Long-term Effects of the Loss of Stimulation during the COVID-19 Pandemic on Preschoolers’ Cognitive Development

[Los efectos a largo plazo de la pérdida de estimulación en el desarrollo cognitivo infantil durante la pandemia de COVID-19]

David Muñez1, Josetxu Orrantia2, Rosario Sanchez2, & Paula Muñoz2

1Centre for Research in Child Development, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore; 2University of Salamanca, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a1

Received 14 October 2024, Accepted 21 April 2025

Abstract

This study investigates the long-term effects of the loss of regular in-person preschool stimulation during the COVID-19 pandemic on various cognitive aspects in 4- and 5- year-old children in Spain (N = 307). Specifically, the study examines whether this disruption differentially affected early numeracy and literacy skills, working memory, and non-verbal reasoning and whether the impact varies as a function of the child’s developmental stage. Results reveal that children in the post-COVID cohorts show delays across both academic and non-academic domains. Younger children, who experienced the disruption during their first year of preschool, exhibit more pronounced deficits. These findings suggest that the pandemic’s disruption to preschool routines, including periods of school closures, remote learning, and atypical in-person stimulation, negatively impacted cognitive development, particularly for those at earlier developmental stages. The findings highlight the importance of regular in-person preschool stimulation for young children’s cognitive development.

Resumen

El presente estudio analiza los efectos a largo plazo de la pérdida de estimulación presencial habitual en Educación Infantil durante la pandemia de COVID-19 sobre diversos aspectos cognitivos en niños y niñas de 4 y 5 años en España (N = 307). En particular, se examina si dicha interrupción afectó de forma diferencial las habilidades tempranas de alfabetización y competencia matemática, la memoria de trabajo y el razonamiento no verbal, y si el impacto varió en función de la etapa del desarrollo infantil. Los resultados muestran que los niños y niñas pertenecientes a las cohortes posteriores a la pandemia presentan retrasos tanto en dominios académicos como no académicos. Aquellos que experimentaron la interrupción durante su primer año de escolarización en Educación Infantil presentan déficits más marcados. Estos hallazgos sugieren que la disrupción de las rutinas en educación infantil—incluidos los cierres de los centros, la enseñanza a distancia y una estimulación presencial atípica—afectó negativamente al desarrollo cognitivo, especialmente en los niveles más iniciales del desarrollo. Los resultados subrayan la relevancia de la estimulación presencial regular en Educación Infantil para favorecer el desarrollo cognitivo en la primera infancia.

Palabras clave

Educación Infantil, Alfabetización temprana, Habilidades numéricas tempranas, Conciencia fonológica, Pandemia de Covid-19Keywords

Early child education, Early literacy, Early number abilities, Phonological awareness, Covid-19 pandemicCite this article as: Muñez, D., Orrantia, J., Sanchez, R., & Muñoz, P. (2026). Long-term Effects of the Loss of Stimulation during the COVID-19 Pandemic on Preschoolers’ Cognitive Development. PsicologĂa Educativa, 32, Article e260444. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a1

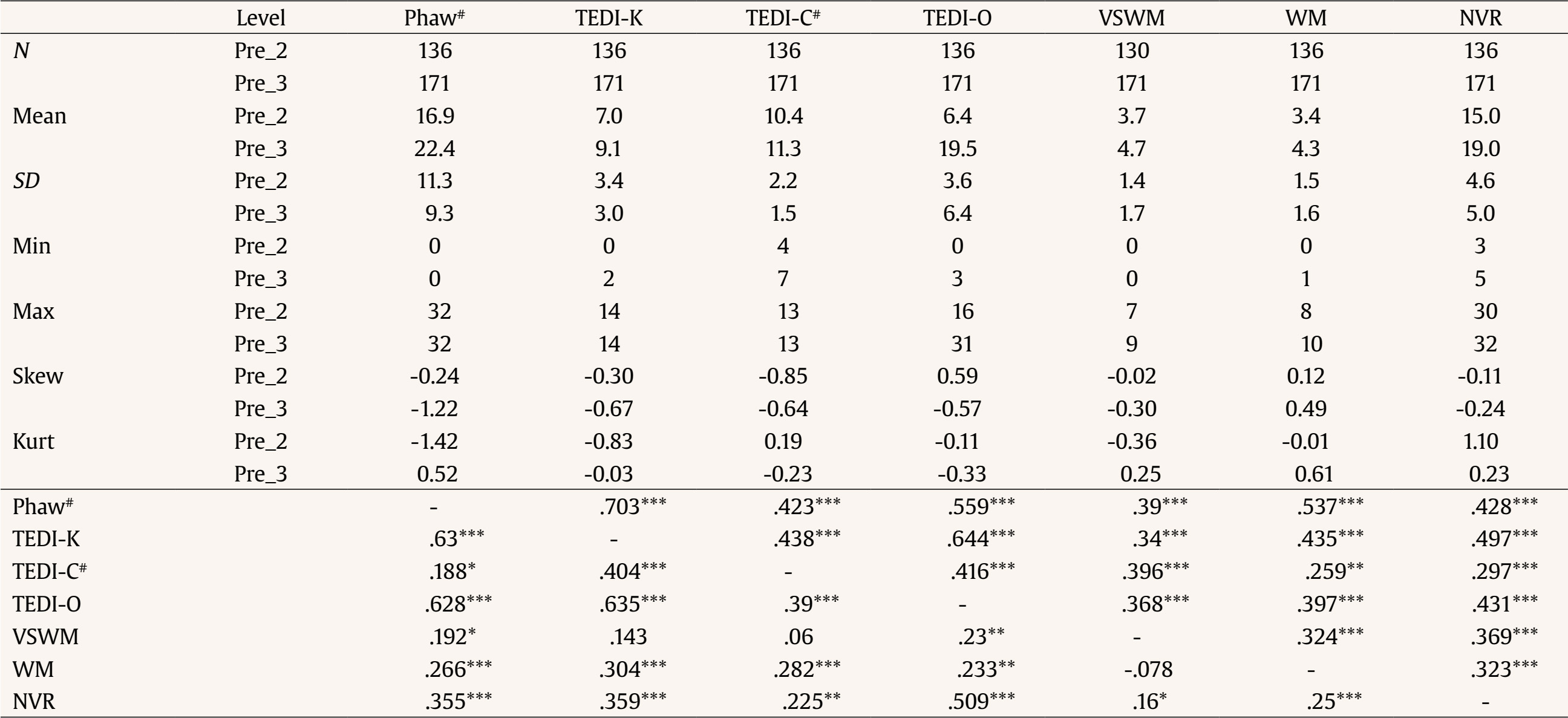

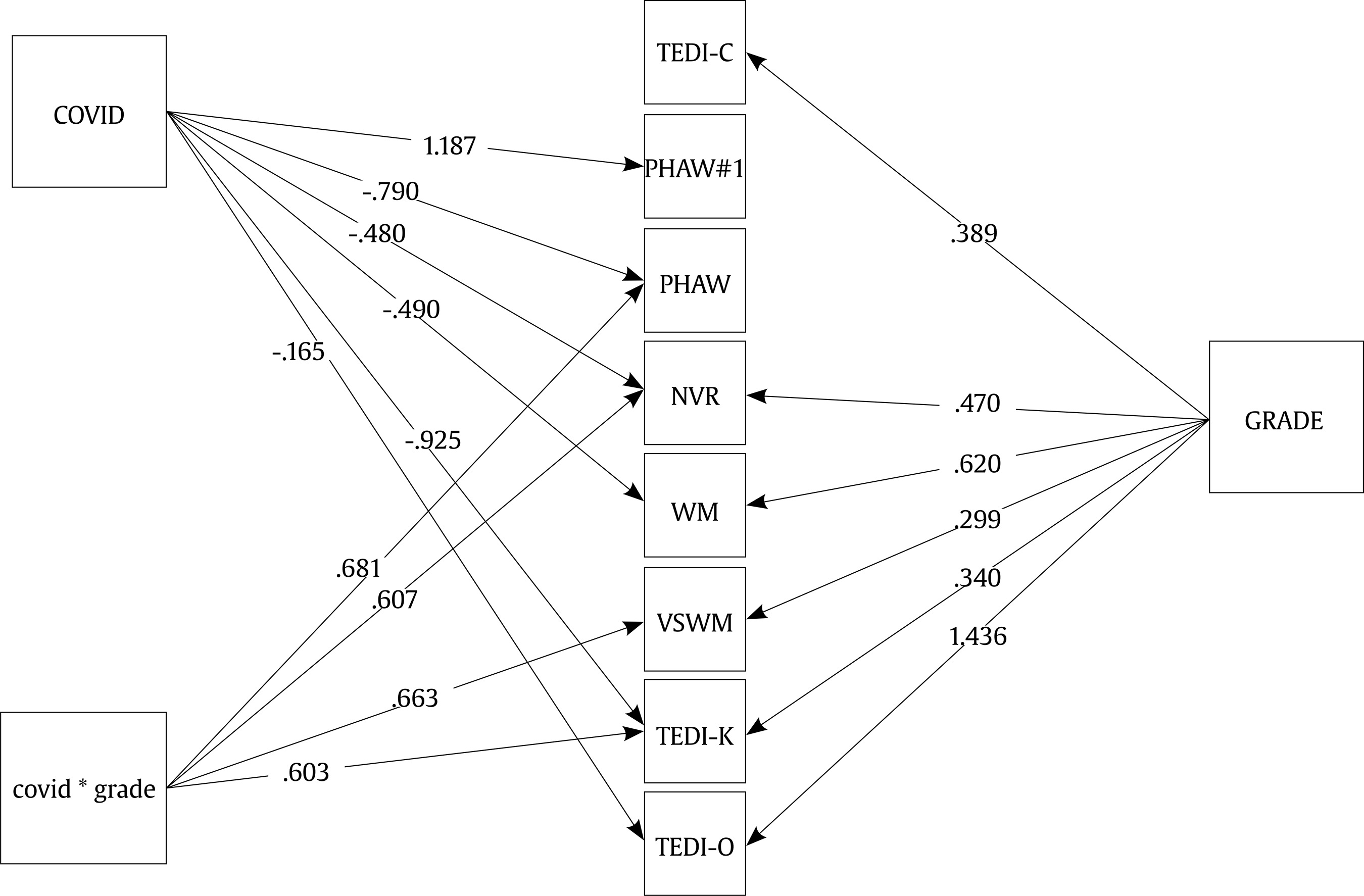

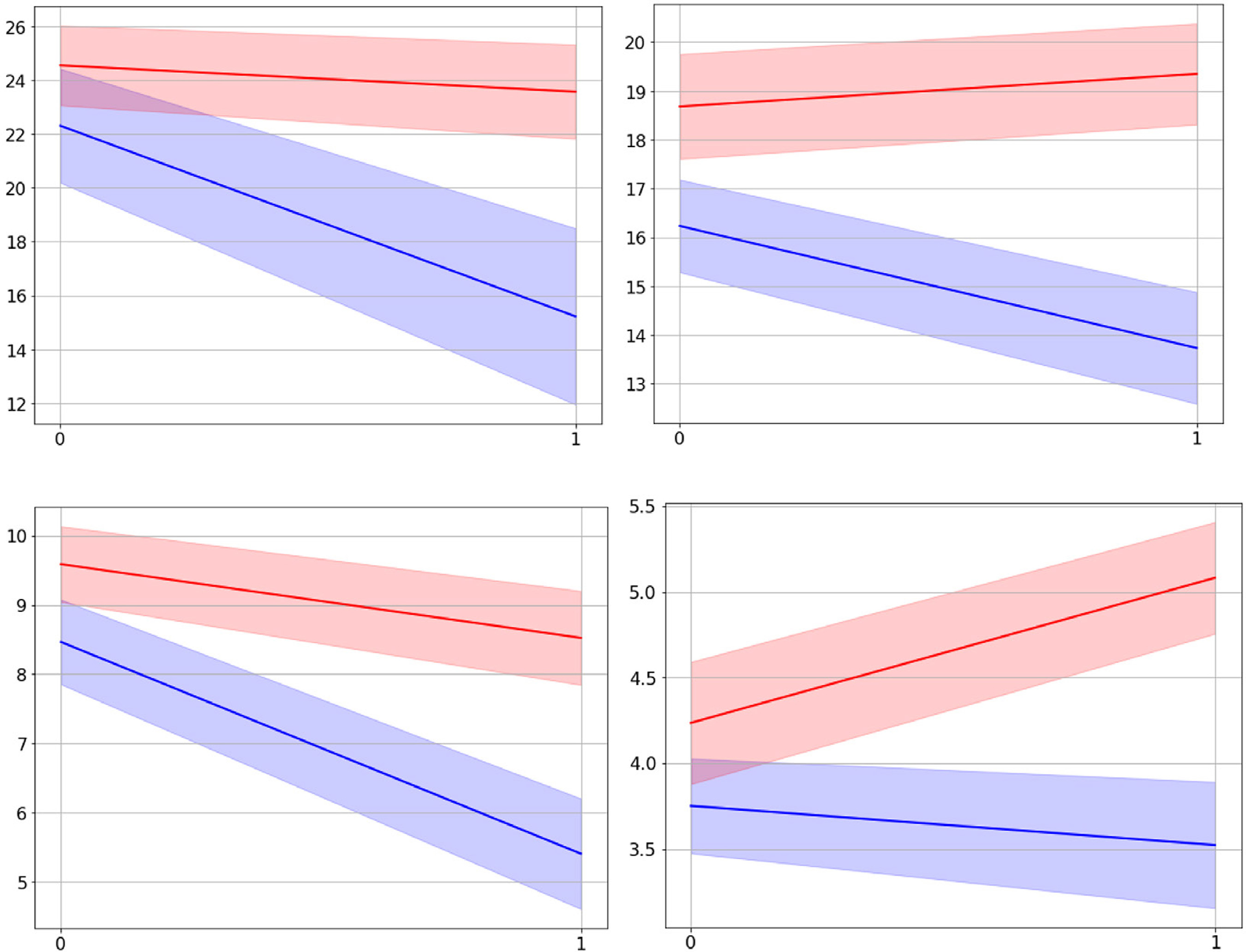

Correspondence: orrantia@usal.es (J. Orrantia).The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted various aspects of young children’s lives, including their access to regular in-person preschool stimulation. In many industrialized countries, school closures and remote learning during the pandemic’s peak were followed by an extended period of atypical in-person preschool stimulation. This atypical stimulation included additional school closures and health and safety measures that altered preschool routines and the way teachers contributed to children’s development. This disruption in regular or typical in-person preschool stimulation due to the pandemic lasted for approximately 12-15 months and raised concerns about its potential impact on young children’s development. However, due to a lack of normative and standardized data during the preschool years, these concerns remain unaddressed. The few studies investigating the impact on young children have relied on indirect assessments from parents and caregivers, which do not provide clear evidence regarding whether the loss of in-person preschool stimulation resulted in developmental delays in post-COVID cohorts. In this study, we focus on 4- and 5-year-olds who experienced the loss of regular in-person preschool stimulation due to the COVID-19 pandemic during their first and second years of preschool (at ages 3 and 4, respectively). Specifically, we use direct assessments to investigate i) whether that loss of regular preschool stimulation affected the development of various cognitive aspects similarly (early numeracy and literacy skills, working memory, and non-verbal reasoning) and ii) whether the impact of that loss (if any) varied as a function of the child’s developmental stage. Young Children’s Cognitive Development over the Preschool Years: A Flourishing Garden Over the preschool years, a child’s development is characterized by rapid cognitive growth across various domains. For instance, between 3 and 5 years, children show significant progress in number recognition and counting, developing an understanding of cardinal numbers (the quantity represented by a numeral) and ordinal numbers (the order of objects in a sequence). They learn to count objects accurately, even in sets up to 10 (Carey, 1992; Clements & Sarama, 2012), and develop the ability to compare quantities, understanding concepts like “more”, “less”, and “equal” (Starkey & Cooper, 1980). They also start to grasp simple addition and subtraction concepts, particularly within the context of concrete objects (Baroody, 1987, 2017). For instance, they can solve simple problems like “If you have two marshmallows and eat one, how many are left?”. The foundations of literacy are also laid during the preschool years. Children demonstrate growth in phonological processing, developing an understanding of the sound structure of language. They can identify rhyming words, isolate sounds in words, and manipulate sounds to create new words (Lundberg et al., 1988; Tunmer & Nicholson, 2011). Children develop the skills necessary for decoding and encoding, such as letter recognition and letter-sound correspondence (Ehri, 1991; Treiman et al., 1998). They also begin to recognize print in their environment and understand its purpose. For instance, children start to experiment with writing, creating their own scribbles and letter-like symbols (Clay, 1993). Besides numeracy and literacy, other cognitive domains such as the child’s working memory and the ability to reason spatially develop substantially during the preschool years. For instance, Gathercole et al. (2004) found that the developmental functions for measures associated with the components of Baddeley and Hitch’s (1974) working memory model—phonological loop, visuo-spatial sketchpad, and central executive— showed linear increases in performance from 4 years through to adolescence. A child’s spatial reasoning skills also undergo substantial changes over the preschool years (Newcombe & Huttenlocher, 2000). Children can identify increasingly complex patterns and solve puzzles. Notably, the domains mentioned above exhibit substantial developmental overlap during the preschool years, with skills feeding into each other. For instance, findings from correlational studies suggest that about 40-50% of the variance in young children’s reading and math is shared, with some authors uncovering bi-directional associations that span the preschool years (Bailey et al., 2020). There is also evidence of associations between academic and non-academic domains. For instance, phonological working memory is an integral part of phonological processing models—a robust predictor of later reading success (Anthony et al., 2007). Working memory is also associated with young children’s mathematics. Miller-Cotto & Byrnes (2020) found that working memory capacity was significantly correlated with children’s math growth during the preschool years. Studies that have considered children in the early grades of formal school have underscored the bi-directional nature of this association (Kahl et al., 2022). The Value of Preschool Stimulation to Support Young Children’s Cognitive Development: A Booster of Cognitive Development Providing stimulating environments that encourage exploration, experimentation, and practice in the domains mentioned above is crucial for supporting optimal development (Cantor et al., 2021). In most industrialized countries, policy recommendations are translated into educational guidelines that highlight the significance of providing appropriate stimulation for foundational skills. For example, when it comes to young children’s mathematics, activities that involve manipulating objects and tokens when reciting the count sequence promote the understanding of counting (one-to-one correspondence and stable order) and cardinality understanding (Ginsburg et al., 2008). In the literacy domain, reading aloud and singing songs are among the activities that contribute to young children’s development of literacy skills (Baroody & Diamond, 2016). There is robust evidence of the positive impact of preschool stimulation on children’s development of numeracy and literacy skills (Vandell et al., 2010; for a narrative review, see Melhuish et al., 2015). For example, Barnett and Lamy (2006) found that children who attended preschool for either one or two years demonstrated better mathematical skills than those who did not have exposure to early childhood education and care. In a large-scale study involving over 2,500 children, Melhuish et al. (2008) observed a positive association between the number of months spent in preschool and children’s progress in numeracy during the preschool period (see also Frede et al., 2007). Preschool attendance is also associated with the development of literacy skills. Frede et al. (2007) found that children who attended preschool had significantly higher scores in early literacy compared to those who did not, with effect sizes of 0.18 SD for children with one year of preschool experience and 0.38 SD for those who attended preschool for two years. Studies examining the effects of preschool absenteeism have also provided evidence for the positive role of regular in-person preschool stimulation. Frequent or prolonged absences from preschool can negatively impact academic progress, leading to difficulties in foundational skills such as early literacy and numeracy (Ansari & Purtell, 2017). Less is known about the impact of regular preschool stimulation on the development of non-academic aspects, despite policy efforts that highlight the holistic development of children. In contrast to numeracy and literacy skills, which usually develop as a function of the availability of learning opportunities and have well-established curricula and developmental milestones, non-academic aspects such as the child’s working memory capacity and reasoning skills develop in the background. Thus, such development may be considered incidental to some extent. As mentioned above, the mutual associations between academic and non-academic skills suggest that, for instance, reading and math activities contribute to stimulating the development of other cognitive aspects such as working memory and the child’s reasoning skills. COVID-19 Pandemic and Children’s Cognitive Development Recent meta-analyses have shown significant decreases in achievement across a wide range of school grades and academic domains among student cohorts affected by school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic (Betthäuser et al., 2023; König & Frey, 2022). For instance, Schult et al. (2022) found lower math and reading performance among students in 2020 compared to previous years in German schools. However, extant meta-analyses also reveal substantial discrepancies. Many studies have reported no learning losses during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, Lerkkanen et al. (2023), with a sample of Grade 4 children in Finland, found no impact on mathematics. Similarly, Gore et al. (2021) found no effects on math and reading achievement with a sample of Grade 3 and 4 students in Australia. These mixed findings are summarized in existing literature syntheses, which highlight the substantial variability in the effect of remote learning and school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s academic achievement. For instance, Hammerstein et al. (2021) found a negative effect of school closures on students’ mathematics and reading achievement and identified age as a significant moderator—younger children were more negatively affected. Tomasik et al. (2020) found that primary school children experienced larger learning losses compared to secondary school children (-0.37 SD vs. -0.10 SD, respectively). Similarly, in a recent large-scale study with 1st-to-8th-grade Hungarian children, Molnár and Hermann (2023) found that learning losses in mathematics were larger in younger children (approximately -0.21 SD) compared to older students (approximately -0.08 SD). It is suggested that younger children rely more on cognitive scaffolding during instruction, as their self-regulated learning capabilities may not be as developed (Tomasik et al., 2020), making the shift to remote teaching and learning during the pandemic more challenging for teachers and parents of younger students (Timmons et al., 2021). Notably, fewer studies have investigated whether learning losses were observed in preschool children despite authors underscoring the challenges of remote learning with young children (Bassok et al., 2021). As far as we know, only Lynch et al. (2023), using remote assessments, have provided detailed information on the effect of the loss of in-person preschool stimulation during the pandemic on children’s executive function, early literacy, and numeracy learning. They found that 3-to-5-year-olds who experienced such loss showed gains in all domains (from fall to spring in the year of the pandemic). Furthermore, they found that gains in oral counting, number naming, quantity comparison, and executive functions were in line with those of a norming sample. The Current Study The review of the literature reveals that the majority of studies examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s cognitive development—due to school closures and remote learning—have focused on school-age children and academic skills such as math and reading. This is mainly due to the availability of standardized data and year-to-year assessments. Less is known about the effects of the pandemic on younger children and non-academic skills. This lack of research is noteworthy because accumulating evidence suggests that differences between pre- and post-COVID cohorts may be more significant for younger children. Remote (online) learning experiences during the pandemic were particularly challenging for young children, who primarily learn through hands-on experiences and close interactions with peers and caring adults (Feldman, 2019). To our knowledge, only Lynch et al. (2023) have directly investigated the impact of the loss of in-person preschool stimulation during the COVID-19 pandemic adopting an integrative approach that considered various academic and non-academic skills (oral counting, number naming, quantity comparison, and executive functions—working memory, inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility). However, there are some aspects that warrant further research. Firstly, Lynch et al.’s study focused on a predominantly low-income sample, limiting our understanding of the generalizability of (null) effects to a broader context. Studies with school-age children have found that socioeconomic status (SES) moderates the disparities between pre- and post-COVID cohorts. For example, Gore et al. (2021) found learning losses of -0.16 SD for children from schools with low SES, while children from schools with medium SES experienced learning gains of 0.15 SD. Secondly, Lynch et al.’s study aggregated data from 3- to 5-year-olds, hence, neglecting the fact that they may have different self-regulated learning capabilities when it comes to scaffolding their learning at home. Arguably, 5-year-olds are more independent than 3-year-olds and have better self-regulation and executive functions, which may affect their level of engagement with remote (online) learning. And thirdly, the study investigated short-term effects like those that can be observed because of summer-learning losses. Therefore, it remains unknown whether the prolonged effect of school closures and atypical in-person preschool stimulation experienced by young children during the COVID-19 pandemic—spanning approximately 12-15 months—affected their development. Because of the protracted development of foundational skills in preschool children, the effect of learning losses may not be evident in the short term. In the current study, we aim to provide a nuanced understanding of the impact of the loss of regular in-person preschool stimulation during the COVID-19 pandemic on young children’s development (RQ1). To this end, we focus on a range of early numeracy and emerging literacy skills that develop at different stages between the ages of 3 and 5—enumeration skills, knowledge of the number-word sequence (count sequence), single-digit addition and subtraction, and phonological awareness. Furthermore, we consider non-academic aspects that develop more incidentally than the skills mentioned above—working memory and non-verbal reasoning. We also examine whether the impact of that loss was greater for younger children (RQ2). Thus, we focus on children who experienced such loss during the first and second years of preschool (when children were 3- and 4-years old in the context of the current study). It is important to note that the effects we investigate in this study (differences between pre- and post-COVID cohorts) are indeed long-term effects, estimated at least one year after the beginning of the pandemic—children were tested during their second and third year of preschool (when they were 4- and 5-years old). This long-term effect includes periods of school closures and remote learning for three months (between March and June 2020), a summer break (June-September 2020), seven months of “atypical” in-person preschool stimulation (between September 2020 and April 2021), and one month of regular in-person stimulation. Sample Data for the current study were drawn from a large-scale cross-sequential (multi-cohort) study exploring the development of academic skills in young children. Participants were 312 children attending Preschool 2 and 3 (149 females; Mage= 64 months, SDage= 7.1; 138 Preschool 2 children—4-year-olds). Children were recruited from two schools in a mid-size city in the west of Spain. Socio-economic status (SES) was not available for individual children, but both the information provided by school administrators and the central location of the schools within the city suggest that schools served a medium-SES area. Note that, infant school—or preschool— corresponds to the three years before children enter formal education in Spain (Preschool 1 to 3) and follows the school calendar (September to June). Although preschool education is not compulsory, Spain has nearly full enrolment—97% of four-year-olds (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD, 2017]). For the current study, we selected all cohorts for which the loss of preschool stimulation due to the COVID-19 pandemic occurred when children were in either Preschool 1 or Preschool 2. These children were tested when they were 4 and 5 years old, respectively—Preschool 2 and 3). Then, we randomly drawn an age-matched sample with children from pre-COVID cohorts. This resulted in four distinct groups. The contribution of each group to the data for the current study can be found in Table 1. All children were tested in May. Children were tested in their respective preschools in a separate room. Testing per child took approximately 1.5 hours, split over two to three sessions with no more than one session per day (in the current study, we only consider a subset of tasks). The percentage of missing data ranged between 0 and 2 percent. School closure protocols varied across Spain under the guidance of provincial/territorial health authorities. In the context of the current study, school closures (and remote learning) started in mid-March 2020 until the end of the academic year (June 2020). After the summer break, the gradual reopening of schools (from September 2020 until April 2021) was characterized by the implementation of health measures that involved adjusting preschool routines—“new normal” period. During the “new normal” period, in-person preschool activities were modified to ensure health and safety. Measures included reducing group sizes, maintaining physical distancing, and enforcing mask-wearing. Additionally, activities like singing were restricted to minimize potential health risks. During this period, there were preschool and class closures owing to the spread of COVID-19. From April 2021 until the end of the academic year (June 2021), regular preschool routines were implemented. Thus, excluding holidays, post-COVID cohorts in the current study experienced 3 months of loss of in-person preschool stimulation (remote learning) and 7 months of atypical in-person preschool stimulation. Measures All measures were paper-based. Early Numeracy Skills: Knowledge of Number-Word Sequence, Counting, and Basic Addition and Subtraction We used three subtests of the standardized assessment TEDI-MATH to assess the child’s knowledge of counting sequence, counting skills, and single-digit arithmetic. The description of the items in each subtest may be found in the Supplementary material. Raw scores were used in analyses. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for a normative sample with similarly-aged children from the same country are .87, .84, and .94, for the subtests measuring counting, knowledge of number sequence, and single-digit arithmetic skills, respectively. Emergent Literacy Skills: Phonological Awareness We used a phoneme isolation task as Caravolas et al.’s (2012). Children were presented with four blocks of eight nonword items. In the first two blocks, children isolated and pronounced the initial phoneme of consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) or consonant-consonant-vowel-consonant (CCVC) syllables. In the last two blocks, children were tasked to isolate and pronounce the final phoneme of CVC or the final consonants of CCVC stimuli. Testing was discontinued after four consecutive errors in a block. The dependent measure was the total number of correct responses. A low score indicates low phonological awareness. Corrective feedback was given on the first 2 items. In the current sample, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .97. Non-academic Skills: Working Memory and Non-verbal Reasoning Non-verbal Reasoning. We used Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices. It comprised three sets of 12 items (Sets A, AB, and B). Within each set, items were arranged in order of increasing difficulty. The administration of each set was terminated when four consecutive incorrect responses were made. The dependent measure was the total number of correct responses across all three sets. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for a normative sample with similarly aged children from the same country is .86. Working Memory. We used the Forward and Backward Digit Recall tasks from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) and the Forward and Backward Tapping tasks of the Corsi Block-Tapping test. These tasks are thought to assess three distinct components of Baddeley and Hitch’s (1974) working memory model—phonological loop, visuospatial sketchpad, and central executive. For the current study, only measures of the visuospatial sketchpad (Forward Tapping task) and phonological loop (Forward Digit Recall task) are considered. This is because children in our study showed very poor performance on tasks tapping onto the central executive (Backward Digit Recall and Backward Tapping tasks) which challenges assessments of internal consistency—i.e., more than 70 children did not pass the initial 2-span. In the Forward Digit Recall task, children listened to a series of numbers (e.g., 7, 3) and recalled the numbers in order (e.g., 7, 3). The examiner recorded the children’s responses as correct or incorrect. The task consisted of seven experimental blocks (two trials each), which progressed from a block with two numbers to a block with eight numbers. The dependent measure was the total number of correct trials. The split-half reliability for a normative sample with similarly-aged children from the same country is .75. The Corsi block-tapping test (forward) consisted of a set of ten 3x3 cm cubes arranged irregularly on a board with a numbered side that only the research assistant could see. The research assistant tapped the cubes in a sequence and children were required to reproduce the sequence in the same order immediately after the demonstration. One point per correct sequence was awarded. The sequences varied in length from two to seven blocks, with two sequences per length. The task continued until a maximum sequence of seven cubes was reached or until children failed two out of three attempts per sequence length. The maximum number of correct sequences was used in analyses. Because of the stop rule, consistency was estimated with items that were endorsed by at least 70 children. McDonald’s omega coefficient for the forward task was .75. Analytical Approach First, within each age group, multivariate outliers were identified by computing Mahalanobis D2 values. Cases with D2 probability values < .001 were removed. Then, skewness and kurtosis values for each measure were computed. On measures with values above 1, cases with z-scores above or below 3SD from the mean were removed. A total of 5 children were removed from all subsequent analyses. Mardia’s multivariate normality test was significant, indicating non-normality. To address the aims of the current study, we formulated a path model in which loss of regular in-person preschool stimulation during the COVID-19 pandemic (COVID: pre-COVID [0] vs. post-COVID [1]), grade (Preschool 2 [0] vs. Preschool 3 [1], and the interaction between COVID and grade served as predictors of all cognitive measures (yi = βo + β1COVIDi + β2grade + β3COVID * grade + ϵi). Because some skills are naturally skewed over development—for instance, phonological awareness starts developing in 3-4-year-olds as children get familiar with reading words—, we specified a censored regression for variables that showed more than 25% of observations at any end of the distribution (suggesting ceiling or floor effects). Note that floor effects may be due to the loss of regular in-person preschool stimulation, hence, it is important to retain those variables in analyses. In the current study, phonological awareness and a child’s enumeration skills showed censored distributions from below and above, respectively. For enumeration skills, we specified a censored-normal (Tobit) regression. Thus, yi in the equation described above is an unobserved latent variable where yi = max(0, yi). Regarding phonological awareness, we identified a large proportion of zeros, suggesting a censored-inflated distribution1. Thus, the regression involved a mixture of two latent classes—a logistic regression describing the probability of being in class 0 (scoring zero)—and a censored-normal model for children in class 1 (scoring more than zero). All descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were estimated using Mplus v.8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) was used because the percentage of missing data was small. FIML parameters are unbiased and efficient under MAR (missing at random)—including the more stringent MCAR (missing completely at random) condition. Furthermore, we used a robust maximum likelihood estimator (MLR), with standard errors that are robust to non-normality and non-independence of observations. Note that this estimator is also appropriate in cases of heteroscedasticity, which is likely in the context of the current study. From a theoretical point of view, regular in-person preschool stimulation may decrease the spread of the distribution of scores (i.e., pre- and post-COVID cohorts may show different variances). Descriptive and Correlational Analyses Descriptive statistics and bi-variate correlations (by grade) are presented in Table 2. Table 2 Descriptive Statistics (top) and Pearson Correlations (below diagonal = Preschool 3)   Note. Skew = skewness; Kurt = kurtosis; Phaw = phonological awareness; TEDI-K = knowledge of number-word sequence; TEDI-C = counting skills; TEDI-O = single-digit arithmetic; VSWM = visuospatial working memory; WM = working memory; NVR = non-verbal reasoning. xxx indicates a censored variable. *p < .05, * p < .01, ***p < .001. Overall, there was overlap among measures, although the magnitude of associations suggested that each variable was substantively distinct. The pattern of correlations was similar for both grades. Only the correlations with visuospatial working memory differed across age groups, with older children showing weaker associations. Indeed, no association with knowledge of the count sequence and enumeration was found. The Effect of Loss of Regular In-person Preschool Stimulation during the COVID-19 Pandemic The parameter estimates of the path model can be found in Figure 1 (unstandardized estimates are reported in Supplementary Material; Table S2). The effect sizes reported in Figure 1 reflect differences, in standard deviations, across levels of the independent variable. Across measures (except phonological awareness), 5-year-olds showed higher scores than 4-year-olds. The effect sizes were in the moderate range—except that corresponding to single-digit arithmetic, which was equivalent to about 1.5 standard deviations. This reflects the fact that single-digit arithmetic is mainly introduced in Preschool 3 when children turn 5 years old. Figure 1 STDY Standardized Effects in the Path Model (only significant paths are shown).   Note. Phaw = phonological awareness; Phawxxx1 = indicates likelihood of being in class zero (scoring zero); TEDI-K = knowledge of number-word sequence; TEDI-C = counting skills; TEDI-O = single-digit arithmetic; VSWM = visuospatial working memory; WM = working memory; NVR = non-verbal reasoning. The loss of regular in-person preschool stimulation due to the COVID-19 pandemic affected the development of both non-academic and academic domains. The negative paths from the variable COVID indicate that children in post-COVID cohorts performed worse in phonological awareness, non-verbal reasoning, counting sequence knowledge, and working memory. There was also a slight decline in single-digit arithmetic skills (although this effect was very small). Note that the interpretation of the path between COVID and PHAWxxx1 is different. The positive estimate indicates that children in post-COVID cohorts were more likely to exhibit a lack of phonological awareness (being in class zero). The model-implied probability of being in class zero for children in post-COVID cohorts was .25 and .10 for 4- and 5-year-olds, respectively. The corresponding probabilities for children in pre-COVID cohorts were not substantially different from zero. The significant paths from the interaction term to phonological awareness, non-verbal reasoning, and knowledge of count sequence indicate that the negative effect of the loss of in-person preschool stimulation varied as a function of grade. The positive coefficients indicate that the negative impact is attenuated for older children. In other words, the differences between pre- and post-COVID cohorts were smaller for 5-year olds who experienced such loss when they were in Preschool 2 than for 4-year olds who experienced such loss at earlier stages in development. These interactions are depicted in Figure 2. It can be observed that the negative effect of loss of regular preschool stimulation for phonological awareness, non-verbal reasoning, and knowledge of the count sequence was only evident for younger children who experienced such loss when they were 3 years old. The positive path from the interaction term to visuospatial working memory indicates that differences between 4- and 5-year-olds increased in post-COVID cohorts. The corresponding plot in Figure 2 (bottom right), shows that the “positive” effect of that loss of regular preschool stimulation was only observed in older children. Figure 2 Mean and 95% CI of Interaction between COVID (x-axis; 0 = pre-COVID) and Grade (red line denotes 5-year olds).   From top left to bottom right: phonological awareness, non-verbal reasoning, knowledge of count sequence, and visuo-spatial working memory. We investigated whether the loss of regular in-person preschool stimulation due to the COVID-19 pandemic affected the development of various cognitive aspects (early numeracy and literacy skills, working memory, and non-verbal reasoning) and whether the impact of that loss (if any) varied as a function of the child’s developmental stage. In the current study, such loss related to long-term effects—about one year of atypical preschool stimulation that included periods of remote learning. Effect of Loss of Regular In-person Preschool Stimulation on Children’s Development We found evidence that children in post-COVID cohorts showed a delay in academic skills that are the focus of preschool curricula (knowledge of the count sequence and phonological awareness; note that the effect on single-digit arithmetic was very small). These findings extend those of studies that have focused on school-age children. Learning losses in reading and mathematics achievement have been typically found for post-COVID cohorts in early grades of formal school (Hammerstein et al., 2021; Tomasik et al., 2020). Although there are many potential interpretations regarding why such learning losses were observed, the most feasible explanation is that the extraordinary circumstances that involved the COVID-19 pandemic posed constraints to how parents and teachers supported young children’s development. For instance, studies that have investigated how parents and early childhood education (ECE) teachers coped with challenges associated with young children’s remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic have underscored that both parents and children struggled with remote learning and that home routines varied from those before the pandemic. In a study with parents of preschool children in the US, Stites et al. (2021) found that about 60% of parents reported spending less than one hour on distance learning, with 16% of parents reporting they did not spend any time on distance learning. A large-scale survey with early childhood education (ECE) teachers found that preschoolers struggled with remote learning due to inadequate instructional provisions, parents’ difficulties in supervising online preschool while working, the need for physical activity, difficulty sitting in front of computers, and challenges in learning social and school readiness skills without in-person interaction (Bassok et al., 2021). In the current study, the loss of regular preschool stimulation also included periods of atypical preschool stimulation. Thus, the COVID-19 effects described above cannot be limited to how parents interact (or lack thereof) with their children. In other words, why preschools were unable to close that gap between pre- and post-COVID cohorts? It is feasible that preschool routines during the transition period or “new normal” (about 7 months between the remote learning and the return to regular in-person preschool stimulation) were severely affected by health and safety measures. These measures constrained classroom interactions that could affect the child’s cognitive development. For instance, activities such as singing songs were limited. These activities contribute to the development of phonological processing skills and constitute pedagogical approaches to support, for instance, the understanding of the count sequence in young children (Degé & Schwarzer, 2011). Masking could also affect the development of phonological processing given the role of articulatory awareness when learning new sounds or in training phonological processing (Wise et al., 1999). It is worth mentioning that the impact on phonological awareness is notable because studies suggest that parents of young children focused on literacy-related activities during the COVID-19 pandemic (Stites et al., 2021). Some studies have found that parents increased their engagement in home literacy activities. For example, Wheeler and Hill (2021) found that parental reading practices with two- to four-year-old children did change during COVID-19—parents reported reading more often during COVID-19 compared to before COVID-19. This could have had an impact on children’s phonological awareness. Indeed, studies that have assessed young children’s language and pre-literacy skills during the COVID-19 pandemic have shown no gaps between pre- and post-COVID cohorts. For instance, Kartushina et al. (2022), with a large cross-country sample that included Spanish-speaking children, assessed (indirect assessment) toddler-age children’s vocabulary gains during the major COVID-19 lockdown (2020 March–September) and found that children gained more words than expected compared to pre-pandemic norms. Lynch et al. (2023) investigated a different pre-literacy skill—print knowledge—using remote assessment and found no (short-term) effects of loss of stimulation during the COVID-19 pandemic. One potential explanation of why our findings do not align with these studies is that we used direct assessment and did not rely on parental reports or remote assessment, which could be very challenging for young children. Furthermore, we focused on phonological awareness which shares some variance with other pre-literacy skills such as print knowledge and oral language, but it is a different skill. Because phonological awareness improves substantially with reading practices (Perfetti et al., 1987), it is possible that either parental reports on their engagement with young children during the COVID-19 pandemic overstate their role and activities or that the effect of such activities is limited. As mentioned above, the COVID-19 pandemic created circumstances that challenged how parents interacted with their children (Bassok et al., 2021). Our study also revealed that the loss of regular in-person preschool stimulation affected both academic and non-academic domains. Children in post-COVID cohorts showed poorer non-verbal reasoning skills and working memory capacity than children who experienced regular preschool stimulation (before the pandemic). Although these skills are not typically targeted by preschool curricula, it is possible that what teachers do in the classroom impacts the development of young children’s non-verbal reasoning skills and working memory capacity. For instance, the quality of preschool experiences and nature of interactions between teacher and children contribute to the development of non-academic skills (Hamre et al., 2014). Similarly, activities that support the development of academic skills in preschoolers, for instance, recalling the verbal count sequence, may incidentally contribute to the development of working memory capacity. Younger Children are More Affected by the Loss of Regular In-person Preschool Stimulation Another finding of the current study is that the impact of the loss of in-person preschool stimulation during the COVID-19 pandemic was particularly relevant at earlier stages of development. Children who experienced such loss during the first year of preschool (when children turn 3 years old) showed deficits across a wide range of academic and non-academic domains one year later—compared with children who had attended regular in-person preschool stimulation before the pandemic. In contrast, disparities between pre- and post-COVID cohorts were circumscribed to non-academic aspects (working memory and visuospatial working memory) in older children who experienced the loss of preschool stimulation during their second year of preschool. Thus, the possibility that parents and remote learning opportunities did not contribute to children’s cognitive development seems more plausible for younger children (3-year-olds who experienced loss of regular preschool stimulation during their first year of preschool). Note that the effect size corresponding to single-digit arithmetic was very small. As suggested by Tomasik et al. (2020), younger children’s reliance on continuous cognitive scaffolding may explain why these children were more affected by the loss of regular preschool stimulation than older children in the current study. Such reliance on cognitive scaffolding could be more substantially affected by the special circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is also noteworthy that older children in post-COVID cohorts exhibited better visuospatial skills than children in pre-COVID cohorts. This finding, while unexpected, could reflect a higher degree of engagement with digital materials during remote learning periods. Although we do not have information regarding the specific types of materials that older children in the current study were presented with, there is some evidence that engaging with certain types of digital materials may be associated with the development of visuospatial skills. For instance, some studies have found positive associations between playing video games that require spatial reasoning and visual attention, and enhanced performance on tasks measuring visuospatial skills (e.g., Green & Bavelier, 2003; Spence & Feng, 2010). It is plausible that the increased use of digital platforms for learning and entertainment during the pandemic, even if not specifically designed to target visuospatial skills, may have inadvertently provided older children in the post-COVID cohort with more opportunities to practice and develop these abilities. However, further research is needed to investigate this possibility and understand the specific ways in which different types of digital engagement might influence visuospatial development in young children. Finally, it is worth mentioning that our findings moderate those of another study that focused on preschool children (Lynch et al., 2023). Overall, Lynch et al. (2023) found very limited evidence of the loss of regular preschool stimulation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because our study involved long-term effects (more than one year of atypical preschool stimulation), a sample from a different SES stratum, direct assessments, and we disentangled the role of children’s age, it is difficult to establish a straightforward comparison. However, if we only consider older children in the current study—those who experienced the loss of regular preschool stimulation when they were 4 years old—, then, our findings align with the limited effect reported by Lynch et al. Altogether, our findings and those from previous studies that have investigated the effect of COVID-19 on children’s learning, suggest that there is not a linear association between learning losses and the child’s age. In this sense, differences in cognitive capabilities, parental involvement, as well as difficulty of academic content likely explain why some children showed learning losses and others did not. For instance, Lynch et al. (2023) argued that differences with studies that have focused on school-age children could relate to the possibility that parents found it easier to ‘home teach’ preschool concepts, such as oral counting, as compared with the more advanced mathematics and other academic content that school-age children were expected to learn. Therefore, parents could have been better equipped to mitigate the effects of school closures on preschoolers’ than older students’ learning outcomes (p. 262). Limitations and Further Research In the current study, we have provided novel evidence of how the loss of regular in-person preschool stimulation during the COVID-19 pandemic affected the development of young children. However, our research has some limitations. First, data regarding how parents engaged with their children in pre- and post-COVID cohorts were not available for the current study and are very limited in existing studies on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, our arguments regarding the role of parents and the home environment to explain the findings of the current study need further support, especially considering the growing evidence that parental practices in the home contribute to children’s cognitive development (e.g., Muñez et al., 2021). Second, when children returned to school after the closures—i.e., during the “new normal”—there could have been differences across participating classrooms and schools regarding health and safety measures such as adjusting usual routines and activities, reducing group sizes, physical distancing, and masking guidelines. These aspects could affect the variability within post-COVID cohorts and the quality of in-person preschool stimulation that these children received. Although our study focused on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young children’s development, addressing the scarcity of research regarding the pandemic’s effect on this population, the findings suggest potential avenues for future research on how regular in-person preschool stimulation (or lack thereof) differentially contributes to developing cognitive skills in young children. For instance, our findings warrant additional research to assess more clearly the joint long-term contribution of parents and in-person preschool stimulation to developing these skills in early childhood. Our study also highlights that the effect of the loss of regular in-person preschool stimulation varies substantially as a function of the child’s developmental stage, warranting additional research efforts to investigate comprehensively how young children interact with technology (online learning resources). This research may have broader implications, such as how to best support the learning of children who do not have access to regular in-person preschool stimulation. Despite the research efforts on the benefits of early childhood education—in the context of WEIRD socio-demographic contexts—there are still many children who face no learning opportunities at all in other than WEIRD contexts. In this sense, family education programs serve as a valuable resource to address the lack of stimulation during the preschool stage by providing families with structured guidance on appropriate educational practices within the home environment. Through these training processes, parents gain a deeper understanding of early childhood development and strengthen key parenting skills in different areas. This collaboration between family and school promotes the creation of enriched learning environments, helping to reduce developmental gaps, particularly in vulnerable contexts or those with limited access to formal educational resources. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. 1 The path model with a censored-normal regression fitted the data worse (larger BIC value) than the model in which that regression was specified as censored-inflated. This means that including a separate equation for class membership improves the fit of the model to the data. Funding This paper was supported by grant PGC2018-100758-B-I00 from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding body and the authors’ institutions. Cite this article as: Muñez, D., Orrantia, J., Sanchez, R., & Muñoz, P. (2026). Long-term effects of the loss of stimulation during the COVID-19 pandemic on preschoolers’ cognitive development. Psicología Educativa, 32, Article e260444. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a1 References Appendix Supplementary Material The TEDI-MATH test comprises six subtests (knowledge of number word sequence, enumeration, understanding the number system, logical operations, arithmetical operations, and size estimation), including a total of 26 different tasks. As illustrated in Table S1, only 14 tasks from three subtests (knowledge of number word sequence, enumeration, and arithmetical operations) were used in the current study. For each task, children were presented with one or more questions. The correct response to each question was awarded one point, with the exception of Task 1 (two points were awarded if the child was able to count without errors and without assistance). The tasks were administered in a fixed and systematic order as outlined in Table S1, with only two exceptions. If a child failed the two questions of Task 6, they were immediately directed to Task 8. Conversely, Task 14 was terminated after five consecutive errors. Table S1 specifies the maximum score that can be achieved for each task and subtest. It is important to note that Task 13 was shortened due to the age of the children in our study, with only 16 questions (out of 54) being presented. The raw score for each subtest was used in analyses. |

Cite this article as: Muñez, D., Orrantia, J., Sanchez, R., & Muñoz, P. (2026). Long-term Effects of the Loss of Stimulation during the COVID-19 Pandemic on Preschoolers’ Cognitive Development. PsicologĂa Educativa, 32, Article e260444. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a1

Correspondence: orrantia@usal.es (J. Orrantia).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

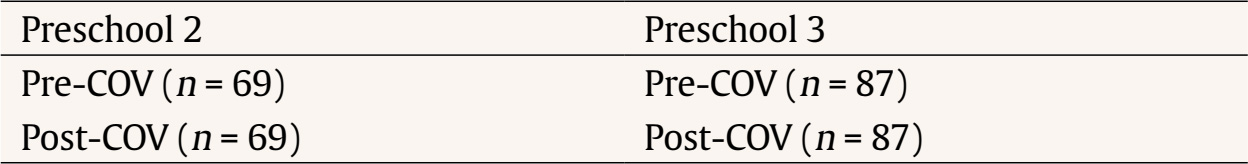

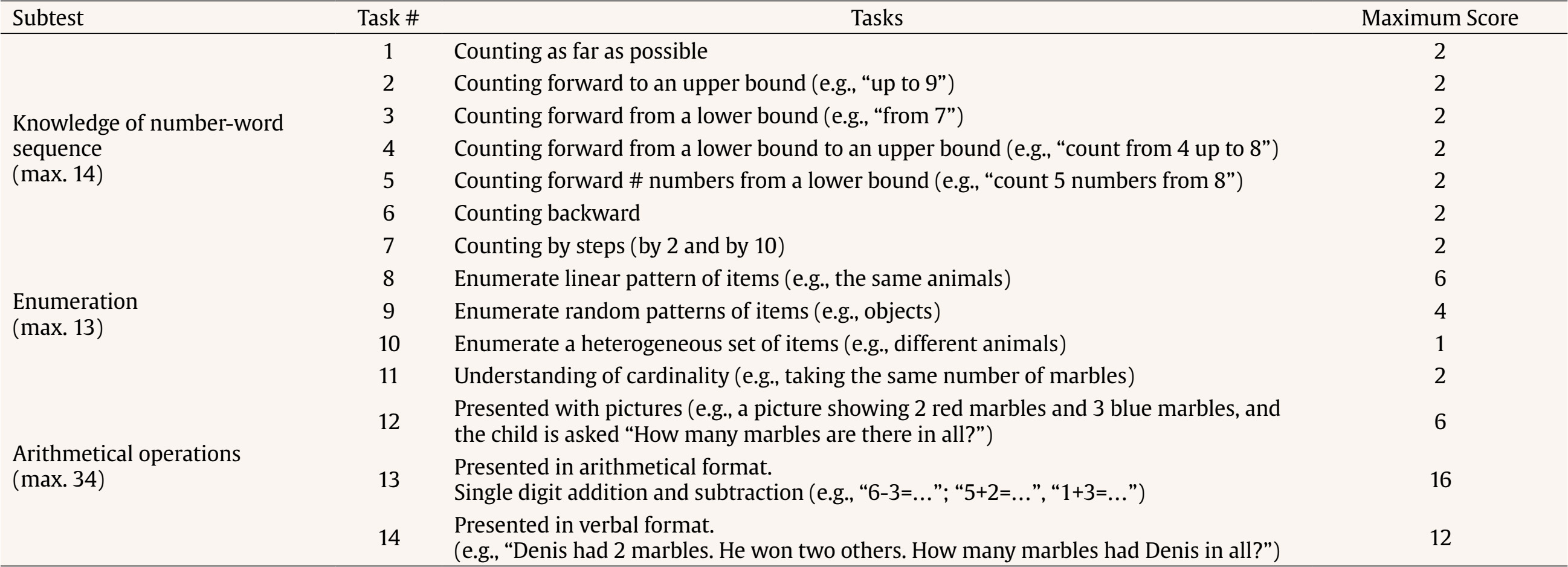

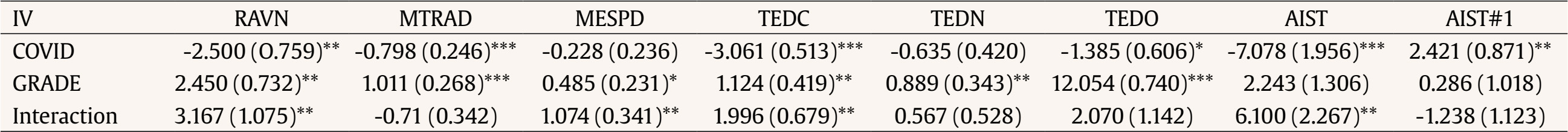

JATS