Developmental Dynamics of Expectancy and Value Beliefs in STEM and Language: Gender Stereotyping Influences

[La dinámica del desarrollo de las creencias relativas a la expectativa y al valor de las asignaturas cientĂfico-tecnolĂłgicas y de lengua castellana: la influencia de los estereotipos de gĂ©nero]

Milagros Sáinz1 & Katja Upadyaya2

1Internet Interdisciplinary Institute, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC), Barcelona, Spain; 2Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies, University of Helsinki, Finland

https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a5

Received 16 March 2025, Accepted 25 August 2025

Abstract

Drawing on the Expectancy-Value Theory, the present study aims to analyze high school students’ developmental patterns of self-concept of ability, expectancies, intrinsic values, and utility values in various subject areas during the transition to post-compulsory secondary education (Baccalaureate) in Spain. A total of 1,805 secondary students (881 males, 924 females) participated the study. Most of the participants belonged to intermediate SES families. The results of the LGC analysis using a multiple group procedure show significant declines in all motivational dimensions and domains during the transition to Baccalaureate. Similarly, the initial level of each motivational dimension predicted its degree of development over the four-year period. The value components experienced further declines than the expectancies components. Gender differences were observed, with females showing more stability over time in the development of motivation in Spanish language. The theoretical and practical implications of these findings for future career-related choices are further discussed.

Resumen

Tomando como referencia la teoría de expectativa-valor, el presente estudio analiza patrones de desarrollo evolutivo del autoconcepto de habilidad, las expectativas, el valor intrínseco y la utilidad percibida en varias asignaturas cursadas por estudiantes de secundaria a lo largo de la transición a la educación secundaria post-obligatoria (Bachillerato) en España. Participaron en el estudio un total de 1,805 estudiantes (881 hombres y 924 mujeres), la mayoría pertenecientes a familias con nivel socioeconómico intermedio. Los resultados de los análisis mediante la curva de crecimiento latente con un procedimiento multi-grupo muestran una disminución significativa de todas las dimensiones motivacionales de las distintas materias durante la transición al Bachillerato. Igualmente, el nivel inicial de cada dimensión motivacional predice su grado de desarrollo a lo largo de los 4 años observados. Las dos dimensiones del componente valor experimentaron un mayor declive que las dimensiones del componente expectativa. Se han observado asimismo diferencias de género, siendo las chicas las que mayor estabilidad mostraron a lo largo del tiempo en el desarrollo de la motivación en lengua y literatura castellana. Se discuten las implicaciones teóricas y prácticas de estos resultados con respecto a la elección de carrera.

Palabras clave

Desarrollo, Expectativas, Valor intrĂnseco, Autoconcepto de habilidad, Utilidad percibidaKeywords

Development, Expectancies, Intrinsic value, Self-concept of ability, Utility valueCite this article as: Sáinz, M. & Upadyaya, K. (2026). Developmental Dynamics of Expectancy and Value Beliefs in STEM and Language: Gender Stereotyping Influences. PsicologĂa Educativa, 32, Article e260448. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a5

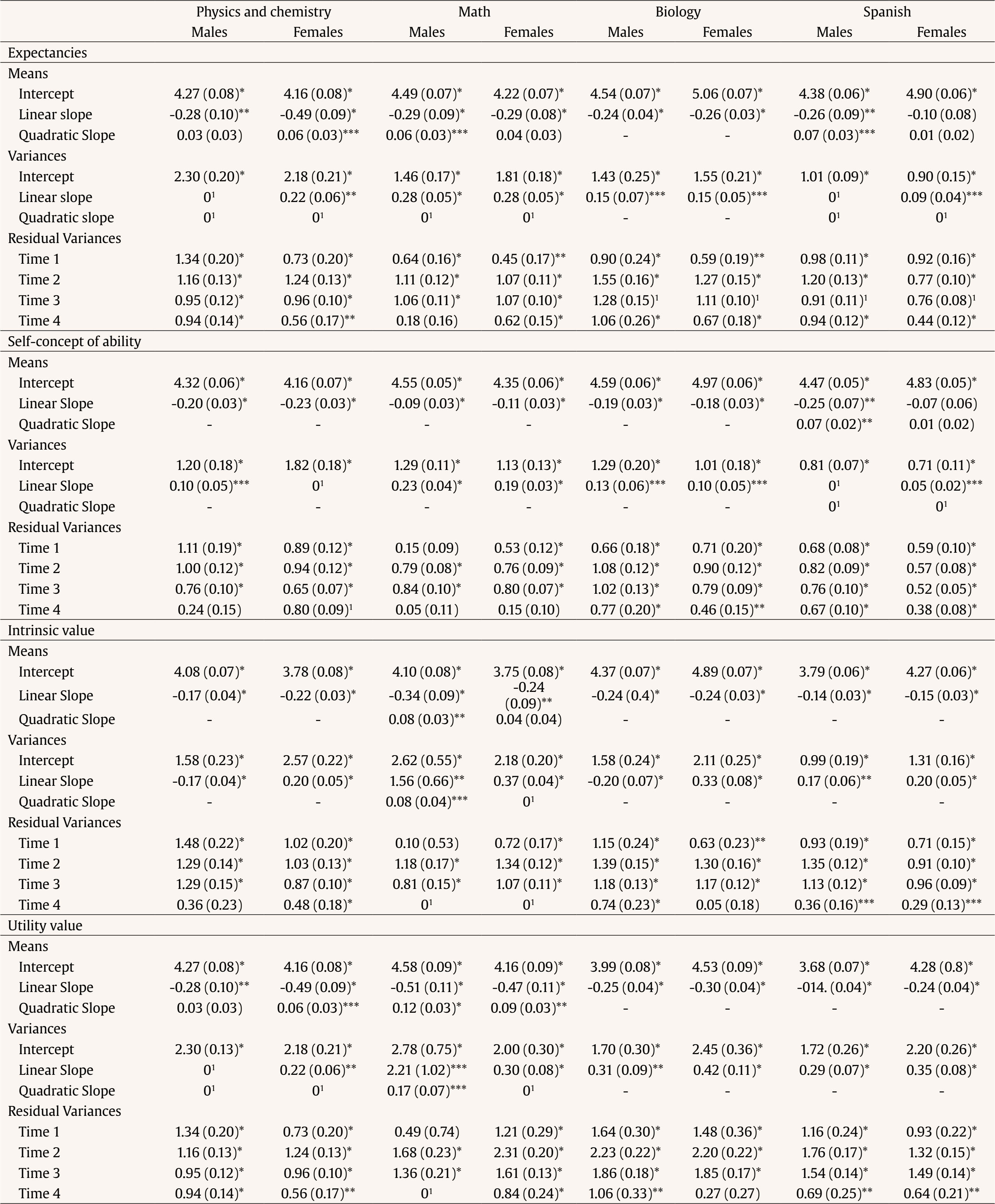

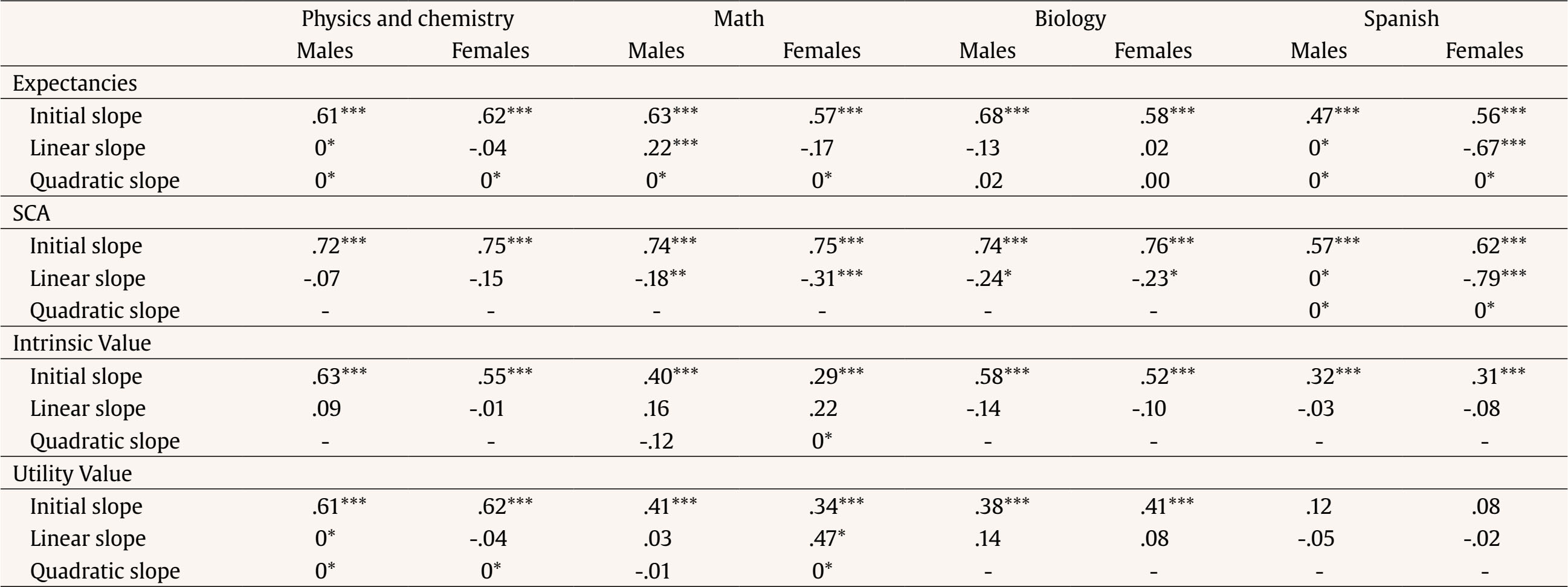

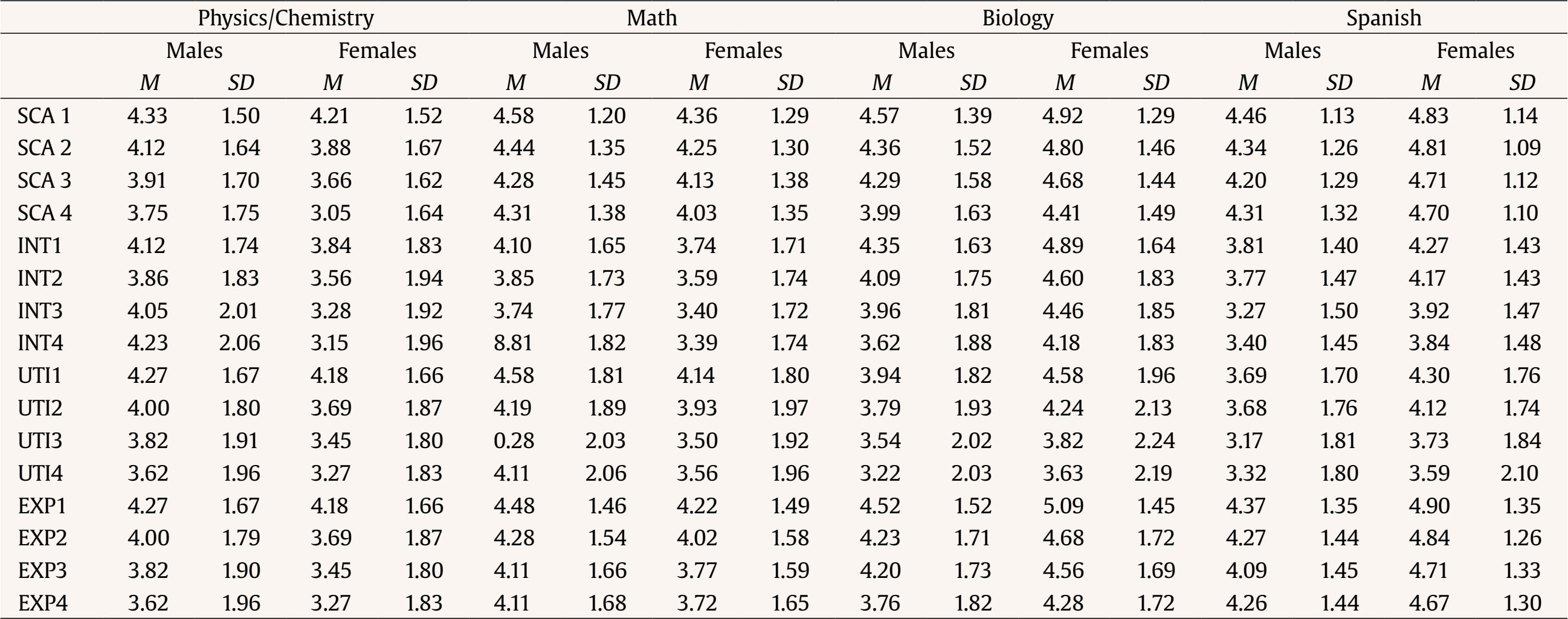

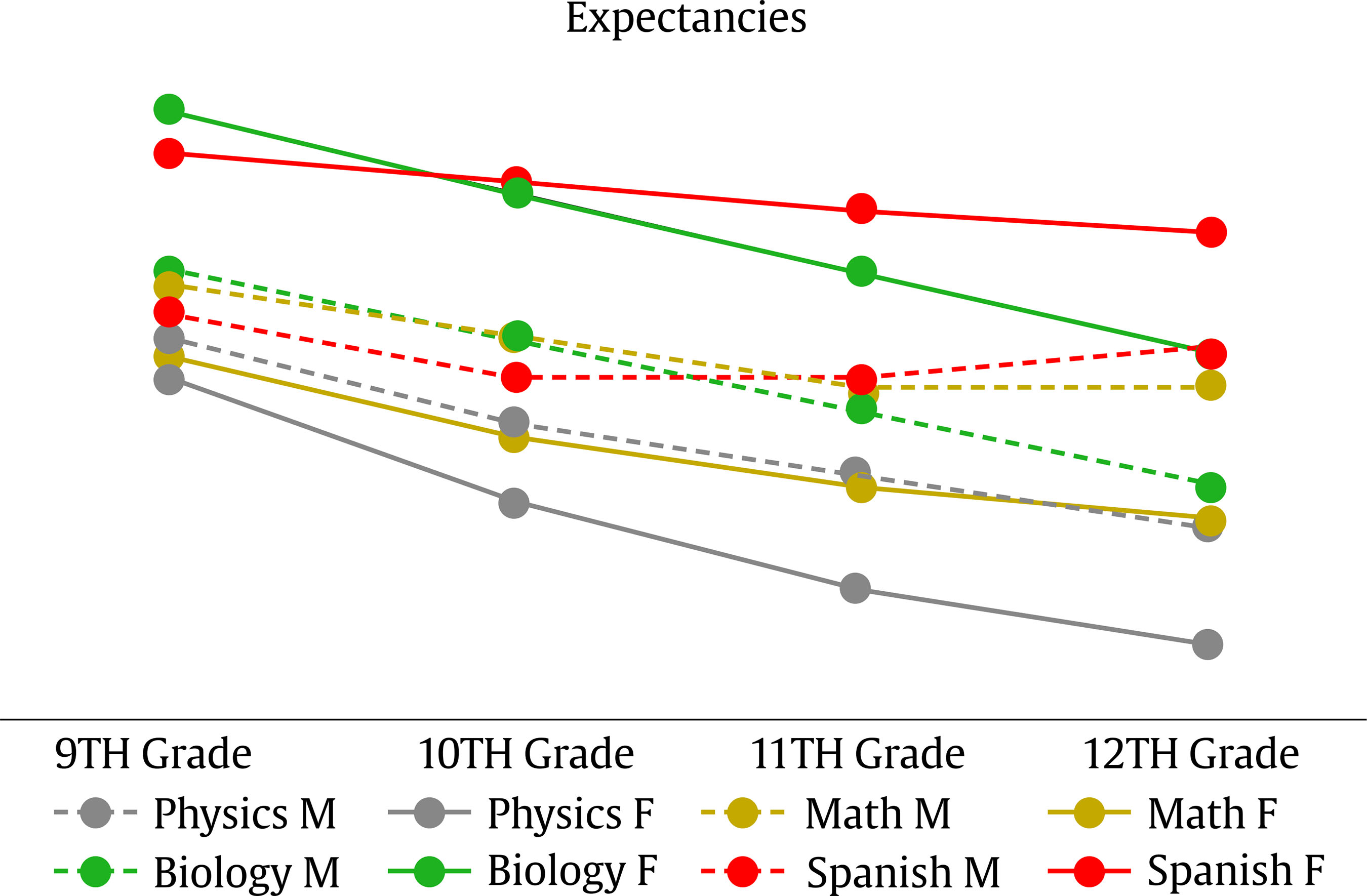

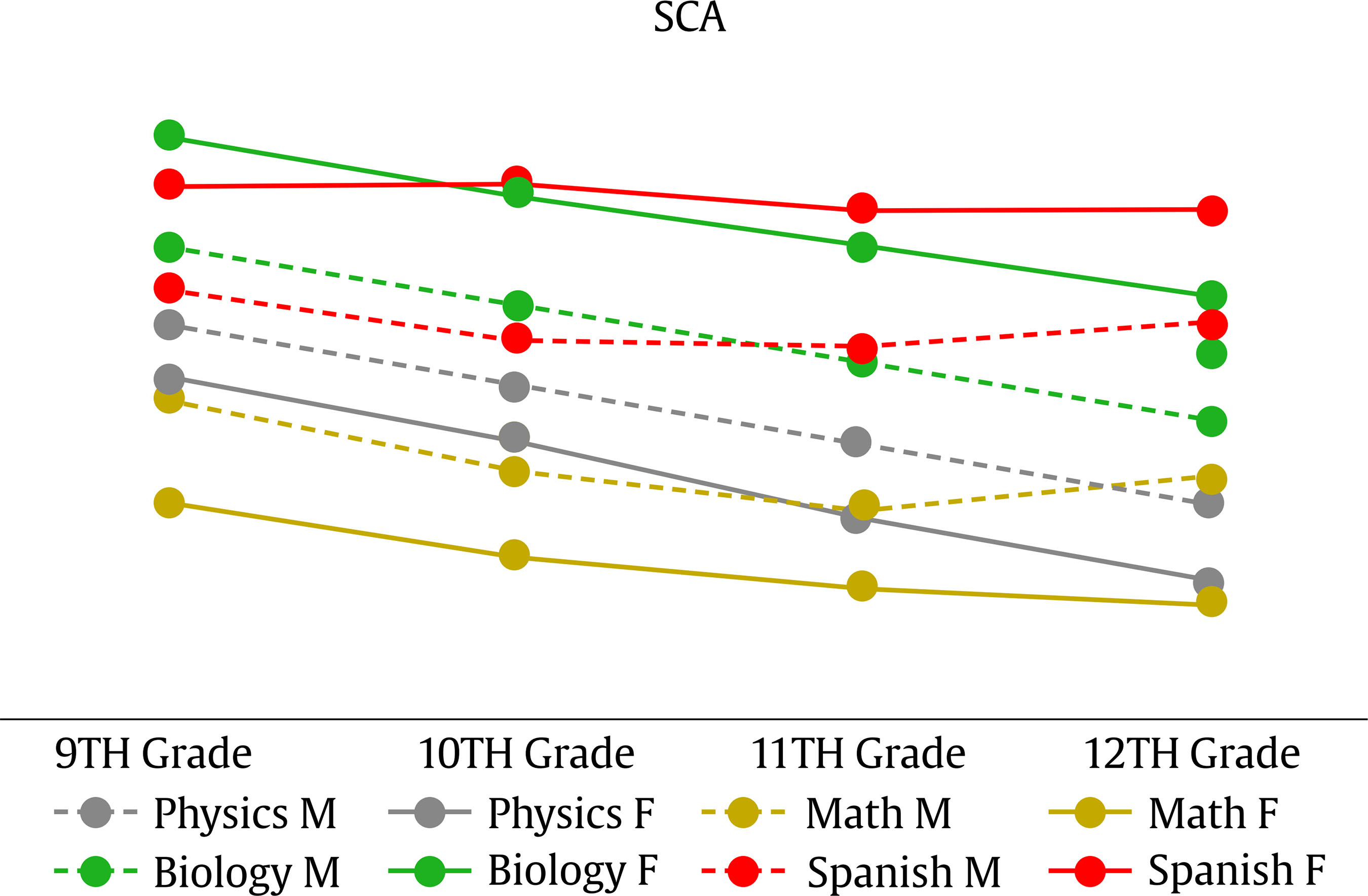

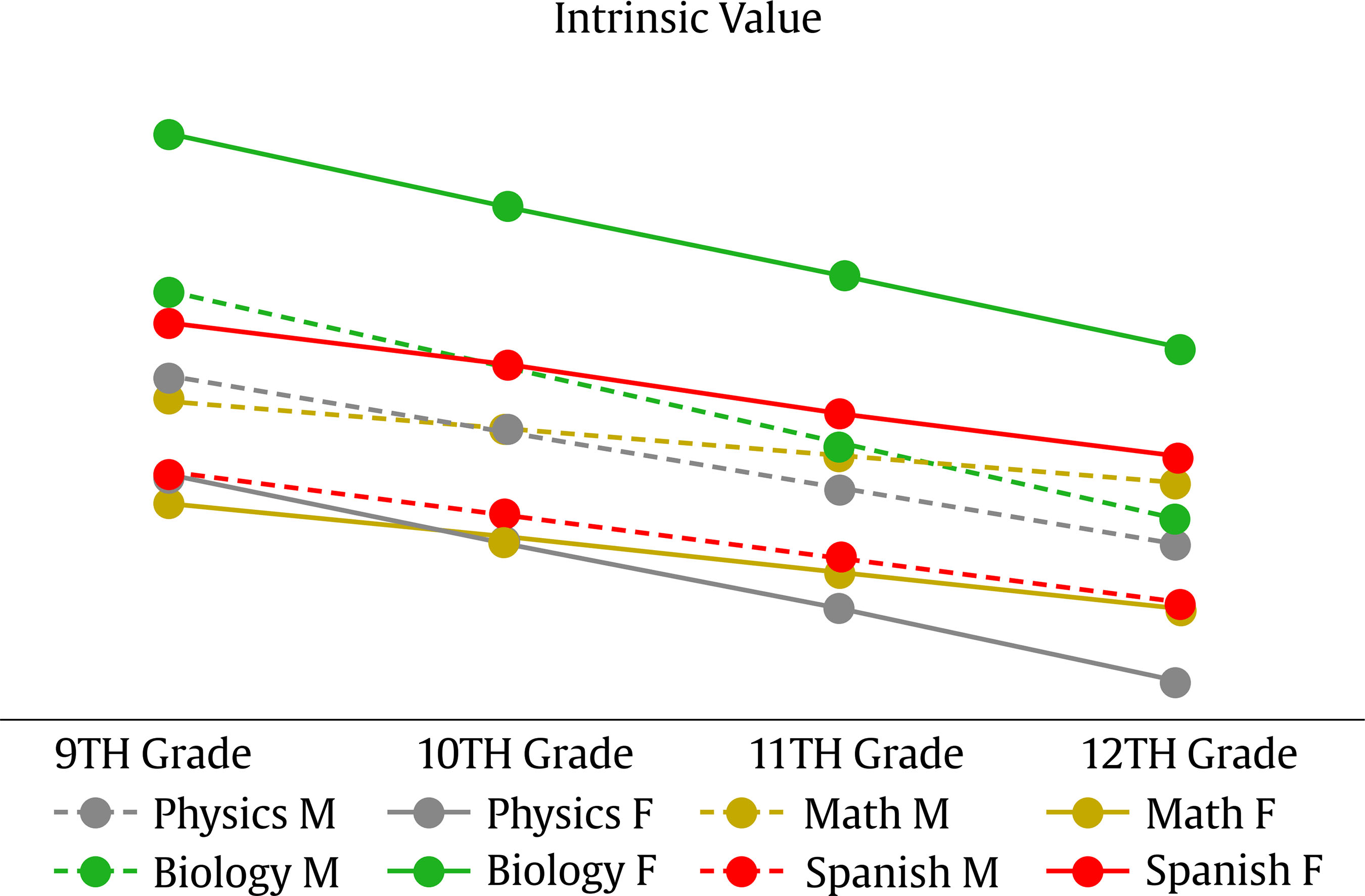

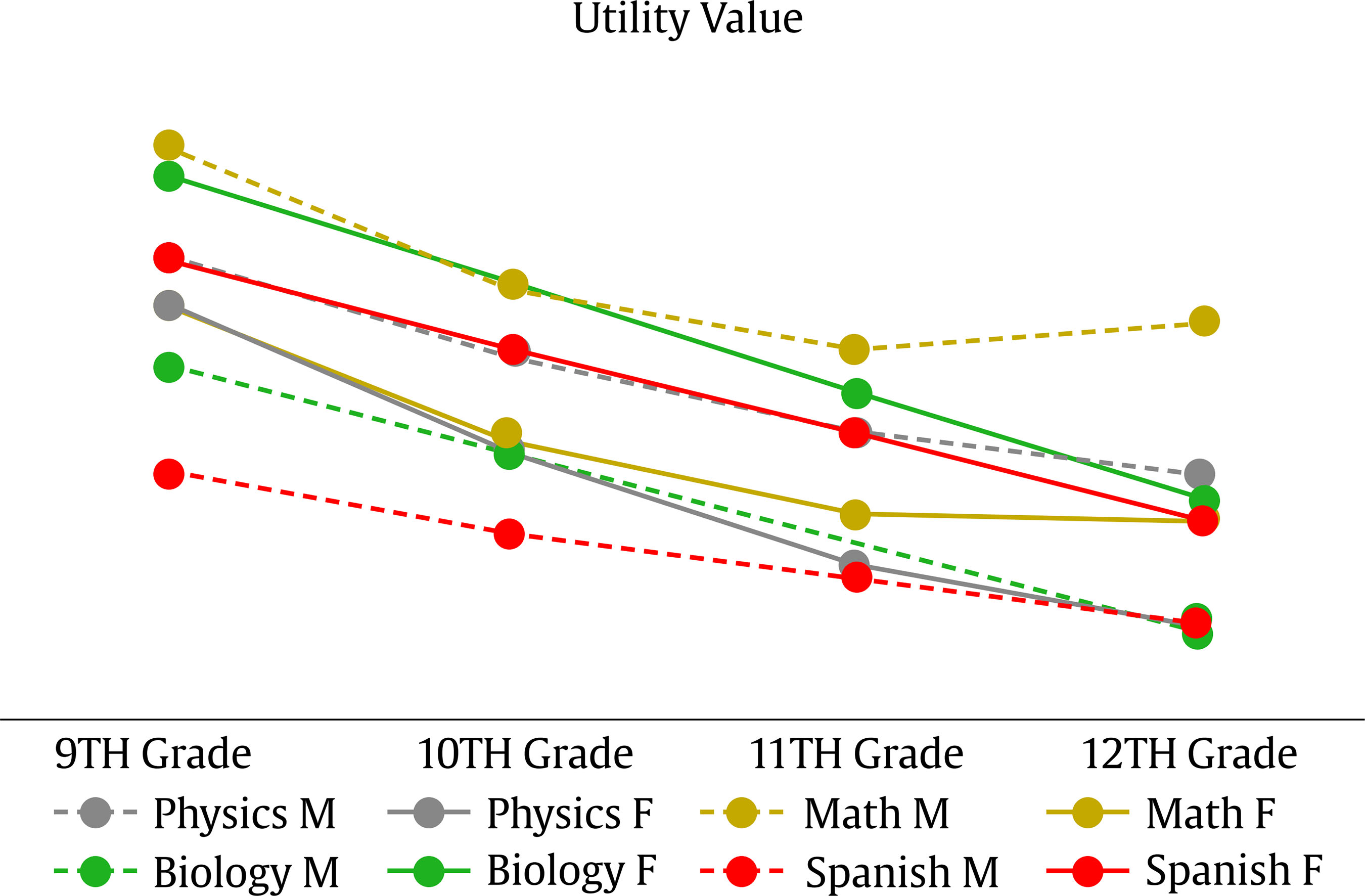

Correspondence: msainzi@uoc.edu (M. Sáinz).In recent decades, women in most Western countries have remained underrepresented in several fields of the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) pathway (UNESCO, 2021). Men, on the other hand, remain underrepresented in university studies associated with the provision of care and education. Students’ motivational beliefs are key factors shaping students’ achievement, course-taking, and career-related choices (Jiang et al., 2020; Wigfield & Eccles, 2020). In Spain, during the high school years males tend to display higher self-competence beliefs, interest, and aspirations in STEM fields (Sáinz & Upadyaya, 2016; Sáinz et al., 2021), whereas females prefer STEM and non-STEM domains involving the development of nurturing roles, such as teaching, medicine, and nursing. This career interest’s pattern is observed even when academic achievement is controlled for (Sáinz & Malpica, 2023). Interestingly, these career interests mirror the internalization of societal gender norms and expectations among Spanish youth. Over the last two years of high school (Baccalaureate) students choose to specialize in one of the five Baccalaureates available in the curriculum: Science, Technology, Humanities, Social Sciences, or Arts. This specialization process leads males and females to develop gender-biased interests in subject areas and career pathways before and after they begin the Baccalaureate (Sáinz & Gallego, 2022). In fact, at this educational stage gender disparities can be observed in the choice of Baccalaureate, with males being more likely than females to show interest in math or science-related activities or to choose the Technology Baccalaureate (Ministry of Education [MEFP, 2024]). For this reason, looking at the choices students make during the transition to non-compulsory secondary education (Baccalaureate) could be a good opportunity to see how interests translate into choices. Theoretical Background The Expectancy and Value (E-V) theory of achievement motivation is one of the most comprehensive theoretical frameworks used to analyze developmental trajectories of students’ motivation over time (Eccles & Wigfield, 2024; Urhahne & Wijnia, 2023). The theory is based on two main components: expectancy and value (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020; Wigfield et al., 2020). In line with this theory, students will choose subject areas where they think they can excel (they have a high self-concept of competence) and that have a high value for them (Wigfield & Eccles, 2020; Wigfield et al., 2020). Whereas expectancy beliefs refer to the extent to which a person feels that they can be successful in a given task, value beliefs are based on the importance the person attaches to carrying out that task. Eccles and their collaborators (Wigfield et al., 2020) initially distinguished the construct “expectancies for success” from the construct “self-concept of ability” (SCAs). While expectancies for success refers to people’s beliefs about how well they will do on an upcoming task, the SCA factor refers to people’s domain-specific assessment of their current competence or ability. Although both constructs are theoretically different, they overlap empirically. For this reason, many studies have treated them as a single construct. However, in the present study we focus on both constructs with the purpose of examining developmental patterns of motivation over time and across the observed subject areas. The value component refers to the value that people ascribe to a task, which includes the following four sub-components (Eccles et al., 2023): interest value (enjoyment of the task), utility value (how useful it is), attainment value (how important it is to complete the task), and cost value (negative factors involved in task completion). In contrast with other value beliefs, the cost value has been less comprehensively studied and less operationalized than the other task value constructs (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020). When it comes to achievement, researchers have systematically demonstrated that ability self-concepts or expectancies may matter more than task values (Lee et al, 2024; Wang et al., 2019). Yet, when it comes to career choices, interest may matter more than ability self-concepts, above all in the math domain (Guo et al., 2015; Lauermann et al., 2017). In this regard, Lauerman et al. (2017) found that math self-concept could not compensate for low levels of interest when determining the likelihood of attaining a math-related career. In the present study, we will focus on two elements of the value component: intrinsic value (intrinsic motivation) and utility value (extrinsic motivation). The E-V and the most recent update of the theory (Situated Expectancy-Value) has been the theoretical basis for much work on gender differences in motivation (Eccles & Wigfield, 2024). In fact, it is recognized how gender role stereotypes are an aspect of adolescents’ cultural background, which affects their motivational beliefs and outcomes (Eccles, 2009). For instance, recent research drawing on E-V theory shows interesting gender relations between self-concept of STEM ability and the likelihood of enrolling in STEM majors (Jiang et al., 2020). Female students reported lower math and science self-concept of ability and were less likely to enroll in STEM majors in college than male students, even though they earned higher grades than male students in STEM courses throughout high school. Developmental Patterns of Motivation during the Transition to High School The way secondary students’ motivation develops over time shapes their academic and career choices over the course of high school years and beyond. Their self-concepts of ability and valuing of one subject are influenced by their self-concepts of ability and subjective task values in other subject areas (Wigfield et al., 2020). Previous studies show that students’ motivation tends to decrease over time (Sáinz & Malpica, 2023; Jacobs et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2024). In addition, research shows that the development of students’ motivation is domain-specific (Chow & Salmela-Aro, 2011; Lee & Kim, 2014; Yeung et al., 2011), with students experiencing a faster decline of motivation in math than in English over time. Nevertheless, the patterns of students’ motivation across the same domain can also show remarkable changes in their development over time (Raufelder et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2019). For instance, students’ English motivation experienced some decline but then a slight recovery near the end of high school (Wang et al., 2019). In addition, a positive development of motivation across different subject areas (i.e., English, German, and math) through the transition from secondary to higher education has been also observed (Arens et al., 2019; Kyndt et al., 2015). Research also shows sociocultural factors in the development of students’ motivation over the transition to higher educational (Wang et al., 2019). In this regard, a study in Korea showed how whereas math interest declined continuously from 7th through 11th grade, English self-concept decreased during the middle school years but increased during high school (Lee & Kim, 2014). The way students process information they receive about their performance has an impact on the development of their expectancies and values (Eccles & Wigfield, 2024). For instance, students evaluate how they are doing now compared to how they were doing in the past (temporal comparisons). In addition, students compare themselves to others (social comparison) or compare their performance in one domain vs another (dimensional theory) (Möller & Marsh, 2013; Wigfield et al., 2020). These comparison processes play a critical role not only in the development of individuals’ self-concepts of ability in those domains, but also in the subjective task values attached to these domains, along with the connections of these to performance and career-related choices (Wigfield et al., 2020). Gaspard et al. (2020) investigated the long-term associations of students’ beliefs and subjective task values with their course enrollments, choices, and career choice from first through twelfth grade. According to the results of their research, membership in a different trajectory, or class, predicted later course enrollments, aspirations for different careers, and career choices. Students in a class characterized by strong declines in beliefs and subjective values for math were much less likely to be in a math-related career than those with more positive math beliefs and values. At the same time, the Stage-Environment Fit theory (Eccles et al., 1993; Eccles & Roeser, 2011) emphasizes the importance of context in shaping students’ motivation, particularly when it comes to the transition from lower to higher educational stages. According to this theory, a maladjustment can arise when there is a mismatch between the opportunities of a school environment (the context) and the student’s developmental needs. Changes associated with the demands of high school (e.g., feedback from their teachers, relationship with peers, or school specialization) may also entail important changes in students’ motivation. For this reason, negative changes in students’ motivation (i.e., ability self-concepts or intrinsic values) reflect a poor fit between the student and the school context (Eccles & Roeser, 2011). However, there is a literature gap on how gender differences in motivation across core subject areas (math or Spanish) develop during the transition to Baccalaureate in Spain. With the present study, we aim at filling this research gap. The Present Study The present study focuses on four domains relevant to the curriculum of Spanish secondary education (i.e., Spanish, math, physics, and biology) in order to expand our understanding of the motivational mechanisms guiding young people’s motivation in the STEM pipeline and Spanish language during the secondary school years. Since good math competencies are a prerequisite to entering different STEM majors and occupations (González et al., 2020; Sáinz & Eccles, 2012), the analysis of developmental dynamics of motivation in math has been the focus of considerable longitudinal research (Aunola et al., 2004; Guo et al., 2015, Jiang et al., 2020; Master, 2021). However, other non-math subject areas across STEM (such as chemistry or physical science) remain under-researched. In the present longitudinal study, drawing on the main tenets of the EV theory, we develop an analysis of the developmental dynamics of motivation across Spanish and STEM subjects such as math, physical science, chemistry, or biology. Thus, further inclusion of multiple domain-specific self-concept of ability, expectancies, intrinsic values, and task values will provide a more comprehensive portrait of gender differences in the developmental trajectories of motivation. The present study aims at providing answers to the following research questions: 1. Do students’ self-concept of ability, expectancies, intrinsic values, and utility values in STEM subject areas (such as physics and chemistry, math, and biology), and Spanish change between grades 9 and 12? 2. Are the development of and changes in the different aspects of motivation similar for male and female students? Sample The sample consisted of a group of 1,805 secondary students (881 males, 924 females) enrolled respectively in the last two years of compulsory secondary education (third and fourth years of ESO) and the two years of post-compulsory secondary school (Baccalaureate). The number of students at each measurement time was as follows: Time 1 (Grade 9, N = 796), Time 2 (Grade 10, N = 796), Time 3 (Grade 11, N = 954), and Time 4 (Grade 12, N = 864). At times T1-T4 students were respectively 14, 15, 16, and 17 years old. At T4, 28.6% of the participants were enrolled in the scientific Baccalaureate, 10.3% in the humanities Baccalaureate, 30.2% in the social science Baccalaureate, 17.9% in the technological Baccalaureate, and 13% in the artistic Baccalaureate. At time T1 61% of the students had intermediate SES, while the rest of the students had respectively 20% and 19% high and low SES. While 40%, 57%, and 3% of the participants’ fathers had respectively attained university, secondary, and primary school, 42%, 55%, and 3% of the participants’ mothers had respectively achieved university, secondary, and primary school. Procedure Informed consent and authorization were obtained from the school authorities (including the parents’ association) prior to collecting the data associated with our longitudinal research. All participants completed the questionnaires during school hours in the springs of 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. Initially, more than 50 public schools from the metropolitan areas of Madrid and Barcelona were randomly selected and targeted, but only 10 schools wanted to engage in a long-term commitment. In order to promote the engagement of schools, school principals were informed that an annual report and a seminar with main findings would be delivered at the end of every academic year to provide return on the results of the project. During the four time measurements students were given the opportunity to leave the room if they did not want to participate in the study. After a brief introduction in which the researchers spoke about the purpose of the study, the students responded to the questionnaire, which took around 35-45 minutes. Participation in the study was voluntary, with no remuneration or course credits. Both the anonymity and confidentiality of the data collected were assured. Prior to the collection of data, the research received the approval of the university IRB (Institutional Review Board). Data details are available and can be accessed in the following link: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4803-1597 This study was not pre-registered. The research complies with ethical standards since approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study, their parents, and legal guardians. Measurements Self-concept of Ability in Math, Biology, Physical Science & Chemistry, and Spanish Students’ self-concept of ability was measured with a translated version of Eccles and Harold (1994) scale (Sáinz & Eccles, 2012). This scale consists of 5 items, with values ranging between 1 (low competence) and 7 (high competence). Cronbach’s reliability was respectively .81 for math, .90 for biology, .91 for physical science & chemistry, and .84 for Spanish. Barlett’s test of spheracity is statistically significant for math, χ2(10) = 2037.560, p < .001, biology, χ2(10) = 2708.897, p < .001, physical science & chemistry, χ2(10) = 3185.733, p < .001, and Spanish, χ2(10) = 1823.846, p < .001, measures. Kaiser’s measure for sample of adequacy was respectively .80 for math and .80 for Spanish. The items explain 62.6% for math, 62.32% for Spanish, 72.23% for biology, 74% for physical science & chemistry of the variance. Intrinsic Value in Math, Biology, Physical Science & Chemistry, and Spanish Students’ intrinsic value was measured with a translated version of Eccles & Harold (1991) scale. This scale consists of 3 items with values ranging between 1 (low intrinsic value) and 7 (high intrinsic value). Cronbach’s reliability were respectively .91 for math, .93 for biology, .94 for physical science & chemistry, and .88 for Spanish. Barlett’s test of sphericity is statistically significant for math, χ2(3) = 1765.840, p < .001, biology, χ2(3) = 2081.687, p < .001, physical science & chemistry, χ2(3) = 2284.776, p < .001, and Spanish, χ2(3) = 1376.859, p < .001, measures. Kaiser’s measure for sample of adequacy was respectively .73 for math, .74 for biology, and .74 for physical science & chemistry, and .70 for Spanish. They explained respectively 85%, 88%, 89%, and 80% of the variance. Utility Value in Math, Biology, Physical Science & Chemistry, and Spanish Students’ utility value of the different subject areas was measured with a translated version of Eccles and Harold’s (1991) scale. This scale consists of 2 items with values ranging between 1 (low competence) and 7 (high competence). Cronbach’s reliability was respectively .88 for math, .91 for biology, .92 for physical science & chemistry, and .87 for Spanish. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant for math, χ2(1) = 747.586, p < .001, biology, χ2(1) = 953.807, p < .001, physical science & chemistry, χ2(1) = 993.639, p < .001, and Spanish, χ2(1) = 695.321, p < .001, measures. Kaiser’s test of sampling adequacy was respectively .50 for math, .50 for biology, .50 for physical science & chemistry, and .50 for Spanish. It explained 89% of the variance for math, 88% for Spanish, 92% for biology and 92% for physical science. Expectancies in Math, Biology, Physical Science, and Spanish Students’ expectancies in math and language was measured with a translated version of Eccles and Harold’s (1991) scale. This scale consists of 3 items with values ranging between 1 (low competence) and 7 (high competence). Cronbach’s reliability were respectively .80 for math, .87 for biology, .88 for physical science & chemistry, and .83 for Spanish. Barlett’s test of sphericity is statistically significant for the math, χ2(3) = 779.535, p < .001, biology, χ2(3) = 1205.938, p < .001, physical science & chemistry, χ2(3) = 1265.337, p < .001, and Spanish, χ2(3) = 889.357, p < .001, measures. Kaiser’s measure for sample of adequacy was respectively .68 for math, .73 for biology, .73 for physical science & chemistry, and .70 for Spanish. It explained 72% of the variance for math, 74.28% for Spanish, 80% for biology and 81% for physical science & chemistry. Performance in Math, Biology, Physical Science & Chemistry, and Spanish Grades in the different domains were gathered for the different subject areas, with values ranging between 1 (failed) to 5 (excellent). Analytical Strategy The research questions were analyzed using latent growth curve modeling (LGM; Duncan et al., 1997) with multiple group procedures (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). The analyses were carried out in two steps. First, to investigate the extent to which students’ motivation (e.g., self-concept of ability, expectancies, intrinsic value, and utility value) in different domains (e.g., physics and chemistry, math, biology, and Spanish) change over time, LGMs were carried out separately for each aspect of motivation in each academic domain. Simultaneously, the multi-group procedure was included in the analyses so that the latent growth curves were estimated separately for male and female students in each model. In these models, we estimated the mean levels of students’ self-concept, expectations, intrinsic value, and utility value in different domains (intercept), their linear and quadratic growth (linear and quadratic slope), and individual variation across these scores. The intercepts were specified by setting the loadings of the four observed values of the different aspects of motivation in each domain to 1; the linear slopes were specified by setting the loadings of the four observed values to 0, 1, 2, and 3; and the time scores for the quadratic slopes were the squared values of the linear time scores. The residual variances of the observed variables were allowed to be freely estimated. The statistical analyses were performed using Mplus (Version 8; Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017) with the missing data method and MLR estimator. Goodness-of-fit was evaluated using four indicators: χ2 test, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). In the final model, all the statistically non-significant associations were fixed to zero. Development of Self-Concept, Expectancies, Intrinsic Value, and Utility Value The means and standard deviations of all the variables are shown in Table 1. The full correlation matrix is available from the authors upon request. First, multi-group LGCs were constructed separately for students’ expectations, self-concept of ability, intrinsic value, and utility value in physics, math, biology, and Spanish to investigate average change and inter-individual variation across the mean components in students’ expectancies and values. All the models were constructed across four measurement points. The model construction across the four measurement points was started by testing a model that contained three growth components: initial level, linear slope, and quadratic slope. All the final models included only those growth components that were either statistically significant, showed variation, or both at least in one of the multi-group assemblies (e.g., males or females). Variance parameters that were not statistically significant were fixed to zero. The findings for students’ expectancies showed that students’ expectancies in all the domains first decreased during the school years, with one exception: female students’ expectancies in Spanish remained high and stable over the school years (Table 2, Figure 1). In most cases, the variances of the initial levels and linear trends of students’ expectations were statistically significant, indicating significant individual differences in the initial level and development of expectancies. The results showed further that among male students, the quadratic trend of expectancies in math and Spanish was significant, indicating subsequent increases in male students’ expectancies in these domains. Among female students, their expectancies in math started to increase towards the end of the study. Table 2 Latent Growth Components of the LGC Models (SEs in the Parentheses)   Note. *p < .001, **p < .01, ***p < .10; 01 = fixed to zero. The results for students’ self-concept of ability showed that students’ self-concepts in all the domains first decreased during the school years, with one exception: female students’ self-concepts in Spanish remained high and stable during the school years (Table 2, Figure 2). In most cases, the variances of the initial levels and linear trends of students’ self-concepts were statistically significant, indicating significant individual differences in the initial level and development of self-concepts. The results showed further that among male students, the quadratic trend of self-concepts of Spanish was significant, indicating subsequent increases in male students’ self-concepts in this domain. The findings for students’ intrinsic values showed that students’ intrinsic values in all the domains first decreased over the school years (Table 2, Figure 3). In most cases, the variances of the initial levels and linear trends of students’ intrinsic values were statistically significant, indicating significant individual differences in the initial level and development of intrinsic values. The results showed further that among male students, the quadratic trend of intrinsic values in math was significant, indicating subsequent increases in male students’ intrinsic values in this domain. Interestingly, female students attached the highest intrinsic value to the subject areas of biology and Spanish, with a higher decline in the intrinsic value attached to biology than to the one attached to Spanish over time. However, they also attached the lowest intrinsic value to math and physics. Male participants attached the lowest intrinsic value to Spanish and math, but the highest intrinsic value to biology and physical science & chemistry. The results for students’ utility values showed that students’ utility values in all the domains first decreased over the school years (Table 2, Figure 4). In most cases, the variances of the initial levels and linear trends of students’ utility values were statistically significant, indicating substantial individual differences in the initial level and development of utility values. The results showed further that among male students, the quadratic trend of utility values in math was significant, indicating subsequent increases in male students’ utility values in this domain. Among female students, their utility values in physics and math started to increase towards the end of the study. Next, students’ performance in each domain was added as covariates in each model (Table 3). The results showed, as expected, that in each domain academic performance was positively associated with the initial level of expectancies, SCA, intrinsic value, and utility value. In addition, for females, performance in each domain was negatively associated with the linear slope of Spanish expectancies, and SCA in math, biology, and Spanish, indicating a faster decline in motivation. Moreover, performance in math was positively associated with expectancies in the case of males and utility values in the case of females, indicating a slower decline in motivation. Table 3 Latent Growth Model with Grades in Each Domain as Covariates   Note. *p < .001; **p < .01; ***p < .10; 0* = fixed to zero. The present study contributes to the literature by providing data about how Spanish secondary school students’ expectancies and value beliefs evolve during the transition to the Baccalaureate. The analysis of the development of different components of the E-V theory across various STEM subject areas (math, biology, and physical science & chemistry) as well as Spanish is one of the main contributions of the research. For this purpose, we focused on two constructs of the expectancy beliefs (self-concept of ability and expectancies) component as well as on two constructs of the subjective task value component (intrinsic and utility value). In addition, performance in all the domains over the time was included as a covariate in the different growth models. In general terms, the results confirm previous longitudinal research conducted in other contexts drawing on E-V theory, showing changes in students’ motivation over time (Eccles & Wigfield, 2024; Fredricks & Eccles, 2002; Gaspard et al., 2020). As highlighted by the stage-environment fit theory, these changes observed in students’ motivation can be associated with the transition from junior to senior secondary education (Roeser et al., 1999). That is, during the process of school specialization students compare their achievement in the different subject areas (dimensional comparison) of the curriculum, but some students are not mature enough to make this decision. This transition period together with the context of higher secondary schooling offers challenges and opportunities for students (Kyndt et al., 2015). Interestingly, motivational beliefs (interests, intrinsic values, expectancies, and self-concepts of ability) in the observed subject areas translate into choices, but these choices also shape students’ motivational beliefs. The ontogenesis of students’ motivation across the observed subject areas suggests individual differences across the different constructs of the E-V theory under research and the considered domains. Regarding the results associated with the different constructs of the E-V component, significant individual differences in the initial level and development of the different E-V components arose across the different constructs. In line with previous studies (Jacobs et al., 2002; Jiang et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2021), motivation in the different subject areas tends to decrease over time across the different constructs. However, these declines are higher for the value-related constructs than those of the expectancy component. Gender Differences in the Developmental Patterns of Motivation Aligned with our expectations, we have observed gender disparities in the development and changes in motivation varied across the different subject areas (Eccles & Wigfield, 2024; Gaspard et al., 2020). These differences among males and females are congruent with gender role stereotyping (Eccles & Wigfield, 2024; Jiang et al., 2020). When considering the two constructs associated with the expectancy component (self-concept of ability and expectancies), we observed remarkable gender differences in the changes and development of motivation in some subject areas. With regard to the results related to SCA and expectancies, males and females experienced declines in both motivation indicators across the different subject areas. However, among females both SCA and expectancies in Spanish remained high and stable across the different measurement points. Interestingly, for males, expectancies in math and Spanish increased over time, while for females, expectancies in math started to increase at the end of the measurement points. These findings suggest the important role that Spanish plays in the formation of students’ expectancy-related beliefs over the course of secondary education. However, math seems to play an outstanding role in shaping males’ expectancy beliefs throughout secondary school years. Similarly to the rest of motivation constructs, the intrinsic and utility values attached to the different subject areas tended to decline over time for both males and females. However, in comparison to their male counterparts, females experienced a lower decline than their male counterparts in the intrinsic value attached to biology and a greater decrease in the value attached to physical science & chemistry. This finding could explain girls’ preference for STEM fields highly associated with biology. In a similar way the ontogenesis of the utility value component tended to decline over time for all the subject areas. Strikingly, for males the utility value attached to math increased at the end of the study, but for females the utility value attached to math and physical science & chemistry experienced a slight increase. Probably, females enrolled in the two STEM-based Baccalaureates attach higher extrinsic value that these domains have for the choices they would do in the future. Adding performance in the different domains as a covariate confirms previous results and indicates how the development of motivation differs for males and females, especially with regard to self-perception beliefs across all the considered STEM domains. All these findings associated with the developmental dynamics of the different motivation constructs also support the tenets of the comparison theory when it comes to the evaluation of the different aspects of motivation across the different subject areas (Wigfield et al., 2020). The fact that at grades 11 and 12 (times 3 and 4) students were enrolled in Baccalaureate and had already selected one out of the five available academic tracks in could explain some of the findings. At this educational stage peer comparison plays an important role in the decision-making process of career choices, which explains how students’ patterns of motivation develop showing changes or stability. These findings may have implications in career-related choices, since students may take these motivational patterns as a reference to guide their academic decisions and preferences. Guidelines for Interventions In light of the previous results, more educational resources are needed to increase women’s interest in math and physical science & chemistry, as well men’s interest and SCA in Spanish and biology. Intervention programs are necessary during high school to increase girls’ motivation in those STEM subject areas where men have traditionally been perceived as more competent than women (that is, math and physical science & chemistry). Furthermore, more initiatives should be conducted to increase the subjective-related value of some subject areas, particularly biology and Spanish, since participants attach less extrinsic value to these subjects than to math and physical science & chemistry. Intervention-oriented research suggests that utility value is the most malleable subjective task value component. For this reason, it is the most likely E-V component to change during interventions (Harackiewicz et al. 2014). Consistently with the obtained findings, a career guidance strategy should also be implemented with a gender perspective across the different educational stages to help students make meaningful career-related decisions free from the influence of gender biases. Examining how these motivational patterns develop during the transition to high school specialization will offer insights into the capacity of different groups of students to successfully adapt to the changing educational environments. Special attention should be given when students go into high school. Moreover, adopting a personalized trajectory-specific intervention strategy rather than a universal approach may favor the design of efficacious interventions for addressing gender differences in motivation-related outcomes across the different subject areas. The results of the present study also suggest the importance of training secondary teachers and school advisors on how motivation in the different subject areas develops over time and how the different developmental patterns are congruent with gender roles and stereotypes. It is imperative that these educational agents acquire strategies on how to promote inclusive school environments to avoid reproducing gender biases in school achievement and study choices. Likewise, provided intrinsic and utility values tend to decline at an early stage, early interventions should be implemented to foster long-term engagement among students. In addition, since girls tend to have higher declines in physical science and math values, promoting a growth mindset to challenge stereotypes about STEM through initiatives that promote the presence of female role models in the learning process of these subject areas. It is also crucial to promote parental engagement to support both intrinsic values and performance development, particularly in those subjects that have lower intrinsic value. Academic performance seems to be strongly associated with initial motivation levels. For this reason, academic support programs (i.e., peer mentoring or learning assistance) should be implemented and aligned with motivational coaching. For instance, the design of personalized coaching programs to promote self-perceptions of ability and expectancies, ideally aligned with gender-specific trends (i.e., to enhance girls’ self-perception of math ability and boys’ self-perceptions of Spanish abilities). The utility value attached to the subject areas can be enhanced by associating subject content with students’ future goals and identities. In addition, teachers should acquire strategies to avoid gender differences in the intrinsic value students attach to the different subject areas and increase students’ intrinsic value attached to learning those subject areas and academic pathways with low intrinsic value (for instance, in the present study, boys and girls reported the lowest intrinsic values in math). Limitations and Future Research Among the limitations of the study, multicollinearity among the variables in most of the cases made the multi-group parallel LGCs analysis difficult. Future research is needed on the motivation dynamics in domain-specific areas of students who transit into higher education from high school. Future research in Spain should continue examining longitudinal patterns of motivation development of young people during and beyond secondary school education. The development of cross-lagged effects across the different constructs and domain-specific subject areas should be further analyzed. In addition, future investigation drawing on EV theory should include cost-related measurements in order to look at the developmental patterns of negative consequences (costs) of investing time and effort in a task related to the subject areas under study over time. It would be also interesting to analyze the development of students’ motivation in other subject areas that have been neglected by literature, such as philosophy, history or social sciences. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank the participants and school principals for their engagement in this research. Cite this article as: Sáinz, M. & Upadyaya, K. (2026). Developmental dynamics of expectancy and value beliefs in stem and language: Gender stereotyping influences. Psicología Educativa, 32, Article e260448. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a5 Funding The present research received funds from two consecutive grants of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (FEM2011-2014117) and the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness FEM2014-55096-R). References |

Cite this article as: Sáinz, M. & Upadyaya, K. (2026). Developmental Dynamics of Expectancy and Value Beliefs in STEM and Language: Gender Stereotyping Influences. PsicologĂa Educativa, 32, Article e260448. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2026a5

Correspondence: msainzi@uoc.edu (M. Sáinz).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS