ChildrenŌĆÖs School Subjective Well-Being: The Importance of Schools in Perception of Support Received From Classmates

[El bienestar subjetivo escolar en la infancia: la importancia de la escuela en la percepci├│n del apoyo recibido de los compa├▒eros de clase]

Mari Corominas1, 2, Mònica González-Carrasco1, and Ferran Casas1

1University of Girona, Girona, Spain; 2Barcelona Institute of Childhood and Adolescence, Barcelona, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2021a7

Received 23 September 2019, Accepted 17 August 2020

Abstract

Besides educational results, a comprehensive view of childhood should include children’s opinions on their well-being in school. The objective of this study is to determine whether school subjective well-being of children varies according to the school they attend, which would justify identifying related factors (school perceptions, individual affection, and socioeconomic composition). The 3,962 answers of children from Barcelona (Mage = 10.74) in 2017 to the International Survey of Children’s Well-being are analysed. The multilevel analysis shows that classmates play an essential role in school experience: in those schools where more children are very satisfied with their life as students, children have more confidence in receiving support from their classmates if they have a problem and feel less stressed. This has important implications for learning, coexistence, and participation. As the impact of social inequalities on school experience has not been identified, research focused on schools facing situations of social vulnerability is required.

Resumen

Además de los resultados educativos, una visión integral de la infancia debe incluir las opiniones de los niños sobre su bienestar en la escuela. El objetivo del trabajo es determinar si el bienestar subjetivo escolar de los niños varía según la escuela a la que asisten, lo que justificaría identificar factores relacionados (percepciones escolares, afecto individual y composición socioeconómica). Se analizan las 3,962 respuestas de los niños de Barcelona (Medad = 10,74) a la Encuesta Internacional de Bienestar Infantil en 2017. El análisis multinivel muestra que los compañeros de clase juegan un papel esencial en la experiencia escolar: en aquellas escuelas donde hay más niños satisfechos con su vida escolar tienen más confianza en recibir el apoyo de sus compañeros de clase si tienen un problema y se sienten menos estresados. Esto tiene importantes implicaciones para el aprendizaje, la convivencia y la participación. Dado que no se ha identificado el impacto de las desigualdades sociales en la experiencia escolar, se requiere una investigación centrada en las escuelas que se enfrentan a situaciones de vulnerabilidad social.

Palabras clave

Ni├▒os, Bienestar subjetivo, Apoyo de los compa├▒eros de clase, Escolarizaci├│n, ISCWeBKeywords

Children, Subjective well-being, Classmates support, Schooling, ISCWeBCite this article as: Corominas, M., González-Carrasco, M., and Casas, F. (2022). ChildrenŌĆÖs School Subjective Well-Being: The Importance of Schools in Perception of Support Received From Classmates. Psicolog├Ła Educativa, 28(2), 99 - 109. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2021a7

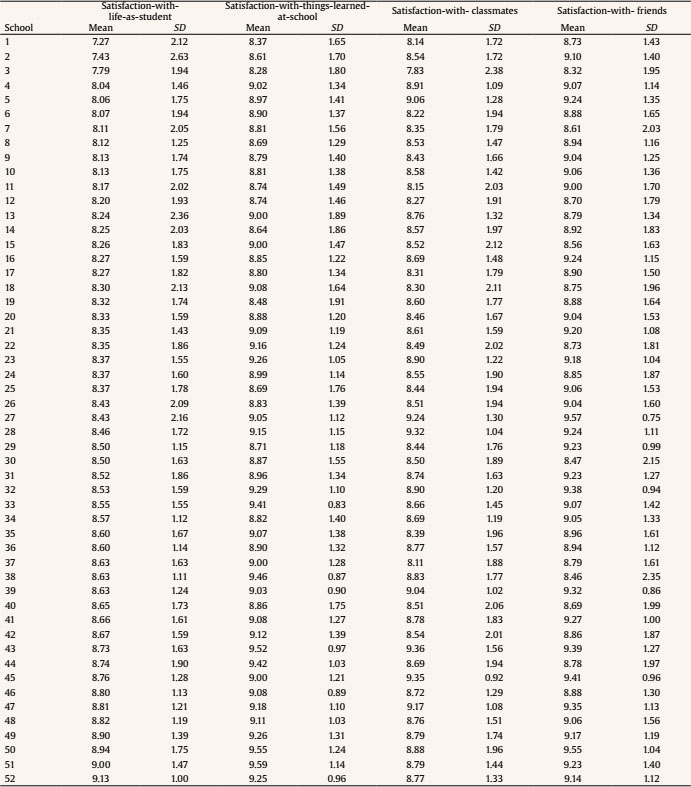

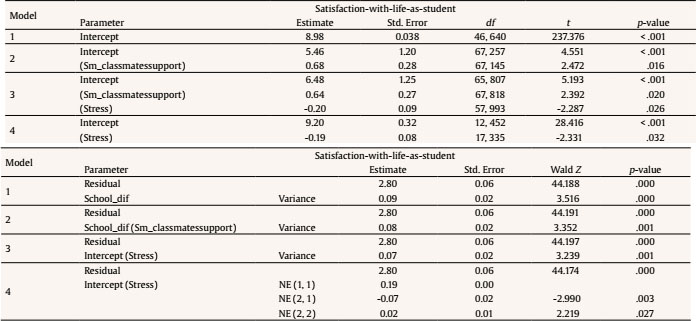

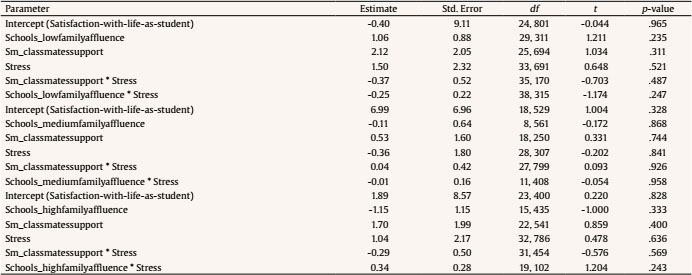

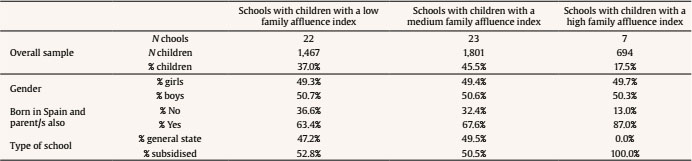

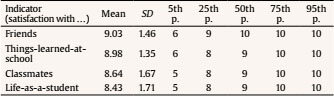

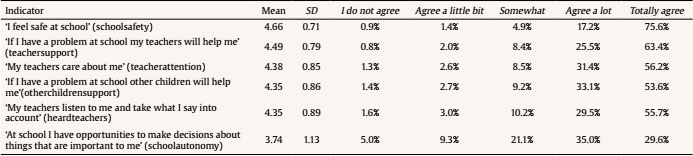

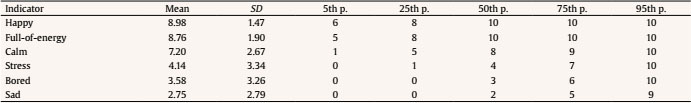

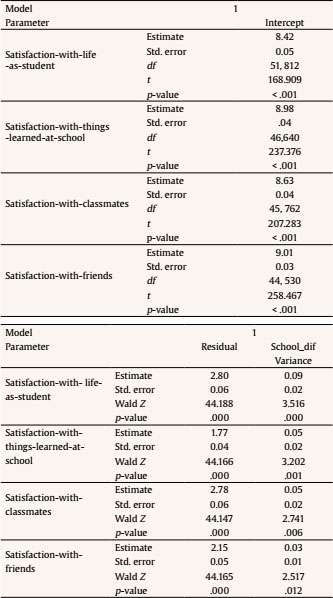

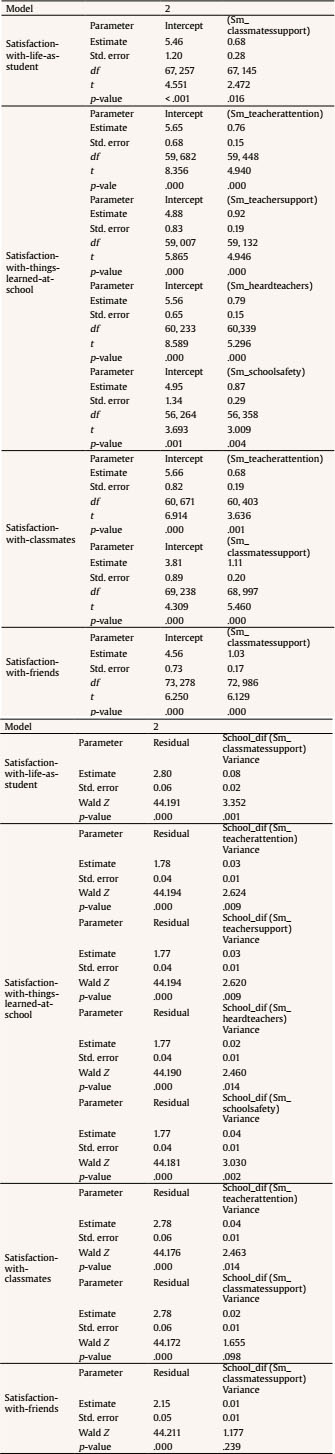

mari.corominas@udg.edu Correspondencia: mari.corominas@udg.edu (M. Corominas).Why We Should Guarantee Children’s Well-being in Schooling and Education? The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) states that both families and the state must educate and socialise (McAuley & Rose, 2010). According to Marguerit et al. (2018), all countries belonging to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), not to mention other organizations, are found wanting when it comes to ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting lifelong learning opportunities (the fourth sustainable development goal, SDG). In this regard, the UNICEF Catalonia Committee and UNICEF Spanish Committee (2018) have prioritized the goal of quality education, together with ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being (the third SDG). In practically all OECD countries, there is nearly universal coverage of basic education, as enrolment rates attain or exceed 95% (OECD, 2019). In Spain specifically, there were around 3,000,000 students in primary education in 2018 (Spanish Ministry of Education Culture and Sports, 2018), while for the Catalan education system this figure was around 500,000 (Catalonia Department of Education, 2018). In both aforementioned education systems, the goal of primary education is to facilitate the learning of oral expression, comprehension techniques, reading, writing, numeracy, and cultural skills. Social skills, work and study habits, artistic sense, creativity, and affectivity are also developed at this stage, as children’s individual needs are taken into consideration for the purpose of developing their personalities and preparing them for secondary education (Mullis, Martin, Goh, et al., 2017). For instance, according to the 2016 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study, and similarly to same studies for mathematics and science (Martin et al., 2016; Mullis et al., 2016; Mullis, Martin, Foy, et al., 2017), Spain was one of the highest achieving countries for Year 4 pupils (usually aged 9-10) for the period 2011-2016, along with Austria, Bulgaria, England, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Norway, Slovenia, and Sweden. Schools play an important role in improving emotional well-being for 21st-century children, since teachers help raise their self-esteem and motivation by being a role model, mentor, and educator (Choi, 2018). For Jiang et al. (2014), the UNCRC constitutes a framework for promoting children’s well-being in schooling and education by affording them provision, protection, and participation rights. Regarding provision rights, schools should be easily and readily accessible to all children and provide them with opportunities for development (related to the right to education, the goals of education included in the UNCRC, and knowing their rights). As for protection rights, schools should protect children from physical, mental, or any other danger (the right to protection from all forms of violence). And, finally, in terms of participation rights, schools need to ensure children have a variety of participation and self-determination rights (freedom of expression and association) (United Nations, 1989). Therefore, when addressing the SDG of ‘quality education’ and ‘ensure healthy lives and promote well-being’, and considering the previous framework for promoting children’s well-being in schooling and education, one issue is whether ‘children’s school subjective well-being (SWB)’ should be integrated together with educational results indicators to better understand the school lives of children. Besides educational result indicators, a comprehensive view of childhood should include children’s opinions on their well-being in school and education in order to promote that in schools. This represents an opportunity for improving schooling, teacher training, and the identification of educational problems or needs. A relevant question, then, is whether we must depart from the premise that ‘children’s school SWB’ is the same in all schools or otherwise assume that it varies according to the school, which would justify identifying the related factors involved at the school level. What Should We Consider when Promoting ‘Children’s School SWB’? Children’s SWB, that is, their satisfaction with life and different aspects of their lives – including satisfaction with school experience and other school aspects, referred to here as children’s school SWB – usually decreases with age (Casas & González-Carrasco, 2018; Savahl, 2017). It may also vary according to gender, home context, family/peer/teacher relationships, school context, and neighbourhood quality, rather than gross domestic product or income inequality (Newland et al., 2018). In prior studies, children who knew their rights demonstrated higher SWB than those reporting otherwise (Casas et al., 2018). And with regard to children’s school SWB, Casas and González-Carrasco (2017) underlined that, in children’s minds, satisfaction with life as a student and satisfaction with school experiences extend far beyond the boundaries of the school. When satisfaction with teachers and peers is high, children consider school as one world, and when one of the two dimensions does not provide enough satisfaction, they represent school as two different worlds. In different countries, including Estonia, Germany, Malta, Norway, Poland, Romania, Spain, and the UK, in cases of low SWB, girls’ SWB was driven by relational factors such as satisfaction with peers, whilst for boys school was the main factor (Kaye-Tzadok et al. 2017). Children’s school SWB has also been found to decrease with age and depend on how their teachers and schoolmates treat them, as well as how safe they feel at school (Kutsar & Kasearu, 2017). Corominas et al. (2020) suggested that children’s voices being adequately heard by adults, including teachers, could be the first step to giving attention to children and improving their SWB. In addition to school satisfaction, bullying is also a relevant issue in children’s SWB (Dinisman et al., 2015; Lawler et al., 2015). Children who report having been bullied at school display lower SWB, this being related to being older, a girl, and materially deprived (Bradshaw et al., 2017). In their study, Savahl et al. (2018) found that although some children being bullied presented acceptable levels of life satisfaction, they may still be at risk, as there may have adverse psychological outcomes. Zarate-Garza et al. (2017) suggested that chronic peer victimization could have physiological and mental health consequences, and that physiological response to stress is critical. In relation to school perceptions, and considering that children make relevant groups of friends from the networks created with classmates (Ivaniushina & Alexandrov, 2017), support from family and friends predict satisfaction with life and with school experience in children aged 10-12, support from friends being a more important predictor than family support (Oriol et al., 2017). According to Holder and Coleman (2015), children’s friendships are closely associated with children’s well-being, greater self-worth, and coping skills later in life. They found that children who enjoy close friendships experience higher levels of happiness, life satisfaction, and self-esteem and lower levels of loneliness, depression, and victimization. The group socialization theory of development (Harris, 1995; López-Larrosa, 2015) holds that parents do not have important long-term effects on the development of a child’s personality. This is because socialization is context-specific and outside the home takes place in children and adolescents’ peer groups, where intra- and intergroup processes are responsible for transmitting culture and environmentally modifying personality. In relation to schooling and considering the influence of affection on SWB (Russell, 2003), Kutsyuruba et al. (2015) found that a positive school climate, a safe school environment, and favourable well-being are all critical to children’s academic, emotional, and social needs. They therefore stress the importance of remembering that children’s educational experience occurs in classrooms, peer groups, school, the school board, and the neighbourhood. Sancassiani et al. (2015) found that targeting social and emotional competences and attitudes about oneself, others, and school is useful for enhancing healthy behaviours, promoting psychological well-being and improving academic performance. Meanwhile, Cheney et al. (2014) argued that psychological interventions in schools are related to social and emotional aspects of learning, as well as cognitive, behavoural and social skills. De Róiste et al. (2012) emphasized the relevance of school participation for children, and identified positive relationships between school participation, health, and well-being. Participation in school was associated with school pleasure and higher perceived academic performance, better self-rated health, higher life satisfaction, and greater reported happiness. Upadaya and Salmela-Aro (2013) highlighted that a high level of school engagement is positively associated with academic success and children’s well-being, and negatively associated with children’s ill-being. John-Akinola and Nic-Gabhainn (2014) also suggested that school participation is relevant for improving the school socio-ecological environment, relationships, and positive health and well-being outcomes of children. Finally, in line with the sociology of education, which identifies patterns, causes, and consequences of inequalities in education (Collet-Sabé, 2019), as well as the peer effect in educational results (Yeung & Nguyen-Hoang, 2016), this article adopts the perspective that these differences may also be observed in children’s school SWB. In relation to the socioeconomic composition of a school’s pupils, peer effect has been found to differ according to peer characteristics (Gottfried, 2014). Children who share a school and neighbourhood show similar levels of educational results (Levine & Painter, 2008), while attending a school with children from more educationally disadvantaged families can result in lower educational results (Chesters & Daly, 2017). However, some findings contradict the argument that disadvantaged socioeconomic children bring down the academic level of the class or the school (Hornstra et al., 2015). Objectives and Hypotheses The main objective of this article is to determine whether children’s school SWB varies according to the school they attend, which, if found to be the case, would justify identifying related factors at the school level. Therefore, there is a need to ascertain whether differences exist between schools in relation to pupils’ school satisfaction and identify related factors such as school perceptions, individual affection, and the socioeconomic composition of pupils attending the school. The specific objectives and hypotheses are presented below: Objective 1: At the school level, to determine the level of children’s school SWB measured through the following indicators: satisfaction with ‘your life as a student’, ‘things you have learned at school’, ‘other children in your class’, and ‘friends’. Hypothesis 1: Children will report different degrees of satisfaction with their life as a student, things learned at school, children in their class and friends according to the school they attend. Objective 2: At the school level, to determine to what extent children’s school SWB is related to school perceptions through indicators measuring agreement with levels of school safety, teacher support, teacher attention, classmates support, being heard by teachers, and school autonomy. Hypothesis 2: Children in schools where there are higher mean scores for school satisfaction will display higher mean scores for all school perceptions (school safety, teacher support, teacher attention, classmates support, being heard by teachers and school autonomy). Objective 3: At the school level, to determine to what extent children’s school SWB and school perceptions are related to higher or lower scores on individual affection. Hypothesis 3: Children in schools where there are higher mean scores for school satisfaction and school perceptions will report higher individual scores for positive affection (being happier, fuller of energy, or calmer) and lower scores for negative affection (being less sad, bored, or stressed). Objective 4: At the school level, to determine whether the socioeconomic composition of pupils at the school is related to school satisfaction, school perceptions, and individual affection. Hypothesis 4: Children in schools where there are higher mean scores for school satisfaction and school perceptions, as well as higher mean scores for individual positive affection and lower mean scores for individual negative affection, attend schools with a higher socioeconomic composition of pupils. Research Design The research employed a cross-sectional survey: children’s school SWB was measured using the answers given by children aged 10-12 to an adapted preliminary version of the third International Survey of Children’s Well-Being (Andresen et al., 2020). Data collection took place in Barcelona city in 2017 as part of ‘The Children Have Their Say’ programme, which is included within the childhood policy framework ‘A Blueprint for Childhood and Citizen Focus 2017-2020’ (Barcelona City Council, 2017). The most applicable items from the survey were selected according to the references presented in the previous section regarding children’s school SWB (see Instruments section). Participants The sampling design and sample characteristics for the survey are detailed in Corominas et al. (2020). It comprises a probabilistic sample of Year 5 and 6 pupils (the last years of primary education) in Barcelona city in 2017 (mean age = 10.74, SD = 0.68). A total of 3,962 surveys were analysed from 52 different schools and 170 different class groups. When a school had one or two class groups, all were selected (42 schools), and when there were more than two class groups, two were selected randomly (10 schools). Nine questionnaires were excluded out of 3,971 because less than 40% of the items were responded to (analysed sample = 3,962). The socioeconomic composition of pupils at the schools was constructed via the question ‘What neighbourhood do you live in?’, which was cross-referenced with the ‘2017 Family Income Index’ (Barcelona City Council, 2019). The ‘2017 Family Income Index’ is an indicator of mean income level of residents in the 73 neighbourhoods of Barcelona city. A numerical value corresponding to the family income of the neighbourhood where the child is living is assigned to each child. This was therefore used to calculate the mean income of children at each school. Three categories were created according to the thresholds established by the source that provides the Family Income Index. This variable has been constructed for multilevel analysis, and the table below shows its relationship with gender, birth, and type of school (Table 1). Instruments Children’s school SWB. This was measured using 4 indicators that are derived from a proposal for items on satisfaction with school (Casas et al., 2013) and the Brief Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS) (Seligson et al., 2003). Indicators related to school satisfaction are ‘satisfaction with your life as a student’, ‘things you have learned at school’, and ‘other children in your class’ (classmates). Satisfaction with ‘your friends’ is derived from the BMSLSS. They were measured using 11-point scales, where 0 meant not at all satisfied and 10 totally satisfied. In this research, the median for the items was always 9 or 10, which means that more than a half of the children were very satisfied. And the value for the 5th percentile was usually 6 or less, which means that dissatisfaction was reported only infrequently (Table 2). School perceptions. This was measured using 6 indicators related to the child’s interpersonal relationships at school (5-point scales, where 0 meant I do not agree and 5 I totally agree). All mean scores were above 3.7, meaning that more than a half of the children agreed a lot or totally with the items, while less than a quarter usually did not agree or agreed only a little (Table 3). Affection. This was measured using 6 indicators derived from Russell’s Core Affect Theory (Russell, 2003). An 11-point scale was used, where 0 meant not at all and 10 all the time during the previous two weeks. Positive Affect items showed the highest means (more than a half of the children reported being very happy and full of energy, and more than a quarter very calm). In relation to Negative Affect, no more than a quarter said they were very stressed, bored or sad (Table 4). Data Analysis Since the aim is to determine whether the individual school has an effect on children’s school SWB and the data are grouped by school, the adopted analytical strategy is based on adjusting and interpreting a multilevel analysis in five stages with SPSS, following the steps defined by Pardo et al. (2007). The structure of the data used in this article is similar to theirs. In this sense, the multilevel analysis allows estimating, separately, the variance between students from the same school and the variance between schools. Firstly, an one-way analysis of variance with random effects (Model 1) shows whether there are mean differences in children’s school SWB between schools. Secondly, a regression analysis with means as outcomes (Model 2) shows whether mean differences in children’s school SWB between schools can be attributed to the mean school perceptions of children belonging to each school. Thirdly and fourthly, a one-way analysis of covariance with random effects (Model 3) and a regression analysis with random coefficients (Model 4) show whether the differential relationship between children’s school SWB and school perceptions of each school are related to the individual affection reported by each child. And, finally, a regression analysis with means and slopes as outcomes (Model 5) shows whether the differential relationship between children’s school SWB and school perceptions in each school and their relationship with the individual affection reported by each child depends on the socioeconomic composition of the pupils attending the schools. All relevant statistical information for each model is provided in Results section (parameter, mean estimate, standard error, degrees of freedom, t-value, Wald Z value, and p-value). It should be noted that although the data are grouped into class groups by school, an analysis of differences between class groups was discarded due to the absence of sufficient internal statistical mean differences between class groups in each school. Besides that, the children also gave their general opinion of the school rather than of their concrete classroom experience. Also note that ‘No response’ and ‘Do not know’ options were not considered for analysis. The mean percentage of missing data across the analysed indicators was low, 1.33%, and, therefore, no imputation procedure was applied. Are there Differences in Children’s School SWB between Schools? In the survey conducted, the children reported that they were more satisfied with their life as a student, things learned at school, children in their class, and friends depending on the school they attended. That said, differences between schools were somewhat greater for satisfaction with ‘life as a student’ and ‘things you have learned at school’ than for satisfaction with ‘other children in your class’ and ‘your friends’. At the school level, variance existed within schools for each of the satisfaction domains analysed (that is, there were children with different levels of satisfaction in the same school) and, at the same time, this variance within school also varied between schools (that is, children with higher or lower levels of satisfaction used to attend the same schools). A model considering level of satisfaction by school effect is better than one without because mean school satisfaction can differ significantly. Table 5 shows mean levels of school satisfaction and their standard deviations. Table 5 Mean School Satisfaction (from lowest to highest according to the first variable)   Note. p. = percentile Specifically, as shown in Table 6, at school level, school mean for satisfaction with ‘life as a student’ was 8.42 (SD = 0.05), being variance within schools 2.80, and variance between schools 0.09. Therefore, 3.0% (coefficient of intraclass correlation, IC) of variance between schools corresponded to school mean differences. Secondly, the school mean for satisfaction with ‘things you have learned at school’ was 8.98 (SD = 0.04), being variance within schools 1.77, and variance between schools 0.05. Therefore, 2.6% (IC) of variance between schools corresponded to school mean differences. Thirdly, the school mean for satisfaction with ‘other children in your class’ was 8.63 (SD = 0.04), being variance within schools 2.78, and variance between schools 0.05. Therefore, 1.8% (IC) of variance between schools corresponded to school mean differences. And, finally, the school mean for satisfaction with ‘your friends’ was 9.01 (SD = 0.03), being variance within schools 2.15, and variance between schools 0.03 (Table 6). Therefore, 1.5% (IC) of variance between schools corresponded to school mean differences. Can Differences in Children’s School SWB between Schools be Attributed to School Perceptions at Each School? Some specific school perceptions contributed to statistically significant mean differences between schools in children’s school SWB. Children in schools with a higher school SWB also displayed, at the school level, a higher mean in some specific school perceptions (school safety, teacher support, teacher attention, classmates support, and heard by teachers). One of the children’s school perceptions (school autonomy) was not statistically related to any of the indicators related to school satisfaction considered here. Firstly, as shown in Table 7, at school level, school mean for satisfaction with ‘life as a student’ was related to ‘If I have a problem at school other children will help me’ (intersection = 5.46, coefficient = 0.68, p-value = .016). Secondly, school mean for satisfaction with ‘things you have learned at school’ was related to ‘My teachers care about me’ (intersection = 5.65, coefficient = 0.76, p-value = .000), ‘If I have a problem at school my teachers will help me’ (intersection = 4.88, coefficient = 0.92, p-value = .000), ‘My teachers listen to me and take what I say into account’ (intersection = 5.56, coefficient = 0.79, p-value = .000), and ‘I feel safe at school’ (intersection = 4.95, coefficient = 0.87, p-value = .004). Thirdly, the school mean for satisfaction with ‘other children in your class’ was related to ‘My teachers care about me’ (intersection = 5.66, coefficient = 0.68, p-value = .001), and ‘If I have a problem at school other children will help me’ (intersection = 3.81, coefficient = 1.11, p-value = .000). Note that school variance is not statistically significant (p-value = .098). And, finally, the school mean for satisfaction with ‘your friends’ was related to ‘If I have a problem at school other children will help me’ (intersection = 4.56, coefficient = 1.03, p-value = .000). Note that school variance is not statistically significant (p-value = .239). Is the Differential Relationship between Children’s School SWB and School Perceptions of Each School Related to the Individual Affection Experienced by Each Child? Children in schools with higher means for school satisfaction and some specific higher means for school perceptions reported feeling different levels of affection. Specifically, children in schools expressing higher mean school satisfaction with ‘life as a student’, given a higher school mean for ‘If I have a problem at school other children will help me’, reported feeling less stressed. As shown in Table 8, there is a statistically significant relationship: between schools, where the school mean for satisfaction with ‘life as a student’ (mean = 6.48) has correspondence with ‘If I have a problem at school other children will help me’ (coefficient = 0.64, p-value = .020) and, individually within schools, ‘feeling less stressed’ (coefficient = -0.20, p-value = .026). Note that variability between schools has decreased slightly, from 0.075 (Model 2) to 0.067 (Model 3). Table 8 Results of One-way Analysis of Covariance with Random Effects and Regression Analysis with Random Coefficients (Models 3 and 4)   Note. p. = percentile Does the Differential Relationship between Children’s School SWB and School Perceptions of Each School and its Relationship with the Individual Affection Experienced by Each Child Vary Depending on the Socioeconomic Composition of the Pupils Attending the Schools? Finally, according to this statistical analysis, the socioeconomic composition of the schools (low, medium or high) did not contribute to the identified relationship (Table 9). Table 9 Results of Regression Analysis with Means and Slopes as Outcomes (Model 5)   Note. p. = percentile The Importance of Schools in Children’s Perception of Support Received from Classmates Bearing in mind the theoretical background of this article, quality in education is closely linked to the promotion of children’s well being, and teachers serve as role models, mentors, and educators in the promotion of children’s school SWB (Choi, 2018; Jiang et al., 2014; Marguerit et al., 2018; UNICEF Catalonia Committee & UNICEF Spanish Committee, 2018). Indeed, as the results of this article suggest, learning-related and classmate-related dimensions are equally essential to a good school experience; that is, school should represent a unique harmonic world in children’s minds (Casas & González-Carrasco, 2017). Some research has already reported that negative attitudes attached to different school subjects were negatively related to school SWB (Fries et al., 2007), and that high-performing girls and boys in mathematics also manifested high enjoyment and low anxiety and boredom (Jang & Liu, 2012). In this article, it is argued that, beyond educational results (Martin et al., 2016; Mullis et al., 2016; Mullis, Martin, Foy, et al., 2017), knowing children’s relationship with their teachers and classmates helps us to understand their school experience (Kaye-Tzadok et al., 2017; Kutsar & Kasearu, 2017; Newland et al., 2018). For a child, being adequately heard by adults, including teachers, could be the first step in giving attention to children and improving their SWB (Corominas et al., 2020). This analysis also reveals that classmates play an essential role in the school experience, since in those schools where more children have confidence in receiving support from their classmates if they have a problem, children are more satisfied with life as a student and feel less stressed. This finding could be explained by the group socialization theory of development posited by Harris (1995), as interpreted by López-Larrosa (2015). That is, interpersonal relationships developed in the socialization process at school are important for both school and overall SWB. Some research has already revealed that peer interaction plays a particularly important role in children’s school SWB, since functional relationships with peers have been reported to be a major source of satisfaction, while destructive friction in peer groups is considered a core source of anxiety and distress by pupils (Pyhältö et al., 2010). Moreover, social support can be considered to be predictive of pupils’ investment and interest in personal work and success, although only when pupils pursue achievement and future goals (Hernandez et al., 2016). In relation to affection or stress, some research has also already shown perceived peer acceptance to contribute to lower levels of social anxiety, as well as self-consciousness (Mallet & Rodriguez-Tomé, 1999). Additionally, in order to integrate education and mental health in schools, some resilience-based interventions are currently protocoled in Europe from a whole school approach to promote a culture of mental well-being and prevent mental disorders by enhancing resilience capacities in adolescents aged 12-14 (Las Hayas et al., 2019). Keeping this in mind, what can we do to ensure that all children treat each other well and support one another at school? Alongside educational results indicators, what importance should we give to children’s school SWB indicators? Implications for Learning In order to provide children with more opportunities for development in accordance with their right to education and UNCRC’s educational goals (United Nations, 1989), when considering the actions of classmates, it may be relevant to promote interventions targeting social and emotional competences and attitudes about oneself, others and the school, which will be based around creating a positive school climate and a safe school environment (Cheney et al., 2014; Kutsyuruba et al., 2015; Sancassiani et al., 2015). What is more, a first step could be to create more favourable conditions for socializing with classmates and friends, aspects related to children’s SWB (Holder & Coleman, 2015; Ivaniushina & Alexandrov, 2017; Oriol et al., 2017). In relation to educational results, this analysis reveals that it is relevant to consider that, at school level, satisfaction with ‘things you have learned at school’ is related to teachers’ actions (‘My teachers care about me’, ‘If I have a problem at school my teachers will help me’, ‘My teachers listen to me and take what I say into account’, and ‘I feel safe at school’). This shows that teachers’ actions have an impact on children’s learning processes and are therefore relevant to learning. Some research has already posited that social anxiety is positively associated with a greater self-reported likelihood of approaching teachers for support (Leeves & Banerjee, 2014), and that the higher the children perceive conditional support from their teacher, the lower their self-perceived school competence (Hascoët et al., 2018). Other findings support the notion that maintaining a positive teacher-pupil relationship and encouraging teachers in the role of positive motivators could be effective in prevention and intervention programmes aimed at offsetting the decline in individual school self-concept and achievement motivation (Bakadorova & Raufelder, 2014). Implications for Coexistence In order to shield children from danger in accordance with the commitment to protect them from all forms of violence (United Nations, 1989), when considering the actions of classmates and how these relate to bullying, the favourable perception of peers may be an indicator of school experience, either individually or as a group. This link is crucial, because bullying is not always clearly observable in school environment, but carries high risks and long-term health outcomes (Bradshaw et al., 2017; Dinisman et al., 2015; Lawler et al., 2015; Savahl et al., 2018; Zarate-Garza et al., 2017). Moreover, from this analysis, it is pertinent to consider that, at school level, satisfaction with ‘other children in your class’ is related to ‘My teachers care about me’ and ‘If I have a problem at school other children will help me’, the same than in the case of satisfaction with ‘your friends’. This suggests that teachers have an important role in pupils’ interpersonal relationships established in the classrooms and their contribution to children’s school SWB in a broad sense. In addition, some other research has suggested that pupils’ psychosocial characteristics and social climate in the classroom may affect academic achievement (Bennacer, 2000), and that collective efficacy or joining together could be useful for understanding academic achievement in some types of schools (Pina-Neves et al, 2013). Implications for Participation One strategy for improving provision and protection rights (United Nations, 1989) could be promotion of participation and self-determination in schools (de Róiste et al., 2012; John-Akinola & Nic-Gabhainn, 2014; Upadaya & Salmela-Aro, 2013). On the one hand, as explained previously, this analysis reveals that, at school level, ‘My teachers listen to me and take what I say into account’ is related to satisfaction with ‘things you have learned at school’. However, from this analysis, and also at school level, ‘At school I have opportunities to make decisions about things that are important to me’ is not related to any school satisfaction indicator. This may be due to the fact that ‘At school I have opportunities to make decisions about things that are important to me’ is the school perception with the lowest score (see Table 3). Thus, when an action has a low prevalence, although it will not have any statistical effect, it is important to take note of the low frequency because it informs that children do not perceive having enough autonomy at school. Limitations and Further Research Finally, these results reveal that children’s school SWB may vary depending on which school they attend, since there are statistically significant mean differences between schools in relation to children’s satisfaction with ‘their life as a student’ and ‘things learned at school’, as well as with ‘children in their class’ and ‘friends’. This would justify asking children ‘how they are’ at school, so as to know related factors and understand more about their lives at school. However, differences between schools in children’s school SWB are only partially attributable to the variables analysed in this article and caution is required when generalizing the results. For instance, it might be advisable to know children’s self-concept (Galindo-Domínguez, 2019), since adolescents with high self-concept show significantly higher scores in satisfaction with life and positive affect and lower scores in negative affect (Ramos-Díaz et al., 2017), and there are significant differencesbetween self-esteem and socioeconomic status in some samples (Tabernero et al., 2017). Moreover, social inequalities have an impact on aspects of children’s schooling and education (Collet-Sabé, 2019; Chesters & Daly, 2017; Gottfried, 2014; Hornstra et al., 2015; Levine & Painter, 2008; Yeung & Nguyen-Hoang, 2016). However, based on this analysis, in any type of school with a different socioeconomic composition and so possibly depending on other environmental factors, pupils are satisfied (or dissatisfied) with their life as a student if they perceive that other children will help them if they have a problem at school, this school perception being related to feeling less stressed on a day-to-day basis. Further research is therefore required with other types of measures to focus on school SWB of children affected by social inequalities. Taking all of the above into account, it would be advisable to carry out further research, also qualitative, to enquire about children’s school SWB and promote it among children themselves. In the context of this analysis, further research could focus on the integrated analysis of educational results and children’s school SWB indicators for a more adjusted comprehension of schooling and education. In all schools with high educational results, are all children very satisfied with their life as a student, the things learned at school and their classmates? What happens in schools with low educational results? In other words, how school SWB is part of the educational experience and impacts educational results? There is also a need to develop multilevel analysis that accounts for socioeconomic composition and peer effect and integrate it in greater depth. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Corominas, M., González-Carrasco, M., & Casas, F. (2021). Children’s school subjective well-being: The importance of schools in perception of support received from classmates. Psicología Educativa, 28(2), 99-109. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2021a7 Funding: This work was possible thanks to the predoctoral contract of Mari Corominas financed in equal parts by the University of Girona and the Barcelona Institute of Childhood and Adolescence (public call ‘IFUdG2017’). References |

Cite this article as: Corominas, M., González-Carrasco, M., and Casas, F. (2022). ChildrenŌĆÖs School Subjective Well-Being: The Importance of Schools in Perception of Support Received From Classmates. Psicolog├Ła Educativa, 28(2), 99 - 109. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2021a7

mari.corominas@udg.edu Correspondencia: mari.corominas@udg.edu (M. Corominas).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS