whom were women, 1,285 (78.2%) were undergraduate, 233 (14.2%) were studying at master’s level, and 126 (7.6%) were PhD students from different disciplines (social science, science, humanities and engineering); 1,331 of the students were born in Spain and other European countries (85.1%) and the rest were from South America (9.2%), Asia (2.3%), North America (2.1%), and Africa (1.3%). The sample size was determined by the recommendation that a sufficient sample for analysis with WLSMV estimator must be made up of more than 200-500 participants (Kyriazos, 2018). (See Table 3 for the sampling procedure). Instruments The Diversity in Learning Scale (DinL) is an individually self-administered scale that describes the psychosocial diversity of learning patterns observed in the classroom. It comprises of 28 items and represents the above-defined dimensions in 5 sub-scales: Coping with Difficulties, Effort, Autonomy, Understanding and Career Interest, and Social/Physical Context. The items were rated on a four-point Likert scale from 1,= nothing or very little, 2 = some, 3 = quite a lot, 4 = a lot (see Table 4 for a list of the items grouped in each of the sub-scale). The scale was constructed in three stages: (1) an extensive bibliographic research of the fundamental psychosocial and psycho-educational dimensions regarding learning styles, habits, strategies and difficulties; (2) a theoretical and empirical development of the DinL construct, including its constituent dimensions; and (3) a survey conducted with a large sample of university students for the purpose of scale validation. Academic performance was measured by an item that asked for the average grade obtained in the previous academic year. Procedure Participation in the study was voluntary, and all participants provided informed consent before completing the questionnaire. Data collection adhered to the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013) and was conducted in compliance with national and European data protection regulations, ensuring anonymity and confidentiality. In addition to the approval of the Research Ethical Committee at the University of Madrid (Ref. No CE_20211118-15_SOC), the study was guided by principles of ethical and scientific rigor. These included:

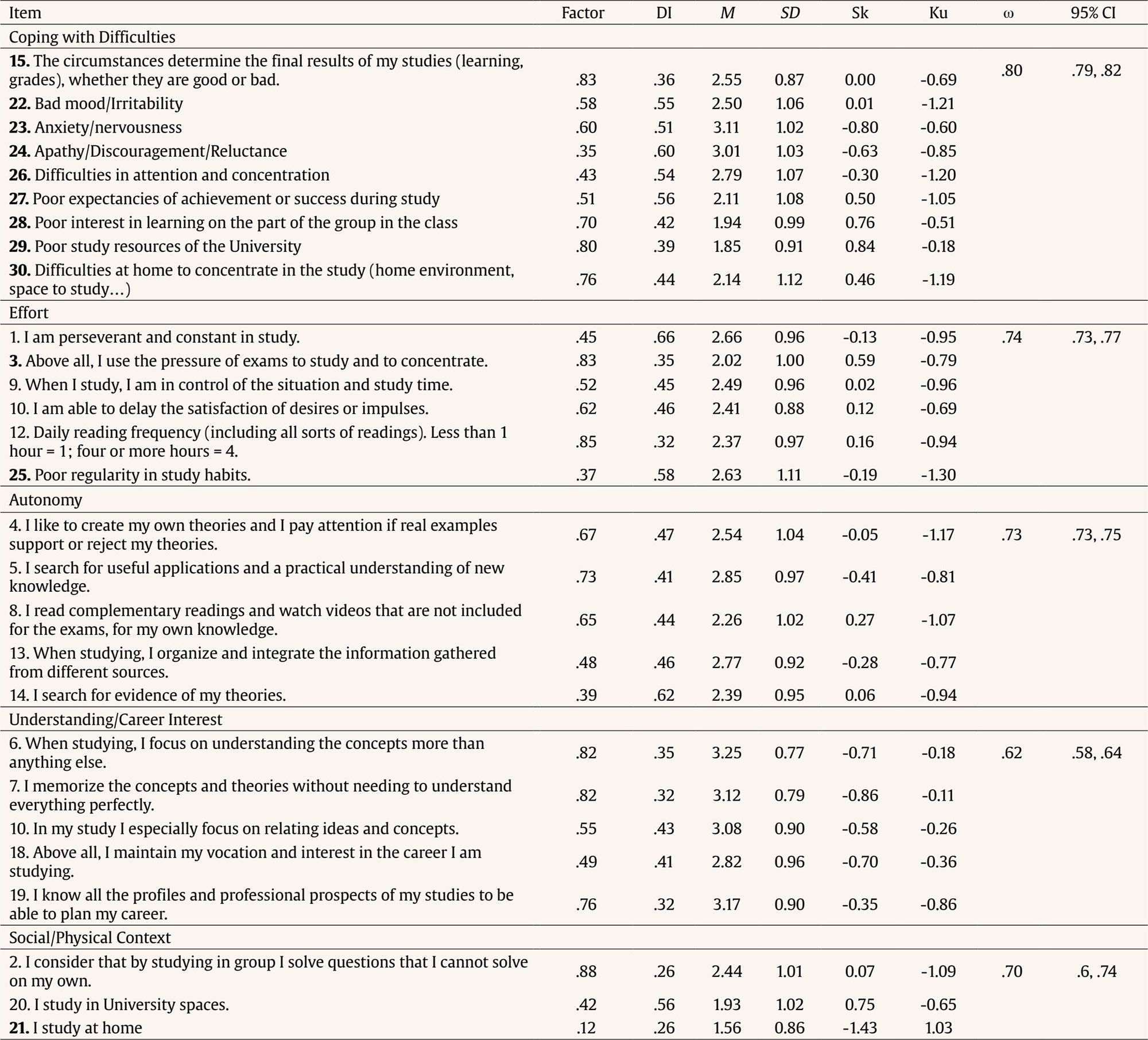

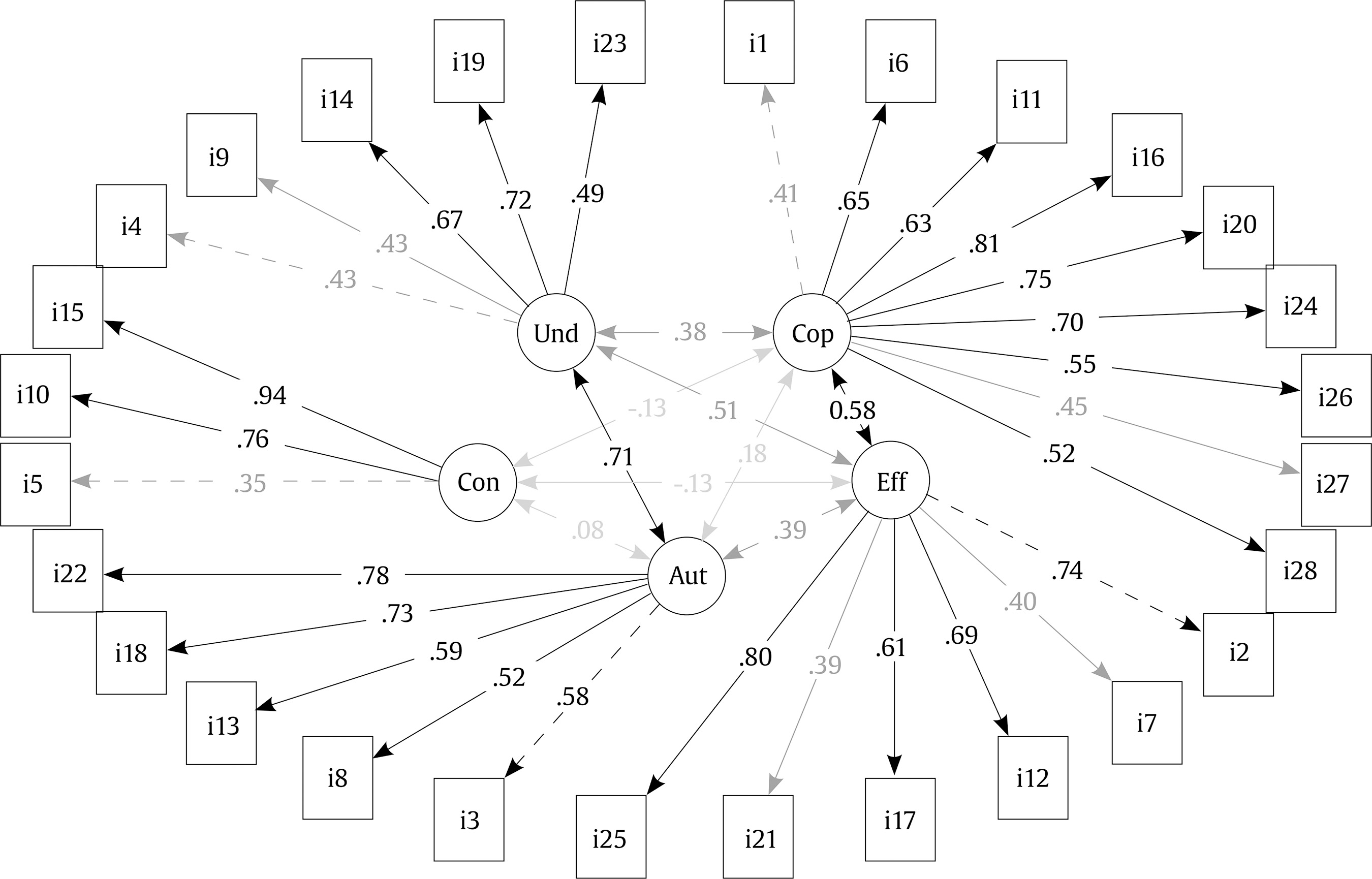

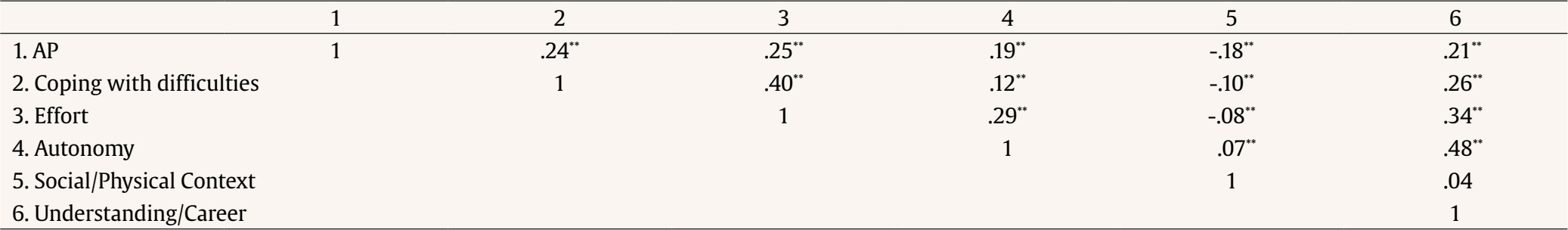

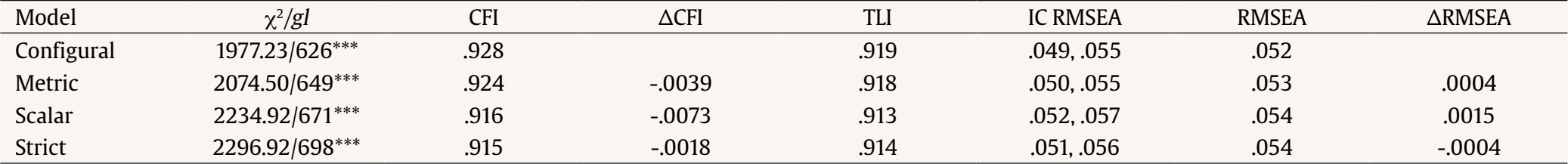

Data Analysis Data analyses were performed using the statistics program R (RStudio, 4.2.2) to address the research objectives. First, descriptive analyses were conducted to characterize the sample. To evaluate the internal structure of the DinL scale, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to test the hypothesized five-factor model. Given the categorical nature of the data, analyses were performed using the weighted least squares means and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator, which is robust to violations of multivariate normality (DiStefano & Morgan, 2014). The polychoric correlation matrix served as the basis for the analysis. The scale was assessed using the goodness of fit indexes: comparative fix index > .90 (CFI; Bentler, 1990) and the Tucker Lewis index > .90 (TLI; Tucker & Lewis, 1973), the root mean square error of approximation < .80 (RMSEA; Steiger, 1990) and the standardized root mean residual < .80 (SRMR; Fan & Sivo, 2007). To investigate invariance across sexes, a multigroup confirmatory factor analysis was performed, comparing nested models of configural, metric, scalar, and strict invariance. The fit was evaluated using χ2, CFI, TLI, and RMSEA. Differences between the models were examined with a ΔCFI test and a ΔRMSEA test, each considering the less restrictive model. A non-optimal result in ΔCFI is less than -.01 and .015 in ΔRMSEA (Chen, 2007; Dimitrov, 2010). Internal consistencies of each of the five subscales of the DinL scale were assessed as reflected by the omega McDonald coefficient (ω) and confidence intervals (Viladrich et al., 2017). The score ≥ .70 is considered “acceptable”, ≥ .80 “good” and ≥ .90 “excellent” indicators (Taber, 2018). The model parameters were estimated under the same conditions as in the confirmatory factor analysis, using the polychoric correlation matrix and the WLSMV estimation method. Finally, the concurrent validity was evaluated through Pearson correlation coefficients using the five scales of DinL and perceived academic performance. Descriptive Statistics Table 4 provides the means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis of the 28 items. The skewness and kurtosis values are below ± 1.96, indicating that the items conform to a normal distribution (Mardia, 1970; West et al., 1995). Additionally, the discrimination indices (DI) demonstrate that the items effectively differentiate between participants with varying levels of the measured constructs. Table 4 Psychometric Properties of Items and Reliability of Subscales   Note. DI = discrimination index; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; Sk = skewness; Ku = kurtosis. Item numbers in bold are the inverse items. Confirmatory Factor Analyses The tested measurement of the goodness-of-fit showed CFI = .932, TLI = .925, RMSEA = .065 [.063, .068] and SRMR = .067 for the five subscales of the model. The model fit values were adequate for the threshold proposed. The reliability of the scales in terms of internal consistency score between ω = .62 to .80, with an acceptable but lower score for the subscale Understanding/Career Interest (Table 4). Figure 1 shows the path diagram of the model with the standardized weights. Figure 1 Path Diagram of the Model with the Standardized Weights.   Note. Con = social/physical context; Cop = coping with difficulties; Und = understanding/career interest; Eff = effort; Aut = autonomy. Measurement Invariance The measurement invariance of the DinL scale was assessed to examine its applicability across male and female subgroups. Table 5 summarizes the fit indices for the configural, metric, scalar, and strict invariance models. The results indicated adequate fit for the configural, metric, and scalar models, demonstrating that the scale retains the same factor structure and metric properties across subgroups. However, the strict invariance model showed a slight decrease in fit indices (ΔCFI = -.0018), suggesting minor variations in item residuals between groups. Despite this, the results confirm that the scale is robust for comparing latent constructs across genders at the configural, metric, and scalar levels, supporting its use for examining gender-based differences in the DinL construct. Concurrent Validity The five DinL subscales were correlated with perceived academic performance. Table 6 indicates that all the subscales were statistically significant at the .01 level. The perceived academic performance showed a positive relationship with Coping with Difficulties, Effort, Autonomy and Understanding/Career Interest, but a negative one with Social/Physical Context. Table 6 Pearson Correlation Coefficient between the Five Subscale and Academic Performance   Note. AP = academic performance. *p < .05, **p < .01. This paper is the result of a research line that built an integrative concept of DinL in a step-by-step process of integrating bibliographic, quantitative, qualitative, and participatory analyses, with a large participation on the part of students and professors. A main aim of the present study was to analyse and operationalize the learning dimensions that define the integrative DinL construct and the internal and external validity of a scale measuring such dimensions. The results in this study support an optimal validity of the 5 major subscales defining DinL. The subscales measuring the learning dimensions are consistent with the main research literature pointed out above (e.g., Al Mulhim, 2021; Bernard et al., 2024; Dumitrescu & De Caluwé, 2024; Heritage et al., 2023; Jiménez et al., 2018; Martos et al., 2023; Maya et al., 2021; Park et al.,2021; Weinstein et al., 2002). The results show internal validity qualities regarding construct, contents, and the consistency values of the scale. The omega internal consistency coefficients report an adequate reliability of the DinL factors, except for Understanding and Career Interest. The lower omega in this factor may be attributable to its measurement of the dimension with the largest content, which encompasses related items concerning studying by understanding and focused on the professional career. This factor necessitated a more extensive array of contents within the group of items comprising it. Regarding the analyses of items, the values show acceptable discrimination indices (Ebel, 1965). Besides, the responses are distributed between adequate values (0.70-1.11). Also, the asymmetry and kurtosis results (-1.5-1.5) meet the multivariate normality assumption (Forero et al., 2009). Despite some small shortfalls in strict invariance, the results in configural, metric, and scalar variance showed good results, indicating that the structure proposed is similar in both groups, the weights are also similar (i.e., the factors have the same contents in men and women), and the group mean differences in the items and factors are equal in both groups. However, the uniqueness parameters are not equal, which implies differences in measurement precision. The latter is not essential for comparison (Abad et al., 2011). Finally, concurrent validity showed highly significant relationships between all the DinL factors and academic performance as a criterion. Positive relationships were found between perceived performance and the Coping with Difficulties, Effort, Autonomy, and Understanding/Career Interest factors. The relationships were inverse with Social/Physical Context. It is worth noting the large positive relationship between all the learning dimensions and academic performance (taking the individual pole of the Social/Physical Context as positive). A number of studies have identified specific learning styles and strategies linked to academic performance and achievement, whereas other studies have not found such relationships (e.g., Batool, 2020; Bully, 2019; Herrera et al., 2020; Lardy et al., 2022; MacCann et al., 2020; Maya et al., 2021; Moral-García et al., 2020). The DinL scale showed a high predictive power on academic performance in all its dimensions. This indicates that no specific dimension of the integrative DinL construct is clearly superior in predicting academic outcomes when compared to the others. It may depend on the combination (or profile) of dimensions of each student, or on the field of study. It is important to point out that this study did not focus on learning abilities or skills but on the diversity of learning styles, strategies, habits and difficulties. Nevertheless, different learning and study patterns may be partly related to cognitive skills regarding academic achievement. Students may choose to use certain learning styles because they are more skilled at them, or simply because they were taught to study that way, or because it is more effective in the academic achievement model their school uses, regardless of their abilities. The relationship between DinL and cognitive abilities and their weight on learning performance and academic achievement deserve further studies. Another interesting result is related to the similarities between males and females in the structure of learning dimensions. This study shows that there are no basic differences in the structure of the 5 dimensions defining DinL between sexes. Another different issue is whether there are differences in the levels of each dimension between males and females, which requires further study. In general, results show a DinL scale comprising a sound and robust combination of five dimensions, gathering an overarching measurement of the learning process. The discriminatory features of the scale allows the measurement of DinL levels and qualities in a classroom. Also, the integrated DinL concept that links the learning dimensions with psychosocial and contextual characteristics facilitates pinpointing and addressing those external factors that may affect the types of styles, habits, strategies, psychosocial difficulties and academic performance of student groups in the classroom. Conclusions This study has examined the concept of diversity in students’ study and learning processes, utilizing a holistic definition of the Diversity in Learning (DinL) construct. This definition encompasses not only behavioral and psycho-educational aspects but also contextual and psychosocial factors that influence learning. The findings underscore the relevance and potential of an integrative approach to understanding the increasing DinL in university classrooms. DinL extends beyond established fields of research such as learning styles and strategies, which have shown limited applicability in addressing the complexity and diversity of higher education environments. Additionally, this study demonstrates the feasibility of operationalizing DinL using a concise scale that evaluates five meaningful dimensions, characterized by robust psychometric properties. This scale holds significant potential for research and practical application, enabling a more personalized, equitable, and inclusive approach to higher education. Such an approach may enhance academic performance and success, particularly for students who do not conform to the predominant learning patterns within their respective academic fields. Applications The present study validates the soundness and robustness of an innovative and integrative DinL framework within the university context. The developed scale offers practical applications for educators, allowing the categorization of students into DinL profiles based on their unique combinations of learning dimensions. This categorization could facilitate the alignment of teaching strategies with the diverse learning needs of students, moving away from the traditional “one-size-fits-all” approach (Khalil et al., 2020) that persists in many academic contexts. This tool may be particularly beneficial in designing targeted strategies for groups of students whose learning patterns deviate significantly from the norm, thereby fostering inclusivity and equity. Additionally, it supports the organization of DinL-based student groups to enhance collaborative learning outcomes. Such an approach repositions DinL from being perceived as a challenge to being viewed as a resource for promoting learning and improving academic performance. Furthermore, the scale provides insights into the psychological and social factors influencing these learning dimensions, enabling interventions to enhance learning experiences. Limitations and Future Studies This study acknowledges certain limitations, including lower omega reliability in one subscale and minor shortcomings in strict invariance. Regarding future studies, the analysis of the influence of digital technologies on learning patterns is set to be of fundamental importance. The present research project did not find significant evidence to suggest that the available digital tools have fundamentally altered students’ learning methods, strategies, or habits to date. Research in this area, including that of Zambrano et al. (2018), supports this observation, indicating that digital tools currently function primarily as supplementary aids rather than transformative influences on established learning patterns. Nevertheless, future studies should explore the potential impact of emerging digital learning methodologies on the development of diverse learning strategies. Finally, while this study was conducted at a large public university in Spain with substantial psychosocial diversity, the scale is currently being tested in universities across different countries to evaluate its psychometric properties in varied social contexts. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Acknowledgements We are especially grateful to Zeri Ryerson and Dawn Ramey for their review of the English version. We would also like to thank Javier Ramón, Rodrigo Borja and all the students and professors who participated in helping gather the sample. Cite this article as: Gandarillas, M. A., Elvira-Zorzo, M. N., Osa-Subtil, I., Rodríguez-Vera, M., & Chacón-Fuertes, F. (2025). The measurement of the diversity in learning to enhance educational inclusion and achievement. Validation of a scale in higher education. Psicología Educativa, 31(2), 111-120. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2025a14 References |

Cite this article as: Gandarillas, M. A., Elvira-Zorzo, M. N., Osa-Subtil, I., Rodríguez-Vera, M., and Chacón-Fuertes, F. (2025). The Measurement of the Diversity in Learning to Enhance Educational Inclusion and Achievement. Validation of a Scale in Higher Education. PsicologĂa Educativa, 31(2), 111 - 120. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2025a14

Correspondence: mgandari@ucm.es (M. Á. Gandarillas).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS