An Integrated Analysis of the Impact of Spanish Family Support Programmes with Informed Evidence

[Un análisis integrado del impacto de los programas españoles de apoyo familiar basados en la evidencia]

Carmen Orte1, Javier Pérez-Padilla2, 3, Jesús Maya4, Lidia Sánchez-Prieto1, Joan Amer1, Sofía Baena4, 5, Bárbara Lorence3, and 5

1Universidad Islas Baleares, Palma de Mallorca, Spain; 2Universidad de Ja├ęn, Ja├ęn, Spain; 3Research Group HUM604, University of Huelva, Huelva, Spain; 4Universidad Loyola Andaluc├şa, Spain; 5Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2022a7

Received 7 March 2022, Accepted 5 July 2022

Abstract

A description is made of the quality of Spanish family support programmes, based on their impact, dissemination, scaling up in communities, and sustainability; 57 implemented programmes with informed evidence were selected by EurofamNet. Most of the programmes were shown to make a positive impact, using quantitative methodologies, and they were manualized, while about half of them defined the core contents and included professional training. From a cluster analysis of programmes with scaling up, those with a high and moderate level of systematization were identified, based on the existence of defined core contents, implementation conditions, institutional support, professional training, and reports of findings. The highly systematized programmes were characterized by a greater use of mixed methodologies, their scientific dissemination through different means, and their inclusion in services. A programme quality analysis is proposed, taking an integrated approach that relates the programme’s impact with its design, implementation, and evaluation of sustainability.

Resumen

En este trabajo se presenta una descripción de la calidad de los programas españoles de apoyo a las familias, basándose en su impacto, difusión, diseminación institucional y sostenibilidad. En el marco de EurofamNet se seleccionaron 57 programas implementados con evidencia fundamentada. La mayoría de los programas mostraron un impacto positivo utilizando metodologías cuantitativas y estaban manualizados, mientras que cerca de la mitad de ellos definían los contenidos clave e incluían la formación de los profesionales. A partir de un análisis de conglomerados se identificaron los que tenían un nivel de sistematización alto y moderado, definidos los contenidos clave y las condiciones de implementación, apoyo institucional, formación profesional e informes de resultados. Los programas con alto nivel de sistematización se caracterizaron por un mayor uso de metodologías mixtas, su difusión científica a través de diferentes medios y su inclusión en las instituciones. Se propone un análisis de la calidad de los programas, con un enfoque integrado que relacione el impacto del programa con su diseño, implementación y la evaluación de la sostenibilidad.

Palabras clave

Educaci├│n familiar, Programas basados en la evidencia, Patr├│n de calidad, Eficacia, Diseminaci├│n, Sistematizaci├│nKeywords

Family education, Evidence-based programmes, Quality standards, Programme effectiveness, Scaling-up, Program systematizationCite this article as: Orte, C., Pérez-Padilla, J., Maya, J., Sánchez-Prieto, L., Amer, J., Baena, S., & Lorence, B. (2023). An Integrated Analysis of the Impact of Spanish Family Support Programmes with Informed Evidence. Psicolog├şa Educativa, 29(1), 45 - 53. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2022a7

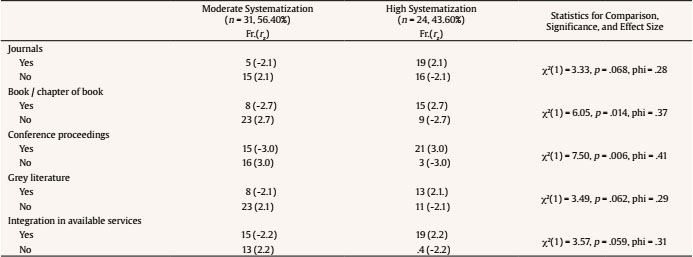

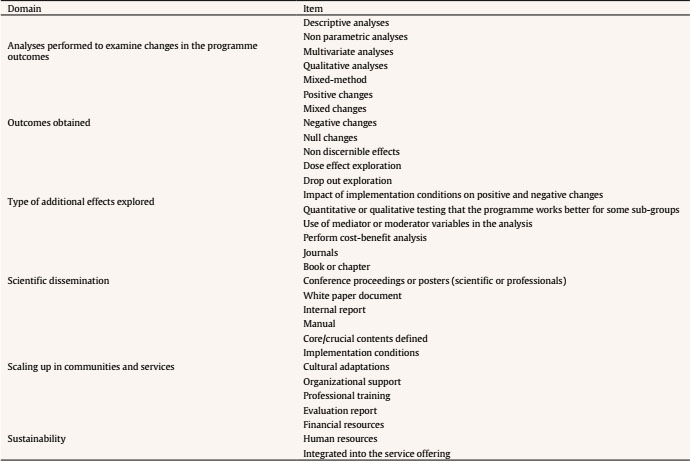

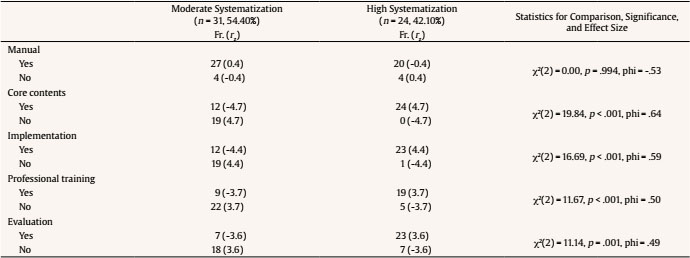

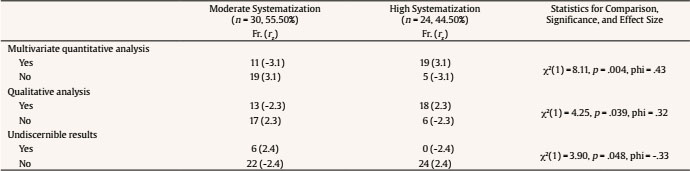

Correspondence: jppadill@ujaen.esF ((J. P├ęrez Padilla).The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child acknowledges the right of all children and adolescents to have their developmental and educational needs met in order to ensure their proper development, and suggests the preservation and improvement of family environments as a fundamental factor in achieving this goal (United Nations General Assembly, 1989). Family support is a social priority for governmental bodies in most European countries. High numbers of widely assorted family interventions can be found aimed at improving family functioning, although they all share one common goal: to foster parenting skills through a positive, strengthening, preventive approach (Daly, 2015; Dolan et al., 2006; Jeong, Pitchik et al., 2021). Responsible positive parenting calls for a broad set of parenting skills in order to foster child and adolescent development. Given the Council of Europe’s awareness that these skills are not always developed without formal support (Daly et al., 2015), it urges member states to promote them in accordance with European recommendations (Council of Europe Conference of Ministers Responsible for Family Affairs, 2006). Spain is specifically deemed to be one of the European countries that provides the strongest backup for the promotion of positive parenting (Rodrigo et al., 2022). Lots of structured family interventions can currently be found that share the same goal of promoting the well-being of children, adolescents, and their families, but there are differences in the degree to which they meet the quality standards of evidence-based practice (Hidalgo et al., 2018; Lorence et al., 2018). The European Family Support Network (EurofamNet) has developed a position statement on quality standards conceived to act as a guide in the development of high-quality family support programmes. In this statement, the emphasis is placed on how important it is for interventions to meet the needs of populations and for them to be feasible, ethical, inclusive, respectful, and sustainable through their inclusion in available services (Özdemir et al., 2021). Furthermore, it also stresses the need to take into account the different quality criteria on which the different phases of the development, implementation, and evaluation of evidence-based programmes should be based (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC, 2015]). Evidence of Impacts in Family Support Programmes Programme quality is reported in terms of the impact they make, among other aspects. An impact evaluation measures changes directly attributable to an intervention. It is considered to be one of the gold standards of interventions and not only does it serve to ascertain the extent to which goals have been achieved, but it also makes it possible to verify and improve the quality, efficiency, and effectiveness of interventions. Hence, impact evidence is a strong basis for continuing, diversifying and extending assessed interventions, and a good pretext for reconsidering the budget at the disposal of the associated service and for facilitating the said intervention’s dissemination and sustainability (Gertler et al., 2017). Impact outcomes should be assessed in an evaluation process that is rigorous, useful, feasible, adequate, and responsibly conducted (Jiménez & Hidalgo, 2016; Yarbrough et al., 2011). The best evaluation strategies are based on an external assessment process, with some kind of comparative group and follow-up evaluations in the mid-term at least (Flay et al., 2005). Of all the possible research designs, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are considered to be the most reliable in determining the quality of impacts, since they minimize the risk of estimations being influenced by extraneous factors (Moher et al., 2010). Indeed, the scientific literature review that was conducted for this paper highlighted the fact that systematic reviews mainly include impact studies based on RCT evaluations (e.g., Barlow et al., 2016; Jeong, Franchett et al., 2021; MacArthur et al., 2018). Along with the research design, it is interesting to analyse outcomes by the type of data that is used (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed), since this data is based on different statistical procedures. Experts recommend mixed methodologies, because they provide a more comprehensive insight into the evaluation process (Creswell, 2014), although there is a clear preference for quantitative methods in comparison with the other methods (e.g., Smith et al., 2020). In the literature, impact analyses of interventions tend to be defined in terms of outcomes. We found a wide variety of outcomes for RCT and quasi-experimental studies, generally presented in terms of the type of effect (positive, null, or negative) and appearance time (the short, mid, or long term). Review studies show greater evidence of positive effects than null or negative findings (Flynn et al., 2015; Jeong, Pitchik et al., 2021). There is also evidence that the impact of an intervention might tend to be moderated or mediated by the characteristics of the target population (e.g., Lagdon et al., 2021; Rubio-Hernández et al., 2020), the implementation (e.g., Li et al., 2021; Wright et al., 2017), or the evaluation (e.g., Knerr et al., 2013; Ttofi & Farrington, 2011; Vlahovicova et al., 2017). Specifically, the characteristics of implementations are a key factor in understanding a programme’s success (Jeong, Franchett, et al., 2021; Mettert et al., 2020). There is evidence of programmes whose effectiveness has been questioned due to an inadequate implementation (Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Fixsen et al., 2005). This poses such a serious potential problem that there is a bid to promote hybrid effectiveness-implementation designs so as to encourage an analysis of effectiveness and implementation outcomes within the same study (Landes et al., 2019). As for the evaluation process, studies report better outcomes in terms of effectiveness when the interventions are based on guidelines set by international bodies specializing in the recognition of evidence-based family interventions. Despite the high number of published results on the effectiveness of interventions, several review studies question the quality of the evidence. In the majority of cases, following a rigorous analysis of the risk of a methodological bias, the results are referred to as being inconclusive (e.g., Peacock-Chambers et al., 2017). Aspects relating to quality criteria are highlighted, such as the size of the sample, the use of a control group, the reliability and validity of the instruments, replicability, follow-up measures, and weak statistical significance (e.g., Gilligan et al., 2019; MacArthur et al.,2018). For instance, the analysis by Wilson et al. (2012) of the Triple P programme questions the effectiveness of Triple P for the whole population and in the long term due to the high risk of bias detected in its methodology, deficient reports, and possible conflicts of interest. Consequently, reported evidence of the positive impact of an intervention, based on RCT (with a control group), is not a sufficient guarantee of evidence-based practice. To guarantee robust findings on the impact of interventions and to be able to generalize them, rigorous risk of bias evaluations must be conducted (Matvienko-Sikar et al., 2021; Moher et al., 2010). Scaling up in Communities and Services in Family Support Programmes Once the effectiveness of an intervention has been demonstrated through strong evidence, from which firm conclusions can be drawn on what works and under what conditions it can best be given, it is important to make sure that it can be easily implemented, disseminated, and evaluated with fidelity in different environments (Flay et al., 2005). As a result, the challenge is not just to count on effective family support interventions but to make them scalable. One of the objectives of evidence-based practice is to extend the use of these interventions in an appropriate way so that a high number of families can benefit from them. To be able to scale up an intervention in communities and services, an awareness of a wide range of factors that might influence the quality and sustainability of implementations is needed, in addition to the impact it makes. It depends on a combination of the characteristics of the implementation, the organization in charge of running the intervention, and any external support (social, economic and political) involved in the scaling up process (Fixsen et al., 2005). To date, few rigorous evaluations have been conducted that take into account a joint analysis of all the scaling-up factors in studies of effectiveness (Spoth et al., 2013). With the exception of the general characteristics of implementations, which are widely described in review studies (e.g., Gilligan et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021; Park, 2021), few results are reported on aspects relating to the institutional and external support that is required to boost the effectiveness of implementations. This leads to a current dilemma on the scientific dissemination of evidence-based programmes. Although evidence from evaluations can be found that complies with the recommended quality standards needed to prove the effectiveness of interventions, a lack of available information on scaling-up components hinders the interventions’ adoption by new services (Pinheiro-Carozzo et al., 2021). As for the characteristics of implementations, before an intervention is scaled up it must comply with standards relating to materials, training, and technical support (Flay et al., 2005; Gottfredson et al., 2015). The said materials must be easily available, in addition to meeting the necessary conditions for implementations of the intervention to be evidence based. For this purpose, a good manual is recommended, where the basic features of the intervention are outlined in a clear, systematized, well-structured way (Carroll & Rounsaville, 2008; Gottfredson et al., 2015; UNODC, 2015). For international bodies like Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development, manualization is deemed to be fundamental in the scaling up of an intervention. To guarantee the effectiveness of a new application, it is important to define the core programme components (i.e., components deemed to be essential in the achievement of envisaged outcomes) not subject to modification or elimination (Flay et al., 2005; Gottfredson et al., 2015). According to Berkel et al (2011), core components are key factors in the success of an implementation and are normally reflected in the manual. This contributes to the fidelity of an intervention’s replication through compliance with aspects that should demonstrate its effectiveness. The core components of an intervention encompass a wide variety of contents (e.g., communication, rules, involvement) and processes (e.g., homework, methodology, setup, supervision). If they are shown to play an essential role in the effectiveness of an intervention, they must be clearly defined (Hill & Owens, 2013). In this respect, Jackson et al (2016) highlight how important it is for programmes to concentrate on boosting protective factors, such as communication and parenting practices. Rodrigo (2016) suggests that the core contents of programmes involve a wide range of factors that should be taken into consideration in parenting programmes: family-school collaboration, motivation, coping strategies in the event of stressful events, and family rules, among others. In family-focused practices, other authors identify educational practices, family communication, and family functioning as core contents (Lagdon et al., 2021; Marston et al., 2016). Despite the available evidence, systematic reviews over the last decade do not shed any conclusive light on the subject of core contents. To scale up an intervention in communities and services, it is important to have an organized training programme for the professionals who run it (Orte, Sánchez-Prieto, Montaño et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2020). Interventions aimed at boosting parenting skills are often given by instructors not involved in their design. Hence a set of skills, abilities, and knowledge (Forehand et al., 2010; Sánchez-Prieto et al., 2021) and a professional training programme are essential in guaranteeing high-quality implementations (Borntrager et al., 2009; Small et al., 2009). In line with evidence-based approaches, this professional training must be aimed at providing instructors with the necessary skills to guarantee the intervention’s fidelity to the fundamental characteristics of its design (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Orte, Sánchez-Prieto, Montaño et al., 2021; Orte, Sánchez-Prieto, Pascual et al., 2021; Turner et al., 2011). In addition, another quality standard is also contemplated in the application of family support programmes: the inclusion of supervisory sessions during the implementation process (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Lochman et al., 2009). The fulfilment of these conditions has been demonstrated to be related to the impact of interventions (e.g., Park, 2021; Peacock-Chambers et al., 2017). According to Fixsen et al. (2005), the external support (social, economic, and political) that an intervention receives is an important factor in scaling up, for instance, institutional commitment and support contributes to the viability of programmes (De Melo & Alarcão, 2012). Financial and technical support are needed to guarantee family access to evidence-based programmes to ensure fidelity in the continuance of the service and to optimize the success of an intervention (Rodrigo et al., 2012). Institutional support contributes to higher family participation rates, thanks to the incorporation of strategies to facilitate family attendance and motivation (a playroom, aid for travel, continuity by the same professional etc.) (Orte et al., 2016). Few studies report on the costs associated with the dissemination of interventions or, by extension, estimations of scaling-up costs (Lagdon et al., 2021). Thus, although institutional support is fundamental in gathering evidence about a programme, this data is not included in reviews of studies. In short, the sustainability of an intervention is not only dependent on impact-related outcomes, but on other additional factors that play an important role in the scaling up process in communities and services. Only in situations in which these factors are taken into account is it recommendable to contemplate the final quality criterion of evidence-based programmes: their incorporation by services (Jiménez & Hidalgo, 2016; UNODC, 2015, 2020). Current Study: An Integrated Analysis of Family Support Programmes Recent findings on the quality of family support programs show implications related to (1) programme impacts, in terms of the achievement of envisaged goals, using RCT designs as a quality criterion; (2) the relationship between the impact and the characteristics of the population and the implementation conditions; and (3), exceptionally, information on some instances of scaling up in communities through a manual or core contents, relating this with a characteristic of the programme. However, no studies were found that made a comprehensive holistic analysis of how the characteristics of programmes might be jointly interrelated. This “integrated analysis of interrelations in the quality criteria of programmes” is considered to be one of the current challenges in the evaluation of programmes, and would provide a better insight into the impacts of family support programmes and related evidence. This study aims to contribute to the achievement of this goal, thanks to efforts by EurofamNet in compiling information on the design, implementation, evaluation, impact, and dissemination of family support programmes currently being implemented in Spain and on their scaling up in communities and services (Rodrigo et al., 2022). Hence, it aims to analyse the quality of family support programmes with informed evidence in Spain. Likewise, it aspires to achieve more than just a limited vision of the impact of programmes by tackling pending challenges in the analysis and understanding of evidence-based indicators. Along these lines, three specific objectives were posed: 1) to describe the quality of family support programmes based on the impact, dissemination, scaling up in communities, and sustainability of programmes; 2) to identify the level of systematization of family support programmes based on an integrated quality-standard classification system – manualization, core contents, implementation conditions, professional training, evaluation and organizational support; and 3) to relate the level of systematization with impact, dissemination, and sustainability. Research Design Theory-based documentary research was conducted, compiling data on positive parenting and/or family support programmes in Spain. Purposive non-probabilistic sampling methods were used so that a sample could be chosen to meet the objective of the study. To assess the results, a quantitative data analysis was conducted. Sample The sample was made up of 57 evidence-informed family support programmes conducted in Spain. Family support programmes aimed at tackling numerous different issues were selected, such as substance use or behaviour disorders, among others. More specifically, 45.60% were universal interventions, 61.40% were selective interventions, and 29.80% were indicated ones. They were targeted at families with children in different developmental stages, depending on the objective of the programme: 22 were aimed at early childhood, 32 were directed at mid childhood, 46 were focused on pre-adolescents, and 33 were for adolescents. As for the operating domain, most of the interventions could be applied to families (87.7% of the programmes) and/or be directed at parents (71.1% of them). Interventions that could be applied in healthcare scenarios (45.6% of the programmes) or in schools (38.5%) also predominated. All the programmes were run on a face-to-face basis (see Bernedo et al. 2022 for a more in-depth description of the programmes). The inclusion criteria for the sample selection process were as follows: a) family support programmes of over 3 sessions, b) a defined theoretical basis, and c) programmes with available results. The exclusion criteria were: a) programmes with target population being adults unrelated to parenthood and family issues, b) programmes with an undefined methodology, contents, and/or structure, and c) a failure to identify the body or institution running the programme. Whether the programme was an original one by the authors or an adaptation of an existing one was also taken into account. Instrument To collect the data, a Formative Evaluation Template (FET) was drawn up, based on the quality standards of evidence-based programmes and a consensus reached by a group of experts on the evaluation of EurofamNet programmes. The consensus on the items included in the FET was based on the following criteria: validity, precision, reliability, confidence, and coherence. The FET was made up of a total of 43 items, which incorporated four informative categories: a) a description of the programme, b) the implementation conditions, c) its evaluation, and d) the impact, dissemination, and sustainability of the programme. Specifically, this study focused on the last category (quality of the programs in terms of their impact, and dissemination and sustainability of the programmes), which includes these items: 1) type of analysis used to explore changes brought about by the programme, 2) obtained results, 3) type of additional explored effects, 4) scientific dissemination, 5) the programmes’ integration in available services and in the community, and 6) sustainability. The answers to the items on the impact, dissemination, and sustainability of the programme took a multiple-choice format. Each of the items was accompanied by an explanation to clarify the purpose of each question (Table 1). Procedure The informed-evidence programmes were identified and their data was recorded by members of the Spanish Family Support Network. This procedure was chosen since it contributed to two goals: first of all, the members were key informants (that is, they were experts with in-depth knowledge of one or more of the programmes and could provide exhaustive information on their characteristics, functioning, and implementation) and, secondly, since the network is made up of national, regional, and local bodies, access was also ensured to programmes conducted at a local level. Programmes were identified and compiled from May 2020 to April 2021. Prior to gathering the data, the members of the network were given 5 hours of online training. This was aimed at providing instruction on the quality standards of the programmes and on the data compilation and recording process so as to boost their understanding and the efficiency and accuracy of operations. To guarantee the quality of the data-gathering process, they were supervised and guided by coordinators. Likewise, a computer system was developed to assist in the compilation of the data so that the information could be unified in a general database. The data was also stored on the intranet of EurofamNet’s website. Planned Analysis of the Data To tackle the analysis of univariate and bivariate data, frequencies and percentages were used, together with Yates’ chi-squared test to observe the significance of the frequency distribution of the 2 x 2 tables, corrected standardized residuals to facilitate the interpretation of the data, and the phi coefficient to obtain the effect size. Hence, a two-step cluster analysis was conducted. The goodness of the cluster structure is considered to be weak, satisfactory, or strong, depending on the quality coefficient or silhouette coefficient (Rubio-Hurtado & Vilà-Baños, 2017). The data was processed and analyzed using the SPSS 22 software package (IBM Corp., 2011). Ethical Considerations All the experts who participated in the study took part voluntarily after signing an informed consent form in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was carried out in accordance with the European Cooperation in Science and Technology Association policy on inclusiveness and excellence, as written in the CA18123 project Memorandum of Understanding (European Cooperation in Science & Technology, 2018). Objective 1: To Describe the Quality of Family Support Programmes To achieve this first goal, a descriptive analysis was made of the type of analysis used to examine changes brought about by the programme, the results of evaluations of the programmes, the type of additional effects that were explored, the programmes’ scientific dissemination, scaling up in communities and services, and sustainability. Firstly, from an examination of the type of analysis that was chosen it was observed that, in the case of quantitative parametric analyses, on 89.50% (n = 51) of the occasions, people in charge of running the programmes used descriptive analyses to report the results of the evaluation, followed by multivariate analyses (56.10%, n = 32). On the other hand, 12.30% (n = 7) used non-parametric analyses, and 56.10% chose to analyse the data from a qualitative perspective. In terms of the achieved results of the programmes, 80.70% (n = 46) of the programmes reported positive results, while 1.80% (n = 1) considered the changes in the families to be negative; 22.80% (n = 13) reported positive and negative changes; and 8.80% (n = 5) reported no change after analysing the data. As for the additional effects that were explored, there was some variability when the effects of the intensity of the interventions were examined, since 21 of the programmes (36.80%) that reported this kind of data had conducted a relevant analysis, whereas another 21 had not (36.80%). When it came to analyses of the drop-out rate, this information was reported in 47.70% (n = 27) of the programmes, 30 programmes (71.40%) conducted an analysis of the implementation, while a cost-benefit analysis of the interventions was less frequent, since only 8 programmes reported this kind of data (14.00%). Lastly, 40.40% (n = 23) featured a moderation or mediation analysis and 38.60% (n = 22) formed sub-groups for comparative purposes. In relation to dissemination, conference proceedings were the most common way of reporting the results of their evaluation (66.70%, n = 38). The publication of the results in scientific journals was another way of making the impact of the programmes known (63.20%, n = 36), followed by internal reports (54.40%, n = 31), books or chapters of books (40.40%, n = 23), and white paper documents (36.80%, n = 21). Only 17.50% (n = 10) used other channels for disclosure purposes. Finally, in analyses of scaling-up in communities and services, 82.50% (n = 47) of the programmes were observed to have a reference manual, 63.20% (n = 36) had defined core contents, 59.60% (n = 34) were part of services offered by the agencies to which they belonged, about half the programmes (50.90%, n = 29) counted on organizational support, 59.60% (n = 34) had financial funding, and 64.90% (n = 37) had sufficient human resources at their disposal; 49.10% (n = 28) reported that the professionals who gave the programme had been specifically trained to do so. Lastly, 30 programmes had evaluation reports (52.60%) and 10.50% (n = 6) reported on cultural adaptations. Objective 2: To Identify Spanish Family Support Programmes’ Level of Systematization To meet the second goal, a two-step cluster analysis was conducted. For this purpose, the following variables were chosen: manualization, definition of core components, specification of implementation conditions, organizational support, professional training, and an explanation of the evaluation process. In accordance with the analysed data, two clusters were formed, with a “satisfactory” quality level, close to “strong”, as shown in the silhouette analysis. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for each cluster, together with an analysis based on Yates’ chi-squared test and the frequency distribution of the selected variables. Cluster 1 (“moderate level of systematization”) is characterized by a high percentage of manualized programmes and a low percentage of programmes with defined core contents, specified implementation conditions, organizational support, professional training, and reports on the results. In contrast, cluster 2 (“high level of systematization”) is characterized by a high percentage of manualized programmes, defined core contents, specified implementation conditions, organizational support, training for professionals, and reports on the results. Comparative tests showed that the two clusters shared the presence of a programme manual. Objective 3: To Relate the Family Support Programmes’ Level of Systematization with their Impact, Dissemination, and Sustainability The results point to the existence of a relationship between the clusters and the programmes’ impact, dissemination and sustainability. Firstly, as Table 3 shows, the contingency analyses revealed a significant relationship between the two groups of programmes and the type of analysis that was conducted, with a medium effect size. Quantitative multivariate analyses and qualitative analyses were used to a greater extent in programmes with a “high level of systematization”. Secondly, a significant relationship was observed between the clusters and the obtainment of undiscernible effects by the programmes, with a medium effect size, although this kind of result was reported to a lesser extent in the second group of programmes (with a “high level of systematization”). The results also point to a significant relationship between the clusters and the use of books, chapters of books or conference proceedings for disclosure purposes, with a medium effect size, along with a trend effect in the use of journals and grey literature, with a low effect size. In all cases, greater use was observed when the programmes were characterized by a “high level of systematization”. Lastly, a trend effect between the clusters and the sustainability of the programmes was identified, more specifically, in the case of the programmes’ integration in available services, with a medium effect size. This was more common among highly systematized programmes (see Table 4). Table 4 Relationship between the Clusters and the Chosen Form of Dissemination, the Sustainability of the Programmes and the Programme’s Integration in Available Services   The purpose of this paper was to review the quality of family support programmes in Spain according to impact and scaling-up. Not only does this encompass the results of evaluations, but also aspects relating to the design of the implementation (manualization, core contents, and implementation conditions), the background context (professional training and institutional support), other evaluation-related aspects (in addition to outcomes), the dissemination of the programme, and its incorporation in services (scaling up). In the case of our first objective (to describe the quality of Spanish parenting programmes), quantitative parametric analyses are used by most of the programmes, while a large number of them report data through descriptive analyses and some use multivariate analyses. Over half the programmes also analyse the data from a qualitative perspective. Systematic reviews of programmes focus on RCT quantitative analyses (e.g., Barlow et al., 2016; Jeong, Franchett et al., 2021; MacArthur et al., 2018). However, experts like Creswell (2014) recommend mixed methodological approaches (quantitative/qualitative) to achieve better insights. Hence, one good indicator of the current state of affairs is the number of Spanish programmes that also incorporate a qualitative perspective in the evaluation process. One weakness worth highlighting is the fact that training professionals is provided in under half the cases. This training is important and it should be aimed at equipping professionals with the necessary skills to guarantee a programme’s effective application with fidelity to the core contents (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Sánchez-Prieto et al., 2021). Another weakness is the failure to report more information on the causes of the programmes’ abandonment by some participants. Just under half the analysed interventions report on the drop-out rate. In addition to this information, a description of the strategy used to foster adherence to the programme should also be included. Another weakness is the low level of cost-benefit data that is reported relating to interventions. Lagdon et al. (2021) highlight the lack of available information on the financial costs of programmes, despite the fundamental importance of this data in analyses of evidence. As for the strengths, mention must be made of the high number of programmes with a manual and specified core contents. This high level of manualization can be tied in with positive impacts, since the presence of a manual is an important factor in successful programmes (Carroll & Rounsaville, 2008). To achieve the second objective, the programmes’ level of systematization is described, based on different quality standards associated with the programmes’ core contents, implementation conditions, professional training, and institutional support. Relatively low information had been reported on these standards, as stated in, e.g., Flynn, (2015), Jackson et al. (2016), or Smith et al. (2020). A cluster analysis was conducted, leading to the obtainment of two groups: a cluster named “moderate systematization” and another entitled “high systematization”. Firstly, the “high systematization” cluster contains a higher percentage of programmes with defined core contents. This is a key element of a programme, determining aspects that are fundamental in the achievement of positive outcomes (Jackson et al., 2016; Lagdon et al., 2021; Rodrigo, 2016). Secondly, this same cluster is characterized by more detailed information on the implementation. The background context of implementations can vary, influencing the validation of programmes. Hence, it is essential to outline the implementation conditions and any adaptations that are made. In studies that analyse implementation conditions, the impact of a programme is often related to its intensity or duration (Arnason et al., 2020; Park, 2021). Thirdly, the “high systematization” programmes are characterized by a higher percentage of institutional support. This support is fundamental in facilitating the application of programmes and contributes to greater participation by families (Wright et al., 2017). Fourthly, in keeping with the findings of Flay et al. (2005), more highly systematized programmes report greater information on the evaluation process. Furthermore, this same cluster reports fewer null findings. Lastly, it also contains a higher percentage of trained professionals, which is an important factor, as we remarked in relation to the first objective, guaranteeing greater fidelity in the application of programmes (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Sánchez-Prieto et al., 2021). No differences were found in the two clusters’ level of manualization, although a quality analysis of the manuals is needed, following the approach suggested by Carroll and Rousanville (2008). Manualization is a basic ingredient: the presence of a manual ensures that important aspects of an intervention are described (such as its underlying theory, theory of change, methodology, and thematic contents) (Gottfredson et al., 2015; Sexton et al., 2011). A manual also facilitates the application and evaluation of a programme and its replication and sustainability (Jiménez & Hidalgo, 2016). With the exception of the high level of manualization found in both clusters, among the analysed Spanish family support programmes, special note must be made of the two different levels of systematization and the two rates of compliance with quality standards. This made it possible to identify the key aspects that must be improved upon in programmes in the “moderate systematization” cluster, aspects which are all essential in improving the quality of impacts. To overcome the limitations of recent research, this study strove to contextualize the impacts by taking an integrated approach to the quality of programmes. As a result, the third objective was to find interrelations between the family support programmes’ level of systematization and salient characteristics of their impact, dissemination, and sustainability. Exploring links between the level of systematization and the above characteristics is important, since evidence of an impact is the basis for continuing and disseminating an application and for promoting its sustainability (Gertler et al., 2017). In the state of the art, there was a greater presence of quantitative analyses (e.g., Smith et al., 2020). In our study, it was found that the highly systematized cluster uses multivariate analyses and qualitative analyses more often than the other cluster to determine the impact of a programme. The higher use of a qualitative perspective and, hence, a mixed methodology by the highly systematized cluster seems to confirm the recommendation by Creswell (2014) on the use of mixed methodologies. This result is aligned with further plural and less experimentalist methodological approaches in the evaluations of psycho-social interventions (Fives et al., 2017). As for the programmes’ dissemination, the results point to wider use of publications by the highly systematized cluster. This cluster coincides with the recent international trend toward greater scientific literature on parenting programmes, according to Rubio-Hernández et al. (2021). Furthermore, according to Rodrigo (2016), one quality indicator of parenting programmes is the specification of their core contents. Programmes with more detailed information on their contents are probably cited in more publications. Along the same lines, it is important to make the professionals who give these programmes more aware of the importance of disseminating the procedures involved in implementations and their outcomes. These professionals can complement the contributions of external assessors, who tend to focus on impact-related outcomes. One strength of this study was the availability of a database where experts provided details of interventions. This opened up access to information that is not normally found in journals or at scientific conferences. As for sustainability, the highly systematized cluster featured more programmes that were incorporated in services, with a trend effect being identified between the clusters and the scaling-up. According to Pinheiro-Carozzo et al. (2021), one difficulty that is normally involved in scaling-up and, by extension, in sustainability is the lack of information on components relating to a programme’s incorporation in services. In the light of our findings, this difficulty does not seem to occur to the same extent in the case of highly systematized Spanish programmes. Because very few systematic reviews take a comprehensive integrated approach to the impacts of parenting programmes, one limitation of this paper is the fact that it is harder to tie in the impact-related characteristics of Spanish programmes with the state of the art in international research on the subject. As mentioned earlier, the international systematic reviews that were found are mainly focused on RCTs. In the case of Spanish programmes, there are few RCTs. To overcome this situation, as mentioned earlier, a plural methodological approach of the assessment of these interventions could contribute with rigorous evaluations. Another limitation of the study is that analyzed programs could not be representative of the whole of existing programmes in Spain, due to the fact that they were identified through academic experts. With regard to the implications of this study for public policies, the programmes’ low level of integration in community services must be highlighted even though they demonstrate that they had impact. It is important to make policy-makers and technical experts more aware of the importance of incorporating evidence-based programmes, particularly more highly systematized ones that make a positive impact. This is also a way of guaranteeing their sustainability. As for the practical implications for professionals from the social services, healthcare, and educational sectors, the study confirms the level of systematization and impact of the parenting programmes that these professionals run in Spain. It is vital for these professionals to give priority to training in programmes with positive impacts. In terms of future lines of research, a systematic review of international parenting programmes must be made that goes further than just reporting on outcome-based impacts. Secondly, a more specific review must also be made of scaling-up or integration in community services. Thirdly, a guide to best practices should be drawn up so as to foster the adoption and integration of Spanish programmes with positive impacts in community services, together with recommendations for improving the dissemination of the impact-related outcomes of these interventions. In conjunction, this paper proposes an integrated means of analysing the quality and level of systematization of programmes. To study the impacts of programmes, it takes into account possible interrelations among key aspects of the design, implementation, and evaluation process, aimed at gaining a better insight into parenting programmes. If we break down the different parts of the model, this integrated analysis highlights the need for: i) appropriate manualization and special attention to core components as basic ingredients in the design of a programme; ii) the careful alignment of the objectives, programme design, and evaluation design; iii) an evaluation design and outcome evaluation that not only incorporate RCTS, but also rigorous quantitative, qualitative, and in particular, mixed methodologies; iv) implementations that make mothers and fathers the focal point of the intervenion; and v) implementations given by trained professionals, with appropriate institutional support. All these factors are interrelated and they determine the impact that a programme makes. In turn, this impact should also be measured in terms of its relations with scaling-up in communities and services and with the dissemination of outcomes. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Orte, C., Pérez-Padilla, J., Maya, J., Sánchez-Prieto, L., Amer, J., Baena, S., & Lorence, B. (2022). An integrated analysis of the impact of Spanish family support programmes with informed evidence. Psicología Educativa, 29(1), 45-53. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2022a7 Funding: This article is based upon work from COST Action CA18123 European Family Support Network, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) www.cost.eu.) and project PID2019-105513RB-I00 “Evidence-based socio-educational intervention for family prevention of drug abuse and affective-sex education: the Family Competence Program” funded by MCIN/ AEI /10.13039/501100011033. References |

Cite this article as: Orte, C., Pérez-Padilla, J., Maya, J., Sánchez-Prieto, L., Amer, J., Baena, S., & Lorence, B. (2023). An Integrated Analysis of the Impact of Spanish Family Support Programmes with Informed Evidence. Psicolog├şa Educativa, 29(1), 45 - 53. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2022a7

Correspondence: jppadill@ujaen.esF ((J. P├ęrez Padilla).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS