Behavioral Activation for Treatment-resistant Depression: Theoretical Model and Intervention Protocol (BA-TRD)

[ActivaciĂłn conductual para el tratamiento de la depresiĂłn resistente al tratamiento: modelo teĂłrico y protocolo de intervenciĂłn (AC-DRT)]

Michel A. Reyes-Ortega1, Jorge Barraca2, 3, Jessica Zapata-Téllez4, Alejandra M. Castellanos-Espinosa1, and Joanna Jiménez-Pavón5

1Instituto de Terapia y Análisis de la Conducta, Ciudad de MĂ©xico, MĂ©xico; 2Facultad HM de Ciencias de la Salud de la Universidad Camilo JosĂ© Cela, Madrid, Spain; 3Instituto de InvestigaciĂłn Sanitaria HM Hospitales, Spain; 4Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y TecnologĂa, Instituto Nacional de PsiquiatrĂa “RamĂłn de la Fuente Muñiz”, Ciudad de MĂ©xico, MĂ©xico; 5ClĂnica de Trastornos Afectivos, Instituto Nacional de PsiquiatrĂa “RamĂłn de la Fuente Muñiz”, Ciudad de MĂ©xico, MĂ©xico

https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2024a17

Received 25 February 2024, Accepted 28 June 2024

Abstract

Background: Treatment-resistant depression (TRD) is a severe public health problem and a condition uncommonly addressed by psychological therapies. This paper presents a theoretical model, grounded in established learning principles and in the perspective of behavioral activation (BA), to explain its constitution and development. Method: A review of theoretical models and empirical research on TRD was conducted in major databases. Results: The model reflects how patients with TRD are more susceptible to becoming trapped in their condition by seeking to avoid discomfort through avoidance and escape behaviors, which increasingly drives them away from sources of positive reinforcement. Based on this model, a BA-based intervention protocol is suggested for the treatment of TRD. Through six phases (in a total of thirteen sessions), the protocol guides the intervention towards the reestablishment of personalized routines to increase the probability of reinforcement and reduce avoidance behaviors. Conclusions: Although the model holds significant potential to become an effective intervention in TRD, future research will allow the evaluation of the efficacy of the protocol as a standalone intervention.

Resumen

Antecedentes: La depresión resistente al tratamiento (DRT) constituye un severo problema de salud pública y es una condición poco abordada por las terapias psicológicas. En este artículo se presenta un modelo teórico, fundamentado en contrastados principios de aprendizaje y en el modelo de activación conductual (AC) para explicar su constitución y desarrollo. Método: Una revisión de los modelos teóricos y una investigación empírica de la depresión resistente al tratamiento se llevó a cabo a través de las principales bases de datos. Resultados: El modelo refleja cómo los pacientes con DRT son más propensos a quedar atrapados en su estado al procurar evitar el malestar por medio de comportamientos de evitación y escape, lo que les aleja cada vez más de las fuentes de reforzamiento positivo. A partir de este modelo se propone un protocolo de intervención basado en la AC para el tratamiento de la DRT. A través de seis fases (en un total de trece sesiones) el protocolo orienta la intervención hacia el restablecimiento de rutinas personalizadas para aumentar la probabilidad del refuerzo y reducir los comportamientos de evitación. Conclusiones: Aunque este modelo cuenta con un potencial significativo de llegar a ser una intervención eficaz en el tratamiento de la depresión resistente al tratamiento, la investigación futura permitirá medir la eficacia del protocolo como intervención única.

Palabras clave

ActivaciĂłn conductual, DepresiĂłn resistente al tratamiento, Protocolo de tratamiento, Trastorno depresivo mayor, TeorĂa de la depresiĂłn resistente al tratamientoKeywords

Behavioral activation, Treatment-resistant depression, Treatment protocol, Major depressive disorder, Treatment-resistant depression theoryCite this article as: Reyes-Ortega, M. A., Barraca, J., Zapata-Téllez, J., Castellanos-Espinosa, A. M., & Jiménez-Pavón, J. (2024). Behavioral Activation for Treatment-resistant Depression: Theoretical Model and Intervention Protocol (BA-TRD). ClĂnica y Salud, 35(3), 135 - 140. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2024a17

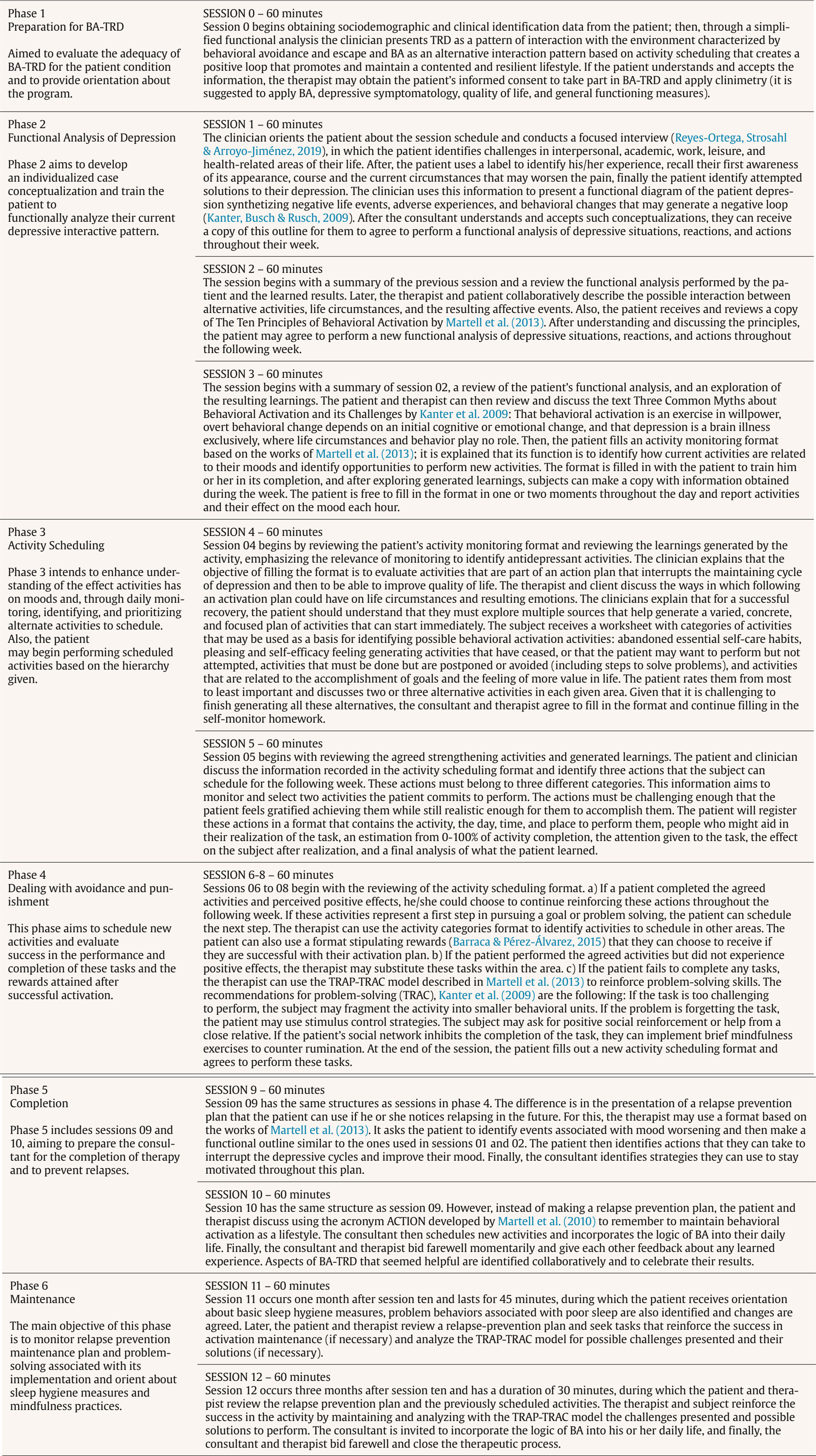

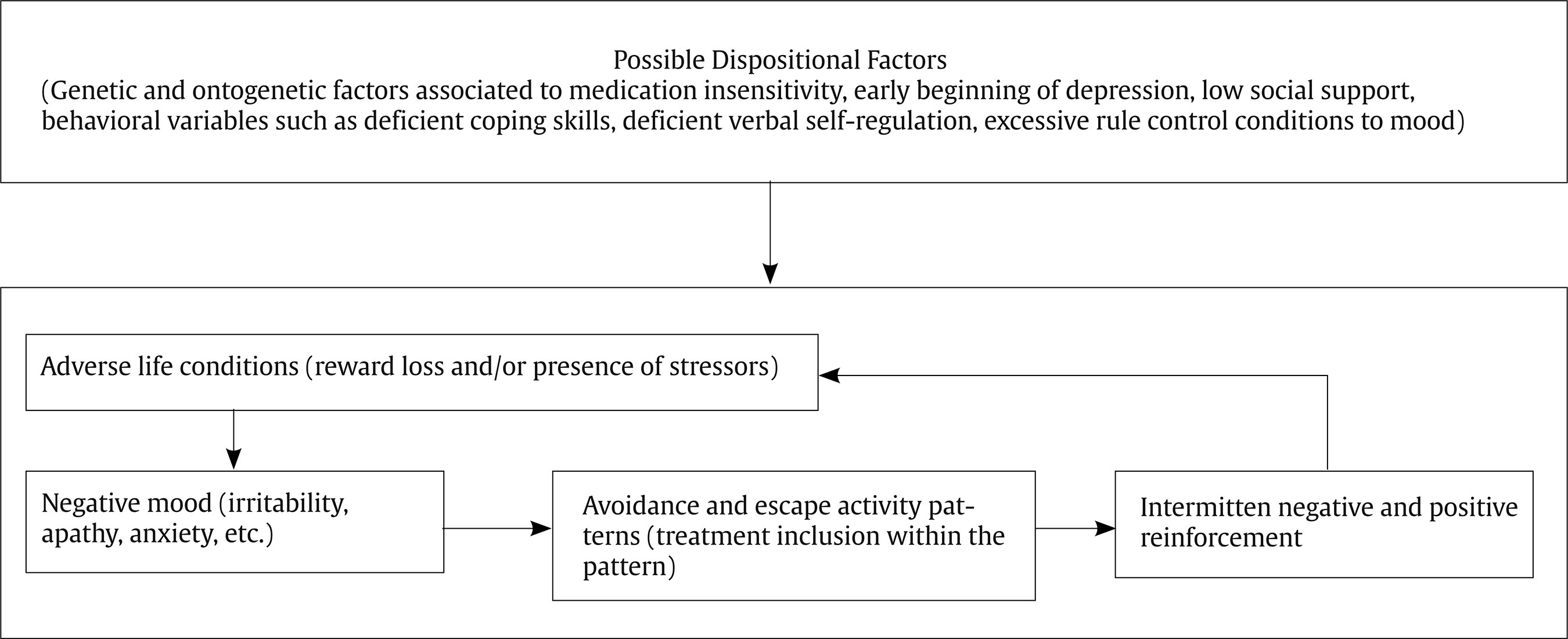

Correspondence: jbarraca@ucjc.edu (J. Barraca).The term Treatment-resistant Depression (TRD) denotes individuals diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) who exhibit no improvement following prescribed pharmacological interventions (Fawcett & Kravitz, 1985; Heimann, 1974). TRD represents a complex clinical entity encompassing various subtypes unresponsive to treatment. It is widely recognized among the most challenging clinical manifestations of depressive disorders, leading to substantial treatment costs. Moreover, TRD patients are twice as likely to require hospitalization, incurring hospitalization costs six times higher than the average for non-TRD patients. Furthermore, TRD is associated with poorer long-term outcomes, including functional decline, heightened risk of relapse, and increased incidence of suicidal attempts compared to those achieving complete remission (Corrales et al., 2020). At present, there is no universally accepted consensus regarding the criteria for identifying TRD. The prevailing conceptualization of TRD is pharmacological and involves the lack of response to two or more trials of monotherapy with distinct antidepressants, each administered separately at an appropriate dosage over a defined duration (Berlim & Turecki, 2010). However, it is surprising that a definition of psychological TRD has not been proposed independently from the medical-psychiatric perspective, even more so when several studies have suggested that medication could indeed be a factor contributing to the chronification of depression (Fava, 2003; Gøtzsche, 2014). We hope that new definitions emerge from psychology to compensate for this situation. Psychotherapy in Treatment-resistant Depression While research findings do not unequivocally endorse psychotherapy as a standalone intervention for TRD, it is widely acknowledged that the adjunct of personalized depression-focused psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy may increase the probability of superior outcomes (Álvarez et al., 2008; Spijker et al., 2013). In fact, it has become increasingly recognized that addressing TRD needs the formulation of a psychotherapeutic plan in conjunction with pharmacological treatment, to the extent that discussing TRD without first outlining a psychotherapeutic approach alongside pharmacotherapy is deemed untenable (Barsaglini et al., 2014; Steinert et al., 2014). However, research on the effectiveness of psychotherapy in treating TRD is comparatively scarce compared to pharmacological approaches. Consequently, the relative efficacy of various psychotherapeutic interventions remains largely unknown. Recent studies aimed at validating psychotherapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy have investigated cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), the cognitive-behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy (CBASP), radically open dialectical behavioral therapy (RO-DBT), and behavioral activation (BA). Meta-analytic research focusing on CBT has reported effect sizes (Cohen’s d) ranging from 0.23 to 0.38 in depression severity scores compared to control groups (Cuijpers et al., 2010; Wiles et al., 2016). However, most participants completed at least five sessions of the same intervention before enrolling in these studies, potentially biasing results towards those still benefiting from therapy. Moreover, these studies typically included subjects with TRD level 1 (one failed antidepressant trial), potentially limiting their applicability to individuals with more severe resistance. For CBASP, a meta-analysis revealed effect sizes (Cohen’s d) varying from 0.34 to 0.50 in depression severity, with remission rates ranging between 19% and 57% in experimental groups compared to 6% to 50% in control groups (Michalak et al., 2015; Negt et al., 2016). Critics argue that CBASP was primarily developed for dysthymia treatment and may not be parsimonious, requiring a minimum of 30 sessions. Randomized trials of RO-DBT reported post-treatment remission rates of 71% in the experimental group compared to 47% in the control group, with corresponding rates of 75% and 31% after six months (Lynch et al., 2007; Lynch et al., 2018; Lynch et al., 2003; Lynch et al., 2015). Notably, RO-DBT was initially developed to treat internalizing personality disorders, suggesting its potential efficacy for TRD with comorbid personality disorders. However, its implementation is resource-intensive, requiring significant time and highly trained clinicians. Behavioral Activation for Depression The foundation of BA stems from a longstanding tradition of behavioral theory and research. BA is a brief, structured treatment that focuses on activating individuals by prompting behaviors facilitating contact with diverse and stable sources of positive reinforcement, with activity scheduling serving as its central strategy (Santos et al., 2021). Additionally, BA aims to reduce avoidance and escape behaviors (Martell et al., 2013) while fostering the development of coping skills (Kanter et al., 2009) to initiate change (Kanter & Puspitasari, 2012). As a clinical procedure, BA encompasses four competencies: presentation of behavioral activation, activity evaluation, activity scheduling, and addressing avoidance (Kanter et al., 2009; Puspitasari et al., 2013). Studies evaluating BA for TRD report effect sizes (Cohen’s d) ranging from 0.52 to 0.67 concerning waiting list (pharmacotherapy alone) comparisons, depression severity, life quality, and attachment to pharmacological treatment (Dobson et al., 2010; Shinohara et al., 2013). While no specific clinical trials exist for TRD, a comprehensive analysis (Coffman et al., 2007) within a broader randomized clinical trial compared the efficacy of BA, CBT, and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) (Dimidjian et al., 2006). Results indicated that individuals with severe, longstanding interpersonal problems and depression responded better to BA (plus an SSRI) compared to CBT. BA is recognized as a therapeutic intervention with robust evidence for MDD treatment by Division 12 of the American Psychological Association (APA), supported by at least two well-designed studies conducted by independent researchers (APA, 2022). Single-case experimental designs (Barraca, 2010) and nomothetic research have contributed to meta-analytic evidence demonstrating BA’s efficacy compared to various pharmacological and psychological treatments, particularly CBT, with favorable outcomes for BA (Cuijpers et al., 2010). Moreover, BA has demonstrated utility in environments where traditional clinical treatments are challenging due to time constraints or limited human resources, such as public health contexts. Another advantage of BA over other therapies is its relatively shorter training period for therapists and implementation length, as it addresses specific issues and promotes recovery in a reduced number of sessions. Coherently with the above revision, the aim of this paper is to propose a theoretical therapeutic plan for TRD and outline an intervention protocol for its implementation. Behavioral theory of Treatment-resistant Depression Similar to the behavioral theory of depression in BA, the behavioral theory of TRD (BT-TRD) posits depression as a reinforcement trap (Baum, 2017). In this trap, individuals adhere to pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments that have demonstrated effectiveness in order to avoid delayed gratification, immediate distress, or the low probability of gratification, thus perpetuating the cycle of depression. According to the theory, the relief derived from these strategies involves negative reinforcement of avoidance and escape behaviors, leading to an increase in the frequency and duration of negative behaviors. Over time, these response patterns can become ingrained, evolving into a lifestyle characterized by avoidance. Consequently, there is a progressive decrease in the frequency, persistence, duration, and complexity of pleasant activities or problem-solving efforts, leading to further dissatisfaction and the generation of additional stressors. These stressors are coped with using the same avoidant strategies, perpetuating an endless repetitive cycle. The theory suggests that, over time, the activity pattern directed towards distress avoidance may lose its efficacy or generate intermittent positive reinforcement. This unpredictability resembles the variable reinforcement programs associated with persistence, even if contingent reinforcement does not consistently follow the behavior (Ferster & Skinner, 1957). Types of Adversities and Consequences in BT-TRDÂ According to Ferster’ (1973) theory of depression, depressive states arise from individuals encountering adversity and its associated effects, resulting in a sudden decrease in positively reinforced activities. This decrease can stem from various sources, such as life changes leading to fewer opportunities for engaging in pleasant activities, the devaluation of rewards associated with these activities, or an increase in avoidance and escape behaviors competing with the pursuit of pleasurable activities. Lewinsohn (1974) described a similar condition, noting negative moods, reduced engagement in pleasant activities, and the emergence of avoidance and escape behaviors due to a decrease in contingent positive reinforcement. Another adverse scenario involves a sudden influx of unwanted effects in an individual’s usual activities or an increase in stressors unrelated to their actions. These factors can lead to negative moods, heightened avoidance behaviors, and the development of despair cognitions and low self-efficacy, also known as learned helplessness (Overmier & Seligman, 1967). Poor coping skills in the face of new stressors can exacerbate this condition, resulting from the failure of coping attempts and the eventual establishment of avoidance and escape patterns. Additionally, some individuals may struggle to organize and regulate their behavior effectively, leading to persistent but ineffective coping strategies. In certain cases, individuals may rigidly adhere to rules such as “I must feel good before changing my habits or solving my problems”, perpetuating avoidance behaviors. Instead of improving their situation, these avoidant mechanisms can exacerbate their circumstances, leading to further losses and stressors and reinforcing avoidance and escape behavior patterns (Martell et al., 2001). In summary, (a) life changes understood as a decrease in contingent reinforcement of regular activities, the loss of opportunities to engage in pleasant activities, the sudden increase in stressors or unwanted effects contingent to the individual’s habits, and possible deficits in coping skills when faced with adversity would result in (b) a decrease in behaviors oriented to positive reinforcement and an increase in avoidance and escape behaviors from the stressful or deprivation experience generated by the conditions previously described. (c) Both, the reinforcement of this avoidance and escape behaviors and a possible rule following of the type “I must feel good before I can change my habits or solve my problems”, and possible difficulties to organize behaviors in persistent activity patterns in the face of adversity, result in (d) the establishing of a lifestyle oriented to the avoidance of psychological distress that results in more reward loss and the surging of bigger stressors, in an abulic and anxious mood, in hopelessness cognitions, an external locus of control, low self-efficacy, low self-esteem, and hypoactivity in reward circuits, characteristics of depression. Eventually, intermittent reinforcement of avoidance and escape behaviors (and their eventual positive reinforcement), the use of medication or psychotherapy with the same avoidant goals, and the deterioration (due to disuse) of coping skills oriented to reward, problem-solving, and subsequent efficacy feeling included in pleasant activity patterns would generate a chronic depressive cycle resistant to treatment. Theoretically, dispositional factors such as disorders in the secondary neuroendocrine functional systems, non-genetic variants, weak support systems, early-onset depressive cycles with the presence of other affective symptoms, pre-existing interpersonal behavior disorders, or substance abuse are associated with the persistence of these depressive loops and its resistance to otherwise effective depression treatments. See Figure 1 for a synthetic representation of this theory. The BA-TRD intervention protocol consists of thirteen sessions aimed at generating personalized routines or activity patterns to enhance reward efficacy and enrichment across various life domains, including social relationships. After initially assessing whether the therapy is suitable for the case and collecting the necessary data to complete the functional analysis, in the intervention phase and in accordance with the BT-TRD, the primary objective of the program is to decrease avoidance and escape behaviors that impede problem-solving, compliance with self-care habits, and fulfillment of social obligations necessary for proper social adjustment. Secondarily, the protocol focuses on the establishment of appropriate habits, their reinforcement, and their generalization and maintenance to prevent relapses. See Figure 2 for a description of the phases and sessions of the BA-TRD intervention protocol. Figure 2 The General Structure of the Intervention Protocol BA-TRD   Note. Please contact the corresponding author to obtain the full protocol, including detailed descriptions of the activities performed in each session. Given its relevance and severe impact on health systems, TRD should be considered a problem to be addressed by psychological therapies, just as it has been in pharmacological ones. With this approach, and based on the BT-RDT, the BA-TRD protocol was developed to address alternative interventions for TRD. This protocol is proposed as an intervention which, based on previous research findings with BA, does not necessarily have to be combined with antidepressant medication. The intervention has the primary advantage of being brief, and it is estimated that its training for psychologists who are familiar with the BA model would require no more than up to eight hours of training. It is manualized and clearly defines the behavioral (positive reinforcement) mechanisms within the framework of BA. Future studies, which are already underway, will specify the training program and assess the impacts of the protocol described in this article. Although it is true that this protocol still requires empirical work for validation in TRD, it should be emphasized that it is based on the same principles of interventions with well-proven evidence in cases with severe MDD (Coffman et al., 2007). In addition, BA has also shown in large samples a better cost-effectiveness compared to antidepressant medication (Ekers et al., 2014) or with CBT (Muzzecchelli et al., 2010), including also large public health systems, such as the UK’s (Richards et al., 2016). Finally, we can say that the protocol adheres to criteria for maximum quality in experimental contrasting, emphasizing parsimony and ease of implementation (Cougle, 2012). Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Reyes-Ortega, M. A., Barraca, J., Zapata-Téllez, J., Castellanos-Espinosa, A. M., & Jiménez-Pavón, J. (2024). Behavioral activation for treatment-resistant depression: Theoretical model and intervention protocol (BA-TRD). Clínica y Salud, 35(3), 135-140. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2024a17 Highlights - Treatment-resistant Depression (TRD) is a complex condition that poses a crucial challenge for clinicians and public health. To date, approaches to this problem have been almost exclusively pharmacological, to the point that the definition of TRD is associated with failure with several psychopharmacological interventions and there is no consensus on its delimitation from psychological interventions. - Behavioral Activation (BA) has updated the analysis and interventions in depression. Thanks to its contributions and a re-reading of learning principles possibly associated with depression, an explanatory model has been developed to account for TRD. - Based on the explanatory model of TRD, a protocol of six phases and thirteen sessions has been developed for the approach of TRD. This protocol, which is presented in this paper, can be easily trained by therapists who are familiar with BA. Although it still requires more empirical work, its solid learning foundations and its link with previously successful BA interventions bode well for its usefulness to clinicians. References |

Cite this article as: Reyes-Ortega, M. A., Barraca, J., Zapata-Téllez, J., Castellanos-Espinosa, A. M., & Jiménez-Pavón, J. (2024). Behavioral Activation for Treatment-resistant Depression: Theoretical Model and Intervention Protocol (BA-TRD). ClĂnica y Salud, 35(3), 135 - 140. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2024a17

Correspondence: jbarraca@ucjc.edu (J. Barraca).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS