Impact of Coping Strategies on the Academic Satisfaction of University Students and Their Association with Socioeconomic Variables

[La influencia de las estrategias de afrontamiento en la satisfacción académica de los estudiantes universitarios y su asociación con variables socioeconómicas]

Ana Dorado Barbé1, David González Casas1, Linda V. Ducca Cisneros1, & Jesús M. Pérez Viejo2

1Complutense University of Madrid, Spain; 2National University of Distance Education, Madrid, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2024a12

Received 3 July 2023, Accepted 31 August 2024

Abstract

Conflict situations in higher education settings often lead to high stress levels among university students. Coping strategies are crucial in students’ educational experiences and academic satisfaction. This study aimed to analyse the coping strategies in conflict situations and their correlation with social and academic variables in Complutense University of Madrid (UCM) students. A study employing both qualitative and quantitative approaches, using data triangulation, was conducted through online surveys distributed to 2,803 students, along with six focus group sessions. The findings indicate that appropriate coping strategies are positively associated with academic satisfaction and mediation training. Female university students tend to use emotion-focused coping strategies more frequently, whereas students at lower academic levels tend to use avoidant coping strategies more often. Understanding and investigating the relationship between coping strategies and socio-academic variables can aid in implementing educational policies to enhance students’ personal resources and academic experiences in higher education.

Resumen

Las situaciones de conflicto en entornos de educación superior a menudo conducen a niveles elevados de estrés en los estudiantes universitarios. Las estrategias de afrontamiento son cruciales en las experiencias educativas y la satisfacción académica del alumnado. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo analizar las estrategias de afrontamiento en situaciones de conflicto y su correlación con variables sociales y académicas en los estudiantes de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM). Se llevó a cabo un estudio empleando enfoques tanto cualitativos como cuantitativos, utilizando la triangulación de datos, a través de encuestas en línea distribuidas a 2,803 estudiantes, junto con seis sesiones de grupos de discusión. Los resultados indican que las estrategias de afrontamiento adecuadas se asocian positivamente con la satisfacción académica y la formación en mediación. Las estudiantes universitarias tienden a usar estrategias de afrontamiento centradas en las emociones con mayor frecuencia, mientras que los estudiantes de niveles académicos inferiores tienden a usar estrategias de afrontamiento evitativo con más frecuencia. Comprender e investigar la relación entre las estrategias de afrontamiento y las variables socioacadémicas puede ayudar a implementar políticas educativas que mejoren los recursos personales y las experiencias académicas de los estudiantes en la educación superior.

Palabras clave

Satisfacción académica, Conflicto, Estrategias de afrontamiento, Bienestar emocional, Mediación, Estudiantes universitariosKeywords

Academic satisfaction, Conflict, Coping strategies, Emotional well-being, Mediation, University studentsCite this article as: Barbé, A. D., Casas, D. G., Cisneros, L. V. D., & Viejo, J. M. P. (2025). Impact of Coping Strategies on the Academic Satisfaction of University Students and Their Association with Socioeconomic Variables. PsicologĂa Educativa, 31(1), 1 - 10. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2024a12

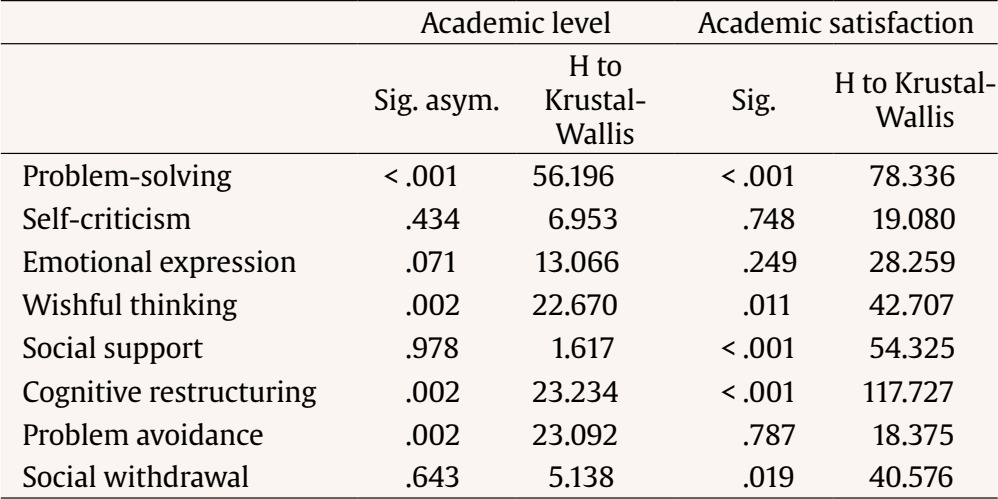

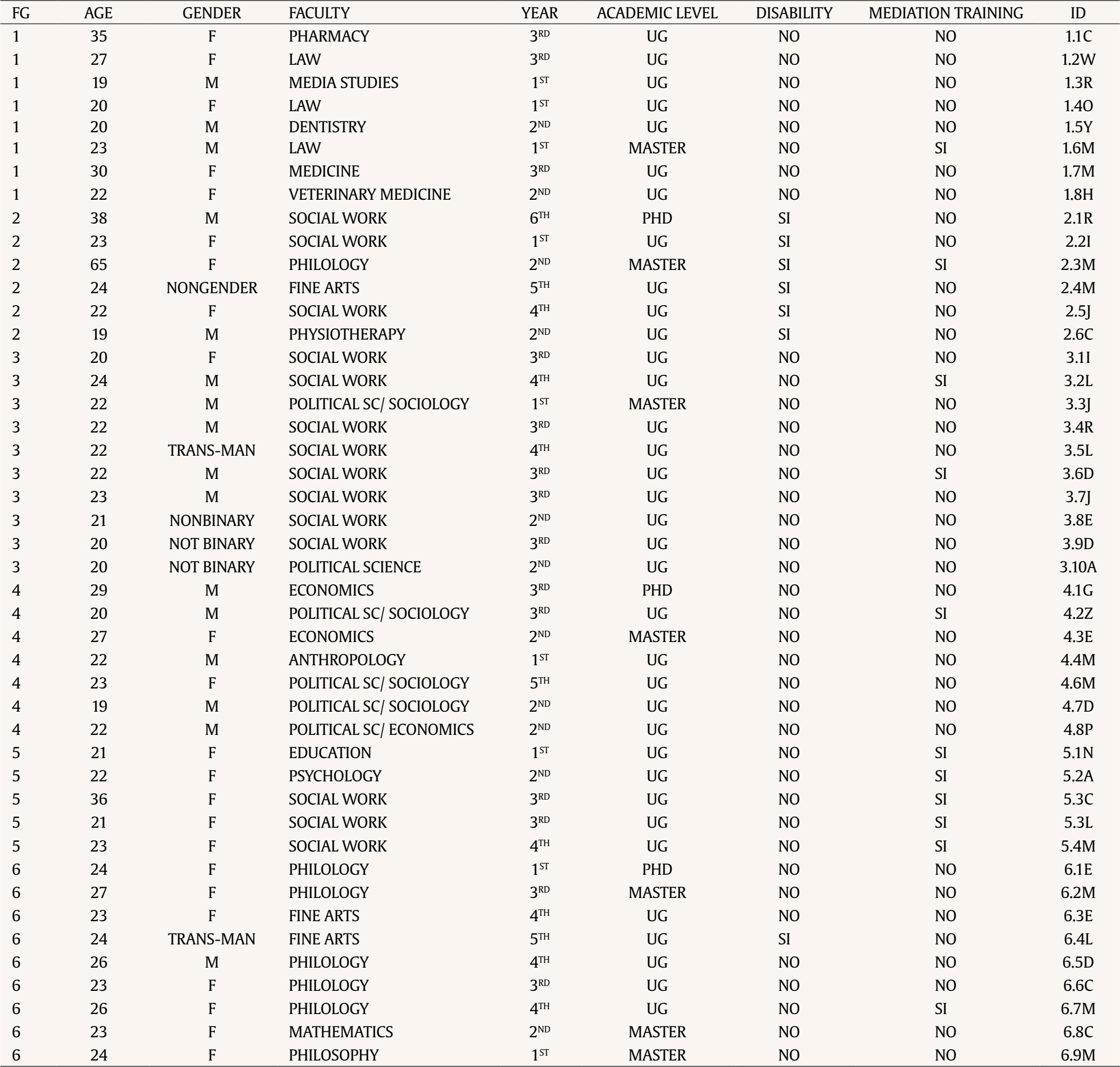

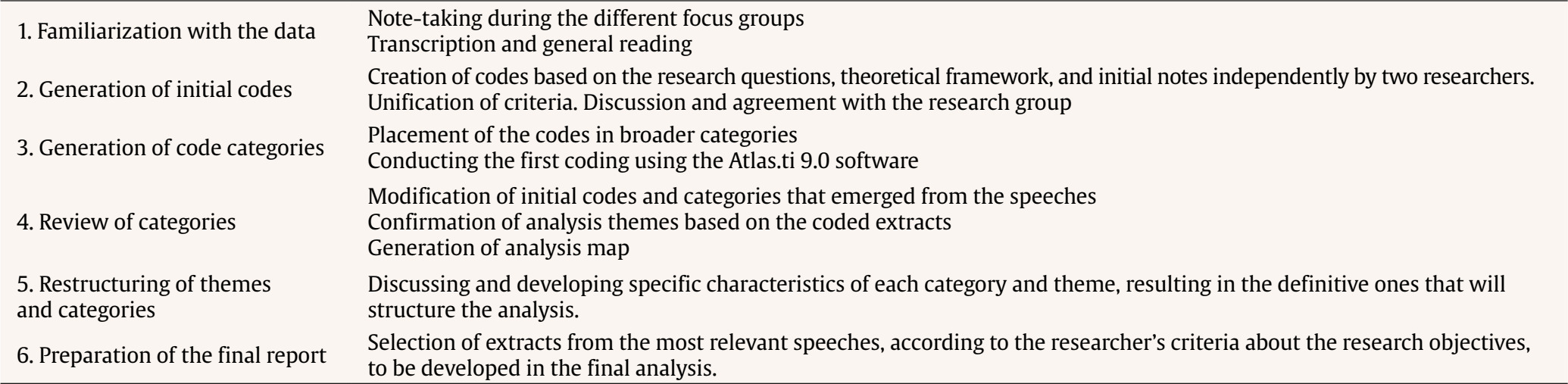

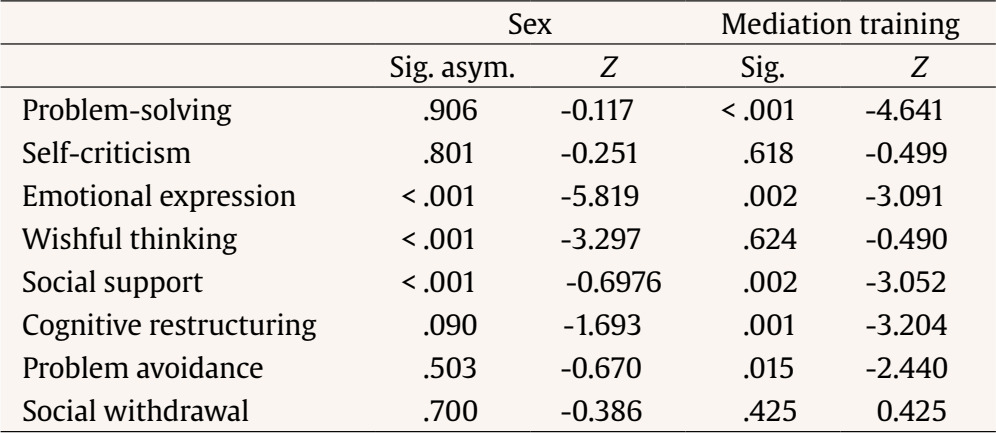

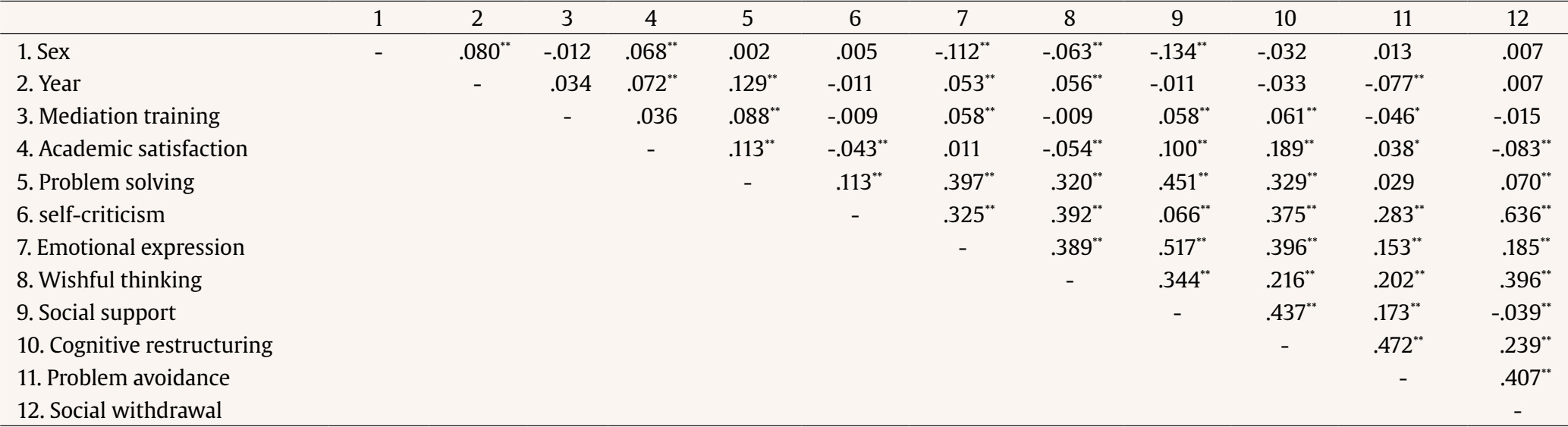

Correspondence: davgon14@ucm.es (D. González Casas).The context of higher education is regarded as a peak of academic stress because of the combination of different variables ranging from a great workload of the relevant psychosocial changes in the life cycle of the students (Beck et al., 2003; Pascoe et al. 2020) to the increase of conflicts associated with interpersonal and/or academic variables (Harrison, 2007). Furthermore, after the COVID-19 pandemic, the university has undergone significant changes in teaching and learning models. Numerous studies have shown an increase in stress in university students (González et al., 2022), with an impact on psychological well-being (Dorado-Barbé et al., 2021; Oliveira et al. 2021). Conflicts are an inevitable part of human coexistence and personal and social development (Dorado-Barbé et al., 2015), even if they generate stressful situation (Mendoza et al., 2010). Disagreements in relationships with peers or teachers are a clear destabilizing element in emotional well-being (López et al., 2021) with direct repercussions on academic success and students’ self-perception (Tharani et al., 2017). Coping is a multidimensional process with consequences on psychosocial well-being (Bello-Castillo et al., 2021). It is a dynamic, processual, complex, and stabilizing construct aimed at promoting the person’s adjustment to stressful experiential contexts (González et al., 2007). It involves cognitive and behavioural efforts aimed at seeking resources to manage internal and/or environmental situations perceived as stressful (Folkman, 1984; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). These resources aim to modify the external or internal conditions through actions to solve the problem and/or internal processes to manage emotions derived. Therefore, they constitute a key issue in the study of people’s psychosocial well-being (Farnier et al. 2021; Gustems-Carnicers & Calderón, 2013). In this sense, it is worth noting the differentiation made by Sandín (2003) between coping strategies and styles. Coping strategies consist of concrete actions taken to modify the stressor’s conditions, such as to seek social support, face the problem, resignify or avoid the situation. However, coping styles are general personal tendencies to adopt one or another coping strategy. In this regard, Morrison and Bennet (2016) point out that the use of coping strategies varies depending on the situation or context. While coping styles are not related to the context or stressor stimulus, they resemble personal traits that predispose to face a situation perceived as stressful in a certain way. According to Pelechano (2000), they are not opposing concepts but complementary ones: styles represent stable and consistent ways of coping with stress, while strategies are specific and concrete actions. Several studies have addressed the relationship between coping and psychosocial well-being. For example, Galiana et al. (2020) studied variables related to psychological well-being and quality of life or psychosocial interventions in the context of medical care or chronic patient care. Hogan et al. (2015) analysed variables in clinical psychology, such as therapeutic relationship, attachment, treatment of mental disorders, or the impact of psychological interventions. Hutchinson’s (2014) study on coping and its impact on social well-being in Mozambique includes variables related to different coping strategies, social well-being (encompassing quality of life, social connectedness, and perceived support), socioeconomic conditions, contextual circumstances, social support networks, and resilience in disadvantaged contexts. In a different direction, Rao et al. (2003) explored factors that influence access to health care, income inequality or community development in fields such as economics, public health or social policy. How people face and react towards their experienced problems has a direct impact on their overall perception of wellbeing. Thus, strategies are more relevant to the intervention perspective because of their modifiability (Labrador, 2017). Coping strategies used by students to manage conflicts are important aspects to consider (Gutiérrez et al., 2021) because they determine how destructive or constructive the conflictive interactions are experienced (Luna, 2020). Based on the importance of coping strategies in the psychosocial well-being of individuals, there are various classifications and measurement instruments applicable to psychosocial research. Classifications are based on the support required to cope with the problem independently (Litman, 2006), on the approach or avoidance of the problem (Gol & Cook, 2004), and on the orientation to solving the problem or regulating the emotional response (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980). Besides, these dimensions are not mutually exclusive since coping strategies can simultaneously include different categorizations based on their function and the context in which they are generated (Stanisławski, 2019). Tobin et al. (1989) emphasized the significance of discerning between appropriate and inappropriate coping strategies, categorizing them into four types: appropriate problem-focused and emotion-focused strategies and inappropriate problem-focused and emotion-focused strategies. The study focuses on the coping strategies used by individuals to manage stress and difficulties in their daily lives. It explores the organization of these strategies in a hierarchical model and their relationship with each other considering psychological variables such as perception of control, social support, and self-efficacy in stress management. In addition, it examines the validity of the Coping Strategies Inventory as a tool to measure these strategies in the population studied. Studies show that using appropriate problem-focused strategies is associated with better health and decreased stress (Sasaki & Yamasaki, 2007), while employing inappropriate emotion-focused strategies, such as avoidance, is linked to higher stress levels and poorer health outcomes (Fullerton et al., 2021; Pritchard et al., 2007). Concerning gender, men tend to use avoidant strategies more frequently than women (Eschenbeck et al., 2007) and women use strategies related to emotional expression and social support more frequently (Salgado & Leria, 2018). Besides, studies show that coping strategies vary throughout the life cycle (Jones et al. 2020; Meléndez et al., 2008). For example, as people get older, they move from employing problem-focused strategies to emotion-focused strategies (Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010; Meléndez et al., 2020). On another note, academic satisfaction has become a category of analysis with notable prominence in research (Franzen, 2021; Viladesbosch & Calvo, 2021). The category has been studied from the perspective of service quality and psychological well-being (Vergara-Morales et al., 2018) and in relation to students’ perception of their academic environment (Medrano & Pérez, 2010). The coping characteristics are relevant to the academic satisfaction of university students (Palomino, 2018) since the range of strategies used to cope can lead to well-differentiated consequences: a) a hurtful emotional footprint or, on the contrary, b) a constructive process that facilitates socio-personal development (Arias-Cardona & Arias-Gómez, 2017). In this sense, several authors (Lent et al. 2007; Morelli et al. 2023; Shehadeh et al. 2020) demonstrated how students with higher levels of academic satisfaction show high levels of self-perception about their abilities, perceived social support that facilitates their academic goals, and more adequate progress toward their objectives. Alternative methods of conflict resolution and, more specifically, mediation as an approach to conflict situations are established as a key competency in university study programs (Dorado & De la Fuente, 2022). Since most of the mediation training offered in Spanish universities is optional, Iglesias and Ortuño (2018) highlight the importance of mediation as a contribution to the psychosocial well-being of people in the educational environment. Analysing the personal resources of students to successfully face situations of adversity is a challenge in higher education contexts (Casullo & García, 2015; Mishra, 2020). For all of the above, the aim of this research was to analyse the coping mechanisms employed by students at Complutense University of Madrid (UCM) during conflict situations and to explore how these strategies are linked to various social and academic factors such as gender, academic level, or mediation training. The study employs both qualitative and quantitative approaches using data triangulation. It was conducted through online surveys distributed to 2,803 students, along with six focus group sessions. This research not only addresses a significant gap in the existing literature but also has practical implications for improving the academic experience and overall well-being of students at Complutense University of Madrid (UCM) and potentially beyond. Sample The participants in the quantitative study were selected through a non-probabilistic sampling of UCM students enrolled in the academic year 2021-2022. The final sample consisted of 2,803 students (71.1% female, 28.9% male), with an average age of 21.8 (SD = 2.97). Concerning the academic level, 74.7% were undergraduate students, 12% were master’s students, 1.7% were enrolled in postgraduate-specific programs, and 10.5% were doctoral students. A final question was included to recruit volunteers for the qualitative study. One hundred five individuals expressed interest in participating. The final sample consisted of 45 students. Table 1 shows the typological categories of focus group (FG) members based on the variables under study. Data Collection Techniques - A questionnaire including sociodemographic variables, such as age, gender, field of study, and academic level, was used. To conduct a more accurate analysis of the academic level variable, 8 categories were created for undergraduate students to indicate the academic year in which they were enrolled. This methodological decision is based on the research team’s interest in being able to analyse the impact of the academic year and level on the dependent variables in a more detailed manner. As indicated in the literature, first-year university students exhibit distinct characteristics, as the transition from secondary education to university can pose a challenge related to the modification of previously assigned roles and/or adaptation to new academic demands (Brougham et al., 2009). Taking this into account, the eight categories (ranges) created were: 1st year of Bachelor’s or Double Bachelor’s; 2nd year of Bachelor’s or Double Bachelor’s; 3rd year of Bachelor’s or Double Bachelor’s; 4th year of Bachelor’s or Double Bachelor’s; 5th year of Bachelor’s or Double Bachelor’s; University Master’s; Own Title; and Doctorate. The variables that follow were also included. - The students answered the Spanish adaptation of the Coping Strategies Inventory (CSI, developed by Cano-García et al. (2007), based on the original study by Tobin et al. (1989). The CSI is a self-report measure to assess people’s subjective perception of their coping strategies in response to stressful situations. The CSI consists of 40 items that are responded to on a rating scale (Likert) varying from 1 = not at all in agreement to 4 = absolutely in agreement. The CSI is structured around 8 dimensions which have a Cronbach’s alpha ranging between .72 and .94: problem-solving (5 items, e.g., “I struggled to solve the problem”), self-criticism (5 items, e.g., “I realized that I was personally responsible for my difficulties and blamed myself”), emotional expression (5 items, e.g., “I let my feelings out to reduce stress”), wishful thinking (5 items, e.g., “I wished the situation had never started”), social support (5 items, e.g., “I found someone who listened to my problem”), cognitive restructuring (5 items, e.g., “I reviewed the problem over and over in my mind and eventually saw things differently”), problem avoidance (5 items, e.g., “I did not let it affect me, I avoided thinking about it too much”), and social withdrawal (5 items, e.g., “I spent some time alone”). - To measure academic satisfaction, the Spanish adaptation of the Academic Satisfaction Scale (ESA), developed by Medrano & Pérez (2010), was chosen. The ESA is a self-report measure that assesses students’ subjective perception of their academic satisfaction. It consists of 8 items that are responded to using an ordinal scale (1 = never, 4 = always). It has a one-dimensional structure called academic satisfaction with a Cronbach’s alpha of .84 (8 items: “I am interested in the classes”, “I feel motivated by the course”, “I like my teachers”, “I like the classes”, “The course meets my expectations”, “I feel comfortable with the course”, “The teachers are open to dialogue”, and “I feel that the content of the classes corresponds to my profession”). - Also, six focus groups were held to explore experiences in an interactive environment (Hamui-Sutton & Varela-Ruiz, 2013). This collectivist research approach allows for discourse enrichment through the contributions of group members. Before the focus groups, a facilitator’s guide was designed to focus on the following topics: coping strategies, academic satisfaction, gender, disability, and mediation training. Open-ended questions facilitated the discussion about potentially relevant aspects related to the analysed variable dimensions (Gundumogula, 2020). Procedure For the completion of the study, funding and collaboration were provided by the Observatory of the Student (UCM). The research was approved by the UCM Research Ethics and Biosafety Committee (Ref. CE_20211118-11 SOC). The online questionnaire was sent to all students enrolled in the 2021-2022 academic year and was available for completion from March 25th to April 25th, 2021. The qualitative phase was conducted between May 4th and May 14th. The content of the focus groups was transcribed literally and analysed through Atlas. ti 9.0 software. Data Analysis The present research was based on a mixed explanatory sequential approach (Creswell & Clarke, 2018), with a descriptive and correlational scope and a cross-sectional design. The research was conducted in two sequential phases, a first quantitative phase and a second qualitative phase. In the interest of facilitating a better understanding of the object of study, the methodological decision led to a combined use of quantitative and qualitative research approaches (Cresswell & Clark, 2018). This combination overcomes the limitations of quantitative and qualitative methods (Turner et al, 2017). The data was analysed based on the eight dimensions of the Coping Strategies Inventory (CSI) scale. Subsequently, the information was triangulated generating an interpretative process that allowed for coherent results (Cisterna-Cabrera, 2005) from an integral perspective (Carter et al., 2014). To meet the study objectives, and concerning the quantitative data, the univariate normality of both dependent and independent variables was first assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The results indicated that the probability value (p) obtained significance levels below .05, leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis (H0), suggesting that the sample distribution was not normal. Given the non-normality of the sample distribution, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test was employed to compare the medians of the dependent quantitative variables with the two dichotomous qualitative variables (gender and mediation training), setting the significance level at p < .05. In addition to what has been mentioned, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to verify if there were statistically significant differences between the independent variables of academic level (with the corresponding extension by courses in undergraduate students) and academic satisfaction, regarding the dependent variables (coping strategies). For the categorization of the academic level variable, 8 ranges were used: 1st year of Bachelor’s or Double Bachelor’s; 2nd year of Bachelor’s or Double Bachelor’s; 3rd year of Bachelor’s or Double Bachelor’s; 4th year of Bachelor’s or Double Bachelor’s; 5th year of Bachelor’s or Double Bachelor’s; University Master’s; Own Title; and Doctorate; and for the categorization of the academic satisfaction variable, 24 ranges were used (0 = no academic satisfaction, 24 = total academic satisfaction). The significance level was set at p < .05. To check the correlation between the variables under study, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used as a non-parametric measure that assesses rank correlation. Significant correlations were observed at the .01 and .05 levels. For the analysis of qualitative data, the Atlas.ti 9.0 software was used, which has allowed the organization of data for thematic analysis (Clarke & Brown, 2013). The categories of analysis were formulated based on the specific objectives of the research, which corresponded to the different variables under study defined from the theoretical framework that guided the research. The content was assessed following inter-coder reliability to ensure consistency in coding among different analysts. The following steps were followed to process the information, as shown in Table 2. Quantitative Results The results obtained through the Mann-Whitney non-parametric test indicate significant differences in the use of emotional expression, wishful thinking, and social support strategies based on gender. The results obtained for the average ranks indicate that women use these strategies more frequently than men. Under the same statistical parameter, the results show that having received mediation training maintains statistical significance with the use of problem-solving, emotional expression, social support, cognitive restructuring, and problem-avoidance strategies. The average ranks could indicate that individuals who have received mediation training use problem-solving, emotional expression, social support, and cognitive restructuring strategies more frequently, while those who have not received such a training use the problem-avoidance strategy more frequently (Table 3). The results obtained in the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test, used to analyse whether there are relevant differences between academic level variables and academic satisfaction regarding the eight coping strategies, indicate significant differences based on the academic level in which students are enrolled and the use of problem-solving, wishful thinking, cognitive restructuring, and problem avoidance strategies. In this regard, the average ranks obtained in the analysis show that doctoral and master’s students use more frequently problem-solving, wishful thinking, and cognitive restructuring strategies, while undergraduate students in their first year tend to use problem avoidance more frequently. Regarding academic satisfaction, the results obtained through Kruskal-Wallis indicate differences in the use of problem-solving, wishful thinking, social support, cognitive restructuring, and social withdrawal strategies. The average ranks show that students with a better perception of their academic satisfaction (ranking above 18 out of 24 points) use problem-solving, social support, and cognitive restructuring strategies more frequently, while students who perceive lower levels of academic satisfaction (ranking below 12 out of 24 points) have a tendency to use wishful thinking and social withdrawal strategies more frequently (Table 4). Table 4 Krustal- Wallis of Coping Strategies as a Function of Academic Level and Academic Satisfaction   Considering the association and significance, the Spearman correlation was analysed to evaluate the degree of relationship between dimensions (Table 5). As observed, there is a significant correlation at the .01 (bilateral) level between the variable sex and emotional expression, wishful thinking, and social support dimensions. Additionally, there is a significant correlation at the bilateral .01 level between the academic level and problem-solving and problem-avoidance dimensions. Furthermore, the academic level maintains a significant correlation at the bilateral .05 level with the emotional expression and desiderative thinking dimensions. Regarding the variable of having received training in mediation, the results show a significant correlation at the bilateral .01 level with the dimensions of problem-solving, emotional expression, social support, and cognitive restructuring. In addition, the same variable presents a significant correlation at the bilateral .05 level with the problem-avoidance dimension. Finally, academic satisfaction maintains a significant correlation at the bilateral .01 level with the dimensions of problem-solving, social support, cognitive restructuring, desiderative thinking, and social withdrawal. At the bilateral .05 level, academic satisfaction maintains a correlation with the problem-avoidance dimension. Qualitative Results Qualitative results begin with the contextualization of conflict in people’s lives based on the meaning attributed by students, who consider that conflict arises when some different objectives or interests are perceived as incompatible: “Conflict is a collision between two or more ideas held by two or several people, where they have different interests and find themselves in a situation of disagreement between both”. (3.2L). “When you try to achieve something, and due to a barrier, you can’t reach it, or when two people seek different things and are not willing to compromise, in the broadest sense, that’s how I would define conflic”. (1.6M). Conflicts are perceived as inherent elements of human coexistence. Although they are sometimes seen as an opportunity, students believe their consequences can be positive or negative depending on how they are managed. “I believe that conflict is inherent in every social structure, and we experience it in our daily lives... No matter how well-organized a society is, conflict will always arise because there is always a diversity of interests”. (4.2Z). “To me, it seems like an opportunity for both parties to express their opinions and to change a situation that may cause some discomfort to one of the parties...”. (3.9D). “We have this view of loss when it comes to conflict. I often see it as a gain. That is to say, from the fruit of conflict, if managed well, many opportunities and fruitful things can arise...”. (5.3). Furthermore, conflict in university life is seen as a divergence of opinions or expectations in which power relations play a fundamental role: “I believe that there is a question of difference in expectations, and that is, in my academic experience, conflicts generally arise because teachers expect certain things, students expect others, and I expect something from my schoolmate”. (1.7M). “The general conflict with the university would be when you are trying to achieve something and you encounter a barrier, whether it’s administrative, bureaucratic, or simply a lack of interest in solving that problem”. (1.6M) “I believe that conflict is also a space or situation where we see that there are two parties involved. Normally, with the faculty, there is sometimes a power relationship. That is to say, in most of the conflicts I have seen, there is one party that is above the other...”. (4.7D). The eight dimensions of the CSI (Lazarus & Folkman, 1986) guided the analysis of results within the university. These dimensions can be grouped into broader categories: problem-focused strategies and emotion-focused strategies, and appropriate and inappropriate management. Concerning the strategies located in the adequate management of the problem, they include problem-solving and cognitive restructuring dimensions. The problem-solving strategy, i.e., cognitive and behavioural efforts aimed at eliminating stress by modifying the situation that produces it, appears clearly in the students’ discourse. It allows them to act proactively in the interest of finding solutions: “I, for example, I always try to mediate. I think that my character does not make me either avoidant or conflictual, in the sense of being the first to face up to problems...”. (1.8H). “That’s why, whenever something comes up, what I try to do is to solve it as soon as possible, but because I don’t like stress...”. (4.4M). Cognitive restructuring involves the use of cognitive strategies aimed at modifying the meaning of the conflict situation that generates stress. Students verbalise that it is commonly used, as it makes it easier for them to manage their conflicts and helps to protect their emotional well-being: “The truth is that, as life, in the end, makes you a bit conformist in that sense too, and I say: ‘Well, I’m going to try to do my best and adapt to the environment”. (4.5A). “A few years ago, I started reading about emotional intelligence and I decided that I had to become strong and when there was a conflict, I had to face the conflict and say: ‘Look, this has made me feel this way. This is my opinion. Try to communicate, which at the end of the day is what you do”. (6.2M). On the other hand, the dimensions of avoidance and desiderative thinking appear related to the strategies located in the inadequate management of problems. Avoidance as a strategy appears in a generalised way in the students with an emphasis on previous experiences: “Well, I prefer to avoid conflict. But the truth is that many times you can’t avoid it”. (2.4M). “The experience of my life has told me that conflicts don’t usually lead me in the right direction and that I feel more comfortable avoiding them...”. (3.7J). Wishful thinking is defined as the set of cognitive strategies resulting from the desire to live in a non-stressful reality. When this concept is applied to conflict resolution at university, students refer to conflicts that could be avoided if the teaching staff were better trained or with effective conflict resolution institutional bodies. In this way, they express a desire for a university ideal based on inclusion, respect for diversity and academic quality: “... I think that they should be understanding people, that, well, we can’t ask Jesus Christ for anything, but that they should be understanding and help the students...”. (4.2Z). “...It would be ideal that the student representatives, let’s see, that they help you to know how to channel the demands that you have, because sometimes it is as if all the communication goes to the coordinator, but the coordinator is the coordinator of the three courses of study and sometimes he doesn’t remember you, or he doesn’t answer you, because he has more things to do. Apart from that, he is a teacher...”. (4.3E). Within adequate emotion-focused management, the dimensions of social support and emotional expression appear. The students consider that situations of conflict activate emotions, which can become an impediment to dealing with them. However, they consider that the expression of these emotions contributes to conflict management. They also perceive that their expression can sometimes be seen as a weakness that hinders coping: “But maybe that is where it also comes into play that maybe I don’t want to verbalise how I feel because I know I’m going to be attacked. ... I can have the intention of solving the conflict, but if I have that feeling, that vibe that the other person is going to use it against me, then maybe I prefer to keep it to myself, even if I really have to say it...”. (5.2A). One of the strategies that has been identified as fundamental is social support. Students find possible solutions by seeking support from both formal structures (associations, people in charge and/or university mediation organisms, student representatives) and informal ones (classmates, friends, family): “So, I usually go to the source of the problem, and if I see that I am hitting a wall, then I try to get someone else involved. For example, in the case of the teacher, the subject coordinator or whatever. Or with the rest, if it’s a conflict between friends, I try to ask for more opinions, so that I’m not the one in the wrong, but the key is to talk”. (1.2W). “So, you have the level of telling the student subject representative, when there is something that is more organisational, the course student representative. Then we have the one who runs the hall where we study, and then we have to go to the dean to complain. So, increasing the level seems to me to be something that greatly increases efficiency when it comes to resolving conflicts, especially organisational ones, and that there is more agility”. (1.7M). It should be noted that communication between the parties, i.e. being able to talk about what separates people in conflict situations, appears in the students’ discourse as a key issue. “It is also true that I am one of those people who do not keep things quiet. So, if I don’t like something, I say so. I also try to be quite empathetic and put myself in the other person’s shoes, too often, because I think that people act for a reason and, normally, it is for a reason that they believe to be good or fair, but it is true that I am incapable of falling into things. Even if I am uncomfortable, I usually say: “I don’t like the way you are doing things. For the same reason, because communication is the key, and we are not mind readers”. (1.3R). “Yes, because I think that, in the end, many times conflicts are communication problems, and they are solved simply by listening to both parties and seeing what the best way is to get everybody to agree on something”. (1.5Y). Finally, regarding the inadequate management of emotions, the dimensions of social withdrawal and self-criticism emerge, reflecting isolation, self-blame, and self-criticism. Self-criticism is characterised by self-blame and critical reflection on attitude or behaviour: “... it happens to me that there comes a moment when, what I am saying, I am escalating, escalating, escalating and in the end, it is much worse, ... you have ruminated a lot on that conflict and you explode in a way that, if in the first moment, you had externalised it, maybe it could have been managed differently...”. (5.4M). “...I am talking at an academic level and a personal level as well, ..., I recognise that I withdraw into myself and try not to confront myself. Or maybe an uncomfortable situation can happen to me with a classmate, or with a teacher. I don’t do anything, and I get home, and I constantly think about it, and I feel worse because I didn’t act”. (6.5D). Sometimes, perceived difficulties in resolving a conflict or previous negative experiences make students consider social withdrawal as a solution to the conflict. This social withdrawal is activated when students perceive power differences between the parties in conflict and to avoid stress: “But I always consider whether it is worth it or not and whether I can do something or not, because if it is going to generate a lot of discomfort for me to get into an argument between students, then I don’t get involved, because otherwise it is going to affect me much more and I don’t want to”. (4.3E). “In all of this, I decided that as this conflict was not going to be solved, I decided for myself to abandon an internship that was going to leave me with a golden CV. I decided that the best thing to do at that moment is to quit for my mental health”. (6.8C). There are no explicit references that allow us to identify differences when dealing with conflicts and the use of strategies depending on the academic level of studies, gender or situations of diversity. However, students consider that university education and life experience facilitate the incorporation of strategies that allow them to manage conflicts more effectively. In this sense, there is an explicit and crystallised discourse around the importance of mediation training to facilitate conflict management and avoid stressful situations. “I believe that mediation, this subject, should be taught in primary school. It should be compulsory in all fields...”. (1.5Y). “... in the end, this lack, this lack of tools, such as communication, assertiveness, at school, well, maybe they are starting to work... But I think there is a lack of tools, of training to deal with conflict”. (5.3L). Finally, concerning academic satisfaction as a variable that allows us to identify the students’ perception of their university experience, we observe that, despite the presence of conflicts and their consequences, the subjective experience of academic life is positive: “The Complutense, as it is, seems ideal to me. At least in my faculty, I really have professors, their e-mails and who the coordinator is, what is going to be taught in each subject, the number of seminars, the number of syllabuses. All of that is there, and it’s perfect, in English, in Spanish”. (1.8H). “ ...I feel very lucky to have been at this university, to have been given the opportunity, and I often think about it (...). I mean, it is true that sometimes we are not aware of how important it can be to be in an institution. Personally, I am happy. With all the things that have happened, I try to put them in perspective, because I think that the contribution I have received is greater than what it has taken away from me”. (5.3C). This study aimed to analyse the coping strategies used by students at the UCM in conflict situations and their correlation with social and academic variables. The study combined qualitative and quantitative methods, surveying 2,803 students and conducting six focus group sessions. The analysis found a correlation between effective coping strategies, academic satisfaction, and mediation training. Female students tend to employ emotion-focused coping, while those at lower academic levels often resort to avoidance strategies. These insights can shape policies to enhance students’ resources and experiences in higher education. We begin by noting that conflicts are present in all areas of life (Bercovitch et al., 2008) and are inherent to human nature (Huertas, 2013; Rumelili, 2020). In university life, they appear as a central axis in stressful situations based on the findings obtained and coinciding with previous studies (Alcover, 2010; Rojas & Alemany, 2016; Sharififard, 2020). Students view conflicts as intrinsic to interpersonal interactions, recognizing that their resolution can either yield adverse outcomes or foster learning and individual development (Dorado & De la Fuente, 2022). Students believe that communication is an integral aspect, especially in relations with teaching staff (Molt, 2014), with power dynamics playing a fundamental role (Avelino, 2021; Clark, 2008). In line with previous studies (Lasiter et al., 2012), the power imbalances present in the relationships between teachers and students could generate conflict situations in which students opt for inappropriate coping strategies, such as avoidance or social withdrawal. Furthermore, this question coincides with the existing literature: coping strategies depend on the context, cognitive appraisal, and emotions (Londoño et al., 2006). In this sense, the experiences they accumulate throughout their personal and academic lives are what mostly led them to face the conflict in diverse ways (González & Jurado, 2022). Avoidance, social withdrawal, or self-criticism appear then as common coping strategies when cognitive appraisal and emotions generate elevated stress levels. Women use strategies related to emotional expression, desiderative thinking, and social support more frequently, which is in line with previous studies (Salgado & Leria, 2018), which could be explained by gender socialisation. Thus, women typically experience and manage conflicts in a manner consistent with societal expectations and their socialization process (Graves et al., 2021; Pérez-Viejo & Montalvo, 2011). Students at higher levels use strategies linked to problem-solving, cognitive restructuring, and wishful thinking to a greater extent. Conversely, first-year undergraduate students use avoidance strategies more frequently. Higher level students use strategies related to problem solving, cognitive restructuring, and delusional thinking to a greater extent. In contrast, first-year students use avoidance strategies more frequently. Thus, it appears that academic life and maturation fosters strategies that enhance conflict management. Students who have undergone mediation training tend to use appropriate coping strategies, such as problem- and emotion-focused approaches, more frequently. They perceive this training positively as it helps them identify their strengths, areas for improvement, and acquire skills for conflict resolution with lower emotional costs. This aligns with existing literature, emphasizing the importance of conflict management training for enhancing psychosocial well-being (Sahin et al., 2011; Vázquez-Capón & López-Cabarcos, 2016). Conversely, students with mediation training show reduced reliance on problem-avoidance strategies, highlighting the negative emotional impact of inappropriate coping strategies like avoidance on personal well-being (Morán-Astorga et al., 2019). Finally, students experiencing higher academic satisfaction tend to use coping strategies more comprehensively, embracing problem-solving and emotion-focused approaches while minimizing inappropriate methods like wishful thinking and social withdrawal. They credit their satisfaction to the university’s effective conflict management structures, promoting emotional and social well-being among the educational community. Moreover, the acquisition of conflict resolution skills by university members, including staff and faculty, bolsters institutional harmony and coexistence. (Watson et al., 2019). According to Holton (1998), conflict is inevitable in university contexts, due to the complexity derived from their organisation, the diversity of their members, functions, and interests, and/or the hierarchy or scarcity of resources (Alcover, 2010). Based on the cognitive model of Lazarus and Folkman (1984), people assess their resources or strategies in stressful situations, so that greater resources or more appropriate strategies will reduce stress (Cedillo-Torres et al., 2015). In this sense, we agree with Luna (2020) on the need to generate more knowledge about conflict coping styles and strategies, in this case, of university students. The findings suggest the significance of conflicts in university life and their correlation with students’ coping strategies and variables like academic satisfaction, mediation training, gender, and academic level. Therefore, effective coping strategies positively correlate with academic satisfaction and mediation training. Coping strategies are pivotal in students’ university experience, and mediation training appears linked to proficient management of conflict coping strategies and enhanced academic satisfaction. However, there are limitations in the study. In the first place, the impossibility of including other stakeholders (professors, administrative, and support staff) restricted the comprehension of the conflict resolution processes to the student’s perspective. Second, the study is limited to one university. Even though it is a large sample, the results may have varied with students from other universities. Thirdly, it would be interesting to analyse the relationship of coping strategies with other variables such as academic performance, student stress and their perception of their psychosocial well-being. These results should be considered in the formulation of the competencies to be developed from the curricula and academic policies, and to promote responsible citizenship committed to a culture of peace. The design of actions that promote assertive and collaborative coping styles, with strategies to reduce stress and consider conflicts as elements of personal and social development is configured as a transversal axis in university spaces. In short, universities are currently not only repositories and producers of knowledge but also transmitters of this knowledge and of the values involved in promoting the welfare of citizens. Conceiving higher education with a social projection oriented towards the promotion of a culture of peace, transforming people and, therefore, human relations based on respect for diversity, inevitably implies that universities implement educational policies that promote the welfare of their students. By analysing coping strategies in relation to social and academic variables, the research can provide valuable insights into how students at UCM navigate conflicts and challenges. Understanding the relationship between coping strategies and these variables can inform educators and policymakers about potential interventions or support mechanisms to enhance student well-being and academic success. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Dorado Barbé, A., González Casas, D., Ducca Cisneros, L V., & Pérez Viejo, J. M. (2024). Impact of coping strategies on the academic satisfaction of university students and their association with socioeconomic variables. Psicología Educativa, 31(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2024a12 Funding: This study was supported by the Observatory of the Student (UCM). References |

Cite this article as: Barbé, A. D., Casas, D. G., Cisneros, L. V. D., & Viejo, J. M. P. (2025). Impact of Coping Strategies on the Academic Satisfaction of University Students and Their Association with Socioeconomic Variables. PsicologĂa Educativa, 31(1), 1 - 10. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2024a12

Correspondence: davgon14@ucm.es (D. González Casas).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS