Preschoolers Daily Stress Scale, Parent’s Version

[Escala de Estrés Cotidiano Preescolar, versión para padres]

María T. Monjarás Rodríguez, Edith Romero Godínez, and Octavio Salvador Ginez

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Coyoacán, DF, México

https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2024a18

Received 15 December 2023, Accepted 16 July 2024

Abstract

Background: Daily stress in preschool children is associated with mental health problems such as anxiety and depression. However, the assessment of this construct is challenging, as multiple informants are required. Method: The aim of the present study was to adapt and validate the Preschool Daily Stress Scale to a parent version, as well as to obtain confirmatory analysis of the child version. Participants were 515 parents of preschoolers for the validation and reliability of the Daily Stress Scale in its parent version. For the confirmatory analysis of children’s version, 397 preschoolers participated. Results: The results showed that the Daily Stress Scale in its parent and children version has the same pattern of five stress factors: Fantasy and Fears, Conflict with peers, Conflict with siblings, Scholar Stress, and Parent Conflict. Conclusions: The Preschool Daily Stress Scale is valid and reliable and can be useful for both clinical and research purposes.

Resumen

Antecedentes: El estrés cotidiano de los niños en edad preescolar se asocia a problemas de salud mental como la ansiedad y la depresión. Sin embargo, la evaluación de este constructo supone un reto, ya que se requieren múltiples informantes. Método: El objetivo del presente estudio fue adaptar y validar la Escala de Estrés Diario en Preescolares a una versión para padres, así como obtener un análisis confirmatorio de la versión para niños. Los participantes fueron 515 padres de preescolares para la validación y fiabilidad de la Escala de Estrés Diario en su versión para padres. En el análisis confirmatorio de la versión infantil participaron 397 preescolares. Resultados: Los resultados mostraron que la Escala de Estrés Diario en su versión para padres y niños tiene el mismo modelo de cinco factores de estrés: Fantasía y miedos, Conflicto con pares, Conflicto con hermanos, Estrés escolar y Conflicto con los padres. Conclusiones: La Escala de Estrés Diario Preescolar es válida y fiable y puede ser útil tanto para fines clínicos como de investigación.

Palabras clave

Evaluación, Preescolares, Estrés cotidiano, Padres

Keywords

Assessment, Preschoolers, Daily stress, Parents

Cite this article as: Rodríguez, M. T. M., Godínez, E. R., & Ginez, O. S. (2024). Preschoolers Daily Stress Scale, Parent’s Version. Clínica y Salud, 35(3), 127 - 134. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2024a18

Funding: This publication was funding by UNAM DGAPA PAPIIT IA301521 “Everyday stress, coping and psychopathology in Preschoolers” and TA300323 “Coping-based intervention for internalized and externalized problems in children aged 4 to 6 years” of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA), Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica (PAPIIT).

Correspondence: teremonjaras87@gmail.com (M. T. Monjarás).

Daily stress refers to daily and frustrating environmental demands that can have a significant relevance on health due to their cumulative impact (Kanner et al., 1981), the latter depending on an individual’s perception of his or her life. In addition, Zarit et al. (2014) refer that daily or daily stress has an immediate effect on emotional and physical functioning through the accumulation of residual effects throughout the days, leading to overload and adverse outcomes such as clinical depression, negative emotional reactivity (Parrish et al., 2011), and increased health problems. It has also been associated with family and social difficulties (Hamer et al., 2009; Van der Wal et al., 2003), bullying (Bai et al., 2017) , and may also have an impact on increased C-reactive protein, as well as inflammatory responses across the lifespan (Gouin et al., 2012) and cortisol levels (Slatcher & Robles, 2012). Childhood adversity may predispose individuals with high neurobiological sensitivity to use maladaptive coping strategies (Hagan et al., 2017). It has been found that children with adverse childhood situations tend to report more stressful events throughout later life, which has been associated with depression in adulthood (Arpawong et al., 2022). Wu et al. (2021) suggest that daily stressors predict behavioral problems moderated by gender and age. Both family functioning and classroom environment moderated the relationship between daily stressors and conduct problems. Family functioning and favorable classroom environments may help reduce conduct problems (Wu et al., 2021). In this regard, Burkhart et al. (2017) note that most empirical work examining stress in children focus on significant life events such as parental divorce, and very few studies consider the role of daily stressors or routine day-to-day challenges whereas some of them concentrate on daily stress in children who are ill, disabled, or facing significant risks. While these findings are based on retrospective reports or parent or teacher reports of stressors experienced by children, few examine the role of stress on mood and health. Those authors conducted a study exploring daily experiences of stress, moods, and health symptoms over five consecutive days in 25 children. They categorized daily stressors into:

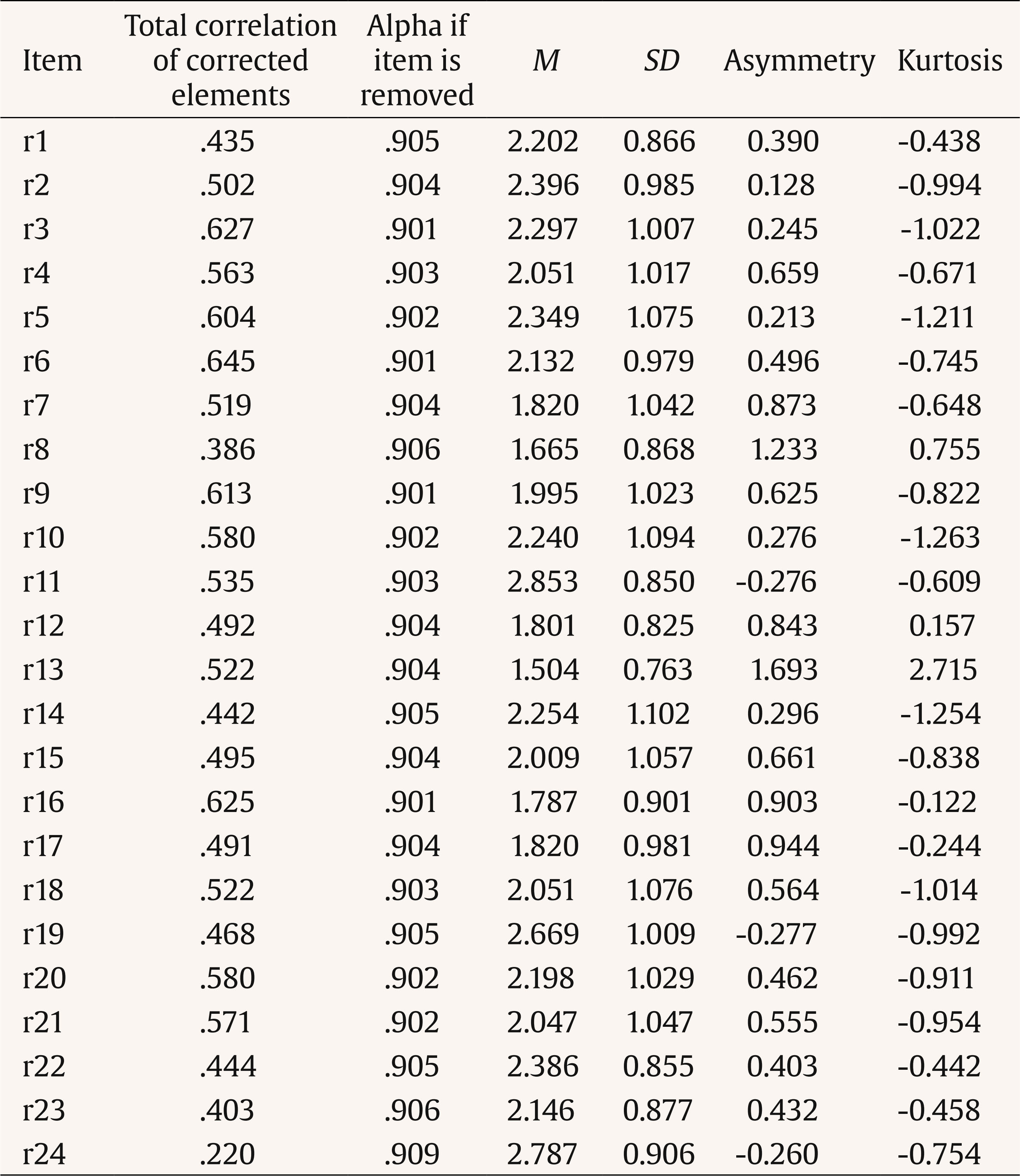

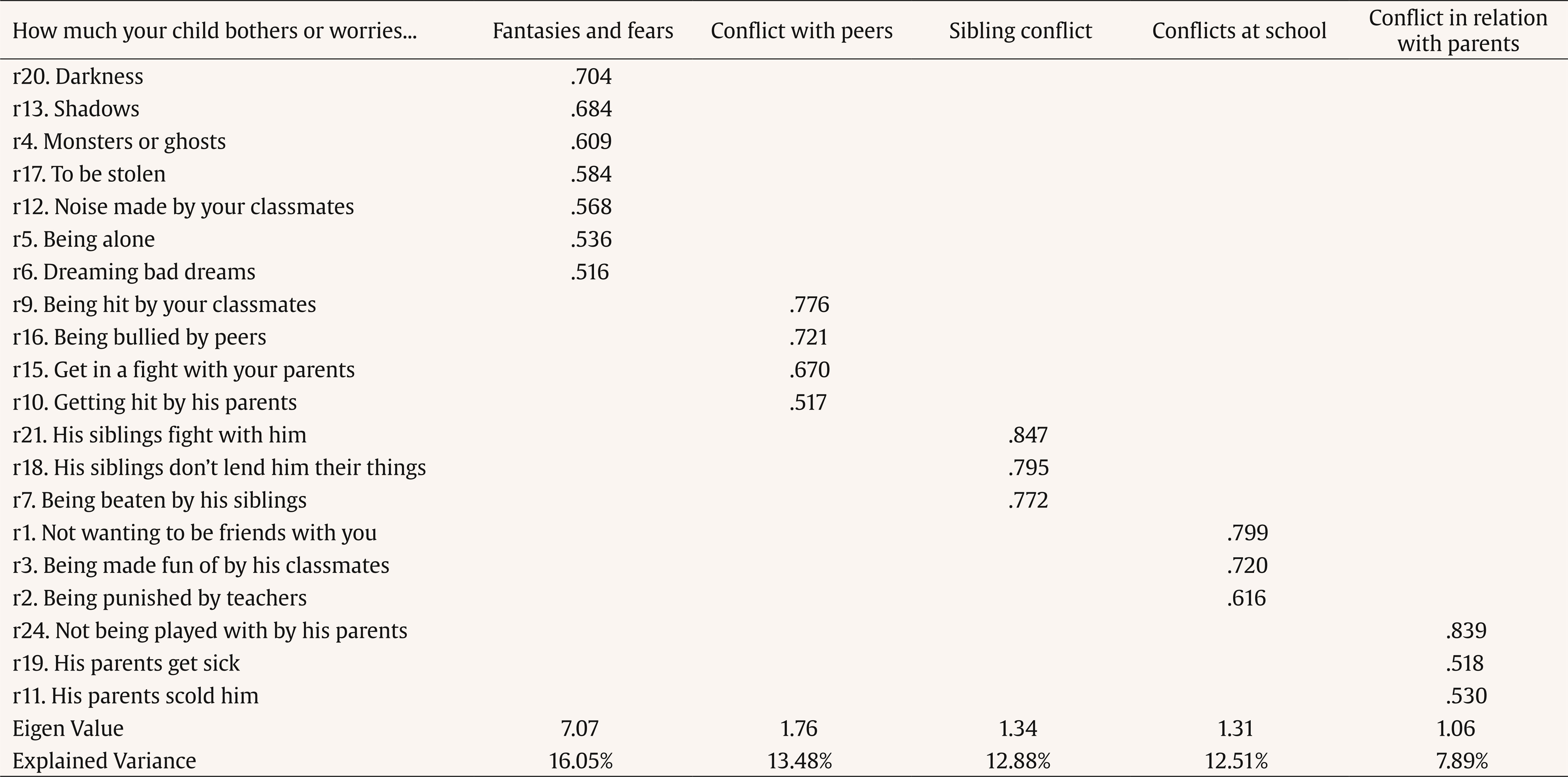

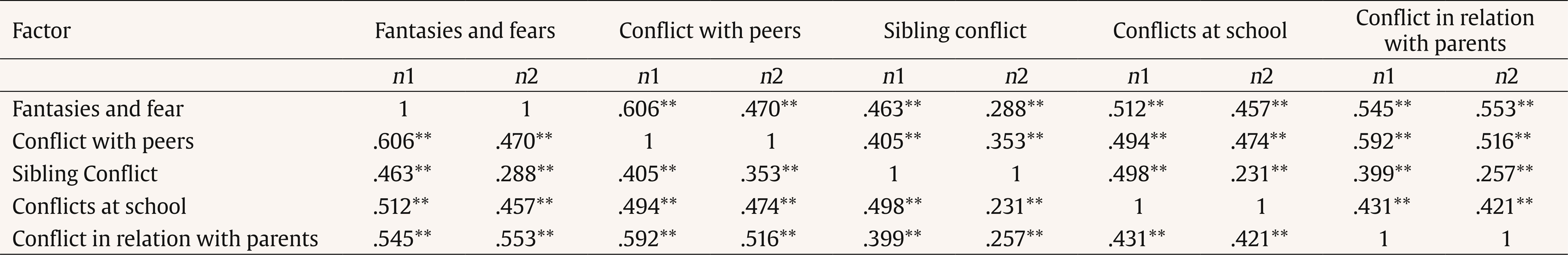

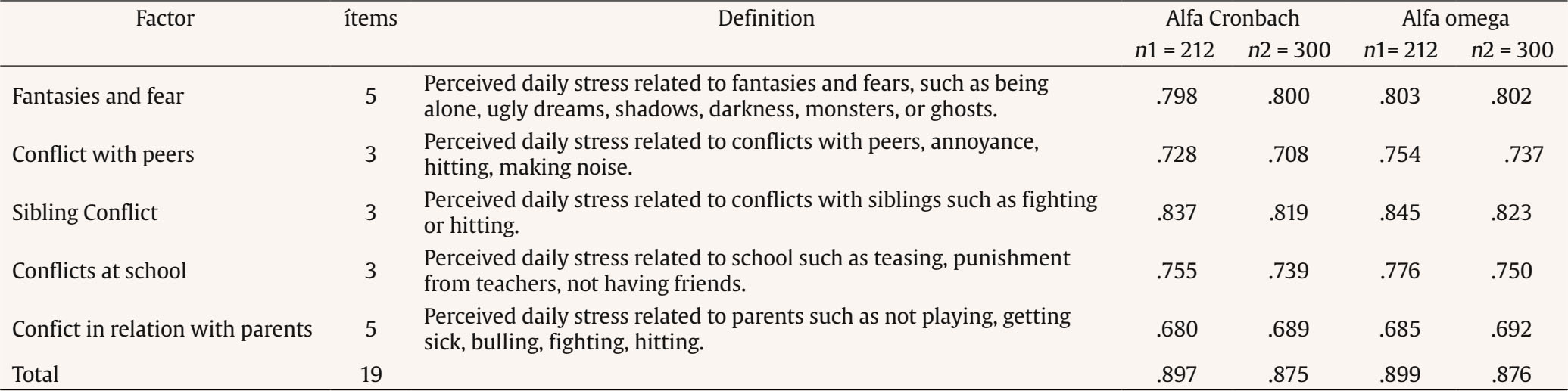

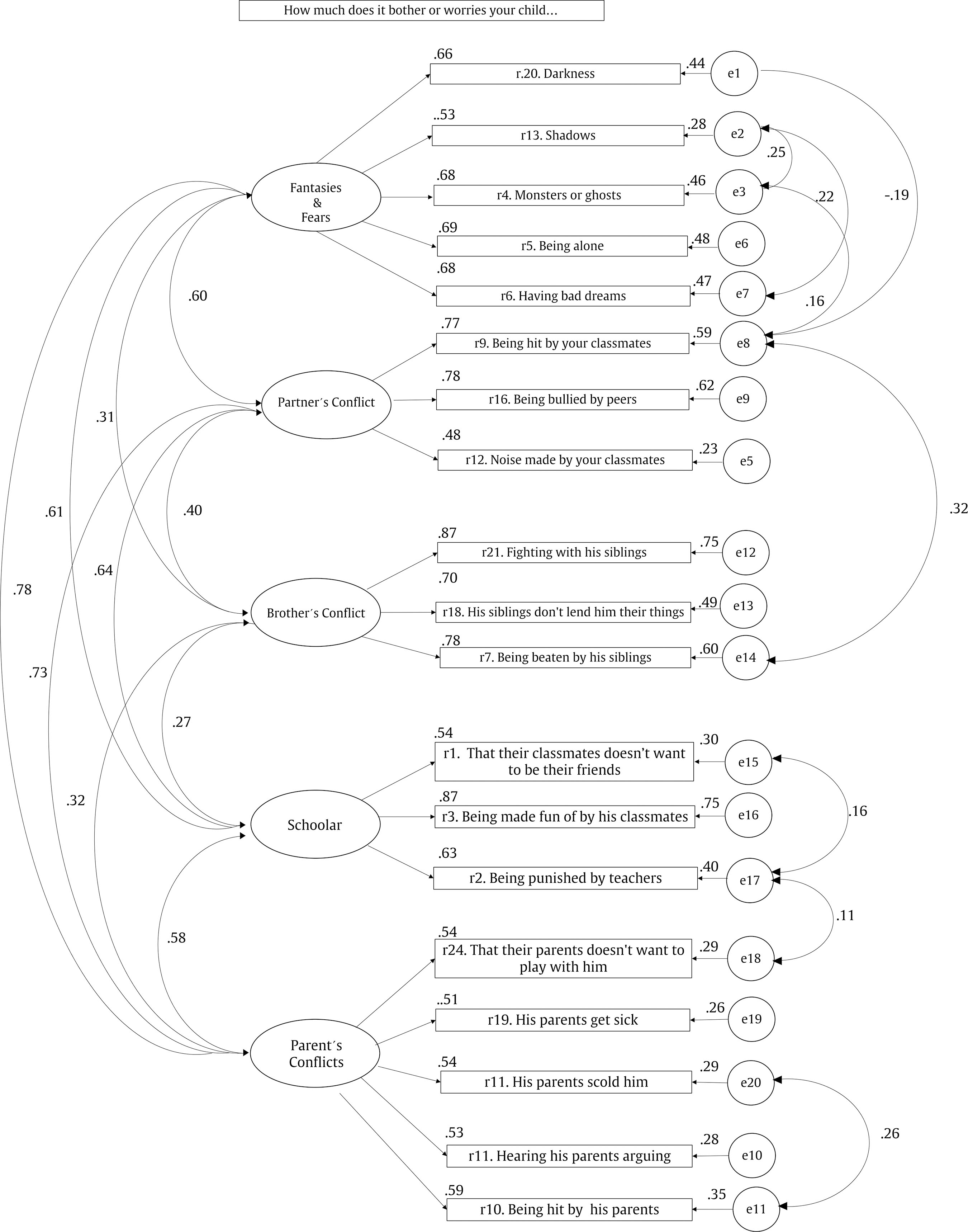

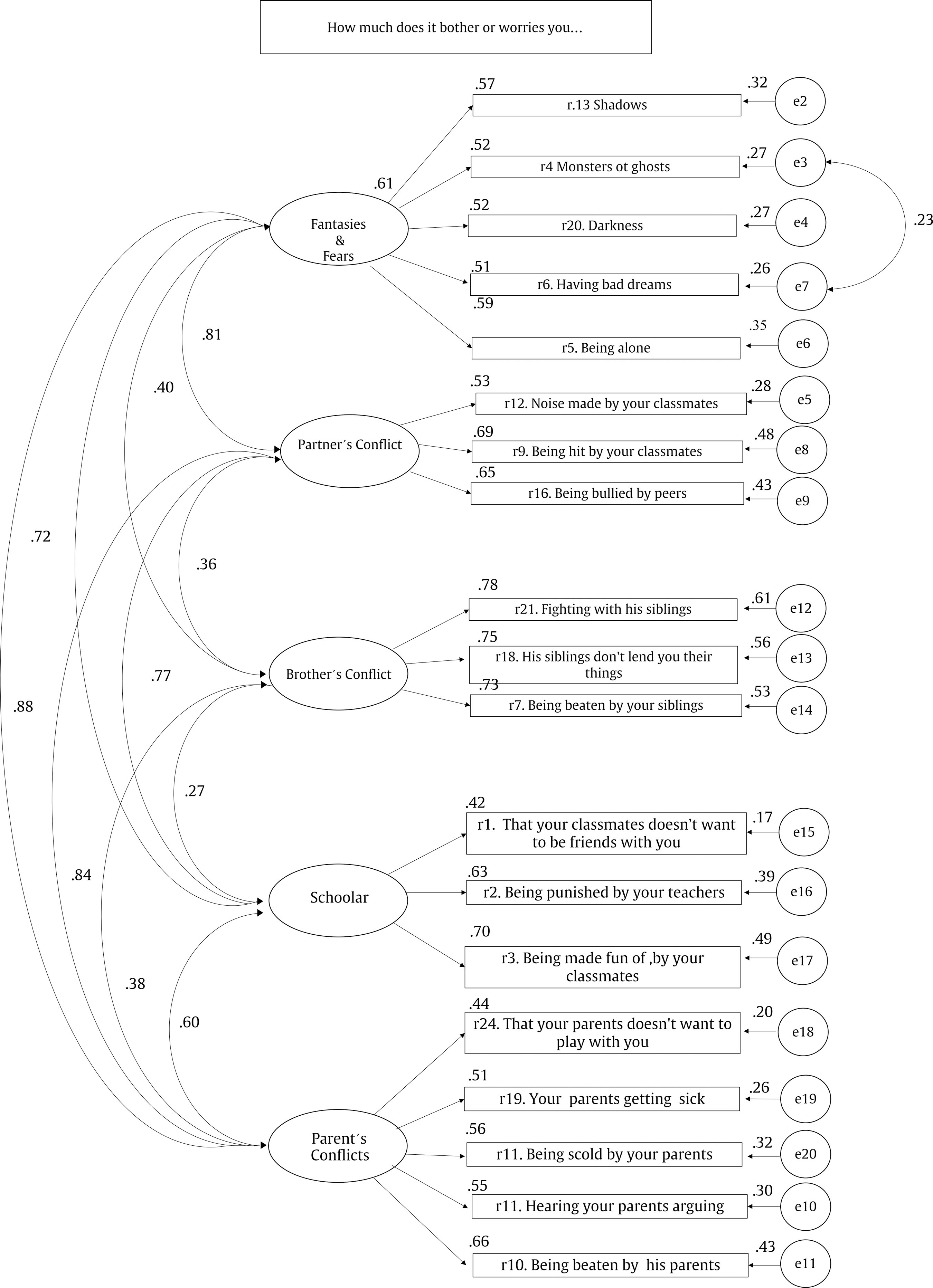

The most common stressors in the children were performance-related, control-related, and interpersonal factors. The stressful events that children reported over the five days were related to the number of aches and pains, low energy, and feeling tired. Cold symptoms were positively correlated with perceived stress control. Interpersonal stressors were positively correlated with negative mood. In addition, Slatcher and Robles (2012) found that daily conflicts at home may be critical in the relationship between stress and healthy development in young children, concluding that daily conflicts in preschoolers predict less healthy daytime cortisol rhythms. Finally, Frydenberg (2017) refers as the main areas of stress in preschoolers’ uncertainty, fear of abandonment, sadness at not having friends, fear of not having friends, and fear of being punished by parents. Some scales to measure children’s daily stress used in Latin America are the Inventory of Daily Stressors for Children aged 8 to 12 years (Trianes et al., 2009) with three factors: health, school, and family. The Children’s Stress Scale (Lucio et al., 2020) has eight factors: lack of family acceptance, verbal aggression and teasing, lack of trust and respect, school pressure, family demands, scolding and punishment, family conflicts, and fears. The Daily Stress Scale in Scholars in Chile (Encina Agurto and Ávila Muñoz, 2015) has three factors: academic stress, relational violence stress, and environmental stress. In the Mexican preschool population, there is the Daily Stress Scale in preschoolers (Monjarás Rodríguez & Lucio Gómez Maqueo, 2018), which has six dimensions in the first exploratory factorial analysis: stress in the relationship with parents, in the relationship with siblings, environmental, school, associated with fantasies, and due to punishments; said scale is pictorial and is answered by preschoolers (Cronbach’s alpha = .848). Most studies on stressors in children have also relied on parent and/or teacher reports of stressors experienced by children, although research has shown that children can identify daily events and activities that are stressful and distress or upset them (Muldoon, 2003). To plan interventions aimed at reducing daily stress, which in turn reduces behavioral problems, it is necessary to evaluate the main areas of daily stress in children, specifically in preschoolers, where research is scarce. For this reason, it is considered that for the evaluation of child behavior it is essential to have multiple informants and not only with the children’s report (Sarmento-Henrique et al., 2016); it is for this reason that the aim of this research was to obtain the psychometric properties the Daily Stress Scale in Preschoolers, version for parents, and also to get the confirmatory model of the children’s version. Participants Before conducting the pilot study, the wording of the items was modified so that they could be answered by the parents, then 20 parents answered the instrument to evaluate whether they understood the wording of the items, the modifications were made based on the comments made by the parents, and then the pilot test was conducted. In the pilot test, the Daily Stress Scale in Preschoolers, parent version, was applied to 212 caregivers of preschool children from 2 years 11 months to 6 years of age who were studying in a public school in Mexico City and the metropolitan area. Regarding preschoolers’ data, 48.6% were boys and 51.4% were girls. Mean age was 4.2 years (SD = 0.746). Nine percent were aged 2 years 9 months to 2 years 11 months, 15.6% were aged 3 years 11 months and 45.8% from 4 to 4 years 11 months, 36.8% from 5 to 5 years 11 months, and 45.8% from 4 to 4 years 11 months, 0.9% from 6 to 6 years 11 months. Regarding caregivers, 92.5% were mothers, 6.6% were fathers, 0.5% were aunts, and 0.5% were grandmothers. For the confirmatory factor analysis, the scale was applied to 300 preschool caregivers, whose ages ranged from 3 to 6 years, with a mean age of 4.66 years (SD = 0.783), 8.3% were 3 to 3 years 11 months old, 28.3% were 4 to 4 years 11 months old, 52.3% were 5 to 11 months, and 11% were 6 years old, 11 months, 49.7% were boys, and 50.3% were girls. Of the caregivers who responded to the scale, 89.7% were mothers, 6.3% fathers, 0.7% grandmother, 1.3% uncle(aunt), 0.7% foster mother, and 0.3% did not respond. The confirmatory factor analysis of the Daily Stress Scale in Preschoolers, children’s version, was applied to 397 preschoolers, of whom 25.4% reported being 4 years old, 55.9% 5 years old, and 18.6% 6 years old; 46.6% were boys and 53.4% girls. For criterion validity, the scale was applied to 187 parents; 92% were mothers, 6.4% were fathers, 1.1% were grandmothers, and .5% were adoptive mothers. Of the preschoolers, 48.1% were boys, according to the parents’ report, and 51.9% were girls, 7.5% were 3 years old, 31% were 4 years old, 48.7% were 5 years old, and 12.8% 6 years old. Instrument The Daily Stress in Preschoolers Scale (Monjarás Rodríguez & Lucio Gómez Maqueo, 2018) is a picture scale with images that evaluates the perception of children regarding daily stress in preschoolers; it is a Likert-type scale with three response options ranging from 1 (not at all) to 3 (very much), has six factors that explain 57.89% of the variance and KMO = .847, with a Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of .848. The areas evaluated are stress in the relationship with parents, stress in the relationship with siblings, environmental stress, school stress, fantasies, and punishments. The redaction of the items on this scale was changed to the parents’ version; for example, item 1, “How worried are you that your peers don’t want to be your friends?”, changed to “How worried is your child that his or her peers don’t want to be his or her friends?” and the response options changed to a scale from 1(not at all) to 4 (very much). The parents’ version does not include images. CBCL (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) applies to to 5 years old: 99 items that evaluate externalized and internalized problems. Seven items assess stress in children exposed to traumatic situations called Stress Problems for Children (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2010), items like: cannot concentrate, cannot pay attention for a long time, nausea, feeling sick, stomach aches (no medical cause), nervous or tense, sudden changes in mood or feelings. Using a Likert scale with three response options (0 = not true, 1 = sometimes true, 2 = very true or very often), it is answered by parents or caregivers. The average reliability in 24 countries was .59, according to Rescorla et al. (2011). Procedure We approached the Preschool Sector Coordination to gain access to public preschools and the directors of some private schools in Mexico City and the metropolitan area. Confidentiality of the data and the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki in 2013 were followed. The present project had the authorization of the DGAPA PAPIIT Committee IA301521. For the pilot and confirmatory study of the scale in the parents’ version, a link containing the informed consent was sent to the survey monkey. To confirm the model for the children’s version, their parents sent the informed consent. It was applied to the children during the COVID-19 pandemic, so the application was individual by Zoom. An adult was asked to connect the child to the session and then withdrew so that the child could answer by him/herself. Data Analyses Once the data were obtained, we worked with SPSS v 25 and AMOS V22 and proceeded to the corresponding analyses. The objective of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was to test the construct validity of the instrument. The maximum likelihood estimator and the following goodness-of-fit statistics were used: chi-square (c2) and adjusted chi-square c2/df), comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (NFI), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Validation and Exploratory Factor Analysis of the Daily Stress Scale in Preschoolers, Parents’ Version Item Discrimination When the discrimination of the items was performed with Student’s t-test for extreme groups, it was observed that all the items had a discrimination > 0.05, that is, they discriminated between the high score and the low score. Descriptive Analysis of the Items Table 1 shows a descriptive analysis of the items, like media, standard deviation, kurtosis, and asymmetry. Exploratory Factor Analysis To identify the first factorial structure of the variables, an exploratory factor analysis was performed, in which a coefficient of KMO = .886 was obtained, and varimax rotation was used, from which the following items were eliminated: 8, 14, 22, and 23 because they presented theoretical inconsistency with the factor. With a total of 20 items, a five-factor solution was obtained (see Table 2). With a total explained variance of 62.83%. Confirmatory Factorial Analysis The confirmatory factor analysis has a structure of 19 items, with five factors (Figure 1), and presents fit indices considered adequate. From the goodness-of-fit coefficients of the measurement model, the model is considered to have an optimal fit (CFI = .950, TLI = .937, IFI = .951), the value obtained in the RMSEA is considered acceptable (RMSEA = .048) (Kenny et al., 2015). The c2 was 226.52 and c2/df of 1.60. The five-factor structure was confirmed: Stress in relation to fantasies and fears, Stress in relation to conflict with peers, School stress, and Stress in the relationship with parents. Reliability Table 3 shows the correlation between the exploratory and confirmatory sample factors with the 19 items. Table 4 shows Cronbach alfa and omega of each factor. Validity of Criteria A Pearson correlation was performed between the Stress Problems for Children of CBCL and Preschoolers Daily Stress Scale parent´s version, which was significant with p = .000; the correlation was .305, which was moderate. Confirmatory Factorial Analysis Daily Stress Scale Children’s Version Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed with the SPSS AMOS v.22 statistical package, using the same estimators and statistics used for the confirmatory analysis of the scale. As with the latter, a structure of 19 items was obtained, with five factors. Concerning the CFA goodness-of-fit statistics, these are close to 1, so it is considered that the model adjusts to a five-factor structure, as in the version for parents. The indices were NFI = .866, IFI = .930, TLI = .914, CFI = .929, c2 =274.17, c2/df =1.994 (Figure 2). The present study had the purpose of adapting the scale of daily stress in preschoolers (Monjarás Rodríguez & Lucio Gomez Maqueo, 2018) to the version for parents, considering that in the evaluation of child behavior it is essential to have multiple informants and not only the report of the children (Sarmento et al., 2016); having the report of both the child and the parents contributes to knowing the perception of the latter and their children concerning stress in the preschool stage. In this regard different investigations have been seen where parents or caregivers tend to over-report their children’s problems, highlighting that communication, relationship between them, and difficulties in parenting can influence this (Davidson, 2005; Dell, 2014; Vann, 2018). For the clinical psychologist, it is essential to understand both the parent’s and the child’s perceptions and analyze the factors involved in the discrepancy or agreement to propose a treatment plan. Considering the above, the aforementioned scale was adapted, obtaining five stress factors, as in the confirmatory factor analysis of the version for children. The first factor is related to stress due to fantasies and fears, such as fear of the dark, ugly dreams, ghosts, etc. In this regard, it is important to say that at this stage this is often a stress factor, and it has also been seen that these fears and fantasies are directly related to the development of cognition and beliefs that are socially transmitted (Coelho et al., 2021). The second factor refers to the stress associated with conflict with peers, for example, being hit or bullied by their peers. At this stage, they begin to acquire socialization skills and sometimes may have difficulties in setting limits; if these difficulties are not identified, children could be targets of harassment by other children (bullying), which has been seen to have consequences at the psychological level in the self-concept, being this devalued, in addition to impacting the motivation and learning of children (Morales-Ramírez & Villalobos-Cordero, 2017). The third factor is related to sibling conflict, and studies indicate that behavior problems of older children have a significant negative relationship with the quality of the relationship between siblings. In comparison, behavior problems in younger children have a positive relationship with family stress (Merino & Martínez-Pampliega, 2020). One of the variables associated with sibling conflict is the personality and temperament of both siblings, insecure attachment, and parental differences in the treatment and discipline of one of the children (Dunn, 2002). The fourth factor is related to conflicts at school, mainly punishment by their teachers, not having friends and being teased. Some studies highlight that the main stressors concerning school in students aged 13 to 14 years are teachers’ attitudes towards students, described as abusive, conflicts with classmates, meetings between parents and teachers, and evaluations (Piekarska, 2000). In preschoolers, stressors are stress from punishment or teacher scolding, not feeling included in a group, and being teased seems to stand out the most. The fifth factor is conflict in relation to parents, being scolded, hit, and seeing them fight, which is related to what Slatcher and Robles (2012) mentioned, who state that daily conflict in the home increases stress and is related to physical, emotional, and behavioral health problems. Unlike the scales reported in schoolchildren where the main areas of stress are lack of family acceptance, verbal aggression, and teasing, lack of trust and respect, school pressure, family demands, scolding and punishment, family conflicts and fears (Lucio et al., 2020), in preschoolers we only found five factors. Continuing with the above, knowing the areas of stress in Mexican preschoolers provides important data to establish intervention guideline. It is important to highlight that in other research with schoolchildren stressors related to school, violence, and family conflicts have been associated with somatic complaints in children, who in turn are associated with internalized and externalized problems (Hart et al., 2013). In Mexican preschoolers, the main areas of daily stress are fantasies and fears, conflict with peers, conflict with siblings, conflict at school, and conflict in the relationship with parents, the above contrasting with what was mentioned by Frydenberg (2017), who reports as main areas of stress uncertainty, fear of abandonment, sadness at not having friends, fear of not having friends, fear of being punished by parents; it seems that in Mexico children from 3 to 6 years of age are immersed in daily stressors, related to violence and conflict, which may be associated with the country’s current context. There are few studies on daily stress scales in preschoolers. There are some in children from 8 to 12 years old, some areas match with the reports of preschoolers, for example, fears, verbal aggression and teasing, school stress, family conflicts, violence (Encina Agurto & Ávila Muñoz, 2015; Lucio et al., 2020; Trianes et al., 2009), but a difference is that preschoolers report stress related to fantasies that are linked to their developmental stage. That is why it is important to evaluate variables, such as daily stress, at each developmental stage since the experience of a 4-year-old is not the same as that of a 9-year-old. Among the limitations found in the present study, there is a lack of convergent and divergent reliability, which is suggested to be done in other studies, as well as to contrast the validity of the scale in different countries. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Monjarás Rodríguez, M. T., Romero Godínez, E., & Salvador Ginez, O. (2024). Preschoolers Daily Stress Scale, parents’ version. Clínica y Salud, 35(3), 127-134. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2024a18 Funding: This publication was funding by UNAM DGAPA PAPIIT IA301521 “Everyday stress, coping and psychopathology in Preschoolers” and TA300323 “Coping-based intervention for internalized and externalized problems in children aged 4 to 6 years” of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA), Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica (PAPIIT). Highlights - The validation of the Everyday Stress Scale for preschoolers, in its version for parents and children, is original, because early childhood is a stage in which mental health problems can be prevented in the future, being able to identify everyday stress from the perception of children and their parents, can support the implementation of workshops for the prevention of everyday stress in early childhood. - The Daily Stress Scale for preschoolers uses images that favor children’s understanding and responses, and is a useful instrument for children to express whether stressful daily situations have occurred to them and how much it stresses them. References |

Cite this article as: Rodríguez, M. T. M., Godínez, E. R., & Ginez, O. S. (2024). Preschoolers Daily Stress Scale, Parent’s Version. Clínica y Salud, 35(3), 127 - 134. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2024a18

Funding: This publication was funding by UNAM DGAPA PAPIIT IA301521 “Everyday stress, coping and psychopathology in Preschoolers” and TA300323 “Coping-based intervention for internalized and externalized problems in children aged 4 to 6 years” of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA), Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica (PAPIIT).

Correspondence: teremonjaras87@gmail.com (M. T. Monjarás).

Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS