What Mechanisms do Children and Adolescents with Chronic Pain Use to Manage their Friendships? A Review of the Literature

[ÂżQuĂ© mecanismos utilizan los niños y adolescentes que padecen dolor crĂłnico para gestionar sus amistades? RevisiĂłn de la literatura cientĂfica]

Imma Beneitez, Eulàlia Hernández, Rubén Nieto, and Mercè Boixadós

Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2020a2

Received 19 June 2019, Accepted 27 September 2019

Abstract

This study review the available literature about friendships of children and adolescents with chronic pain, focusing on the mechanisms they use to face challenges in their relationships and the theories studies use to address this topic. We conducted a search in PubMed, PsycINFO, and WOS from inception to August 2017. We included peer-reviewed primary studies with a specific subgroup analysis of friendships in children and adolescents (6-18 years old) with the followingconditions: lower limb pain, neck and shoulder pain, back pain, abdominal pain, headache and migraines, fibromyalgia, and complex regional pain syndrome. Twenty empirical articles were selected. From these studies, 18 mechanisms and 6theories were identified. Studies show a high variability in the methodologies employed, as well as in the way they define friendships experience. Finally, very few of the studies selected are theory-based.

Resumen

Este estudio revisa las publicaciones científicas disponibles sobre las amistades de niños y adolescentes que padecen dolor crónico centrándose en los mecanismos que utilizan para afrontar los desafíos que sus relaciones les plantean y las teorías utilizadas por los estudios para abordar este tema. Llevamos a cabo una búsqueda en PubMed, PsycINFO y WOS desde los inicios hasta agosto de 2017. Incluimos estudios primarios de revisión de pares con un subgrupo de análisis específico de las amistades en niños y adolescentes (entre 6 y 18 años), con las siguientes condiciones: dolor en las extremidades inferiores, dolor de cuello y hombros, dolor de espalda, dolor abdominal, dolor de cabeza y migrañas, fibromialgia y síndrome de dolor regional complejo. Se seleccionaron 20 artículos empíricos, a partir de los cuales se detectaron 18 mecanismos y 6 teorías. Los estudios muestran gran variabilidad en la metodología utilizada, así como en el modo de definir la experiencia de las amistades. Por último, muy pocos de los estudios elegidos están basados en la teoría.

Palabras clave

Dolor pediátrico, Relaciones sociales, Resiliencia, Factor de riesgo, Psicosocial, TeorĂasKeywords

Pediatric pain, Social relationships, Resilience, Risk factor, Psychosocial, TheoriesCite this article as: Beneitez, I., Hernández, E., Nieto, R., & Boixadós, M. (2020). What Mechanisms do Children and Adolescents with Chronic Pain Use to Manage their Friendships? A Review of the Literature. ClĂnica y Salud, 31(1), 27 - 45. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2020a2

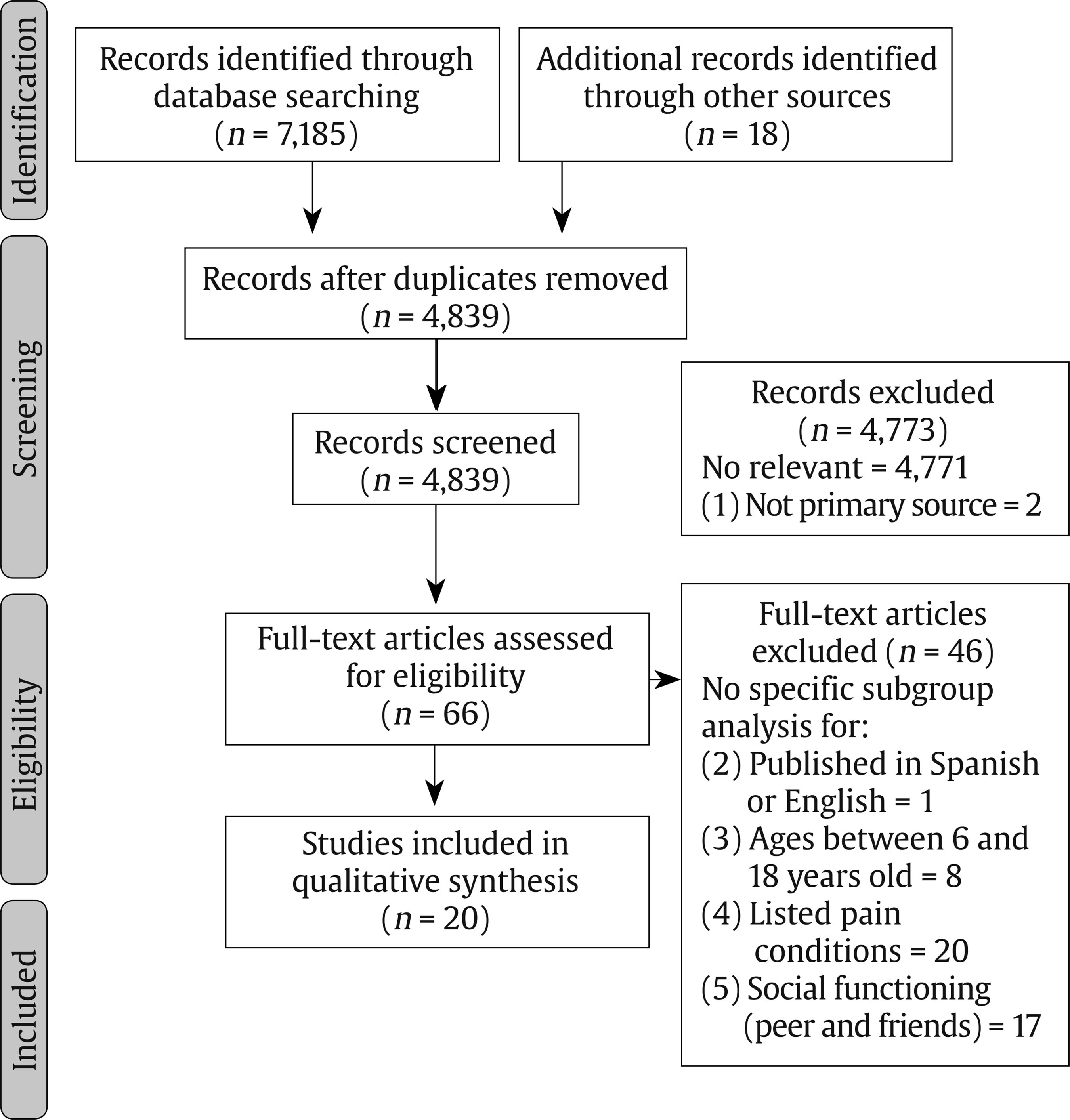

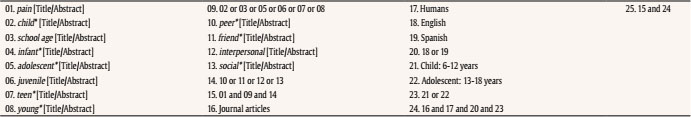

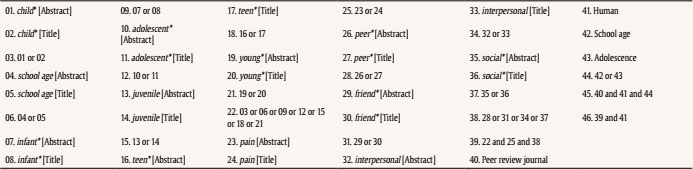

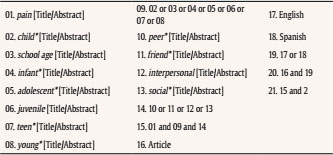

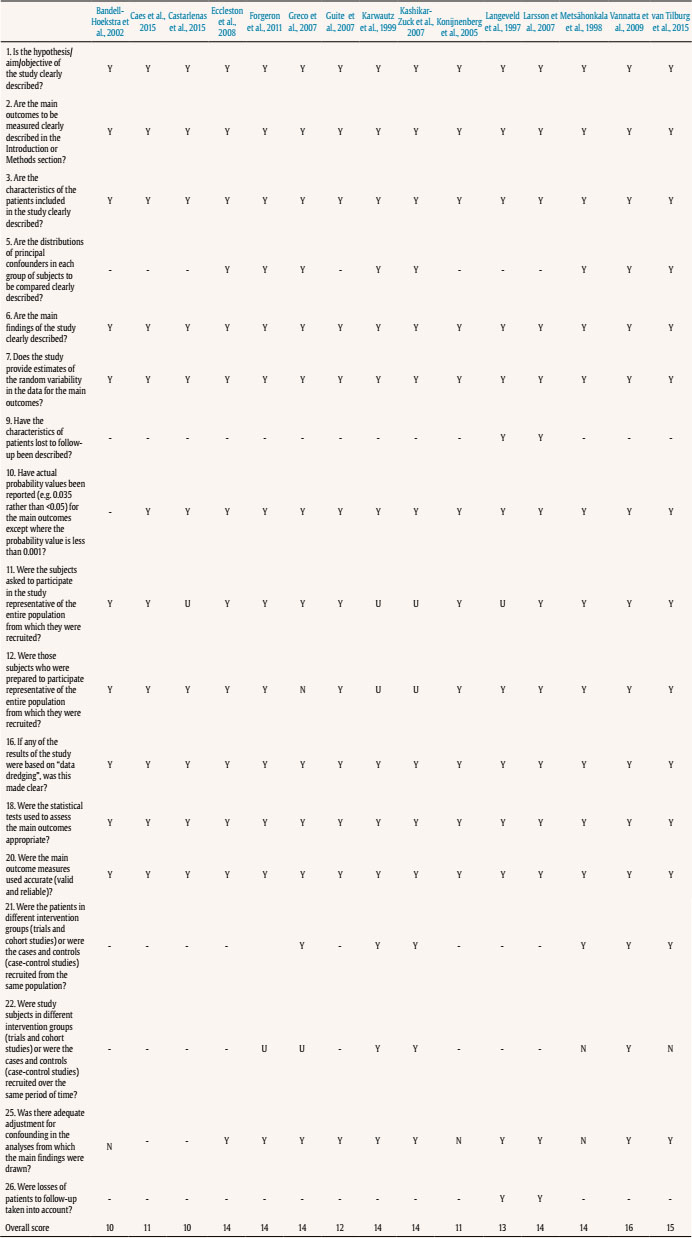

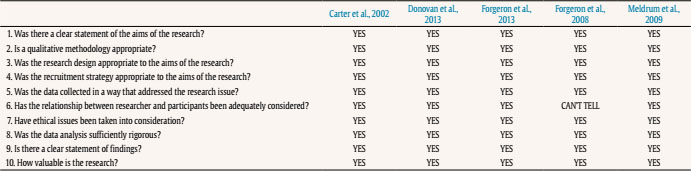

ibeneitez@uoc.edu Correspondence: ibeneitez@uoc.edu (I. Beneitez).Between 11 and 38% of children and adolescents experience recurrent or chronic pain, depending on the pain problem studied (King et al., 2011). These conditions affect children and adolescents’ quality of life (Huguet & Miró, 2008) and other domains of their lives, such as sleep habits and school or social functioning (Palermo, 2000; Petersen, Hagglof, & Bergstrom, 2009; Roth-Isigkeit, Thyen, Stöven, Schwarzenberger, & Schmucker, 2005). The negative effects include school absences due to pain (Konijnenberger et al., 2005; Roth-Isigkeit et al., 2005) and reductions in their participation in extracurricular activities (including sports, getting together with friends, and other social activities) (Konijnenberger et al., 2005; Langeveld, Koot, & Passchier, 1997). These children and adolescents have a deterioration in their friendships (Fales & Forgeron, 2014; Forgeron et al., 2010; Kashikar-Zuck et al., 2007; Stinson et al., 2014) (have fewer friends, experience social isolation, and are more likely to be rejected and chosen less frequently as best friends). In front of this situation, they have to face peer and close friend relationship challenges (Forgeron, et al., 2010; Greco, Freeman, & Dufton, 2007) such as: feeling of being different from others, stigmatized (Meldrum, Tsao, & Zeltzer, 2009), or bullied (Metsähonkala, Sillanpää, & Tuominen, 1998), having to face disbelief from others (Carter, Lambrenos, & Thursfield, 2002; Fleischman, Hains, & Davies, 2011; Forgeron, Evans, McGrath, Stevens, & Finley, 2013; Forgeron & McGrath, 2008; Meldrum et al., 2009), and perceiving others’ behaviors as non-supportive (Forgeron et al., 2013; Forgeron et al., 2011; Meldrum et al., 2009; Merlijn, et al., 2003). Children and adolescents with chronic pain have to face these friendships challenges through the use of different mechanisms. Following Cousins (Cousins, Kalapurakkel, Cohern, & Simmons, 2015), we use the term “mechanisms” to refer to the cognitions, affects, and behaviors displayed by children and adolescents in their friendships. Each mechanism can promote social isolation or involvement and might represent a risk or resilience factor, respectively, according to the resilience-risk model in pediatric pain proposed by the same author. Involvement in positive peer and friend relationships have been found to be associated with functional ability and might represent a resilience factor system to help them manage pain (Cousins et al, 2015; Fleischman et al., 2011; Sinclair, Meredith, Strong, & Feeney, 2016; Stinson et al., 2014). On the contrary, when adolescents are not involved socially, the lack of this support is a source of stress (Donovan, Mehringer, & Zeltzer, 2013; Fleischman et al., 2011; Kashikar-Zuck et al., 2007). Social functioning has been identified as essential for health and quality of life (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2011). In this vein, friendships are significant persons in adolescents’ social networks and important sources of influence on health and wellbeing (La Greca, Bearman, & Moore, 2002). However, the available literature does not provide an identification and summary of the mechanisms that enhance and hinder peer and friend relationships in children and adolescents with chronic pain. Further investigation in the field of supportive friendships and the mechanisms involved to promote them will help to develop and test innovative approaches to chronic pain prevention and treatment (Fales & Forgeron, 2014; Yeung, Arewasikporn, & Zautra, 2012). There are several theories that explain the nature of social relationships (including peer and friends) and how these occurs. The Social Learning theory (Bandura, 1977) and the Operant Learning theory (Skinner, 1953) explain reinforcement and modelling processes involved in social development. Two other theories that might also explain social behaviors and have been applied to the field of pain are Lazarus’ theory (Lazarus, 1966), that explains how individuals cope to stressful situations, and the Fear-Avoidance Model (FAM) (Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000) that explains the avoidance behavior based on fear. Recently, the Social Communication Model of Pain (SCP) (Craig, 2009; Craig, 2015) has been applied to the pediatric chronic pain (Forgeron & King, 2013) arguing that the expression of pain by children and adolescents may affect the way others (peers and friends) interpret (decodee) and respond to their pain (act). At the same time, peers and friends’ responses to children or adolescents’ pain expression may positively or negatively affect their pain experience. In other words, as mentioned above, their relationships could be a source of support or stress, and the result of this cycle of interactions may influence social interactions of children and adolescents with chronic pain (interpersonal factors) and the pain intensity perceived (intrapersonal factors) (Forgeron & King, 2013). Therefore, this article aims to: first, describe the study characteristics of the current evidence available in relation to peer and friend relationships in children and adolescents with chronic pain; second, identify (where possible) the mechanisms they use to manage these relationships and whether they tend to be related to involvement or isolation; and third, explore the psychological theories studies use to explain social behavior. Literature Search and Data Sources We conducted an electronic search in each of the following three databases: PsycINFO, PubMed, and Web of Science from their origins until 15 August 2017. PsycINFO and PubMed are two of the main databases used in the fields of Psychology and Medicine (Baker Pistrang, & Elliott, 2015). Additionally, we considered to conduct a search with the multidisciplinary academic database Web of Science, as friendships topic might be achieved by other disciplines. We used the following combinations of terms: “pain” and “child* / infant / adolescent* / juvenile / teen* / young* / school age” and “peer* / friend* / interpersonal / social*” in the title and/or abstract of the articles. Some of these terms have been previously used in searches from salient reviews in the field of pediatric chronic illnesses, including pain (Forgeron et al., 2010; Kohut, Stinson, Giosa, Luca, & van Wyk, 2014; Lewandoski, Palermo, Stinson, Handley, & Chambers, 2010; Tong, Jones, Craig, & Grewal, 2012). The full search strategy is described in detail in Table S1, S2 and S3. Study Selection Two of the authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all the citations. They were blind to authors and institutions, and all the articles that met the criteria were full-text reviewed. In addition, reviewers examined reference lists of all the articles included in order to identify any additional articles that might have been missed by the search strategy. Articles were selected using the following inclusion criteria: (C1) Primary sources (e.g., not meta-analysis, reviews, letters, or commentaries) (C2) Published in English or Spanish. (C3) Targeted school-aged children (6-12 years old) and/or adolescents (13-18 years old). (C4) Children or adolescents presenting one of the following chronic pain conditions: lower limb pain, neck and shoulder pain, back pain, abdominal pain, headache and migraines, fibromyalgia, and complex regional pain syndrome. Therefore, we did not include pain due to medical conditions, medical procedures, or disease. (C5) Included a specific subgroup analysis or specific attention to peer and friend relationships. Any disagreement was discussed until agreement was reached. Inter-rater agreement for full-text screening was 93% (Cohen, 1968). Quality Assessment The heterogeneity of study designs in the articles selected for the review (descriptive, case-control, and cohort) and the nature of studies (no intervention studies or randomized controlled trials were found) made it not possible to follow the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & PRISMA Group, 2009) and assess the quality of the methodology with a unique structured quality scale. To overcome this problem and do a proper assessment according to the nature of studies, we followed the solution adopted by Jarde (Jarde, Losilla, & Vives, 2012) by using a different checklist for each study design. Therefore, the methodological quality of quantitative studies was reviewed using Downs and Black’s (1998) checklist, and for qualitative studies, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2013) was used. The quality appraisal for each study is described in Table S4 and S5. No study was rejected due to low methodological quality. Data Extraction Predefined data were extracted by one of the authors: authors and year of publication, participants and chronic pain condition, study design, primary focus of the study, and instruments and measures used to assess peer and friend relationship characteristics (Table 1). Detailed data about the mechanisms involved in peer and friend relationships were extracted (Table 2), as well as whether a theory was used to explain these relationships. A second reviewer checked the information selected through each process, and a consensus was reached if there were any discrepancies. Table 1 Reviewed Studies   Note. CP = chronic pain; RP = recurrent pain; CRPS = complex regional pain syndrome; RAP = recurrent abdominal pain; JPFS = juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome; CSC = cross-sectional cohort; PC = prospective cohort; CSD = cross sectional descriptive; CC = case-control; LD = longitudinal descriptive; Q = quantitative; QL = qualitative. During the data extraction process, we contacted one author in order to obtain the full-text version of one of the articles selected. However, when some data were missing (i.e., mean age or standard deviation, or specific items of questionnaires used), we did not attempt to contact authors for further information or search for extra data. After reviewing the articles, and to fulfill the second objective involving the identification of mechanisms, we followed this four-step process: first, to detect the behaviors, cognitions, affects, or even strategies that are cited or described in some way in the study; second, to check whether strategies were attributed to the child or adolescent in pain or to his peers and friends; third, to collect and organize data in different categories according to their similarity; and fourth and finally, to assign a label to each category in order to define and differentiate them as mechanisms. An electronic database search yielded 7,185 citations, and 18 additional studies were selected from the reference lists examined and hand searched. After accounting for duplicates, titles and abstracts of the 4,839 remaining articles were screened for relevance, and non-primary sources (C1) were excluded. Next, we applied the aforementioned criteria (C2-C5). Consequently, 20 studies (Bandell-Hoekstra et al., 2002; Caes, Fisher, Clinch, Tobias, & Eccleston, 2015; Carter et al., 2002; Castarlenas et al., 2015; Donovan et al., 2013; Eccleston, Wastell, Crombez, & Jordan, 2008; Forgeron et al., 2013; Forgeron et al., 2011; Forgeron & McGrath, 2008; Greco et al., 2007; Guite, Logan, Sherry, & Rose, 2007; Karwautz et al., 1999; Kashikar-Zuck et al, 2007; Konijnenberg et al., 2005; Langeveld et al., 1997; Larsson & Sund, 2007; Meldrum et al., 2009; Metsähonkala et al., 1998; Vannatta et al., 2008; van Tilburg et al., 2015) met inclusion criteria and were included in the review (Figure 1). The two articles excluded for not being primary sources (C1) were fully reviewed to scan their reference lists because one of them was an outstanding systematic review, and the other was a commentary related to the aims of our study. All the 8 studies excluded by C3 have adult participants, and none was excluded for including children less than 6 years old. Those studies that did not specify the chronic pain condition and researched chronic pain in general (Fleischman et al., 2011; Forgeron, MacLaaren, Chorney, Carlson, Dick, & Plante, 2015; Merlijn et al., 2003) were excluded by C4. Using the same criteria, studies that clearly included pain due to disease or pain conditions not listed (such as the gynaecologic pain, that was mixed with other pain condition listed) were also excluded (Simons, Logan, Chastain, & Stein, 2010). Specific subgroup analysis or specific attention to peer and friend relationships (C5) was sometimes embedded into the broad term of social functioning, yet in studies selected we assured that friends and peers were cited and considered in some way. According to objectives, results are presented in three sections: study characteristics, mechanisms, and psychological theories identified. Study Characteristics Table 1 describes and summarizes the characteristics of the studies reviewed.

Chronic pain conditions addressed most in studies were: abdominal pain (Bandell-Hoekstra et al., 2002; Caes et al., 2015; Carter et al., 2002; Castarlenas et al., 2015; Eccleston et al., 2008; Forgeron et al., 2013; Forgeron et al., 2011; Greco et al., 2007; Larsson & Sund, 2007; Konijnenberg et al., 2005; van Tilburg et al., 2015), headache or migraines (Caes et al., 2015; Carter et al., 2002; Castarlenas et al., 2015; Donovan et al., 2013; Eccleston et al., 2008; Guite et al., 2007; Konijnenberg et al., 2005; Langeveld et al., 1997; Larsson & Sund, 2007; Meldrum et al., 2009; Metsähonkala et al., 1998; Vannatta et al., 2008), back pain (Caes et al., 2015; Carter et al., 2002; Eccleston et al., 2008; Forgeron et al., 2011; Forgeron & McGrath, 2008; Larsson & Sund, 2007), limb pain (Caes et al., 2015; Castarlenas et al., 2015; Forgeron & McGrath, 2008; Larsson & Sund, 2007), and musculoskeletal pain (Forgeron et al., 2013; Guite et al., 2007; Konijnenberg et al, 2005). Samples sizes ranged from 5 to 2360. Some of the studies included additional sources of information besides children and adolescents, such as clinicians (Donovan et al., 2013), caregivers (Donovan et al., 2013; Guite et al., 2007), and teachers (Greco et al., 2007; Kashikar-Zuck et al., 2007; Vannatta et al., 2008). Nine of the 20 studies (Forgeron et el., 2013; Forgeron et al., 2011; Greco et al., 2007; Karwautz et al., 1999; Kashikar-Zuck et al., 2007; Konijnenberg et al., 2005; Metsähonkala et al., 1998; Vannatta et al., 2008) included a comparison group of children and/or adolescents without chronic pain. Children and adolescents were recruited from clinical services in the majority of the studies, but in some cases, they were also recruited from the community (Caes et al., 2015; Donovan et al., 2013; Metsähonkala et al., 1998) or school (Bandell-Hoekstra et al., 2002; Castarlenas et al., 2015; Greco et al., 2007; Langeveld, Koot, Loonen, Hazebroek-Kampscheur, Passchier, 1996; Larsson & Sund, 2007).

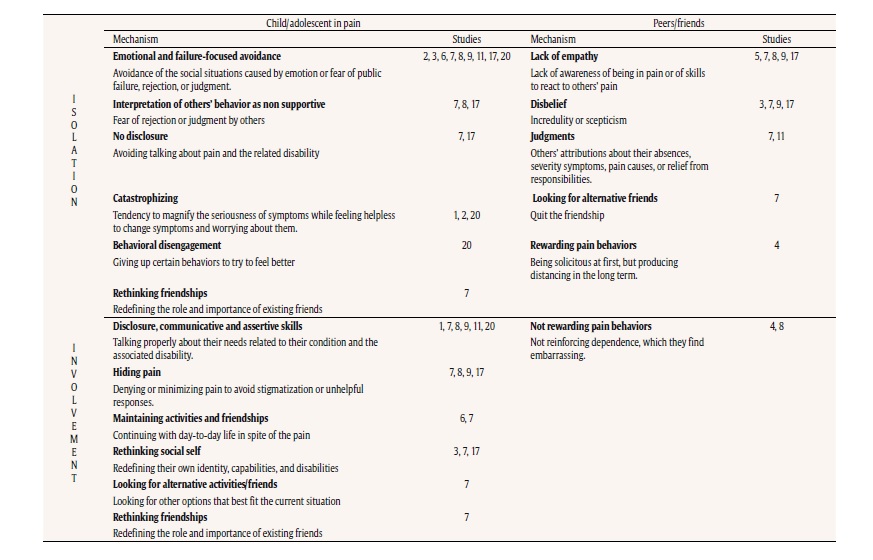

Considering the use of standardized instruments, only a few studies used the same instruments: Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire (BAPQ) (Eccleston et al., 2005) to assess self-perception development (Caes et al., 2015; Eccleston et al., 2008), Revised Class Play (RCP) (Masten, Morison, & Pellegrini, 1985) in combination with Three Best Friends (TBF)/Best Friends Nomination (BFN) (Bukowski & Hoza, 1989) to describe patterns of social behavior and reciprocated friendships (Kashikar-Zuck et al., 2007; Vannatta et al., 2008) and the Quality of Life Headache in Youth questionnaire (QLH-Y) (Langeveld et al., 1996) to assess social interaction with peers (Bandell-Hoekstra et al., 2002; Langeveld et al., 1996). In addition, three studies used specific pain instruments (Caes et al., 2015; Castarlenas et al., 2015; Eccleston et al., 2008), and one of them used instruments oriented toward health and illness in a broad sense (Konijnenberg et al, 2005). The rest of the instruments were related to the social area (classmate’s pain experience (Castarlenas et al., 2015), peer relationships (Bandell-Hoekstra et al., 2002; Langeveld et al., 1996; Price, Spence, Sheffield, & Donovan, 2002), perceived social support-friend (Procidano & Heller, 1983), social acceptance (Asher, Singleton, Tinsley, & Hymel, 1979; Harter, 1988; Vorst, 1990), social experiences (Crick & Bigbee, 1998; social skills (Gresham & Elliot, 1990), role and social limitation due to physical problems (Landgraf, Abetz, & Ware, 1996), illness behavior (Walker & Zeman, 1992), and pain response (Walker, Smith, Garber, & van Slyke, 1997). In parallel, ten studies used their own techniques designed for the study (focus group, workshop, qualitative and in depth interviews, or paper-and-pencil/internet surveys) (Carter et al, 2002; Donovan et al., 2013; Forgeron et al., 2013; Forgeron & McGrath, 2008; Karwautz et al., 1999; Larsson & Sund, 2007; Meldrum et al., 2009; Metsähonkala et al., 1998). Mechanisms Once we identified the mechanisms, following the process described above (methods section), we classified them in two main categories called isolation or involvement mechanisms, depending on their consequences: a tendency to isolate a child or adolescent in pain from his/her peers or friends, or the opposite, a tendency to involve these children with their peers or friends. Table 2 presents a detailed list and description of the mechanisms involved in peer and friend relationships. As mentioned above, the mechanisms arose mainly from qualitative data, whereas only two mechanisms were based on quantitative data: catastrophizing and rewarding pain behaviors (Bandell-Hoekstra et al., 2002; Caes et al., 2015; Castarlenas et al., 2015; van Tilburg et al., 2015). The majority of the mechanisms were captured from the experiences of children or adolescents with chronic pain with their peers or friends. Two mechanisms, Looking for alternative friends and Rewarding pain behaviours (both from peers/friends’ perspective), were exclusively taken from studies that examined the impact of the chronic pain on friendships, including healthy adolescents’ point of view (Castarlenas et al., 2015; Forgeron et al., 2013). We identify the mechanisms described in 13 articles. The other six studies (Karwautz et al, 1999; Kashikar-Zuck et al., 2007; Konijnenberg et al., 2005; Langeveld et al., 1996; Larsson & Sund, 2007; Metsähonkala et al., 1998; Vannatta et al., 2008) provided complementary information about social functioning. Psychological Theories In relation to our third objective, from all the studies selected, we identified 3 of the 5 theories cited in the introduction section to describe and explain the relationships between being in pain and friendships. Additionally, three other theories were identified. And only three of the studies were clearly theory-based, with a theory guiding the study (Bandell-Hoekstra et al., 2002; Caes et al., 2015; Forgeron et al., 2011). The Social Learning theory (Bandura, 1977) was cited in one study (Guite et al., 2007) as a general reference in the background section, and it was related to withdrawal from regular activities or social contact. Due to their activity restriction, children and adolescents in pain had fewer opportunities to develop social skills and salient behavioral models to learn and imitate; therefore, they would show delayed social development. As variables, the authors analyzed functional disability and self-perceived competence (including social acceptance), and the latter was an important aspect to understand the relationship between pain and functional disability, as the theory postulates. Lazarus’ (1966) Theory about coping with stress appeared in two articles (Bandell-Hoekstra et al., 2002; Forgeron & McGrath, 2008). One of the studies (Bandell-Hoekstra et al., 2002) describes the pain coping strategies (such as seeking social support, internalizing and externalizing behaviours and so on) to manage stressful situations (pain) and analyzes them in terms of pain severity. Authors based their study in this theory and concluded that pain coping strategies have an important impact on pain severity. The other article (Forgeron & McGrath, 2008) discusses whether adolescents who are not interested in seeking peer support could appraise sharing their pain as somehow shameful, and thus feel incompetent in their ability to discuss their pain with others and consequently do not use this pain coping strategy (and lose the opportunity to use social support as a resource to cope with stress). The study only assessed a few variables related to the theory (such as perceived social support, social anxiety, self-perception, coping, and disability). Direct relationships among these variables remain unclear, and authors explicitly cited the theory only in Discussion sections (Forgeron & McGrath, 2008). The FAM (Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000) was used as the basis for one study (Caes et al., 2015) that tested some of the variables in this model. Authors showed that high pain-related anxiety is associated with greater disability in adolescents (in general), and with a self-perception of greater impairment in social functioning particularly in girls. Therefore, authors concluded that social functioning should be explored as an integral part of a Fear Avoidance Model. Although it was not previewed according to previous literature, we identified three other theories that might also be used to explain friendships. These are the Theory of Interdependence (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978) and the Theory of Equity (Walster, Walster, & Berscheid, 1978), both based on a cost-benefit ratio, and the Social Information Processing (SIP) (Crick & Dodge, 1994) model to interpret social situations. The Theory of Interdependence (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978) and the Theory of Equity (Walster et al., 1978) were used in one study (Forgeron et al., 2013) to partially explain the results, specifically the decrease in the time spent with friends based on a cost-benefit ratio. In other words, children and adolescents in pain spend less time with close friends because they need more time to fulfil their needs related to the pain condition, and, consequently, their friends look for alternative partners. The SIP (Crick & Dodge, 1994) model was used in one study (Forgeron et al., 2011) to lead the study and to assess, through narrative vignettes, whether the interpretation of friendship interactions was supportive or non-supportive. Results reflected a tendency among adolescents with chronic pain to interpret non-supportive social situations with close friends as more distressing. In relation to the first objective, there is great variability in pain conditions, samples, and sources of information, as well as in the designs, methodologies, instruments, and variables measured. Moreover, features related to chronic pain (i.e., frequency, intensity, disability) are not uniformly described or used to explain friendships. Furthermore, variables related to this topic are usually assessed as secondary measures rather than primary outcomes. All of these considerations make it difficult to compare results, or even to summarise them with details and within an integrative discourse. Although the quality assessment indicates that all studies included are methodologically acceptable, our second objective is not fully met. This was mainly done for two reasons. First, given that only six out of the 20 selected articles focus on peer and friend relationships, our targeted topic (peers and friends) is only partially addressed in the studies, or it is included in a general category of social functioning (which might include family, teachers, etc.). The second reason is that the studies reviewed do not clearly identify and cite the mechanisms as such, and therefore the process of extracting and identifying mechanisms carried out in the present study might sometimes be based on implicit information or on authors’ judgements.To the best of our knowledge, until 2002 there were no studies that explicitly or implicitly addressed mechanisms involved in friendships of children and adolescents with chronic pain. Since then, this area of study has grown slightly, and has been mainly developed and described by Forgeron’s studies, as shown in three of the selected articles (Forgeron & McGrath, 2008; Forgeron et al., 2011; Forgeron et al., 2013) and three others that has been excluded (Fales & Forgeron, 2014; Forgeron et al, 2015; Forgeron et al., 2010) because they do not fully meet the inclusion criteria. The majority of the studies address two mechanisms: Emotional and Failure-focused avoidance and Disclosure, communicative, and assertive skills. The first one leads to isolation by promoting the avoidance of the social situations that might expose the child or the adolescent to uncomfortable feelings, or to others’ lack of empathy, disbeliefs and judgments. On the contrary, the second mechanism promotes the involvement of the children or the adolescent by talking properly with others about their needs. It might be a good mechanism to seek social support which, in turn, could act as a protective factor. Among the mechanisms that alienate children and adolescents from others are Interpretation of others’ behavior as non supportive, Catastrophizing and No disclosure, that might appear interrelated. In other words, fear of rejection and judgements and being worried and keep on thinking about the pain, might be related to not disclosing about the pain condition and related disability. In contrast to that, Hiding pain and Maintaining activities and friendships (sharing common interests) have a protective role at first when adolescents struggle to be and act normal when dealing with their pain (Forgeron & McGrath, 2008; Forgeron et al, 2013; Meldrum et al., 2009). Both might be a good distraction from pain and help them to gain confidence and engage in disclosure. In some cases, and particularly in the onset of chronic pain, they are no longer able to identify with the same activities they did before, activities that had helped them to define who they are; consequently, they have to Rethink their social self. This leads to identifying their current needs and displaying more adaptive mechanisms (Forgeron et al, 2013). Only one involvement mechanism was identified from peers and friends behavior: Not rewarding pain behaviors (not focusing on pain). It supports appropriateness of behaviors, cognitions, or responses that encourage children to enact adaptive behaviours (Castarlenas et al., 2015; Forgeron et al., 2011). The majority of mechanisms were identified in more than one study. However, some of them are identified just once. Among them, and promoting isolation, we found Behavioral disengagement, Rewarding pain behaviors, and Looking for alternative friends (from friends and peers perspective). On the other hand, and as a mechanism than can promote involvement, we identified Looking for alternative activities/friends behavior. Finally, the Rethinking friendships mechanism has been related to both involvement and isolation. Social peers and friends functioning occurs essentially in a relational and dynamic situation. Most studies only provide static data from the point of view of one of the actors involved (i.e., a child or adolescent with chronic pain, a healthy peer, parent, practitioner, and teacher). As Table 2 shows, there is little evidence about mechanisms involved from peers and friends’ perspective. The absence of data might be due to the fact that few articles include the perspective of healthy participants. Regarding the current evidence in relation to the third objective, only 3 studies are theory-driven, and thus follow the FAM model (Caes et al., 2015), the SIP model (Forgeron et all, 2011), and the Lazarus’ theory (Bandell-Hoekstra et al., 2002). As commented in the introduction section, social support help an individual to cope with stressful situations, such as pain. Children and adolescents who suffer from more pain severity tend to cope with stressful situations by seeking social support, and showing internalizing and externalizing behaviors, among others (Bandell-Hoekstra et al., 2002). If they do not feel competent about their skills for discussing pain (cognitive appraisal from Lazarus’ theory), then they will think that nothing can be done to change the situation (Forgeron & McGrath, 2008). The SIP model (Crick & Dodge, 1994) explains how supportive and non-supportive interpretation of social situations takes place, showing that adolescents with chronic pain have a tendency to interpret non-supportive social situations as more distressing (Forgeron et al., 2011). And finally, FAM (Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000) explains how pain-related anxiety is associated with greater impairment in social functioning. In other words, these three theories are those that best contribute to explaining what is happening in peer and friend relationships of these children and adolescents. Interpretation of other’s behavior as supportive or non-supportive and appraisal of own competence to discuss pain explain which mechanism would be chosen to deal with stressful situations: the ones listed in Table 2 that promotes involvement or isolation. Similarly, pain-related anxiety might play an important role as mediator in the mechanism used to manage the stressful situation and, consequently, affect the level of impairment of social functioning. It is worth noting that the Social Communication Model of Pain (Craig, 2009; Craig, 2015), which postulates that interpersonal factors (such as peer and friend relationships) are relevant in understanding individuals’ pain experiences and expressions, although it has been used previously in the paediatric pain context (Forgeron & King, 2013), has not been cited in any article reviewed. The literature on recurrent and chronic pain usually merges different pain problems, and so it is possible that our exclusion criteria (pain problems listed) limited our search to a reduced number of studies to review. Likewise, few studies assess peers and friends’ behavior without clearly differentiating it from behavior of other people in a child’s environment (e.g., teachers). In another vein, there might be a certain degree of subjective bias and overlapping in the definition of mechanisms as they are extracted and formed based on author judgments. Finally, as we have focused our search on the most salient ones in psychology and health field databases, it is possible that our review has not captured all empirical studies on direct or indirect aspects of peer and friend relationships in children and adolescents with chronic pain listed conditions. From this review we can draw two main conclusions. First, peer and friend relationships in children and adolescents with chronic pain are not a uniform experience, and are contextually specific. However, there are a few common trends: impairment in activities and contact with peers and friends (i.e., fewer friends, isolation); self-identity difficulties, feeling different from others; and others’ lack of understanding and disbelief about the pain condition. Consequently, they use similar mechanisms to deal with these difficulties. Each of these mechanisms leads children and adolescents to isolation from or involvement in their peer and friend relationships, as has been described. Second, traditionaly, literature suggests conducting theory-driven research to advance (Karmiloff-Smith & Inhelder, 1974). However, according to our results, most of the articles only cite a theory as a reference, and just three of them are theory driven (Bandell-Hoekstra et al., 2002; Forgeron et al, 2011; Pluye et al., 2011). Moreover, only Lazarus theory was cited in more than one study and was used to provide a comprehensible peer and friend relationships explanation. In any case, none of the studies were designed to test a specific theory. Finally, assuming that mechanisms are dynamic, modifiable, and potentially active processes when confronting pain (Cousins et al., 2015), these findings should be taken into account when designing and planning interventions aimed toward strengthening some mechanisms (e.g. Disclosure, communicative, and assertive skills) and prevent from others (e.g. Emotional and failure-focus avoidance), in order to promote social involvement in adolescents with chronic pain. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Beneitez, I., Hernández, E., Nieto, R., & Boixadós, M. (2020). What mechanisms do children and adolescents with chronic pain use to manage their friendships? Areview of the literature. Clínica y Salud, 31(1), 27-45. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2020a2 Funding: This study was supported by a doctoral grant from the UOC PhD Doctoral Fellowship References |

Cite this article as: Beneitez, I., Hernández, E., Nieto, R., & Boixadós, M. (2020). What Mechanisms do Children and Adolescents with Chronic Pain Use to Manage their Friendships? A Review of the Literature. ClĂnica y Salud, 31(1), 27 - 45. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2020a2

ibeneitez@uoc.edu Correspondence: ibeneitez@uoc.edu (I. Beneitez).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS