Meta-Analysis on Family Quality of Life in Autism Spectrum Disorder

[Meta-análisis sobre la calidad de vida familiar en el trastorno del espectro autista]

Ana Muiño1, Guido Corradi2, & Alejandro Arrillaga1

1Universidad Villanueva, Madrid, Spain; 2BEATLES Research Group, University of Balearic Islands, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/clh2026a1

Received 18 November 2024, Accepted 7 November 2025

Abstract

Background: The Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) significantly affects family quality of life (FQoL), with child age and symptom severity playing key roles. This meta-analysis examines how these factors relate to FQoL. Method: A systematic search was conducted in APA PsycInfo, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, PSICODOC, MEDLINE, and EBSCO databases. Up to 2024, no meta-analyses had examined these variables. Fifteen articles met the inclusion criteria, and their methodological quality was evaluated following PRISMA guidelines. Results: Findings indicate a moderate positive correlation between child age and FQoL, suggesting that FQoL tends to improve as children grow older. Conversely, ASD severity shows a negative but non-significant association with FQoL. Family support and cohesion emerge as crucial influencing factors. Conclusions: This study highlights the importance of considering both ASD characteristics and family psychosocial resources, emphasizing the need for adaptive, family-centered support strategies.

Resumen

Antecedentes: El trastorno del espectro autista (TEA) afecta significativamente la calidad de vida familiar (CVF), donde la edad del niño y la gravedad de los síntomas desempeñan un papel fundamental. Este metaanálisis examina la relación entre estos factores y la CVF. Método: Se realizó una búsqueda sistemática en las bases de datos APA PsycInfo, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, PSICODOC, MEDLINE y EBSCO. Hasta 2024, ningún metaanálisis había examinado estas variables. Quince artículos cumplieron los criterios de inclusión y su calidad metodológica se evaluó siguiendo las directrices PRISMA. Resultados: Los hallazgos indican una correlación positiva moderada entre la edad del niño y la CVF, lo que sugiere que la CVF tiende a mejorar con la edad. Por el contrario, la gravedad del TEA muestra una asociación negativa, aunque no significativa, con la CVF. El apoyo y la cohesión familiar emergen como factores de influencia cruciales. Conclusiones: Este estudio destaca la importancia de considerar tanto las características del TEA como los recursos psicosociales familiares, destacando la necesidad de estrategias de apoyo adaptativas y centradas en la familia.

Palabras clave

Trastorno del espectro autista, Edad del niño, Gravedad de los sĂntomas, Calidad de vida familiar, MetaanálisisKeywords

Autism spectrum disorder, Child age, Symptom severity, Family quality of life, Meta-analysisCite this article as: Muiño, A., Corradi, G., & Arrillaga, A. (2026). Meta-Analysis on Family Quality of Life in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Clinical and Health, 37, Article e260715. https://doi.org/10.5093/clh2026a1

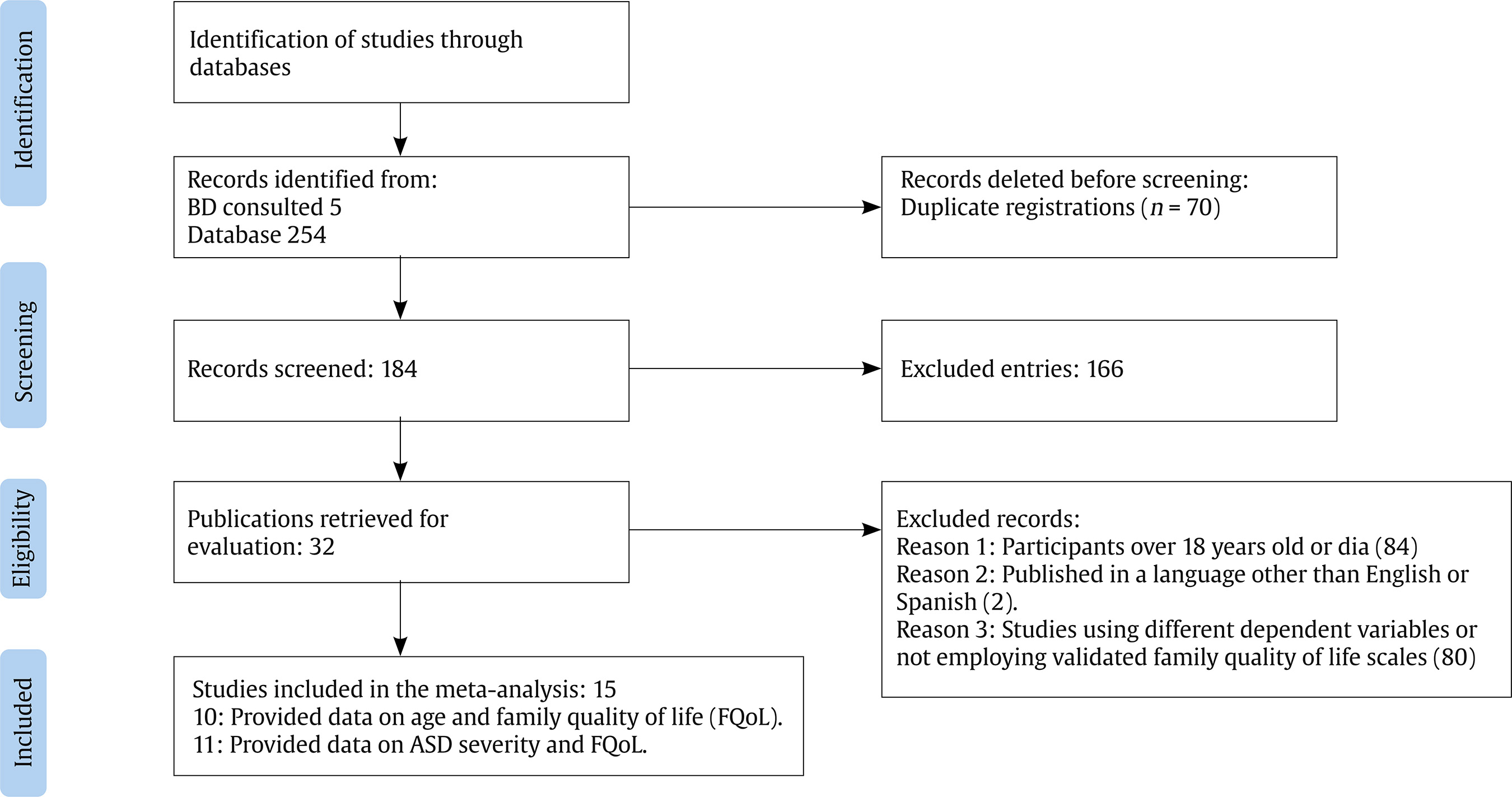

Correspondence: ana.muino@villanueva.edu (A. Muiño).The Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition affecting approximately 1 in 54 children in the United States (CDC, 2020). This figure, widely cited in international literature, is frequently used as a reference point due to the large-scale surveillance and regular updates provided by the U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. The increasing prevalence of ASD underscores the growing relevance of understanding how the condition affects not only individuals but also their families, particularly in terms of family quality of life (FQoL). ASD is characterised by core symptoms such as difficulties in communication, social interaction, and flexibility in routines. These symptoms vary significantly in severity, from mild to severe, and contribute to varying family experiences and challenges (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In addition to core symptoms, individuals with ASD often exhibit comorbid conditions, which further complicate caregiving. These comorbidities can be categorized into three domains: neurological (e.g., epilepsy, occurring in 5-38% of individuals with ASD; Operto et al., 2021), behavioral (e.g., ADHD, reported in 28-44% of cases, as well as self-harm, aggression, and defiance; Fernández-Alvarado & Onandia-Hinchado, 2022), and physical (e.g., gastrointestinal issues and sleep disorders), all of which further exacerbate family challenges. These comorbid conditions significantly impact family functioning and QoL, often increasing the stress and caregiving burden on families (Gray, 2002). Parents of children with ASD experience significantly higher levels of stress and burnout compared to parents with typically developing children (Dykens, 2015). The diversity of symptoms and their severity vary widely among individuals, ranging from those with ordinary intellectual and communication skills to those with severe disabilities (Lord et al., 2020). The DSM-5 categorises ASD into three levels of severity: Level I (requiring support), Level II (requiring substantial support), and Level III (requiring very substantial support), further illustrating this variability (APA, 2013). Such a diversity in presentation complicates the assessment of its impact on QoL. Quality of life, traditionally measured at the individual level, has shifted towards a broader conceptualisation that includes the family unit. This shift recognises that the impact of ASD extends beyond the individual, influencing family dynamics, including emotional FQoL, social functioning, and financial stability (Schalock, 2002). The World Health Organization’ (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) provides a comprehensive framework for understanding health and disability, integrating contextual, social, and personal factors affecting health and FQoL (ICF, 2000). This broader approach to QoL is part of a growing trend in health research that acknowledges the importance of family-centred perspectives. Numerous studies have demonstrated that parents of children with ASD have a lower FQoL compared to parents with typically developing children or children with other disabilities (Lecavalier & Schwartz, 2009; Ni’matuzahroh et al., 2022). Stress in caregivers is a significant factor impacting their FQoL, as documented in various research studies (Lecavalier & Schwartz, 2009). Factors contributing to this reduced FQoL include elevated parental stress, economic hardship, social isolation, mental health issues, and communication challenges (Dykens, 2015). The age of the child with ASD and the presence of comorbidities also significantly influence FQoL (Ni’matuzahroh et al., 2022). Protective factors can mitigate these challenges, enhancing FQoL. These include access to early intervention services, robust social and emotional support networks, effective parental coping and stress management strategies, financial and material resources, and parent education and training (Ramírez-Coronel et al., 2020). Although numerous studies have examined how ASD affects FQoL, the findings remain inconsistent due to methodological variation and heterogeneity in clinical and demographic profiles. This inconsistency highlights the need for further investigation to better understand the factors that influence FQoL in the context of ASD. This meta-analysis aims to address these gaps by offering a comprehensive and consolidated perspective on the factors that most significantly influence FQoL in the context of ASD. Specifically, the study seeks to quantify the overall impact of ASD on family QoL by identifying potential moderating factors, such as the severity of the diagnosis and the age of the child. In doing so, it intends to clarify the relationship between ASD and FQoL by synthesising findings from previous, and often contradictory, studies. Furthermore, it examines the extent to which clinical characteristics—particularly symptom severity and child age—affect FQoL, thereby contributing to a more nuanced understanding of these influences. By consolidating current evidence, this study aims to reduce existing inconsistencies in the literature and provide a solid empirical foundation for the development of family-centred interventions that promote the FQoL of both children with ASD and their families. Research was ethically, responsibly, and legally conducted. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Sources and Search Strategies To identify papers, we searched the APA PsycInfo, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, PSICODOC, MEDLINE and eBook Collection (EBSCO). No year of publication restrictions were applied. The search strategy in databases included terms such as “autism”, “ASD”, “autism spectrum disorder”, “Asperger’s”, “Asperger’s syndrome”, “autistic disorder, “Asperger’s” and “family quality of life”, which were combined using the Boolean operator “AND” and “OR” to ensure retrieval of articles that addressed both concepts simultaneously. The combinations of terms used were as follows: Autism* OR ASD* OR autism spectrum disorder* OR Asperger’s* OR Asperger’s syndrome* OR autistic disorder* OR, Asperger’s* AND family quality of life. Study Selection Criteria The aim was to integrate and quantify the empirical findings available in the literature to obtain a clearer and more coherent picture of this relationship. The literature search was conducted without date restrictions and was finalised in December 2024. To be included in the meta-analysis, studies had to meet the following criteria: 1) participants: studies included children and adolescents under 18 years of age with a confirmed diagnosis of ASD, consistent with diagnostic criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or other validated tools, such as structured interviews or diagnostic questionnaires; 2) measurement tools: studies employed validated family quality of life scales, including the Family Quality of Life Scale (FQOL) or comparable instruments evaluating related constructs; 3) focus: articles specifically explored the relationship between ASD and QoLF, excluding studies primarily investigating individual quality of life or general well-being; 4) language: original empirical studies written in English or Spanish, employing observational, experimental, or survey-based methods with quantitative or qualitative analyses. Studies were excluded if: 1) did not use validated family quality of life scales, 2) were focused on participants with diagnoses other than ASD or individuals over 18 years, 3) did not include an explicit measurement of QoLF as a central construct; or 4) were duplicated or not available in full text. Screening and Selection Process This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA [Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses] guidelines to ensure a systematic, rigorous, and transparent process in the identification, selection, and synthesis of relevant studies on the impact of ASD on family quality of life (FQoL; Page et al., 2021). A total of 254 articles were initially retrieved from the selected databases. After the removal of 70 duplicate entries, 184 unique records remained for screening. During the screening phase, 166 studies were excluded based on the following criteria:

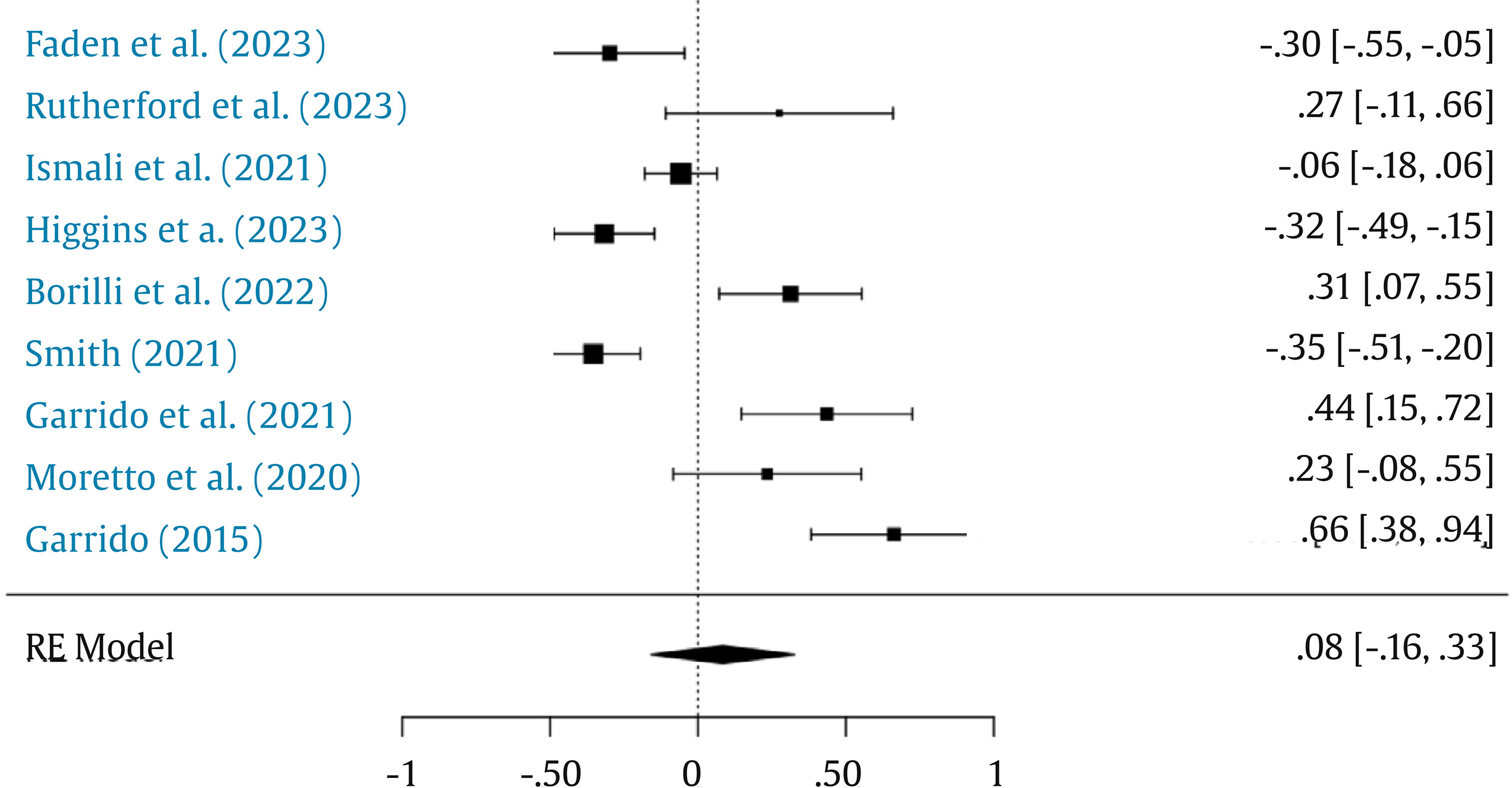

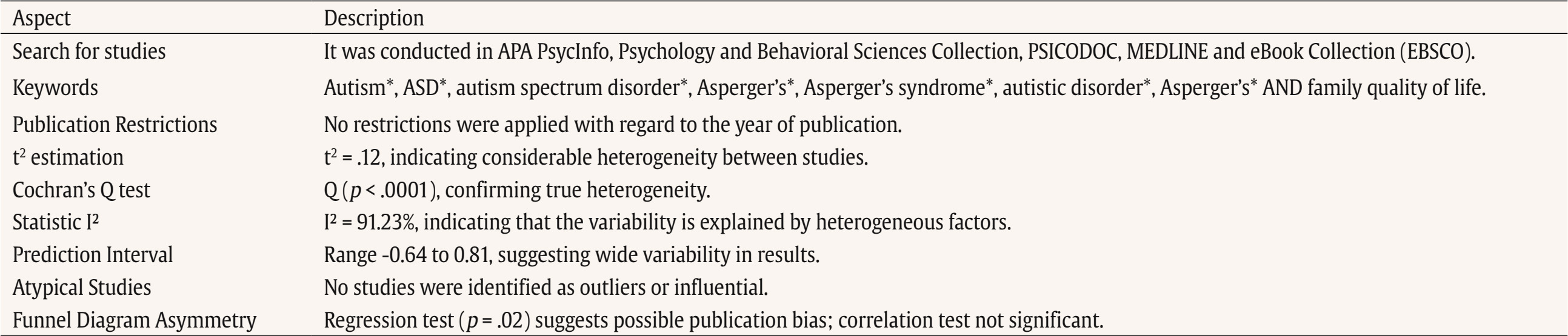

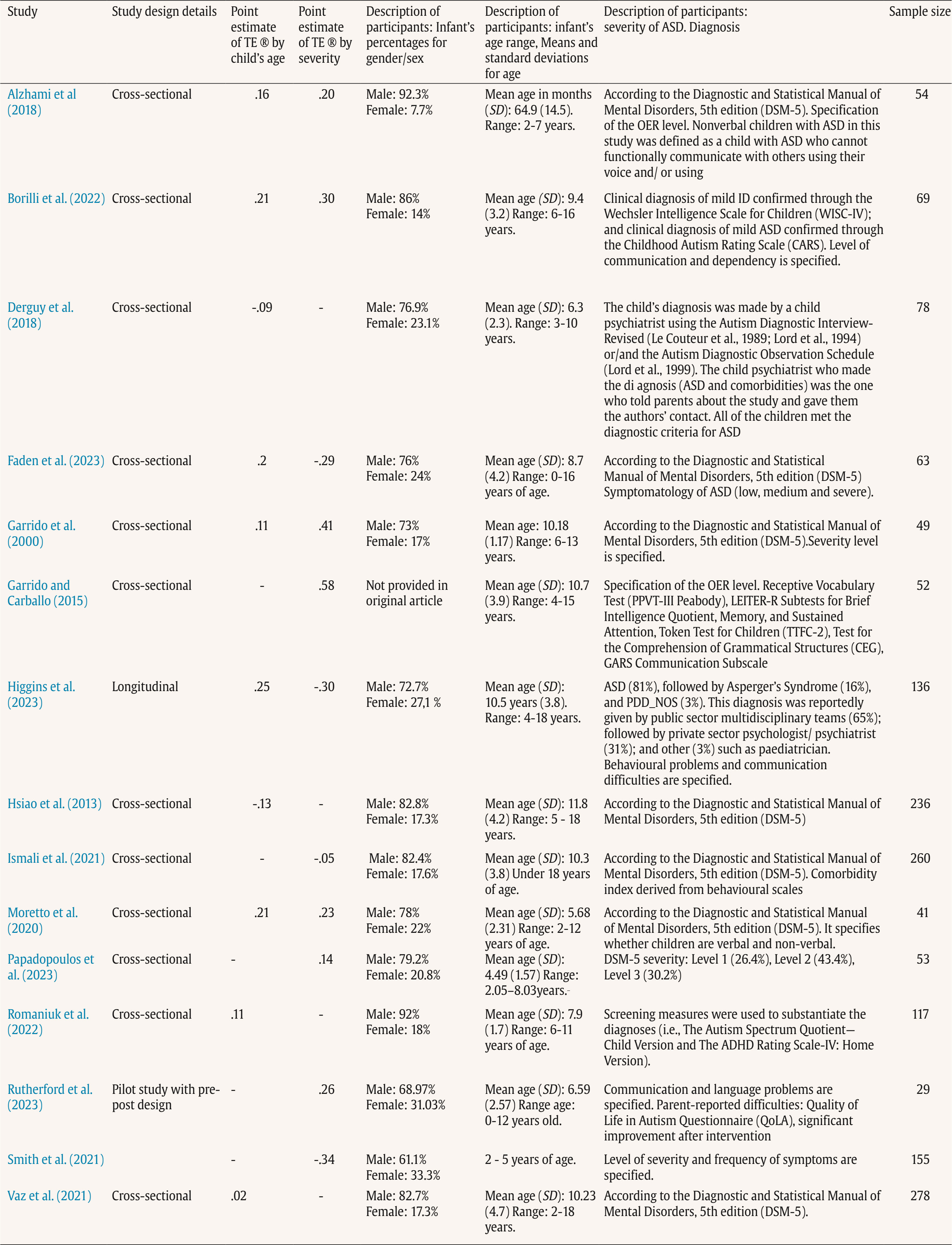

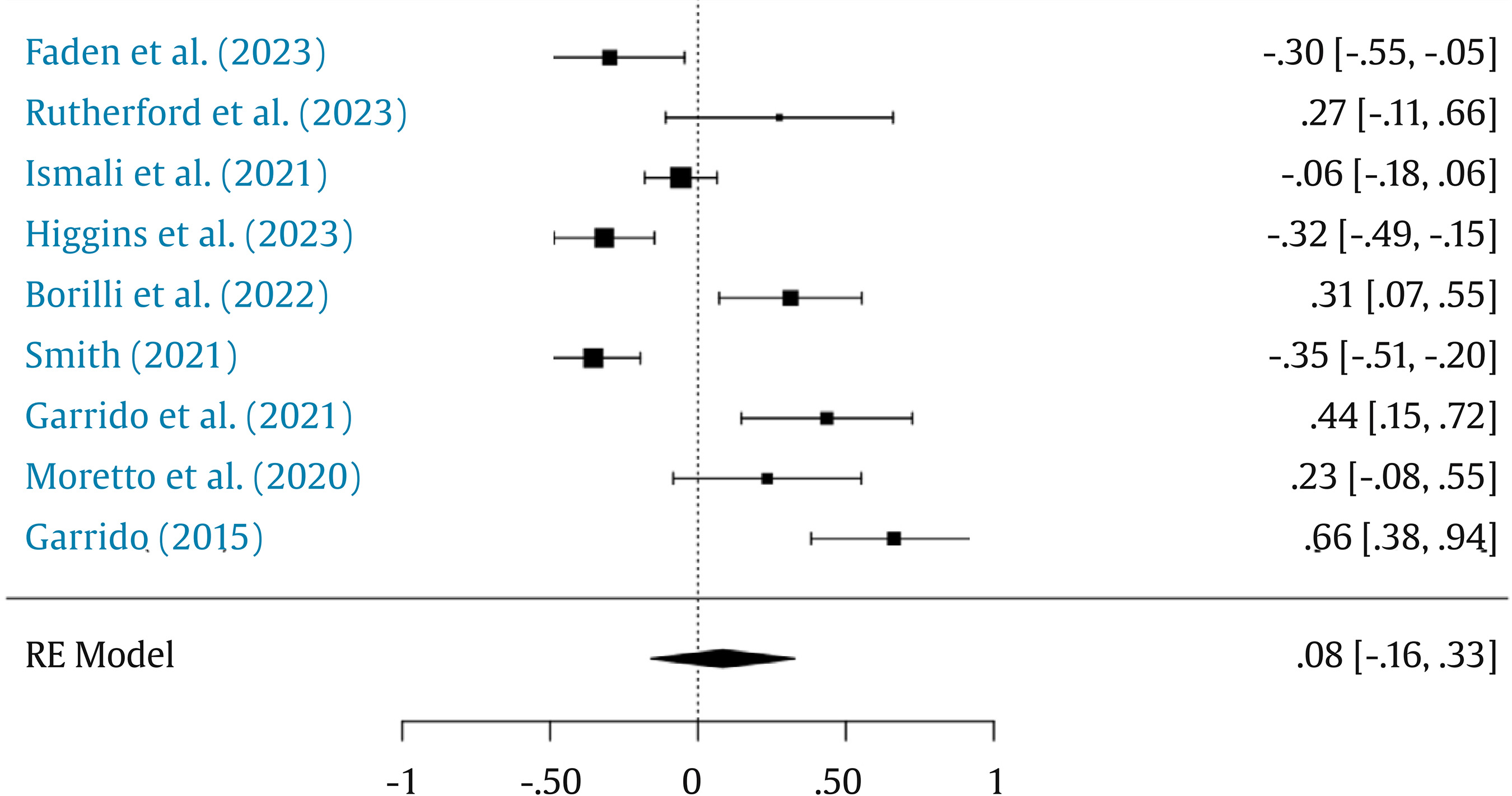

Following this initial screening, 32 articles were retained for full-text review. In addition, a manual review of the reference lists of these articles was conducted, leading to the identification of 27 further potentially relevant studies. However, after applying the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, only 15 studies met all eligibility requirements and were included in the final meta-analysis. These 15 studies provide quantitative data on the relationship between ASD and FQoL, allowing for a comprehensive statistical synthesis. The complete article selection process is illustrated in Figure 1. Data Extraction and Measurement Data were extracted independently by two co-authors. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion or adjudication by a third reviewer. To assess the risk of bias beyond the funnel plot asymmetry analysis, we reviewed the methodological quality of each included study based on selection criteria, measurement tools, reporting completeness, and statistical rigour. However, no formal risk of bias tool (e.g., Cochrane’s risk of bias) was applied, due to the observational nature of most studies. Statistical Analysis All statistical analyses were conducted using the Jamovi Project software to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Effect sizes were calculated during the meta-analysis. Specifically, for each study, standardised mean differences (SMD) were computed to quantify the relationship between ASD and QoLF. These effect sizes were derived from the data provided in the selected studies and then pooled using a random-effects model. This model was chosen to account for the expected variability between studies and to provide a more accurate estimate of the overall effect. The calculation of effect sizes in this manner allowed for a comprehensive statistical analysis and integration of the data, ensuring consistency and comparability across the included studies. Associations Between Symptom Severity, Age, and FQoL Heterogeneity and Publication Bias Several statistical measures were applied to assess the heterogeneity and validity of the results obtained. First, the estimate of τ2 , which represents the true variance between the effects of the studies, beyond the variance attributable to chance, was .12, indicating considerable heterogeneity between the studies analysed. This value suggests that the observed differences between studies cannot be explained by sampling error alone. The Cochran’s Q-test was conducted to assess whether the variability in study results exceeded that expected by chance. A significant Q value (p < .0001) confirmed that the heterogeneity among studies was real and not attributable to random variation. These results highlight the presence of substantial variability in the estimated effects across studies. The I² statistic, which quantifies the percentage of total variation across studies attributable to true heterogeneity rather than sampling error, was 91.23%. This high value reinforces the conclusion that nearly all observed variability stems from heterogeneous study characteristics. A prediction interval was also calculated to predict the range within which true effects are likely to lie in future studies. In this case, the interval ranged from -.64 to .81, suggesting that some studies may show negative effects, while others may show positive effects, highlighting the wide variability in results. To identify possible outliers or influential studies, we used the studentized residuals and Cook’s distances. None of the studies were identified as outliers or influential, indicating that all included studies contribute in a balanced way to the overall results of the model. Finally, tests of funnel plot asymmetry provided mixed indications. The regression test indicated the presence of skewness in the plot (p = .02), which could suggest the existence of publication bias or the influence of other distorting factors. However, the rank correlation test was not significant, which leaves open the possibility that the observed skewness is not conclusive but does merit a cautious interpretation of possible biases in the data. Studies Overview Fifteen studies were included in this meta-analysis, providing point estimates of effect sizes (ESs) for two key variables: child age and symptom severity in the context of ASD and their impact on FQoL. Ten studies (Alhazmi et al., 2018; Borilli et al., 2022; Derguy et al., 2018; Faden et al., 2023; Garrido et al., 2021; Higgins et al., 2023; Hsiao, 2013; Moretto et al., 2020; Romaniuk et al., 2022; Vaz et al., 2021) examined the relationship between child age and QoL, while eleven studies (Borilli et al., 2022; Faden et al., 2023; Garrido et al., 2020; Garrido & Carballo, 2015; Higgins et al., 2023; Ismail et al., 2022; Moretto et al., 2020; Papadopoulos et al., 2023; Romaniuk et al., 2022; Rutherford et al., 2023; Smith et al., 2021) addressed ASD symptom severity and QoL. Descriptive details are presented in Table 1, while additional descriptive information is provided in Table 2. Child Age and QoL For analyses examining the correlation between child age and QoL (k = 10 studies), the observed Fisher r-to-z transformed correlation coefficients ranged from -.13 to .25, with 89% of estimates being positive. The estimated average Fisher r-to-z correlation coefficient, based on the random effects model, was = .10 (95% CI [.01, .20]), with statistical significance (z = 2.09, p = .03). According to the Q-test, the true results were heterogeneous, Q(8) = 19.18, p = .01, τ² = .012, I² = 56.88%, and a 95% prediction interval for the true results ranged from -.13 to .35. Thus, while the average correlation was positive, individual studies may report negative findings. Examination of studentised residuals revealed no outliers (values did not exceed ± 2.77). Cook’s distances indicated that no study was overly influential. Both the rank correlation test and regression test showed no evidence of funnel plot asymmetry (p = .61 and p = .06, respectively). The funnel plot is depicted in Figure 2, confirming symmetry. Symptom Severity and QoL For analyses of symptom severity and QoL (k = 11 studies), Fisher r-to-z transformed correlation coefficients ranged from -.35 to .66, with positive estimates predominating (56%). The estimated average correlation coefficient was = .08 (95% CI [-.15, .32]), which was not statistically significant (z = .67, p = .50). The Q-test indicated high heterogeneity, Q(8) = 77.49, p < .0001, τ² = 0.12, I² = 91.23%, with a 95% prediction interval ranging from -.64 to .81. This suggests that while the average correlation was positive, a significant proportion of individual studies could report negative correlations. No outliers were detected based on studentised residuals (± 2.77 threshold), and Cook’s distances indicated no overly influential studies. However, asymmetry in the funnel plot was observed in the regression test (p = .02), though not in the rank correlation test (p = .25), suggesting a potential publication bias. Figure 3 presents the funnel plot, illustrating asymmetry. Figure 3 Forest Plot of the Relationship between Severity of Infant Impairment and Family Quality of Life.   Heterogeneity and Bias The meta-analysis revealed varying levels of heterogeneity across the included studies. In the analysis of child age and QoL, heterogeneity was moderate (τ² = .012, I² = 56.88%), whereas symptom severity and QoL exhibited high heterogeneity (τ² = .12, I² = 91.23%). Prediction intervals for both analyses indicated that true results could vary widely, with some studies reporting negative correlations. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plot asymmetry tests. While the rank correlation test was non-significant in both analyses, the regression test suggested potential bias in the symptom severity analysis. Despite these findings, the overall results consistently suggest a small but significant positive average correlation between child age and family QoL ( = .10). 2) and a non-significant positive trend for symptom severity and QoL ( = .08). Table 1 provides a detailed account of the Fisher r-to-z transformed correlation coefficients for each study, ranging from −.35 to .66, with positive estimates predominating. Q-tests for heterogeneity and I² statistics are also reported, demonstrating moderate to high variability. Figures 3 and 4 display influence diagnostics, including plots of studentized residuals and Cook’s distances. No studies exceeded the thresholds for outliers or undue influence, ensuring the robustness of the results. This meta-analysis provides a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing family quality of life (FQoL) in the context of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). By synthesising previous research, it quantifies the influence of two key clinical characteristics—child age and symptom severity—on FQoL. Child Age and Family Quality of Life: A Small but Positive Association The analysis revealed a small but positive association between child age and FQoL, with moderate heterogeneity. This finding aligns with prior studies that observed an increase in FQoL as children with ASD grow older (Dykens, 2015; Lecavalier & Schwartz, 2009; Maenner et al., 2020). One possible explanation is that age functions as a proxy for time since diagnosis, which is typically a period of high emotional distress for families (Perry et al., 2016). Over time, families may undergo a process of emotional adaptation and benefit from more sustained engagement with support services. Additionally, older children may have had more opportunity to access and benefit from interventions, even though duration of treatment was not directly measured in the included studies. The fact that all included studies involved children receiving some form of intervention further supports this interpretation. Six studies explicitly mentioned the use of therapeutic approaches (Alhazmi et al., 2018; Derguy et al., 2018; Faden et al., 2023; Papadopoulos et al., 2023; Rutherford et al., 2023; Smith et al., 2021), while others recruited participants from clinical or specialised ASD services (Borilli et al., 2022; Higgins et al., 2023; Ismail et al., 2022; Romaniuk et al., 2022; Vaz et al., 2021). Future research should examine whether time since diagnosis or length of intervention mediates this relationship, as well as the specific treatment components that promote sustained improvements in FQoL. Symptom Severity and Family Quality of Life: A Non-Significant Association The relationship between symptom severity and FQoL was found to be negative but not statistically significant, with high heterogeneity and indications of publication bias. This result is consistent with prior studies reporting mixed findings regarding the effect of ASD symptom severity on family functioning (Smith et al., 2020; Widyawati et al., 2021). While symptom intensity may represent a potential stressor, the data suggest that it does not directly determine family outcomes. One plausible interpretation is that FQoL is best understood within broader theoretical frameworks that account for family adaptation to stressors. Models such as ABCX (Hill, 1949) and Double ABCX (McCubbin & Patterson, 1983) have been proposed by several included studies (Higgins et al., 2023; Ismail et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2021) as suitable frameworks to explain these dynamics. These models conceptualise FQoL as one dimension of the family’s adjustment to chronic challenges, shaped by access to resources, family resilience, and coping strategies, rather than by symptom severity alone. Moreover, some studies point to the importance of treatment-related variables in moderating the impact of severity. For instance, Rutherford et al. (2023) demonstrated that practical interventions such as visual supports improved communication and reduced caregiving burden, leading to increased FQoL. In contrast, Moretto et al. (2020) found no differences in FQoL between mothers of verbal and non-verbal children, reinforcing the idea that symptom expression alone may not determine FQoL. Additionally, factors such as financial stability and parental resilience have been identified as relevant (Hsiao et al., 2013; Garrido et al., 2021), not because they directly predict FQoL, but because they influence how families engage with support systems (Ismail et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2019). This suggests that the focus should shift from child symptomatology to the contextual and systemic variables that support family functioning. Limitations This meta-analysis has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the heterogeneity of the included studies, particularly in terms of methodologies and measures of FQoL, may limit the generalisability of the findings. The small number of studies and variability in sample characteristics further constrain the robustness of the conclusions. Additionally, evidence of potential publication bias, as indicated by the funnel plot, and the presence of high heterogeneity among effect sizes are notable concerns. Future research should address these limitations by including larger and more diverse samples, employing standardised measures of FQoL, and conducting longitudinal studies to capture the evolution of FQoL over time. The modest effect sizes observed also underscore the need for cautious interpretation of the findings. Implications for Future Research Future research should aim to explore in greater depth the moderators that shape the relationship between child characteristics and FQoL. In particular, variables such as access to services, caregiver resources, and family resilience may help explain the inconsistencies observed across studies. Identifying these moderators is essential for understanding why some families adapt better than others in the face of similar levels of severity or developmental needs. Moreover, theoretical frameworks such as the ABCX model (Hill, 1949) and the Double ABCX model (McCubbin & Patterson, 1983) offer valuable lenses for interpreting how families respond to the stressors associated with raising a child with ASD. Future studies should consider applying or empirically testing these models to examine the processes of family adaptation, coping, and the influence of contextual factors on FQoL. In addition, cultural and contextual differences should be examined, as these were not directly tested in this meta-analysis. Tailoring support systems to specific sociocultural contexts may improve outcomes and equity in service provision. Given the small but significant positive association between child age and FQoL, future research should also investigate how support programmes can be adapted to meet age-specific needs. For example, families with younger children may benefit more from early intervention and parent training, while those with older children may require support with transition planning, autonomy development, and access to adult services. Finally, more attention should be directed toward families of individuals with profound autism or higher levels of symptom severity. These groups often face compounded challenges that are insufficiently addressed in current research. Designing flexible and scalable psychosocial interventions that are adaptable across different settings and levels of need is critical to advancing inclusive family support strategies (Lord et al., 2024). The results of this meta-analysis indicate that the relationship between child characteristics—namely age and symptom severity—and FQoL is modest and complex. These findings suggest that child-related factors alone do not fully explain differences in family outcomes. Instead, they should be considered within a broader, dynamic framework that includes treatment-related variables and family adaptation processes. The small but positive association between child age and FQoL may reflect not only developmental progress but also increased time since diagnosis and prolonged exposure to interventions. Similarly, the non-significant association between symptom severity and FQoL may imply that external supports—such as access to services, family coping mechanisms, or social support—play a buffering role in the impact of symptom expression. Accordingly, future research should prioritise examining treatment characteristics, family resources, and systemic supports, rather than focusing exclusively on the child’s clinical profile. Testing theoretical models such as the ABCX and Double ABCX frameworks may enhance our understanding of how families adapt to the ongoing demands of raising a child with ASD and inform the design of more responsive, family-centred interventions. - The study highlights that age serves as a modulating factor in the quality of life, suggesting that parental experience and adaptation over time are crucial for enhancing family well-being. This dynamic is key to the development of family-centred interventions that promote greater emotional and social well-being. - One of the most novel contributions of this work is the integration of psychosocial factors into interventions aimed at families of children with ASD. By recognising the importance of family adaptation throughout the life cycle, the study paves the way for new therapeutic strategies that take into account the emotional impact on parents over time. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Muiño, A., Arrillaga, A., & Corradi, G. (2026). Meta-analysis on family quality of life in autism spectrum disorder. Clinical and Health, 37, Article e260715. https://doi.org/10.5093/clh2026a1 References |

Cite this article as: Muiño, A., Corradi, G., & Arrillaga, A. (2026). Meta-Analysis on Family Quality of Life in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Clinical and Health, 37, Article e260715. https://doi.org/10.5093/clh2026a1

Correspondence: ana.muino@villanueva.edu (A. Muiño).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS