Family Functioning in a Portuguese Sample of Adults during COVID-19: Does Hope Matter?

[Funcionamiento familiar en una muestra portuguesa de adultos durante el COVID-19: Âżimporta la esperanza?]

Martim Santos, Ana Ferraz, Ana C. Bernardo, Ana M. Machado, Marta Evangelista, Inês Ribeiro, and M. Graça Pereira

Psychology Research Centre (CIPsi), School of Psychology, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal

https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2023a1

Received 1 April 2022, Accepted 24 October 2022

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to explore the relationships between sociodemographic, clinical, and psychological variables and their contribution towards family functioning during the first wave of COVID-19 in Portugal. The COVID-19 pandemic was an overwhelming and stressful life event with social consequences that impacted family functioning and contributed to multilevel disruptions. The study used a cross-sectional design and included 110 participants (94 women), with a mean age of 35.71 (SD = 13.53). Participants answered self-report measures assessing family satisfaction, hope, psychological well-being, risk perception, and family functioning. Hope (pathways subscale) played a moderating role in the relationship between family satisfaction and family functioning. Family satisfaction and psychological well-being partially mediated the relationship between hope and family functioning. Clinical relevance and implications for further research are addressed. Intervention should focus on increasing psychological well-being and hope together with family satisfaction in order to promote family functioning. For those individuals struggling with COVID-19 issues, mental health interventions are paramount.

Resumen

Este estudio ha tenido como objetivo explorar la relación entre las variables sociodemográficas, clínicas y psicológicas y el funcionamiento familiar en la primera oleada de COVID-19 en Portugal. La pandemia de COVID-19 fue una situación de vida abrumadora y estresante con consecuencias sociales que afectaron en el funcionamiento familiar. El estudio utilizó un diseño transversal e incluyó 110 participantes (94 mujeres), con una edad media de 35.71 años (SD = 13.53). Los participantes respondieron a medidas que evaluaban la satisfacción familiar, la esperanza, el bienestar psicológico, la percepción del riesgo y el funcionamiento familiar. La esperanza (subescala “caminos”) desempeñó un papel moderador en la relación entre la satisfacción familiar y el funcionamiento familiar. La satisfacción familiar y el bienestar psicológico mediaron parcialmente en la relación entre la esperanza y el funcionamiento familiar. Se abordan la importancia clínica y las implicaciones para futuras investigaciones. La intervención deberá centrarse en aumentar el bienestar psicológico y la esperanza junto con la satisfacción familiar para promover el funcionamiento familiar. Para los individuos que luchan con problemas de COVID-19 son primordiales las intervenciones de salud mental.

Palabras clave

COVID-19, Funcionamiento Familiar, SatisfacciĂłn Familiar, Esperanza, Portugal, Bienestar psicolĂłgicoKeywords

COVID-19, Family functioning, Family satisfaction, Hope, Portugal, Psychological well-beingCite this article as: Santos, M., Ferraz, A., Bernardo, A. C., Machado, A. M., Evangelista, M., Ribeiro, I., & Pereira, M. G. (2023). Family Functioning in a Portuguese Sample of Adults during COVID-19: Does Hope Matter?. ClĂnica y Salud, 34(1), 1 - 8. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2023a1

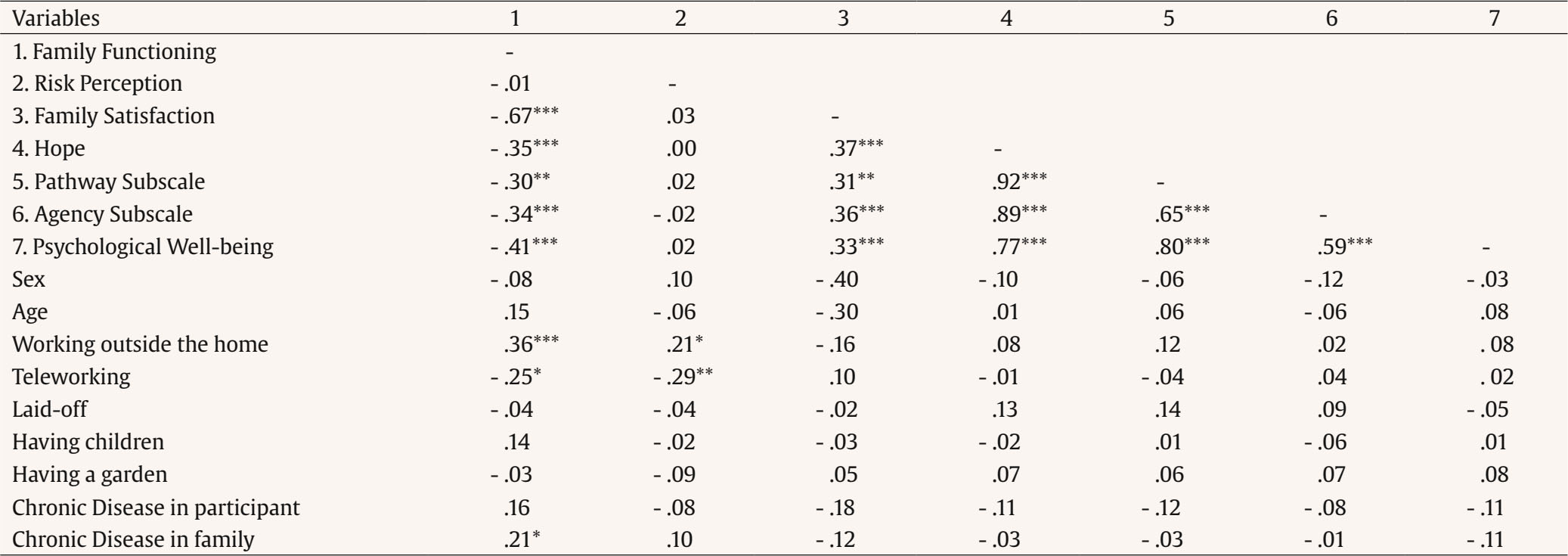

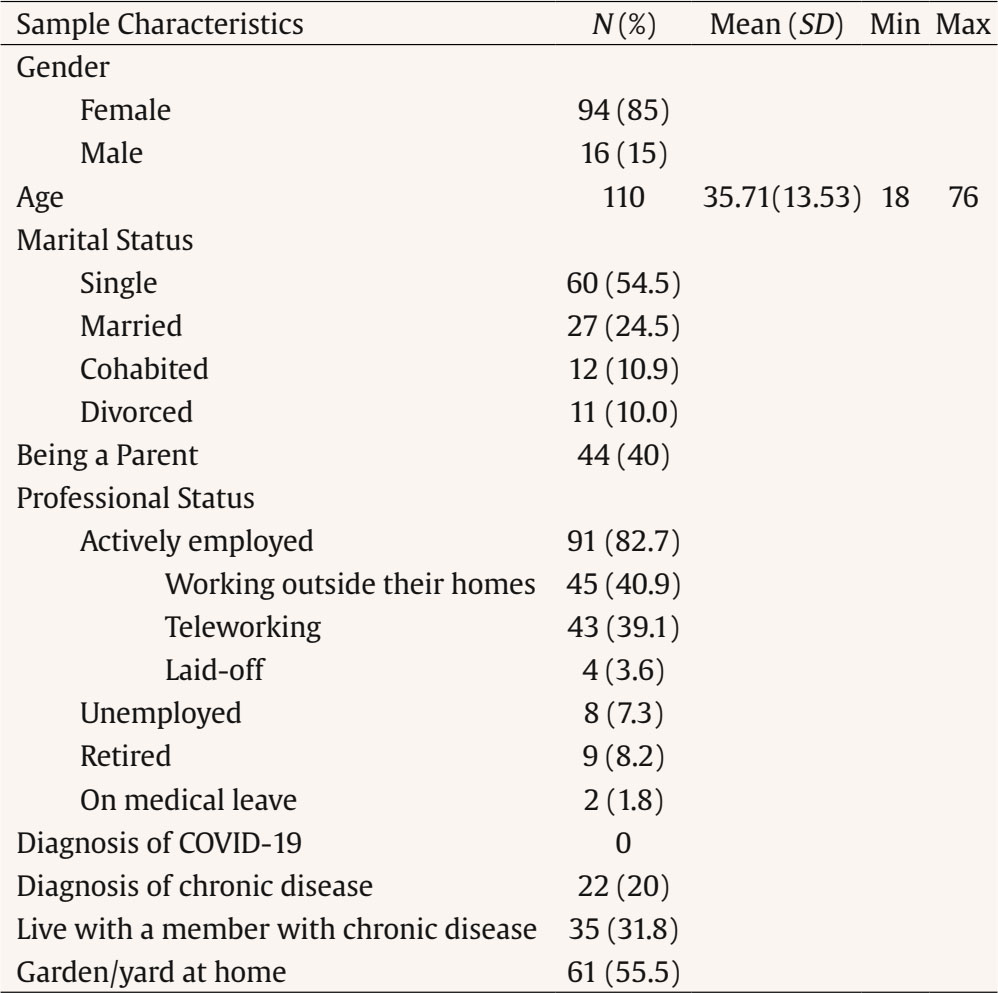

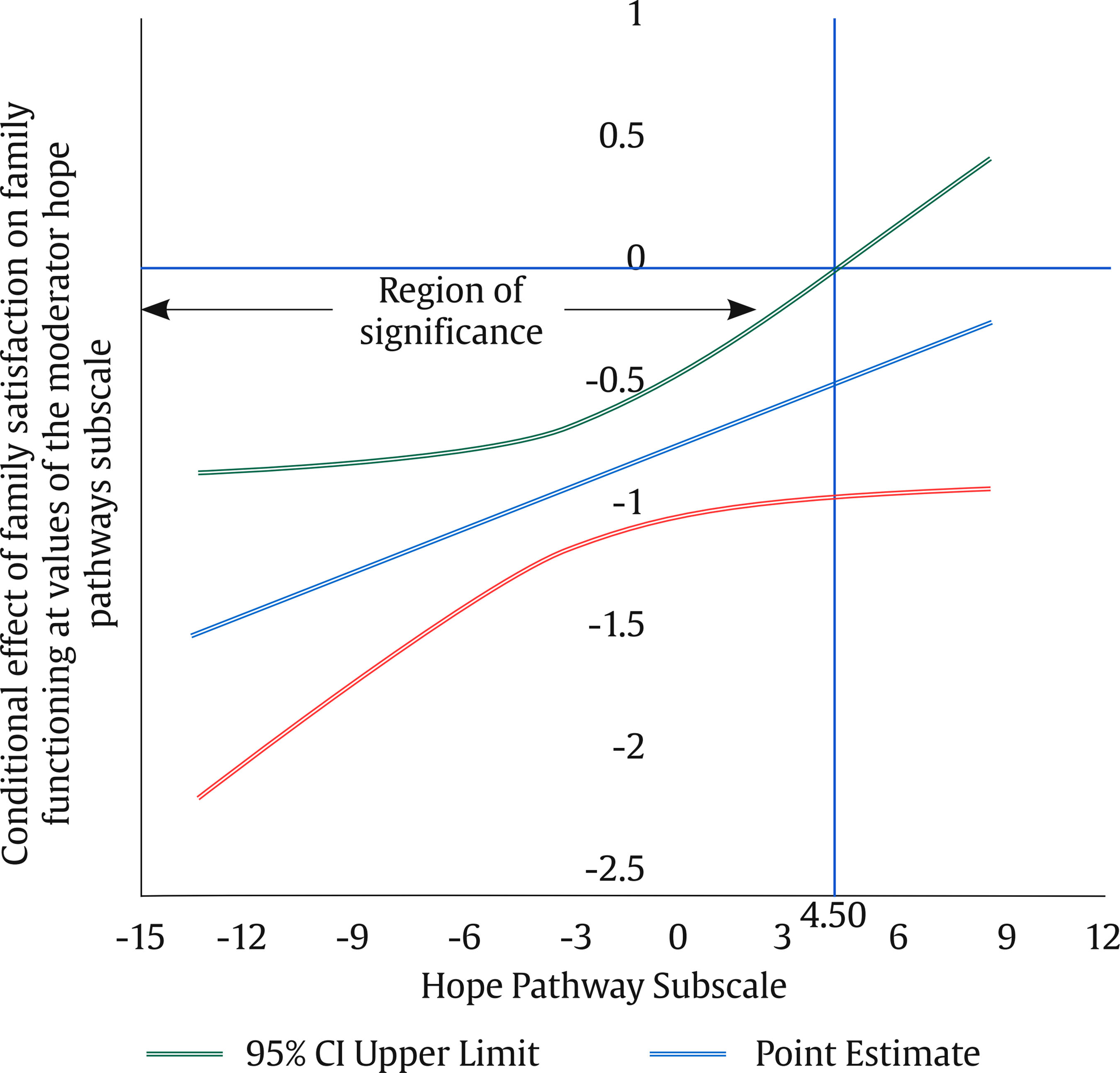

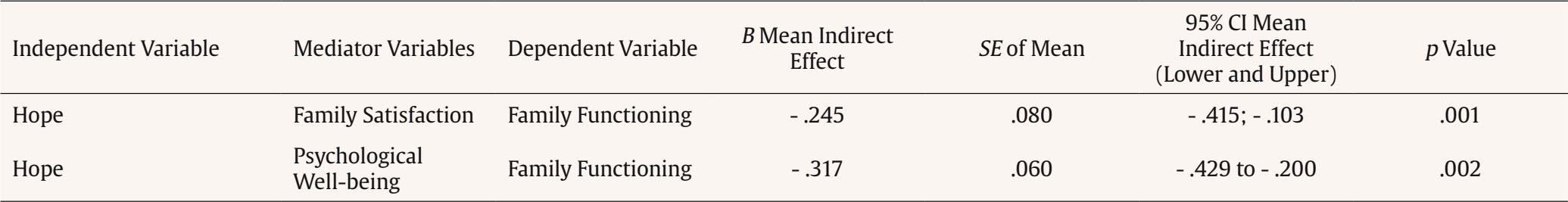

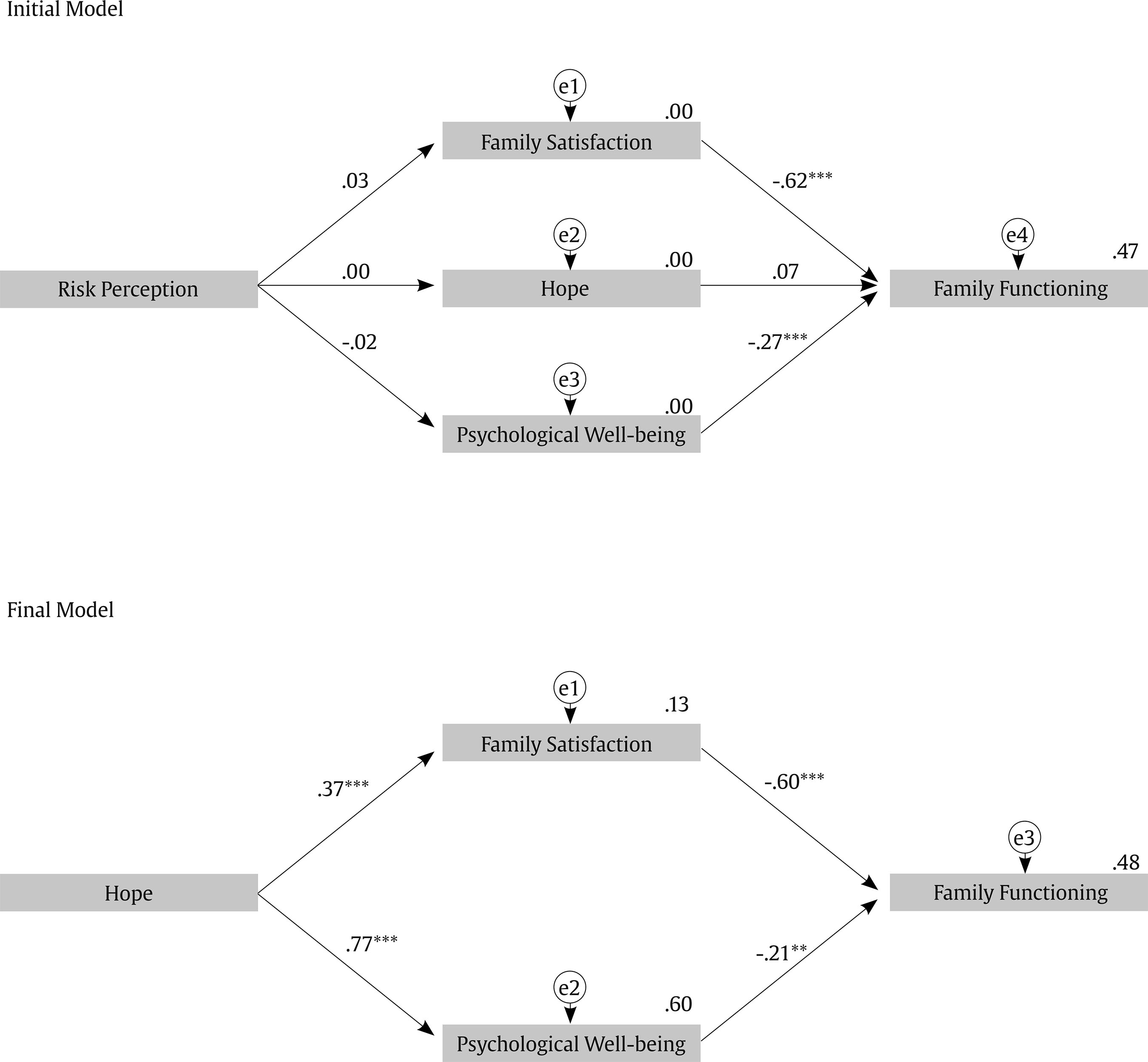

Correspondence: gracep@psi.uminho.pt (M. Graça Pereira).The World Health Organization (WHO) on January 30th 2020 considered COVID-19 as a public health emergency of international concern, and on 11th, March 2020 it was declared as a pandemic (World Health Organization [WHO, 2022a]). On March 2nd 2020, the first cases of COVID-19 were recorded in Portugal (Direçao y Geral da Saúde [General Director of Health], 2020), and nowadays more than 615 million cases of COVID-19 were confirmed. Worldwide, mortality stands above six million and approximately 12 billion vaccine doses have been administered (WHO, 2022b). Physical distancing to reduce the risk of transmission and other guidelines as self-isolation/self-quarantine highlight the multiple challenges of COVID-19 outbreak, particularly at financial (e.g., financial strain, laid-off, job disruption), physical (e.g., clinical symptoms), and social (e.g., social isolation, family management) domains (Chen et al., 2020). In several countries, including Portugal, staying-at-home was imposed, and this period was particularly challenging since it required individuals to change roles and to be more intimate with their family for a longer period combined with higher levels of stress imposed by COVID-19 (Brock & Laifer, 2020). Recent studies suggest that this period was more critical for men, particularly younger, on teleworking, or unemployed, although studies focusing on men are underrepresented in the literature (e.g., Santos et al., 2021). COVID-19 Stress Process and Family Functioning The COVID-19 outbreak had a significant impact on several features of individuals’ lives, particularly on key processes of family dynamics and demands (e.g., Daks et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2020). The current pandemic is considered a family stressor due to the unpredictable and enduring characteristics of COVID-19 that interfere with family dynamics and demands (Brock & Laifer, 2020; Daks et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2020). These multiple challenges associated with COVID-19 can disrupt family functioning (Brock & Laifer, 2020), and compromise family emotional connection, communication, rules, roles, and coping (Olson et al., 2000). In fact, family functioning refers to the social and structural characteristics of the family environment and includes interactions and relationships within the family, particularly levels of conflict and cohesion, adaptability, organization, and quality of communication (Lewandowski et al. 2010). Daks et al. (2020) found that COVID-19 related stressors predicted poorer family functioning, suggesting that stress associated with new family demands (e.g., stay-at-home confinement) predicted higher levels of family strain, impairing the capacity to solve problems, decision-making, and conflict management. Moreover, working from home may decrease work-family conflict, but also enhance the interference of work into daily life (Dockery & Bawa, 2018). However, spending more time with the family may also create opportunities for improved satisfaction with relationships, problem-solving, more intimate personal relationships, and family satisfaction (Günther-Bel et al. 2020). Family satisfaction refers to beneficial attitudes toward one’s family life and perceptions of family quality such as solidarity, happiness, and overall relational well-being (Olson, 2008; Soliz & Kellas, 2014), given that, family satisfaction is a positive predictor of family functioning, since it contributes to the fulfilment and happiness of the family system (Olson, 2000). It is expected that the early stages of a stressor event (i.e., the first wave of the COVID-19) represent one of the most critical phases of the family adaptation process (Brock & Laifer, 2020; Daks et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2020). However, it is not yet known how Portuguese families have adjusted during this phase. There is also evidence that other factors such as living conditions (e.g., having a garden at home) and clinical characteristics (e.g., the presence of chronic diseases in the family) may play a determinant role, particularly during this period (Corley et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020). According to Corley et al. (2021), adults that spent time in the garden presented better mental well-being compared with pre-lockdown. Therefore, home gardens may be a potential health resource for adults and children, improving mental health, because it provides more space for children to play freely, to be in contact with nature, and increases visual exposure and possible contact with neighbours, allowing more social interaction (Corley et al. 2021). Also, the study of Wang et al. (2020) found that the presence of chronic diseases in the family may create additional stressors and have been related to adverse psychological effects in families due to the COVID-19 outbreak. During COVID-19 pandemic, the perception of the event as threatening as well as the risk perception involved were determining factors for an individual’s cooperation regarding adherence to specific health behaviors to avoid the virus spread, such as washing hands often, distancing oneself physically, avoiding public places, and wearing facial masks (Dryhurst et al., 2020). In assessing COVID-19 risk perception in Europe, Asia, and America, Dryhurst et al. (2020) concluded that an individual’s factors, such as direct and indirect experience with the virus, confidence in government measures, science, and health professionals, influence COVID-19 risk perception. Recent studies suggest that risk perception was higher when there was a direct and personal experience with the virus (Dryhurst et al. 2020). Moreover, a study conducted in Portugal during the current pandemic found a positive relationship between risk perception and psychological well-being (Santos et al., 2021). Psychological well-being has been considered by Ryff (1989) as a set of psychological features involved in positive human functioning that included subjective, social, and psychological health-related dimensions. (Keyes et al., 2002). In fact, the pandemic challenges (e.g., stay-at-home confinement) negatively impacted health and well-being (Daks et al., 2020). Nevertheless, when confronting adverse events (e.g., COVID-19), psychological well-being may play a protective role since it is associated with fulfilling one’s potential, having a purpose in life, coping with challenges, and trying to achieve goals (Ryff, 1989). According to Miller et al. (2000) and Skinner et al. (2000), the psychological well-being of family members is positively associated with family functioning. The Role of Hope During stressor events, positive feelings such as hope may play a protective role, reducing the psychological distress (Counted et al., 2022; Ong et al., 2006). Ong et al. (2006) suggested that hope is an important source of resilience and emerges to shape the meaning of life stressors. Additionally, the authors found that hope contributed to adaptive recovery from stress and provided protective gains by maintaining negative emotions low. In fact, hope refers to an individual’s ability to identify pathways to goals and achieve desired outcomes of goal-oriented pursuits (Snyder, 2002). Hope involves a pathway dimension and an agency dimension, with the pathway dimension representing the perception about ones’ ability to generate useful ways to meet goals, whereas the agency dimension includes the perception about ones’ capacity of goal-directed determination (Snyder, 2002). Thus, hopeful thinking during the COVID-19 pandemic might be a valuable strategy that motivates individuals to find effective ways of reaching goals that contribute to well-being (Counted et al., 2022). A recent study found that hope moderates the mediating role of loneliness in the relationship between family functioning and mental health (Pan et al., 2020). However, the moderating role of hope among familiar variables is yet unknown, particularly during stressor events. The current study was conceptually based on the Process Model of Stress and Coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). In the present study, conducted during the first wave of COVID-19 in Portugal, the psychosocial outcome addressed was family functioning. According to the model, when faced with a certain situation considered a threat, the individual initiates a process that involves two phases: primary appraisal and secondary appraisal. The model considers the perceived threats (primary appraisal) related to the stressor and, to cope with stress (secondary appraisal), the influence of internal and external resources. In this study, the stressor was assessed using the COVID-19 risk perception. In turn, internal resources were assessed using hope and psychological well-being and, finally, external resources were evaluated using family satisfaction. The model predicts moderations and mediations among the variables (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Overall, recent studies emphasise the impact triggered by this stressor event on psychological and family functioning (Pan et al., 2020). As Miller et al. (2000) and Skinner et al. (2000) propose, physical and mental health status of family members play an important role in family functioning. Additionally, the impact of COVID-19 on individuals is undeniable, but how individual variables, such as hope, psychological well-being, and risk perception contribute to family functioning in Portuguese individuals during the first wave of COVID-19 is not yet clear. The aim of this study was (a) to analyze the relationships between sociodemographic (e.g., sex, age, working outside the home, teleworking, laid-off, having children, having a garden), clinical (e.g., presence of chronic disease in the family), psychological variables (e.g., hope, psychological well-being, family satisfaction) and family functioning; (b) to evaluate the moderating role of internal resources (e.g., hope) in the relationship between family satisfaction and family functioning; and (c) to test the stress process model taking into consideration the stressor (e.g., risk perception of COVID-19), internal/external resources (e.g., family satisfaction, psychological well-being, hope), and family functioning. We hypothesised that age, teleworking, having a garden, higher family satisfaction, being hopeful, and psychological well-being will be associated with better family functioning. Also, gender (being a man), working outside the home, laid-off, having children, presence of chronic disease in an individual/family member, and more risk perception will be associated with worse family functioning; hope (pathways and agency) will moderate the relationship between family satisfaction and family functioning and that hope, well-being and family satisfaction will have an indirect effect between risk perception and family functioning. Participants Data were collected in Portugal powered by Qualtrics XM and the sample comprised 110 participants (94 women and 16 men). The criteria for participant inclusion were: (a) being a Portuguese resident, (b) being 18 or older, and (c) living/cohabitating in a family context. Participants of the same household were excluded from the sample. Of the total sample, 94 (85%) were female. The mean age was 35.71 (SD = 13.53), ranging from 18 to 76 years old. No participants had been diagnosed with COVID-19. Table 1 describes the sociodemographic characteristics (Table 1). Instruments Sociodemographic and Clinical Questionnaire This questionnaire assesses sociodemographic variables (e.g., sex, age, marital status, professional status, teleworking, laid-off, having children) and clinical variables (e.g., chronic disease in the family, COVID-19 diagnosis). Numerical Risk Perception Scale (Crump, 2010; Portuguese version by Pereira & Pereira, 2013) This scale consists of a single item that measures participants’ perception of the risk of contracting COVID-19 (e.g., “On a scale of 0 to 10 where 0 is none and 10 is the most: how much risk do you perceive of contracting the COVID-19 virus?”). The item is assessed using a visual analogue scale, from 0 to 10, where scores from 0 to 2 correspond to the slightest perception of risk, 3 to 7 indicate a moderate perception of risk, and 7 to 10 consist of an intense perception of risk. Hope Scale (AHS; Snyder et al., 1991; Portuguese Version by Pais-Ribeiro et al., 2006) This questionnaire includes 12 items: 8 items assess hope within two domains (agency and pathways) and 4 are distractors (e.g., “I feel tired most of the time”). The pathways subscale assesses one’s ability to generate plans and strategies for pursuing goals (e.g., “I can think of many ways to get out of a jam”) and the agency subscale assesses the perception regarding one’s capacity for initiating and persisting on actions to pursue important goals (e.g., “I’ve been pretty successful in life”). Items are scored on an 8-point Likert-type scale, ranging from definitely false (1) to definitely true (8), with the highest scores indicating more hope. In the original version, Cronbach’s alpha was between .74 and .84. for the total scale, between .63 and .80 for the agency domain, and between .71 and .76 for the pathway’s domain. In this study, alpha for the agency domain was .67, .87 for the pathway’s domain, and .86 for the total scale. Systemic Clinical Outcome and Routine Evaluation (SCORE-15; Stratton et al., 2010; Portuguese Version by Vilaça et al., 2014) SCORE-15 assesses family perceptions with 15 items, through three dimensions: family strengths (e.g., “We trust each other”), family communication (e.g., “I feel it is risky to disagree in our family”), and family difficulties (e.g., “In my family we seem to have one crisis after another”) scored in a five-point Likert scale, ranging from describe us very well (1) to describe us very badly (5). With inversion of the negative items, higher results indicate worse family functioning. In the original version, Cronbach’s alpha was .84 for the total scale. In the current study, the alpha for the total scale was .88. Family Satisfaction (FSS; Olson, 2008; Portuguese Version by Pereira & Teixeira, 2013) FSS measures family satisfaction through 10 items (e.g., “The family’s ability to resolve conflicts”). Answers range from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5) with higher scores indicating more family satisfaction. In the original version, Cronbach’s alpha was .93. Alpha in the present study was .95. Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWS; Ryff, 1989; Portuguese Version by Novo, 2003) This questionnaire includes 18 items assessing six dimensions: autonomy (e.g., “In many ways I feel disappointed with what I have achieved in life”), environmental mastery (e.g., “I am able to use my time well in order to get everything done that needs to be done”), personal growth (e.g., “I like most aspects of my personality”), positive relations with others (e.g., “I have difficulty organizing my life in such a way that I am satisfied”), purpose in life (e.g., “I tend to worry about what other people and colleagues think of me”), and self-acceptance (e.g., “I don’t really have a sense of what I’m trying to achieve in life”). Items are scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale with higher scores indicating greater psychological well-being. In the original version, Cronbach’s alpha was .85 for the total scale. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was .84. Procedure This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research in Social and Human Sciences (CEICSH) of the University of Minho (Reference Number: CEICSH-018/2021), within an initiative to support scientific research in health psychology and behavior change (Via Verde Special Call) by Portuguese Psychologists Association (OPP). Data was collected through an online survey software: Qualtrics XM. The goals of the study, the inclusion criteria, and the link to access the survey were shared on social networks. On the first page of the questionnaire, the informed consent form was included. The survey took approximately 15 minutes to answer. Data collection started on May 21st, 2020 until November 16th, where the population was under some limitations and restrictions, corresponding to the first wave of COVID-19. Until May, 2020 the individuals were under stay-at-home confinement, although the teleworking and some other restrictions continued over the time. Data Analysis To test the relationships between the sociodemographic, clinical, and psychological variables, the Pearson correlation coefficient was used. To perform the moderator role of hope (pathways subscale) in the relationship between family satisfaction and family functioning, the moderation assumptions were tested with the Macro Process for SPSS, version 3.5, and the Johnson-Neyman (JN) technique since all the assumptions were fulfilled. JN technique allowed us to determine the transition point in which hope was enough to detect a difference in the relationship between family satisfaction and family functioning (p < .05) (Johnson & Fay, 1950). Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS ® (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 27.0. A path analysis was performed based on the stress process model using the IBM statistics package SPSS AMOS (27.0 version). To assess the adequacy of the model fit, the chi-square test (χ2), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the root mean square error approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root means square residual (SRMR) were used (T. Brown, 2006) together with the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) (Ferron et al., 2008). Relationship between Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Psychological Variables The results showed positive moderate correlations between hope and its subscales with family satisfaction, and negative moderate correlations with family functioning. Positive large correlations were found between hope and its subscales and psychological well-being. Thus, being more hopeful, having a higher perception about one’s ability to generate the plans and strategies for pursuing goals (hope pathways subscale), and having a higher perception regarding one’s capacity for initiating and persisting on actions to pursue important goals (hope agency subscale) was associated with more family satisfaction, greater psychological well-being, and better family functioning. Negative and positive moderate correlations were also found between psychological well-being, working outside the home and family functioning, respectively. A negative large correlation was found between family satisfaction and family functioning, while negative and positive small correlations were found between teleworking and the presence of chronic disease in the family with family functioning, respectively. Thus, less family satisfaction, lower psychological well-being, working outside the home, no teleworking, and the presence of chronic disease in the family were associated with worse family functioning (Table 2). Table 2 Correlation between Sociodemographic Variables and Psychological Variables (N = 110)   *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Hope (Pathways and Agency Subscales) as a Moderator between Family Satisfaction and Family Functioning The model that tested the moderating role of the hope pathways subscale in the relationship family satisfaction and family functioning was significant, F(3, 106) = 34.1431, p < .001, β = .0562, 95% CI [.0002, .1121], t = 1.9897, p = .0492, explaining 51.62% of the variance. Thus, there was a negative relationship between family satisfaction and family functioning when hope pathways subscale was both high (β = -.9489, 95% CI [-1.2135, -.6843], t = -7.1091, p = .0000) and low (β = -.4597, 95% CI [-.9040, -.0155], t = -2.0516, p = .0427), but more intense in the latter situation. The Johnson-Neyman (JN) technique showed that family satisfaction was significantly correlated with family functioning when the standardized value of hope (pathway subscale) was 4.5046 above the mean (β = -.4515, p = .0500), and this was true for 85.45% of the sample (Figure 1). Hope (agency subscale) did not moderate the relationship between family satisfaction and family functioning, F(3, 106) = 21.8205, p < .001, β = .0315, 95% CI [-.0197, .0826], t = 1.2186, p = .2257 (Figure 1). Path Analysis Model The results of the path analysis showed that the adjustment statistics for the initial model were χ2 = 115.299(4) = 28.825, TLI = - .558, CFI = .377, RMSEA = .505, and SRMR = .264, with AIC = 137.299 and BIC = 167.005. The adjusted final model indicated a good fit, χ2 = 1.279(2) = .640, TLI = 1.012, CFI = 1.000, RMSEA = .000 and SRMR = .021, with AIC = 17.279 and BIC = 38.883. The indirect effect of hope on family functioning was partially mediated by family satisfaction (mediation effect = -.245, 95% confidence interval = -.414 to -.103, p < .01) and by psychological well-being (mediation effect = -.317; 95% confidence interval = -.429 to -.200, p < .01). Figure 2 shows the initial and final model (Table 3, Figure 2). Regarding the first goal, the results showed that working outside the home was associated with poorer family functioning and, in sharp contrast, teleworking was associated with better family functioning. These findings are interesting and may have to do with being at home and having the opportunity to spend more time with the family, during the pandemic, which may be perceived as a chance to have more intimate personal relationships and improve problem-solving (Günther-Bel et al. 2020). Furthermore, teleworking is associated with less decrease work-family conflict (Dockery & Bawa, 2018). The presence of chronic disease in the family was associated with poorer family functioning, which is consistent with previous studies (Wang et al., 2020), that showed that chronic disease is related to adverse psychological effects in families. In fact, chronic disease may cause significantly prolonged unbalances for families, particularly in this pandemic period, where families have to deal with several new daily challenges regarding the care of the family member with chronic disease (e.g., accessing medical care). Additionally, unlike other studies, having a garden was not associated with family functioning. A study from Corley et al. (2021) with older adults found an association between spending time in the garden and well-being, suggesting that individuals that spend more time in the garden during lockdown had better self-reported physical health and emotional/mental well-being, compared with pre-lockdown. According to the author, having a garden or a balcony allows people to have more activities being associated with improved mental health, and suggesting that a garden is a potential health resource during COVID-19 lockdown (Corley et al. 2021). In the current study, the questionnaire only evaluated the existence of a garden, and not if the family spent time in the garden, which may have conditioned the relationship between the variables. Furthermore, contrary to our expectations, sex, age, and laid-off were not associated with family functioning. Although it is known from previous research that the risk of severe manifestations and mortality increases with age, being more prevalent in men (Chen et al., 2020), the current sample consisted mostly of women with an average age of 35 which might explain the absence of associations. The same holds for laid-off considered one of the COVID-19 challenges that could affect an individual’s mental health, with an impact on family functioning (Pan et al., 2020), since the sample was composed mostly of individuals who were active workers. Interestingly, in this study, having children was not associated with family functioning. COVID-19 lockdown demand measures may lead to daily disturbances in family functioning due to the increased difficulties with managing their children’s problems and/or children’s academic life (Brown et al., 2020). Also, the lockdown was experienced as more difficult by those with younger children and those with children with increased emotional and behavioral problems (Spinelli et al., 2020). However, some parents reported that lockdown may also offer opportunities to spend more time together (Brown et al., 2020). One explanation for the non-correlation may be the low percentage of participants with young children up to five years old (11.8%) in the present sample. Additionally, being hopeful, particularly being more perceptive about one’s ability to plan to meet goals (pathways), and more perceptive about one’s capacity of goal-directed determination (agency) were associated with more family satisfaction, greater psychological well-being, and better family functioning. The literature has shown that hope is an important variable with a protective role in stressor events (Counted et al., 2022) and it refers to an individual’s ability to identify pathways to goals and to achieve desired outcomes of goal-oriented pursuits (Snyder, 2002). Counted et al. (2022) found that hope had a positive effect on well-being during COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, hopeful thinking might be a valuable strategy that motivates individuals to find effective ways of reaching goals that contribute to well-being (Counted et al., 2022), particularly with COVID-19 demands. Hope was also associated with family satisfaction and family functioning, emphasizing its importance within the family context, particularly in a sample of Portuguese adults, since hope develops in a supportive family environment (Snyder, 2002). Actually, individuals are more likely to feel support and security when cooperating with others and receiving help from others when hope is high (Fang & Sun, 2018). Hence, the current results suggest that Portuguese adults who identify pathways to goals and/or have the ability to achieve desired outcomes of goal-oriented pursuits are more likely to feel happy and fulfilled with each member of the family and fewer family difficulties. Also, family satisfaction was associated with better family functioning, which is in line with Olson (2000). In fact, families with good communication function better, being able to be close to each other and cope with problems (Olson, 2000). Overall, family satisfaction is a key contributor to family functioning, as it evaluates the degree to which family members feel happy and fulfilled with each other (Olson, 2000). Contrary to our expectations, risk perception was not associated with family functioning. In fact, the literature shows that there is a positive relationship between risk perception and psychological well-being (Santos et al., 2021). Moreover, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a perception of high risk when one has a personal experience with the virus (Dryhurst et al. 2020). In this study, no participant was diagnosed or directly experienced the virus in the family context, so the perception of risk may not have been significant. Greater psychological well-being was associated with higher family satisfaction and better family functioning, which is consistent with Miller et al. (2000) and Skinner et al. (2000). Psychological well-being is related to fulfilling one’s potential, having a purpose in life, coping with challenges, and trying to achieve goals (Ryff, 1989). Therefore, this is directly associated with better communication, cohesion, and adaptability between family members. Regarding the moderating role of internal resources (hope subscales) in the relationship between family satisfaction and family functioning, results showed only significant effects for hope pathways. This result is in line with the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), which expresses the role of internal resources (e.g., hope) between external resources (e.g., family satisfaction) and the outcome (e.g., family functioning). Since hope pathways assess one’s capacity to generate effective plans to reach one’s goals (Pais-Ribeiro et al., 2006), a low perception about this capacity may lead to a negative evaluation of the degree to which family members feel happy and fulfilled with each other (Fang & Sun, 2018; Snyder, 2002) with an impact on family functioning. In this study, it seems that individuals with lower levels of hope (pathways subscale) were those who experienced a higher impact of family satisfaction on family functioning. Concerning the non-moderating role of the hope agency subscale, it seems that participants gave more emphasis to one’s ability to generate plans and strategies for pursuing goals. The final model, with family satisfaction and psychological well-being having a partial indirect effect between hope and family functioning, is supported by the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The final model shows a good adjustment in individuals with no diagnosis of COVID-19 and revealed that risk perception was not a significant variable in the model. Indeed, hopeful individuals are more likely to be satisfied with family (Fang & Sun, 2018; Snyder, 2002), which leads to fewer difficulties and adaptive coping strategies (Olson, 2000) Also, adults with higher hope tended to recover from stressful situations positively overcoming their negative thoughts (Fang & Sun, 2018). Hope has indeed a positive effect on well-being (Counted et al., 2022), and therefore, fewer psychological difficulties result in better family functioning (Olson, 2000). This study has limitations that should be highlighted, such as the absence of socioeconomic data, the sample size that included mostly women living in the family context, the cross-sectional design that does not allow causal inferences, and the exclusive use of self-report measures. Also, the results should be interpreted with caution because of the restrictions and variation on individuals’ social interaction in the period of data collection (i.e., the population was under stay-at-home confinement until May 2020, and after that teleworking and some other limitations continued, such as social distancing, mask use, restrictions on store hours). However, this phase corresponded to the first wave of COVID-19, so its impact on the individual and the family is still critical due to the uncertainty and lack of knowledge about the evolution of the pandemic, regardless of the scope of social interaction limitations. Despite these limitations, the present study provides several contributions at a theoretical and practical level, particularly for Portuguese women adults. In the first instance, this study corroborates other investigations and adds the moderating role of hope in the relationship between family satisfaction and family functioning, which contributes to understanding how family satisfaction may have an effect on family functioning in Portuguese individuals during stressful events, such as COVID-19 pandemic. Future research should employ a longitudinal design, a larger mixed sample to replicate the present study, and control the socioeconomic status of the sample including as well COVID-19 diagnosed individuals and assess also family members on the role of coping on family functioning. In this study, it is important to highlight that teleworking, being able to identify paths to goals, and/or having the ability to achieve the results, greater family satisfaction, and greater psychological well-being were positively associated with family functioning. Also, the presence of chronic illness in the family was associated with worse family functioning. It was also possible to verify the moderating role of hope in the relationship between family satisfaction and family functioning, which makes it crucial to support families in identifying strategies to achieve goals and promote self-efficacy, that is, the sense of ability to achieve the desired results, during difficult periods such as the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the results, the influence that hope may have on family satisfaction and family functioning, as well as on well-being is significant. Therefore, it is important not only to support families to adapt to the pandemic period through psychological support, but also through interdisciplinary approaches that include support from other entities (e.g., work organizations, health centers, hospitals, and recreational organizations) to provide appropriate responses to families during the COVID-19 pandemic and further related stressor events. At the level of work organizations, the results inform about the positive outcome for families regarding the use of teleworking, since a positive correlation between teleworking and family functioning was found, thus, encouraging businesses/institutions to continue to apply teleworking or to adhere to a hybrid method. The results also showed the importance of providing medical and psychological support for families. The intervention should focus on increasing psychological well-being, hope, and family satisfaction to promote family functioning. Also, it is essential to work with individuals to identify strategies to achieve goals and self-efficacy, in order to promote a greater ability to achieve the desired results, since these are the internal resources that most contribute to family functioning. In turn, the moderating role of hope reinforces the important role of mental health professionals in working on the internal resources of the individual and, for those struggling with COVID-19 issues, mental health interventions are paramount. This study also emphasizes the importance of identifying and signposting families with a chronically ill family member so that the medical and psychological support provided by family physicians and mental health professionals is tailored to the care needs of the family member so that the family member can cope with the different daily challenges (i.e., caring for the family member and caring to prevent COVID-19). Finally, this study clarified the relationships between family functioning and well-being, family satisfaction, and other pertinent variables in the pandemic period, such as teleworking and the added concern of caring for a chronically ill family member. The relationships mentioned above showed the importance of caring during this period and highlight the need for multidisciplinary support to families, emphasizing the role of hope in improving mental health outcomes. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Santos, M., Ferraz, A., Bernardo, A. C., Machado, A. M., Evangelista, M., Ribeiro, I., & Graça Pereira, M. (2023). Family functioning in a Portuguese sample of adults during COVID-19: Does hope matter? Clínica y Salud, 34(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2023a1 References |

Cite this article as: Santos, M., Ferraz, A., Bernardo, A. C., Machado, A. M., Evangelista, M., Ribeiro, I., & Pereira, M. G. (2023). Family Functioning in a Portuguese Sample of Adults during COVID-19: Does Hope Matter?. ClĂnica y Salud, 34(1), 1 - 8. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2023a1

Correspondence: gracep@psi.uminho.pt (M. Graça Pereira).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS