The Evaluation of Family Support Programmes in Spain. An Analysis of their Quality Standards

[La evaluación de los programas de apoyo familiar en España. Un análisis de sus estándares de calidad]

Victoria Hidalgo1, Beatriz Rodríguez-Ruiz2, Francisco J. García Bacete3, Raquel A. Martínez-González2, Isabel López-Verdugo1, and Lucía Jiménez1

1Universidad de Sevilla, Spain; 2Universidad de Oviedo, Spain; 3Universitat Jaume I, Castell├│n, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2023a9

Received 9 March 2022, Accepted 11 July 2022

Abstract

Since the well-known publication of the Society for Prevention Research about standards for evidence related to research on prevention interventions, a rigorous evaluation is considered one of the main requirements for evidence-based programmes. Despite their importance, many programmes do not include evaluation designs that meet the most widely agreed quality standards. The aim of this study was to examine the evaluation processes of fifty-seven Spanish programmes identified in the context of the COST European Family Support Network. The obtained results provide a fairly positive picture of the quality of programme evaluation standards, although more designs that include a control group, follow-up evaluations assessing long-term effects, and the evaluation of child and indirect outcomes are needed. The results are discussed from a comprehensive and plural perspective of evaluation which, in addition to methodological rigor, considers the usefulness, feasibility, and ethical rigor of evaluation research.

Resumen

A partir de las propuestas de la Society for Prevention Research sobre los estándares de evidencia necesarios para las intervenciones preventivas, contar con una evaluación rigurosa se considera como uno de los principales requisitos de los programas basados en la evidencia. A pesar de su importancia, muchos programas de apoyo familiar no cuentan con diseños de evaluación que cumplan con los estándares de calidad más consensuados. El objetivo de este artículo fue analizar los procesos de evaluación de cincuenta y siete programas españoles identificados en el marco del proyecto COST European Family Support Network. Los resultados obtenidos muestran una imagen bastante positiva de los estándares de calidad que caracterizan la evaluación de los programas, aunque es necesario ampliar el número de diseños que incluyan grupos de comparación, que contemplen medidas de los efectos en el bienestar infantil y que lleven a cabo evaluaciones de seguimiento para medir los efectos a largo plazo de las intervenciones. Se analizan los resultados desde un enfoque plural de la evaluación, que además del rigor metodológico considera la necesidad de tener en cuenta la utilidad, la viabilidad y el rigor ético de las investigaciones de evaluación.

Palabras clave

Programas basados en la evidencia, Diseños de evaluación, Estándares de calidad, Parentalidad positiva, Apoyo familiarKeywords

Evidence-based programmes, Evaluation designs, Quality standards, Positive parenting, Family supportCite this article as: Hidalgo, V., Rodríguez-Ruiz, B., Bacete, F. J. G., Martínez-González, R. A., López-Verdugo, I., & Jiménez, L. (2023). The Evaluation of Family Support Programmes in Spain. An Analysis of their Quality Standards. Psicolog├şa Educativa, 29(1), 35 - 43. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2023a9

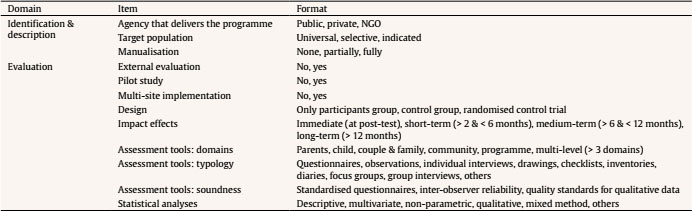

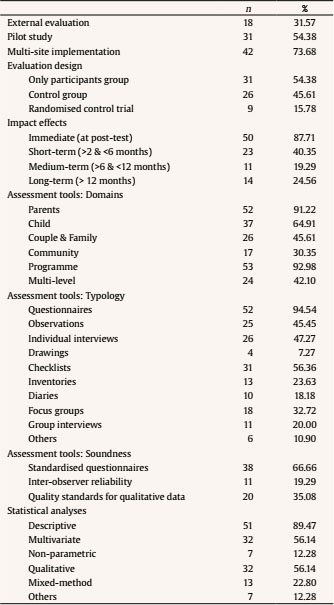

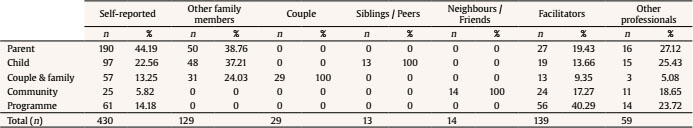

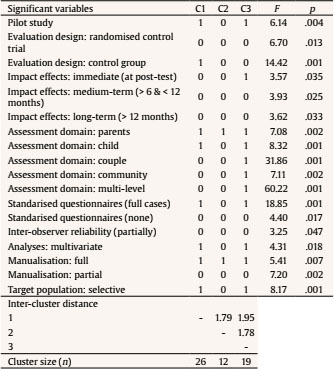

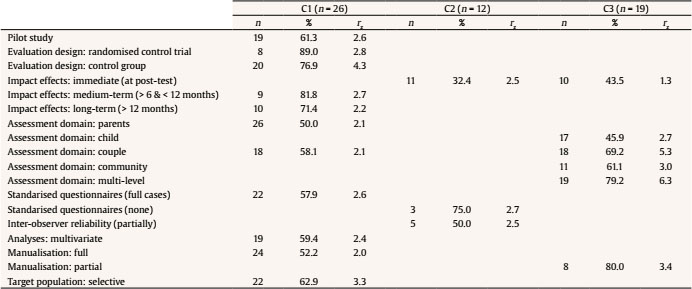

Correspondence: victoria@us.es (V. Hidalgo).Family support services aimed at guaranteeing children’s rights and well-being are currently a social and political priority for most countries, as supported by international agreements (e.g., Council of Europe, 2011, 2016; United Nations General Assembly, 1989). According to these regulations, child and family services have evolved from a traditional deficit-based model to a strengthening family support approach, with the promotion of parenting competencies and family well-being as the main purposes of the intervention (Daly et al., 2015; Davies et al., 2019). As is described in the introductory article of this Special Issue (Rodrigo et al., 2022), Spain is one of the European countries characterised by the most active endorsement of the framework emanating from the European Recommendation on policies to support positive parenting (Council of Europe, 2006). Thus, Spain shares the idea that the aim of parenting is to establish positive family relationships, which should be based on parental responsibility, guarantee the rights of children and adolescents, and promote their potential development and well-being. A positive parenting exercise implies socialisation practices based on affection, support, communication, stimulation, and structuring in routines, the establishment of limits, rules and consequences, and the accompaniment and involvement in the daily life of the children and adolescents (Council of Europe, 2006; Daly, 2007). In Spain, the incorporation of the positive parenting approach in the work with families has led to the adoption of a preventive and strengths-based approach, which recognises the institutional responsibility to support families to adequately fulfill the tasks and responsibilities related to the care and education of children and adolescents (Rodrigo et al., 2015). In accordance with national legislation, almost all local and regional governments in Spain currently have child and family services that include programmes aimed at supporting families and promoting positive parenting (Ministerio de Derechos Sociales y Agenda 2030, 2021a, 2021b). Underpinned by diverse theoretical approaches, interventions vary according to the target population, the methodology, the type of delivery, and the agencies responsible for implementation (Hidalgo et al., 2018). Although this increase in family support initiatives is a significant achievement, the current challenge is to ensure that these interventions meet internationally recognised quality standards for preventive interventions. In this sense, there is a clear consensus among politicians and researchers on the need for family support initiatives to be evidence-based, i.e., interventions that have proved to be effective through outcome evaluations, with scientific evidence showing their positive effects on families (Asmussen, 2011; Scott, 2010). Evidence-based programmes (EBP) are an efficient tool for policy makers and service-providing agencies to understand which interventions work, ensure programme effectiveness, and scale-up the best practices (Thévenon, 2020). Evidence-based family support programmes are based on theoretical models supported by scientific research; they have aims, contents, and activities structured in a manual; they have demonstrated their effectiveness; and they have identified relevant factors related to the implementation process (Asmussen, 2011; Rodrigo, 2016). Among the quality standards that characterise EBP, those related to evaluation are probably the most distinctive (Flay et al., 2005; Gottfredson et al., 2015; Small et al., 2009). Within this framework, the purpose of this study was to examine the evaluation standards accomplished by family support programmes carried out in Spain. Quality Standards Related to Programme Evaluation As was established by the Society for Prevention Research (Flay et al., 2005; Gottfredson et al., 2015), the evidence for effectiveness must come from systematic and rigorous programme evaluation, demonstrating that the programme objectives have been achieved and the intervention actually produces positive outcomes in the participants. It is considered that an EBP should have demonstrated “what works, for whom, and under what circumstances” in order to provide guarantees for its dissemination (Acquah & Thévenon, 2020). In accordance with internationally recognised quality standards related to programme evaluation, the evidence for effectiveness needs to have been demonstrated by external evaluations from multi-trial impact studies. In addition, evaluation study designs should include comparison groups and follow-up measures, preferably using randomised controlled trials (RCT) (Flay et al., 2005). In relation to programme evaluation strategies, it is considered appropriate to evaluate target outcomes (i.e., skills and behaviours that the intervention acts directly upon, in other words, the proximal effects), indirect outcomes (i.e., distal effects on family or community), and moderators (Schindler et al., 2017). In addition, the evaluation process should include the evaluation of needs, design, implementation, outcomes, and costs-benefits (Chacón et al., 2013). These complementary evaluation strategies facilitate the creation of a framework for examining not only whether a programme is effective, but also how, why, and under what conditions a programme does or does not work (Altafim et al., 2021). Finally, the programmes need to have demonstrated their effectiveness with changes in the different dimensions evaluated with a sizeable effect-size using appropriate statistical analyses and robust assessment measures (Small et al., 2009). Although the quality standards related to programme evaluation are well known, there is not much empirical evidence about the extent to which family support programmes meet these criteria. To some extent, this lack of information is due to the fact that having a rigorous evaluation design (RCT or quasi-experimental with control group) is usually an inclusion criterion in meta-analyses and systematic reviews on the effectiveness of family support programmes (e.g., Arnason et al., 2020; Jeong et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Magioni & Williams, 2016; Rayce et al., 2017; Sama-Miller et al., 2019), thus programme evaluation studies that do not meet these quality standards are not usually published in peer-reviewed journals. This fact also explains that, in the review conducted by Barlow and Coren (2018) only six systematic reviews of the effectiveness of parenting programmes published in the Campbell Library were identified. In most cases, the evaluation studies included in the reviews and meta-analyses refer to a few internationally widespread programmes (e.g., “Incredible Years” or “Triple P”) implemented in high-income countries (Asmussen et al., 2017; Barlow et al., 2016; Jeong et al., 2021). In general terms, the scarce available data indicate that rigorous evaluation processes are not at all common in the field of family intervention. Thus, the results of a recent study about family support services published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) showed that, while 85% of service providers conduct regular evaluations of their service delivery practices, only 47% perform impact assessments on child and family outcomes (Thévenon, 2020). Most providers (76%) carry out internal evaluations, which may include annual performance reviews and regular internal reporting on the number of families served. Evaluation studies to determine the impact of the interventions and the cost-benefit of the services seem to be less frequent (Acquah & Thévenon, 2020). In the same line, in a study conducted with experts from 19 European countries, 58% of the experts reported that family interventions in their countries did not comply with the criteria of EBP. Only 10% of the participating countries reported systematic evaluations of family support programmes. In most cases, evaluation processes were labelled as non-rigorous, consisting of reports on client satisfaction or coverage analyses (Jiménez et al., 2019). According to available data, quality standards less commonly met in family programme evaluations include RCT designs, follow-up measures, cost-benefit evaluations, and outcome assessment related to children’s well-being (Barlow et al., 2016; Jeong et al., 2021; Van Assen et al., 2020). The evaluation of family support programmes in Spain is very similar to the European scenario described above. Although the progressive incorporation of evidence-based practices is a reality in the field of child and family services, a significant number of family and parenting support programmes have still lack of empirical evaluations of their effectiveness (Orte et al., 2017). As was noted by Rodrigo et al. (2017), Spanish family support programmes with evidence of their effectiveness use a variety of evaluation strategies, with longitudinal and RCT designs being the least frequently used. In the same line, the study conducted by Hidalgo et al. (2018) about the quality of programmes for at-risk families in Spain showed that 75% of the programmes analysed had been evaluated, although using designs that do not meet most of the quality standards of EBP. In most cases, the evaluations were internal (65%), did not use a pre-post design to assess the impact (60%), or did not include a control group (75%). None of the programmes used RCT and only 35% performed at least one follow-up assessment (Hidalgo et al., 2018). The reasons for this situation seem clear. Evaluation studies are expensive and require expertise that many service providers (in many cases small organisations) do not have (Rodrigo et al., 2017). However, rigorous evaluations are necessary to prioritise services that have a proven impact on family outcomes (Thévenon, 2020). A Comprehensive and Pluralistic Approach to Evaluate Family Support Programmes The particularities of family intervention services help to understand the increasingly widespread consensus among researchers who state that experimental designs (dominant research paradigm for evidence of effectiveness) are not the only way to evaluate family support programmes (Canavan, 2019). In the field of child and family services, evaluation studies should respond to the interests of both researchers and practitioners (Fives et al., 2017; Yarbrough et al., 2011). As an alternative to the experimentalist perspective of programme evaluation, a pluralistic view of evaluation is emerging. This pluralistic approach emphasises the need to consider not only the methodological adequacy, but also its usefulness, feasibility, and ethical rigor in programme evaluation (e.g., Boddy et al., 2011; Fives et al., 2017; McCall, 2009; Özdemir et al., in press). Adopting a pluralistic approach on programme evaluation aims to achieve greater fit between the demands of research rigor and the real world of family intervention (European Family Support Network, 2020). From this approach, it is understood that different strategies and designs allow obtaining different kinds of information, and their value depends on their capacity to answer the questions posed in specific contexts (Fives et al., 2017). Although evidence of interventions’ outcomes is of central importance, further information is needed when the interventions are delivered in community-based settings and in a multi-agency delivery field (Almeida et al., 2022). In this sense, experimental and non-experimental designs, as well as quantitative and qualitative methods, can all be considered suitable standards if they allow answering the research questions (Proctor & Brestan-Knight, 2016). In the field of family intervention, most research questions go beyond the causal relationships between a programme and its outcomes, and address issues related to implementation, who benefits most from the intervention, and the sustainability over time. In the evaluation of family support programmes, it is as important to obtain information on internal validity as to assess external validity, evaluating, and reporting information about the ecological validity and practical relevance of programmes (Almeida et al., 2022; McCall & Green, 2004). Scope and Aims of the Study This study is part of a larger COST project entitled “The European Family Support Network: A bottom-up, evidence-based and multidisciplinary approach” (EurofamNet, code CA18123). In this project, an exercise of mapping key family support actors at the national level has been developed to create national networks that serve as foundations for a sustainable double-layered supra-national network. This supra-national network is aimed at establishing and sustaining a Europe-wide agenda for family support building down from the European level and up from the local, regional, and national level through a continuous iterative dialogue. The EurofamNet Spanish Network (ESN) is currently made up of 39 key family support actors from entities at the national, regional, and local levels in several sectors; mainly education, child welfare, and research, but also health, early years, community development, and addiction, among others. The ESN includes academics, public administration representatives and NGOs, practitioners’ associations, observatories, institutes, and ombudsmen relevant to family support in the country, according to the Spanish national representatives in EurofamNet project through a purposive sampling method (Jiménez et al., 2021). As is mentioned in the introductory article of this Special Issue, the information about the scope and quality of family prevention programmes implemented in Spain is limited. Available data seem to indicate that, although there is a clear commitment to evidence-based practices in Spain, there is still a lack of evaluation culture. The lack of detailed information on programme evaluation makes it difficult to improve future interventions and incorporate evidence-based best practices. To fill this gap, the purpose of this study was to examine the quality standards addressed in the evaluation of family support programmes implemented in Spain as identified by the ESN within the framework of the COST project. Two specific objectives were established: (1) To describe the characteristics of the evaluation standards accomplished by the identified programmes and (2) to identify typologies of family support programmes according to the quality standards. Programme Searching and Sample The programme search was based on an expert-targeted approach. Thus, ESN members were contacted for the identification of family support programmes implemented in Spain while the study was in progress (from May 2020 to April 2021). The review was by no means exhaustive but was intended to identify programmes with different quality levels of evidence. Thus, the ESN members were asked to identify family support programmes operating in their close environment and to fill in a data collection sheet for each identified programme. The information collected had to include all available data at the national level, in terms of both implementation and evaluation. For the purpose of the study, family support was understood as “a set of (service and other) activities oriented to improving family functioning and grounding child-rearing and other familial activities in a system of supportive relationships and resources (both formal and informal)” (Daly et al., 2015, p. 12). The family support programmes were selected according to a set of eligibility criteria. For their inclusion, the programmes had to meet all of the following conditions: information about the authorship (original and/or adaptations), theoretical background, more than three sessions/doses, and a written report of programme results available, as a white paper or publication. Any programme that met one of the following indicators was excluded: unidentified organisation that delivers the programme, target population being adults unrelated to parenthood and family issues, or unknown contents or/and programme methodology. As a result, 57 family support programmes implemented in Spain were identified and comprised the sample of this study. Instrument and Data Collection In order to collect the programmes’ information, a data collection sheet (DCS) was created by EurofamNet members assigned to the working package responsible for family support programmes and quality standards, in accordance with international quality standards for family support programmes described by Asmussen (2011), Flay et al. (2005), and Gottfredson et al. (2015). The first version was reviewed by four researchers with expertise in family support from different countries participating in EurofamNet. In order to provide content validity, two Spanish academic experts in the field piloted the survey and some questions were added from their feedback in the final version. A data quality assurance plan was established to avoid collection biases and guarantee the accuracy, reliability, and validity of the process. The plan included a written document with process instructions and a glossary of terms for the ESN members, as well as a five-hour training on the content and data-collection process. The DCS was created in English. Two researchers coordinated the data collection with the ESN members and a third researcher was responsible for the storage of original data files and backup on the intranet of the EurofamNet website for quality assurance purposes. The DCS included information for each programme identified with the aim of gaining insights on the quality of evidence criteria accomplished by the programmes. The obtained information referred to the programme identification, description, implementation, evaluation design, evaluation tools, and impact. This paper presents the data about the designs used for the evaluation of the programmes and the tools employed in such evaluation. As is described in Table 1, some information related to the programmes’ description was also used. Data Analysis and Reporting All the data were exported to the SPSS software package vs. 22. Descriptive analyses of frequencies and percentages were performed to report evaluation-related variables, and crosstabs were carried out to examine significant associations with programme identification and descriptive characteristics, reporting adjusted standardised residuals (rz > 1.96), Pearson’s chi square for significance (p < .05) and Cramer’s V effect size (with values V > .30 considered relevant in social sciences, according to Cohen (1988). To identify typologies of programmes based on their differential characteristics, a two-step cluster analysis was carried out, including as classification variables those identification, description, and evaluation characteristics of the programmes reported in Table 1. Firstly, a hierarchical analysis following Ward’s clustering method with standardised z-scores was performed to explore the initial setup, and the visual examination of the dendrogram, the cluster’s sizes, and the theoretical interpretation were considered (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1987). Secondly, once the number of clusters was determined, an iterative non-hierarchical k-means cluster analysis was carried out, and ANOVAs were performed to determine the significant variables that contributed to the solution. For the final solution, crosstab analyses among the clusters and those variables that contributed significantly to the solution were performed for interpretation purposes, with Pearson’s chi square as statistical significance and adjusted standardised residuals as reported values. Ethical Considerations All the experts who participated in the study took part voluntarily after signing an informed consent form in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was carried out in accordance with the European Cooperation in Science and Technology Association policy on inclusiveness and excellence, as written in the CA18123 project Memorandum of Understanding (European Cooperation in Science & Technology, 2018). Description of the Evaluation Standards Table 2 presents the frequency and percentage of the evaluation characteristics of the programmes. In approximately a third of the cases, the evaluation of the programmes was performed externally; in approximately half of the sample, at least one pilot study was carried out, and a majority of the programmes included the evaluation of multi-site implementations. Concerning the evaluation design, assessing the results only in the group of participants or including a control group was considered in around half of the sample, although random assignment to groups was used in a few cases. The impact was assessed in a large majority of the sample immediately after the programme’s completion; the short-term assessment was incorporated by slightly less than half of the sample, and a small percentage of programmes performed medium- or long-term impact evaluations. Regarding the domains of the evaluation, almost all programmes addressed issues related to parents and the programme itself. Half of the programmes analysed aspects related to children, and the couple, and nearly a third examined community issues. Analysing the typology of the assessment tools, the results indicate a wide diversity, highlighting the use of both quantitative and qualitative techniques. Regarding their robustness, standardised questionnaires were frequent in more than half of the programmes, quality standards for qualitative data in terms of saturation, transparency and generalisability were present in about more than a third of the sample, and inter-observation reliability was somewhat less frequent. Finally, the statistical analyses performed were mostly descriptive and multivariate; qualitative analyses were carried in slightly more than half of the occasions, and a smaller but relevant number of programmes used a mixed-method approach. The frequencies and percentages on the informants for each domain assessed are reported in Table 3. Regarding parent domains, self-reports predominated, followed by the professionals who delivered the intervention and other family members. Couples, siblings, peers, friends, or neighbours only provided information when specific aspects associated with them were addressed. An in-depth examination of the assessment domains was performed to explore the contents addressed in the evaluation. Regarding parent domains, issues related to parenting competencies emerged, such as their perceived efficacy as a parent (16.7%, n = 37), parenting behaviour (15.8%, n = 35), knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and values (14.4%, n = 31), and communication and conflict resolution styles (11.7%, n = 26). Other aspects linked to the personal sphere were less frequently assessed, such as mental health (4.5%, n = 10), personality (4.5%, n = 10), or attachment (4.5%, n = 10). Regarding couple and family dimensions, the topics collected included family climate (26.4%, n = 19), parenting alliance (18.1%, n = 13), affection (12.5%, n = 9), and conflict resolution (12.5%, n = 9). In relation to children and adolescents, the most frequent aspects of analysis were their behaviour, whether positive or negative (20.2%, n = 26), their emotional and social development (19.4%, n = 25), and their communication and conflict resolution skills (10.9%, n = 14). Their quality of life (7.8%, n = 10), cognitive abilities (7.8%, n = 10), and their physical and mental health status (6.2 %, n = 8) were scarcely addressed. At community level, information was obtained about the support network (39.5%, n = 17), community resources (20.9%, n = 9), and social integration (18.6%, n = 8); the least evaluated aspect was ethnicity (2.3%, n = 1). Finally, focusing on the programme itself, the most evaluated topic was satisfaction (45.4%, n = 48) and, to a lower extent, its participant responsiveness (21.3%, n = 23) and fidelity (19.4%, n = 21). After an in-depth description of the evaluation characteristics of the programmes, associations with identification and description characteristics (namely agencies responsible for implementation, target population and degree of manualisation) were performed. The only significant associations indicated that programmes addressing universal prevention included more frequently randomised control trials (66.67%, rz = 2.0) than those addressing selective or indicated population (33.33%, rz = -2.0, χ2 = 4.09, p =.043, V = .27). Moreover, fully manualised programmes included more frequently a pilot study (63.04%, rz = 2.7) in comparison with programmes that were not manualised or only partially manualised (36.96%, rz = -2.7; χ2 = 7.20, p = .007, V = .35). Typologies of Family Support Programmes A hierarchical cluster analysis identified three theoretically meaningful clusters of programmes based on their identification, description, and evaluation characteristics. A subsequent iterative non-hierarchical 3-mean cluster analysis was carried out, with squared Euclidean distance values between centres of clusters greater than 1 indicating a satisfactorily discriminating solution. Cluster sizes were adequate to perform an intergroup analysis (see Table 4). The variables that contributed significantly to the clusters are presented in Table 4. Table 5 presents frequency, percentage, and adjusted standardised residuals for the contributing variables for each cluster. The first cluster was characterised by programmes aimed mainly at selective population, with pilot studies, rigorous evaluation designs (both control group and randomised control trials), both parent- and couple-level assessments, frequent use of standardised questionnaires, medium- and long-term impact testing, and multivariate analyses. Additionally, these programmes accomplished a full manualisation, providing a detailed manual with a full description of goals, contents, activities, methodology, and ways to be implemented and evaluated, which allows a reliable application. The second cluster was characterised by programmes where no standardised questionnaires were used, reliable observation across raters were partially applied, and impact assessments were immediate. Finally, the third typology was characterised by programmes including multi-level assessments, those with children, couples and the community, immediate impact analyses, and partially detailed manuals. The aim of this study was to examine the quality standards addressed in the evaluation of family support programmes implemented in Spain. To this end, the characteristics of the evaluation processes of 57 programmes identified within the framework of the European Family Support Network were analysed. The obtained results showed that, in most cases, evaluations were internal and tested multi-site implementations of the programmes. Although more external evaluations are needed, evaluating multi-site implementations is considered a gold standard, since the fact that a programme has evidence from an evaluation conducted at one time and place does not mean that it is equally effective under other implementation conditions (Asmussen & Brim, 2018). In relation to the evaluation designs, the results showed that quasi-experimental designs with control groups were used in almost half of the evaluations, although randomised trials were used less frequently. These results are consistent with previous data on the evaluation of family support programmes in Spain and other European countries (Hidalgo et al., 2018; Thévenon, 2020), and confirm that experimental designs are not the most common methodological choice for programme evaluation in the field of child and family services (Orte et al., 2017). The fact that RCTs were used less frequently with selective and indicated target population than in universal programmes highlights the ethical difficulties of randomising in real intervention contexts with families who are experiencing difficulties (Fives at al., 2017). From the pluralistic view of programme evaluation, the lack of experimental designs should not be interpreted as low-quality evidence of the effectiveness of family support programmes (Martínez-González et al., 2016). As has been noted, different designs and methodological strategies can be considered quality standards if they allow adequately answering research questions and the demands of practitioners (Almeida et al., 2022; Proctor & Brestan-Knight, 2016). As has been defined by Gottfredson et al. (2015), effectiveness studies are those developed to determine whether a programme is effective when translated to the real world. To conduct effectiveness studies in the “real world” of child and family support services, a wide range of designs and methodological models are necessary to address the diversity of contexts within which intervention and evaluation processes are set (European Family Support Network, 2020). In the analysed programmes, impact evaluations were conducted in most cases immediately, without assessing long-term outcomes. Regarding this issue, the evidence for effectiveness does not accomplish an important quality standard. It is not considered sufficient to demonstrate positive effects at the end of the interventions; EBPs must have demonstrated long-term benefits on certain family and child outcomes (Barlow et al., 2016; Gottfredson et al., 2015). To this respect, follow-up evaluations are needed to better understand the short-, medium-, and long-term effects of parenting and family support programmes, and to inform about the design of improved interventions that can maximise and sustain initial benefits over time (Jeong et al., 2021; Özdemir, 2015). Regarding the assessed domains, the results showed that most programmes evaluated dimensions related to parents and, to a lesser extent, to children, families, and communities. As was described in the introduction, quality evidence on the effectiveness of the programmes requires evaluating both target and indirect outcomes (Schindler et al., 2017). Evidence that an intervention is effective for parents does not necessarily mean that children will also benefit from it. As has been noted by Asmussen and Brim (2018), while evidence of improved parent outcomes is a good starting point, further testing is required to verify child benefits. From an ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner, 2005), the most comprehensive evaluation should be multi-level, analysing the effects of interventions on parents and children, on the family functioning, and on the community. This multi-level evaluation was observed in almost half of the analysed programmes, which highlights the strong endorsement of ecological-systemic approach in child and family services in Spain (Rodrigo et al., 2017). With respect to the contents addressed in the evaluation, issues related to parenting competencies, parental sense of efficacy, knowledges, attitudes, beliefs, and communication and conflict resolution styles emerged as frequently assessed regarding parent domains. In relation to the couple and family dimensions, the most frequently collected topics included the family climate and parenting alliance. Finally, the most frequently analysed aspects with respect to children and adolescents were their behaviour and their emotional and social development. In all cases, the results showed that a variety of informants were used. The informants were mainly parents and professionals, giving less space to the voices of children and adolescents. These results are in agreement with those found in the most recent reviews, and they show the required fit between the objectives of the interventions and the outcomes assessed (Barlow et al., 2016; Chacón et al., 2013). The results related to the assessment tools used for the evaluations of the programmes showed a wide diversity, highlighting the use of both quantitative and qualitative techniques. These results are consistent with the pluralistic approach of programme evaluation described above (Canavan, 2019). Different tools can be considered suitable if they allow answering the proposed research questions. In fact, it is advisable to use diverse evaluation formats that include, in addition to questionnaires, observation and individual or group interviews to obtain both quantitative and qualitative information (Almeida et al., 2022). Thus, the selection of assessment tools should be based on a rights’ promotion perspective that values and considers the voice of children and families (Jiménez et al., 2021). According to quality standards of EBP, in relation to the assessment tools and the data analysis, their soundness and suitability is fundamental, offering assurance of reliability and validity for measuring the target and indirect outcomes (Small et al., 2009). In this regard, the obtained results showed that most of the standardised questionnaires used accomplished quality standards. Appropriate standards for saturation, transparency, and generalisability of qualitative data were less frequent. Regarding the statistical analyses performed, the results showed that they were mostly descriptive, with multivariate and qualitative analyses being less frequent. Overall, there is a certain diversity in the soundness of the instruments used and the analyses performed. This diversity is probably related to those responsible for carrying out the evaluation studies. As was noted above, rigorous evaluations are expensive and require expertise that not all organisations have. To address this situation, service providers should have access to the necessary funds to commission agencies for external evaluations or develop partnerships with universities to conduct research projects (Thévenon, 2020). A cluster analysis was performed to complete the analysis of evaluation processes. Three theoretically meaningful clusters of programmes based on their evaluation and design characteristics were identified. The first group found included programmes that fulfilled most of the EBP quality standards: pilot studies, full manualisation, rigorous evaluation designs (quasi-experimental and RCT), evaluation of direct and indirect outcomes, assessment of medium- and long-term effects, use of standardised questionnaires with evidence of reliability and validity, and multivariate data analyses. This group was the largest and included 26 programmes, i.e., almost half of those analysed in this study. The other two groups were composed of programmes that were not characterised by such a clear compliance with quality standards, but with differences between them. On the one hand, the third cluster was made up of 19 programmes characterised by an ecological and multi-level evaluation (including children and community outcomes), assessing immediate effects (at post-test), and having partially detailed manuals. On the other hand, the second cluster, comprising 12 programmes, had the worst quality indicators, characterised by the lack of robustness of the measurement tools used and by the fact that they only evaluate immediate effects. In sum, the results of the cluster analysis allow us to conclude that there is an increasing number of family support programmes in Spain that accomplish the main quality criteria related to the evaluation process. Likewise, among those that do not have evaluations with all the standards, some of them also present relevant quality criteria, such as multi-level evaluations. Programme evaluation is a central component in EBP, and there is a clear agreement on the need to increase the use of standards for evidence to support the development of effective programmes within family support services (Acquah & Thévenon, 2020). Overall, the results of this study provide a fairly positive picture of the quality of programme evaluation standards, and this represents an important step forward in the progressive incorporation of evidence-based practices and the improvement of family support services in Spain. According to a pluralistic methodological approach, the Spanish family support programmes address both scientific and professional practice criteria, as they adopt evaluation strategies, which makes it possible to be scientifically rigorous, but also sensitive to a specific reality and cultural context (Canavan, 2019; Fives et al., 2017; Yarbrough et al., 2011). This study has some limitations. The programmes identified do not represent all the family support programmes existing in Spain. The programme search was based on an expert-targeted approach that may have led to the sample of programmes identified as not fully representative. In addition, although a data quality assurance plan was established, the form sheets were completed by a large number of researchers, members of the ESN, which may have led to reliability biases. Finally, more information on the characteristics of programme evaluation could have been collected. Despite these limitations, this study provides a comprehensive view of family support programme evaluation in Spain. In conclusion, the characteristics of the evaluation processes described in this study show that many milestones have been reached in family support delivering in Spain, although important challenges remain. These conclusions point out several practical implications that can enhance programme evaluation in our country. Firstly, evaluation designs including control groups and follow-up evaluations of long-term effects are still needed to better understand the real effects of family support programmes as well as their benefits over time. Secondly, it is not enough to evaluate the effects of the interventions on the parents and the family system; the assessment of the impact on the child and other indirect outcomes is needed to understand the scope of the benefits of family support programmes. Thirdly, greater robustness of the measurement tools is required to ensure the quality of evaluation studies, particularly referred to qualitative and observational techniques. Overall, the results obtained in this study show that the incorporation of standards is a reality in Spain, although there is room for improving the evaluation processes in order to extend evidence-based programmes and disseminate their results among researchers, front-line pracitioners, and policymakers. Addressing the criteria of usefulness, feasibility, and ethical rigor of evaluation studies it is absolutely crucial to know what works, for whom, and under what circumstances in order to enhance family support services. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Hidalgo, V., Rodríguez-Ruiz, B., García Bacete, F. J., Martínez-González, R. A., López-Verdugo, I., & Jiménez, L. (2022). The evaluation of family support programmes in Spain. An analysis of their quality standards. Psicología Educativa, 29(1), 35-43. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2023a9 Funding: This article is based upon work from COST Action CA18123 European Family Support Network, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology). www.cost.eu. References |

Cite this article as: Hidalgo, V., Rodríguez-Ruiz, B., Bacete, F. J. G., Martínez-González, R. A., López-Verdugo, I., & Jiménez, L. (2023). The Evaluation of Family Support Programmes in Spain. An Analysis of their Quality Standards. Psicolog├şa Educativa, 29(1), 35 - 43. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2023a9

Correspondence: victoria@us.es (V. Hidalgo).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS