Educational Escape Room for Psychology Students: Exploring Design Structure and Effectiveness

[La sala de escape educativa para estudiantes de psicologĂa: análisis del diseño de su estructura y eficacia]

Carlos Valls-Serrano1, Harry Moore1, María J. Rabadán-Pardo1, Paloma Egea-Cariñanos2, & María Vélez-Coto1

1Universidad CatĂłlica de Murcia, Spain; 2Universidad de Granada, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a2

Received 10 October 2024, Accepted 29 May 2025

Abstract

Educational escape rooms (EERs) have shown to be a motivating and enjoyable teaching activity, yet few studies have examined their impact on learning when compared to traditional teaching techniques. This study investigates the impact of EERs on students’ academic experiences, focusing on their effectiveness in promoting learning outcomes compared to traditional teaching methods. A total of 83 psychology students participated. This study employed both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Quantitative results revealed that participants evaluated EERs positively, with the experimental group achieving superior learning outcomes. No differences in learning based on EER structures were identified in the analysis. Qualitative analysis supported the quantitative findings but also identified challenges, such as task distribution, difficulty managing group work, and handling pressure or frustration. Teachers raised concerns regarding the activity’s complexity and its limited impact on learning outcomes. Despite these challenges, EERs were perceived as motivating and beneficial for learning specific contents.

Resumen

Las salas de escape educativas (SEE) constituyen una actividad didáctica motivadora y gratificante, si bien hay pocos estudios que analicen su influencia en el aprendizaje en comparación con las técnicas de enseñanza tradicionales. Este estudio analiza la repercusión de las SEE en las experiencias académicas de los estudiantes, centrándose en su eficacia en los resultados del aprendizaje en comparación con los métodos de enseñanza tradicionales. En el estudio participaron 83 estudiantes de psicología, empleándose tanto metodologías cuantitativas como cualitativas. Los resultados cuantitativos muestran que los participantes tienen una opinión positiva de las SEE, siendo mejores los resultados del aprendizaje del grupo experimental y no se apreciaron diferencias en el aprendizaje según las estructuras de las SEE. El análisis cualitativo confirmó los resultados cuantitativos, aunque también surgieron dificultades, como la distribución de tareas, complicaciones en la gestión del trabajo en grupo y del tratamiento de la presión o la frustración. Los profesores expresaron preocupación por la complejidad de la actividad y su efecto limitado en los resultados del aprendizaje. A pesar de estas dificultades, se consideró que las SEE eran motivadoras y beneficiosas para el aprendizaje de contenidos específicos.

Palabras clave

Educativo, Sala de juegos, PsicologĂa, Aprendizaje, Desempeño acadĂ©micoKeywords

Educational, Escape room, Psychology, Learning, Academic performanceCite this article as: Valls-Serrano, C., Moore, H., Rabadán-Pardo, M. J., Egea-Cariñanos, P., & Vélez-Coto, M. (2026). Educational Escape Room for Psychology Students: Exploring Design Structure and Effectiveness. PsicologĂa Educativa, 32, Article e260445. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a2

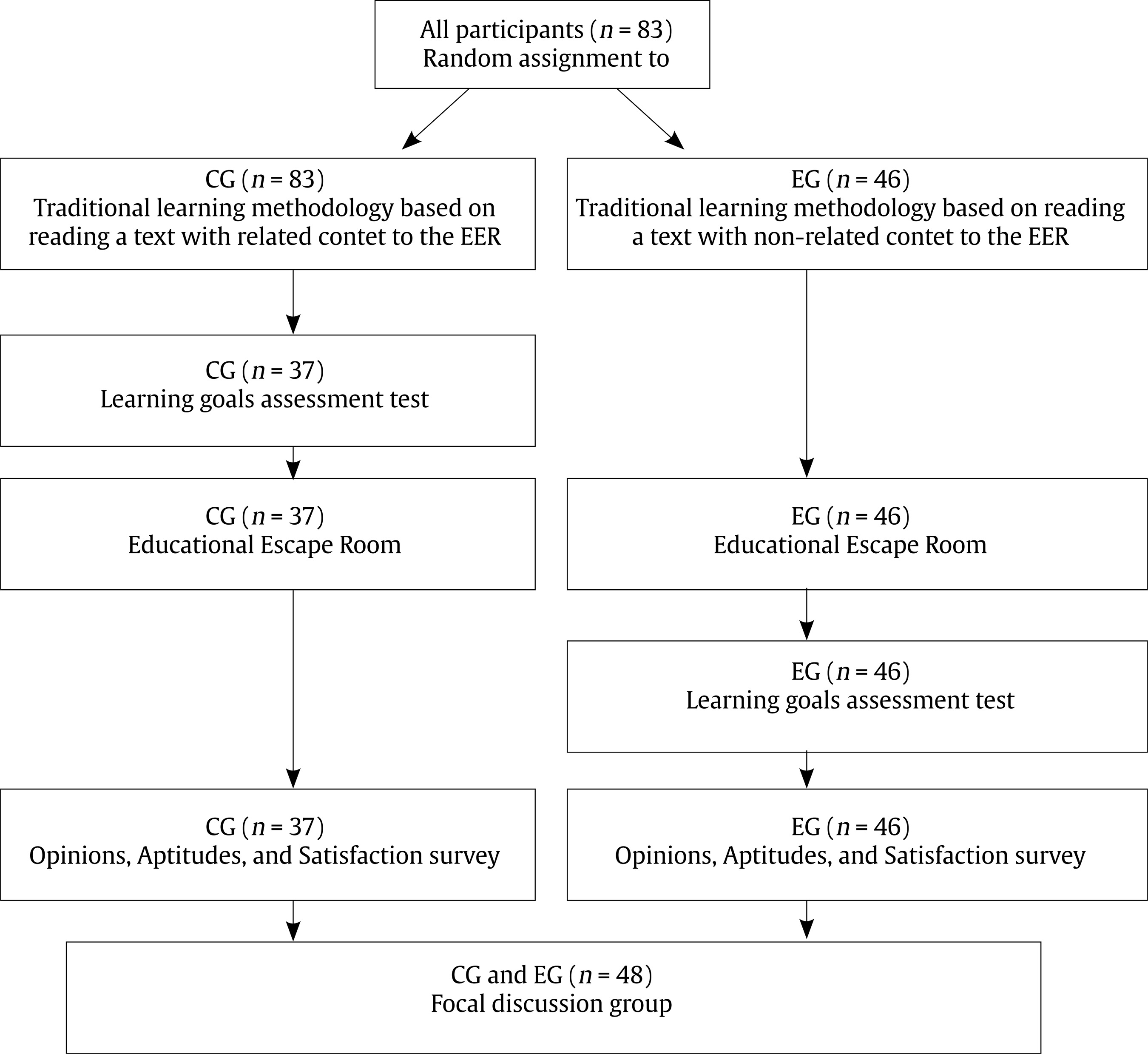

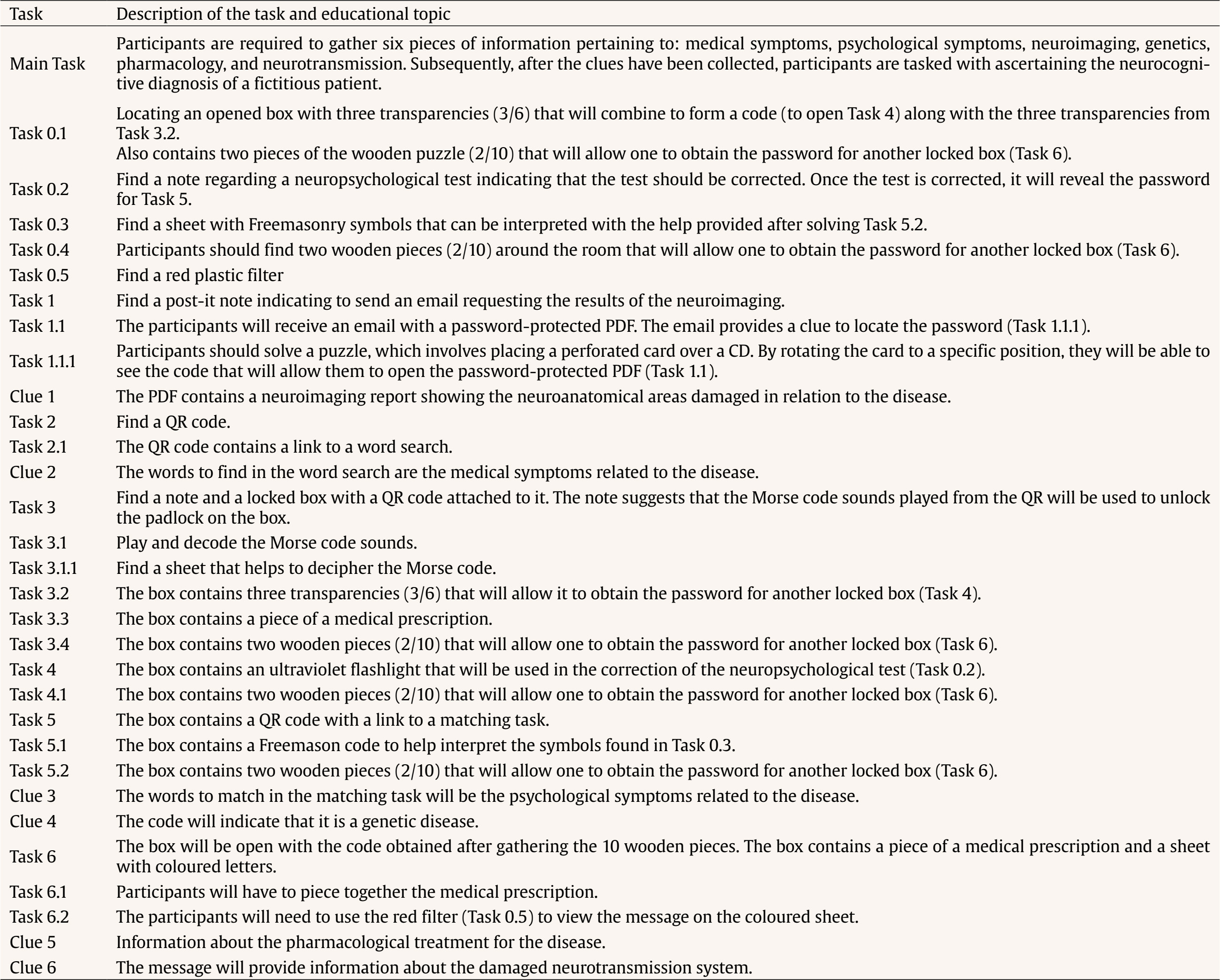

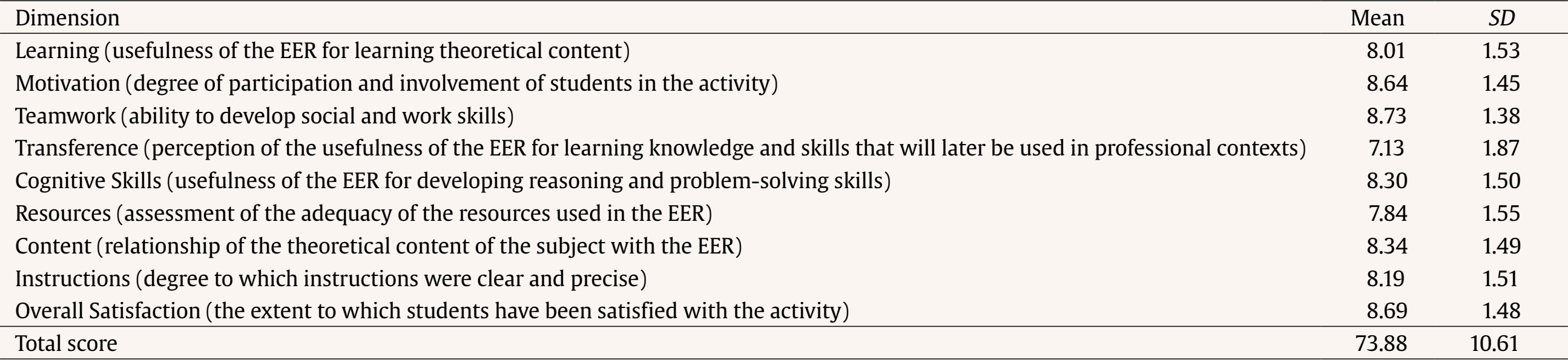

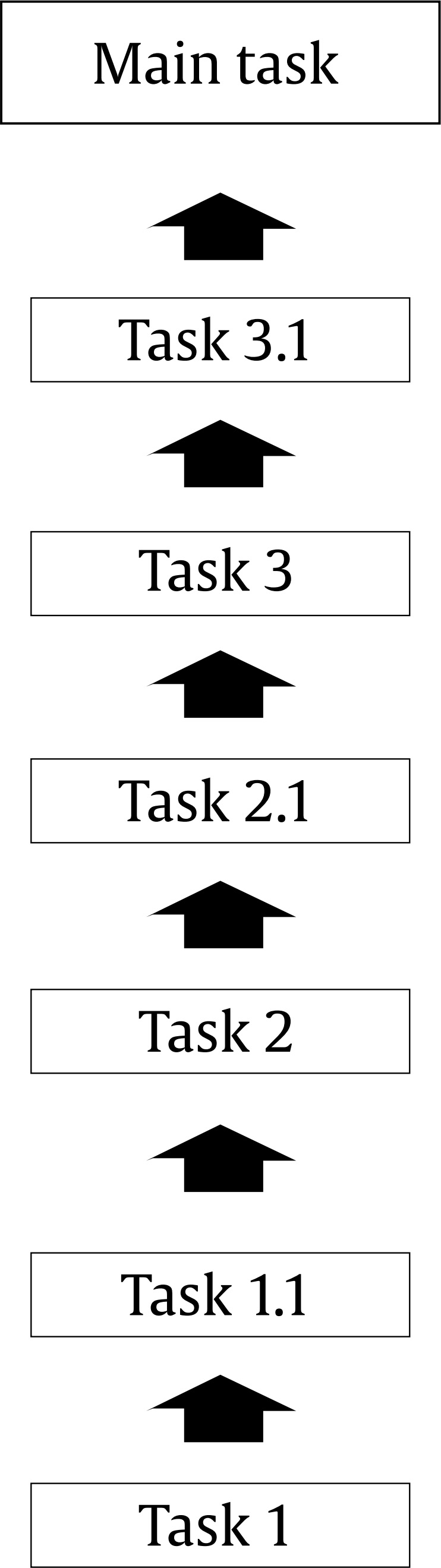

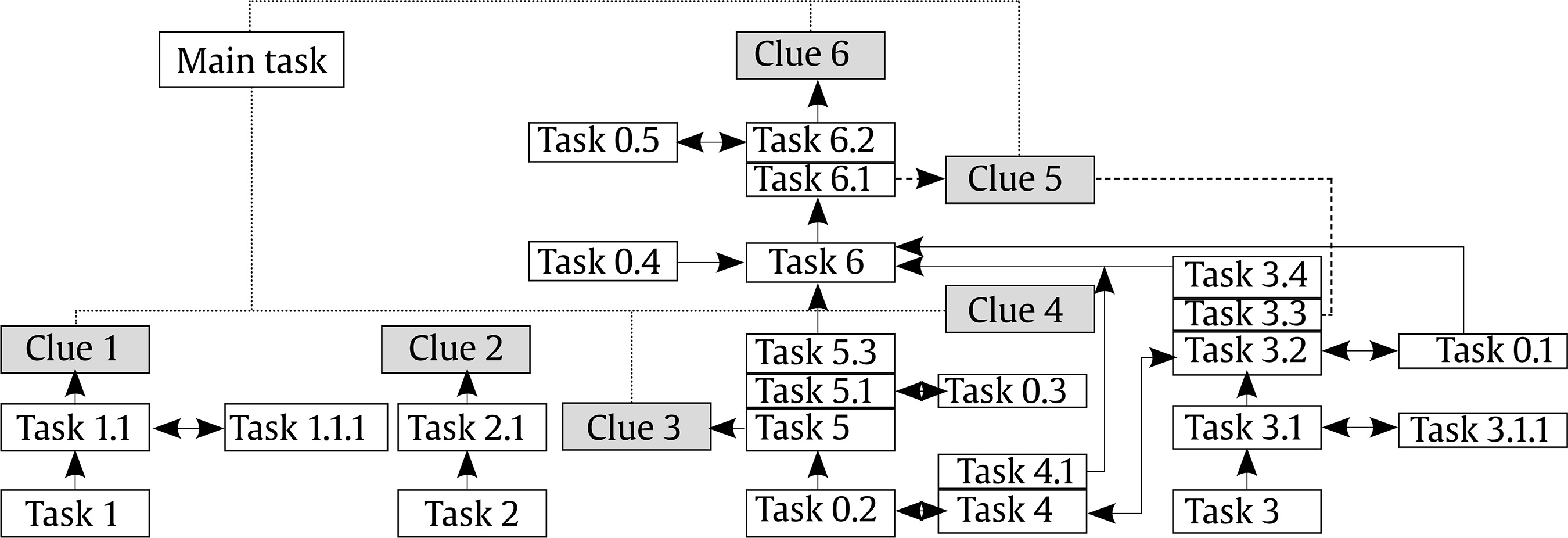

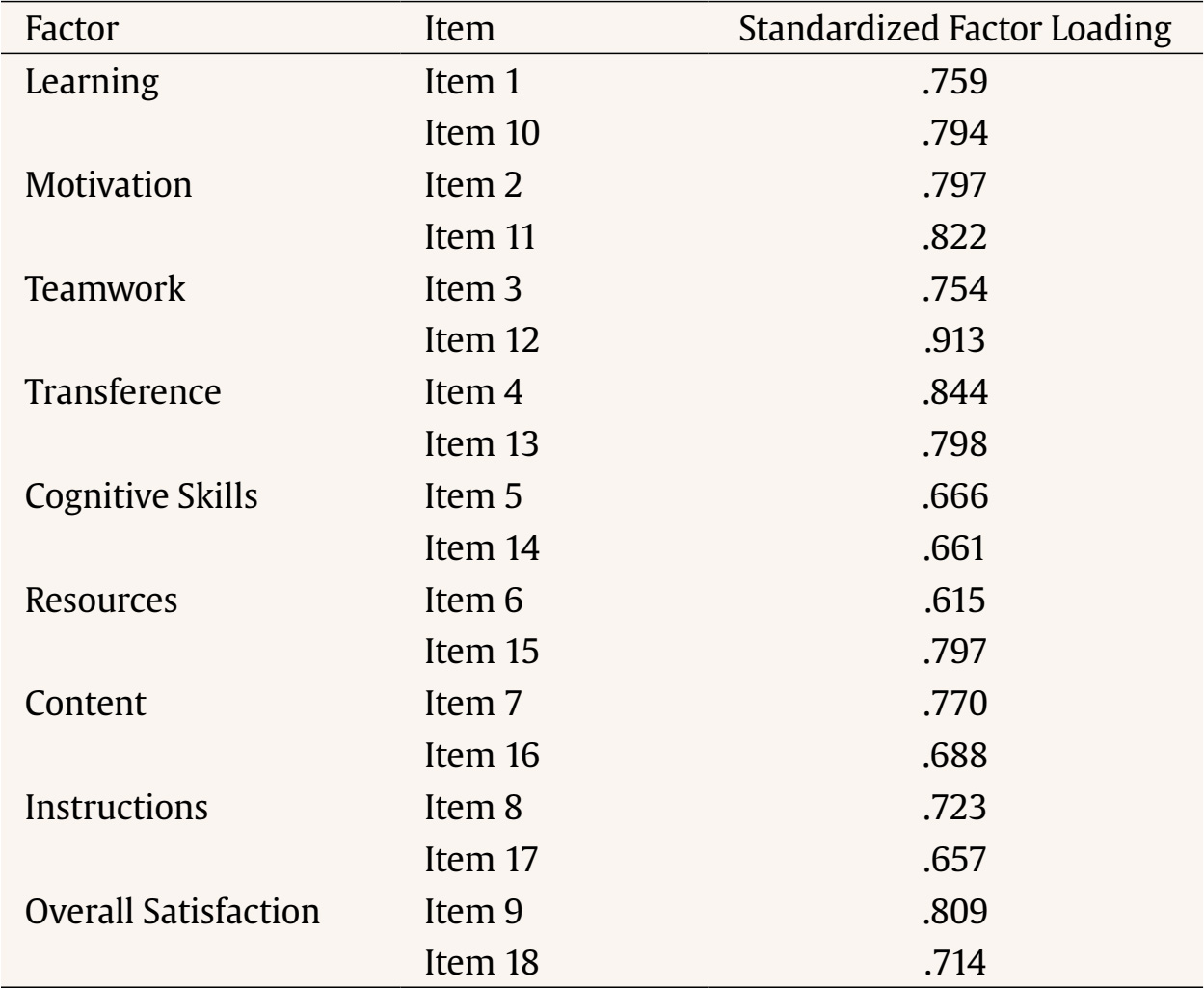

Correspondence: htamoore@ucam.edu (H. T. A. Moore).Escape rooms are immersive, collaborative games where a group of participants tackle a series of challenges within a set timeframe, with the goal of accomplishing a mission, typically inside a room (Nicholson, 2015). Since their inception in 2007, escape rooms become a highly popular leisure activity worldwide. The increasing interest in these activities can be explained by their challenging nature, the opportunity they offer to engage in movie-inspired or historical scenarios, and the distinctive collaborative aspect that distinguishes them from traditional competitive games (Van Gaalen et al., 2021). Unsurprisingly, escape rooms soon began to be used in educational contexts for instructional purposes, evolving the concept to what is now termed educational escape rooms (EER) (Clarke et al., 2017). EERs are defined similarly to traditional escape rooms, although they are explicitly designed for domain knowledge acquisition or skill development (Fotaris & Mastoras, 2019). They are often adapted to educational contexts, using both analog (e.g., boxes, locks, etc.) and digital materials (e.g., QR codes, videos, etc.), while simplifying thematic influences and playful elements to emphasize learning objectives. EERs are a versatile tool suitable for diverse audiences, with previous research suggesting their effectiveness across a range of educational stages, from elementary school (Vidergor, 2021) to higher education (Guckian et al., 2020). Although EERs have been applied in different fields like natural sciences, arts, and humanities (Fotaris & Mastoras, 2019; Ross & Bennett, 2020), the greatest interest has been noted in health sciences (Guckian et al., 2020; Molina-Torres et al., 2022), including, though to a lesser extent, in psychology (LaPaglia, 2020; León & Tadeu, 2022). The main findings of these studies consistently reflect positive outcomes, highlighting primarily the increase in motivation, fostering a favorable attitude towards learning, and being perceived as both enjoyable and entertaining (Taraldsen et al., 2022). Moreover, EERs also appear to promote the development of teamwork and communication skills (Sarage et al., 2022; Valdes et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2018). However, while there is a general trend of positive outcomes, it is important to acknowledge that some studies have reported negative or neutral effects on learning performance with the use of EERs, even though such instances are relatively scarce. Despite these null or negative findings, participants in these studies ultimately reported a positive overall experience (Clauson et al., 2019; Duncan, 2020; Huang et al., 2020). EER use is not a new approach in education, as numerous studies have already been published on the topic (Fotaris & Mastoras, 2019; Veldkamp et al., 2020). However, while many of these studies highlight participants’ experiences and motivation, only a few provide an in-depth analysis of the actual knowledge and skill acquisition outcomes achieved (Aubeux et al., 2020; Clauson et al., 2019; Cotner et al., 2018; Dimeo et al., 2022; Eukel et al., 2017; Gordillo et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020). Furthermore, they fail to comparatively analyze the benefits in relation to other traditional learning techniques (techniques in which the student receives information in a one-way direction, without active engagement or collaborative activities) and many of them do not incorporate control groups (Buchner et al., 2022). The state of the literature calls for advancing EER research that allows the exploration into their impact on learning beyond the motivational or experiential competencies and calls for the development of more precise methodological designs. In the same vein, and concerning the design of EERs, few studies have addressed how their structure may influence motivational and learning outcomes. EERs are a flexible tool that can be designed in multiple and creative ways. In this regard, Nicholson (2015) describes four types of design based on the organization of their puzzles: open (problems can be solved without a specific order), sequential (problems must be solved one after another), path-based (there are different paths that can be started without a specific order but each path contains an ordered sequence of tasks), and finally the pyramidal structure, which would be the most complex of all and includes the three previous structures. In the field of health sciences, most EERs developed to date have adopted a sequential design (Veldkamp et al., 2020). The design and structure of a problem are critical factors influencing both the problem-solving approach and the cognitive skills required for its resolution (Reed, 2016). From a cognitive psychology standpoint, problems are traditionally classified along a continuum from well-structured to ill-structured. Well-structured problems have clearly defined objectives and offer direct solutions, with all necessary information readily accessible, whereas ill-structured problems involve multiple possible solution pathways and are characterized by uncertainty due to ambiguous or incomplete information (Auni & Kohar, 2023). In this context, it can be argued that EER designs with sequential structures may align more closely with well-structured problems, while pyramid structures may better reflect the complexities of ill-structured problems. Thus, it may be that case that the structure of an EER could significantly increase the cognitive demands placed on participants and, consequently, the learning outcomes. From an educational perspective, pedagogical strategies that focus on developing skills for addressing ill-structured problems have been highly valued in various domains (Pulgar et al., 2020). One of the key objectives of teacher education is to prepare students to become proficient problem solvers, particularly with ill-structured problems, which closely mirror real-world challenges. As a result, the ability to navigate and resolve ill-structured problems has been related to better learning outcomes and equips students with the necessary skills to adapt to the dynamic and unpredictable nature of future work environments (Iwuanyanwu, 2020). Therefore, it may be the case that participating in pyramidal EERs may be associated with greater learning outcomes, compared to other EER structures that suppose a more well-defined problem, such as sequential EERs. In summary, EER studies have demonstrated to be a useful educational tool in academic contexts. However, there is a need for further advancement in research methodologies within this field, incorporating more intricate approaches that facilitate a comparative analysis of traditional teaching techniques, examining the impact on knowledge acquisition (theoretical and conceptual information), including control groups in the design, or exploring structural characteristics, among other aspects. Therefore, the objectives of this study were threefold: (1) to analyze the experience of the use of EER in psychology degree students as well as from the perspective of the teachers; (2) to explore how EERs and other traditional teaching techniques (techniques in which the student receives information passively, without direct involvement or collaborative activities) may impact differently on knowledge acquisition (theoretical and conceptual information); and (3) to analyze the differences between various structure designs of EERs and how they relate to student experience and learning. Our hypotheses are that students will perceive EERs as a positive, motivating, and satisfying academic tool. Students who underwent an EER will show greater knowledge acquisition than those evaluated after other traditional teaching techniques. Finally, students who participate in the pyramidal EER (P-EER) will show greater satisfaction and learning compared to those who participate in a sequential EER (S-EER). Design and Participants A total of 83 psychology students participated in the study, of whom 17 were male (20.5%) and 66 were female (79.5%). The mean age of the sample was 21.22 years (SD = 4.65). Participants were recruited at the Universidad Católica San Antonio, Murcia, Spain, within neuroscience-related courses between September 2023 and May 2024. The final sample was composed of students belonging to the following courses: Fundamentals of Psychobiology , Physiological Psychology , Neuropsychology , and Neuropsychological Assessment. To analyze the first objective, this study employed both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies, with a descriptive nature, focusing on the experiences related to the EER and its impact on knowledge acquisition. To assess the second objective—comparing knowledge acquisition between the traditional learning approach and EER—an experimental group (EG, n = 46) and a control group (CG, n = 37) were set. Group assignment was randomized. Due to the fact that CG participants completed the traditional learning technique and the assessment test on a different day than the EER, there was a sample loss. For the third goal, which compares knowledge acquisition between the two types of EER structure, only participants from the experimental group were considered, with a sample size of GE-P-EER (n = 30) and GE-S-EER (n = 16). The sequential and pyramidal structures were chosen for comparison due to their marked structural differences, which offer the most suitable conditions to test the proposed hypothesis. Additionally, the sequential structure more closely resembles well-structured problems, while the pyramidal structure aligns more with ill-structured problems. On one hand, Veldkamp et al. (2020) consider S-EERs to be relatively easier to apply to large groups and in open spaces without the need to use several classrooms and physical resources compared to the P-EER, since it mainly requires basic resources such as boxes with locks and QR codes. On the other hand, P-EERs have a structure similar to traditional escape rooms and therefore require specific rooms and a variety of physical resources to implement the tasks. For that reason, an S-EER was employed in the classrooms with a large number of students, and P-EERs were carried out in the classrooms with smaller numbers of students. A description of the tasks can be seen in Table 2. In order to compare knowledge acquisition between the two types of EER structure, only participants from the experimental group were considered, with a sample size of GE-P-EER (n = 30) and GE-S-EER (n = 16). Instruments Sociodemographic Variables Basic demographic information about the participants was collected, such as age, gender, academic year, prior experience with both leisure, or educational escape rooms. Opinions, Attitudes, and Satisfaction with the EER Survey An ad hoc survey was designed to assess students’ opinions, attitudes, and overall satisfaction with the EER. The survey consists of 18 questions on a Likert scale with 5 response options (1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = to some extent, 4 = a lot, 5 = very much). One of the participating teachers was responsible for developing an initial version of the ad hoc survey for the study. The procedure included the following steps: defining the assessment goal, reviewing the literature in the field, elaborating the questions, categorizing the items into different dimensions, and selecting the question type. The four teachers participating in the project reviewed the scale and appropriate revisions were made. Finally, two student interns from the department reviewed the scale to assess any potential comprehension issues, but no issues were detected. The questions were designed to assess the following dimensions: Learning (usefulness of the EER for learning theoretical content), Motivation (degree of participation and involvement of students in the activity), Teamwork (ability to develop social and work skills), Transference (perception of the usefulness of the EER for knowledge acquisition and skills that will later be used in professional contexts), Cognitive Skills (usefulness of the EER for developing reasoning and problem-solving skills), Resources (assessment of the adequacy of the resources used in the EER), Content (relationship of the theoretical content of the subject with the EER), Instructions (degree to which instructions were clear and precise), and Overall Satisfaction (the extent to which students were satisfied with the activity). A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to validate these dimensions. The results can be found in the results section. The survey can be found in Appendix, Table A1 and Table A2. Knowledge Acquisition Test (KAT) In each course, a learning goal was chosen, which served as the central content for both the traditional theoretical activity and the EER. In Fundamentals of Psychobiology the content that was chosen was aphasia; in Physiological Psychology the content was sleep disorders; Neuropsychology included Lewy bodies dementia; and Neuropsychological Assessment included neurocognitive disorders. Consequently, the member of the research team responsible for each course created a multiple-choice assessment test with three choices, of which only one was correct. All the tests were supervised collaboratively and designed by the remaining teachers to ensure consistency in the structure of the test. The maximum possible score of tests ranged between 0 and 10 points. The test was crafted in accordance with Tyler’s (2013) Goal-oriented approach by adhering to the subsequent stages: identification of learning objectives, content selection, determination of knowledge levels, question design, test construction, piloting, and review and adjustments. All the tests were supervised collaboratively designed by the remaining teachers to ensure consistency in the structure of the test. The maximum possible score of the tests ranged between 0 and 10 points. Open Questions Interview Within a maximum period of seven days after the conclusion of the EERs, a group of students were interviewed to gather their opinions about the activity, with the intention of capturing their narratives, assessments, and points for improvement. Their responses were collected without distinguishing whether they participated in a P-EER or an S-EER. Seven group interviews were conducted, in English and Spanish according to participants’ native language. The number of participants varied between 4 and 12 in each interview. Upon completion, the participants were completely anonymized and the audio recordings were transcribed and analyzed using the qualitative research technique of content analysis. Additionally, upon completion of the project, individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with the four teachers who led the activity. The goal was to investigate a topic not extensively covered by previous literature: the motivation received by teachers in their educational role when incorporating play-based educational strategies in their teaching practices. Teachers were also queried about their assessment of the activity, the difficulties they observed, and their behaviors’ self-evaluation. The interviews were recorded in audio, anonymized, transcribed, and analyzed. Procedure The study was approved by the ethics committee of the university (Ref. CE072206). All participants were informed about the educational innovation project, the objectives of the study, the confidentiality of the data collected, and that their participation was voluntary. The students gave the researchers their consent to use their data and a digital document was signed specifying that the data would be used for scientific purposes. No student declined the invitation to participate in the study. An overview of the full procedure is provided in Figure 1. First, the students had been informed and their consent was obtained, a day within the academic schedule for each subject was designated for the traditional teaching activity, which took place in a regular classroom. All participants completed a traditional teaching activity, consisting of a self-study task (15-30 minutes) focused on theoretical content, such as reading a book chapter or manuscript. Those randomly assigned to the CG were assigned readings related to the topic addressed in the EER, whereas those in the experimental group completed a task with theoretical content on a different topic. After this activity, students undertook the KAT to obtain a quantitative score of the knowledge about the topic. This test was administered within seven days following the activity, maintaining an equivalent time interval for both groups. Figure 1 Flow Diagram of Study Design and Participants.   Note. CG = control group, EG = experimental group. The EER was conducted on a different day within the academic schedule (20-40 minutes), in which both groups participated in groups of 4 to 6 students. The S-EER was carried out in a classroom and outside in the university campus. The S-EER description can be found in Figure 2 and Table 1, which details the flowchart, and outlines the tasks, respectively. Table 1 List of Tasks Outlined for the S-EER on a Clinical Case of Aphasia in the Fundamentals of Psychobiology Course   Note. S-EER = sequential educational escape room; QR = quick response. With regards to P-EERs, these were conducted in two rooms belonging to the psychology laboratory. The rooms were equipped with a variety of puzzles and resources for students to use in order to complete each task and advance to the next one. In all EERs, a narrative related to the final goal was created to enhance immersion (e.g., students had been trapped and would only be released upon finding a patient’s diagnosis). Participants were informed to solve the entire puzzle as quickly as possible. All groups had a maximum resolution time of 1 hour. Two teachers monitored the activity and addressed any questions or potential issues during the activity. The flowchart outlining the structure of the P-EER is presented in Figure 3, and a description of each task is provided in Table 2. Table 2 List of Tasks Outlined for the P-EER on a Clinical Case of Huntington’s Disease in the Neuropsychological Assessment Course   Note. P-EER = pyramidal educational escape room; PDF = portable document format; CD = compact disc; QR = quick response. After the EERs, the EG completed the KAT that the CG had completed in the previous session. Both the CG and EG completed the Opinions, Attitudes, and Satisfaction with the EER survey. Finally, some students, both from the CG and EG were selected randomly for a focus group discussion for the open question interviews of their experiences. An overview of the full procedure is provided in Figure 1. Statistical Analysis To assess the structural validity of the Opinions, Attitudes, and Satisfaction with the EER survey, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using the lavaan package in R (Rosseel, 2012). The DWLS (diagonal weighted least squares) estimator was used, given that the data come from an ordinal Likert-type scale. This estimator is recommended for ordered categorical variables, as it corrects for possible biases in parameter estimation and improves the precision of fit indices in small or moderate samples (DiStefano & Morgan, 2014). Additionally, since latent factors do not have an inherent measurement scale, their variance was set to 1 to scale them (Brown, 2015). The proposed model consisted of 9 latent factors, each represented by two items, and covariation between latent factors was allowed. Model fit was assessed using the robust comparative fit index (CFI) and the robust Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), given that the DWLS estimator was used. Values greater than or equal to .95 suggest excellent fit. The robust root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was also evaluated, with values below .05 indicating a close fit to the data. The robust standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) was used as an additional indicator with values below .08 considered indicative of good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Furthermore, factor loadings were evaluated following the recommendations of Hair et al. (2014) where values ≥ .70 suggest a strong association between the item and its latent factor, values ranging between .40-.69 are acceptable, and values < .40 indicate a weak association. Exploratory analyses were conducted to detect outliers or missing values. No outliers were detected, and 7 missing values were found regarding the Learning Goals Assessment Test. Descriptive analyses were carried out to determine the sociodemographic characteristics of participants. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to analyze the normal distribution of the variables, and the results recommended the use of non-parametric tests for independent groups comparison, and consequently the Mann-Whitney’s U test was performed. To analyze differences in KAT outcomes between EERs and traditional teaching activities, a Mann-Whitney’s U test compared scores on the knowledge tests between students in the experimental group and students in the control group. To analyse differences in KAT between S-EER and P-EER, a Mann-Whitney’s U test compared scores on the knowledge tests between students in the experimental group that completed the S-EER and students in the experimental group that completed the P-EER. The exploratory and comparison analysis were performed using the SPSS statistics program. Confirmatory Factor Analysis The model presented an excellent fit to the data, with values within the recommended ranges for confirmatory factor models: CFI = .975, TLI = .961, RMSEA = .035 (90% CI [.000, .070), SRMR = .059. These results indicate that the proposed factor structure adequately represents the observed variance-covariance in the data (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Schreiber et al., 2006). The standardized factor loadings ranged from .657 to .913 (Table 3), indicating an adequate relationship between the items and their respective factors. No factor loadings below .40 were observed, and therefore, no item was eliminated. Furthermore, all covariances between factors were significant (p < .001), suggesting a significant interrelationship between the constructs assessed. Overall, the results obtained confirm the factorial validity of the model, supporting the proposed theoretical structure. Quantitative Results In Table 4, descriptive results regarding opinions, attitudes, and satisfaction with the EER are displayed. The results show a high level of agreement in all dimensions, with the Teamwork dimension standing out with the highest score, and the Transference dimension obtaining the lowest score of all. Table 4 Mean and Standard Deviation of the Opinions, Attitudes, and Satisfaction with the EER Questionnaire   Note. SD = standard deviation; EER = educational escape room. The results of the KAT test revealed significant differences between the control group (CG) (M = 7.17, SD = 1.94) and the experimental group (EG) (M = 8.36, SD = 1.70) (Z = -2.59, p = .01; Cohen’s d = 0.65). These findings indicate that the group that participated in the EER exhibited greater learning compared to the group that underwent the traditional teaching technique. Regarding the comparative analyses between the different structures of the EER, the results showed no significant differences (Z = -1.15, p = .25) between the group that completed the S-EER (M = 8.24, SD = 1.48) and the P-EER group (M = 8.56, SD = 2.03; Cohen’s d = 0.18). Qualitative Results of the Open Questions Interview Difficulty Some students acknowledged a high degree of difficulty. Other participants attributed the difficulty not to the content of the tasks but to the idiosyncrasies of the EER itself, expressing concern about the challenge of finding clues. Among those who consider the activity not to be a difficult challenge, opinions diverge, as some students attribute the ease to having support materials (notes and internet searches), collective thinking (since the activity was carried out in teams), and the support of the teaching staff. Learning Most students acknowledge that they did not learn new concepts, but they did review and solidify the ones they already have. On the one hand, they also feel that the escape room does not allow for the permanent retention of concepts since the pressure of competition caused them to not pay as much attention to learning the concepts as they could have. On the other hand, they recognize that the activity has an impact on their training as psychology professionals, but they are not clear about how they will use the skills practiced in the EER. Teamwork The students assert that the groups were too large, and some participants were unable to have as active a role as they would have liked. Furthermore, on some occasions the groups did not act collectively; instead, members divided tasks, and at times, puzzle-solving ended up being an individual effort. Only one group reports interpersonal conflicts. Regarding group formation, students propose to avoid forming groups based on personal relationships or affinities and to encourage the development of new synergies. General Positive Outcomes The most celebrated aspects of the activity were the dynamism of combining an educational activity with physical movement, feeling stimulated, and the perception of getting closer to psychological reality, as students find themselves in a real situation where they have to deal with diagnoses. Also highlighted as positive aspects are negotiation with the rest of the team, attention to instructions, short and long-term memory, abstract reasoning, the development of mental agility, problem-solving, organization, creativity, and outside-the-box thinking. All individuals interviewed would repeat the activity and express a high level of satisfaction with the escape room experience. General Negative Outcomes It is noted that the excitement of the competition hindered the retention of what they had just experienced. It is explicitly stated: “When we had the results, we didn’t even think about what this disorder is, we were just excited to finish the task, not to know what those little things mean.” They have also mentioned difficulties, such as not finding clues quickly, leading to frustration and being overwhelmed. Finally, the digitization of some tasks has received numerous criticisms, as students lacked in-person guidance from the teaching staff and materials they could touch and share among the entire group. The scanning of a QR code was limited to a few people in the group who then formed small subgroups (due to the visibility of a phone screen), which hindered teamwork. Open Questions to Teachers The teaching team that developed the escape room is gender-balanced, with ages ranging from 34 to 47 years, indicating a relatively young team. None of them have more than 8 years of continuous contractual teaching experience. In terms of personal traits, all of them identify themselves as empathetic or learning companions rather than authoritative figures when asked about their self-perception as educators. A shared perception among them is the demotivation observed in students, particularly in subjects related to neuroscience, as these are more biological and do not meet the clinical expectations with which students begin their psychology education. They all share a concern for offering different activities that motivate students. On the day of the escape room event, difficulties were acknowledged, including the challenge of organizing tasks for very large groups, the absence of students who had committed to attending, varying emotional reactions of students to highly complex tasks, and the difficulty of adapting neuropsychobiological content. There is also a retrospective appreciation for the importance of simplifying tasks and delving into interpersonal experiences during the debriefing to prevent conflicts in the classroom. There is unanimous agreement that the escape room does not fulfill a didactic objective of retaining theoretical knowledge. However, it does provide a new context for teacher-student interaction, one that is more horizontal, relaxed, and enjoyable, and it successfully reconnects and motivates students with the subject. Additionally, the teaching staff gained satisfaction from offering different activities, motivation in their teaching practice, recognition and respect from students, and the encouragement of their creativity. The aim of this study was to analyze the effects of EERs in psychology students on knowledge acquisition, as well as to analyze the effects of different EER designs. The main results showed a positive perception of the activity by the students, greater knowledge acquisition outcomes in the EG, and qualitative data were also collected to gain deeper insights into participants’ and teachers’ experiences. Quantitative results show positive opinions from the students, with a notable emphasis on the perception of EER as a highly engaging activity that fosters the development of teamwork skills. The transferability of skills and the resources used in EER also received positive ratings, although these were the least valued aspects. These findings align with our hypothesis and have been supported by numerous previous studies, confirming that EERs are well-received by students (Prieto et al., 2021, Veldkamp et al., 2020). Similarly, qualitative analysis confirms these results, highlighting that EERs are stimulating, promote learning, and foster cognitive training. However, these results also enable a deeper exploration of certain negative aspects that should be considered when implementing these tools, such as the level of difficulty and group management, including size or potential problems with member interaction. These outcomes were also documented by Hermanss et al. (2018), who reported that students experienced feelings of frustration due to a lack of time, the absence of clear instructions, and the perception that the tasks did not significantly contribute to specific knowledge acquisition. These results underscore the importance of conducting a debriefing session at the end of the activity to evaluate not only the theoretical or cognitive aspects but also any negative elements that may have arisen, such as frustration and communication issues with team members, etc. In a similar vein and according to qualitative results obtained from the teachers, we believe that prior to commencing the activity, students should be informed about potential negative experiences associated with it, including the lack of highly detailed instructions, the inherent difficulty of the activity, and the time constraints and competitiveness. In terms of knowledge acquisition, the results indicate that the EG scored higher than the CG in the KAT test, but no significant differences were found between the types of EER structure. These results indicate that EERs have a more positive impact on knowledge acquisition compared to traditional educational techniques. The limited studies that analyze the impact on knowledge acquisition show an improvement between pre and post-test measures (Aubeux et al., 2020; Dimeo et al., 2022; Eukel et al., 2017; Gordillo et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020), although there are also studies that show no improvement (Clauson et al., 2020) or even a negative impact (Cotner et al., 2018). It is worth noting that, except for the study by Dimeo et al. (2022), the rest of the studies do not include any comparative control group. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, the assessment tests used were the same in the pre and post-test, indicating a potential learning bias in the results. According to Veldkamp et al. (2020), the choice of structure has significant implications for the planning and implementation of this activity by educators. Our initial hypothesis was based on the assumption that P-EERs, which have structural characteristics more similar to ill-structured problems, would require the use of reasoning and problem-solving skills, leading to greater learning outcomes. However, our results do not support our hypothesis, diverging from pedagogical studies that have demonstrated the benefits of using ill-structured problems over well-structured problems in the classroom (Pulgar et al., 2020), indicating that the structure of the escape room does not have significant implications for student learning. One possible explanation is that it may not be the structure of the escape room itself that enhances learning, but rather other factors inherent to the activity, such as its novelty, the group-based format, or the active learning approach. In fact, previous research with Spanish university students has shown that active methodologies are positively perceived both by teachers and students—especially when they understand their purpose—and are considered a better strategy for learning. These methodologies have been found to foster interdisciplinarity and research—skills that go beyond content acquisition and support broader learning processes—while also promoting the development of learning strategies, collaboration, and peer learning (Crisol-Moya et al., 2020). Considering the findings presented and previous studies, it is relevant to acknowledge the limitations of the present study. The sample was convenience-based, which limits the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the opinions, attitudes, and satisfaction with the EER questionnaire was developed ad hoc, potentially affecting the reliability of the satisfaction data. Further, no pilot study was conducted to identify potential difficulties that could have been addressed in advance. Also, no pretest was included to assess the change in knowledge acquisition, which would have given more insights regarding how the students’ knowledge changed pre- and post-EER, while taking into account baseline differences in knowledge Finally, the results should be interpreted considering the difference in duration between the EER and the traditional teaching technique. In a similar vein, the traditional learning technique differs from the EER in aspects such as the absence of hands-on manipulation, group work, and level of activation. In future studies, these variables should be considered to ensure a more precise analysis of the study’s results. Finally, due to sample loss between sessions and differences in sample size, the statistical power of the analyses may be limited, affecting the reliability of the results. In conclusion, our findings offer preliminary evidence that EERs may serve as useful pedagogical tools for undergraduate psychology students. Although future studies should refine the methodological design and control for potential confounding variables, participants in our sample generally found EERs engaging, and their post-test performance showed a tendency toward higher scores than those observed in the traditional learning condition. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Valls-Serrano, C., Moore, H., Rabadán-Pardo, M. J., Egea-Cariñanos, P., & Vélez-Coto, M. (2026). Educational escape room for psychology students: Exploring design structure and effectiveness. Psicología Educativa. 32, Article e260445. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a2 Funding This research received funding from the Catholic University of Murcia (Project number: PID-04/22). References |

Cite this article as: Valls-Serrano, C., Moore, H., Rabadán-Pardo, M. J., Egea-Cariñanos, P., & Vélez-Coto, M. (2026). Educational Escape Room for Psychology Students: Exploring Design Structure and Effectiveness. PsicologĂa Educativa, 32, Article e260445. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a2

Correspondence: htamoore@ucam.edu (H. T. A. Moore).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS