School Anxiety Inventory for Primary Education: Measurement Invariance and Latent Mean Differences in Spanish Children

[Inventario de ansiedad escolar para Educación Primaria: invarianza de medida y diferencias de medias latentes en niños españoles]

María Isabel Gómez-Núñez1, José Manuel García-Fernández2, & Cándido J. Ingles3

1International University of La Rioja (Universidad Internacional de La Rioja), Logroño, La Rioja, Spain; 2University of Alicante, San Vicente del Raspeig, Alicante, Spain; 3Miguel Hernández University, Elche, Alicante, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a3

Received 8 November 2024, Accepted 25 August 2025

Abstract

School anxiety is one of the most prevalent school attendance problems in Spanish children. Despite its importance, no instruments are available for a precise diagnosis and to establish gender and age differences. This study analyzed the measurement invariance and the latent mean differences of the School Anxiety Inventory for Primary Education (SAI-PE) scores across gender and age in a sample of Spanish children. The sample comprised 1,203 children between 8 and 11 years (M = 10.2, SD = 1.32), selected through random sampling. Findings showed that the SAI-PE presents measurement invariance across gender and age in Spanish children. The latent means analysis revealed that girls scored significantly higher than boys on all SAI-PE dimensions. School anxiety was significantly higher among eight-year-old students. The SAI-PE is the only instrument reliably assessing school situations and anxiety responses in the Spanish child population.

Resumen

La ansiedad escolar constituye uno de los problemas de asistencia a niños en edad escolar más prevalentes en población infantil española. A pesar de su importancia, no se dispone de instrumentos que permitan un diagnóstico preciso o la detección de diferencias en función del género y la edad. Este estudio analizó la invarianza de medida y las diferencias de medias latentes en las puntuaciones del Inventario de Ansiedad Escolar en Educación Primaria (IAEP) según el género y la edad en una muestra de niños españoles. La muestra estuvo compuesta por 1,203 escolares de entre 8 y 11 años (M = 10.2, DT = 1.32), elegidos mediante un muestreo aleatorio. Los resultados muestran la invarianza de medida en función del género y la edad en la población infantil española del IAEP. El análisis de medias latentes muestra puntuaciones significativamente más elevadas en las niñas que en los niños en todas las dimensiones del IAEP. Asimismo, la ansiedad escolar es significativamente mayor en los estudiantes de ocho años. El IAEP es el único instrumento que mide de manera fiable las situaciones escolares y las respuestas de ansiedad en la población infantil española.

Palabras clave

Ansiedad escolar, Infancia, EducaciĂłn Primaria, Invarianza de medida, Diferencias de medias latentesKeywords

School anxiety, Childhood, Primary Education, Measurement invariance, Latent mean differencesCite this article as: Gómez-Núñez, M. I., García-Fernández, J. M., & Ingles, C. J. (2026). School Anxiety Inventory for Primary Education: Measurement Invariance and Latent Mean Differences in Spanish Children. PsicologĂa Educativa, 32, Article e260446. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a3

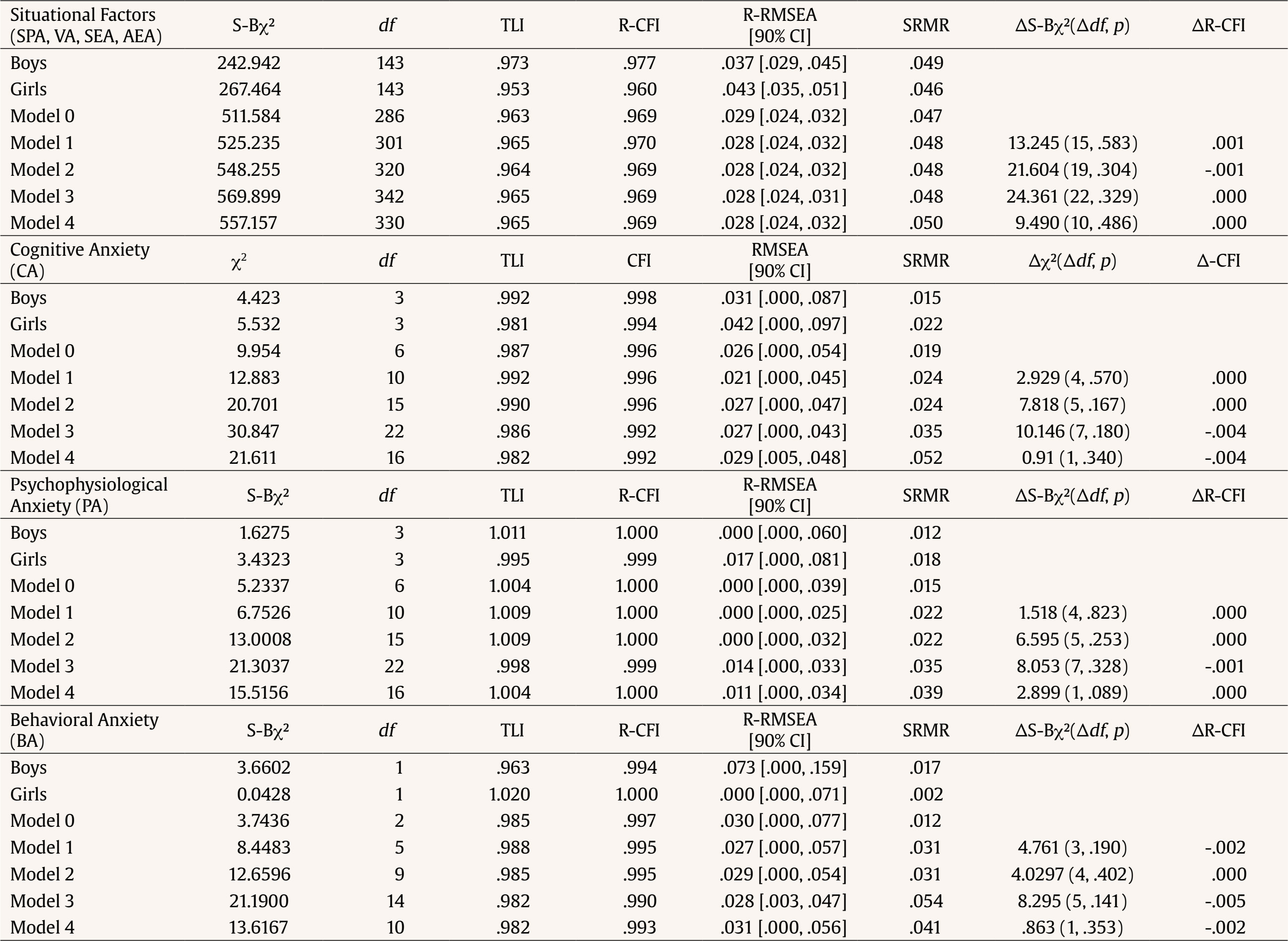

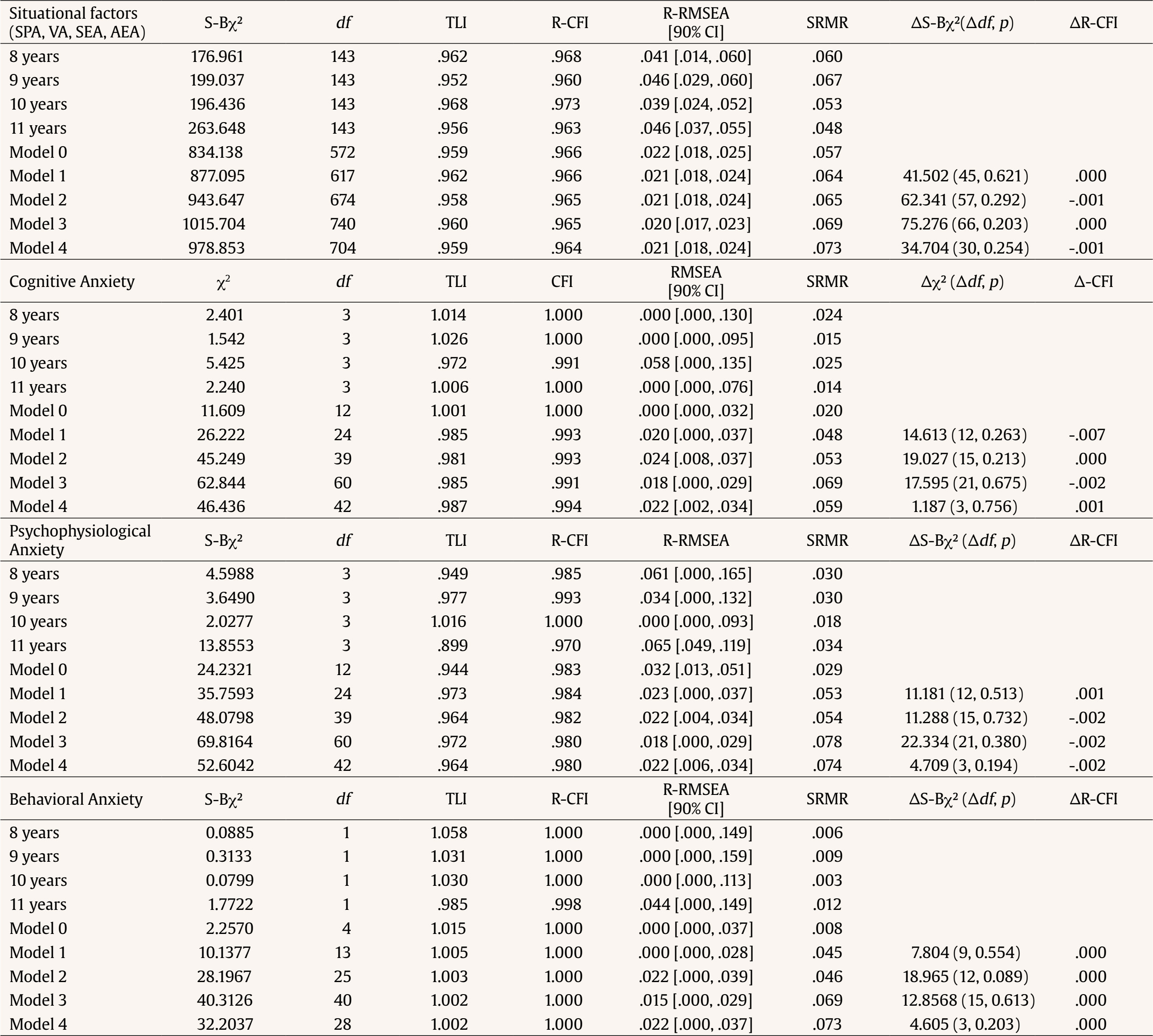

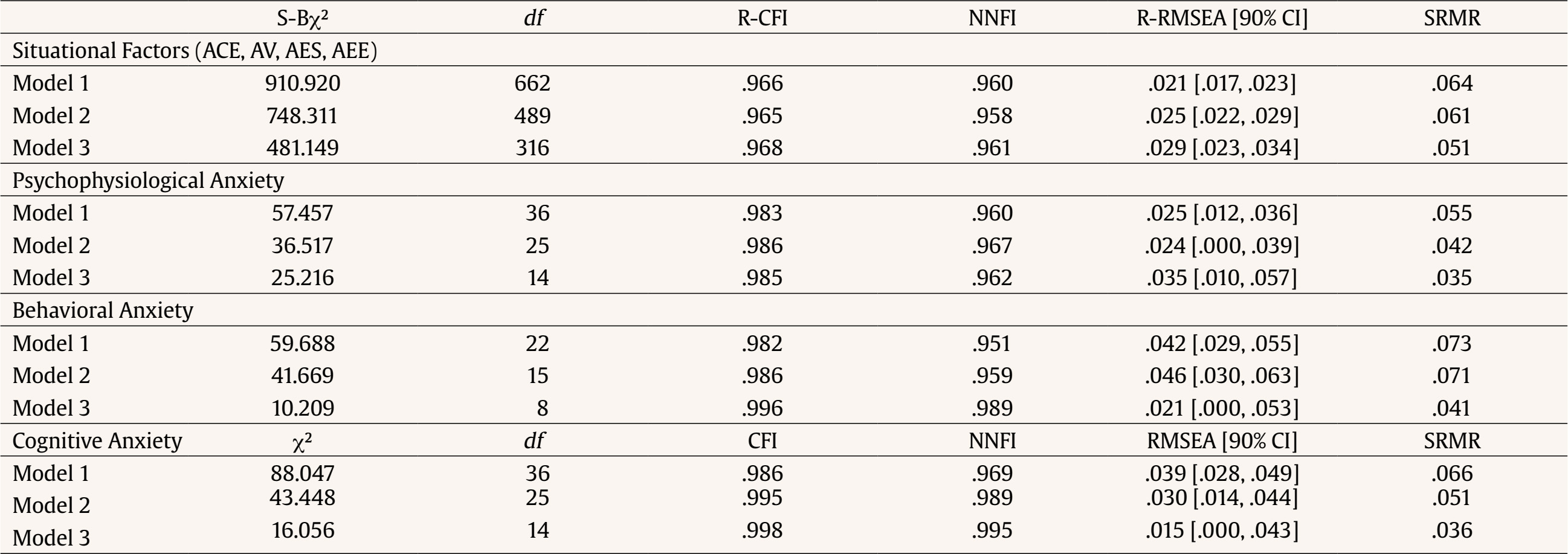

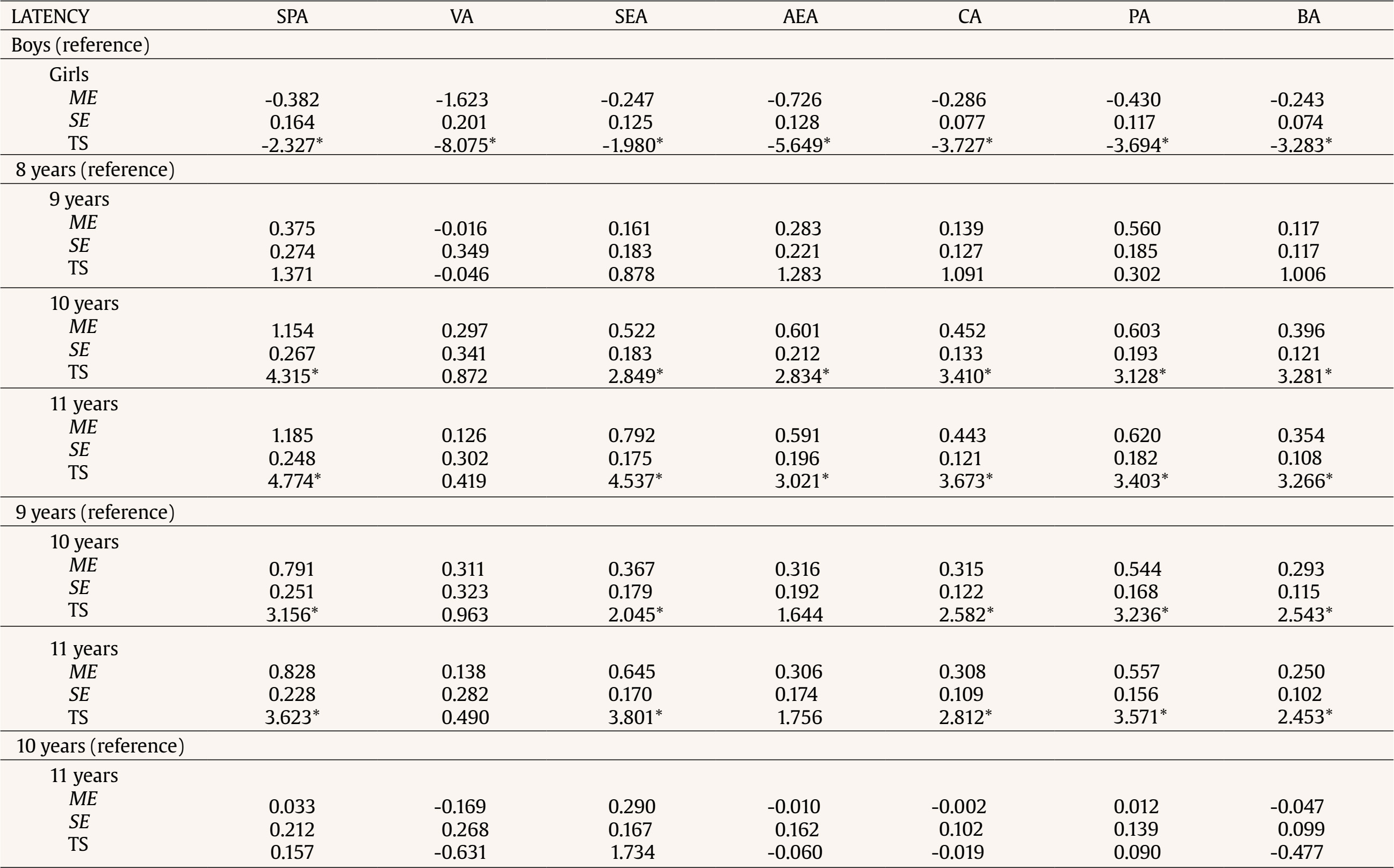

Correspondence: mariaisabel.gomez@unir.net (M. I. Gómez-Nuñez).School attendance problems are among the most concerning phenomena in the Spanish child population (Cruz Orozco, 2020; Martínez-Torres et al., 2024). Current studies show that between 3% and 7.2% of students in compulsory education miss school one or more times per week (Cruz Orozco et al., 2025; Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional [Ministry of Education and Vocational Training], 2021). Despite advancements in early education and increased funding policies in education, Spain has a higher grade retention rate than the average of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Union (EU), with early school dropout as one of its greatest challenges (Ministerio de Educación, Formación Profesional y Deportes [Ministry of Education, Training, and Sports], 2024). School anxiety is among the main school attendance problems, with an approximate prevalence of 38.2% in the Spanish child population (Fernández-Sogorb et al., 2021). School anxiety is defined as an emotional response characterized by cognitive, psychophysiological, and motor reactions that occur in response to school situations perceived by the individual as threatening or ambiguous, even if they are not objectively so (García-Fernández et al., 2024; García-Fernández & Ingles, 2017; Ingles et al., 2015). School anxiety is one of the main causes of school refusal and absenteeism in childhood (Gonzálvez et al., 2018; Tekin & Aydın, 2022), as well as of academic problems such as maladaptive perfectionism or academic underachievement (Ingles et al., 2016; Ula & Seçer, 2024; Zuppardo et al., 2020) and socio-emotional issues like bullying or aggressiveness (Escortell et al., 2020; Torregrosa et al., 2020). Despite the importance of school anxiety and its multiple negative consequences, educators and educational psychologists lack the instruments to make a precise diagnosis and establish gender and age differences in this emotional response. This study aims to fill this gap in school anxiety practice and research in the Spanish child population. Early assessments facilitate the planning and development of preventive interventions for emotional problems (Pérez Marco et al., 2024). School Anxiety Inventory for Primary Education (SAI-PE) The SAI-PE, an instrument to assess school anxiety in children, is grounded in the principles of Lang’s (2010) three-dimensional theory and Endler’s (1981) interactionist theory. It is an adaptation to children of the School Anxiety Inventory for Adolescents-Short Version (SAI-SV; García Fernández & Ingles, 2017; Ingles et al., 2015). The SAI-PE was adapted and validated in a sample of 843 Spanish students aged 8 to 11 (García-Fernández et al., 2024). Its multidimensional structure includes three factors related to the triple response system of anxiety (cognitive, psychophysiological, and behavioral) and the four dimensions that define the school situations that could provoke this emotion (school punishment, victimization, social evaluation, and academic evaluation). Previous studies conducted in Spain have administered the SAI-PE to examine its relationship with variables such as cyberbullying (Delgado et al., 2019), school refusal (Gómez-Núñez et al., 2017; Gonzálvez et al., 2018), or aggressiveness (Torregrosa et al., 2020). However, those studies did not analyze the equivalence of the items’ meaning in the different groups evaluated. The invariance analysis of a measurement instrument is essential to ensure that the items are interpreted in the same way, regardless of the analyzed sample (Yuan & Chang, 2016). School Anxiety Differences across Gender and Age The prevention or treatment of school anxiety in childhood requires the analysis of personal factors, such as gender and age, which could determine differences in the expression of this emotion. Concerning gender differences, in a sample of Spanish children aged 8 to 11, Gómez-Núñez et al. (2017) observed that girls obtained a significantly higher mean than boys in school anxiety. This study also revealed an increase in school anxiety levels around 10-11 years, coinciding with the stage before the transition to secondary education. This study used observed means, but latent means reflect true differences more accurately than observed means because they are not identified with measurement error (Brown, 2006b). In this regard, Fernández-Sogorb et al. (2018), using latent mean analysis, did not find statistically significant differences in school anxiety by sex in a sample of Spanish children aged 8 to 12. However, this study did report a significant increase in school anxiety (both anticipatory and general school anxiety) among students aged 10-11 compared to students aged 8-9. Notably, this analysis did not consider the tripartite response system that characterizes this emotional construct, nor the specific school-related situations that might elicit its manifestation. Given the variability in findings depending on the analytical approach used, the present study seeks to offer a more comprehensive and refined explanation that contributes to a deeper understanding of sex- and grade-related differences in school anxiety, specifically, employing latent mean analysis while accounting for the multidimensional nature of school anxiety (i.e., cognitive, psychophysiological, and behavioral response systems), as well as the school-related factors that influence its onset and/or maintenance. This would constitute a theoretical and practical contribution to the conceptualization and management of this emotional response among Spanish school children. The Present Study The use of validated instruments in the Spanish child population, which take into account the complexity of the school anxiety response, is essential for planning and implementing preventive and therapeutic interventions in educational contexts. So far, only the SAI-PE is available to comprehensively assess school anxiety in Spanish children. However, the lack of invariance analysis hinders the determination of gender and age differences, as well as the accurate diagnosis of each child’s actual symptoms. Therefore, the main goal of this study was to analyze the measurement invariance and latent mean differences in the SAI-PE scores across gender and age in a sample of Spanish children. The specific aims are: (1) to confirm the multidimensional structure of school anxiety situations and responses of the SAI-PE as identified in the original validation (García-Fernández et al., 2024); (2) to assess the measurement invariance of the SAI-PE scores across gender and age; and (3) to identify latent mean gender and age differences in the diverse SAI-PE factors and total score. Based on previous research with Spanish children, we expected the following results: (1) the SAI-PE would exhibit a multifactorial structure for school-related situations; (2) the SAI-PE would show a multifactorial structure for the school anxiety responses examined (i.e., cognitive, psychophysiological, and behavioral); (3) the SAI-PE structure would remain invariant across gender and age; (4) gender differences would emerge in the respective SAI-PE factors when using latent means; and (5) the highest levels of school anxiety would be observed in the 10-11 age group, also using latent mean analysis. Participants Random cluster sampling was used to select three schools for each of its five geographical areas in the province of Alicante (Spain). A total of 15 schools were selected, 10 of which were public and 5 were subsidized (i.e., private schools receiving public funding from the Spanish government). Four classrooms were randomly chosen from each school (one classroom from each grade from 3rd to 6th grade of Primary Education), with an average of 21 students per class. The initial sample comprised 1,260 students, 11 (0.87%) of whom were excluded due to lack of informed consent from parents or legal guardians, 7 (0.55%) because of the lack of knowledge of Spanish, and 39 (3.09%) as outliers and missing data. The final sample included 1,203 children (57.7% girls) from Primary Education (3rd grade = 19.1%, 4th grade = 20.5%, 5th grade = 28.4%, and 6th grade = 31.9%), aged between 8 and 11 (M = 10.2, SD = 1.32). Instrument The School Anxiety Inventory for Primary Education (SAI-PE; García-Fernández et al., 2024) is an adaptation of the SAI-SV (García-Fernández & Ingles, 2017). It is a self-report that assesses school anxiety in children aged 8 to 11. The inventory presents 19 items grouped into four factors referring to situations that can cause anxiety: (I) School Punishment Anxiety (SPA) refers to the anxiety experienced in situations of direct punishment at school or situations that may result in disciplinary action (5 items; e.g., “If the teacher scolds me or rebukes me”); (II) Victimization Anxiety (VA), which measures the anxiety arising from situations where an individual feels targeted or attacked by peers (5 items; e.g., “If a classmate tries to force me to do things I don’t want to do”); (III) Social Evaluation Anxiety (SEA), related to the anxiety felt when expecting others’ negative judgment in a school setting (5 items; e.g., “If I have to explain a class assignment”); and (IV) Academic Evaluation Anxiety (AEA), which measures the anxiety felt in examination situations (5 items; e.g., “A few moments before taking an exam”). In addition, the SAI-PE includes 14 items grouped into the three anxiety response systems: Cognitive Anxiety (CA; 5 items; e.g., “I’m worried”), Psychophysiological Anxiety (PA; 5 items; e.g., “My heart beats very fast”), and Behavioral Anxiety (BA; 5 items; e.g., “My voice is shaky”). García-Fernández et al. (2024) validated the SAI-PE scores through exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), obtaining adequate internal consistency indices (Cronbach alpha) for the total scale (α = .92), the four situational factors, and the three anxiety responses (α = .80-.90). The correlations between the various situational factors ranged from moderate to high (r = .35-.55). The correlations between the different anxiety response scales ranged between .70 and .79, considered high magnitude. Procedure First, the selected schools’ principals, headmasters, and teachers were interviewed by researchers. Following this, an informational letter was sent to the students’ families to describe the study and request their written informed consent. The instrument was then administered voluntarily, collectively, and anonymously in the classroom to all the children who finally participated in the research. Participants provided basic sociodemographic information as required by the assessment instruments (i.e., sex, academic grade, etc.) and responded to the items included in those measures. This research protocol was approved by the ethical committees of the universities involved in the study (UA-2019-07-10). All participation and procedures followed the ethical guidelines of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later revisions (World Medical Association., 2013). Data Analysis Concerning the first specific objective of this research, several confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were performed to assess the internal structure of the SAI-PE. The polychoric correlation matrix was examined using weighted least squares (WLS) to estimate the parameters of the CFA models. Subsequently, the normality of the SAI-PE distribution was examined, both for school situations and anxiety responses. For this purpose, univariate skewness, univariate kurtosis, and multivariate kurtosis values (Mardia coefficient) were obtained. If the Mardia coefficient exceeded the maximum value of 5, it was assumed that there was no multivariate normality in the data (Bentler, 2005), and the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square (S-Bχ²) (Satorra & Bentler, 2001) was used, following the recommendations of Finney and DiStefano (2006). In addition, due to the chi-square’s sensitivity to sample size (which can be significant in large samples even when the data fit the model appropriately), the following fit indices were also used: the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < .08 reasonable fit; < .05 good fit), the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR < .08 acceptable fit; < .05 good fit ), the comparative fit index (R-CFI > .90 acceptable fit; > .95 good fit), and the Tucker Lewis index (TLI > .90 good fit) (Brown, 2006a; Hu & Bentler, 1999). For cases in which the normality of the SAI-PE distribution was rejected, the robust goodness-of-fit indices R-RMSEA, SRMR, R-CFI, and TLI were used with the same limits. To address the second specific objective of this study, multigroup confirmatory factor analyses (MGCFA) were performed to examine the measurement invariance of the SAI-PE scores across gender and age. Following the indications of various researchers (e.g., Byrne, 2008; Dimitrov, 2010; Yuan & Chan, 2016), the multifactorial model for school anxiety situations and responses was tested in each gender and age group to analyze configural invariance (Model 0). Subsequently, measurement invariance was examined based on: (a) the equality of factor loadings across groups (Model 1: metric invariance), (b) the item intercept equality across groups (Model 2: strong or scalar invariance), and (c) the equality of item error variance/covariance across groups (Model 3: strict or uniqueness invariance). Lastly, structural invariance was evaluated based on the invariance of factor variances and covariances (Model 4). Δ-CFI and ΔR-CFI (< -.01), and Δχ² and ΔS-Bχ² (nonsignificant p) were used to check model equivalence (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). Byrne (2008) recommended using the Lagrange multipliers method to determine which constraints can be removed to improve a model’s fit. To achieve the third specific objective of this research, latent mean analyses were conducted on the various factors and the total SAI-PE score. In the latent mean analysis, the group of boys and the 8-, 9-, and 10-year-olds were used as reference groups (set at 0). The variance of the means was evaluated using the critical ratio (CR). A CR value greater than 1.96 or less than -1.96 indicates a lack of equality (Tsaousis & Kazi, 2013). All analyses were conducted using the EQS 6.1 software (Bentler, 2005). Confirmatory Factor Analysis for the Situational Factors and Responses of the SAI-PE For situational factors, the Mardia coefficient was 59.1549, showing no multivariate normality in the data. The results indicated that the four-factor correlated model (SPA, VA, SEA, and AEA) presented adequate fit to the data, as indicated by the fit indices used (S-Bχ² = 372.033, R-RMSEA = .041, 90% CI [.036, .046], SRMR = .042, R-CFI = .971, TLI = .965). This model showed correlations between the errors of Items 12 and 13 (SPA), 18-21 (VA), and 19-20 (VA). Concerning the dimensions associated with school anxiety responses, the findings revealed multivariate normality for CA (Mardia coefficient = 4.1685). Therefore, the chi-square test (χ²) and the corresponding fit indices were used. The one-factor model fit the data adequately (χ² = 3.554, RMSEA = .014, 90% CI [.000, .058], SRMR = .011, CFI = .999, TLI = .998), with correlations between the errors of Items 1-3 and 4-5. For the PA response, the Mardia coefficient was 19.0723, showing no multivariate normality in the data distribution. The model that best fit the data was the one-factor model (S-Bχ² = 4.177, R-RMSEA = .020, 90% CI [.000, .061], SRMR = .013, R-CFI = .998, TLI = .995), with correlations between the errors of Items 1-3 and 4-5. The lack of multivariate normality was also observed in the BA response (Mardia coefficient = 13.3674). As in the previous responses, the one-factor model showed the best fit to the data (S-Bχ² = 2.874, R-RMSEA = .044, 90% CI [.000, .107], SRMR = .010, R-CFI = .997, TLI = .984), with a correlation between the errors of Items 1 and 2. Measurement Invariance of SAI-PE across Gender: Situational Factors and School Anxiety Responses Table 1 presents the results of the measurement and structural invariance analyses across gender for situational factors and school anxiety responses as measured with the SAI-PE. Table 1 Fit Indices for Situational Factors and School Anxiety Responses by Gender   Note. Model 0 = unconstrained model; Model 1 = Model 0 with factor loads; Model 2 = Model 1 with intercepts; Model 3 = Model 2 with variances and covariances of errors; Model 4 = Model 2 with factor variance; χ2 = Chi-square; S-Bχ2 = Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2; df = degrees of freedom; TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index; CFI = comparative fit index; R-CFI = robust comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; R-RMSEA = robust root mean square error of approximation; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual; ΔCFI = comparative fit index difference test; ΔR-CFI = robust comparative fit index difference test; Δχ² = χ² model comparison test difference; ΔS-Bχ² = χ² model comparison test difference; Δdf = difference between degrees of freedom; SPA = School Punishment Anxiety; VA = Victimization Anxiety; SEA = Social Evaluation Anxiety; AEA = Academic Evaluation Anxiety. Concerning the situational factors, as the Mardia coefficients were 31.4952 (boys) and 51.5615 (girls), robust maximum likelihood estimators were used to fit the measurement model. These robust indices were also used to analyze the PA scores, as the Mardia coefficients were 6.4763 (boys) and 24.3364 (girls). For CA, the Mardia coefficients were 0.1898 (boys) and 3.3710 (girls), so multivariate normality was assumed for the observed measures. The values of ΔR-CFI (< -.01) and Δ-CFI ( < -.01), and the probability linked to ΔS-Bχ² (> .05) and Δχ² (> .05) showed that the different nested models were equivalent to each other as a function of gender. Factorial Invariance of the IAEP across Age: Situational Factors and School Anxiety Responses Table 2 presents the results of the measurement and structural invariance analyses across age for the situational factors and school anxiety responses as evaluated by the SAI-PE. Table 2 Fit Indices for Situational Factors and School Anxiety Responses by Gender   Note. Model 0 = unconstrained model; Model 1 = Model 0 with factor loads; Model 2 = Model 1 with intercepts; Model 3 = Model 2 with variances and covariances of errors; Model 4 = Model 2 with factor variance; χ2 = Chi-square; S-Bχ2 = Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2; df = degrees of freedom; TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index; CFI = comparative fit index; R-CFI = robust comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; R-RMSEA = robust root mean square error of approximation; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual; ΔCFI = comparative fit index difference test; ΔR-CFI = robust comparative fit index difference test; Δχ² = χ² model comparison test difference; ΔS-Bχ² = χ² model comparison test difference; Δdf = difference between degrees of freedom; SPA = School Punishment Anxiety; VA = Victimization Anxiety; SEA = Social Evaluation Anxiety; AEA = Academic Evaluation Anxiety. For situational factors, as the Mardia coefficients were 22.3167 (8 years), 23.2079 (9 years), 23.7254 (10 years), and 30.9926 (11 years), robust maximum likelihood estimators were used for the fit of the measurement model. These robust indices were also used to analyze the PA scores, as the Mardia coefficients were 13.2031 (8 years), 9.7044 (9 years), 7.2972 (10 years), and 9.4384 (11 years), and the BA scores, which presented Mardia coefficients of 11.9990 (8 years), 8.4161 (9 years), 5.2736 (10 years), and 5.7785 (11 years). Concerning CA, the Mardia coefficients were 2.2941 (8 years), 4.0531 (9 years), 1.6608 (10 years), and .6559 (11 years), so the chi-square test (χ²) was used. The values of ΔR-CFI ( < -.01) and Δ-CFI ( < -.01), and the probability linked to ΔS-Bχ² (> .05) and ΔS-χ² (> .05) showed that the different nested models were equivalent to each other as a function of age. Latent Mean Differences across Gender and Age The comparison model used boys as the reference group, setting the boys’ latent means to 0, while the girls’ means were estimated freely. For age comparisons, three models were created due to the presence of four age groups (8, 9, 10, and 11 years). In each model, the youngest group was set to zero as the reference: Model 1 compared 8-year-olds with 9-, 10-, and 11-year-olds; Model 2 compared 9-year-olds with 10- and 11-year-olds; and Model 3 compared 10-year-olds with 11-year-olds. For the groups according to gender, the fit of the statistics for the latent mean structure was appropriate: S-Bχ² = 527.711, df = 316, p < .000, R-CFI = .970, NNFI = .965, R-RMSEA = .027, 90% CI [.023, .031], SRMR = .048 (SPA, VA, SEA, AEA); χ² = 78.827, df = 14, p < .000, CFI = .988, NNFI = .970, RMSEA = .06, 90% CI [.055, .084], SRMR = .044 (CA); S-Bχ² = 78.737, df = 14, p < .000, R-CFI = .998, NNFI = .995, R-RMSEA = .069, 90% CI [.054, .084], and SRMR = .032 (PA); S-Bχ² = 35.720, df = 8, p < .000, R-CFI = .994, NNFI = .980, R-RMSEA = .060, CI [.041, .080], SRMR = .036 (BA). For the age groups, the fit of the statistics for the latent mean structure was appropriate in all cases (see Table 3). Table 3 Fit of the Statistics for the Latent Mean Structure of the Age Groups in the Dimensions of the SAI-PE   Note. S-Bχ2 = Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2; df = degrees of freedom; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; R-CFI = robust comparative fit index; R-RMSEA = robust root mean square error of approximation; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual; SPA = School Punishment Anxiety; VA = Victimization Anxiety; SEA = Social Evaluation Anxiety; AEA = Academic Evaluation Anxiety; Model 1 = 8 versus 9, 10, 11 years; Model 2 = 9 versus 10, 11 years; Model 3 = 10 versus 11 years. As shown in Table 4, there were statistically significant differences for the four situational factors and school anxiety responses included in the SAI-PE: SPA (TS = -2.327), VA (TS = -8.075), SEA (TS = -1.980), AEA (TS = -5.649), CA (TS = -3.727), PA (TS = -3.694), and BA (TS = -3.283). Table 4 Latent Mean Difference across Sex and Age in Situational Factors and Responses to the SAI-PE   Note. ME = mean estimate; SE = standard error; TS = test statistic; SPA = School Punishment Anxiety; VA = Victimization Anxiety; SEA = Social Evaluation Anxiety; AEA = Academic Evaluation Anxiety; CA = Cognitive Anxiety; PA = Psychophysiological Anxiety; BA = Behavioral Anxiety. *p < .05. However, when comparing the different age groups, we found no statistically significant differences in the various dimensions of the SAI-PE between 8- and 9-year-old students. In contrast, the 8-year-olds scored significantly higher than the 10- and 11-year-olds on all the dimensions of the SAI-PE, except for the VA factor. The 9-year-olds scored significantly higher than the 10- and 11-year-olds on the SPA, SEA, CA, PA, and CA factors but not on the VA and AEA factors, where no statistically significant differences were found. Finally, we detected no statistically significant differences between the 10- and 11-year-old age groups. The analyses allowed us to examine the measurement invariance and latent mean differences of the SAI-PE based on gender and age in the Spanish child population and investigate the hypotheses outlined at the beginning of this work. The results confirmed the first two hypotheses, showing that the SAI-PE has a multifactorial structure for school situations and anxiety responses, consistent with its initial validation (García-Fernández et al., 2024) and the original adolescent version (García Fernández & Inglés, 2017; Ingles et al., 2015). Situations involving academic and social evaluation, victimization, and school punishment were identified as key triggers of this emotional response (García-Fernández et al., 2024; Gómez-Núñez et al., 2017; Ingles et al., 2015). These findings connect with Endler’s (1981) interactionist theory, indicating that in assessing school anxiety, it is not only necessary to consider the characteristics of the evaluated subject or the type of reactivity pattern expressed. The situations in which this emotion manifests are essential in evaluating its different manifestations. Additionally, in line with Lang’s (2010) three-dimensional theory, the construct’s multidimensionality was confirmed, highlighting that cognitive, psychophysiological, and behavioral responses can operate independently and also interact with each other. Therefore, a person may exhibit a reactivity pattern in which one response predominates (e.g., cognitive response) while the other responses (e.g., behavioral and psychophysiological responses) may remain at lower activation levels. The third hypothesis was confirmed, as the multidimensional structure of the situational and school anxiety responses of the SAI-PE was invariant across gender and age. These data are consistent with previous studies on the SAI-SV, which also demonstrated an invariant structure in the adolescent population (García Fernández & Ingles, 2017; Ingles et al., 2015). Measurement invariance analysis is a key aspect in understanding the functioning of the items that comprise the instruments used for psychological and educational assessment (Dimitrov, 2010; Yuan & Chang, 2016). The absence of such analyses would hinder the study of differences in different population groups, as it would be unclear how the participants interpret the administered tests. The results obtained from the invariance analyses of the SAIPE, based on gender and age indicate that primary school children, regardless of their gender or age group, interpret the meaning of the items in this instrument in the same way. The fourth hypothesis, concerning the existence of statistically significant gender differences in the latent means of the SAIPE factors, was confirmed. Girls showed higher levels of school anxiety for all SAI-PE factors. Previous studies indicate the importance of boys’ and girls’ differential socialization processes or psychological variables as possibly underlying these differences (Gómez-Núñez et al., 2017; Ingles et al., 2015). Girls may feel freer to express emotions such as anxiety, which is often compounded by the overprotection exercised by their caregivers, as well as the social pressure many girls face to meet academic standards or expectations (Catheline, 2019). On the other hand, boys may suppress emotions that are considered signs of weakness and lack of courage, such as anxiety. Similarly, pubertal changes or the presence of cognitive distortions may increase the risk of manifesting anxiety in educational contexts (for a review, see Hallers-Haalboom et al., 2020). Finally, the last hypothesis was not confirmed, as higher levels of school anxiety were found at 8-9 years of age for all the factors, except for anxiety in the face of victimization, which was stable over time. The change in the educational cycle that occurs at these ages, following Spanish regulations, and the increase in school stress levels (Fernández-Sogorb et al., 2021), or the attempt to meet teachers’ and parents’ expectations (Catheline, 2019) may explain these findings. Moreover, it is important to consider factors such as school refusal, which may increase around ages 8-9 (Gonzálvez et al., 2016). In this regard, recent reviews emphasize the relevance of addressing school refusal behavior from early childhood, not only due to its prevalence during the initial years of formal education, but also as a preventive measure against the increase of socioemotional problems (Kearney et al., 2023; Ula & Seçer, 2024). Additionally, situations involving bullying and school aggression may impact children similarly, regardless of age, which could help explain the present study’s findings related to victimization anxiety (Delgado et al., 2019; Escortell et al., 2020; Torregrosa et al., 2020). More studies are needed in this line, including other Spanish geographical areas, to expand and specify these findings. Limitations and Implications for Future Research Despite this study offering new and valuable insights into the psychometric properties of the SAI-PE, these results should be interpreted in light of some limitations to be considered in future research lines. Firstly, the SAI-PE should contain clinical cut-off points establishing diagnostic performance curves or ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic), using parameters such as sensitivity and specificity (Roy-García et al., 2023). This would allow the classification of children with high, moderate, or low school anxiety, which would facilitate designing a profile sheet to quickly and graphically capture these cut-off points. Secondly, the results of this study were extracted from community samples of Spanish children. Therefore, the results of this research should be replicated in clinical samples of children to rigorously compare the prevalence rates of school anxiety in the two samples. Moreover, the findings were obtained with a sample of primary school children aged 8 to 11. It would be interesting to identify the type and level of school anxiety prevailing in the first cycle of Primary Education (children aged 6-7 years) to analyze whether gender differences and changes due to the first years of compulsory school in Spain are maintained. Thirdly, the results of this study cannot be applied to other ethnicities/cultures, considering the significant cross-cultural differences in general anxiety and school anxiety in particular (e.g., Torregrosa et al., 2022). Enhancing the representativeness of the study sample through greater geographical diversity would allow for more thorough comparisons and facilitate the identification of potential patterns based on participants’ regional backgrounds. It would be useful to examine the convergent validity of the SAI-PE with instruments that assess school anxiety (e.g., VAA-R; Fernández-Sogorb et al., 2018), as well as its divergent validity with measures that evaluate different but related variables to school anxiety (e.g., school stress, separation anxiety, etc.). Finally, in future research, the perceptions of the families and teachers should be considered, as well as the joint use of other techniques and instruments to assess school anxiety in childhood. This would help address the limitations of self-report measures in evaluating anxiety (Etkin et al., 2021) and allow for adopting a multimethod and multisource perspective to assess this emotional response. Practical and Research Implications Measurement invariance analysis is an essential procedure in the construction and validation of instruments applied in the fields of psychology and education. Reviews like that by Putnick and Bornstein (2016) highlight the importance of demonstrating measurement invariance as a prerequisite for studying developmental changes and comparing measures and relationships between groups. The absence of measurement invariance would indicate differential item functioning (DIF), suggesting that the responses provided relate differently to the latent variable depending on the studied population group (Belzak & Bauer, 2020; Zwick, 2014). Without this type of analysis, it would not be possible to assert that a construct is understood in the same way across different groups of people (Schmitt & Ali, 2015; Yuan & Chan, 2016). Thus, the support for the measurement invariance of the SAI-PE demonstrated through this study justifies comparing school anxiety levels based on gender and age in Spanish children. This is a key factor, as gender and age are important moderating variables in the effectiveness of preventive and therapeutic programs for emotional disorders in childhood (Diego et al., 2024; Essau et al., 2019). When applying the SAI-PE, educators and educational psychologists should examine both the scores related to situational factors (school punishment, victimization, social, and academic evaluation) and the reactivity patterns exhibited by each child (cognitive, psychophysiological, and behavioral reactions). This detailed analysis would allow determining which situations are most anxiety-provoking for each individual and how school anxiety manifests based on the reactions displayed. The confirmation of measurement invariance serves as essential evidence that the items are interpreted in the same way, regardless of the age group or gender of the evaluated students. This would enable a more precise, effective, and reliable diagnosis. Therefore, the analysis of measurement invariance of the SAI-PE allows researchers to learn more about the construct of school anxiety and gain a deeper understanding of the differences between the various groups studied. Furthermore, the findings obtained in this research also have important implications for clinical and educational practice. Specifically, in Spain there is considerable concern about the prevalence of school anxiety following the Covid pandemic, with a rate of about 38.2%, especially due to its relationship with school refusal and dropout (Gonzálvez et al., 2018; Ula & Seçer, 2024). In this regard, the SAI-PE emerges as an instrument that can be administered easily and collectively in clinical and educational settings, providing an exhaustive measure of school anxiety manifested by Spanish primary school children. The SAI-PE offers interesting advantages compared to other self-reports based on a unidimensional perspective of school anxiety, or those that focus solely on one reaction (e.g., cognitive or psychophysiological) while overlooking the school situations that provoke it. Establishing the individual pattern of school anxiety reactivity based on the school situation where it manifests would optimize the psychological and educational response provided (Torregrosa et al., 2020). Based on their scores, preventive programs such as those established for the treatment of problems like school anxiety, school refusal, and truancy (Galán-Luque, 2023; Pérez Marco et al., 2025; Ula & Seçer, 2024), emotion self-regulation or anxiety reduction (Diego et al., 2024; Essau et al., 2019; Mahdi et al., 2019; McDonald et al., 2024; Nieto-Carracedo et al., 2024; Usta & Inozu, 2024) could be planned and implemented as of early childhood. When planning these programs, practitioners should pay special attention to girls and younger students (8-9 years old), as these groups are at higher risk of school anxiety. Similarly, the most anxiety-provoking situations and the manifested reactivity pattern should be considered to select the most effective activities or forms of intervention for each case (for a review, see Pérez Marco et al., 2024). This would also enable us to enhance the socio-emotional well-being of Spanish children. The SAI-PE is the only validated instrument in Spain that provides a comprehensive assessment of school anxiety in children. The measurement invariance of this instrument enhances its potential for analyzing differences between different gender and age groups. In turn, it allows identifying at-risk groups and preventing clinical levels of school anxiety by following up the pattern of reactivity and the school situation in which anxiety manifests. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Acknowledgments This study was supported by the Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) with the grant number RTI2018-098197-B-I00, awarded to the second author. We thank all the schools participating in this study for their collaboration. Cite this article as: Gómez-Núñez, M. I., García-Fernández, J. M., & Ingles, C. J. (2026). School anxiety inventory for primary education: Measurement invariance and latent mean differences in Spanish children. Psicología Educativa, 32, Article e260446. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a3 References |

Cite this article as: Gómez-Núñez, M. I., García-Fernández, J. M., & Ingles, C. J. (2026). School Anxiety Inventory for Primary Education: Measurement Invariance and Latent Mean Differences in Spanish Children. PsicologĂa Educativa, 32, Article e260446. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a3

Correspondence: mariaisabel.gomez@unir.net (M. I. Gómez-Nuñez).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS