Psychoeducational Interventions in Children and Adolescents with Type-1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review

[Las intervenciones psicoeducativas en los menores y adolescentes con diabetes tipo 1: una revisión sistemática]

Bárbara Luque1, 2, Joaquín Villaécija1, 2, Rosario Castillo-Mayén1, 2, Esther Cuadrado1, 2, Sebastián Rubio1, 2, Carmen Tabernero2, 3, and 4

1University of CĂłrdoba, Spain; 2Maimonides Biomedical Research Institute of CĂłrdoba (IMIBIC), Spain; 3Social Psychology Department, University of Salamanca, Spain; 4Institute of Neurosciences of Castilla y LeĂłn (INCYL), University of Salamanca, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2022a4

Received 8 June 2021, Accepted 3 November 2021

Abstract

The effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes is unclear. A systematic review was developed in accordance with PRISMA. Relevant databases (Pubmed, Cochrane, PsycINFO, and PsyARTICLES) were analyzed. Articles of the last decade with type 1 diabetes population between 6 and 18 years participating in psychoeducational interventions were the inclusion criteria. Twenty studies were reviewed, and improvements were found in glycosylated hemoglobin, diabetes knowledge, and psychosocial variables. The results support the positive effect of these interventions. The characteristics that seem to be behind the success of these interventions are the design appropriate to the characteristics of the population, the participation of psychologist and educators, the continuity of the program over time, and the use of digital tools and interaction strategies. Further studies need to be carried out and replicated in different groups of children and adolescents.

Resumen

Hay dudas acerca de la efectividad de las intervenciones psicoeducativas en menores y adolescentes con diabetes tipo 1, motivo por el cual se realizó una revisión sistemática de acuerdo con el protocolo PRISMA. Se analizaron distintas bases de datos (Pubmed, Cochrane, PsycINFO y PsyARTICLES) con los siguientes criterios de inclusión: artículos de los últimos diez años, con población con diabetes tipo 1 de edades comprendidas entre los 6 y 18 años que hubieran participado en cualquier intervención psicoeducativa. Se revisaron 20 estudios y los resultados mostraron una mejora en la hemoglobina glicosilada, en el conocimiento de la enfermedad y en algunas variables psicosociales tras estas intervenciones. Las características que parecen estar detrás del éxito de estas intervenciones psicoeducativas son el diseño adecuado a las características de la población, la participación de profesionales de la psicología y de la educación, la continuidad del programa en el tiempo y el uso de herramientas digitales y otras estrategias de interacción. Se destaca la necesidad de realizar más estudios y que sean replicados en diferentes grupos de menores y adolescentes.

Palabras clave

Diabetes tipo 1, Educación, Psicoeducación, Intervenciones, Niños, Adolescentes, Educación del paciente, Revisión sistemáticaKeywords

Diabetes mellitus type 1, Education, Psychoeducation, Interventions, Children, Adolescents, Patient education, Systematic reviewCite this article as: Luque, B., Villaécija, J., Castillo-Mayén, R., Cuadrado, E., Rubio, S., & Tabernero, C. (2022). Psychoeducational Interventions in Children and Adolescents with Type-1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. ClĂnica y Salud, 33(1), 35 - 43. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2022a4

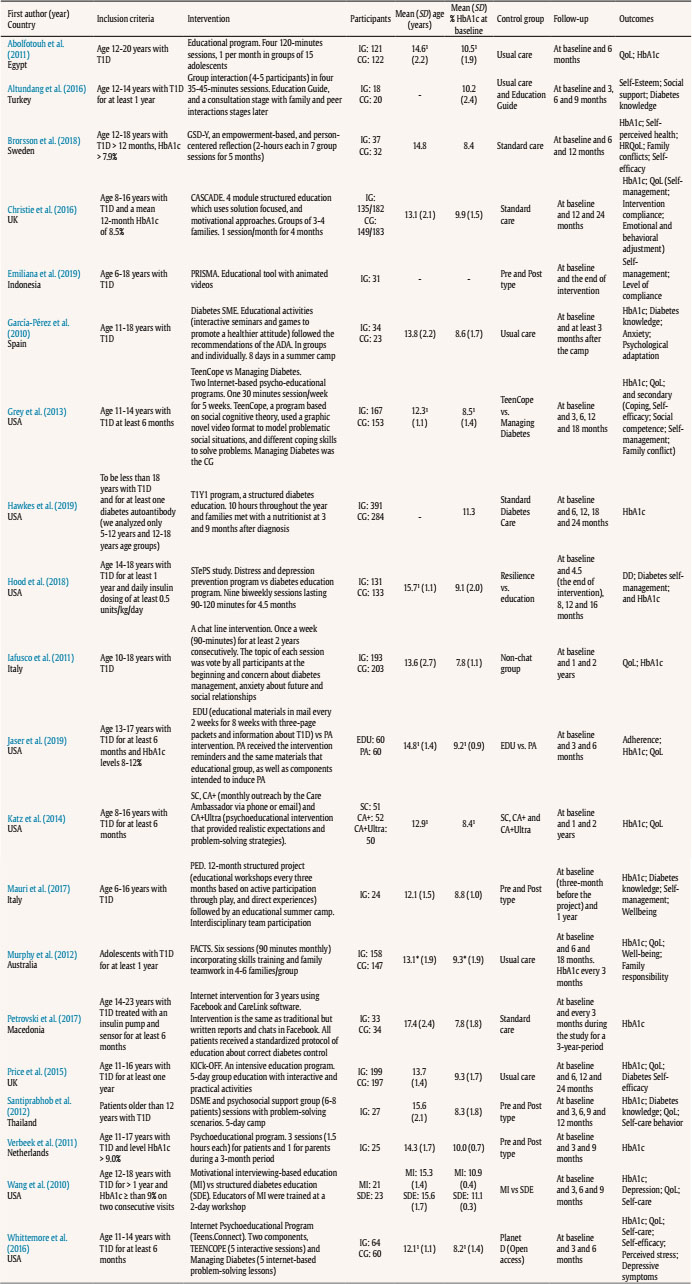

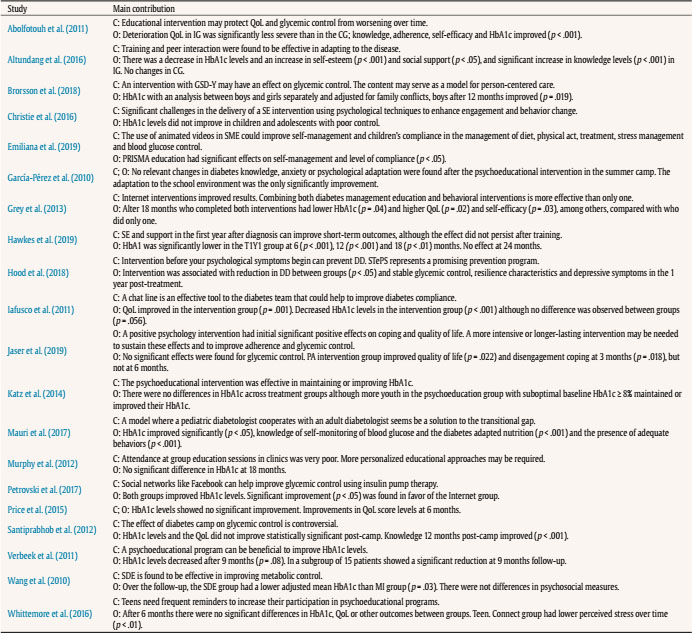

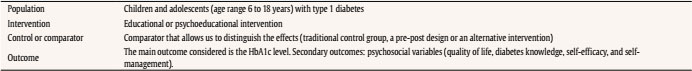

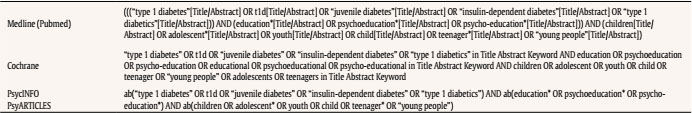

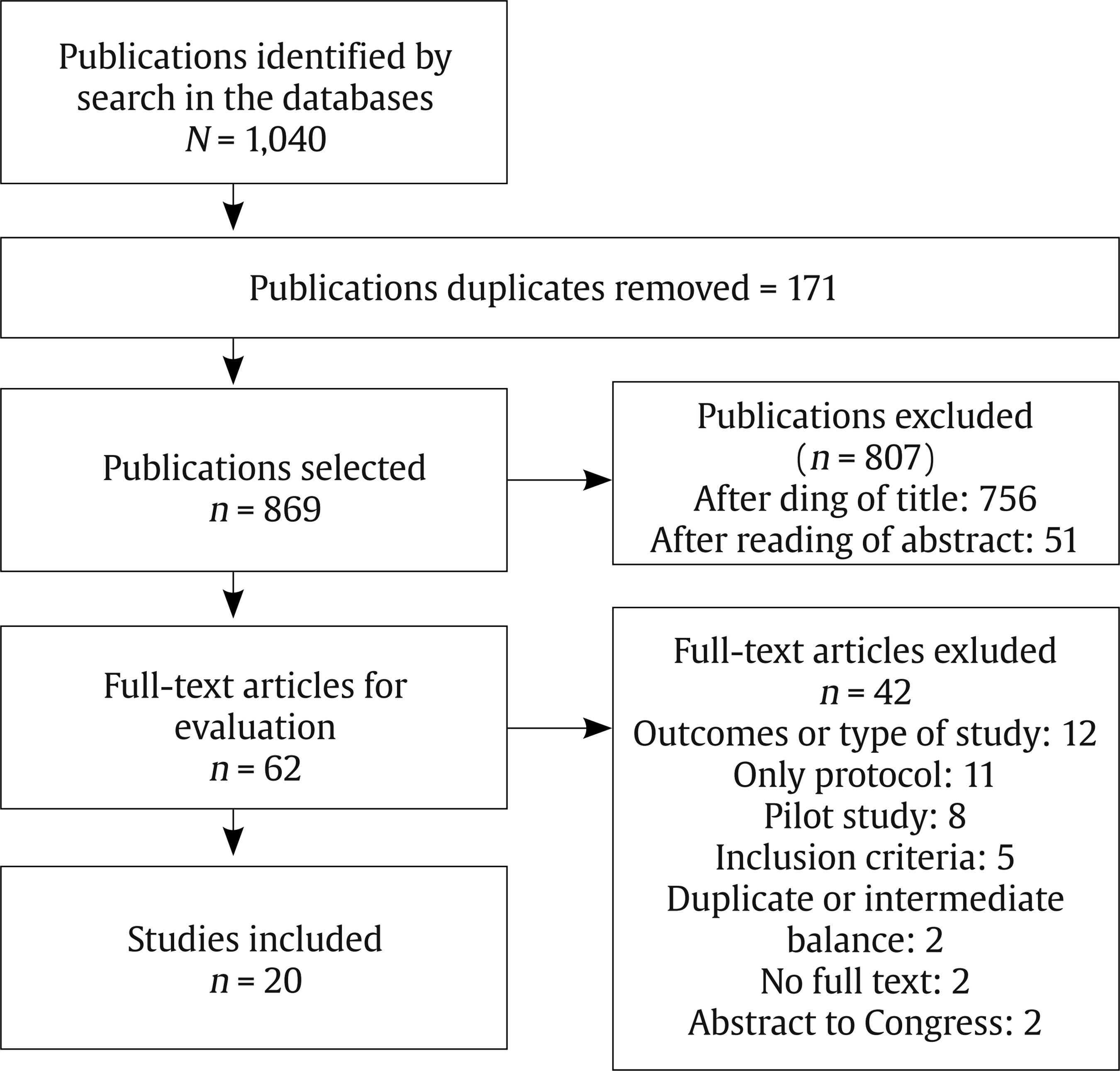

bluque@uco.es Correspondence: bluque@uco.es (B. Luque); carmen.tabernero@usal.es (C. Tabernero)., bluque@uco.es Correspondence: bluque@uco.es (B. Luque); carmen.tabernero@usal.es (C. Tabernero).Chronic diseases are considered as noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and cause many deaths each year. Specifically, 41 million people die each year from these diseases (71% of the deaths that occur worldwide in a year). Diabetes is included in this group of NCDs, along with cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and chronic respiratory diseases (World Health Organization [WHO, 2020]). The main diseases are type 1 diabetes (T1D), type 2 diabetes (T2D), and gestational diabetes. T2D is the predominant type and occurs mostly in adulthood. Although the body can produce insulin, it does not manage it correctly, and its origin is related to a deficit of physical activity and overweight. Gestational diabetes is a temporary condition during pregnancy that could complicate it, produced by an increase in blood glucose levels during this period (WHO, 2021). Finally, T1D, the focus of this study, normally appears at an early age, where the beta cells of the pancreas are attacked, losing its ability to produce insulin, the regulatory hormone of blood glucose levels (Spanish Diabetes Federation [FED, 2020]). Comorbidities of T1D include skin complications, neuropathy, foot problems, eye complications, DKA (ketoacidosis) and ketones, kidney disease, high blood pressure, and stroke (American Diabetes Association [ADA, 2020]). It is estimated that currently 1.1 million children under 19 years of age have T1D worldwide, with 128,900 new cases diagnosed in children each year (International Diabetes Federation [IDF, 2019]). The prevalence differs between countries, although its frequency is increasing, especially in children under 5 years of age. Spain is the country with the highest incidence in southern Europe, with between 1,200 and 1,500 new cases diagnosed each year (Spanish Society of Pediatric Endocrinology [SSPE, 2019]). The worrying data of this disease forces us to explore the scope of action that we have from education and psychology. The WHO has developed the Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013-2020, where the education and empowerment of these patients has a fundamental role (WHO, 2013). In this sense, an educational intervention on diabetes, or diabetes self-management education (DSME), is a teaching-learning process about knowledge, tools, and practices for diabetes self-care that address the needs of the patient, to promote better health (Beck et al., 2017). These conventional educational programs are sometimes supplemented by psychosocial elements such as problem-solving, motivation, coping skills, stress management, counselling, communication skills, and behavioral therapy (Charalampopoulos et al., 2017; Murphy et al., 2006). These are known as psychoeducational interventions. In practice, both interventions are usually combined (Murphy et al., 2006). However, the studies published on the effectiveness of educational or psychoeducational interventions in T1D show contradictory results. On the one hand, there is not enough evidence to justify that these programs are effective by themselves in children and young people with T1D, although there is evidence of their effectiveness when accompanied by other programs (Charalampopoulos et al., 2017; Murphy et al., 2006). On the other hand, positive results such as psychological, and educational benefits are found (Armour et al., 2005; Winkley et al., 2006), achieving better control of the disease and, consequently, a better quality of life for these patients. In addition, we cannot forget signs such as the benefit of the participation of psychologists, the rapid implementation in newly diagnosed children and the innovative strategies aimed at promoting patient participation (Charalampopoulos et al., 2017). Also, education appears to be most effective when integrated into routine care, when it encourages parental involvement and when adolescent self-efficacy (understood as the beliefs in one’s own capabilities to achieve a goal in each situation) is promoted (Murphy et al., 2006; Wood & Bandura, 1989). Early interdisciplinary healthcare enhances the efficiency of disease management, and therefore, the quality of life of these patients (Urzeal et al., 2020). In adult population, which could serve as a background for another population group, one of the highlights is the use of mobile device App that could strengthen the perception of self-care by contributing to an increase in the information available about health education in diabetes, helping patients to control their glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) (Bonoto et al., 2017). The poor adaptation to the disease in the pediatric population (Bilbao-Cercós et al., 2014), understood as the degree of psychosocial adequacy of the subject’s behavior, emotional state, and appraisal in relation to the disease (Portilla del Cañal & Jo, 1995), together with the scarce scientific literature on the characteristics of educational and psychoeducational interventions in this population and the lack of an effective consolidated model, make it necessary to undertake this review to optimize the use of these interventions in children and adolescents with T1D in order to begin adaptation to the disease as soon as possible, since 90% of new diagnoses occur at this age (SSPE, 2019). With this approach, the main aim of this study was to carry out an exploration on the approach of educational and psychoeducational interventions in children and adolescents (age range 6-18 years) with T1D, with two specific objectives: 1) to identify scientific evidence on the effectiveness of these interventions in this population and 2) to consider the methodological and educational strategies used in previous research to extract successful guidelines for designing future interventions. Study Design Published scientific articles have been used to prepare the systematic review; therefore, ethical committee approval has not been necessary. The study design was prepared in accordance with preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009), as well as the instructions suggested by Cajal et al. (2020). To check the effectiveness of the interventions, we collected the psychosocial variables studied and, the HbA1c level as a biomedical indicator. Inclusion Criteria Scientific articles published in English or Spanish were searched, given that English is the language of scientific communication and Spanish is researchers’ native language. To focus on current science and the latest educational trends, such as the use of technology and the rise of mHealth tools for self-care, only papers published during the last ten years (2010-2019) were used. Articles that did not allow access to the full text were eliminated. The country where the intervention was carried out was not considered as a reason for exclusion. We defined the technical inclusion criteria by answering the PICO (acronym for patient, intervention, comparison and outcome) question, as shown in Table 1. Studies that did not differentiate between type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus populations have been excluded. Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria The initial search was performed between October 2019 and February 2020. Four databases were used: Medline (PubMed), Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PsycINFO, and PsyARTICLES. A search was also carried out in May 2020, before the final writing of the paper, to incorporate new studies published in this period. The study population ranged between 6 and 18 years old. Studies were included if the mean age did not exceed 18 years old. Based on our PICO question, a combination of MESH terms (medical subject headings) was used: 1) “type 1 diabetes mellitus”, “juvenile diabetes”, “insulin-dependent diabetes”, “type 1 diabetics”; 2) “education*”, “psychoeducation*”, “psycho-education*”; and 3) “children”, “adolescent*”, “youth”, “child”, “teenager*”, “young people”. These terms and their respective variants are used to search in title, abstract or keywords with the Boolean operators OR and AND, as shown in the detailed search in Table 2. Strategies for the Selection of Studies and Analysis of the Results The selection of articles was made independently by two researchers, and a third resolved any disagreements. Firstly, all publications found within the search criteria were transferred to the free version of the EndNote Clarivate Analytics platform and all the repeat publications were removed. A manual review was then necessary because some references did not match. The selection was first made by reading the title, then by reading the abstracts, and finally by selecting the studies to read in full. Study Selection A total of 1,040 potential scientific publications resulted from the designed search strategy: Medline (n = 598), Cochrane (n = 329), PsycINFO (n = 107), and PsyARTICLES (n = 6), although there were 869 final documents when duplicates were removed. Of these publications, 756 were excluded after the reading of title and 51 after the reading of abstract due to not meeting the inclusion criteria. In this way, 62 studies were selected to be read in full, of which only 20 were analyzed. The rest were discarded for the following justified reasons: other outcomes or type of study (n = 12), only the protocol was published (n = 11), pilot study (n = 8), invalid for inclusion criteria (n = 5), studies duplicated or intermediate balance (n = 2), no full text found (n = 2), or abstract of Congress type (n = 2). All the selected studies met the quality criteria evaluated using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assesstment Tool (Thomas et al., 2004). Figure 1 shows the flow diagram designed by PRISMA to analyze the different stages of study selection. Characteristics of Selected Studies Papers are summarized in Table 3. All studies included were published over the last decade (2010-2019), although some of them were developed in the years prior to the date of their publication; 75% of the studies were clinical trials. There were also cohort studies (10%), quasi-experimental studies (10%), and other not clearly specified (5%). Table 3 Characteristics of Included Trials   Note. ADA = American Diabetes Association; CA = Care Ambassador; CA+ = Care Ambassador Plus; CA+Ultra = Care Ambassador Ultra; CASCADE = Child and Adolescent Structured Competencies Approach to Diabetes Education; CG = control group; DD = diabetes distress; DSME = Diabetes Self-Management Education; EDU = Education; FACTS = Families and Adolescents Communication and Teamwork Study diabetes education program; GSD-Y = Guided Self-Determination-Young; HbA1c = glycosylated hemoglobin; HRQoL = health-related quality of life; IG = intervention group; KICk-OFF = Kids in Control of Food; MI = Motivational Interviewing-based education; PA = positive affect; QoL = quality of life; PED = Pediatric Education for Diabetes; SC = Standard Care; SDE = Structured Diabetes Education; SE = Structured Education; SME = Self-Management Education; STePS = Supporting Teens Problem Solving; T1D = type 1 diabetes; T1Y1 = Type 1 Year 1 program. Studies from many locations resulted: Europe (n = 9), America (n = 7), Asia (n = 2), Africa (n = 1), and Oceania (n = 1). All studies selected involved a children or adolescents population with T1D. The sum of all studies results in 3,743 participants (53.52% females), of which 2,115 belonged to experimental groups with some type of educational or psychoeducational intervention. Study participants range from 24 to 675, and the mean of participants 187.2. The mean age groups ranged from 12.1 ± 1.1 years to 17.4 ± 2.4 years. Thirteen trials recruited adolescents (only over 11 years), while seven studies combined the child-youth population. HbA1c levels at baseline ranged from 7.8 ± 1.1% to 10.9 ± 0.4%. For both age and HbA1c levels, we always prioritized having the mean at baseline, differentiating the group that performed the intervention and the control group, when this data is available. Other data are specified in the general characteristics Table 3. Outcomes Found to Check the Effectiveness of the Intervention The HbA1c level is the most used outcome to evaluate the impact of the educational or psychoeducational intervention; overall, 18 of the 20 selected studies used this variable, which was measured at baseline and at different times during and/or after the intervention. Among the psychosocial variables, the most studied was quality of life or health-related quality of life, which appeared in 12 studies, followed by self-management (n = 5), knowledge of diabetes (n = 4), and self-efficacy (n = 4). Effectiveness of Interventions and Instruments Used Of the 18 studies that measured HbA1c levels in their research, 11 provided significant improvements in this glycemic control variable. This improvement did not occur with the same analyses but can be classified into three groups: produced after comparison with the levels of the experimental group itself prior to the study (n = 3), due to a comparison between the experimental group and the control group (n = 5), or some other improvement due to the interaction of another biomedical or psychosocial variable (n = 3). Regarding psychosocial variables, positive effects were also found: the quality of life measure showed improvements in 5 studies, diabetes knowledge showed improvement in all trials in which it is used (n = 4), self-efficacy in 2 studies, and self-management in 1. In addition, other less-used variables also showed improvements, such as self-esteem, social support, distress diseases, or perceived stress. For the measurement of psychosocial variables included in our study, where improvements were found, the instruments used are described. For the quality of life, the Diabetes Quality of Life for Youth Inventory (DQOLY) (Iafusco et al., 2011), with a Cronbach alpha for its three factors of .85 in life satisfaction, .83 in disease impact, and .82 in disease-related worries in the original questionnaire (Ingersoll & Marrero, 1991). In the Arabic version of DQOLY (Abolfotouh et al., 2011), Cronbach alpha was .83; in the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) (Grey et al., 2013), Cronbach alpha was .87 in the studied sample; in the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Type 1 Diabetes Module (PedsQL-D) (Jaser et al., 2019; Price et al., 2016), Cronbach alpha was .71 in the original scale (Varni et al., 2003); and in the Generic Quality of Life (PedsQL-G) (Price et al., 2016), Cronbach alpha was .88 in the original (Varni et al., 2001). For diabetes knowledge, a test was created by the researchers in one study (Altundag & Bayat, 2016); a questionnaire based on a Spanish adult population was adapted for children and adolescents (García-Pérez et al., 2010), with a Cronbach alpha of .63, and .87 in the original (DISK) (Bueno et al., 1993); some questions were used from the Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire [Questionario sulla conoscenza del diabetes] from the Italian Diabetes Education Study Group (GISED), with a Cronbach alpha of .60; and another non-specific instrument (Santiprabhob et al., 2012). For self-efficacy, a diabetes-specific subscale of self-efficacy for the Diabetes Scale was used, and Cronbach alpha was .88 in the studied sample (Grey et al., 2013). A questionnaire was designed (Abolfotouh et al., 2011), similar to the design by McCaul et al. (1987). For self-management, a self-management questionnaire was used with a reliability test of .91 (Emiliana et al, 2019). General Features of the Intervention All the studies selected according to the inclusion criteria had a methodological design that allowed to measure the effects of the educational or psychoeducational intervention. Three methods were found: intervention group versus control group (n = 13), pre- and post-type (n = 4), and comparison between different interventions (n = 3); 85% of the studies included psychosocial variables to control the effectiveness of the interventions, while the rest (15%) took the biomedical variable HbA1c as the only outcome. The educational perspective shows a heterogeneous implementation of multiple strategies and resources for the development of these interventions. Programs range from a more traditional model of diabetes education to more innovative models that work on psychosocial variables. The involvement of information and communication technologies should be noted: chat line (Iafusco et al., 2011), Facebook (Petrovski & Zivkovic, 2017), animated videos (Emiliana et al., 2019), or other forms of Internet intervention (Grey et al., 2013; Whittemore et al., 2016). Even so, most interventions (75%) did not make use of digital resources: 4 of the 5 studies that rely on digital resources to carry out their interventions showed significant improvements in HbA1c levels. Various psychoeducational strategies were explicitly found: empowerment-based (Brorsson et al., 2019), motivational approaches (Christie et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2010), distress program (Hood et al., 2018), positive affect (PA) (Jaser et al., 2019), role-playing (Grey et a., 2013; Katz et al., 2014; Mauri et al., 2017; Price et al., 2016; Santiprabhob et al., 2012; Whittmore et al., 2016). Six studies were found in which psychologists participated in different ways: in the intervention (García-Pérez et al., 2010; Iafusco et al., 2011; Mauri et al., 2017; Santiprabhob et al., 2012), in a pilot study before intervention (Christie et al., 2016), and training diabetes educator (Wang et al., 2010). All the details of the methods are described in the Interventioncolumn of Table 3, where specific characteristics of the programs are outlined. Regarding the main contributions made by each study and their most outstanding results, they are presented in Table 4. Table 4 Main Contributions of the Studies Analyzed: Conclusions and Outcomes   Note. C = conclusions; CG = control group; DD = diabetes distress; GSD-Y = Guided Self-Determination-Young; HbA1c = glycosylated hemoglobin; IG = intervention group; MI = Motivational Interviewing-based education; O = outcomes; PA = positive affect; QoL = quality of life; SDE = Structured Diabetes Education; SE = Structured Education; SME = Self-Management Education; STePS = Supporting Teens Problem Solving; T1Y1 = Type 1 Year program. The aim of this systematic review was to carry out an exploration to find scientific evidence of the positive impact of educational or psychoeducational interventions, and the strategies used for its development to improve disease control in children and adolescents with T1D. HbA1c levels were the most common outcome measure. Although the improvement of HbA1c level is important, from an education and psychology viewpoint other motivational and psychosocial variables that allow us to achieve greater control of the disease are also relevant. Perhaps, the most important is self-management, the goal of any educational intervention on diabetes. Contrasting Positions on the Effectiveness of Educational or Psychoeducational Interventions There is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of specific psychoeducational interventions for children and adolescents with T1D, based on a review of UK trials (Charalampopoulos et al, 2017). Even so, as this same study confesses, meta-analyses in the USA found that psychoeducational interventions can improve HbA1c levels by up to half a percentage point, in addition to other psychological and educational benefits (Armour et al, 2005; Winkley et al., 2006). Another study argues that although no evidence of significant improvements in HbA1c levels was found in their meta-analysis for the adolescent population after structured education, there was evidence for the adult population (Liu et al., 2020), though a reduction in vascular complications was found in the adult population with T1D (Menezes et al., 2016). The need to continue studying theoretical approaches and methods that can be applied, including the strategies of these programs , remains latent, since education can lead to better control of diabetes (Jenhani et al., 2005; Pals et al., 2020). If one method is effective for one population, could it be effective for another one if it is adapted appropriately? The heterogeneity of the interventions makes it impossible for us to adopt a single stance because of diverse implementations. Strategies, methods, and tools have worked to provide indications that could be addressed and combined in future interventions. Featured Strategies, Methods, and Tools Firstly, the use of digital tools seems to favor the positive effect. Of the five analyzed studies that are supported by digital resources and tools, all five present a significant improvement in some of their analyzed variables: HbA1c levels (Grey et al., 2013; Iafusco et al., 2011; Petrovski & Zivkovic, 2017), self-management (Emiliana et al., 2019), self-efficacy (Grey et al., 2013), and quality of life (Grey et al., 2013; Iafusco et al., 2011). Specifically, animated videos could improve self-management of the disease (Emiliana et al., 2019); internet interventions combining diabetes management education and behavioral interventions (Grey et al, 2013); a chat line (Iafusco et al., 2011); and the use of social networks as a platform to deliver these interventions to improve glycemic control using insulin pump therapy (Petrovski & Zivkovic, 2017). The use of information and communication technology (ICT) creates expectations, yet to be discovered, with great potential for the treatment of chronic diseases such as diabetes (Rhee et al., 2020). This strengthens the idea that using applications could help improve HbA1c control and strengthen the perception of self-care and safety in diabetic patients (Bonoto et al., 2017). Although the use of video games is also recommended as a potential tool for educational interventions, it needs to be specifically designed for that age group and framed within the theoretical foundations of health psychology (DeShazo et al., 2010). In this sense, the use of these tools could facilitate an intervention based on behavioral models to promote the development of self-efficacy judgements in this population, according to the social cognitive theory formulated by Bandura (1997). On the other hand, peer interaction is a strategy that can benefit the achievement of objectives in an educational setting. Specifically, training and peer interaction could be effective in adapting to the disease (Altundag & Bayat, 2016). Peer-based interventions show some promise, although there are not many studies (Kazemi et al., 2016). For the transition stage, the cooperation of an adolescent and an adult, both with diabetes disease, can be an effective option for a progressive transition of care (Mauri et al., 2017). The continuity over time of the interventions also seems to be a key factor in their success. Positive effects have been found with a positive psychology intervention (Jaser et al., 2019), or with a structured education program (Hawkes et al., 2019), but the effects did not continue after training. A more intensive or longer-lasting intervention may be needed to sustain these effects (Jaser et al., 2019). Families who re-visited the web portal after one year obtained better glycemic control (Hanberger et al., 2013). It is probable that young people need frequent reminders to increase their participation in psychoeducational interventions (Whittemore et al., 2016). It is also important to highlight that different methodologies and various approaches achieved positive results with their interventions, e.g., self-management courses (Johnson et al., 2019), structured diabetes education (Wang et al., 2010), psychoeducational programs (Katz et al., 2014; Verbeek et al., 2011), and positive psychology interventions (Jaser et al., 2019), among others. The heterogeneity of the methods used, and their effectiveness, leads us to believe that adaptation to the specific context in which it will be applied is what is truly important (Charalampopoulos et al., 2017), rather than a particular educational program (Murphy et al., 2006). Finally, the implementation of these intervention programs is mostly carried out by medical specialists and nurses in nutrition and diabetes care. Even so, the participation of physicians or multidisciplinary staff has shown effect (Menezes et al., 2016), and the involvement of psychologists was one of the differences with the successful USA programs (Charalampopoulos et al., 2017). We believe that the participation of psychologists is fundamental for successful psychosocial and motivational variables, and the participation of experts in education is fundamental for the pedagogical and methodological approach of interventions where the teaching-learning process has a primary role. Limitations and Future Approaches In accordance with the main aim initially stated, we consider that the development of the research has been correct and has allowed an exploration of the educational and psychoeducational interventions developed in children and adolescents with T1D. In relation to the first specific objective, some of the limitations encountered do not allow us to affirm the effectiveness of these interventions with absolute certainty, although there are indications of their usefulness. In relation to the second aim, techniques and methods have been found that appear to be effective in the development of these interventions. It is possible that some very specific studies have been left out of the selection due to not being included under these criteria. In this way, this study could be extended to other databases, languages, and other criteria to enrich its results. The wide age range chosen could also be a limitation, although due to the limited scientific literature on this topic, we have decided not to adjust it further. In this sense, as research in this field increases, future studies could consider establishing greater differentiation in the stage of the life cycle at which the interventions are targeted taking into account the classification in the stages of human development (e.g., Papalia & Martorell, 2017). Regarding the content, the heterogeneity of the interventions analyzed led us to the decision not to carry out a meta-analysis since there are many variables that could modify an objective result. The main opportunity that it offers us is the possibility of taking the conclusions of the analyzed interventions as a reference, and the successful guidelines discussed, for the design of future interventions. Regarding patients’ age, one of the limitations of the study lies in the fact that the articles reviewed are heterogeneous in terms of the age at which they direct their psychoeducational interventions, therefore the conclusions should be taken with caution. The results obtained and subsequent discussion lead us to believe that educational and psychoeducational interventions have the potential to improve management of the disease and other psychosocial variables in children and adolescents with T1D. We cannot affirm that these interventions are always effective by themselves. It is necessary for more studies to be carried out with a larger population, and that these studies be replicated with the same design in different groups of children and adolescents, considering the characteristics of this population and their interests, to determine their efficacy. In summary, as a basic premise, we believe that an effective intervention must be designed in accordance with the setting and the population in which it is going to be implemented. Even though there is no evidence of a successful valid model, we have found potential indicators that could serve as guidelines for future interventions and further research on them. Psychologists and educators should be involved in the design and supervise these interventions. Professionals trained in to teaching-learning processes, together with specialist medical staff and diabetes educator (generally nurses), create a balance of knowledge and that would allow the continuing study of the effectiveness of these programs. In addition, the correct choice of resources and educational methods depends on the participation of these educators and psychologists. In this regard, there are two issues to consider continuing in the line of research: a resource, digital tools in their different aspects (animated videos, portal web, social networks, Apps, etc.) and a strategy, interaction (peers’ group, people’s experiences, role-play, solving problems, etc.). Both aspects seem that they could facilitate a positive impact on diabetes education and therefore, the control of the disease. Finally, another important factor to consider is the continuity of the programs over time to extend their effectiveness. Funding: This study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and University via a doctoral FPU grant to the second author (FPU18/04504), and was developed while a project was financially supported by the same public organization (PID2019-107304RB-I00), in which the main researchers are co-authors of the paper. Cite this article as: Luque, B., Villaécija, J., Castillo-Mayén, R., Cuadrado, E., Rubio, S., & Tabernero, C. (2022). Psychoeducational interventions in children and adolescents with type-1 diabetes: A systematic review. Clínica y Salud, 33(1), 35-43. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2022a4 References References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis. |

Cite this article as: Luque, B., Villaécija, J., Castillo-Mayén, R., Cuadrado, E., Rubio, S., & Tabernero, C. (2022). Psychoeducational Interventions in Children and Adolescents with Type-1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. ClĂnica y Salud, 33(1), 35 - 43. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2022a4

bluque@uco.es Correspondence: bluque@uco.es (B. Luque); carmen.tabernero@usal.es (C. Tabernero)., bluque@uco.es Correspondence: bluque@uco.es (B. Luque); carmen.tabernero@usal.es (C. Tabernero).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS