Evidence-based Standards in the Design of Family Support Programmes in Spain

[Estándares basados en la evidencia en el diseño de programas de apoyo familiar en España]

Isabel M. Bernedo1, M. Angels Balsells2, Lucía González-Pasarín1, and M. Angeles Espinosa2

1University of Malaga, Spain; 2University of Lleida, Spain; 3Autonomous University of Madrid, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2022a6

Received 9 March 2022, Accepted 28 June 2022

Abstract

The positive parenting approach has highlighted the importance of supporting families to perform the functions associated with their parental role and to improve children’s well-being. The aims of this study were to identify and describe the characteristics of family support programmes in Spain, and to examine the extent to which they meet evidence-based standards for programme formulation. The sample includes 57 programmes identified by the Spanish Family Support Network, which belongs to the pan-European Family Support Network(EurofamNet) . Frequency analyses and contingency tables were carried out. The results show that the Spanish programmes meet several evidence-based standards for programme formulation (i.e., manualization). However, further efforts are required in some areas, such as universality and interdisciplinarity of family support programmes. The findings provide a platform from which to design new initiatives in accordance with standards for prevention programmes, and inform stakeholders and politicians in drawing up evidence-based public policies.

Resumen

El enfoque de parentalidad positiva ha puesto de manifiesto la importancia de apoyar a las familias en el ejercicio de las funciones asociadas a su rol parental y para que aumenten el bienestar de los niños. Los objetivos de este estudio fueron identificar y describir las características de los programas de apoyo a la familia en España y examinar en qué medida cumplen con los estándares basados en la evidencia para la formulación de programas. La muestra incluye 57 programas identificados por la Red Española de Apoyo a la Familia, que pertenece a la Red Paneuropea de Apoyo a la Familia (EurofamNet). Se realizaron análisis de frecuencia y tablas de contingencia. Los resultados muestran que los programas españoles cumplen varios estándares basados en la evidencia para la formulación de programas (por ejemplo, que están manualizados). Sin embargo, es necesario realizar más esfuerzos en algunas áreas, como la universalidad y la interdisciplinariedad de los programas de apoyo familiar. Los resultados proporcionan una plataforma desde la que diseñar nuevas iniciativas de acuerdo con los estándares de los programas de prevención, y orientan a las partes interesadas y a los políticos en la elaboración de políticas públicas basadas en la evidencia.

Palabras clave

Programas basados en la evidencia, Apoyo familiar, Normas de calidad, Formulaci├│n de programas, Desarrollo de capacidadesKeywords

Evidence-based programmes, Family support, Quality standards, Programme formulation, Capacity buildingCite this article as: Bernedo, I. M., Balsells, M. A., González-Pasarín, L., & Espinosa, M. A. (2023). Evidence-based Standards in the Design of Family Support Programmes in Spain. Psicolog├şa Educativa, 29(1), 15 - 23. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2022a6

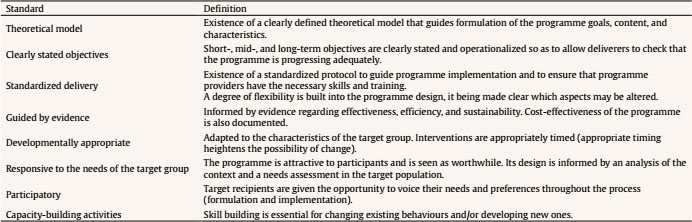

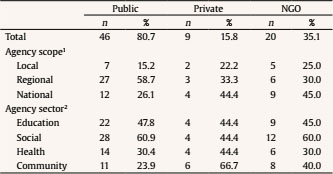

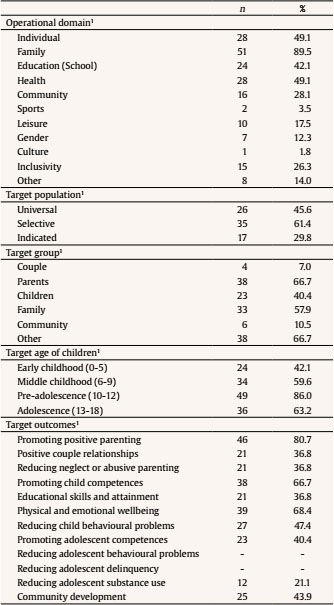

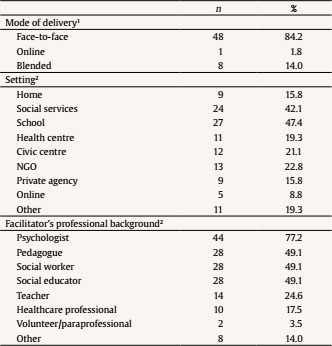

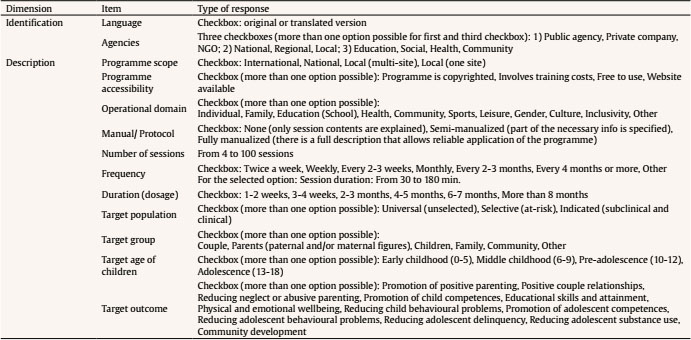

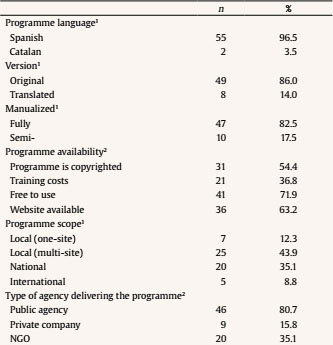

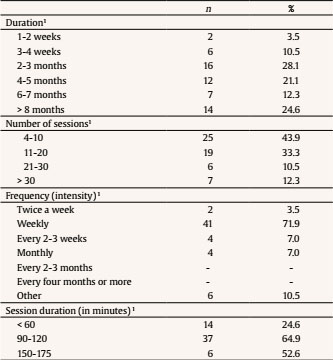

Correspondence: bernedo@uma.es (I. M. Bernedo).Following the publication of the Council of Europe’s (2006) Recommendation Rec(2006)19 on policy to support positive parenting, various family support programmes and services have been developed in Spain with the aim of promoting the development, well-being, and health of children and adolescents. Indeed, parenting support, defined by Daly et al. (2015) as “a range of information, support, education, training, counselling, and other measures or services that focus on influencing how parents understand and carry out their parenting role” (p. 17), has received considerable attention from family care services and the scientific community (Arranz & Rodrigo, 2018; Rodrigo et al., 2015; Rodrigo et al., 2017). Some of the most popular initiatives include workshops to support mothers and fathers in performing their parental responsibilities, the provision of individual family advice and support, and information or psychoeducational sessions for families who are struggling with child rearing (Acquah & Thévenon, 2020; Thévenon, 2020). In Spain, as noted in the introduction to this Special Issue (Rodrigo et al., 2022), these kinds of initiatives have evolved considerably and have become much more common over the past two decades, although not all of them are evidence-based. Ensuring the quality of family support programmes is important, and this has led to an increasing emphasis on evidence-based practice within child, adolescent, and family services. The term “evidence-based programmes” refers to a specific subset of programmes that are theoretically based, with their contents fully described and structured in a manual, their effectiveness evaluated according to standards of evidence, and the factors that influence the implementation process identified and taken into account to explore variations in programme results (Rodrigo, 2016). According to Flay et al. (2005) and Gottfredson et al. (2015), quality standards based on scientific evidence and professional consensus refer to the criteria by which an intervention may be judged efficacious, effective, and ready for dissemination. These standards are applicable across the different stages of programme development, from formulation to subsequent implementation, evaluation, and dissemination. The design of a programme must therefore fulfil a series of conditions that ensure its quality and which support the next stages in its development. Formulating Evidence-based Family Support Programmes One quality standard to consider when designing a family support programme is the extent to which it meets the specific needs of the target population (Asmussen & Brims, 2018). The more clearly families’ capabilities and challenges are identified at the outset, the more likely a programme’s goals and content will be relevant to them. Özdemir et al. (in press) also stress the importance of a clearly defined theoretical model that can explain the mechanisms of change among families; in this respect, both the programme goals and its methods should be consistent with the proposed theoretical model. According to the National Academy for Parenting Practitioners (2008), a high-quality programme is one in which the activities are clearly described and structured so as to enable standardized delivery by other practitioners. In this respect, a programme manual is important for fidelity of implementation (Durlak & DuPre, 2008), although building some flexibility into a programme’s design will allow practitioners to adapt it to the specific needs of families and intervention contexts (Özdemir et al., in press). Other quality standards mentioned by Kumpfer and Alvarado (2003) are that a programme is accessible and adapted to participants, and also that its duration and the frequency of sessions are adequate for meeting the proposed goals. The pan-European Family Support Network (EurofamNet) has developed a generalist and synthetic proposal based on a comprehensive review of academic publications and published quality standards (e.g., Asmussen, 2011; Flay et al., 2005; Gottfredson et al., 2015; Kilburn & Mattox, 2016; Scott, 2010; Small et al., 2009). The qualities that were highlighted in published standards documents and academic publications were combined and reviewed iteratively to identify clusters of terms, as well as the most frequently highlighted aspects of high quality programmes (Özdemir et al., in press). The outcome of this process was a list of eight quality standards related to the formulation of family support programmes (Table 1). Table 1 Quality Standards for the Formulation of Family Support Programmes (Ozdemir et al., in press)   In Spain, the formulation of family support programmes in accordance with evidence-based standards is a relatively recent phenomenon within family welfare and support networks. First evidence-based programmes were aimed at preventing child maltreatment among at-risk families (Menéndez et al., 2010). As Jiménez et al. (2019) argue, however, there is a need to diversify initiatives for at-risk families in accordance with the tenets of progressive universalism, insofar as the majority have been psychoeducational interventions aimed at parents (Hidalgo et al., 2018). Some of the findings in this context are: 1) parents who participated in the group sessions of Crecer felices en familia (“Growing together as a happy family”) programme showed positive changes in parental attitudes and satisfaction and a reduction in parental distress (Álvarez et al., 2015); 2) parental supervision and monitoring improved significantly among single-parent families participating in Vivir la adolescencia en familia (“Navigating adolescence as a family”) programme (Rodríguez et al., 2015); 3) parents who participated in Programa de formación y apoyo familiar (“Family support and training programme”) showed significant changes in affect management in family relations, in perceptions regarding their parental role, and in family functioning (Hidalgo et al., 2015); 4) parental competences and the quality of family interaction improved among at-risk and vulnerable families participating in Aprender juntos, crecer en familia (“Learning together, growing as a family”) programme (Amorós et al., 2015); and 5) families participating in Caminar en familia (“Walking family”) programme (Balsells et al., 2015) while their child was in a temporary foster care placement showed a more accurate perception of the parental role and improved parental self-efficacy, enabling a more positive experience with awareness of progress (Balsells et al., 2018). Although there is now an increasing number of evidence-based programmes aimed at promoting children’s well-being from a more universal perspective (Rodrigo et al., 2017), the effectiveness and efficiency of these programmes require further investigation. Theoretical Foundations of the Positive Parenting Approach The positive parenting approach reflects the findings of systematic research carried out over recent decades, underscoring the influence of certain family context variables on children’s psychological development and highlighting the clear repercussions of this influence on their psychological and social well-being and the protection of their rights (Arranz & Rodrigo, 2018). The Council of Europe’s (2006) Recommendation Rec (2006) 19 defines positive parenting as “parental behaviour based on the best interests of the child that is nurturing, empowering, non-violent and provides recognition and guidance which involves setting boundaries to enable the full development of the child” (Council of Europe, 2006, p. 3). The scientific advances that underpin this definition should inform the theoretical framework of programmes aimed at developing new practices from an ecological, inclusive, and participatory perspective (Balsells et al., 2019). One aspect highlighted by the positive parenting approach is the influence of children on parenting, including their right to participate in family’s socialization processes. This implies that children and adolescents may, through their personal and social competences and resources, interact with and transform their immediate reality (Martín et al., 2013). From this perspective, the child is regarded as competent and capable, and the role of parents is to help the child to exercise his or her rights by providing direction and guidance appropriate to the child’s evolving capacities. In the family setting, therefore, values of mutual respect, equal dignity, authenticity, integrity, and responsibility become the foundations for developing parent-child relationships that promote children’s rights (Daly, 2007). Challenging the unidirectional theories of socialization, this modern view considers socialization as a bidirectional process of mutual adaptation, accommodation, and negotiation performed during complex, ongoing, bidirectional exchanges of parents and children (Grolnick et al., 2007; Kerr et al., 2003; Kuczynski & Parkin 2007). It is worth noting, in this respect, that when children and adolescents are given a participatory role in programmes aimed at promoting positive parenting, they become a catalyst for positive change in the family. When children participate in an intervention, they feel that they are an active part of the process of change by and for their families. This enables increased feedback among family members regarding changes and improvements that benefit the whole family, and in the process children become more aware of their active role in the family environment and in the organization of family life (Mateos et al., 2021). The positive parenting approach also reflects an ecological view of parenting by taking into account the factors that facilitate or hinder this task and by emphasizing the shared responsibility of society and the community in ensuring family well-being and quality of life. Couple and work relationships, support networks within the extended family, friendships, neighbours, and the wider community all contribute to parenting. As Rodrigo et al. (2010) point out, positive parenting does not occur in a vacuum, but rather requires the presence of personal and material support, information and advice, understanding, and, where necessary, skills training to help parents exercise their role and responsibilities. Accordingly, the focus should be placed on the promotion of parental capacities, which means moving toward a strengthening approach that identifies parents’ existing skills and strengths and builds on these capacities. Likewise, interventions should be based on empowering children by promoting their strengths and resources and helping them to communicate their feelings and needs (Rodrigo et al., 2017). In this type of intervention, efforts are made to maximize families’ strengths and to accompany them in making choices to improve their situation rather than imposing solutions (Bérubé et al., 2017). Another aspect to consider concerns how parents may be helped to meet their children’s needs, including through family support programmes. Rock et al. (2015) highlight the diversity of social support strategies and argue that formal and informal sources should be combined in responding to the needs of parents and children. Positive parenting requires of parents the ability to engage adequately with child-rearing tasks so as to ensure their children’s rights and meet their developmental and educational needs in accordance with the sociocultural context (Rodrigo et al., 2009). Consequently, the same kinds of support will not be needed by all families or by an individual family across all stages of its life cycle. As Canavan et al. (2016) point out, family support interventions may be universal, selective or indicated, and the choice will depend on the goals and target population. In most European countries, universal prevention programmes are normally implemented within the context of health and education services, whereas selective or indicated programmes for families with higher levels of needs are usually the responsibility of child welfare and social services (Molinuevo, 2013). These issues raise a series of questions regarding the family support programmes that are now being implemented in Spain. Do they meet evidence-based standards for programme formulation? Do they address key tenets of the positive parenting approach, for example, do they allow for participation by children and adolescents, and are they aimed at building families’ strengths rather than focused exclusively on risk prevention? Are they universal, selective, or indicated? Have they been developed originally in Spain or are they translations of programmes from other countries? Which sectors and agencies are involved in their implementation? In light of the above, the aims of the present study were as follows: a) to identify and describe the family support programmes that are currently implemented in Spain, including the domain in which they seek to obtain results; b) to examine the extent to which they meet evidence-based quality standards for programme formulation; and c) to analyse the relationship between programme design and where (the setting) and by whom (which professionals) a programme is usually implemented. This objectives form part of a project entitled “The pan-European Family Support Research Network: A bottom-up, evidence-based, and multidisciplinary approach” (CA18123), carried out within the framework of the COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology, 2018) programme (www.cost.eu). EurofamNet is a novel initiative involving collaboration among key actors in family support from across Europe aimed at providing evidence-informed responses at European level. Within this context, there are three key targets for research: a) the conceptualization and delivery of family support in Europe; b) quality standards in family support services and evidence-based programmes; and c) advances and agreement on the skills level required within the family support workforce to ensure quality service delivery for families. The second of these research targets is the responsibility of EurofamNet Working Group 3, and one of the actions carried out has been to create a catalogue of family support programmes in Europe (available at: https://eurofamnet.eu/toolbox/catalogue-family-support-programmes). The present study was conducted as part of this action. Programme Sample The sample includes 57 programmes identified by the Spanish Family Support Network in the context of a project undertaken by the pan-European Family Support Network (EurofamNet). The programmes analysed are those that met all the inclusion criteria established by the Spanish Family Support Network, namely authorship (original and/or adaptations), supported by a theoretical model, duration (dosage) of at least four sessions, and report of programme outcomes is provided. The exclusion criteria (anyone of these conditions was enough to exclude) were: organization that delivers the programme not specified, target population is adults but unrelated to parenthood and family issues, programme contents and methodology not specified. Consequently, the sample analysed in this paper does not include all the programmes applied in Spain, but it does reflect the diversity of contexts in which they are applied. Instrument and Data Collection Information about family support programmes was compiled using a Data Collection Sheet (DCS, editable pdf) divided into six sections: 1) programme identification, 2) programme description, 3) programme implementation, 4) programme evaluation, 5) programme impact, and 6) readiness for dissemination. The DCS was created by EurofamNet members in accordance with international quality standards for family support programmes. This paper reports and discusses the findings obtained for the first two of these sections: programme identification and programme description (Table 2). Procedure In order to gather information about family support programmes in Spain, we began by establishing a Spanish Family Support Network involving 25 researchers from 12 Spanish universities, all with experience in the field. We informed them about the purpose of this study (i.e., to describe the characteristics of family support programmes in Spain so as to analyse the extent to which they were formulated in accordance with evidence-based standards) and requested their assistance with data collection. Having agreed to participate, they then received five hours of online training on three aspects: how to apply the inclusion and exclusion criteria for programme selection, how to contact knowledgeable informants (i.e., coordinators and practitioners of child and family services) regarding the programmes that met the inclusion criteria, and how to complete the aforementioned data collection sheet (editable pdf). The lead researcher from each group was responsible for completing the data sheet, which they then had to send to the project coordinator for storage and uploading to the intranet of the EurofamNet project. The project coordinator revised the data files and took responsibility for obtaining any information that was missing. Data collection took place between May 2020 and April 2021. Data Analysis The Spanish data that had been uploaded to the intranet of the EurofamNet project were first exported to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, and then imported into SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., 2017). Frequency analysis and contingency tables were carried out to analyse the characteristics of family support programmes in Spain and the extent to which they had been formulated in accordance with evidence-based standards. Ethical Considerations All the experts who participated in the study took part voluntarily after signing an informed consent form in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was carried out in accordance with the European Cooperation in Science and Technology Association policy on inclusiveness and excellence, as set out in the CA18123 project Memorandum of Understanding (European Cooperation in Science & Technology, 2018). Characteristics of the Family Support Programmes A total of 57 family support programmes were identified as meeting the aforementioned inclusion criteria for analysis (i.e., authorship, supported by a theoretical model, duration at least four sessions, and programme outcomes reported). Tables 3 and 4 show the main characteristics of the 57 programmes. It can be seen (Table 3) that the majority of programmes are original versions in Spanish, fully manualized, free to use, and supported by a website. In terms of their scope, programmes are most commonly implemented across multiple towns or cities at local level (local multi-site). Regarding the agencies involved in programme delivery, they were most commonly public agencies at regional level, although the same programme was sometimes delivered by more than one type of agency and at different levels (local, regional, national). The agencies involved were also linked to a variety of service sectors. This shows there is a multiagency and inter-sectorial approach to family support in Spain (Table 4). Table 4 Characteristics of the Agencies Delivering the Programmes   Note. 1Sum is 100%; 2percentage is for each category for n = 57. With specific respect to public-agency programmes, they are most likely to be delivered at local level across multiple sites (45.7%), to be subject to copyright (50%), to be free to use (71.7%), to involve no training costs, and to be supported by a website (60.9%). Regarding the NGOs involved in programme delivery, they tend to be national in scope (45%), followed by regional (30%) and local (25%) organizations. In terms of the service sectors in which they operate, this is most commonly the social sector (60%), followed by education (45%), community (40%), and health (30%). Regarding programme scope, NGOs are involved in delivering family support programmes both nationally and at the local multi-site level (around 45% in each case). The majority of programmes delivered by NGOs are copyrighted (65%), involve no training costs (55%), are free to use (65%), and supported by a website (70%). Finally, regarding the private agencies involved in delivering family support programmes, they are most likely national in scope (44.4%), followed by regional (33.3%) and local (22.2%) companies. In terms of the sector in which they operate, this is most commonly the community sector (66.7%), with the other three sectors (education, social, and health) being equally represented (44.4%). The majority of programmes with private agency involvement are not subject to copyright (77.8%), are free to use (66.7%), and are supported by a website (77.8%), although around half of them involve some training costs for practitioners. Quality of Programme Design Adequacy of Programme Methodology Regarding the second study objective, the analysis of variables related to the quality of programme design reveals a mixed picture in the extent to which different quality standards are met. With respect to the target outcomes (Table 5), the results show that most programmes aim to promote positive parenting, although they use different approaches to achieve this. Some programmes are focused on building parental skills (approach based on prevention and promotion), while others seek to eliminate risk behaviours (approach based more on a model of deficit and risk). Table 5 Operational Domain, Target Group, and Goals of the Programmes   Note. 1Percentage is for each category for n = 57. Among the programmes with a focus on prevention and promotion, the most common goals are improving children’s physical and emotional well-being, promoting children’s competences in general, promoting adolescents’ social and emotional competences, and community development; a smaller proportion of these programmes seek to promote educational skills and attainment and positive couple relationships. As regards programmes with a more reactive approach based on risk and deficit in the target population, around half are aimed at reducing problem behaviours in adolescence, specifically substance use, along with reducing neglect or abusive parenting (Table 5). As can be seen in Table 5, most of the programmes seek outcomes in the family domain, although the target group of interventions varies. The most common target group is parents (70.6%), followed by the family as a whole (56.9%) and children and adolescents (39.2%). Among the programmes designed to obtain outcomes in the family domain, the primary goal in most cases is to promote positive parenting (86.3%), regardless of who the indirect beneficiary of this is. It is noteworthy that many of these programmes seek to achieve distal outcomes, insofar as 68.6% aim to increase children’s competences, while a similar percentage have the objective of improving children’s physical and emotional well-being – rather than, for example, reducing neglect or abusive parenting (which would be a direct outcome if the target population is parents). In terms of the target age of children, these programmes are aimed mainly at pre-adolescents (88.2%). The formulation of programmes is somewhat different when the aim is to promote the competences and well-being of children and adolescents, or to reduce their behavioural problems. Here, interventions involving parents, the family as a whole or children and adolescents are represented to a similar extent, except for when the goal is specifically to promote children’s physical and emotional well-being, in which case 65.8% of programmes work with parents, 52.6% with children, and 63.2% with the family as a whole. When the aim is to promote positive parenting, however, the percentage of programmes working with children and adolescents is much lower (34.8%), and interventions are targeted primarily at parents (76.1%) or the family as a whole (63%). Regarding the target age of children, the majority of these programmes are aimed at pre-adolescents, with the primary goals being to promote positive parenting (82.6%) and children’s competences (92.1%) and physical and emotional well-being (92.3%). Finally, it is worth noting that none of the family support programmes analysed have the goal of reducing adolescent behaviour problems or delinquency. This suggests that these programmes are aimed more at enhancing positive behaviours than eliminating negative ones, reflecting the tenets of the positive parenting approach. However, despite the high number of programmes that seek improvements in areas that are directly relevant to children and adolescents, the latter are often not part of the target group for interventions. With respect to the frequency of programme delivery (Table 6), the majority involve weekly sessions, primarily with the aim of promoting positive parenting (73.9%), followed by enhancing children’s physical and emotional well-being (66.7%) and competences (65.8%). Once again, we found that regardless of whether the target group was specifically children or the family as a whole, a stated goal of these programmes is improving children’s well-being. With respect to differences by target group, programmes focused on early childhood commonly have either 4-10 or 11-20 sessions, are aimed at promoting positive parenting, and involve weekly sessions lasting between 90 and 120 minutes. Similar results were obtained when considering programmes aimed at school-age children (middle childhood), pre-adolescents, and adolescents, and also for interventions targeting the family, independent of children’s age. These findings suggest that regardless of the age of the target population, there is some consistency in the duration and frequency of programme sessions, most likely in response to the identified needs of families. Considering the target population, programmes targeting at-risk families (selective population) are more common (61.4%) than are universal programmes (45.6%) or those aimed at clinical and subclinical populations (29.8%). Among programmes designed for at-risk families, the majority seek to promote positive parenting (82.8%), although a considerable proportion also aim to improve children’s physical and emotional well-being (65.7%) and to build their competences (60%). While universal programmes are less common overall, a higher percentage of them (73.1%) aims to enhance children’s physical and emotional well-being and develop their competences. Adequacy of the Mode of Delivery, Setting, and Facilitators It can be seen in Table 7 that most of the programmes are implemented face-to-face, most commonly in schools or in the offices of social services. Only a small number of programmes are available online or through a blended approach. As regards the relationship between the delivery setting and the target domain for outcomes, programmes that aim to achieve outcomes in the family domain are equally likely to be implemented in schools or social services (both 47.1%). When health is the target domain for outcomes, schools are once again the primary setting (64.3% of programmes), and in fact are used twice as often as health centres (32.1%). It seems, therefore, that whatever the target domain for outcomes, the school is the preferred setting for interventions of this kind. Table 7 Mode of Delivery, Setting, and Programme Facilitators   Note. 1Sum is 100%; 2percentage is for each category for n = 57. In terms of who is responsible for implementing the programmes, this is most commonly a psychologist, regardless of whether the programme is aimed more at prevention or intervention. Indeed, psychologists are most likely to be the lead professional in programmes with a focus on prevention (promoting positive parenting [81.8%], children’s physical and emotional well-being [70.5%], promoting children’s competences [68.2%], community development [47.7%], promoting adolescents’ social and emotional competences [43.2%], educational skills and attainment [36.4%], positive couple relationships [34.1%]), as well as those with a more interventionist aim (reducing problem behaviour in children [56.8%], reducing neglect or abusive parenting [36.4%], reducing substance use [22.7%]). Over the past two decades, initiatives to support positive parenting and promote the well-being of children and adolescents have become increasingly common in Spain. Our aim in this study was to identify and describe the characteristics of family support programmes that are currently implemented in our country, and to examine the extent to which they meet quality standards for programme formulation. One of the quality standards for programme formulation described by Özdemir et al. (in press) is the existence of a clearly defined theoretical model, and this was an inclusion criterion for consideration in the present analysis. However, although all the programmes we examined were underpinned by a theoretical model, this model was not always consistent with the key tenets of the positive parenting approach. With respect to target outcomes, for example, and in accordance with the findings of other reports (Frost et al., 2015), the programmes currently being implemented in Spain are mainly aimed at promoting parenting competences and have parents as the target population, although they also include pre-adolescents as a target group. The positive parenting approach proposes that children are competent and capable, and that the role of parents is to help them exercise their rights by providing direction and guidance appropriate to their evolving capacities. Consequently, family support programmes should, in addition to any direct impact they seek to have on parents, aim to have indirect effects on children, enhancing their competences in different areas of their development. Children and adolescents will have their own perspective on reality, and giving them a voice can bring fresh insights (Templeton et al., 2019). Indeed, as we noted in the introduction, the active participation of children and adolescents in parenting support programmes can favour positive change in the family. These third-generation programmes, in which children are given a participatory role, aim to improve functioning of the family as a system (Martín-Quintana et al., 2009), and research suggests that this allows feedback among family members regarding changes and improvements that benefit all those involved (Mateos et al., 2021). Our results here suggest that the participation of children and adolescents is an aspect yet to be fully addressed within family support programmes in Spain, insofar as few of the programmes we analysed give them an active role as representatives of the target group; this was even the case among some programmes with the stated goal of improving children’s competences. Another issue to consider is that most of the programmes analysed are aimed at at-risk families. This suggests that further efforts are needed in Spain to move toward progressive universalism (Rodrigo, 2015), whereby parenting support would be available to all families and would reflect the increasing diversity of family structures and cultural backgrounds in our country, as well as the wide range of functional needs among children today. In practical terms, this means developing family support programmes that aim not only to meet the developmental needs of children but also to improve the conditions in which families live, the ability of parents to exercise their role and responsibilities, and the relationship between families and wider society (Lacharité et al., 2005). With regard to the need for new ways of supporting families, it is worth noting that few of the Spanish programmes we analysed were available in an online format. If the goal, however, is to make support available for everybody (progressive universalism), then the development of more online family support programmes would seem to be crucial. During the recent Covid-19 pandemic, for instance, the existence of online support programmes could have played an important role in helping families adapt to lockdown. When it comes to the target population, family support programmes in Spain encompass the three types of intervention described by Canavan et al. (2016), namely universal, selective, and indicated, although they differ in the approach they take. One approach is aimed at prevention and promotion and seeks to maximize families’ strengths, with goals including improving children’s physical and emotional well-being and their competences in general, promoting adolescents’ social and emotional competences, or developing community ties. The second approach is based on a model of risk and deficit and primarily aims to reduce problem behaviours, for example, substance use among adolescents. Most of the programmes analysed fall into the second of these two categories (i.e., they are based on a model of risk and deficit), although there are now programmes aimed at building families’ strengths. This suggests that Spain is currently in a transition stage between these two models, that is, the traditional deficit-based model and the capacity-building approach inspired by the tenets of positive parenting. In our view, therefore, the progressive adoption of evidence-based programmes informed by the principles of positive parenting, together with efforts to improve the psychosocial context of families and children, could help to create a framework of protection and support services in line with what Bueno-Abad (2005) proposed. In addition to a greater emphasis on capacity building, there is also a need to develop programmes in which children and adolescents are given a participatory role as representatives of the target group. Another aspect we examined was the extent to which family support programmes in Spain meet evidence-based quality standards. One quality standard that is mentioned by various authors (Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Kumpfer & Alvarado, 2003; Özdemir et al., in press) is the existence of a programme manual so as to ensure fidelity of implementation by different practitioners and agencies. All the programmes analysed here were manualized, and the manuals included specification of the number, duration, and frequency of programme sessions, this being another quality criterion mentioned by Kumpfer and Alvarado (2003). The most common profile in the present sample was a programme involving 4-10 weekly sessions of between 90 and 120 minutes each, over a period of 2-3 months. This manualization is important given the diversity of agencies involved in implementing programmes, as well as the different levels of programme delivery and scope. It is worth noting here that most of the Spanish programmes analysed were designed to be delivered by public agencies, usually at regional level and in the social sector, reflecting the situation in most European countries, where programmes for families with higher levels of difficulties are typically provided by child welfare and social services (Molinuevo, 2013). Alongside this inter-agency and cross-sector complexity, it is also important to consider the potential diversity of professionals who may implement the programmes. Our analysis suggests that in Spain the lead professional in programmes aimed at promoting positive parenting is usually a psychologist, which probably reflects the clinical orientation that has, in our country, traditionally underpinned family services in general, and especially those aimed at high-risk families. Pedagogues, social workers, and social educators are involved in programmes that seek outcomes in other domains, although it is noteworthy that social workers and social educators appear to have limited involvement in programmes targeting domains such as the community, leisure, gender, culture, and inclusivity. Interdisciplinarity is, of course, a common feature of family interventions, and it is increasingly recognized that parenting support requires interprofessional competences. It is obviously important that those who implement family support programmes are adequately trained, and this is one of the challenges facing professionals from different disciplines as they seek to address the new realities and needs of children, adolescents, and families. In recognition of the need to identify the range of competences that underpin good practice in family support services, above and beyond those normally associated with a particular discipline, the Spanish Federation of Municipal and Provincial Authorities (FEMP), in collaboration with the Ministry of Social Rights and the 2030 Agenda, has drawn up a “Guide to interprofessional competences for promoting positive parenting: A resource for enhancing the quality of child, adolescent, and family services” (Rodrigo et al., 2021). In this respect, it is worth noting that for most of the programmes analysed in this study, any training related to their use was free to practitioners. This helps to ensure that programme deliverers will be adequately trained, which in turn increases the likelihood of fidelity of implementation, which is another important quality standard to consider (Özdemir et al., in press). In conclusion, the Spanish family support programmes analysed in this study fulfil several of the quality standards for programme formulation described by Özdemir et al. (in press). All of them were supported by a clearly defined theoretical model and were either fully or semi-manualized, including specification of the number, duration, and frequency of sessions, the latter being one of the quality criteria mentioned by Kumpfer and Alvarado (2003). In addition, the interventions are adapted to the ages and developmental stages of children, and are responsive to the needs, characteristics, and expectations of the target group. However, many of the programmes do not give children and adolescents a participatory role as representatives of the target group, and only a minority are aimed at building families’ strengths rather than being based on a model of deficit and risk. Limitations and Contributions of the Study The present study has a number of limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the sample analysed does not include all the family support programmes that currently exist in Spain, and hence the results may not be totally representative of the situation in our country. Although the experts who selected the programmes for analysis were instructed in how to apply the inclusion criteria, we cannot rule out potential bias in this respect. Second, the fact that the data collection sheets were completed by different members of the Spanish Family Support Network may have introduced a degree of heterogeneity into the process of gathering information, which could bias the conclusions drawn. Finally, our interpretation of the extent to which the programmes met different quality standards for programme formulation is inferential based on the descriptive information obtained from the data collection sheets, rather than being derived from a direct evaluation of these standards for each of the programmes analysed. Despite these limitations, we believe our results to be of considerable importance. The analysis shows that a large number of family support programmes in Spain do meet evidence-based standards in their design, and it also highlights those areas where further efforts are required. In particular, there is a need to increase the participation of children and adolescents, to further consolidate a capacity-building model of intervention, and to make family support universally available. The findings provide a platform from which to design new programmes in accordance with standards for prevention programmes, and may inform stakeholders and politicians in drawing up evidence-based public policies. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Funding: This article is based upon work from COST Action CA18123 European Family Support Network, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) www.cost.eu. Cite this article as: Bernedo, I. M., Balsells, M. A., González-Pasarín, L., & Espinosa, M. A. (2022). Evidence-Based Standards in the Design of Family Support Programmes in Spain. Psicología Educativa, 29(1), 15-23. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2022a6 References |

Cite this article as: Bernedo, I. M., Balsells, M. A., González-Pasarín, L., & Espinosa, M. A. (2023). Evidence-based Standards in the Design of Family Support Programmes in Spain. Psicolog├şa Educativa, 29(1), 15 - 23. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2022a6

Correspondence: bernedo@uma.es (I. M. Bernedo).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS