Social Support and WomenŌĆÖs Smoking during the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review

[El apoyo social y el consumo de tabaco de las mujeres durante el periodo perinatal: una revisi├│n sistem├Ītica]

Cristina M. Posse, Alba Val, and M. Carmen Míguez

Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/clh2025a4

Received 15 March 2024, Accepted 21 November 2024

Abstract

Background: This review focuses on analyzing the relationship between social support and women’s smoking during the perinatal period. Method: A literature search was conducted in PsycINFO, Medline, and SCOPUS covering the period between January 2010 and August 2024. Fifteen studies meeting the inclusion criteria were selected. Results: A total of 10 studies examined the relationships between social support and smoking during the perinatal period and 5 studies examined the influence of partner smoking during this period. Lack of social and partner support, an environment of smoking friends, and not having a partner were associated with continued smoking during pregnancy. Having a smoking partner was also associated with continued smoking during pregnancy or relapse postpartum. Conclusions: The absence of social support and having a partner who smokes were found to be related to women’s tobacco consumption during the perinatal period.

Resumen

Introducción: Esta revisión se centra en el análisis de la relación entre el apoyo social y el consumo de tabaco por parte de las mujeres durante el periodo perinatal. Método: Se realizó una búsqueda bibliográfica en PsycINFO, Medline y SCOPUS desde enero de 2010 a agosto de 2024. Se seleccionaron 15 estudios que cumplían los criterios de inclusión. Resultados: Un total de 10 estudios examinaban las relaciones entre el apoyo social y el tabaquismo durante el periodo perinatal y 5 la influencia del tabaquismo de la pareja durante este periodo. La falta de apoyo social y de la pareja, un entorno de amigos fumadores y no tener pareja se asociaban con seguir fumando durante el embarazo. Tener una pareja fumadora también se asociaba con seguir fumando durante el embarazo o recaer después del parto. Conclusiones: Se observó que la ausencia de apoyo social y tener pareja fumadora se relacionaban con el consumo de tabaco de la mujer durante la etapa perinatal.

Palabras clave

Consumo de tabaco, Apoyo social, Embarazo, Postparto, PerinatalKeywords

Smoking, Social support, Pregnancy, Postpartum, PerinatalCite this article as: Posse, C. M., Val, A., and Míguez, M. C. (2025). Social Support and WomenŌĆÖs Smoking during the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review. Clinical and Health, 36(1), 25 - 35. https://doi.org/10.5093/clh2025a4

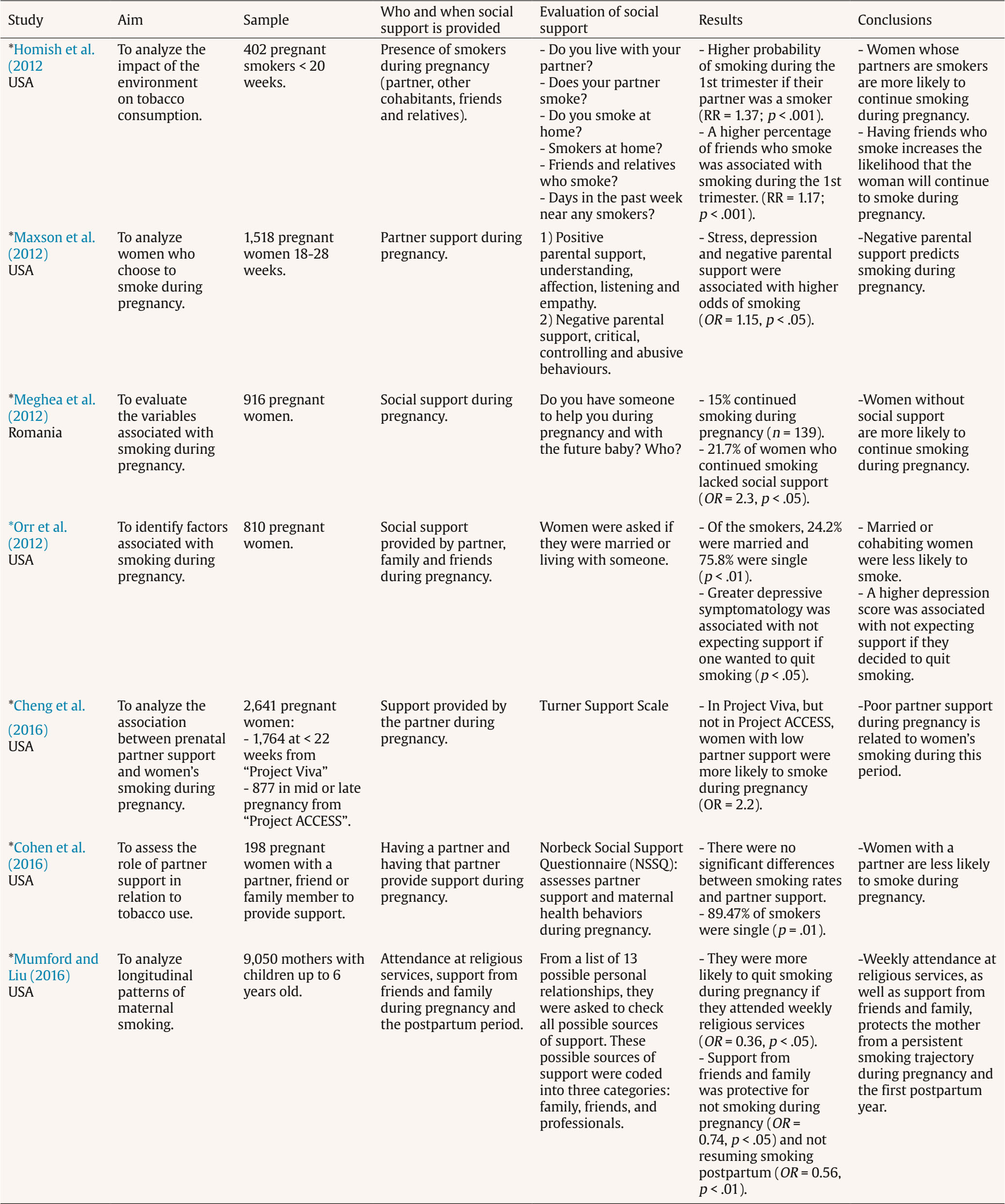

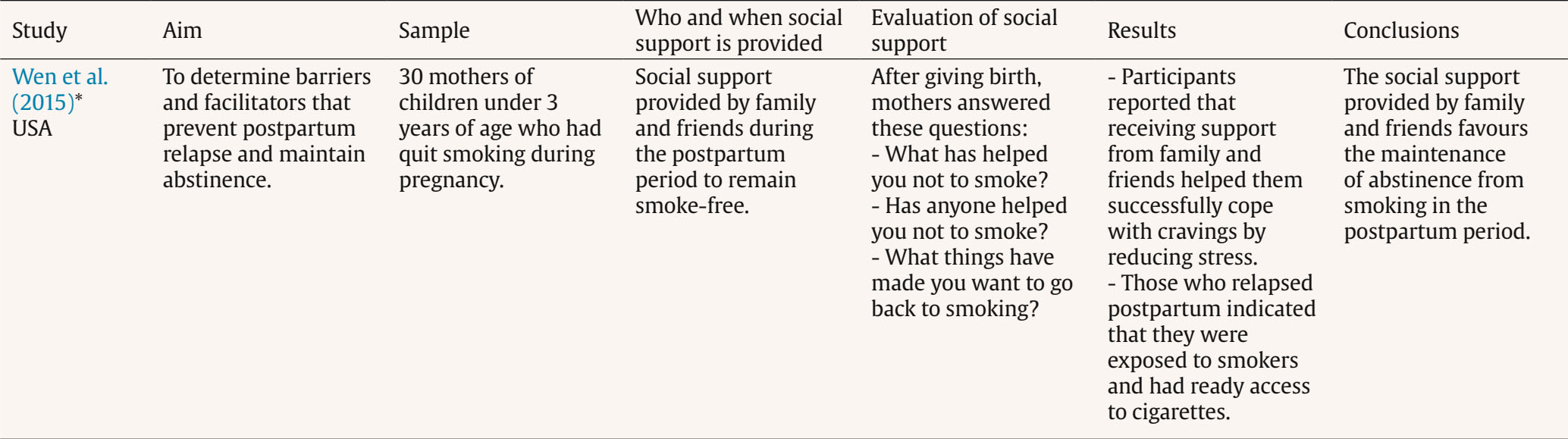

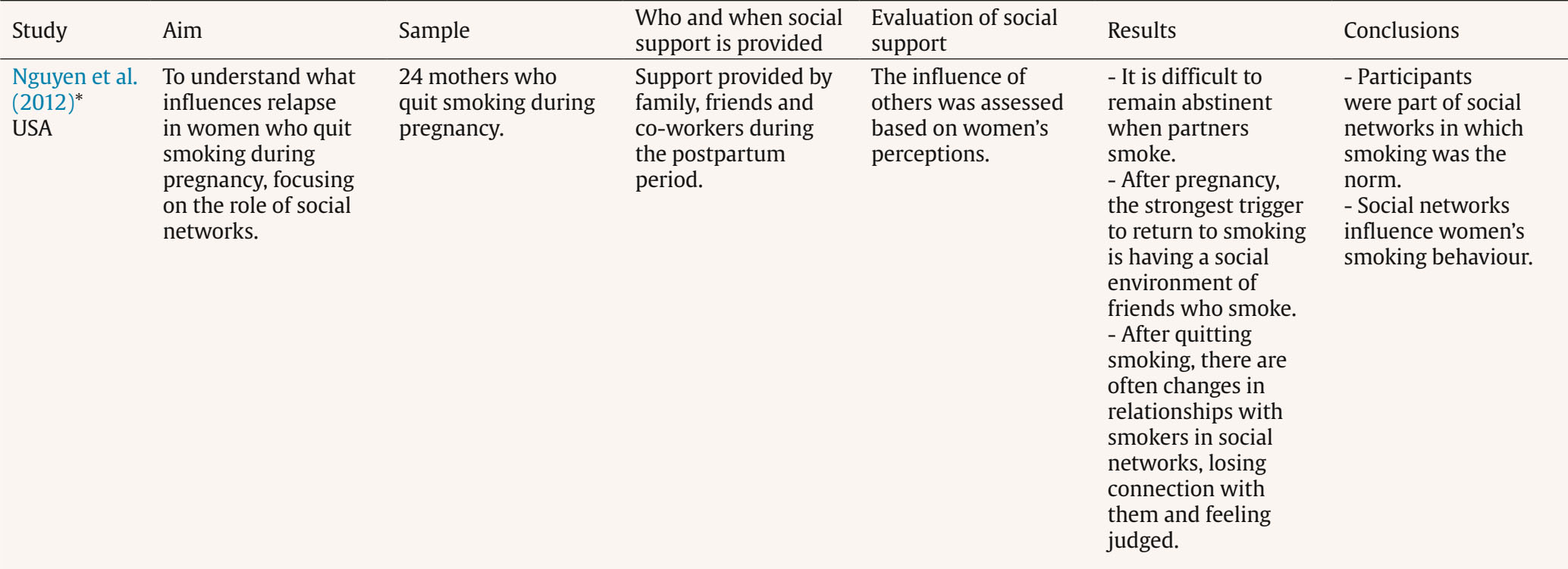

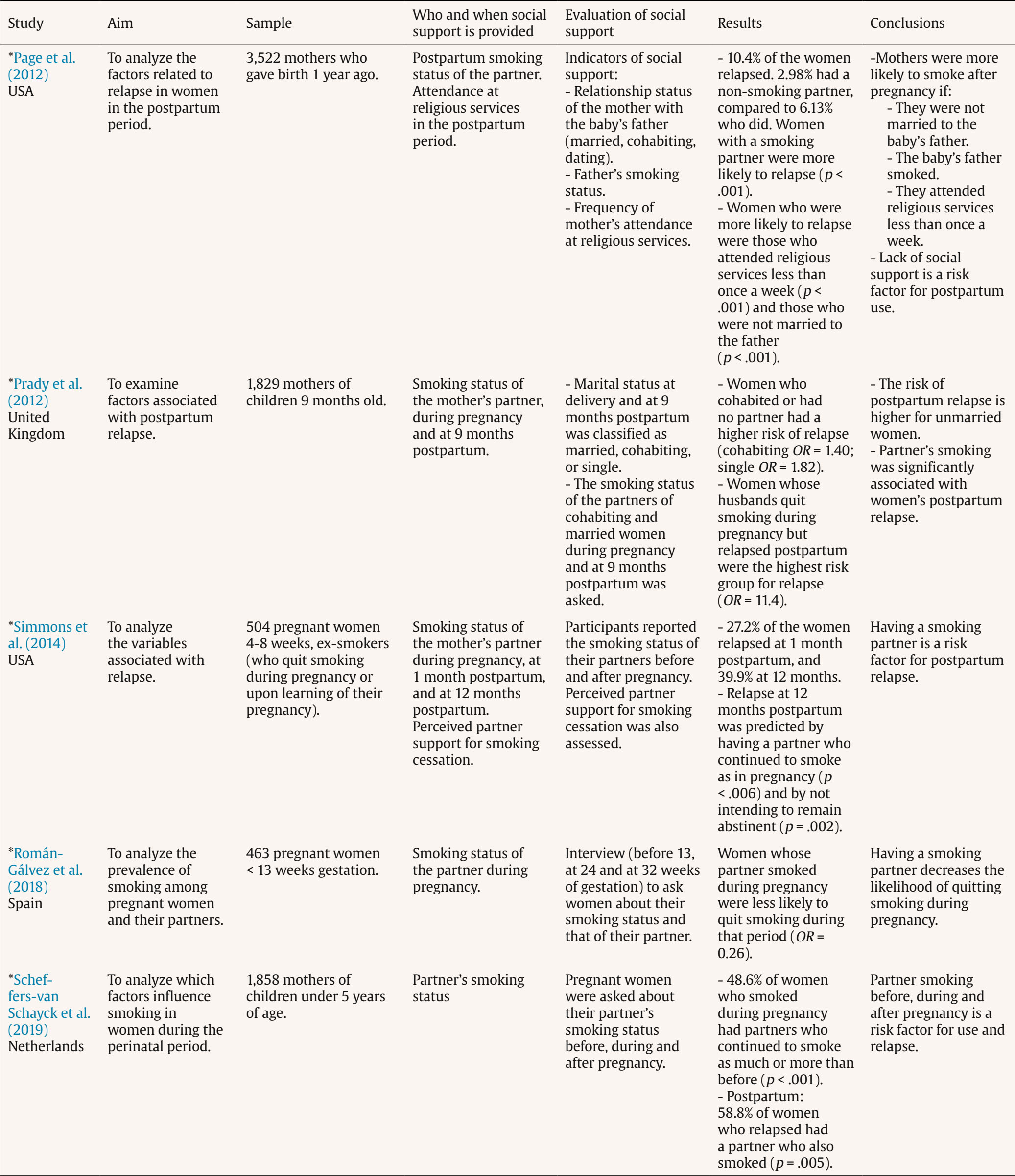

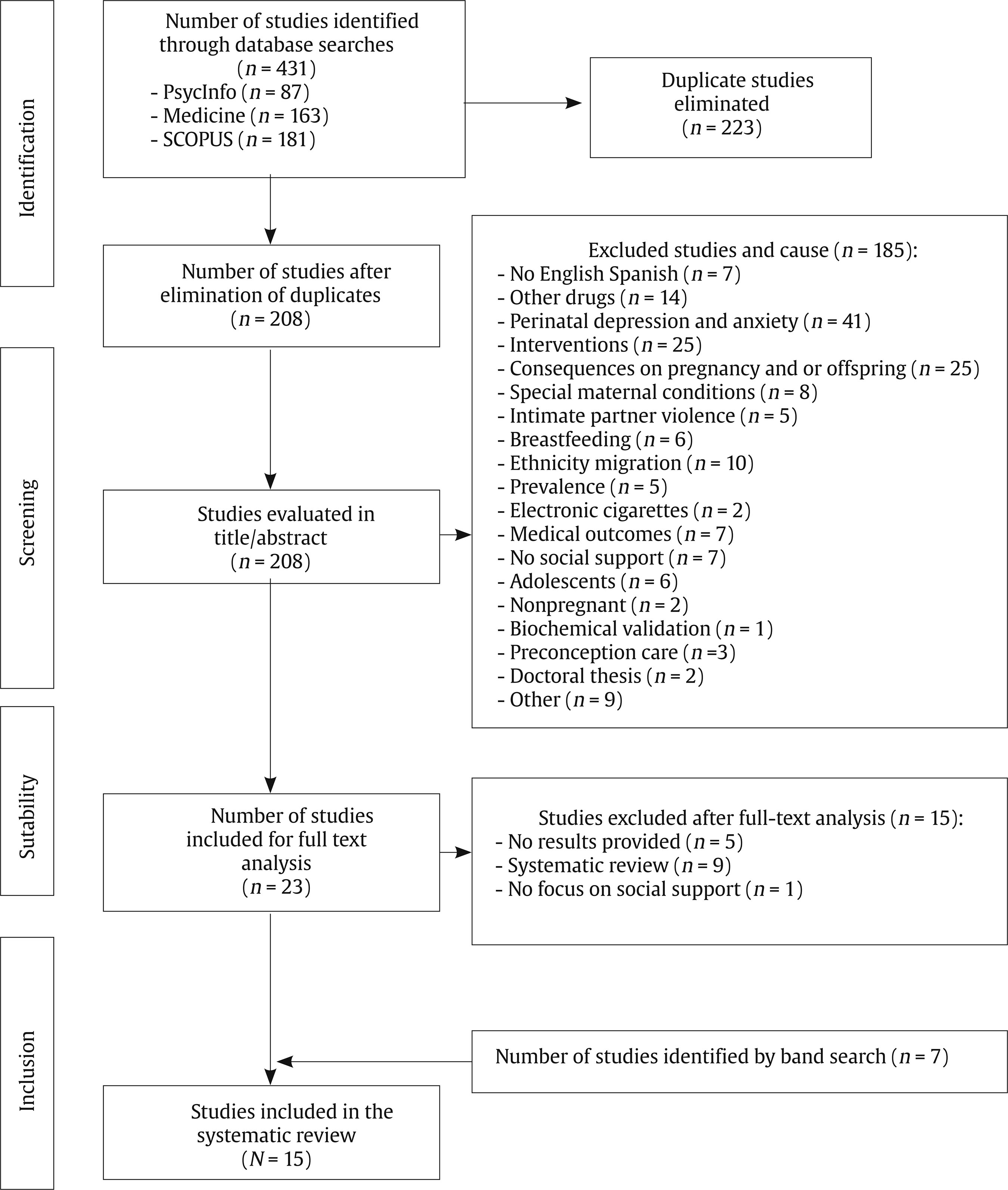

Correspondence: mcarmen.miguez@usc.es (M.C. Míguez).Smoking affects many women during pregnancy. In Spain, tobacco consumption in pregnant women is reported to range from 15.5% to 30.3% (Míguez et al., 2017; Rojas et al., 2022; Santiago-Pérez et al., 2019). In the postpartum period, women who have smoked throughout pregnancy are joined by those who relapse after quitting during pregnancy. Therefore, the prevalence of smoking is usually higher in the postpartum period than during pregnancy. Relapse rates have been reported to range from 15.2% at 2 months postpartum (Míguez & Pereira, 2021a), to 36% and 42.6% at 6 and 9 months postpartum (C. L. Lin et al., 2019; Schilling et al., 2018), reaching 78% at 1 year postpartum (Patten et al., 2019). Women who continue to smoke during pregnancy are exposed to some specific consequences of smoking, not only for themselves, but also for their offsprings. The mother is at increased risk of cardiovascular and pulmonary events and of developing preeclampsia (Roelands et al., 2009; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS, 2014]). In terms of gestational complications, there is an increased risk of ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, premature delivery, placental abruption, reduced gestation, and low birth weight (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA, 2020]; USDHHS, 2014). Likewise, neonates may be born with congenital malformations or neonatal abstinence syndrome, and there is also an increased risk of sudden infant death (NIDA, 2020; USDHHS, 2014). A number of factors associated with tobacco consumption during pregnancy have been identified (Míguez & Pereira, 2016). Most notably, these factors include having a low educational and socioeconomic status and living with smokers or having a partner who smokes (El-Khoury et al., 2017; Gilbert et al., 2015). By contrast, higher educational and economic status, having non-smoking cohabitants, primiparity, and planned breastfeeding are factors associated with smoking cessation in this period (Schneider et al., 2010). Regarding the postpartum period, studies that have analyzed factors associated with smoking relapse highlight being a mother at a younger age, having a lower educational level, living with smokers, and exposure to smoky environments (Logan et al., 2017; Schilling et al., 2018). However, several protective factors have also been found to prevent relapse and are therefore associated with maintaining abstinence during this period. These factors include having a partner who does not smoke, having direct support from a significant person, and being pregnant for the first time (Logan et al., 2017). Psychosocial Variables Related to Smoking in the Perinatal Period: The Role of Social Support Of the psychological variables related to smoking in the perinatal period, the most commonly studied are depression and anxiety (De Wilde et al., 2013; Goodwin et al., 2017), both of which are important predictors of smoking during pregnancy and the postpartum period. However, social support, a variable which has also been associated with smoking in pregnant women (Miyazaki et al., 2015), has scarcely been studied. Social support has been defined in multiple ways. For example, Lin et al. (1979) defined social support as “instrumental or expressive provisions, real or perceived, provided by the community, social networks, and close friends.” Numerous benefits, both physical and psychological, are attributed to having good social support. In the case of perinatal mental health, receiving support during this period can help to prevent depression and reduce its effect (Huang et al., 2020; Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., 2023). By contrast, pregnant women with low levels of social and partner support have been found to have higher levels of depression and to be more affected by stress (Cheng et al., 2016; Li et al., 2021). Taking social support into account as an important factor in health, and consequences of smoking on the mother and her offspring and its high prevalence, it is important to examine how it acts and how it affects to the smoking behaviour of women in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Although social support is known to be an important component of smoking cessation during pregnancy (Greaves et al., 2011), few studies have analyzed the role played by this factor in smoking at this period. Therefore, the general purpose of the present review was to analyze the influence of social support on smoking during the perinatal period. Social support will be understood as the presence of any help, physical or psychological, from significant people (family, partner, friends), with the aim of helping mothers to quit smoking or with any other problem in their lives related, or not, to the care of the newborn. The specific objectives of the study were to determine (1) the role of social support in tobacco consumption or smoking cessation during pregnancy, (2) the role of social support in maintaining abstinence from smoking or relapse during the postpartum period, and (3) the influence of the smoking status of partners on the tobacco consumption of pregnant women. The study selection process was carried out following the recommendations of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). Inclusion Criteria In order to be selected, the studies had to: 1) be published in scientific journals, 2) be quantitative or qualitative, 3) analyse the social support variable in relation to women’s smoking in the perinatal period, 4) consider the support of friends, family, or partner, 5) be in Spanish or English between 2010-2024, 6) be carried out with pregnant or postpartum women 18 years old or older, smokers or ex-smokers, and 7) come from any country. Search Strategy A literature search was carried out in the PsycINFO, Medline, and SCOPUS databases to identify papers published between January 1st 2010 and August 31st 2024. The following keywords were used in the initial search by combining them as follows: “social support” OR “partner support” OR “perceived support” OR “interpersonal support” (abstract/title) AND “smok*” OR “tobacco” (abstract/title) AND “pregnan*” OR “antenatal” OR “prenatal” OR “antepartum” OR “postnatal” OR “postpartum” OR “perinatal” (abstract/title). Strategy for the Selection of Studies and Analysis of Results The selection of articles was carried out independently by two researchers and, in case of discrepancies, discussed between them. First, all publications found within the search criteria were transferred to Refworks and all repeated publications were removed. Subsequently, the studies were selected by reading first the titles and abstracts and, finally, the full text. The full article selection process is summarized in Figure 1. In order to provide a better understanding of the results, the studies were divided into two categories. First, studies that looked at the relationship between social support and smoking during the perinatal period. These studies were further divided into four subcategories depending on whether they looked at the relationship between use or cessation during pregnancy, or maintenance of abstinence or relapse during the postpartum period. On the other hand, the second category grouped studies that looked at partner smoking during the perinatal period. The extracted data were synthesised by year, objective, sample, measures, results, and conclusions. Statistical data from the studies were evaluated. Study Selection A total of 431 potential scientific publications resulted from the designed search strategy: PsycINFO (n = 87), Medline (n = 163), and SCOPUS (n = 181). Of these, 223 were duplicated, so the final number of publications after eliminating duplicates was 208. A systematic search was then carried out, in which the retrieved studies were screened. A series of inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to guide the selection process. After reading the title and abstract of the studies, a total of 185 studies were excluded because they concerned other drugs, focused on the mental health of the mother or the consequences of tobacco use in pregnancy, analyzed the prevalence of consumption, analyzed the efficacy of smoking cessation interventions, or did not focus on social support, among other reasons. After screening, the full text of each the 23 articles selected was analyzed, and finally a total of eight studies were included; the other 15 were excluded because they did not provide results (n = 5), did not focusing on the social support variable (n = 1) or because they were systematic reviews (n = 9). A further seven studies identified by a manual search were added. Therefore, 15 articles were finally included in this review. All the selected studies met the quality criteria evaluated using the Mixed Methods Assessment Tool (MMAT; Hong et al., 2018), through two general screening questions and five specific questions depending on the design of each study. All pre-screened studies were considered eligible and of good quality. The authors then read each article in full text, extracting the information of interest for the review. Once the results were selected, they were compiled in table format. Characteristics of Selected Studies The 15 studies reviewed are observational studies and most of them used a quantitative methodology. Only two (Nguyen et al., 2012; Wen et al., 2015) are qualitative. Most of the studies (n = 12) were conducted in the USA. The remaining three were conducted in Romania (Meghea et al., 2012), Spain (Román-Galvéz et al., 2018), and the Netherlands (Scheffers-van Schayck et al., 2019). Of the 15 studies, nine evaluated pregnant women, at different points in pregnancy, smokers or non-smokers (Cheng et al., 2016; Cohen et al., 2016; Dascăl et al., 2020; Homish et al., 2012; Maxson et al., 2012; Meghea et al., 2012; Orr et al., 2012; Román-Gálvez et al., 2018; Simmons et al., 2014), while six studies assessed women who were already mothers (Mumford & Liu, 2016; Nguyen et al., 2012; Page et al., 2012; Prady et al., 2012; Scheffers-van Schayck et al., 2019; Wen et al., 2015). To assess social support, some studies assessed support provided by partners, family or friends (Cheng et al., 2016; Dascăl et al., 2020; Maxson et al., 2012; Meghea et al., 2012; Mumford & Liu, 2016; Nguyen et al., 2012; Wen et al., 2015), other studies assessed whether women had a partner (Cohen et al., 2016; Orr et al., 2012), other studies assessed whether women were surrounded by smokers (Homish et al., 2012), and other studies assessed whether or not the partner was a smoker during the perinatal period (Page et al., 2012; Prady et al., 2012; Román-Galvéz et al., 2018; Scheffers-van Schayck et al., 2019; Simmons et al., 2014). After analyzing the 15 studies selected, we found that 10 analyzed the relationship between social support and smoking, and five analyzed the influence on the pregnant women’s smoking behavior of having a partner who smoked. The main findings are discussed below. Relationship between Social Support and Smoking in the Perinatal Period This section includes the 10 studies that analyzed the relationship between social support and women’s smoking in the perinatal period, considering consumption and relapse after a period of abstinence from smoking and also cessation and maintenance of abstinence. Two of these studies are qualitative (Nguyen et al., 2012; Wen et al., 2015). Social Support and Smoking The relationship between social support and smoking in women in the perinatal period was analyzed in seven studies, six of them being conducted in the USA (see Table 1). The first study identified was Homish et al.’s (2012), which studied the impact of socio-environmental influences on smoking during the first trimester of pregnancy in 402 US women who were smokers. The non-presence of smokers during pregnancy (partner, other cohabitants, friends, and relatives) was considered a measure of social support. It was found that women were more likely to smoke during the first trimester of pregnancy if their partner was a smoker (p < .001), with the risk of smoking increasing by 37%. However, the presence of other cohabitating smokers was not associated with an increased risk of smoking. On the other hand, women with a greater number of friends (not family members) who smoked, and were therefore more frequently exposed to environmental tobacco, were also more likely to smoke during the first trimester (RR = 1.17, p < .001). Table 1 Social Support and Tobacco Consumption in Women during Pregnancy   Note. RR = risk factor; OR = odds ratio. *Statistically significant difference. Another study reviewed was Maxson et al.’s (2012), which analyzed the profiles of women who continued to smoke during pregnancy. They selected 1,518 women at 18-28 weeks of gestation, of whom 1,036 were non-smokers, 215 quit upon learning of the pregnancy, and 267 continued to smoke. One of the variables considered in the analysis was the support provided by the partner during pregnancy (partner support), analyzing the amount of support and the existing conflict in the relationship. Two components of paternal support were measured: positive paternal support, composed of understanding, affection, listening and empathy, and negative paternal support, composed of critical, controlling and abusive behaviour. Negative partner support was found to be associated with higher odds of being a smoker during pregnancy (OR = 1.15, p < .05). The study by Meghea et al. (2012), the only non-US study, assessed smoking prevalence and smoking-associated variables in 916 pregnant women in Romania, under the assumption that lack of social support would become a risk factor for smoking during this period. To assess social support during pregnancy, women were asked whether they had someone to help them during this period and after birth of the baby. Fifteen percent of the women continued to smoke during pregnancy, compared with 26% who stopped smoking when they found out about their pregnancy. The 21.7% of women who continued to smoke reported that they lacked social support. Women without social support were more likely to continue smoking (OR = 2.3, p < .05). Another study carried out in USA (Orr et al., 2012) aimed to identify the factors associated with increased risk of smoking during pregnancy. One of the potentially related variables that they considered was the social support provided during pregnancy by the partner, family and friends. Pregnant women (N = 810) were therefore asked if they were married or if they lived with someone, as well as their perceptions in relation to the support received from family and friends. It was found that 75.8% of smokers were single (p < .01), with women being more likely to continue smoking during pregnancy if they did not have a partner. On the other hand, depressive symptomatology was significantly associated with women’s smoking status (p < .001). In addition, women with high scores on depressive symptomatology were more likely (p < .05) to report that they would not receive support from family and friends if they attempted to quit smoking (20.8%) than those with lower scores (7.2%). Cheng et al. (2016) examined the association between prenatal support provided by the partner and women’s smoking behaviour during pregnancy. For this purpose, 2,641 pregnant women were selected from two projects in the Boston area aimed at analyzing the impact of prenatal health and environmental exposure on maternal and infant health: the Viva Project and the ACCESS Project. To be eligible to participate in the Viva Project women had to be less than 22 weeks pregnant, while to participate in the ACCESS Project they had to be in mid- or late pregnancy. A total of 1,764 pregnant women were selected from the Viva Project and 877 pregnant women from the ACCESS Project. The Turner Support Scale was used to assess the support provided by the partner during pregnancy in both cohorts. In the Viva Project, but not in the ACCESS Project, women with low partner support were more likely to smoke during pregnancy (OR = 2.2). Cohen et al. (2016) evaluated a sample of 198 pregnant women from the US who had a partner, friends, or a family member who provided support related to pregnancy and infant care. Participants were asked to identify their primary source of support during pregnancy and, if they identified a partner, they were asked to complete seven questions drawn from the Norbeck Social Support Questionnaire (NSSQ) to assess the functionality and stability of the relationship and the amount of support provided by the partner. The researchers found no association between rates of smoking during pregnancy and partner support assessed with the NSSQ. However, 89.5% of women who smoked during pregnancy were single (p = .01). One study aimed to describe longitudinal patterns of maternal smoking before, during, and after pregnancy (Mumford & Liu, 2016). One of the variables considered to be potentially related to smoking trajectories was social support from friends and family during pregnancy and postpartum, as well as attendance at religious services. Mothers (N = 9,050) with children up to 6 years of age residing in the US were therefore asked to indicate all possible sources of support from a list of 13 possible personal relationships, which were grouped into the categories of family, friends, and professionals (clergy and health professionals). Women were more likely to be persistent smokers if they only attended religious services 1-2 times per year (OR = 0.58, p < .01) and were more likely to quit during pregnancy and postpartum if they attended religious services weekly (OR = 0.36, p < .05). Support from friends acted as a protective factor for not consuming tobacco during pregnancy (OR = 0.74, p < .05), while family support provided protection against resuming tobacco use postpartum (OR = 0.56, p < .01). Social Support and Smoking Cessation Only one study analyzed the relationship between social support and smoking cessation in women during pregnancy (see Table 2). Specifically, Dascăl et al. (2020) investigated the links between partner relationship characteristics and smoking cessation in women during pregnancy. These researchers examined a sample of 143 women residing in the USA who were fewer than 28 weeks pregnant, smokers or ex-smokers, who claimed to have a stable partner relationship. To assess the support provided by the partner during pregnancy for smoking cessation, the women were asked to complete the Partner Interaction Questionnaire (PIQ). The findings indicate that pregnant women with greater positive interactions with their partner, in relation to smoking cessation, were more likely to quit smoking during pregnancy (OR = 1.48). Table 2 Social Support and Smoking Cessation in Women during Pregnancy   Note. OR = odds ratio. *Statistically significant difference. Social Support and Maintenance of Abstinence from Smoking The qualitative study by Wen et al. (2015) was the only study that analyzed the relationship between social support and maintenance of abstinence from smoking in the postpartum period (see Table 3), examining the barriers and facilitators that prevent relapse and maintain abstinence in this period. Thirty US resident mothers who had children under 3 years of age and had quit smoking during a pregnancy were selected for study. One of the variables considered to be related to the maintenance of abstinence in the postpartum period was the social support provided by family and friends during this period. During the assessment, the mothers were asked a series of questions after giving birth: “What has helped you not to smoke?”; “Has anyone helped you not to smoke?”; “What things have made you want to go back to smoking?”. Participants reported that receiving support from family and friends helped them to successfully cope with cravings, and they identified the presence of social support as a factor influencing their smoking behaviour and related to stress reduction. Women who relapsed postpartum indicated that they were in contact with smokers and had easy access to cigarettes. They also felt that it is difficult to maintain abstinence after childbirth as they lost the social protection status associated with being pregnant or breastfeeding. Table 3 Social Support and Maintenance of Abstinence from Smoking in Women during the Postpartum Period   Note. *Qualitative study. Social Support and Smoking Relapse The study by Nguyen et al. (2012) was the second qualitative study considered and was the only one that examined the relationship between social support and smoking relapse in the perinatal period (see Table 4). The main objective was to determine which variables influence relapse in women who quit smoking during pregnancy, paying special interest to women’s social networks. For this purpose, a sample of 24 mothers in the USA who had quit smoking during pregnancy was selected for study. The support provided by family, friends, and coworkers during the postpartum period was assessed in terms of women’s perceptions. Content analysis revealed that it was difficult for women to remain abstinent when their partners smoked. After pregnancy, many women indicated that the strongest trigger for returning to smoking was a social environment including friends who smoked. They also described significant changes in their relationships with smokers in their social networks, losing connection with them and feeling judged. Table 4 Social Support and Smoking Relapse in Women during the Postpartum Period   Note. *Qualitative study. Table 5 Importance of Smoking Cessation or Partner’s Smoking Cessation during the Perinatal Period   Note. OR = odds ratio. *Statistically significant difference. Partner’s Smoking during the Perinatal Period This section includes studies that analyzed the importance of smoking cessation or continued smoking by the partner during the perinatal period in relation to women’s smoking (see Table 5). Page et al. (2012) aimed to analyze factors related to smoking in women postpartum. For this purpose, they evaluated 3,522 mothers who had given birth in the last year. In addition to assessing the smoking status of the partner in the postpartum period, the researchers considered other indicators of social support. Specifically, they examined a mother’s relationship with her baby’s father and the mother’s attendance at religious services, differentiating between mothers who attended one or more times a week, those who attended less than once a week and those who never attended. Women with a partner who smoked were more likely to relapse during that period (p < .001). In addition, women who attended religious services less than once a week and who did not have a partner were more likely to relapse postpartum (p < .001). In the UK, Prady et al. (2012) examined factors associated with postpartum relapse in a sample of 1,829 mothers of 9-month-olds and with different marital statuses. In addition to assessing women’s marital status at delivery and at 9 months postpartum (married, cohabiting, or single), these researchers also asked women about their partners’ smoking status during pregnancy and 9 months postpartum. At 9 months postpartum, 57.3% of women had relapsed. Of these, 51.4% were married, 59.7% were cohabiting, and 65.8% were single. Thus, cohabiting women, and especially single women, had a higher risk of relapse (cohabiting, OR = 1.40, p = .009; single, OR = 1.82, p < .001). In addition, women whose husbands had quit smoking during pregnancy, but relapsed postpartum, made up the highest risk group for relapse (OR = 11.4). Other study (Simmons et al., 2014) analyzed variables associated with postpartum relapse in a sample of 504 women in the USA who had quit smoking during pregnancy. The researchers considered as possible variables associated with relapse the smoking status of their partners and the support provided by the partners to quit smoking. Participants reported the smoking status of their partners before and after pregnancy (at one month and 12 months postpartum), and they completed the Partner Interaction Questionnaire (PIQ). The data showed that 27.2% of women relapsed at one month postpartum, and 39.9% relapsed at 12 months. Predictors of relapse at one month postpartum were not planning to breastfeed (p = .02), living with another smoker (p = .04), and not planning to quit smoking permanently (p < .001). Predictors of relapse at 12 months postpartum were having a partner who continued to smoke as in pregnancy (p < .006) and not intending to remain abstinent after giving birth (p = .002). In Spain, the only study analyzed was Román-Gálvez et al.’s (2018), who evaluated smoking prevalence and factors associated with smoking cessation in a sample of 463 pregnant women at fewer than 13 weeks’ gestation. One of the variables potentially related to cessation success/failure was the smoking status of the partner during pregnancy. For this purpose, interviews were conducted (before 13 weeks, at 24, and at 32 weeks of gestation), during which women were asked about their smoking status and their partners’. A total of 61.1% of the women (n = 122) reported having quit smoking during pregnancy. The smoking rate among mothers decreased from 36.1% before pregnancy to 14.1% during the first trimester, 12.4% in the second trimester, and 11.9% in the third trimester. However, there was only a minimal decrease in smoking prevalence among partners: 38.4% before pregnancy and 36.1%, 32.7% and 31.8% during the first, second and third trimesters of pregnancy. In addition, women whose partners smoked during pregnancy were found to be less likely to quit smoking during pregnancy (OR = 0.26). In the Netherlands, one study (Scheffers-van Schayck et al., 2019) analyzed the risk and protective factors in women who smoke before and throughout pregnancy, as well as in those who quit and those who relapse postpartum. For this purpose, the researchers asked the women what their partner’s smoking status was before pregnancy and whether there was any change in their smoking behavior, during, and after pregnancy. Of the women who smoked during pregnancy, 48.6% had partners who continued to smoke as much as or more than before (p < .001). In the postpartum period, 58.8% of women who relapsed had a partner who also smoked (p = .005). Women who smoked throughout pregnancy were more likely to have a partner who smoked during pregnancy (OR = 7.50) and were also more likely to relapse postpartum if their partner continued to smoke during that period (OR = 1.94). The findings obtained in the present review reveal the state of research on the social support associated with women’s smoking during the perinatal period in the last decade. First, we aimed to determine the role of social support in smoking or abstaining from smoking during pregnancy. The purpose of the support could be for the pregnant woman to quit smoking (Dascăl et al., 2020; Homish et al., 2012) or as help in solving daily problems or problems related to baby care (Cheng et al., 2016; Cohen et al., 2016; Maxson et al., 2012; Meghea et al., 2012; Mumford & Liu, 2016; Orr et al., 2012). Eight studies analyzed this aspect, seven during pregnancy (Cheng et al., 2016; Cohen et al., 2016; Dascăl et al., 2020; Homish et al., 2012; Maxson et al., 2012; Meghea et al., 2012; Orr et al., 2012), and one before and after delivery (Mumford & Liu, 2016). All of the studies found significant differences. The studies examined the influence of family, friend, and partner support, as well as attendance at religious services. The influence of family and friends support was analyzed in three studies (Homish et al., 2012; Mumford & Liu, 2016; Orr et al., 2012); the support provided by the partner was analyzed in six (Cheng et al., 2016; Cohen et al., 2016; Dascăl et al., 2020; Homish et al., 2012; Maxson et al., 2012; Orr et al., 2012); attendance at religious services was analyzed in two (Mumford and Liu, 2016; Page et al., 2012); and one study (Meghea et al., 2012) did not specify what was meant by social support. Thus, support provided by the partner is the variable receiving the most attention in this domain. Smoking during pregnancy was found to be associated with lack of social support from family and friends and not having a partner, and for those who did have a partner, with lack of positive interactions and negative or low partner support. Another aim of this review was to determine the influence of social support on maintenance of abstinence from smoking or relapse during the postpartum period. Two studies analyzed the influence of family and friends of pregnant women after giving birth (Nguyen et al., 2012; Wen et al., 2015), showing that family and friend support is related to a reduction in stress, which allows women to remain abstinent during this period. By contrast, the presence of a social environment of smokers is conducive to relapse, which was attributed to greater availability of tobacco. This indicates that there is a need to intervene in pregnant women’s environments to encourage them to stop smoking and, if this was not successful, to encourage women to ask their family/partners/friends not to smoke in their presence, to prevent the effects of passive smoking (Míguez & Pereira, 2021b). Although these studies are qualitative and conducted with small samples, both provide testimonies from women that reflect the difficulties they encounter in maintaining abstinence in the postpartum period. For example, in the study by Wen et al. (2015) one mother commented “When I really felt like smoking a cigarette it was because someone around me was smoking. When I was alone, I was fine,” making it clear the influence of others as a trigger for women’s desire to smoke. In the study by Nguyen et al. (2012) we can see similar testimonies: in relation to the couple “I married a smoker, and it is hard to quit when the person you live with smokes”; in relation to friendships “I went to my friend’s house. Her parents smoke, and when I go into that house there is a cloud of smoke...”; and in relation to the work environment “I worked in a company where almost all the workers smoked... whenever they had free time they went out to smoke. I felt alone and excluded because I was no longer part of the group.” The final objective of this review was to determine the influence of the smoking status of the partner on tobacco consumption in pregnant women. Different studies examined smoking by the partner during pregnancy (Román-Gálvez et al., 2018), during postpartum (Page et al., 2012), or at both stages (Prady et al., 2012; Scheffers-van Schayck et al., 2019; Simmons et al., 2014). All studies revealed significant differences, showing that women were more likely to smoke during pregnancy or relapse postpartum if their partners smoked. The only exception was in the study by Homish et al. (2012), who reported that, although having a partner who smokes is negatively associated with smoking cessation in early pregnancy, partner smoking was not related to smoking cessation in late pregnancy. The importance of partners not smoking during the perinatal period is therefore clear as, in addition to affecting the woman’s tobacco consumption, secondhand smoke can have adverse effects on both the mothers’ and children’s health (Action on Smoking and Health, 2014; Míguez & Pereira, 2021b). Several limitations to the present review must be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings. Firstly, only a few studies biochemically validated the abstinence of the participants (Homish et al., 2012; Orr et al., 2012), and most based their results on self-reported measures and thus may have overestimated the abstinence rates. Validation of self-reports of abstinence from smoking with biochemical measures is important, especially during pregnancy, as smokers tend to conceal their actual consumption (Becoña & Míguez, 2006; Míguez & Pereira, 2018). Another limitation is the lack of consensus regarding the definition and assessment of social support in this area. Thus in some studies it was defined as the existence of a smoking-free environment (Homish et al., 2012; Nguyen et al., 2012; Page et al., 2012; Prady et al., 2012; Román-Gálvez et al., 2018; Scheffers-van Schayck et al., 2019; Simmons et al., 2014), while in other studies it was defined as affection, empathy, or material help, provided by a partner, family, or friends (Cheng et al., 2016; Maxson et al., 2012; Mumford & Liu, 2016), as help provided during pregnancy and for childcare (Cohen et al., 2016; Meghea et al., 2012), as help with smoking cessation (Dascăl et al., 2020; Simmons et al., 2014; Wen et al., 2015), and other studies related it to being married or having a partner (Cohen et al., 2016; Orr et al., 2012; Page et al., 2012). In the absence of a common criterion for defining what is understood by the presence of social support during the perinatal period, it is difficult to interpret the study findings and to reach firm conclusions on the subject. On the other hand, social support was assessed using questionnaires (Cheng et al., 2016; Cohen et al., 2016; Dascăl et al., 2020; Maxson et al., 2012; Mumford & Liu, 2016; Simmons et al., 2014) or interviews, from which women reported on their marital status, whether their partner, family, and friends smoked, and their perception regarding the help provided by their family and friends (Homish et al., 2012; Meghea et al., 2012; Nguyen et al., 2012; Orr et al., 2012; Page et al., 2012; Prady et al., 2012; Román-Gálvez et al., 2018; Scheffers-van Schayck et al., 2019; Simmons et al., 2014; Wen et al., 2015). The lack of a common method of assessing social support makes it difficult to compare and analyze the various studies. It is worth mentioning that no studies were found that examined the indirect influence of social support on perinatal smoking, so it is unknown whether social support might mediate other smoking-related variables (e.g., stress, anxiety, depression). On the other hand, very few interventions were found that addressed the role of social support in helping women to quit smoking. For this reason, future research should examine the indirect influence of social support and the effectiveness of psychological interventions based on social support for smoking cessation during pregnancy. Despite these limitations, this review provides relevant information on the influence of the partner’s smoking on the woman’s consumption during the perinatal period, an aspect to be taken into account in smoking cessation interventions. In addition, this is the first review that analyzes the relevance of social support in a broad sense for women to quit smoking during this period, and not exclusively focused on partner support as other reviews have done (e.g. Hemsing et al., 2012; Orton et al., 2018; Pollak et al., 2006). On the other hand, this study not only analyzes the relationship between social support and smoking during pregnancy, but also with spontaneous cessation and with relapse and maintenance of abstinence during the postpartum period, providing a more global and complete view of the relationship. The data obtained in this review suggest that lack of social support from family and friends, lack of positive interactions with partners, a low level or negative support from partners, and not having a partner are all related to smoking during pregnancy. In addition, women with a partner who smokes tend to continue to smoke during pregnancy and relapse postpartum, and it is therefore important that the partner also stops smoking during the perinatal period. The specific treatments carried out with the aim of helping women to quit smoking during this period should also consider whether or not the partner smokes and, if necessary, the partner should also be offered support with smoking cessation. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Posse, C. M., Val, A., Míguez, M. C. (2025). Social support and women’s smoking during the perinatal period: A systematic review. Clinical and Health, 36(1), 25-35. https://doi.org/10.5093/clh2025a4 References |

Cite this article as: Posse, C. M., Val, A., and Míguez, M. C. (2025). Social Support and WomenŌĆÖs Smoking during the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review. Clinical and Health, 36(1), 25 - 35. https://doi.org/10.5093/clh2025a4

Correspondence: mcarmen.miguez@usc.es (M.C. Míguez).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS