Spanish Adaptation of the TEACCH Fidelity Form

[La adaptaciĂłn al castellano del TEACCH Fidelity Form]

Verónica García Romero1, Araceli Sánchez-Raya1, 2, Carmen Corpas Reina1, and Kara A. Hume3

1Universidad de Córdoba, Spain; 2Instituto Maimónides Investigación Biomédica de Córdoba - IMIBIC, Spain; 3The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA

https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2025a17

Received 26 October 2024, Accepted 10 March 2025

Abstract

The growing prevalence of students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) poses a challenge for schools, requiring them to implement specific methodologies to respond to the difficulties these students encounter. The TEACCH system is one of the most widely used approaches to address the needs of students with ASD, although few studies have determined the effectiveness of all its components. To systematize research based on this model, a fidelity measure of the application of the methodology is key. Such a measure could provide data on the intensity of application and homogeneity with which the methodology is implemented in classrooms or schools. The aim of this paper is to offer the Spanish adaptation of a fidelity questionnaire, the TEACCH Fidelity Measure (Hume et al., 2011), a fundamental tool for assessing the effectiveness of this methodology in future research.

Resumen

El aumento del número de alumnos que padecen trastorno del espectro autista (TEA) ha supuesto un reto en los centros educativos, surgiendo la necesidad de aplicar metodologías específicas que respondan a las principales dificultades con las que se encuentra este alumnado. El sistema TEACCH es uno de los más extendidos, aunque aún contamos con pocos estudios sobre la eficacia de todos sus componentes. Una de las claves para sistematizar investigaciones que fundamenten este modelo sería la medida de la fidelidad de la aplicación de la metodología, que podría proporcionarnos datos sobre la intensidad de la aplicación y su homogeneidad en las distintas aulas o centros educativos. El objetivo de este trabajo es la adaptación al castellano de un cuestionario de fidelidad, la medida de fidelidad TEACCH (Hume et al., 2011), como herramienta fundamental para valorar la eficacia de esta metodología en futuros estudios.

Palabras clave

TEACCH, TEA, Prácticas basadas en pruebas, Fidelidad de la implementaciónKeywords

TEACCH, ASD, Evidence-based practices, Implementation fidelityCite this article as: Romero, V. G., Sánchez-Raya, A., Reina, C. C., and Hume, K. A. (2025). Spanish Adaptation of the TEACCH Fidelity Form. PsicologĂa Educativa, 31(2), 153 - 169. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2025a17

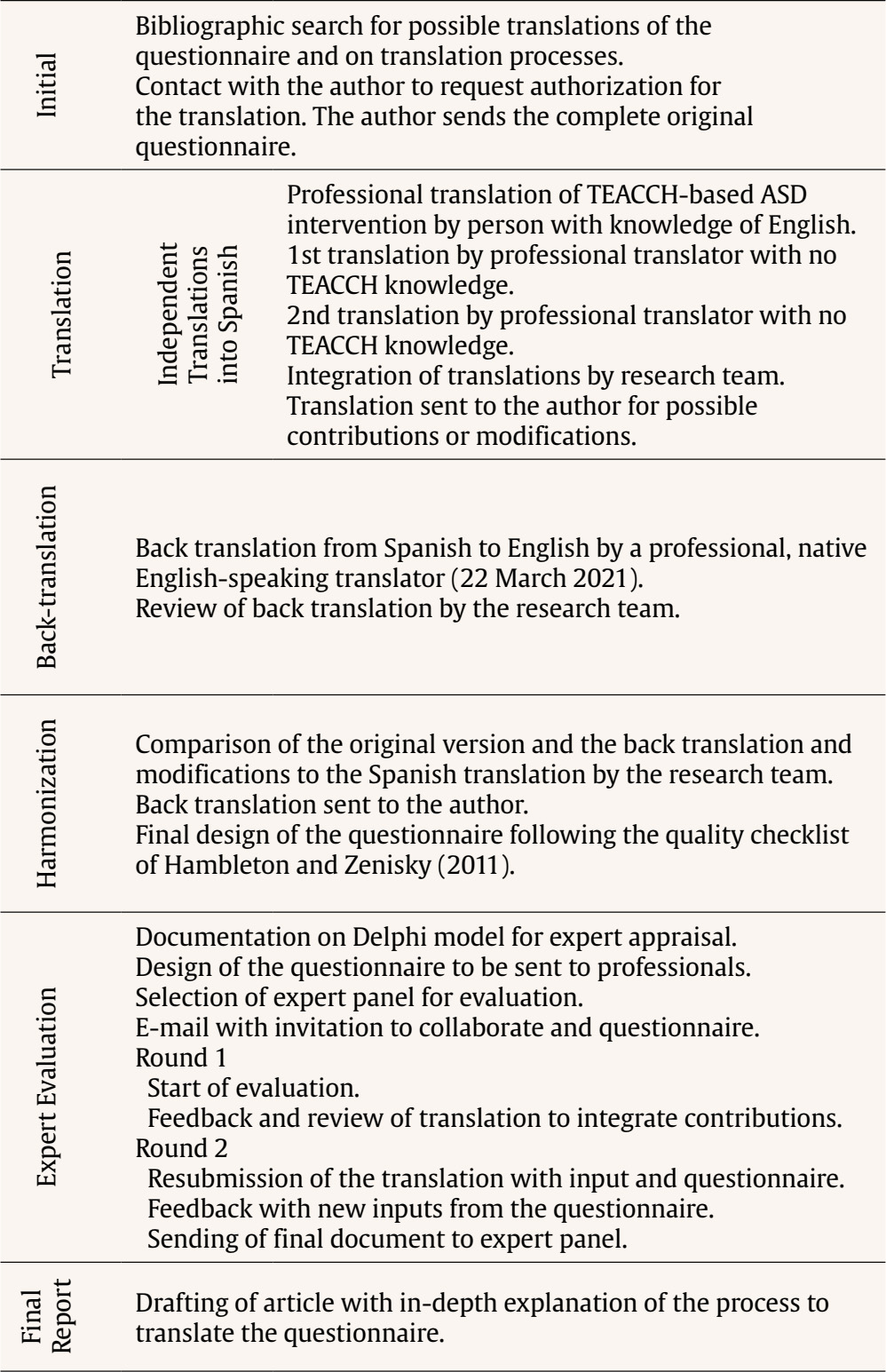

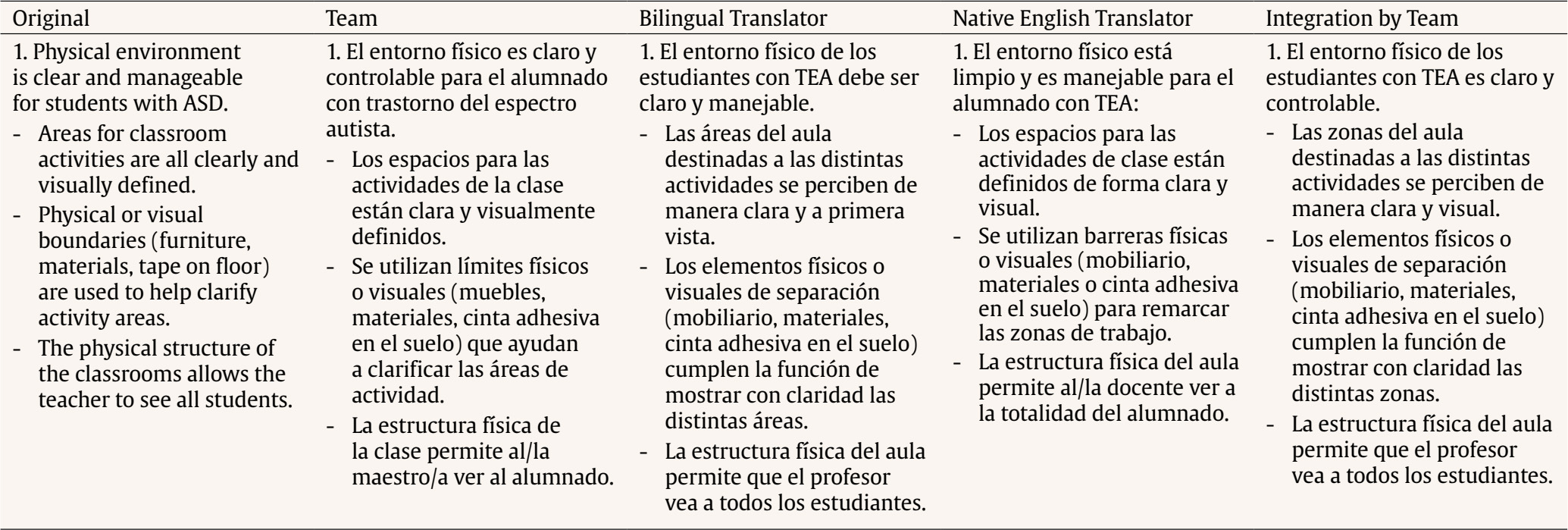

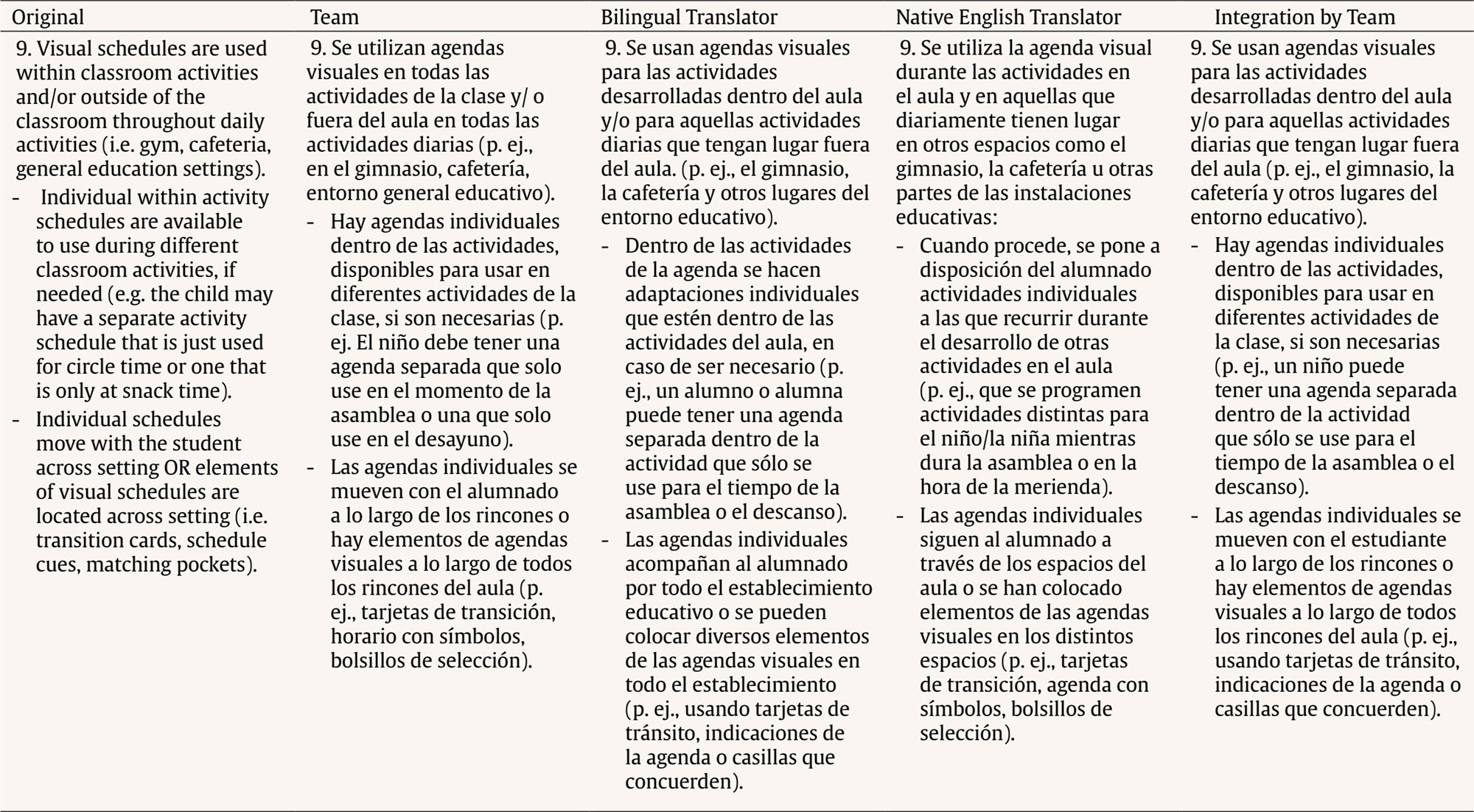

Correspondence: ed1saram@uco.es (A. Sánchez-Raya).In recent years, education systems have transformed schools into a space for teaching and learning tailored to an increasingly diverse student body. The most significant initiatives have been supported in international agreements, particularly the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Asamblea General, ONU, 2015). These initiatives have led to gradual legislative changes that promote a vision and reconceptualization of egalitarian education. In Spain, the changes introduced by Organic Law of Education [Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de diciembre, por la que se modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación, popularly known as LOMLOE] have evolved from a concept of special educational needs focused on the person to identifying and overcoming barriers that limit access to education of students in vulnerable situations. This principle is in line with the concept of inclusion outlined in the Spanish version of the Inclusion Index (Booth & Ainscow, 2000), understood as a process to increase the presence, participation, and educational success of students at risk of exclusion. Such an approach requires restructuring educational cultures, policies, and practices to respond to what occurs inside the classroom and is based on a model of social inclusion that focuses on overcoming barriers to learning and participation rather than just special educational needs. In line with this new way of conceptualizing education, it is essential to implement effective methodological practices that respond to different educational realities. In this regard, students with the autism spectrum disorder (ASD) pose a challenge for schools. As pointed out in a recent study by Confederación Autismo España, a nationwide organization of 170 member institutions that provides specialized support and services to people with ASD and their families, “educational contexts are complex environments that involve significant challenges for students with ASD” (Vidriales Fernández et al., 2021). Additionally, according to the annual report on students with special educational needs issued since the 2011-2012 academic year by the Spanish Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, the number of students with ASD (using severe developmental disorders as the reference category) have increased 216.64% in the last ten years (Confederación Autismo España, 2022). The high prevalence of students with ASD in an educational system guided by a philosophy of inclusion, such the Spanish one, has led to the need for effective methodologies addressing the specific symptoms of these students in a normalized and egalitarian context. Along these lines, the TEACCH structured teaching program (Mesibov et al., 2005) provides a series of strategies and tools to carry out interventions in students with ASD and promote their inclusion through the access to a broader curriculum (Mesibov & Howley, 2010/2003). TEACCH is a comprehensive intervention program. According to the definition of the National Research Council, these programs consist of a series of strategies to improve the core symptoms of autism (Odom et al., 2010). However, several studies have questioned the effectiveness of these models. Virués-Ortega et al. (2013) underlined the need for empirical studies of the model components as well as adequate assessment instruments. In this regard, Hume et al. (2011) designed an instrument to measure each of the components of structured teaching and assess the validity and reliability of the implementation of the instrument since, as the authors state, “If the components of the treatment are not well measured, no definitive conclusions can be drawn regarding the effects of the independent variables on the outcome measures.” (p. 2). The aim of this work is to adapt the original version of the TEACCH Fidelity Measure into Spanish (Hume et al., 2011), an instrument designed to evaluate the implementation of each of the components of structured teaching. For the Spanish adaptation of the questionnaire, the International Test Commission Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests (2nd edition) (Muñiz et al., 2013) were followed and a translation-back-translation procedure was used relying on translations by professional translators. To avoid a literal translation that might not guarantee the validity of the adapted version (as indicated in the guidelines mentioned above), a team supervised the entire process and adapted the different versions to obtain an initial model. This initial model then underwent a validation process by a panel of experts using the Delphi method, a technique that, as pointed out by López-Gómez (2018), is based on the principle of “collective intelligence.” The application of the Delphi method enriched and contributed to the adaptation process, allowing us to obtain a final instrument that is easy to understand and can be applied in the target population. The complete process to adapt the instrument is shown in Table 1. Initial Phase Prior to the translation, we made sure that no Spanish version of the TEACCH Fidelity Measure existed and carried out a literature search on processes to translate and adapt questionnaires. To comply with ethical and copyright criteria, permission was obtained from the first author to use the original questionnaire. Translation To avoid a literal translation, the first version in Spanish was elaborated by a research team of professionals with a proficient knowledge of English who intervene directly with students with ASD and were familiar with the TEACCH system. At the same time, the questionnaire was translated by two professional translators, one of them being a native English speaker. The main differences between the three translations were changes in the use of verb tenses, vocabulary specific to the field of education, as well as the specific vocabulary and descriptions used in the TEACCH instrument. The research team examined the three versions with a view to drafting a final, unified document. It should be noted that a total of 439 revisions were made prior to obtaining the final translation. To analyze the differences, equivalences, and possible errors in the various translations, comparative tables were used to provide an overall view of the work and enable a more effective analysis. Table 2 shows examples of items in each of the versions translated by professionals involved in the process and the final text after the integration phase carried out by the team. A comparison of the different versions shows that the research team tried to standardize the wording of the items by avoiding unnatural structures resulting from more literal translations. In addition, the language was adapted to the educational setting and contextualized according to the reality in which the instrument will be applied. The format of the original items was kept as much as possible, including the questionnaire’s physical appearance and length, as well as the use of punctuation, bold type, italics, and bullet points, among other aspects. In certain cases, however, some elements were modified for the sake of readability and naturalness of expression due to differences in structure and syntax between English and Spanish (Table 3). One of the most disputable aspects by the research team during the consensus process was the choice of appropriate structures or vocabulary to refer to very specific concepts of the TEACCH approach, that is, concepts describing components or original methodological strategies of structured teaching. For this purpose, it was very useful to check the literature on the TEACCH system that had been translated into Spanish (Mesibov & Howley, 2010/2003; https://teacch.com/). Finally, inclusive language was used to adequately address the gender view, which led the team to reach a consensus on the use of generic plurals in Spanish whenever possible. Back Translation A bilingual, native English-speaking back-translated the Spanish version into English, which was then analyzed by the research team. Harmonization The research team compared the original version and the back translation in detail, resulting in several changes of the Spanish version. Table 4 provides a comparative overview of the different versions. The analysis of the back translation showed that the overall meaning of each of the items had been captured. However, there were certain nuances, such as the use of clarifying adjectives and specific TEACCH concepts, which required rewording to increase item clarity and avoid any misinterpretations in item application. Finally, with the help of the checklist proposed by Hambleton and Zenisky as a reference (Muñiz et al., 2013), we obtained the final Spanish version, which was sent to the author for any contributions she considered should be made. Expert Evaluation Following a documentation process, the Delphi model was chosen as the most appropriate method of evaluation as it allows for an analysis by a panel of experts who not only make technical contributions, but also enrich the work with their expertise. In this case, given that the questionnaire items frequently refer to methodological practices exclusive to TEACCH and use specific vocabulary originally in English, the vision of professionals who have used this methodology and are familiar with the concepts is crucial in adapting the instrument to the educational reality of the target population. Two basic inclusion criteria highlighted by López-Gómez (2018) in his review on the use of the Delphi method in educational research were considered for the selection of experts: i) recognized experience in working with students with ASD and ii) knowledge of the TEACCH system. After launching the proposal via e-mail, 13 experts participated in the process and were sent a questionnaire to evaluate the adapted version of the instrument. The questionnaire (see Appendix) consisted of a 5-level Likert scale with fourteen items clustered into four dimensions (General Aspects, Item Format, Grammar and Writing, and Culture) according to Hambleton and Zenisky’s checklist (Muñiz et al., 2013). The questionnaire was also used in the harmonization phase. To facilitate feedback, a digital version of the questionnaire in Google Forms was used and sent to the panel of experts via e-mail. To determine the appropriate number of rounds of consultation, López-Gómez’s contributions (2018) were again taken into account. Finally, we opted for two rounds to prevent attrition and establish deadlines. Round 1 In the first round, we contacted the panel of experts to invite them to participate in the evaluation and explain the procedure to be followed. A total of 13 responses were obtained that included observations for each of the items. The research team analyzed each of the contributions and a new adaptation of the questionnaire in Spanish was undertaken following some general criteria and based on the consensus among experts’ responses. These criteria were determined according to the aspects assessed in Hambleton and Zenisky’s quality control list (as cited in Muñiz et al., 2013), as follows: 1. Once checked by the research team, all contributions referring to item format, grammar, and wording were included. 2. For the contributions referring to the assessment of general aspects of the questionnaire and cultural factors, the graphs generated from Google Forms were analyzed considering the percentage of responses in each category (López-Gómez, 2018). In those responses where there was a coincidence in the observations by more than one of the experts, an exhaustive analysis was carried out, leading to relevant changes. Observations made by a single expert were analyzed individually and only those that could be supported through literature sources were included. Round 2 The questionnaire in Spanish with the relevant adaptations/changes was sent back to the panel of experts through a document that included the graphs with the responses from the first round, as well as the individual observations, and they were asked to complete the evaluation questionnaire once again. In this second round, a total of 12 responses were received and the experts’ contributions were again analyzed by the research team to make the final modifications to the Spanish version of the questionnaire. Final Report The final version of the questionnaire in Spanish was sent to the panel of experts and an article describing the entire procedure was subsequently drafted. Table 5 includes data belonging to the different phases and the final report, thus providing a clear overview of the entire process and procedure as well as the final modifications. Due to the high prevalence of students with ASD in schools, it is necessary to implement effective methodologies that address the barriers to learning and participation they encounter every day. The presence of students with ASD can be reinforced by inclusive models of education in line with the political and organizational changes set out in the recommendations of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UNESCO, 2015). However, educational success and inclusion require evidence-based practices (EBP) and studies showing the efficacy in the context where such practices are intended to be implemented. The TEACCH system, which utilizes the structured teaching method to support students with ASD, is now one of the most widely used forms of educational intervention in special and non-special education schools. This system is among the so-called integrated treatment models (ITM), as it includes different components that are applied over a prolonged period of time with great intensity (Odom et al., 2010) to improve the core symptoms of ASD. Several studies have shown evidence of the efficacy of some of the TEACCH components (Abshirini et al., 2016; Fornasari et al., 2012; Hume et al., 2012; NasoudiGharehBolagh et al., 2013; Probst et al., 2010; Virués-Ortega et al., 2017). However, many of the studies available in the main bibliographic databases focus on specific populations, while structured, randomized research with large enough samples to provide evidence for all the components of the TEACCH system (i.e., as an ITM) is lacking. These studies also lack data on the fidelity of implementation of the methodology. In this line, Hume et al. (2011) highlighted the limited use of implementation fidelity measures in intervention studies, while anticipating a change given that major funding agencies have begun to require such measures as an integral component of research projects. More specifically, the authors evaluated the implementation of two instructional methods for students with ASD, including TEACCH. In response to the need for objective data on the implementation of TEACCH, an aspect that could be crucial in increasing the effectiveness of this approach, they presented the TEACCH Fidelity Measure, an instrument to assess implementation fidelity. As already indicated, although many studies have collected evidence on specific components of TEACCH, the most recent guidelines and reports on the evaluation of EBP continue to point to the intensity of implementation as a determining factor to gain a better understanding of positive outcomes in students (Reviriego et al., 2022; Soetikno & Marat, 2021). In short, research on EBP in students with ASD has not yet provided relevant information on the fidelity of implementation of specialized practices, although there is evidence of the impact of these practices on outcomes in individuals with ASD (Charman et al., 2011). Therefore, given the importance of these fidelity measurement tools, the shortage of studies on TEACCH effectiveness, and the evidence that it is one of the most recommended and widespread methodologies for working with students with ASD, we considered that it was of great importance to adapt the TEACCH Fidelity Measure (Hume et al., 2011) to Spanish, a language in which studies are lacking despite the widespread use of this method. The process has been complex, as the specificity of the methodology and the shortage of references in Spanish has limited our ability to compare the translation of specific TEACCH concepts. Therefore, we decided to rely on a panel of experts in the field, which has been key in reaching consensus on the choice of terminology and wording of concepts that most closely matched the meaning of the original document. The TEACCH Fidelity Measure in Spanish is an instrument that can provide crucial information to avoid an “implementation gap” that may lead to a mismatch between what the theory proposes and what is actually implemented in practice (Escorcia et al., 2021). Cite this article as: García Romero, V., Sánchez-Raya, A., Corpas Reina, C., & Hume, K. A. (2025). Spanish adaptation of the TEACCH fidelity form. Psicología Educativa, 31(2) 153-169. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2025a17 References |

Cite this article as: Romero, V. G., Sánchez-Raya, A., Reina, C. C., and Hume, K. A. (2025). Spanish Adaptation of the TEACCH Fidelity Form. PsicologĂa Educativa, 31(2), 153 - 169. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2025a17

Correspondence: ed1saram@uco.es (A. Sánchez-Raya).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS