Trait Mindfulness, Rumination, and Well-being in Family Caregivers of People with Acquired Brain Injury

[Mindfulness como rasgo, la rumiaci├│n y el bienestar en los cuidadores de las personas con da├▒o cerebral adquirido]

Esther Calvete1, Mª Angustias Roldan Franco2, Lucia Oñate1, Macarena Sánchez-Izquierdo Alonso2, and Laura Bermejo-Toro2

1Universidad de Deusto, Bilbao, Spain; 2Universidad Pontificia Comillas, Madrid, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2021a5

Received 27 January 2020, Accepted 15 January 2020

Abstract

This study examined the relationship between trait mindfulness, rumination, quality of life, anxiety, and depression in family caregivers of people with Acquired Brain Injury (ABI). Participants were 78 caregivers (75.6% women) aged between 22 and 80 years. The participants completed measures of behavioral and emotional problems in the person with ABI, trait mindfulness, symptoms of anxiety and depression, quality of life, and rumination. The results showed that mindfulness is associated with fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression and better quality of life, and that this is explained through less use of rumination. Likewise, behavioral and emotional problems of the person with ABI were associated with more depression and lower quality of life in the caregiver. Rumination explained part of this association. Finally, behavioral and emotional problems of the person with ABI were more strongly associated with depression in caregivers with low trait mindfulness.

Resumen

Este estudio examinó la relación entre el rasgo de mindfulness, rumiación, calidad de vida, ansiedad y depresión en cuidadores de personas con daño cerebral adquirido (DCA). Participaron 78 cuidadores (75.6% mujeres) de edades comprendidas entre 22 y 80 años. Los participantes facilitaron medidas de problemas conductuales y emocionales de la persona con DCA, rasgo de mindfulness, síntomas de ansiedad y depresión, calidad de vida y rumiación. Los resultados mostraron que mindfulness se asocia a menos síntomas de ansiedad y depresión y más calidad de vida y que esto se explica a través de un menor uso de la rumiación. Asimismo, los problemas conductuales y emocionales de la persona con DCA se asocian a una mayor depresión y menor calidad de vida en el cuidador. La rumiación media parte de esta asociación. Finalmente, los problemas conductuales y emocionales de la persona con DCA se asocian más estrechamente a la depresión en los cuidadores con bajo nivel de mindfulness.

Palabras clave

Da├▒o cerebral adquirido, Cuidadores familiares, Rumiaci├│n, Calidad de vidaKeywords

Acquired brain injury, Family caregivers, Rumination, Quality of lifeCite this article as: Calvete, E., Franco, M. A. R., Oñate, L., Alonso, M. S., and Bermejo-Toro, L. (2021). Trait Mindfulness, Rumination, and Well-being in Family Caregivers of People with Acquired Brain Injury. Cl├şnica y Salud, 32(2), 71 - 77. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2021a5

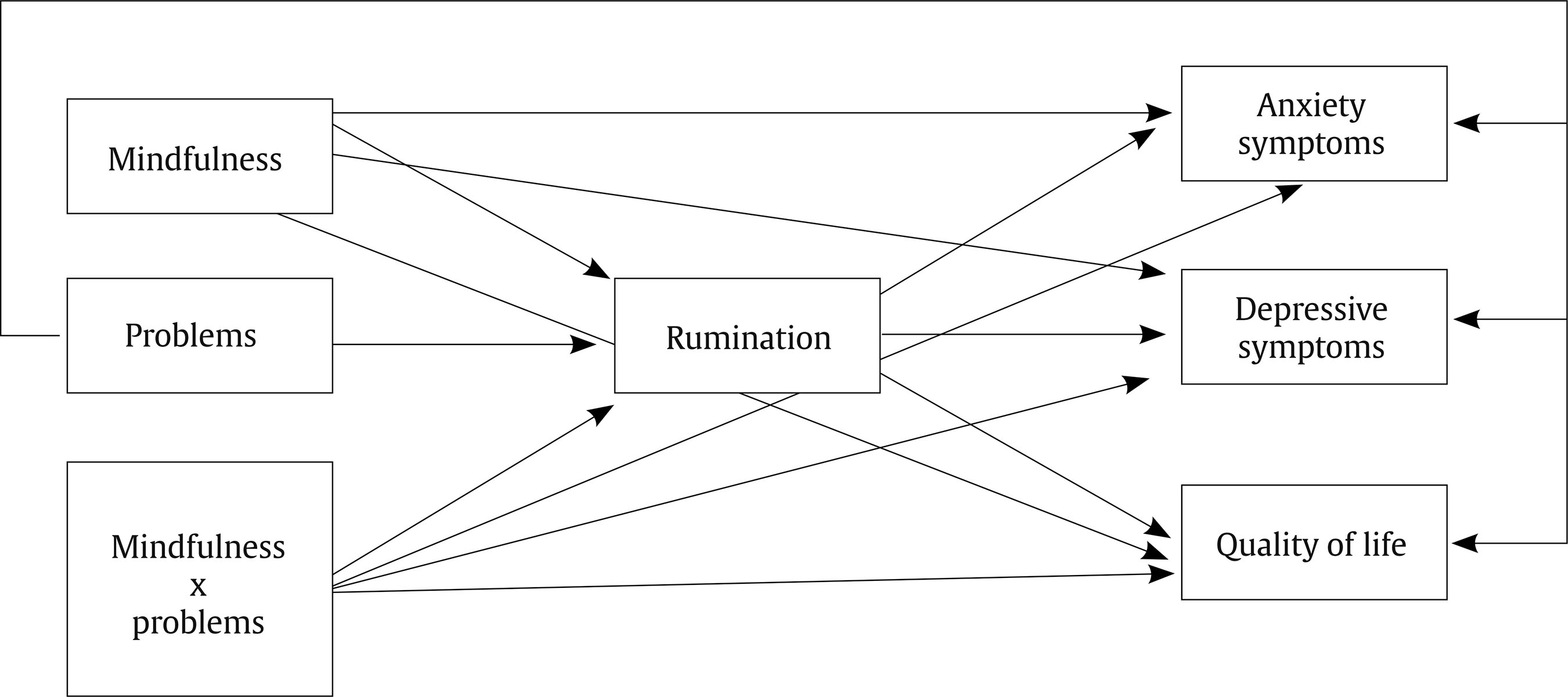

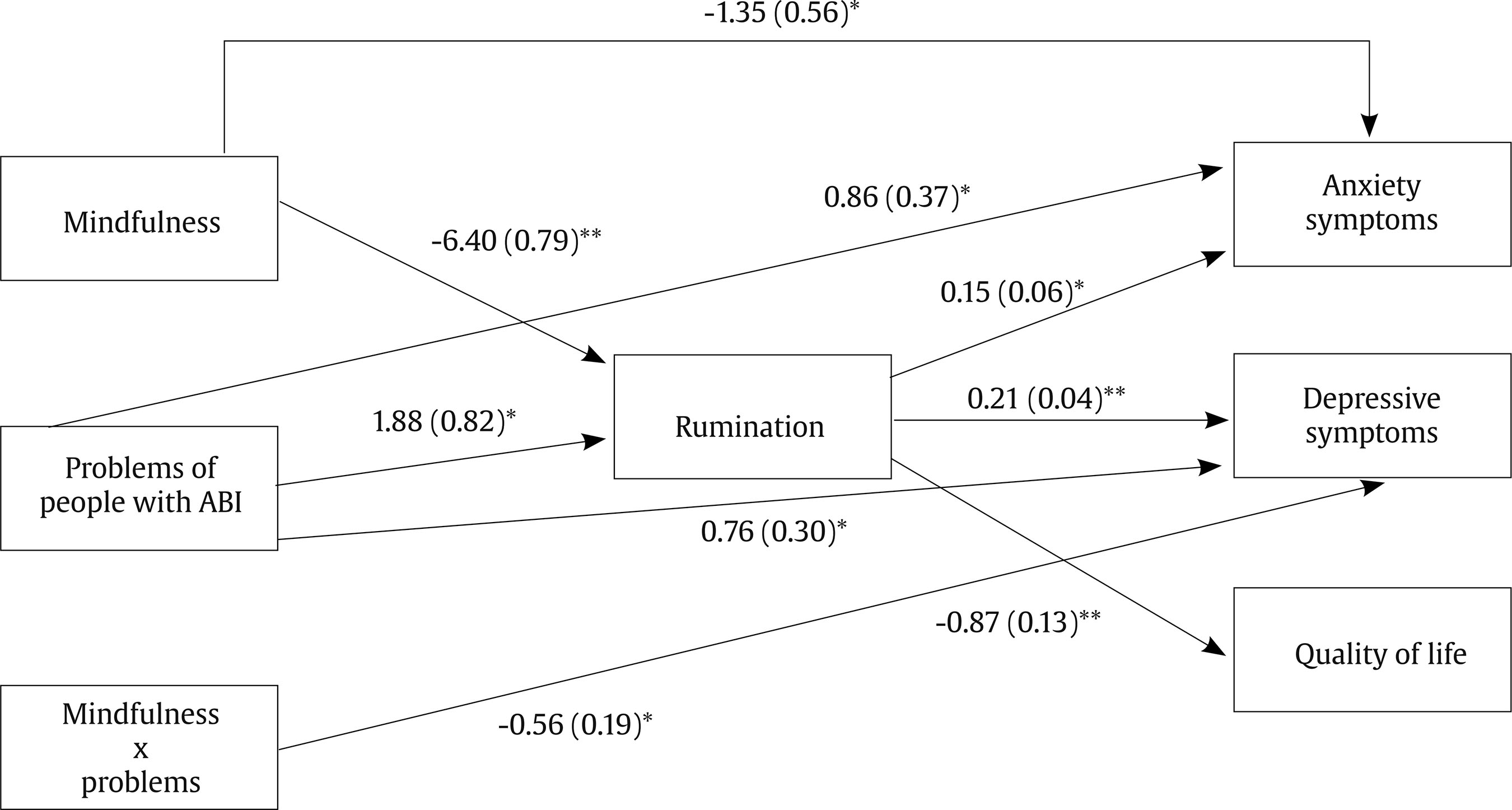

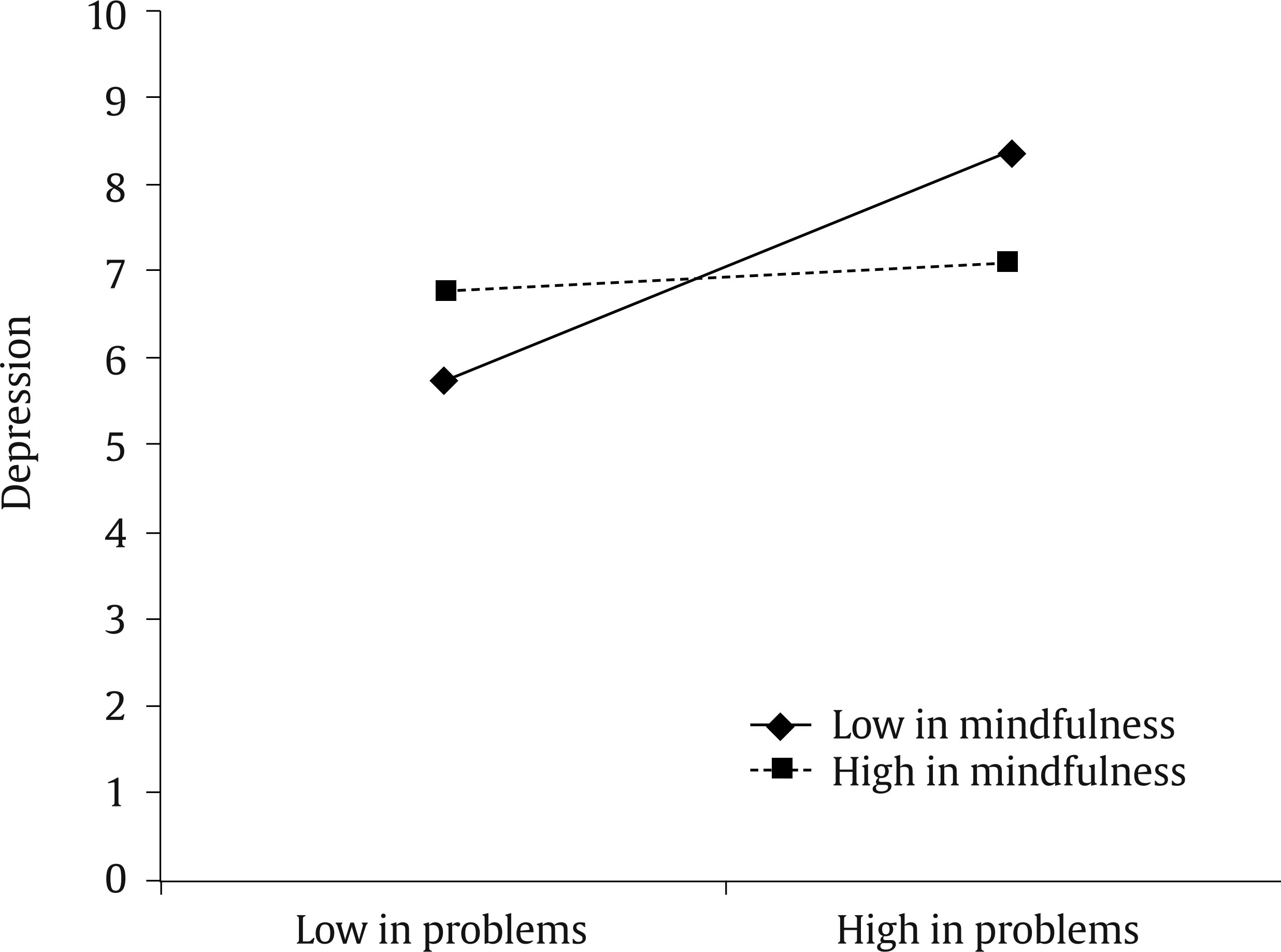

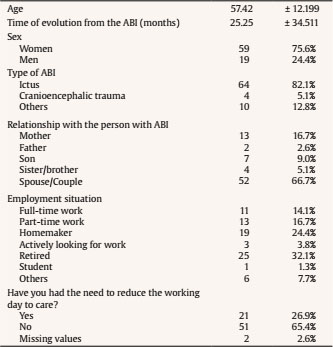

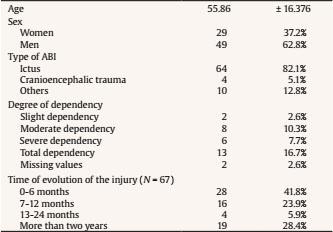

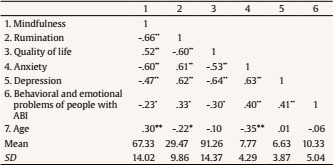

aroldan@comillas.edu Correspondence: aroldan@comillas.edu (M. A. Rold├ín Franco).Acquired brain injury (ABI) is a major public health problem and one of the main causes of disability and death worldwide (Chan et al., 2009). ABI includes a variety of brain injuries that can happen suddenly and unexpectedly in a person’s life as a result of a stroke or traumatic brain injury. As a result of ABI, an individual may experience limitations and loss of functionality in several areas. Family members often have to assume the role of caregivers and the responsibility to support a person living with ABI in numerous physical, cognitive, economic, financial, social, and leisure activities (Verhaeghe et al., 2005). In addition, people with ABI frequently experience emotional and behavioral problems that family caregivers have to deal with (López de Arroyabe et al., 2013). All in all, caring for a person with ABI can become a source of stress for family members, especially when the care required is extended over time without adequate formal and informal support resources (Calvete & López de Arroyabe, 2012). As a consequence, caregivers often experience symptoms of anxiety and depression and a decline in their own quality of life (Las Hayas et al., 2015). These consequences are negative not only for the caregiver, since they entail suffering and discomfort for the caregiver, but also for the person with ABI, given that the quality of care can be negatively affected (Sander et al., 2012). Based on the stress and coping process, several studies have shown consistently that caring for an older family member with chronic health problems and functional limitations or dementia (e.g., Knight & Sayegh, 2010; Losada et al., 2010; Sörensen & Pinquart, 2005) is associated with negative mental and physical health outcomes. Furthermore, theoretical models include psychosocial, physiological, biomedical variables (e.g., Vitaliano et al., 2002), and dysfunctional thoughts (e.g., Losada et al., 2010) as relevant factors to understand the stress of caregiving. Due to the above issues, numerous studies have focused on caregivers’ distress and the identification of protective factors that can contribute to resilience and the reduction of their psychological symptoms and improve their quality of life (Baker et al., 2017; Las Hayas et al., 2015). In addition to social factors, such as the formal and informal support, among the protective factors are those individual characteristics of caregivers that can be modified through intervention. One of these characteristics is trait mindfulness, which is the subject of enormous interest in current research. Mindfulness has been described as “the consciousness that emerges through paying attention intentionally in the present moment, and in a non-evaluative way, to things as they are” (Williams et al., 2007, p. 47). The concept of mindfulness has been used in different ways over the last years. In this way, mindfulness can be considered a state, a process that involves self-regulation of attention, or a trait that everyone has to a greater or lesser extent (Bishop et al., 2004; Brown & Ryan, 2003; Hervás et al., 2016; Kabat-Zinn, 1990). In addition, we also call mindfulness the meditative practice that involves activating mindfulness as a state and process and whose purpose is to increase mindfulness as a trait (Hervás et al., 2016). Trait mindfulness is a complex construct and includes several facets (Baer et al., 2006). One of these facets, acting with awareness, is considered a central component of trait mindfulness (Bishop et al., 2004; Brown & Ryan, 2003) and is the focus of the current study. Acting with awareness consists of a tendency to attend to the present moment, as opposed to acting mechanically or in pilot mode (Baer et al., 2006). In general, studies indicate that trait mindfulness is associated with better psychological health and protect against the development of depression and other pathological symptoms (see for a review Tomlinson et al., 2018). The benefits of mindfulness have also been found in studies with family caregivers. In this way, mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to be beneficial for the relatives of people with neurological and chronic problems, reducing the perceived burden of the caregiver, as well as psychological symptoms of anxiety and depression, and improving their quality of life (see for a review Piersol et al., 2017). On the other hand, the studies that have examined trait mindfulness in caregivers have found its association with fewer psychological symptoms of anxiety and depression, as well as a better quality of life (Pagnini et al., 2015; Weisman de Mamani et al., 2018). In addition, studies with family caregivers have shown that acting with the awareness facet of mindfulness is especially beneficial in this group (Oñate & Calvete, 2019). An unresolved question refers to the mechanisms through which trait mindfulness is associated with fewer psychological symptoms and better quality of life in caregivers. A potential explanation is that trait mindfulness would reduce the negative impact of the stress experienced by caregivers. Different studies have shown that trait mindfulness moderates the relationship between stressors and mental health (e.g., Conner & White, 2014; de Frias & Whine, 2014; Vara-García et al., 2019). This protective role of trait mindfulness has been also reported in different studies with caregivers, where mindfulness moderates the negative impact of stressors (e.g., Conner & White, 2014; Vara-García et al., 2019). Previous research has indicated that rumination is a mediational mechanism for the beneficial role of mindfulness (van der Velden et al., 2015). Thus, rumination would be less frequent in people characterized by a high mindfulness trait (Jury & Jose, 2018). Rumination has been described as a response to negative mood, which includes automatic behaviors and thoughts about symptoms of psychological distress and their implications (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). People with a ruminative style tend to wallow in their symptoms, wondering about causes and regretting their situation, which would contribute to the duration and increase in the severity of the symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). Rumination includes two components (Treynor et al., 2003): brooding and reflection. Brooding consists of a passive and contemplative attitude that compares the current situation with a standard unachieved situation with an attitude of regret and has been considered the more harmful component of rumination. Reflection is focused to find a cognitive solution to the problem (Treynor et al., 2003). Although initially the rumination construct was developed to explain the onset and perpetuation of depression, it has been found to also be a risk factor for anxiety and a poorer quality of life (Parola et al., 2017). The role of rumination has also been examined in different samples of family caregivers, being associated with higher levels of distress, such as anxiety and depression, experienced by a caregiver (Perlick et al., 2012). In addition, Romero-Moreno et al. (2016) found that rumination mediated the association between stressors and anxiety in family caregivers of people with dementia. Therefore, previous research indicates that trait mindfulness is associated with better health indicators (Tomlinson et al., 2018) and can reduce the negative impact of stress in mental health (Cortazar & Calvete, 2019; de Frias & Whine, 2014). Moreover, rumination has been proposed as a mediational mechanism to explain the role of mindfulness (van der Velden et al., 2015). Grounded in these previous findings, the present study aimed to explore some of the mechanisms through which trait mindfulness is beneficial for caregivers of people with ABI. We hypothesized the following: (1) higher levels of trait mindfulness will be associated with higher levels of quality of life and lower levels of anxious and depressive symptoms; (2) the association between the presence of emotional and behavioral problems in a person with ABI, and the quality of life and symptoms of anxiety and depression in caregivers would be lower when trait mindfulness is high; (3) rumination would act as a mediating variable of the association between mindfulness trait, emotional and behavioral problems of a person with ABI, and interaction between these variables, on the one hand, and a caregiver’s quality of life and distress symptoms, on the other. Figure 1 displays the hypothetical model. Figure 1 Hypothetical Model between Problems of the Person with ABI, Trait Mindfulness, Rumination, and Well-being of the Caregiver.   Participants Characteristics of family caregivers. In order to participate in this study, relatives had to be the primary caregiver of a person with ABI. That is, they should: (l) carry out care and support tasks (on daily life tasks, such as eating, bathing, and walking) for a person with ABI, and make decisions on different aspects of life (health, occupations, economy) that concern a person with ABI, regardless of whether they live with him/her or not, and/or (2) be the family member who accompanies or cares for the affected person for the most hours, both daily and weekly. Caregivers were asked for these questions in the first contact with them to check if they met these inclusion criteria. Table 1 presents the main characteristics of family caregivers; 76.6% of participants were women and 24.4% were men. Mean age was 57.42 years (SD = 12.2), ranging from 22 to 80. Most of the caregivers were spouses (66.7%) or parents (19.3%). Regarding the employment situation, the most frequent reported categories were “retired” (32.1%) and “homemakers” (24.4%) Table 2 shows the main characteristics of people with ABI who were supported by participants; 37.2% were women, 62.8% were men, with an average age of 55.86 years (SD = 16.37). Stroke was the prevailing type of brain injury (82%). Mean time elapsed since the injury was 25.3 months (SD = 34.51), ranging from 2 months to 14 years in total. In relation to the degree of dependence reported by the caregiver, 16.7% of people with ABI had total dependence, 7.7% severe dependence, 10.3% moderate dependence, and 2.6% mild dependence. Measures Mindfulness. The Spanish version (Soler et al., 2011) of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, 2003) was used to evaluate the acting with awareness trait of mindfulness. The MAAS is a 15-item instrument to measure mindfulness as a single factor (for example, reverse scoring elements “I eat a snack without being aware that I am eating”, “I find myself doing things without paying attention”). The response format varies from 1 (almost never) to 6 (almost always). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .87. Anxiety and depression. The Spanish version (Tejero et al., 1986) of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond & Snaith, 1983) was used to evaluate the symptoms of anxiety and depression. The HADS consists of two subscales of seven items that provide a score for anxiety and depression. Each item has four response options ranging from 0 (never or none) to 3 (always or often). Despite HADS was initially built in hospital settings, this measure has been widely used in community samples and in family caregivers (Beer et al., 2013; Jones et al., 2014; Lloyd & Hastings, 2008) maintaining good reliability. Alpha coefficients were .82 and .76 for anxiety and depression, respectively. Quality of life. The Spanish version (Espinoza et al., 2011) of the World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF; Skevington et al., 2004) was used to evaluate the quality of life. It consists of 26 items that measure various dimensions of quality of life (physical health, psychological health, social relations, and environmental quality of life) The items have a Likert scale of five points, ranging from 1 (no, never) to 5 (always, totally) In this study, the scale total obtained an alpha of .89. Rumination. A version of the Spanish adaptation (Hervás, 2008) of the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) was used to assess the tendency of family caregivers to present a ruminative thinking style when experiencing negative emotions. The RSS version used in this study is made up of 17 items that assess the brooding component of rumination and were adapted to care (e.g., you think “I will not be able to do my work/homework if I am not able to get rid of this”). The items are answered on a scale between 1 (almost never) and 4 (almost always). Alfa coefficient was .92. Emotional and behavioral problems of the person with ABI. The Spanish-Relative Version (López de Arroyabe et al., 2013) of the Head Injury Behavior Scale (HIBS; Godfrey et al., 2003) was used to assess emotional and behavioral problems. The Spanish version is an extension of the original HIBS, where seven additional elements were added to complete some of the subscales. Therefore, the HIBS consists of 28 elements that evaluate the common psychological problems that occur after a brain injury. These elements refer to difficulties in emotional regulation (for example, sudden/rapid changes in mood, depression, discouragement) and regulation of behavior (for example, lack of control over behavior, inappropriate behavior in social situations, lack of motivation, or lack of interest in doing things). Caregivers should indicate in a dichotomous way (yes/no) if each of the problem behaviors occurs or not. The sum of the emotional and behavioral problems reported by the caregivers is calculated as an indicator of the presence of these problems in the person with ABI. Procedure To collect the sample, we contacted different centers and associations (Federación Española de Daño Cerebral-FEDACE, day centers, and hospitals), from different Spanish cities (Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, and Palma de Mallorca). We sent a summary of the research along with a letter of introduction to inform relatives, requesting their collaboration in the study. Caregivers agreeing to participate in the research signed an informed consent and provided contact information; later the research team contacted on how they would prefer to answer the questionnaire. The application of questionnaires was carried out in three different ways: a telephone interview conducted by a trained psychologist (N = 53), an on-line questionnaire (N = 22), and in writing with subsequent reply by post or email (N = 3). Data provided by participants were treated carefully, preserving anonymity and confidentiality. Statistical Analysis We used path analysis with LISREL 10.2 with the robust maximum likelihood method, which requires an estimate of the asymptotic covariance matrix of the sample variances and covariances and includes Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 index (S-B χ2). The hypothesized model included paths from mindfulness, behavioral/emotional problems in an individual with ABI, and from the mindfulness x behavioral/emotional problems interaction term, to rumination, quality of life, and symptoms of anxiety and depression. The model also included paths from rumination to quality of life and symptoms. As the study was cross-sectional, in order to obtain stronger evidence for the hypothesized model we tested an alternative model in which mindfulness was included as an explanation of associations between rumination, behavioral/emotional problems, and the rumination x behavioral/emotional problems interaction and quality of life and distress symptoms. To create interaction terms, variables were transformed into z scores, following the standard procedure to examine moderation effects (Frazier et al., 2004). Model’s goodness of fit was evaluated using the comparative fit index (CFI), the non-normative fit index (NNFI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), which is recommended for small samples (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Generally, CFI, and NNFI values of .95 or higher reflect a good fit. SRMR values lower than .08 indicate an excellent fit. Significance of the indirect effects was tested by means of 5,000 bootstrapping samples. Table 3 shows correlation coefficients between variables. Trait mindfulness was negatively associated with a caregiver’s rumination and distress symptoms, as well as positively with quality of life. Age was positively associated with mindfulness and negatively with rumination and quality of life. Behavioral and emotional problems of the family member were negatively associated with mindfulness and quality of life, and positively with rumination and anxiety and depression. Next, we tested the hypothesized model. Mindfulness was negatively associated with rumination, whereas the number of behavioral/emotional problems in the individual with ABI was positively associated with rumination undergone by the caregiver. Rumination in turn was associated with less quality of life and higher scores on anxiety and depression. Trait mindfulness was directly associated with less anxiety, and behavioral/emotional problems were associated with higher scores on anxiety and depression. Interaction between mindfulness and behavioral/emotional problems was statistically significant for depression. Fit indexes were excellent, S-B χ2(2, 78) = 0.96, NNFI = 1.00, CFI = 1.00, SRMR = .03. A more parsimonious model was estimated with only significant paths. This model is displayed in Figure 2. Fit indexes were excellent, S-B χ2(7, 78) = 6.19, NNFI = 1.00, CFI = 1.00, SRMR = .05. Figure 3 displays the form of the interaction for caregivers low (1 SD below the mean) and high (1 SD above the mean) in mindfulness and behavioral/emotional problems of the person with ABI. When mindfulness is high, there is not association between problems and depression (B = 0.18, t = 0.36, p = .72), whereas, when mindfulness is low, the association is statistically significant (B = 1.30, t =2.25, p = .027). Figure 2 Estimated Model between the Behavioral and Emotional Problems of the Person with ABI, Mindfulness, Rumination, and Well-being of the Caregiver.   Figure 3 Interaction between Caregivers’ Trait Mindfulness and Behavioral and Emotional Problems of People with ABI for Depression.   The path analysis model indicates several potential indirect paths between variables. These indirect effects were tested through 5,000 bootstrapping samples (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Indirect associations between mindfulness and well-being indicators through rumination were statistically significant for quality of life (95% CI [5.23, 5.29]), anxiety (95% CI [-0.91, -0.86]), and depression (95% CI [-1.28, -1.26]). Similarly, indirect associations between behavioral/emotional problems and well-being indicators through rumination were statistically significant for quality of life (95% CI [-1.64,-1.60]), anxiety (95% CI [0.28, 0.29]), and depression (95% CI [0.39, 0.41]). Finally, we tested the alternative model, in which mindfulness was included as a mechanism explaining the association between rumination, and behavioral/emotional problems, the interaction term between both, and well-being indicators (quality of life, anxiety, and depression). Paths between rumination and mindfulness (B = -0.70, SE = 0.10, p < .001) and between mindfulness and anxiety (B = -1.52, SE = 0.58. p = .005) were statistically significant. However, paths between mindfulness and quality of life (B = 2.88, SE = 2.01, p = .08) and depression (B = -0.50, SE = 0.44. p = .13) were not statistically significant. The SRMR value for this model was not adequate, S-B χ2(2, 78) = 0.93, NNFI = .930, CFI = .99, SRMR = .10. Therefore, the hypothesized model was considered a better explanation of the association between variables. Caring a person with ABI can be a major source of stress for family caregivers, especially when a person displays behavioral and emotional problems (López de Arroyabe et al., 2013) and dependence (López de Arroyabe & Calvete, 2013). Therefore, it is important to identify protective and resilience factors that can be developed in family caregivers. The present study aimed to explore the beneficial role of trait mindfulness and some of the mechanisms through which it is beneficial for caregivers. The results of this study indicate that the acting with awareness trait of mindfulness may be one of those resilience factors. Trait mindfulness was directly associated with less anxiety in caregivers. Moreover, it was indirectly associated with less depression and with a higher quality of life through lower use of ruminative thinking in caregivers. These results are not surprising and are consistent with findings of previous studies that find that trait mindfulness in general and acting with awareness in particular are associated with fewer psychological symptoms (Weisman de Mamani et al., 2018) and better quality of life (Oñate & Calvete, 2019; Weisman de Mamani et al., 2018) in family caregivers of people with different neurological problems. The results of this study also indicate the importance of behavioral and emotional problems of individuals with ABI as a potential source of stress in caregivers. In our study, the number of problems of this nature was significantly associated with lower quality of life and more symptoms of anxiety and depression in caregivers. Other studies have also found that this type of problem acts as a risk factor for psychological problems in caregivers of people with ABI (López de Arroyabe et al., 2013) as well as people with other disabilities (Chappell & Penning, 1996). We expected to find that trait mindfulness buffered the association between behavioral and emotional problems in a person with ABI and the rest of variables. However, this moderation effect was significant only for depression. The association between behavioral/emotional problems and depression was not statistically significant among caregivers who scored high in trait mindfulness. This finding is consistent with previous studies that found that trait mindfulness reduces the impact of stressors in mental health (Cortazar & Calvete, 2019; de Frias & Whine, 2014; Dixon & Overall, 2016). Rumination played a relevant role as an explanatory mechanism for the association between mindfulness and well-being in caregivers. This finding is important because it helps to understand why trait mindfulness is a beneficial factor. Non-evaluative awareness of experiences, as they are in the present moment, is in some way incompatible with a ruminative process of focusing on negative moods and unfavorable circumstances. In addition, rumination explained the association between behavioral/emotional problems in a person with ABI and caregivers’ symptoms of anxiety and depression. This result is consistent with findings of studies that show that stressors lead to greater use of rumination (Barchia & Bussey, 2010), something found in studies with family caregivers (Romero-Moreno et al., 2016), where caregivers who reported having more stressors also reported a higher level of rumination. This study has important limitations. The main limitation is that it uses a non-probability sampling and the small size of the sample. Recruitment of family caregivers is complex because of their lack of free time as a consequence of their caregiving role. Due to the small size of the sample, in this study we focus on a simple path analysis model with very few variables. Future studies should replicate the results with larger samples and with additional variables, such as coping responses, social support resources, age, and sex. In fact, in this study age was positively associated with mindfulness and negatively with rumination and anxiety. This finding could suggest a better adaptation in oldest caregivers. Thus, future research should examine the role of age in this process. Another limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the study. Although caregivers were followed up over time, attrition was very high, and only a few completed follow-up measures. A strict mediation test would require longitudinal measurements. However, this study can serve as an approximation, giving rise to future longitudinal investigations. Finally, this study used MAAS as a measure of trait mindfulness. Although the acting with awareness trait of mindfulness assessed by this questionnaire is central to the mindfulness construct (Bishop et al., 2004), research has shown the multidimensional nature of trait mindfulness and the existence of different interrelated but clearly differentiated facets (Baer et al., 2006). One of these facets, consisting of observing and being aware of different internal and external experiences, has found different results in non-meditative samples associated with a greater use of rumination (Royuela-Colomer & Calvete, 2016). Therefore, in future studies it would be appropriate to explore the role of different facets of trait mindfulness in family caregivers of people with ABI. In summary, trait mindfulness seems to play an important role in caregivers’ wellbeing since it is associated with fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression and better quality of life. These findings are in line with other studies suggesting that mindfulness interventions are beneficial for caregivers (e.g., Ho et al., 2016; Hou et al., 2014; Whitebird et al., 2013). Moreover, mindfulness-based interventions have been found to reduce negative rumination (Heeren & Philippot, 2011). Therefore, these interventions should also explicitly encourage the reduced use of ruminative responses to the difficulties experienced in caring for a person with ABI. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Funding: This research was supported by a grant from Aristos Campus Mundus Program and from the Basque Country (Ref. IT982-16) Cite this article as: Calvete, E., Roldan Franco, M. A., Oñate, L., Sánchez-Izquierdo Alonso, M., & Bermejo-Toro, L. (2021). Trait mindfulness, rumination, and well-being in family caregivers of people with acquired brain injury. Clínica y Salud, 32(2), 71-77. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2021a5 References |

Cite this article as: Calvete, E., Franco, M. A. R., Oñate, L., Alonso, M. S., and Bermejo-Toro, L. (2021). Trait Mindfulness, Rumination, and Well-being in Family Caregivers of People with Acquired Brain Injury. Cl├şnica y Salud, 32(2), 71 - 77. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2021a5

aroldan@comillas.edu Correspondence: aroldan@comillas.edu (M. A. Rold├ín Franco).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS