Comparative Study of Executive Functioning in Schoolchildren with Dyslexia, Dyscalculia, and Comorbidity of Both Disorders

[Estudio comparativo del funcionamiento ejecutivo en escolares con dislexia, discalculia y comorbilidad de ambos trastornos]

Danilka Castro Cañizares1, 2, Tatiana Mazuera Velázquez3, & Nancy Estévez Pérez4

1Escuela de PsicologĂa, Facultad de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Mayor, Chile; 2Centro de InvestigaciĂłn Avanzada en EducaciĂłn, Universidad de Chile, Chile; 3Escuela de PsicologĂa, Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud y Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de las AmĂ©ricas, Chile; 4Departamento de Neurodesarrollo Infantil, Centro de Neurociencias de Cuba, Cuba

https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a4

Received 28 November 2024, Accepted 25 August 2025

Abstract

Current theories on the origin and development of specific learning disabilities (SLD) suggest that changes in general cognitive abilities, such as executive function, are associated with the onset of both dyslexia and dyscalculia. In this study, the executive functions of primary school children diagnosed with dyslexia, dyscalculia, a comorbidity of both disorders, and without learning difficulties were analyzed. The executive functions of visuospatial working memory, inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, and fluid intelligence were assessed. The results showed significantly lower performance in executive functions in SLD groups compared to the control group, but no significant differences were found between the groups diagnosed with SLD, only in cognitive flexibility between children with dyslexia and children with dyscalculia. These findings support the theoretical hypothesis that the onset and development of SLD is associated with deficits in executive functioning.

Resumen

Las teorías actuales sobre el origen y el desarrollo de los trastornos específicos del aprendizaje (TEAp) proponen que las alteraciones en las capacidades cognitivas de dominio general, como las funciones ejecutivas, se asocian a la aparición tanto de dislexia como de discalculia. En este estudio se analiza el funcionamiento ejecutivo de escolares de Primaria diagnosticados de dislexia, discalculia o comorbilidad de ambos trastornos y de escolares sin dificultades en el aprendizaje. Se evaluaron las funciones ejecutivas de memoria de trabajo visoespacial, control inhibitorio, flexibilidad cognitiva e inteligencia fluida. Los resultados mostraron un rendimiento significativamente inferior en el funcionamiento ejecutivo en los grupos con TEAp con respecto al grupo control, pero no se encontraron diferencias significativas entre los grupos cuyo diagnóstico era TEAp, solo en flexibilidad cognitiva entre los niños con dislexia y los niños con discalculia. Los resultados respaldan la hipótesis teórica de que la aparición y el desarrollo de los TEAp están asociados con déficits en el funcionamiento ejecutivo.

Palabras clave

Dislexia, Discalculia, Comorbilidad, Memoria de trabajo, InhibiciĂłn, Flexibilidad cognitiva, Razonamiento fluidoKeywords

Dyslexia, Dyscalculia, Comorbidity, Working memory, Inhibition, Cognitive flexibility, Fluid reasoningCite this article as: Cañizares, D. C., Velázquez, T. M., & Pérez, N. E. (2026). Comparative Study of Executive Functioning in Schoolchildren with Dyslexia, Dyscalculia, and Comorbidity of Both Disorders. PsicologĂa Educativa, 32, Article e260447. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a4

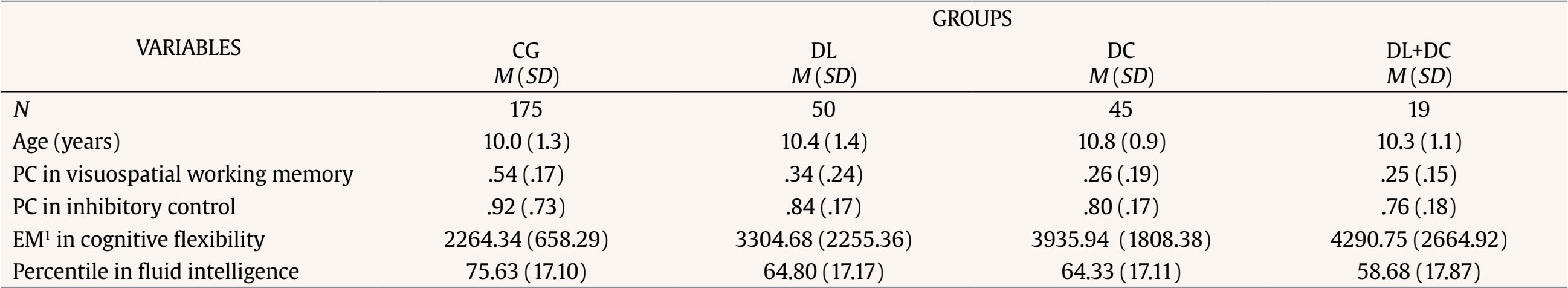

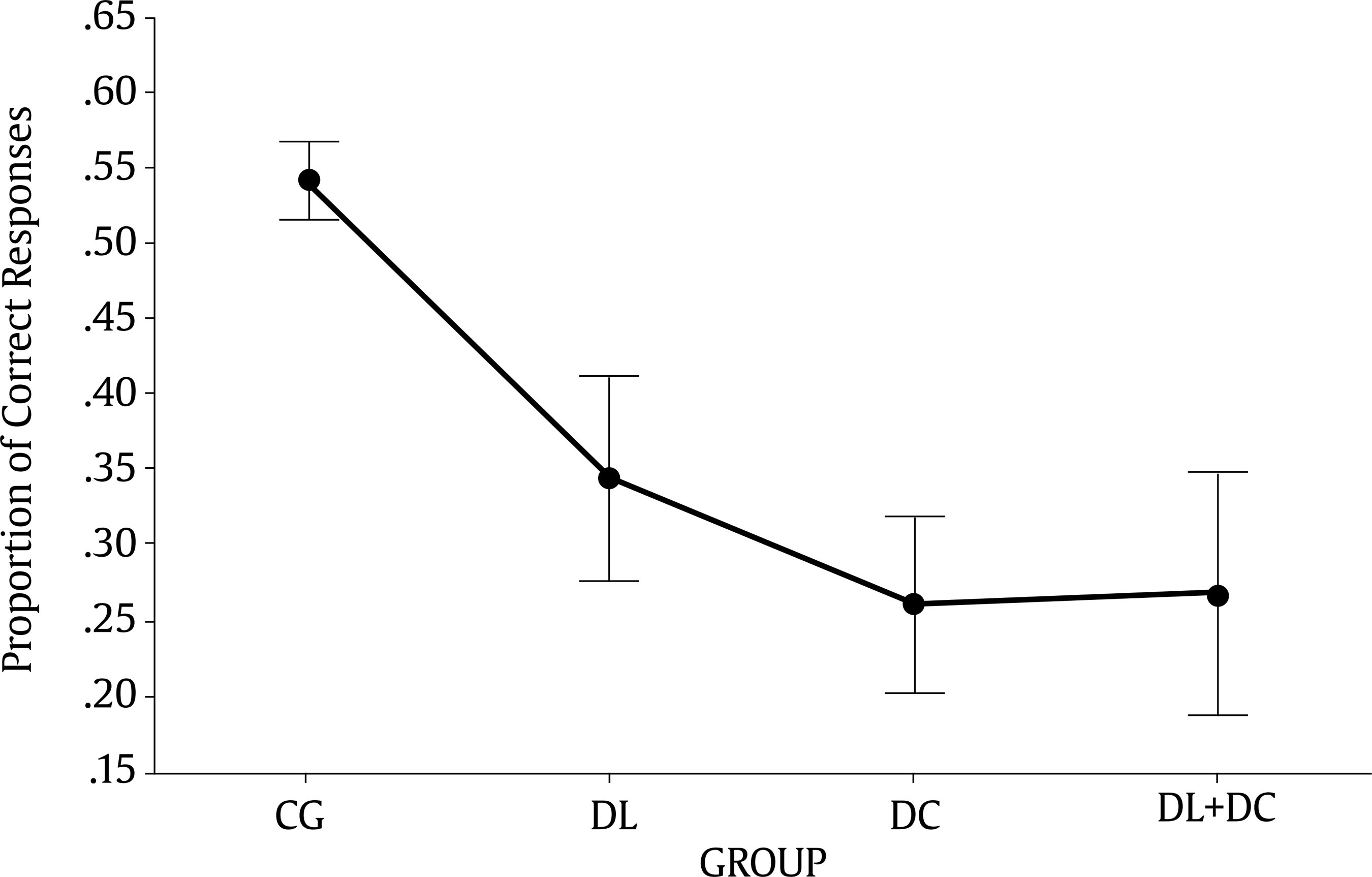

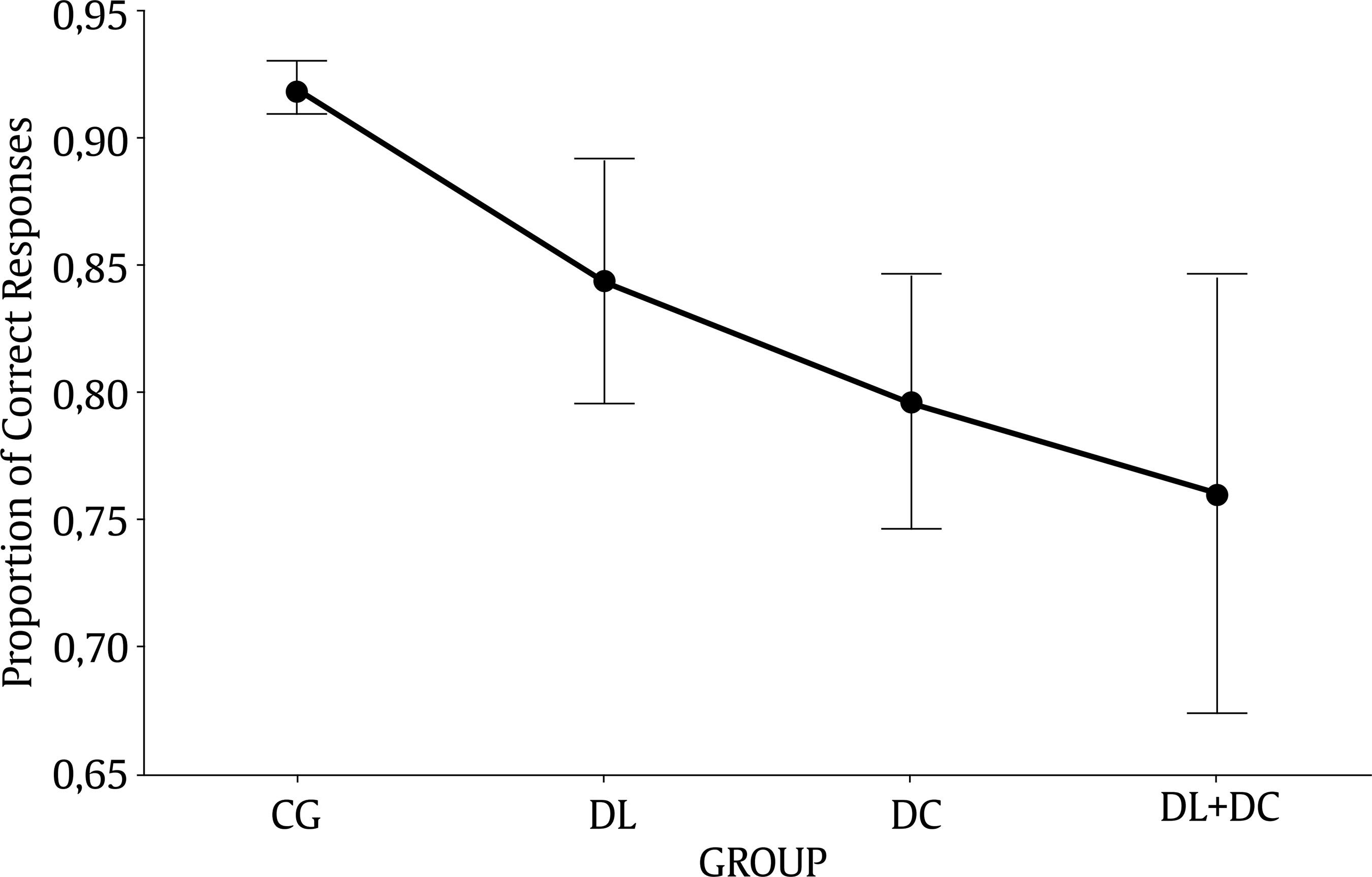

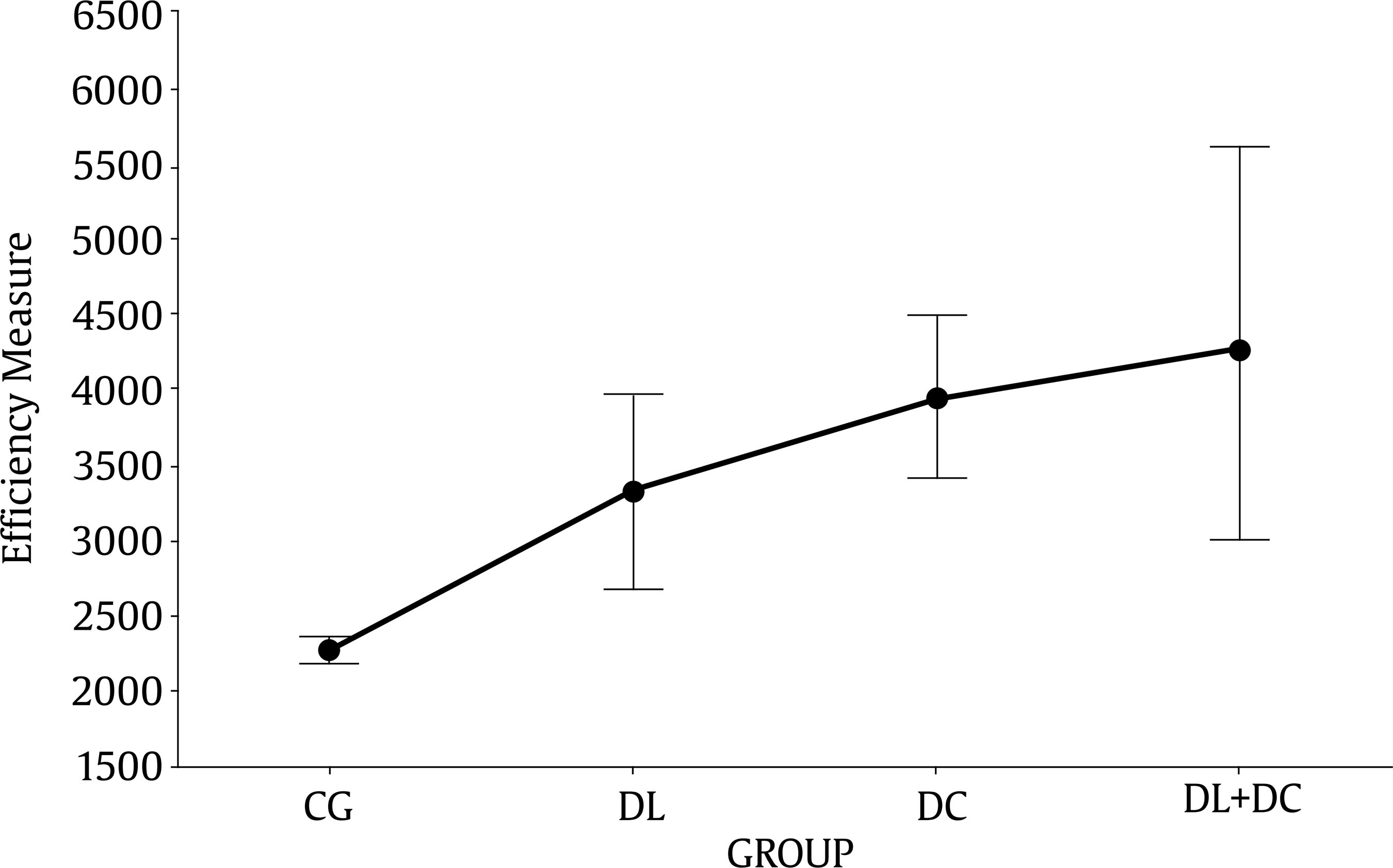

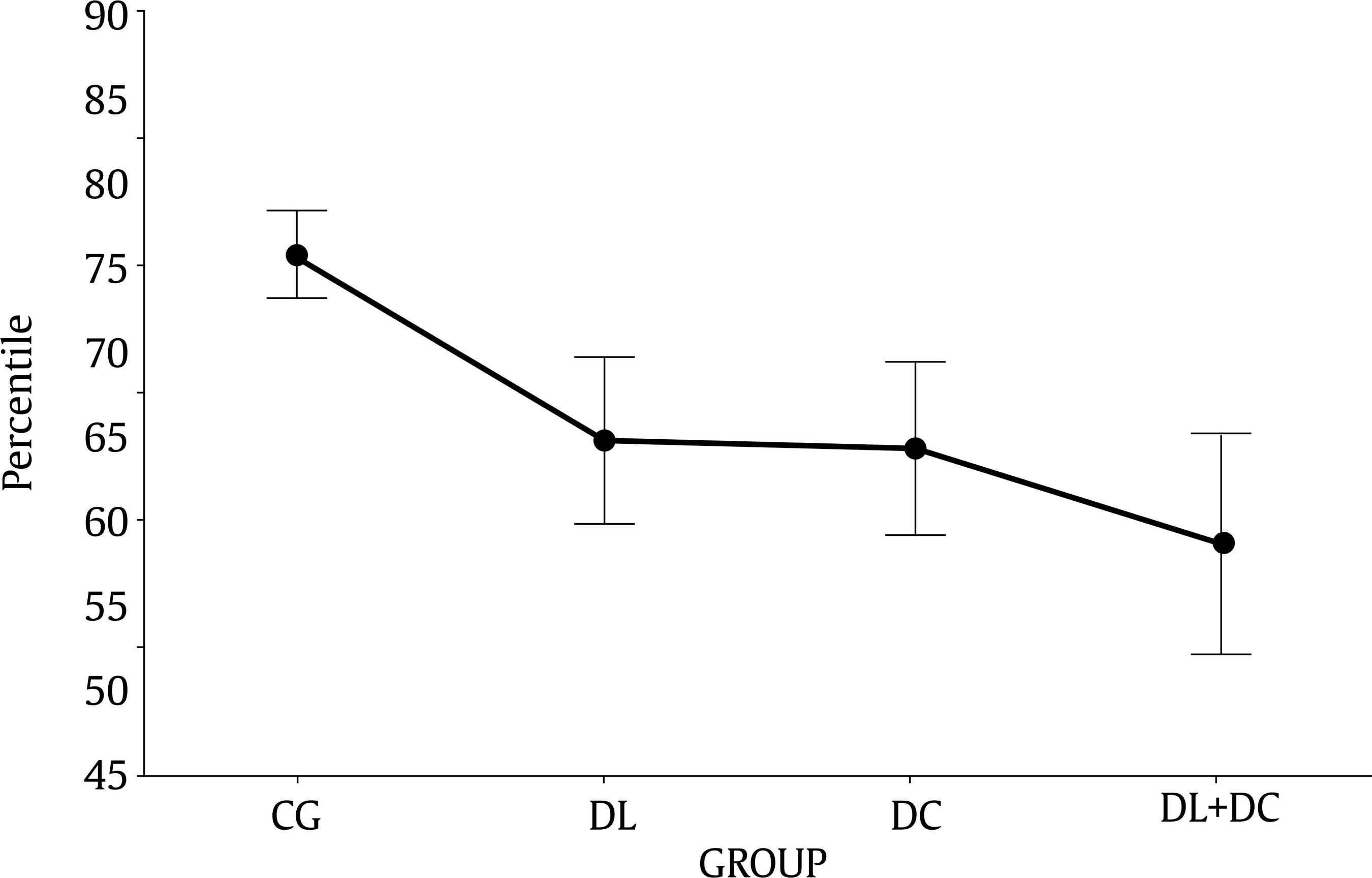

Correspondence: danilkacc@gmail.com (D. Castro Cañizares).According to the fifth revised edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2022), specific learning disabilities (SLD) are characterized by problems with academic skills such as reading, writing, or mathematics that interfere with the development of more advanced academic learning. A distinctive feature of SLD is that they often occur in comorbidity with each other. For example, comorbidity between dyslexia and dyscalculia has been reported to range from 10% to 70%, depending on the assessment criteria and the characteristics of the sample assessed (Landerl et al., 2013; Peters et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2015). Recent cognitive theories and neuropsychological evidence have considered different types of models to explain the origin of SLD. These models are based on basic cognitive abilities that have been supported by several studies as predictors of learning development (Castro et al., 2017; Castro et al., 2021; De Smedt & Gilmore, 2011; Hyde et al., 2014; Kolkman et al., 2013; LeFevre et al., 2010; Nevo & Breznitz, 2011; Reigosa et al., 2013). These basic cognitive skills may be domain-specific (e.g., basic numerical skills) or domain-general (e.g., executive functions). For the purposes of this research, we will focus on models that explain that learning difficulties, both dyslexia (Bogaerts et al., 2014; Marks et al., 2024) and dyscalculia (Agostini et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023; Luoni et al., 2023; Mishra & Khan, 2023), are linked to impairments in general cognitive abilities, including automaticity, attention, and executive functions (EFs) (Agostini et al., 2022; Carriedo et al., 2024; Lonergan et al., 2019; Mingozzi et al., 2024; Smith-Spark & Gordon, 2022; Ten Braak et al., 2022). Multiple previous studies have shown that EFs play an important role in children’s academic development and predict mathematical and reading ability. They have also been found to moderate the relationship between early academic skills and subsequent learning (Cameron et al., 2019; Carriedo et al., 2024; Mishra & Khan, 2023; Peng et al., 2018; Spiegel et al., 2021; Ten Braak et al., 2022). The term EFs encompasses top-down processes that enable attentional control and adaptive behavior (Zelazo & Carlson, 2020). Critical core subcomponents within this group of processes have been described, such as inhibition, updating information in working memory (WM), and cognitive flexibility (Miyake et al., 2000). Furthermore, other authors, such as Diamond (2013) and Ibbotson (2023), have proposed that higher-order EFs, such as reasoning and fluid intelligence, are built on the foundations of these basic subcomponents. These self-regulatory skills enable individuals to retain and process relevant information, control impulsive responses, and adapt to new cognitive demands. It has been suggested that difficulties in executive functioning can interfere with the development of academic skills due to the high level of attentional control required for these processes and result in learning difficulties in reading and mathematics (Bazen et al., 2020; Lonergan et al., 2019; López-Zamora et al., 2025; Marks et al., 2024; Nouwens et al., 2021). For reading, WM is essential for maintaining the sequence of sounds or words while decoding and for integrating the information read with prior knowledge during comprehension. Inhibition enables the suppression of incorrect responses or interference; for instance, it helps us to avoid confusing similar words or correct errors when reading aloud. Cognitive flexibility enables us to switch strategies when a text is complex or requires different levels of inference. In mathematics, working memory enables us to retain the relevant information of a problem, perform mental calculations and follow multi-step instructions. Inhibition is necessary to avoid applying inappropriate automatic procedures (e.g., adding instead of subtracting), while flexibility enables us to switch between different problem-solving strategies and adapt to new types of exercises or correct errors in the process. At a higher level of integration, fluid intelligence is important in both reading comprehension (e.g., inferring non-explicit meanings or structures) and mathematical problem solving (e.g., identifying patterns, establishing logical relationships, and adapting strategies to new tasks). Transdiagnostic research has identified differences in EFs as a common factor in SLD (e.g., Sadozai et al., 2024; Willcutt et al., 2013). Some research has shown that the development of EFs in early childhood can accurately predict a child’s academic progress in kindergarten and help identify those at risk of experiencing learning difficulties at school (Kalstabakken et al., 2021). It has even been suggested that EF skills are better at predicting growth in mathematical ability than mathematical instruction (Ribner, 2020). WM is the executive function most found to be impaired in SLD, both verbal and visuospatial (Castro et al., 2017; He et al., 2025; López-Resa & Moraleda-Sepúlveda, 2023; Peng & Fuchs, 2016; Wilson et al., 2015). Poor verbal or phonological short-term memory are common in reading disabilities and play a role in early math skill (Viesel-Nordmeyer et al., 2022). It has been suggested that WM difficulties can account for 30-70% of cases of comorbidity between math and reading disabilities in individuals diagnosed with SLD (Willcutt et al., 2013). Furthermore, WM difficulties can be useful in distinguishing between children with reading disabilities but no math disabilities, and those with co-occurring math disabilities. In addition, comorbidity between reading and math disabilities has been associated with behavioral difficulties in working memory and reduced visual cortex activation during a visuospatial working memory task (Marks et al., 2024). Students with mathematical disabilities have been found to have difficulties in updating numbers in verbal WM, which affects their performance in mental arithmetic and numeracy (Pelegrina et al., 2015). Several cross-sectional studies assessing visuospatial WM have found significant differences between groups of students with and without mathematical disabilities (Kroesbergen & van Dijk, 2015; Kuhn et al., 2016). In the case of students with dyslexia, difficulties have been found in the phonological representations that are temporarily stored in the WM (Artuso et al., 2021; Dobó et al., 2022; Lonergan et al., 2019; Nouwens et al., 2021), so these students may have difficulty in reviewing or updating this information during the short-term retention period and may be more prone to losing the information they are reading (Pelegrina et al., 2015). In this regard, it has been reported that scores on WM tasks predict performance on reading tasks, even when controlling participants’ specific phonological abilities (Nevo & Breznitz, 2011). It has also been found that updating in WM plays a dominant role for reading comprehension development (Meixner et al., 2019). A recent study found that children with dyslexia have a verbal working memory deficit, whereas children with dyscalculia have deficits in both verbal and visual-spatial working memory. Children with both dyslexia and dyscalculia generally exhibit a profile characterised by the summation of the deficits of the two disorders (Mingozzi et al., 2024). Another EF that has often been linked to learning is inhibitory control. Recent meta-analyses have examined the relationship between inhibitory control and mathematical ability (for reviews, see Emslander & Scherer, 2022; Spiegel et al., 2021). These studies suggest that there is a stronger correlation between inhibitory control and more complex mathematical ability, such as logical reasoning, than between inhibitory control and basic arithmetical skills. It has been described that better performance in mathematics and reading in preschool and first grade children is associated with better inhibitory skills (Blair & Razza, 2007; Espy et al., 2004; Visier-Alfonso et al., 2020). Inhibitory control has also been linked to learning difficulties in mathematics, particularly in arithmetic (D’Amico & Passolunghi, 2009; Geary, 2013; Willcutt et al. 2013). On the other hand, some studies have reported that children with mathematical disabilities show a general impairment in tasks that assess inhibition of automatic responses or interference control (as in the classic Stroop task and its numerical variants, e.g., 2 4) and also in attentional control (as required in dual tasks, regardless of the numerical nature of the stimuli) (Peng et al., 2012). However, two studies using the Go/No-Go paradigm found no inhibition difficulties in children with mathematical difficulties compared to the control group (Censabella & Noël, 2007; De Weerdt et al., 2013). Deficits in response inhibition have also been linked to reading disabilities. Poorer performance on executive function tasks, particularly inhibitory control and planning, has been reported in children with reading difficulties (Moreno et al., 2019). Previous studies have found that children with dyslexia have lower inhibitory control scores than their control peers (Horowitz-Kraus, 2012; Levinson et al., 2018). Similarly, in a study by Barbosa et al. (2019), where children with dyslexia were tested using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), a higher percentage of perseverative errors were recorded in children with dyslexia, suggesting that shifting and inhibition abilities may be compromised in these patients. Likewise, in the study by Miranda et al. (2012), in which performance in inhibitory control and sustained attention was assessed using the Continuous Performance Test (CPT) in schoolchildren with dyslexia, the authors found difficulties in both inhibitory control (impulsivity) and sustained attention. However, in a more recent study (Barbosa et al., 2019), where the performance of 8-13-year-old schoolchildren with dyslexia was assessed against a control group also using the CPT, the results showed that schoolchildren with dyslexia had a slow motor response and a tendency to make omission errors, while no difficulties were found in the inhibition of impulsive responses. Cognitive flexibility is another EF that predicts academic achievement in both reading and mathematics (Lonergan et al., 2019; Magalhães et al., 2020; Morgan et al., 2018; Yeniad et al., 2013). The meta-analysis by Yeniad et al. (2013) showed that cognitive flexibility predicts the development of mathematical and reading skills in children aged 4-13 years. A more recent study found that differences in cognitive flexibility, as measured by the shifting task and the non-symbolic magnitude comparison task, could distinguish between children with dyscalculia and those with typical numerical processing skills (Li et al., 2023). Regarding SLD, in general, children with difficulties in mathematics have shown impairments in tasks that assess cognitive flexibility (McDonald & Berg, 2018; Willcutt et al., 2013). Children with difficulties in mathematics have more difficulty in shifting their attentional focus between multiple responses depending on the demands of the context, which could lead to difficulties in solving problems that require the completion of several consecutive steps or switching between different procedures, as in the case of multiplication and division (Li et al., 2023; McDonald & Berg, 2018; Willcutt et al., 2013). In relation to reading disabilities, previous studies found that children with dyslexia showed significant deficits in cognitive flexibility compared to controls, even after controlling differences in general intellectual ability (Barbosa et al., 2019; Moura et al., 2014). On the other hand, fluid intelligence (FI) has been established as a predictor of maths and reading learning (Green et al., 2017; Lin & Powell, 2021; Peng et al., 2019). In a sample of primary school children, Magalhães et al. (2020) found FI to be a good predictor of achievement in reading and mathematics. Given that FI is related to the ability to make inferences, predictions and connections in a story, its deficits can lead to difficulties in identifying the main idea of a text, which is why FI is thought to play a role in reading comprehension from infancy to adulthood (Grant & Prince, 2017). Children with dyslexia appear to experience difficulties with fluid intelligence due to the additional cognitive load they encounter when processing written language (López-Zamora et al., 2025). This limits their ability to allocate sufficient cognitive resources to tasks requiring logic and abstract reasoning (Giazitzidou & Padeliadu, 2022). In general, few studies have examined the extent to which FI contributes uniquely (separately from general intelligence and other general cognitive skills) to the development of mathematical and reading competence in childhood (Green et al., 2017). Although deficits in FI do not account for all the variability in difficulties experienced by children with SLD, these specific deficits appear to contribute to the observed discrepancies between cognitive skills and academic achievement (Evans, 2019). Regarding the relationship between FI and mathematical disabilities, a study by Fuchs et al. (2010) analyzed the effect of basic numerical cognition and FI (assessed at the beginning of the first school year) on the development of mathematical problem solving throughout the school year. The authors found that FI had the same predictive ability as basic numerical cognition for children’s performance in verbal problem solving. Another study by Primi et al. (2010), which assessed students from second to eighth grade over two years, found that students’ initial level of fluent reasoning was positively correlated with the development of quantitative skills over the following two school years. More recently, Vasilyeva et al. (2025) found an interaction between basic EFs and fluid intelligence when predicting mathematics learning outcomes. The control component of EF (a composite of inhibition and cognitive flexibility) and the verbal WM component both showed a compensatory relationship with fluid intelligence. The positive impact of EF skills on mathematics learning was particularly pronounced at lower levels of fluid intelligence, demonstrating the influence of interactions between subcomponents on academic skill development. Despite the wealth of literature exploring EFs separately in dyslexia and dyscalculia, very few studies have included both types of SLD. As a result, the evidence for differences in executive functioning between children with reading and mathematics disabilities is mainly based on different studies rather than a direct comparison of these groups. Below are some studies that have compared groups with different SLD. A recent study (Capodieci et al., 2023) attempted to provide a comprehensive profile of EFs in primary school children with neurodevelopmental disorders (dyslexia, dyscalculia, and others). The results showed impairments in all components of the EFs assessed in these students. However, the authors did not analyze the functioning of these groups separately, but only as a whole (all disorders included in the study vs. control group). This was justified by the fact that a previous study (Brandenburg et al., 2015) found no significant differences in EFs between the different types of SLD. Similar results are shown in the study by Pestun et al. (2019). Similarly, Landerl et al. (2009) sought to identify possible differences in measures of auditory WM (digit and pseudoword repetition) and visuospatial WM (Corsi Cubes) but the authors found no intergroup differences. In contradiction to the above, in Swanson and Jerman’s (2006) study, children with mathematics difficulties performed better than those with comorbid difficulties (in reading) on verbal WM and visuospatial problem-solving tasks. In addition, they also performed better than children with reading difficulties on visuospatial WM tasks. On the other hand, Wang et al (2012) compared the inhibitory control performance of children with different types of SLD and found statistically significant differences between them on tasks involving both numerical and verbal stimuli. Subjects with dyscalculia performed worse on tasks involving numerical stimuli, and subjects with dyslexia performed worse on verbal tasks. The Present Study As described above, there is empirical evidence to support the hypothesis that SLDs, both dyslexia and dyscalculia, are associated with difficulties in executive functioning. However, very few studies have aimed to compare performance on executive function tasks between children with dyslexia, dyscalculia, and those with a comorbidity of both disorders. This type of comparison would allow us to determine whether impairments in executive functioning are similar in dyslexia and dyscalculia or whether, on the contrary, there are some EFs that are more impaired in one or the other SLD. This comparison would also allow us to determine whether the changes are more severe in those individuals who have comorbidity of both SLDs. Another element to point out about previous studies is that they usually focus on the assessment of isolated EFs, rather than a more comprehensive assessment that includes multiple executive functions. Bearing these points in mind, the general aim of this study is to compare executive functioning (working memory, inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility and fluid intelligence) in primary school children diagnosed with dyslexia, dyscalculia, and with a comorbidity of both disorders, with school children without learning disabilities. We expect that if there is a different executive functioning profile in each type of learning disability (dyslexia, dyscalculia, and comorbidity of both) the impairments in executive functions will be significantly different between these groups. However, if executive difficulties are similar, regardless of the type of learning disability, a similar executive functioning profile is expected in all groups with SLD, but with worse performance in the group with comorbidity, due to the sum effect of both disorders. Participants A non-probabilistic convenience sample was used to select participants in 31 primary schools in the city of Santiago de Chile. The sample consisted of a total of 289 students from second to sixth grade: 175 participants made up the group of students without learning difficulties or control group (CG), 50 participants were part of the group of students with a diagnosis of dyslexia (DL), 45 participants made up the group of students with a diagnosis of dyscalculia (DC), and 19 participants took part of the group of students with a diagnosis of comorbidity between dyslexia and dyscalculia (DL+DC). The control group included students who, according to a checklist completed by the class teacher of each participant, were not at risk of SLD. The groups with learning difficulties included students with a previous diagnosis of DL, DC, or DL+DC. The diagnosis of dyslexia and dyscalculia was carried out in accordance with the current regulations of the Chilean Ministry of Education within the framework of the School Integration Programme (MINEDUC, 2013). This programme outlines the processes and professionals responsible for diagnosing SLD. The EVALÚA 4.0 Psychopedagogical Battery (García & González, 2019) was used for the diagnosis. This is a standardized and validated tool in Chile. According to the criteria of this battery, a dyslexia diagnosis is based on the standardized score obtained in the General Reading Index (IGL), which comprises the reading comprehension and reading accuracy subtests. Dyscalculia is diagnosed using the General Mathematics Index (IGM), which consists of numerical calculation and problem-solving subtests. Additionally, the General Cognitive Ability Index (IGC) is calculated to determine whether performance in reading or mathematics significantly deviates from the student’s overall cognitive ability. The IGC includes perceptual organization, series, memory, attention, and classification subtests. A discrepancy score is obtained by subtracting the IGL or IGM from the standardized IGC score, which allows the gap between cognitive and academic skills to be evaluated. Dyslexia is diagnosed when the IGL is more than two standard deviations (SDs) below the mean, and the discrepancy between the IGC and the IGL is less than 1.5 SDs. Similarly, dyscalculia is diagnosed when the IGM is more than 2 SDs below the mean and the discrepancy between the IGC and IGM is less than 1.5 SDs. If a student scores more than two SDs below the mean in both the IGL and IGM, they are given a comorbid dyslexia and dyscalculia diagnosis (DL+DC). Materials Visuospatial Working Memory Tasks To evaluate children from fourth to sixth grade, the task proposed by Castro et al. (2017) was used, which consists of the presentation of a grid of white squares that change color from white to red, forming a sequence. Once the presentation of the sequence is finished, the child should point to the sequence of red squares observed, but in reverse order (from the last red square presented to the first square of the sequence). In order to achieve an appropriate level of complexity, the sequences presented increase in number of elements as the grade level increases. A reliability coefficient of a = .75 has been previously reported for this task (Castro et al., 2021). To assess second and third graders, a version of this task was used in which the grid was modified by fish tanks with a fish moving through the tanks. The procedure is the same, but the stimuli has been changed to increase the motivation of younger children. Each task is preceded by four practice trials. One point is awarded for each correct sequence in the task and all the points obtained are added up. Inhibitory Control Task This task was developed by Castro et al. (2024) using the Go/No-Go paradigm. The authors report a reliability coefficient of a = .75 for the task. The task consists of two blocks of 40 stimuli each. In each block, 25% of the stimuli are No-Go items. There are six practice items at the beginning of each block. The stimuli are coloured geometric figures with a happy or sad expression. In the first block the participant must press the space bar (as quickly as possible) when a figure with a happy expression appears on the screen and does nothing when a figure with a sad expression appears on the screen. In the second block, the participant must press the space bar when a figure with a sad expression appears on the screen and do nothing when a figure with a happy expression appears on the screen. One point is awarded for each non-response to the No-Go stimuli in the task, and all the points obtained are added up. Cognitive Flexibility Tasks Two tasks were designed based on the level of difficulty for the different school years: a version of the test developed by Mueller and Esposito (2014) was used to assess second and third graders. The task consists of 24 items administered in a single stimulus block, preceded by six practice items. It consists of the presentation of a geometric figure (square or rhombus) in the centre of the screen. This figure may appear in two colours (red or blue). At the bottom of the screen, a smaller rhombus and a square appear (one on the right and one on the left at random), which can be coloured red or blue at random too. The participant must select (as quickly as possible, avoiding making mistakes) the small figure that is in the same shape as the figure in the centre of the screen, regardless of its colour. If the figure on the left is chosen, the participant must press the (z) key to answer. If the figure on the right is chosen, the participant must press the (-) key to answer. A reliability coefficient of a = .92 has been reported for this task (Castro et al., 2024). The task proposed by Castro et al. (2022), which consists of 26 items presented in a single block of stimuli preceded by six practice items, was used to assess schoolchildren from fourth to sixth grade. It consists of the presentation of two squares separated by a fixation point (red asterisk). On the left square is the question “Is the woman happy?” and on the right square is the question “Does the man wear glasses?”. In each trial, an image showing two human figures (a man and a woman) was randomly displayed in one of these white squares (to the right or the left of the fixation point). Across all trials, two features were varied and randomized between the two human figures: glasses (both with glasses, both without glasses, or only one figure with glasses) and facial expression (both happy, both sad, or one happy figure and one sad figure). The participants have to answer (as quickly as possible, avoiding mistakes) the question corresponding to the side on which the picture appears (e.g., if the picture appears on the left, the subject has to answer the question “Is the woman happy?”). If the answer is “YES”, the participant must press the (z) key to answer. If the answer is “NO”, the participant must press the (-) key to respond. For this task, previous studies have reported a reliability coefficient of a = .78 (Mazuera-Velásquez et al., 2025). In both tasks, one point is awarded for each correct response, and all the points obtained are added up. In addition, the reaction time (RT) is recorded for each correct answer. Raven’s Coloured Matrices (RCM) Test to Assess Fluid Intelligence The RCM Test (Raven, 1993) assesses the ability to solve problems in novel situations, without the influence of language skills or cultural background. It consists of 36 items presented in three blocks (A, AB, and B). Participants must establish a logical sequence between a figure missing a segment and six possible answers. From these, they must choose the correct figure that completes the missing segment. One point is awarded for each correct answer, giving a total of 36 possible points. A percentile value is calculated from the score obtained, considering the age of the participant. For this test, previous studies have reported a reliability coefficient of a = .82 (Castro et al., 2021). Procedure Following the ethical requirements for research with human beings, written consent from all participant’s parents were obtained, and all participants provided written assent for assessments. The assessments were conducted in a quiet room within the school in two sessions of approximately 30 minutes each. In the first session the Raven’s Coloured Matrices Test was administered and in the second session the remaining executive function tasks were administered. Statistical Analysis First, descriptive analyses of the sample and the performance of each group in each of the executive functions assessed were carried out, using measures of frequency, central tendency, and dispersion. Considering that this study includes students from different primary school years (from second to sixth grade) and that the tasks have different numbers of items for the different school years, instead of using the total score in the visuospatial working memory, inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility tasks, we used the proportion of correct answers (PC) obtained in the task, thus achieving a homogenization of the data. The proportion of correct responses (PC) was calculated by dividing the total number of points scored by the subject (PS) by the total number of items in the task (TP): PC = PS/TP. To obtain the participant’s performance on the cognitive flexibility tasks, an efficiency measure (EM) was calculated using the following formula: EM = RT * (1 + 2 * PE). PE is the proportion of errors which is calculated as: 1 – proportion of correct responses (PC). EM is an inverse measure. This means that a higher value of EM indicates poorer performance on the task. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check that the results obtained met the normality assumption, and Levene’s test was used to assess homoscedasticity. Given that the results obtained did not meet the assumption of normality (p < .10 for all the variables studied) and that, in general, the variances among the groups were not homogeneous, non-parametric analyses were carried out. In accordance with the above, one-factor ANOVAs (Kruskal-Wallis) for multiple independent samples were run, to compare the performance of the study groups on the different executive functions assessed. In addition, multiple comparisons of z-values were performed to identify specific differences among the groups tested. In each case where the ANOVA showed significant results, the eta-squared coefficient (η2) was calculated. This coefficient provides a measure of effect size. Sample Descriptive Analyses Table 1 shows the characteristics of the groups and the means and standard deviations of the results obtained by each group. Table 1 Description of the Sample and the Results Obtained by Each Group in the Executive Functions Assessed   Note. N = number of subjects in the group; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; CG = group without learning difficulties; DL = group diagnosed with dyslexia; DC = group diagnosed with dyscalculia; DL+DC = group diagnosed with comorbid dyslexia and dyscalculia; PC = proportion of correct responses. 1EM (efficiency measure) is an inverse measure; a higher value indicates lower performance. Between-group Comparisons of Performance on Executive Function Tasks Visuospatial Working Memory Task The results of the one-factor ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) show that there are statistically significant differences among groups (see Figure 1): χ2Kruskal-Wallis (3, 289) = 82.94, p < .001, η2 = .29, IC 95% [.23, 1.00], indicating a large effect size (Avello, 2020). Specific between-group comparisons indicate significant differences between the CG and the learning disability groups as follows: for the DL group: z = 5.47, p < .001; for the DC group: z = 7.26, p < .001; for the DL+DC group: z = 5.14, p < .001. No significant differences were found between the groups with SLD in this task. Figure 1 Group Means of Proportion of Correct Responses on the Visuospatial Working Memory Task.   Note. CG = group without learning difficulties; DL = group diagnosed with dyslexia; DC = group diagnosed with dyscalculia; DL+DC = group diagnosed with comorbid dyslexia and dyscalculia. Vertical bars denote .95 confidence intervals. Inhibitory Control Task The results of the one-factor ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) show that there are statistically significant differences among groups (see Figure 2): χ2Kruskal-Wallis (3, 289) = 39.89, p < .001, η2 = .14, IC 95% [.10, 1.00], indicating a large effect size. Specific between-group comparisons indicate significant differences between the CG and the learning disability groups as follows: for the DL group: z = 2.92, p < .05; for the DC group: z = 4.96, p < .001; for the DL+DC group: z = 4.09, p < .001. No significant differences were found between the groups with SLD in this task. Figure 2 Group Means of Proportion of Correct Responses on the Inhibitory Control Task.   Note. CG = group without learning difficulties; DL = group diagnosed with dyslexia; DC = group diagnosed with dyscalculia; DL+DC = group diagnosed with comorbid dyslexia and dyscalculia. Vertical bars denote .95 confidence intervals. Cognitive Flexibility Task The results of the one-factor ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) show that there are statistically significant differences among groups (see Figure 3): χ2Kruskal-Wallis (3, 289) = 57.13, p < .001, η2 = .20, IC 95% [.14, 1.00], indicating a large effect size. Specific between-group comparisons indicate significant differences between the CG and the learning disability groups as follows: for the DL group: z = 3.39, p < .01; for the DC group: z = 6.54, p < .001; for the DL+DC group: z = 4.31, p < .001. Among the SLD groups, significant differences were found only between the DL and the DC groups: z = 2.67, p < .05. Figure 3 Group Means of the Efficiency Measure in the Cognitive Flexibility Task.   Note. CG = group without learning difficulties; DL = group diagnosed with dyslexia; DC = group diagnosed with dyscalculia; DL+DC = group diagnosed with comorbid dyslexia and dyscalculia. Vertical bars denote .95 confidence intervals. Raven’s Coloured Matrices Test The results of the one-factor ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) show that there are statistically significant differences among groups (see Figure 4): χ2Kruskal-Wallis (3, 289) = 32.69, p < .001, η2 = .11, IC 95% [.07, 1.00], indicates medium to large effect size. Specific between-group comparisons indicate significant differences between the CG and the learning disability groups as follows: for the DL group: z = 3.56, p < .01; for the DC group: z = 3.58, p < .01; for the DL+DC group: z = 3.74, p < .01. No significant differences were found between the groups with SLD on this test. Figure 4 Group Means of Percentiles in the Rave’s Coloured Matrices Test.   Note. CG = group without learning difficulties; DL = group diagnosed with dyslexia; DC = group diagnosed with dyscalculia; DL+DC = group diagnosed with comorbid dyslexia and dyscalculia. Vertical bars denote .95 confidence intervals. The general aim of this study was to compare the executive functioning of primary school children diagnosed with dyslexia, with dyscalculia and with comorbidity of both disorders, compared to school children without learning disabilities. The results showed significant differences between the executive functioning of students diagnosed with SLD and students without learning disabilities. In all the executive functions assessed, the performance of the students diagnosed with SLD was significantly lower than that of the control group. These findings support the theoretical assumption that the difficulties experienced in SLD are associated with deficits in domain-general cognitive skills (Agostini et al., 2022; Bogaerts et al., 2014; Carriedo et al., 2024; Li et al., 2023; Lonergan et al., 2019; Luoni et al., 2023; Marks et al., 2024; Mingozzi et al., 2024; Mishra & Khan, 2023; Smith-Spark & Gordon, 2022; Ten Braak et al., 2022). Furthermore, the results are consistent with evidence from previous studies that have also found lower performance in school children with SLD on tasks involving visuospatial WM (Castro et al., 2017; He et al., 2025; López-Resa & Moraleda-Sepúlveda, 2023; Peng & Fuchs, 2016; Wilson et al., 2015), inhibitory control (Geary, 2013; He et al., 2025; Horowitz-Kraus, 2012; Moreno et al., 2019; Willcutt et al. 2013), cognitive flexibility (Chu et al., 2019; Colé et al., 2014; Horowitz-Kraus, 2012; McDonald & Berg, 2018; Moura et al., 2014), and in the assessments of the fluid intelligence (Evans, 2019; Fuchs, et al., 2010; Green et al., 2017; Primi et al., 2010; Shaywitz et al., 2002). The significant differences found between the executive functioning of students diagnosed with SLD and controls are also consistent with findings from previous studies examining the characteristics of brain connectivity networks in individuals with SLD. In the studies by Bathelt et al. (2018) and Estévez-Pérez et al. (2023), the authors note that the characteristic length of connectivity pathways is significantly longer in children with SLD, whereas in individuals without difficulties, information transfer is mediated by shorter pathways, suggesting a greater potential for integration of this information. This finding may indicate that compensatory mechanisms involving global reconfiguration of neural networks have been implemented in students with SLD, affecting not only specialized or modular circuits (numerical or phonological), but also the entire brain architecture. Specifically, these two studies found differences in parieto-frontal connectivity patterns, with more extensive and robust circuits in terms of anatomical connectivity probability in SLD subjects (higher number of frontal nodes – superior and medial). These results suggest the existence of compensatory strategies in SLD subjects that could involve EFs that depend on these frontal regions. The existence of these circuits could be an expression of inadaptive plasticity that appears in response to academic demands in the presence of alterations in specific circuits linked to numerical and/or reading processing. Therefore, these types of connections could be part of the etiology of difficulties in academic performance. In this regard, previous studies have also indicated that the optimal organization of brain networks depends on the presence of a small number of highly connected neuronal hubs (van den Heuvel et al., 2012). An optimal network architecture would support better learning ability as well as the optimal functioning of a particular set of cognitive skills, including EFs. For example, van den Heuvel et al (2009) found that shorter path lengths of neural networks in fronto-parietal regions were associated with higher scores on an intelligence scale. On the other hand, if we focus the analysis on comparing executive functioning between groups with different SLDs, we can point out that most previous studies on the relationship between EFs and SLDs have focused on analyzing only one type of SLD (either DL or DC) or have examined isolated EFs. Few previous studies have directly compared the executive functioning profiles of students with LD and CD and those with comorbidity between the two disorders. (e.g., Capodieci et al., 2023; Pestun et al., 2019; Swanson & Jerman, 2006; Wang et al., 2012). Accordingly, a relevant element of this study was to compare students with DL, DC and students with comorbidity of both SLDs, and also to assess four EFs between the groups: the three core EFs proposed in Miyake et al.’s (2000) models (WM, inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility) and fluid intelligence, which was proposed as a higher order EF in Diamond’s (2013) model, and whose development is closely linked to the integration of the core EFs (Ren et al., 2017). The comparative analysis between the groups with SLD showed a similar profile of executive functioning among the three groups (DL, DC, and DL+DC), although significant differences were found between the group diagnosed with DL and the group diagnosed with DC on the cognitive flexibility task. This finding is consistent with previous evidence showing impairments in cognitive flexibility, particularly in attentional shifting, in students with arithmetic difficulties (e.g. Castro et al., 2022; LeFevre et al., 2013; Valcan et al., 2020). It is of particular interest, and with little previous evidence, to know what happens to executive performance in cases of comorbidity between different types of SLD. In this study, although no significant differences were found between the groups with a diagnosis of SLD or CD and the group with SLD+CD, the latter group showed lower performance on all the EFs assessed (see Table 1). This trend may be an indicator that poorer executive functioning may influence the severity of learning difficulties in students with comorbid SLD. Limitations It should be noted that the DL+DC group in this study is much smaller than the other groups and tends to show greater dispersion in results. Therefore, results regarding comorbid cases should be interpreted with caution. Future studies should have a more balanced sample size across groups to enable more robust comparisons, improve statistical power, decrease variability and increase the reliability of differences observed between subgroups. Additionally, future studies should incorporate tasks that explore domain-specific skills (e.g., linguistic and numerical) to enable mediation and moderation analyses. These analyses would allow us to gain a deeper understanding of the variance in academic performance (in dyslexia, dyscalculia, and the comorbidity between both SLDs) that can be explained by EFs. Conclusions Overall, the results of this study indicate that students diagnosed with DL, DC, or DL+DC perform significantly worse than students without learning disabilities on the executive functions of visuospatial working memory, inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility and fluid intelligence. This finding supports the hypothesis of a connection between difficulties in EFs and the occurrence of SLD. Secondly, we found no differences in executive functioning between students with dyslexia and dyscalculia, only differences in cognitive flexibility, mainly in tasks related to switching between different stimuli. It is important to note that although in general no significant differences were found between the groups with SLD, the group with comorbidity of both disorders showed lower performance in all executive functions assessed, so that future studies should deepen this analysis. These results highlight the importance of assessing the different components of EFs as part of the identification and diagnosis of SLD, in addition to the assessment of domain-specific cognitive abilities (numerical or reading-related). Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Castro Cañizares, D., Mazuera Velázquez, T., & Estévez Pérez, N. (2026). Comparative study of executive functioning in schoolchildren with dyslexia, dyscalculia, and comorbidity of both disorders. Psicología Educativa, 32, Article e260447. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a4 Funding This study was funded by two grants from the National Agency for Research and Development (ANID), Chile: Basal Funds for Centers of Excellence FB0003/ Support 2024 AFB240004; and The Scientific and Technological Development Support Fund (FONDEF), Grant IT23I0003. References |

Cite this article as: Cañizares, D. C., Velázquez, T. M., & Pérez, N. E. (2026). Comparative Study of Executive Functioning in Schoolchildren with Dyslexia, Dyscalculia, and Comorbidity of Both Disorders. PsicologĂa Educativa, 32, Article e260447. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a4

Correspondence: danilkacc@gmail.com (D. Castro Cañizares).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS