Latent Profile Analyses of Generalized Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Primary Care Patients

[Análisis de los perfiles latentes de los sĂntomas de ansiedad generalizada y depresiĂłn en pacientes de atenciĂłn primaria]

Maider Prieto-Vila1, 2, César González-Blanch3, 4, Rob Saunders5, Joshua E. J. Buckman5, 6, Gabriel Esteller-Collado1, María Carpallo-González7, Juan A. Moriana8, 9, 10, Paloma Ruiz-Rodríguez11, Roger Muñoz-Navarro1, & Antonio Cano-Vindel2

1Department of Personality, Evaluation, and Psychological Treatment, Faculty of Psychology, University of Valencia, Spain; 2Department of Experimental Psychology, Cognitive Processes and Speech Therapy, Faculty of Psychology, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain; 3”Marqués de Valdecilla” University Hospital – IDIVAL, Santander, Spain; 4Department of Psychology, International University of La Rioja (UNIR), Logroño, Spain; 5CORE Data Lab, Centre for Outcomes and Research Effectiveness, Research Department of Clinical, Educational and Health Psychology, University College London, United Kingdom; 6iCope – Camden and Islington Psychological Therapies Services, Camden & Islington NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom; 7Department of Psychology, Universidad Europea de Madrid, Spain; 8Department of Psychology, University of Córdoba, Spain; 9Maimonides Institute for Biomedical Research of Cordoba (IMIBIC), Spain; 10Reina Sofia University Hospital, Cordoba, Spain; 11Madrid Health Service, Tres Cantos, Madrid, Spain.

https://doi.org/10.5093/clh2026a2

Received 2 December 2024, Accepted 27 May 2025

Abstract

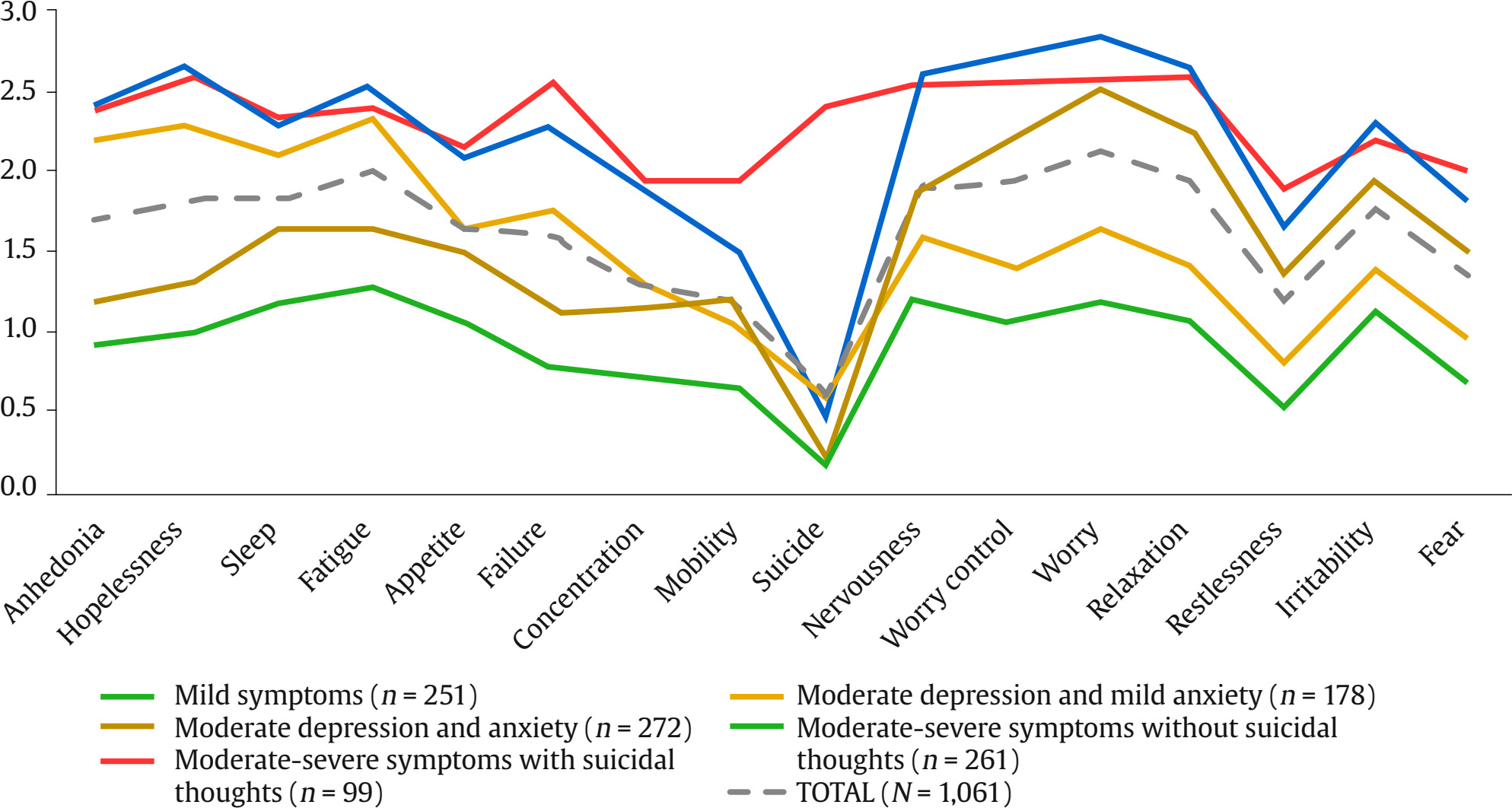

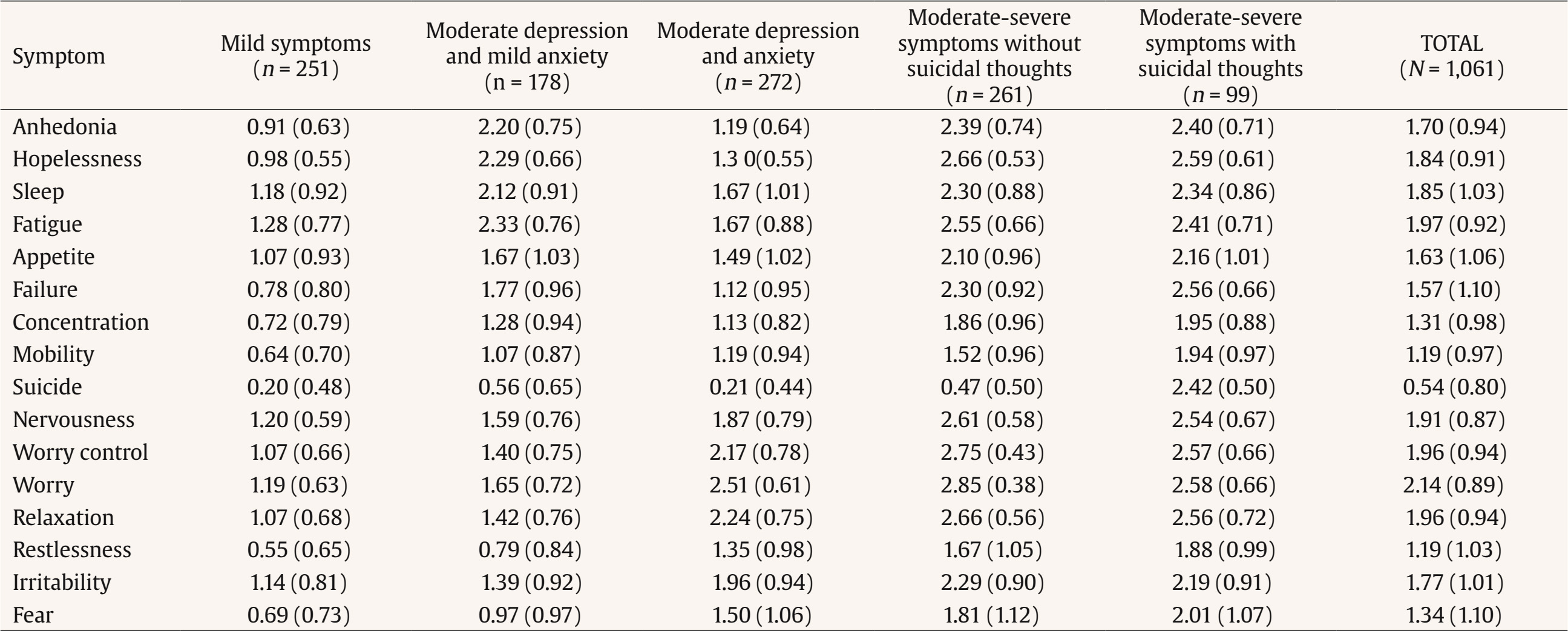

Background: Despite their frequent comorbidity of depression and anxiety, previous studies have focused on their co-occurrence without considering symptomatic heterogeneity across patients. We aimed to identify distinct profiles of anxious-depressive symptoms and associated characteristics. Method: Participants were 1,061 patients from the PsicAP clinical trial. Latent Profile Analysis was used to identify distinct subgroups of patients, and multinomial logistic regression models examined associations person-related characteristics. Results: Five distinct symptomatic profiles were identified: 1) mild symptoms (23.66%); 2) moderate depression and mild anxiety symptoms (16.78%); 3) moderate depression and anxiety symptoms (25.64%); 4) moderate-severe symptoms without suicidal thoughts (24.59%); and 5) moderate-severe symptoms with suicidal thoughts (9.33%). Regression analyses showed that higher scores in somatization, disability, emotional suppression, rumination, and metacognitive beliefs, as well as lower quality of life and social support, were significantly associated with more severe profiles. Conclusions: Considering symptomatic heterogeneity in primary care is important for personalizing treatments based on individual profiles. This approach may optimize healthcare resources by offering tailored care.

Resumen

Antecedentes: A pesar de la frecuente comorbilidad entre la depresión y la ansiedad, los estudios previos se han centrado en su coocurrencia sin considerar la heterogeneidad sintomatológica entre los pacientes. El objetivo de este estudio ha sido identificar diferentes perfiles de síntomas ansioso-depresivos y sus variables asociadas. Método: Participaron 1,061 pacientes del ensayo clínico PsicAP, aplicándose un análisis de perfiles latentes para identificar subgrupos sintomatológicos diferenciados. Se utilizaron modelos de regresión logística multinomial para explorar las variables asociadas. Resultados: Se identificaron cinco perfiles sintomatológicos distintos: 1) síntomas leves (23.66%); 2) síntomas de depresión moderada y ansiedad leve (16.78%); 3) síntomas moderados de depresión y ansiedad (25.64%); 4) síntomas moderado-severos sin ideación suicida (24.59%); 5) síntomas moderado-severos con ideación suicida (9.33%). Los análisis de regresión muestran que puntuaciones más altas en somatización, discapacidad, supresión emocional, rumiación y creencias metacognitivas, así como una menor calidad de vida y apoyo social, se asocian significativamente con perfiles más graves. Conclusiones: Considerar la heterogeneidad sintomática en atención primaria es fundamental para personalizar los tratamientos en función de las características individuales. Este enfoque puede ayudar a optimizar los recursos sanitarios ofreciendo una atención más personalizada a las necesidades del paciente.

Palabras clave

Análisis de perfiles latentes, Tratamientos personalizados, Atención primaria, Ansiedad, DepresiónKeywords

Latent profile analysis, Personalized treatments, Primary care, Anxiety, DepressionCite this article as: Prieto-Vila, M., González-Blanch, C., Saunders, R., Buckman, J. E. J., Esteller-Collado, G., Carpallo-González, M., Moriana, J. A., Ruiz-Rodríguez, P., Muñoz-Navarro, R., & Cano-Vindel, A. (2026). Latent Profile Analyses of Generalized Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Primary Care Patients. Clinical and Health, 37, Article e260716. https://doi.org/10.5093/clh2026a2

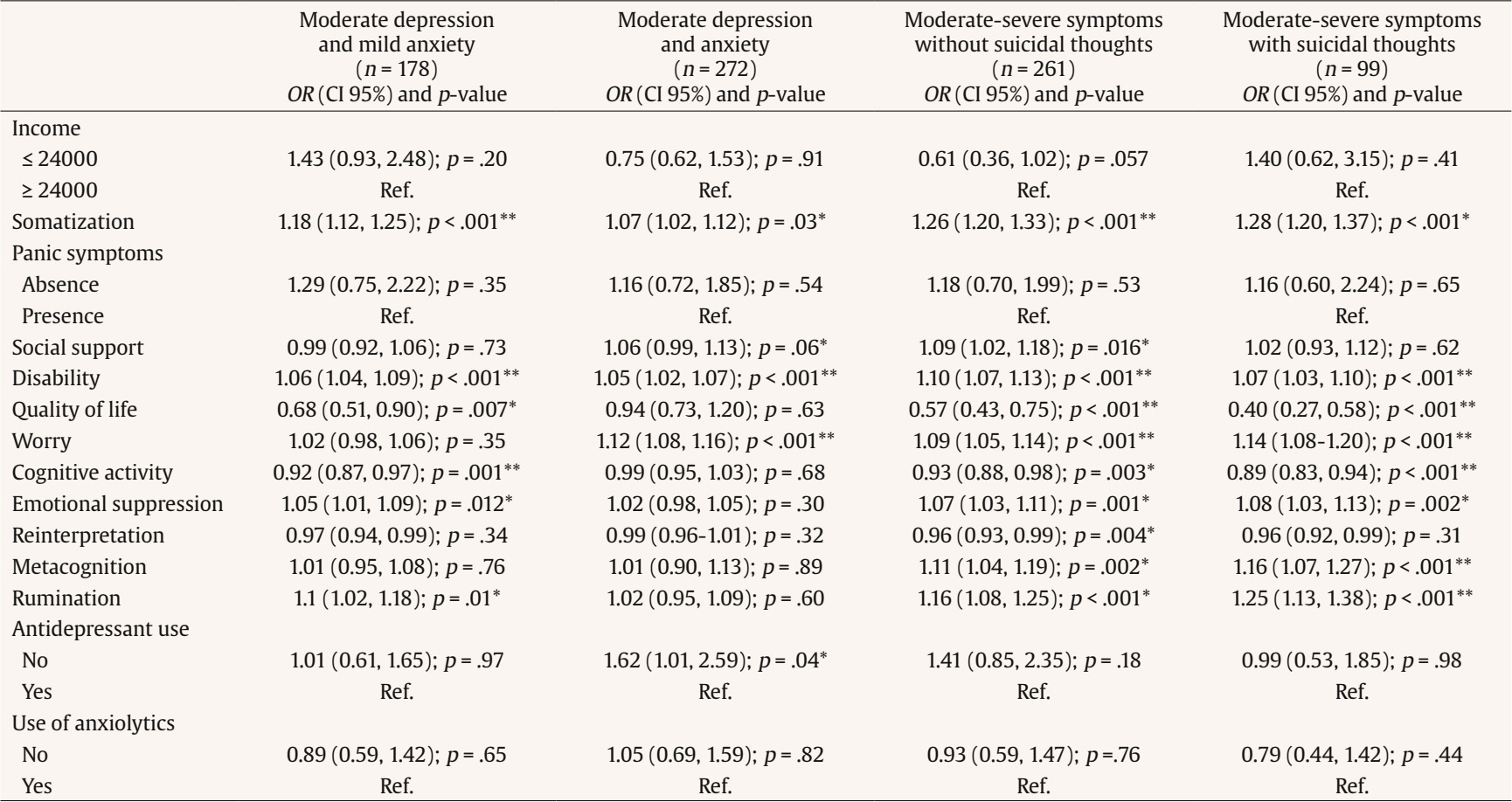

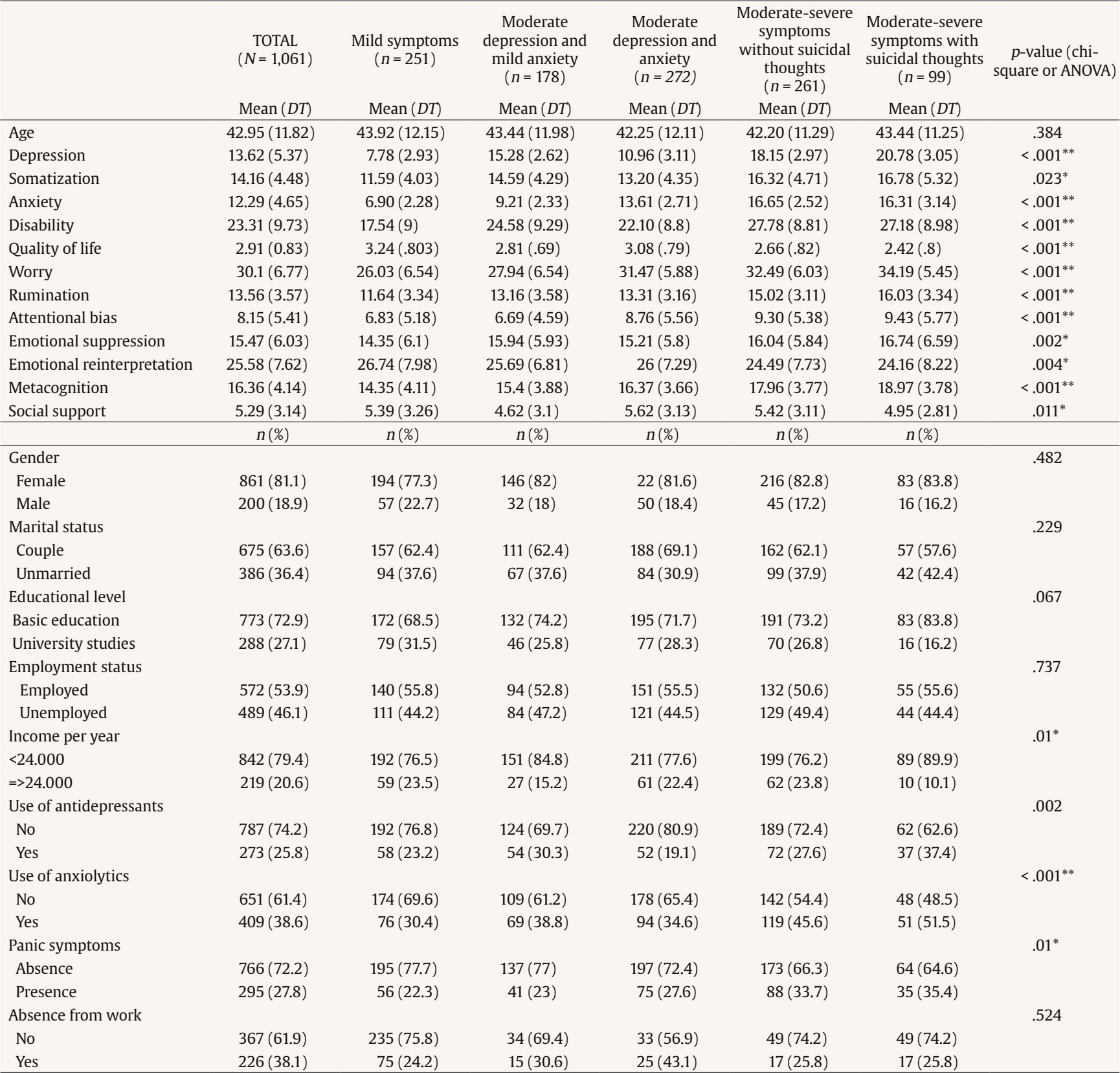

Correspondence: maider.prieto@uv.es (M. Prieto-Vila).According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2022), depression and anxiety are the most prevalent mental disorders worldwide, affecting more than 374 million and 246 million people, respectively. Both emotional disorders have a significant impact on quality of life and daily functioning, causing substantial disability (GBD, 2022) and a significant economic burden for society through healthcare spending (König et al., 2019). Anxiety and depression are frequently encountered in primary care consultations (Finley et al., 2018). Although a variety of evidence-based treatments are clinically recommended (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE, 2022]), many individuals either go untreated or face barriers in accessing these interventions (Moitra et al., 2022). As a result, incorporating evidence-based treatments into primary care has emerged as a key focus in healthcare initiatives worldwide (Patel et al., 2018). It is common to observe high comorbidity between anxiety and depression symptoms, with studies indicating that approximately 60% of individuals with depression also experience generalized anxiety disorder (Johansson et al., 2013; Ruscio et al., 2017). The prognosis of patients with both conditions increases the likelihood of chronicity (Ter Meulen et al., 2021) and suicide risk (Wiebenga et al., 2021). However, most studies focus on co-occurrence based only on diagnostic criteria or on the scales’ cut-off scores, and whilst these approaches are beneficial in screening and communication, it is important to underline their limitations. Diagnostic criteria do not consider the heterogeneity across symptoms and the low specify of diagnosis criteria. For example, in DSM-5 it is possible to obtain 277 depressive diagnostic profiles considering the 9 symptoms of the DSM (Fried et al., 2020). This highlights the need for approaches that go beyond categorical diagnoses to account for the heterogeneity and complexity of symptom presentations. Latent class and profile analyses (LCA/LPA) not only allow for empirical identification of naturally occurring symptom profiles but can also serve to test and refine theoretical models of psychopathology. For instance, these methods can provide empirical support for frameworks such as the tripartite model (Clark & Watson, 1991), transdiagnostic models of emotional disorders (Barlow et al., 2004), or behavioral analytic approaches (Hayes et al., 2013), by identifying patterns of co-occurrence that align with proposed underlying processes. Therefore, the utility of LCA/LPA extends beyond classification: it also offers a means to bridge data-driven findings and psychological theory. Given this theoretical potential, person-centered approaches such as LCA and latent LPA have become increasingly popular in health, behavioral, and social sciences to identify subgroups of individuals based on similar response patterns. LCA employs categorical variables and LPA is an extension of LCA that uses continuous variables (Nylund et al., 2007). Several studies have identified subgroups with different anxiety and depression symptom patterns and their associated characteristics. For instance, Brattmyr et al. (2023) examined outpatients with emotional problems and identified three latent class: somatic anxiety and depression (33%), associated with older age, being single, sick leave, and higher comorbidity; general anxiety and depression (40%), and cognitive symptoms of depression (27%) linked to greater service use. Hou & Zhang (2023) found three profiles in older adults living alone: mild symptoms (30.4%), moderate-mild symptoms (55.3%), and high symptoms (14.4%), with higher depression linked to anxiety, lack of exercise, low social interaction, and impaired functioning, and lower symptoms linked to better self-rated health and life satisfaction. Weiss et al. (2021) found three profiles in women in the general population: asymptomatic (48%), elevated symptoms (16%), and somatic symptoms (36%), with financial security and social support distinguishing the asymptomatic group. Singham et al. (2022) identified five profiles in a sample over 50 years old in general population: 1) high depression and anxiety symptoms (9.7%); 2) sleep difficulties (27%); 3) sleep difficulties and worry (13.4%); 4) sleep difficulties and anhedonia (9.3%); and; 5) asymptomatic individuals (40.5%), finding that profiles marked by sleep problems and depression predicted cognitive decline over time. Therefore, these findings underscore the variability in symptom presentation and associated characteristics. Nevertheless, such analyses have rarely been applied in primary care to identify subgroups of patients with similar anxiety-depressive symptomatology, and knowledge remains limited regarding cognitive-emotional processes, which play a crucial role according to transdiagnostic models. This knowledge potentially could help to adapt the treatments in primary care optimizing the resources. The aims of this study are to: 1) identify subgroups of patients with similar anxiety-depression symptom patterns using LPA in primary care and 2) determine person-related characteristics associated with a higher likelihood of exhibiting different symptom patterns, providing pioneering insights in this area (i.e., cognitive-emotional domains or quality of life). Participants This study consists of 1,061 primary care patients who were randomized in the original study (Cano-Vindel et al., 2021). The patients were selected from 22 health centers across 9 autonomous communities in Spain and met the following inclusion criteria: 1) aged between 18 and 65 years and 2) exceeding the cutoff point on any of the scales used to assess depressive, anxious, or somatoform symptoms (PHQ-9 ≥ 10, GAD-7 ≥ 10, PHQ-15 ≥ 5, respectively). Patients were excluded if they showed: 1) severe depressive symptoms (PHQ ≥ 24); 2) high levels of disability (SDS ≥ 26); 3) recent suicidal behavior; 4) that they were already receiving psychological treatment; 5) difficulties in understanding Spanish; or 6) a diagnosis of substance use disorder or severe mental illness (e.g., personality disorder, severe eating disorder, bipolar disorder, or psychotic disorder). These patients were interviewed using the SCID-I interview (First et al., 1999) by a clinical psychologist involved in the PsicAP project to confirm the presence of exclusion criteria (Muñoz-Navarro, Cano-Vindel, Medrano, et al., 2017; Muñoz-Navarro, Cano-Vindel, Moriana, et al., 2017). In such cases, the patient was excluded from the clinical trial and referred to the general practitioner (GP) for the most appropriate treatment or referral to a suitable service. These exclusion criteria followed the recommendations of the original trial protocol, which was aligned with the stepped-care model of mental health care in Spain, where patients with mild to moderate symptoms are treated in primary care and more severe or complex cases are referred to specialized services (Cano-Vindel et al., 2016; González-Blanch et al., 2018). Procedure The PsicAP clinical trial was evaluated and approved by the National Ethics Committee and the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (code: ISRCTN58437086) in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and complied with the Spanish Data Protection Law (EUDRACT: 2013-001.955-11). The procedure for patient participation included four phases: recruitment, evaluation, treatment, and follow-up. Patient recruitment was carried out exclusively in the primary care setting. On one hand, GPs, upon detecting patients with potential emotional disorders (depression, anxiety, or somatization), referred them to the psychologist-researcher for a pretreatment evaluation. On the other hand, the psychologist-researchers used the PHQ-4 screening tool (Cano-Vindel et al., 2018) to invite patients at the primary care center to complete the questionnaire in waiting areas. If the screening result was positive, patients were invited to a pretreatment evaluation to determine if they met the inclusion criteria. Before the pretreatment evaluation, all study participants were informed about the details of the trial by the PCP or the psychologist-researcher, provided with written information, and signed informed consent. Patients meeting the inclusion criteria were randomized to the control or experimental group (1:1). Patients in the control group received treatment as usual (TAU) in primary care, informal counselling, and/or psychotropic prescription by the GP, while patients in the experimental group received TAU plus seven sessions of transdiagnostic group cognitive-behavioral treatment (TDG-CBT). Post-treatment and follow-up evaluations were conducted at 3, 6, and 12 months by the psychologist-researcher (see more in Cano-Vindel et al., 2016). Instruments Sociodemographic and Psychotropic Drug Use Sociodemographic data (gender [male/female], age, marital status, education level, and employment status), and psychotropic drug use (antidepressants and anxiolytics) were collected using ad hoc-designed questionnaires. Except for age, these variables were dichotomized as follows: marital status (with partner vs. without partner), education level (non-university vs. university studies), employment status (employed vs. unemployed), antidepressant use (yes vs. no), and anxiolytic use (yes vs. no). Depressive, Anxious, and Somatic Symptoms Depressive Symptoms. Symptoms were measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) validated in the Spanish population (Muñoz-Navarro, Cano-Vindel, Medrano, et al., 2017). Scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms: 5-9 = mild, 10-14 = moderate, 15-19 = moderate-severe, and 20-27 = severe. In this study, internal consistency was acceptable (α = .75). Generalized Anxiety Symptoms. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire (GAD-7) (Muñoz-Navarro, Cano-Vindel, Moriana, et al., 2017) consists of 7 items based on DSM-IV criteria for generalized anxiety disorder. Scores range from 0 to 21, with 5-9 indicating mild anxiety, 10-14 moderate anxiety, and 15 or more severe anxiety. In this study, internal consistency was acceptable (α = .79). Somatic Symptoms. The Patient Health Questionnaire-Somatization module (PHQ-15) (Montalban et al., 2010) consists of 15 items scored on a Likert scale from 0 (not bothered) to 2 (bothered a lot). Scores range from 0 to 30, with 5 or more indicating somatoform symptoms, 10 or more moderate somatization, and 15 or more severe somatization. Internal consistency in this study was acceptable (α = .70). Symptoms of Panic Disorder. The Patient Health Questionnaire-Panic Disorder module (PHQ-PD) (Muñoz-Navarro et al., 2016) is a 15-item dichotomous (yes/no) questionnaire used to screen for the presence of panic disorder based on DSM-IV criteria. A positive screening requires an affirmative response to the first item, at least one endorsement among the following three items, and four or more somatic symptoms. Cognitive-Emotional Processes Worry. The Penn State Worry Questionnaire-Abbreviated (PSWQ-A) (Muñoz-Navarro et al., 2021) measures pathological worry with 8 items scored on a Likert scale from 1 (not typical) to 5 (very typical). Higher scores indicate more pathological worry. In this study the internal consistency was good (α = .89). Rumination (Brooding). The Brooding subscale of the Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS-B) (Muñoz-Navarro et al., 2021) assesses self-reproach with 5 items on a Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). Higher scores indicate greater brooding. In this study the internal consistency was good (α = .78). Emotional Regulation. The Emotional Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) (Cabello et al., 2013). It is a 10-item scale with two subscales: adaptative (ERQ-R, cognitive reappraisal) and maladaptive (ERQ-S, expressive suppression) strategies. Responses are given by a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Internal consistency in this study was good (α = .77). Negative Metacognitive Beliefs. The Metacognitive Beliefs Questionnaire-Negative Beliefs subscale (MCQ-NB) (Muñoz-Navarro et al., 2021) consists of 5 items measuring beliefs about uncontrollability and danger of thoughts. The internal consistency was acceptable (α = .77). Attentional and Cognitive Biases. The Inventory of Cognitive Activity in Anxiety Disorders–Panic Brief version (IACTA-PB) (Muñoz-Navarro et al., 2021) consist of a 5-item scale to measure attentional and cognitive biases by a Likert scale from 0 (almost never) to 4 (almost always) with maximum punctuation of 20. The internal consistency in this study was good (α = .83). Measures of Quality of Life and Disability Quality of Life. The WHOQOL-BREF (Lucas-Carrasco, 2012) is a 26-item questionnaire that assesses quality of life in four domains: physical, psychological, environmental, and social relationships. Internal consistency in this study was good (α = .86). Disability. The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) (Luciano et al., 2010) evaluates disability across five daily domains (work, social, family functioning, stress, and perceived social support). Internal consistency in this study was acceptable (α = .71). Data Analysis Analysis of Anxious-Depressive Symptom Profiles In this study, we included in the LPA the individual item scores from the depression (PHQ-9) and generalized anxiety (GAD-7) questionnaires. A number of model fit statistics were used to determine the optimal profile solution: Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test (VLMR-LRT), where a p-value < .05 indicates that model k fits the data better than model k-1; Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and sample size adjusted BIC (SABIC), where the lowest value among models suggests better fit (Vrieze, 2012). The entropy value of each model, which ranges from 0 to 1, and indicates the accuracy of classification into latent profiles, a value ≥ .80 indicates high accuracy (where at least 80% of individuals are correctly classified into latent profiles, values between .80 and .40 indicate medium accuracy, and ≤ .40 indicates low accuracy) (Clark & Muthén, 2009). To determine the optimal number of profiles (or subgroups), each model (k) was compared with the previous model (k-1) using the described model fit statistics. Since there was no hypothesis as to the number of profiles to be identified, the analysis started with a 2- profile model, and increased the number of classes until the VLMR-LRT became non-significant, which is one of the options to select the optimal number of profiles (Lo et al., 2001). Mplus software version 8.7 was used to perform the LPA (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Association between Person-related Characteristics and Anxious-Depressive Symptom Profiles Associations between measured baseline variables (see Table 1 for the full list of variables) and profile membership were tested using multinomial logistic regression, after identifying five profiles. These variables included sociodemographic characteristics, cognitive-emotional processes, and measures of quality of life and disability, as described in the Instruments section. Only variables with p-values below .05 in univariable analyses (ANOVA and t-test for continuous variables, and chi-square test for categorical variables) were entered into the multivariable models. To avoid collinearity issues, the total scores from the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were excluded, as LPA was conducted using individual items from both questionnaires. These analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27 (IBM Corp., 2020). Descriptive Statistics The average age of the participants was 42.9 years (SD = 11.82), 81.1% being women. Of the total sample, 27.1% reported a university degree or higher, 53.9% reported they were employed, and 63.4% indicated they had a partner. Regarding psychotropic drug use, 25.8% were taking antidepressants, and 38.6% were using anxiolytics. In terms of clinical variables, participants exhibited moderate depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 = 13.62, SD = 5.37), moderate somatic symptom severity (PHQ-15 = 14.16, SD = 4.48), moderate generalized anxiety symptoms (GAD-7 = 12.29, SD = 4.65), and 27.3% showed possible panic disorder, according to the PHQ-PD questionnaire. Patients had an average score of 30.1 (SD = 6.77, range = 8-40) on the PSWQ-A; 13.56 (SD = 3.57, range = 0-20) on the RRS-B; and an average score of 8.15 (SD = 5.41, range = 0-20) on the IACTA-PB. Regarding the two subscales of the ERQ, patients showed an average score of 15.47 (SD = 6.03, range = 4-24) for ERQ-S, which is considered a maladaptive emotional regulation strategy, and an average score of 25.35 (SD = 15.47, range = 6-42) ERQ-R, an adaptive emotional regulation strategy. Lastly, the average score was 16.36 (SD = 4.14, range = 5-20) on MCQ-NB. Regarding disability, patients had an average score of 23.31 (SD = 9.73, range = 0-50) on the SDS and an average score of 2.91 (SD = 0.83, range = 1-5) for quality of life, as assessed by the WHOQOL-BREF. See Table 1 for more details. Latent Profile Analysis The Five-profile model was selected as the optimal solution, providing the best fit to the data. The VLMR-LRT test reported a p-value higher than .05 for the six-profile model, indicating that the Five-profile model fit the data better. Furthermore, the entropy value was the highest in the Five-profile model (.853), suggesting better levels of classification accuracy compared to other models (see Table 2). Table 2 Latent Profile Analysis Fit Indices for a One- to Six-Profile Solution for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 Item Scores   The profiles are described as follows: 1) mild symptoms (n = 251, 23.66%), characterized by low levels across most symptoms (average score between 0 and 1.2), with the highest scores in sleep disturbances, fatigue, excessive worry, and irritability; 2) moderate depression and mild anxiety (n = 178, 16.78%): members of this profile demonstrate mild anxiety symptoms on average, but report moderate depression symptom levels with symptoms of anhedonia, hopelessness, sleep disturbance and fatigue scored particularly high compared to other symptoms; 3) moderate depression and anxiety (n = 272, 25.64%), characterized by moderate-to-high levels of symptoms, particularly higher scores in anxiety symptoms. Especially excessive worry, inability to control worry, and difficulty for relaxing (scores above 2); 4) moderate-severe symptoms without suicidal thoughts (n = 261, 24.59%), characterized by high levels of symptoms across most domains (scores above 2), with a low average score (0.47) for suicidal or self-harm thoughts; 5) moderate-severe symptoms with suicidal thoughts (n = 99, 9.33%), characterized by high levels of symptoms across most domains (scores above 2), with notable presence of suicidal or self-harm thoughts (2.42 on a scale of 0 to 3). Figure 1 graphically represents the symptomatic distribution of the latent profiles analyses of depressive and anxious symptoms and Table 3 the punctuation of the items on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7. Figure 1 Result of the Distribution of Depression and Anxiety Symptomatology according to Latent Profile Analyses.   Table 3 Description of the Depression and Anxiety Symptoms of the Total Sample and by Latent Profile   Association between Latent Profiles and Person-related Characteristics A multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed to identify associations between clinical, sociodemographic, cognitive-emotional, disability and life quality variables and the latent profile analyses. A mild symptom profile was used as the reference category since it showed the lowest symptom levels compared to the other identified latent profiles. The probability of belonging to the moderate depression and mild anxiety profile (vs. mild symptoms profile) was higher for patients with higher scores in somatic symptoms (OR = 1.18, 95% CI [1.12, 1.25]), disability (OR = 1.06, 95% CI [1.04, 1.09]), emotional suppression (OR = 1.05, 95% CI [1.01, 1.09]), rumination (OR = 1.1, 95% CI [1.02, 1.18]), and lower scores in cognitive activity (OR = 0.92, 95% CI [0.87, 0.97]) and quality of life (OR = 0.68, 95% CI [0.51, 0.90]). The probability of belonging to the moderate depression and anxiety profile (vs. mild symptoms profile) was higher for patients with higher scores in somatic symptoms (OR = 1.07, 95% CI [1.02, 1.12]), social support (OR = 1.06, 95% CI [0.99, 1.13]), disability (OR = 1.05, 95% CI [1.02, 1.07]), worry (OR = 1.02, 95% CI [1.08, 1.16]), and antidepressant use (OR = 1.62, 95% CI [1.01, 2.59]). The probability of belonging to moderate-severe symptoms without suicidal thoughts profile (vs. mild symptoms profile) was higher for patients with higher scores in somatic symptoms (OR = 1.26, 95% CI [1.02, 1.33]), social support (OR = 1.09, 95% CI [1.02, 1.18]), disability (OR = 1.1, 95% CI [1.07, 1.13]), worry (OR = 1.09, 95% CI [1.05, 1.14]), emotional suppression (OR = 1.07, 95% CI [1.03, 1.11]), metacognition (OR = 1.11, 95% CI [1.04, 1.19]), and rumination (OR = 1.02, 95% CI [0.95, 1.09]), and lower scores in cognitive activity (OR = 0.93, 95% CI [0.88, 0.98]) and quality of life (OR = 0.57, 95% CI [0.43, 0.75]). The probability of belonging to moderate-severe symptoms with suicidal thoughts profile (vs. mild symptoms profile was higher for patients with higher scores in somatic symptoms (OR = 1.28, 95% CI [1.2, 1.37]), disability (OR = 1.07, 95% CI [1.03, 1.1]), worry (OR = 1.14, 95% CI [1.08, 1.2]), emotional suppression (OR = 1.08, 95% CI [1.03, 1.13]), metacognition (OR = 1.16, 95% CI [1.07, 1.27]), and rumination (OR = 1.25, 95% CI [1.13, 1.38]), and lower scores in cognitive activity (OR = 0.89, 95% CI [0.83, 0.94]) and quality of life (OR = 0.4, 95% CI [0.27, 0.58]). Main Findings This study identified five profiles of anxious-depressive symptoms through LPA, as well as different person-centered characteristics associated with each profile in 1061 primary care patients. The five identified profiles are characterized by mild symptom profile (23.66%), moderate depression and mild anxiety profile (16.8%), moderate depression and anxiety profile (25.6%), moderate-severe symptoms without suicidal thoughts profile (24.6%), and moderate-severe symptoms with suicidal thought profile (9.3%). Different person-related characteristics were found to be associated with the different profiles such as social support or emotional regulation strategies. The five profiles identified differ in number from different previous mentioned studies, where it is common to detect three symptom profiles characterized by symptom severity: absence (the most prevalent profile), mild-moderate, and severe symptoms (Hou & Zhang, 2023; Weiss et al., 2021). The UK study (Singham et al., 2022) also identified five profiles, but three of them were characterized by sleep difficulties. This difference may be due to the inclusion of older participants, who tend to report more sleep disturbances, and to the absence of screening criteria for emotional disorders in their sample. In contrast, in outpatient samples with emotional difficulties, such as in Brattmyr et al. (2023), fewer profiles were found (three in total), but with clearer differentiation in somatic symptoms and cognitive activity. This supports the idea that when emotional symptoms are present, LPA helps to identify more specific patterns of heterogeneity. Regarding the higher association of patients’ characteristics and identified profiles, as has been seen in previous primary care studies the patients with higher quality of life are associated with mild clinical symptom presentations across the patients (Buckman et al., 2021; Prieto-Vila et al., 2024) as was found also in the current study. It is notable that the moderate depression and mild anxiety profile is the only profile associated with a higher likelihood of antidepressant use compared to the mild symptom profile, even though it is not the most severe symptom profile. However, it stands out for having higher depressive symptom scores on average than anxiety symptoms, unlike the more severe profiles, which show elevated levels of both anxiety and depression. This may influence the GP decision to prescribe antidepressant medication where the anxiety symptoms may mask the severity of depression. As it is shown in Table 4, it is worth noting that multinomial logistic regression results show no significant differences compared to mild symptom profile, and the more severe symptom profiles do have a higher percentage of people taking psychotropic medications based on descriptive statistics. For moderate-severe symptoms without suicidal thoughts profile, the 27.6% use antidepressants and 45.6% use anxiolytics, while for the moderate-severe symptoms with suicidal thoughts profile the 37.6% use antidepressants and 51.5% use anxiolytics. Although not significant across all comparisons, perceived social support helped differentiate the “moderate depression and mild anxiety” and “moderate-severe symptoms with suicidal thoughts” profiles from the mild group. These patterns may reflect more internalized symptoms or greater social isolation, respectively—both clinically relevant in guiding assessment and intervention. Table 4 Multinomial Logistic Regression Results. Reference Category “Mild Symptoms Profile”. OR (CI 95%) and p-value   Maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, such as rumination, emotional suppression, and pathological worry, have been shown to be associated with the onset and maintenance of emotional disorders (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010). Although all profiles were compared against the mild group, maladaptive emotion regulation strategies became increasingly prominent in the more severe symptom profiles, especially in the group marked by suicidal ideation. For example, metacognitive beliefs showed the strongest association with the most severe profiles. Patients within these profiles may benefit from specific intervention components focused on cognitive restructuring or emotional regulation techniques, as compared to those in the mild depressive symptoms profile. Supporting this, recent findings by Muñoz-Navarro et al. (2022) showed that directly targeting these processes led to transdiagnostic improvements in anxiety, depression, and somatic symptoms. Limitations and Strengths Our measures were evaluated using self-reported instruments, which are subject to limitations such as response biases. However, we exclusively employed tools validated for use in primary care settings. Additionally, we conducted validity studies on a subsample of our patients (15% of the total sample), using semi-structured interview, the gold standard, as a benchmark to determine the optimal cut-off score for these measures (Muñoz-Navarro et al., 2016; Muñoz-Navarro, Cano-Vindel, Medrano, et al., 2017; Muñoz-Navarro, Cano-Vindel, Moriana, et al., 2017). We further evaluated the PHQ modules within our primary care sample, confirming excellent psychometric properties, including reliability and construct validity (González-Blanch et al., 2018). This study has notable strengths, including a large sample size (N = 1,061) of primary care patients, which enhances the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, the use of LPA introduces a person-centered approach that identifies distinct symptom profiles, offering insights that support more tailored and effective interventions. However, future studies could include more complete instruments within each domain to better capture clinical nuances and identify more differentiated symptom profiles. Clinical Implications and Future Directions This study highlights the symptomatic heterogeneity of anxiety and depression in primary care patients. It not only highlights the severity index (mild/moderate/severe) but also differences in the symptoms of the latent profiles (i.e., moderate-severe symptoms without suicidal thoughts profile differ from moderate-severe symptoms with suicidal thought profile in the absence of suicidal thoughts) and also related variables for those profiles, for example, in more severe profiles there are more maladaptive emotional regulation strategies, or there is one profile with a high punctuation on suicidal thoughts. This leads us to consider the personalization of group psychological treatments in primary care services. The original study (Cano-Vindel et al., 2021) indicated that adding seven sessions of transdiagnostic group cognitive-behavioral therapy to usual treatment significantly reduces anxiety and depression symptoms at post-treatment evaluation, with benefits maintained at the one-year follow-up. However, we can consider the existence of symptomatic heterogeneity, suggesting that patients likely have different therapeutic needs and may require different types of treatment. Therefore, a future research direction in primary care could involve grouping patients into more homogeneous psychological treatment groups based on the symptoms they present and adjusting treatment components, such as emotion regulation techniques or suicide prevention modules, according to the clinical profile. This study highlights the value of LPA in identifying subgroups of patients with distinct patterns of anxiety and depression symptoms, moving beyond traditional diagnostic approaches based on dichotomous criteria. These profiles reveal significant variability in symptom patterns, emphasizing that emotional disorders cannot be fully captured by a one-size-fits-all diagnostic approach. Our results underscore the need to consider heterogeneity across patients when designing psychological treatments in primary care. Recognizing specific symptom profiles can enhance intervention precision and improve treatment outcomes. Highlights Identification of Symptom Heterogeneity and Latent Profile Characteristics Using Latent Profile Analysis (LPA), this study identifies five distinct profiles of anxiety and depression symptoms among primary care patients: Mild Symptoms, Moderate Depression and Mild Anxiety, Moderate Depression and Anxiety, Moderate-Severe Symptoms without Suicidal Thoughts, and Moderate-Severe Symptoms with Suicidal Thoughts. These findings demonstrate the wide variability of symptomatology, challenging conventional diagnostic approaches and providing a more personalized understanding of emotional disorders. Associations of Clinical and Sociodemographic Characteristics with Symptom Profiles The study identifies significant associations between patient characteristics and symptom profiles. Higher somatic symptoms, disability, and maladaptive emotional regulation strategies (e.g., rumination, worry, emotional suppression) are linked to more severe profiles. In contrast, the mild symptom profile is associated with better quality of life and cognitive activity. Clinical Implications for Personalized Interventions The identification of symptom heterogeneity and associated patient characteristics underscores the need for personalized treatment approaches in primary care. For example, the Moderate-Severe Symptoms with Suicidal Thoughts profile suggests the need for suicide prevention modules, while milder profiles may benefit from interventions targeting emotional regulation and quality of life improvements. Future research should further explore subgroup-specific interventions to address diverse therapeutic needs. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Funding This research was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science (RETOS grant PID2019-107243RB-C21 and FPI grant PRE2020-092381). Cite this article as: Prieto-Vila, M., González-Blanch, C., Saunders, R., Buckman, J. E. J., Esteller-Collado, G., Muñoz-Navarro, R., Moriana, J. A., Ruiz-Rodríguez, P., Carpallo-González, M., & Cano-Vindel, A. (2026). Latent profile analyses of generalized anxiety and depressive symptoms in primary care patients. Clinical and Health, 37, Article e260716. https://doi. org/10.5093/clh2026a2 References |

Cite this article as: Prieto-Vila, M., González-Blanch, C., Saunders, R., Buckman, J. E. J., Esteller-Collado, G., Carpallo-González, M., Moriana, J. A., Ruiz-Rodríguez, P., Muñoz-Navarro, R., & Cano-Vindel, A. (2026). Latent Profile Analyses of Generalized Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Primary Care Patients. Clinical and Health, 37, Article e260716. https://doi.org/10.5093/clh2026a2

Correspondence: maider.prieto@uv.es (M. Prieto-Vila).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS