Adherence and Engagement in Videoconference Interventions for Treatment-resistant Depression

[La adherencia y el compromiso en intervenciones por videoconferencia para la depresiĂłn resistente al tratamiento]

Adoración Castro1, 2, 3, Pau Riera-Serra1, 3, Guillem Navarra-Ventura1, 3, 4, 5, Inés Forteza-Rey1, 2, 3, Miquel Bennasar-Veny3, 6, 7, Aurora García1, Joan Salvà1, 3, 4, 8, Olga Ibarra1, 3, 8, Rocío Gómez-Juanes1, 3, 4, 8, Mauro García-Toro1, 3, 4, & 8

1University Institute of Health Science Research (IUNICS), University of the Balearic Islands, Palma de Mallorca, Spain; 2Department of Psychology, University of Balearic Islands, Palma de Mallorca, Spain; 3Health Research Institute of the Balearic Islands (IdISBa), Palma de Mallorca, Spain; 4Department of Medicine, University of the Balearic Islands, Palma de Mallorca, Spain; 5CIBER de Enfermedades Respiratorias (CIBERES), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), Madrid, Spain; 6Department of Nursing and Physiotherapy and Research Group on Global Health and Human Development, UIB, Palma de Mallorca, Spain; 7CIBER de EpidemiologĂa PĂşblica (CIBERESP), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), Madrid, Spain; 8Research Network on Chronicity, Primary Care and Health Promotion (RICAPPS), Carlos III Health Institute, Madrid, Spain.

https://doi.org/10.5093/clh2026a4

Received 15 April 2025, Accepted 7 November 2025

Abstract

Background: Adherence and engagement in videoconference therapy are key challenges in the management of treatment-resistant depression (TRD). This study examines adherence and engagement in two videoconference interventions, a lifestyle modification program (LMP) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) in individuals with TRD, exploring predictors of engagement and associations with treatment outcomes. Method: A secondary analysis was conducted using data from a randomized controlled trial (n = 63) comparing LMP and MCBT. Sociodemographic and clinical predictors of engagement were analysed via ordinal logistic regression. Results: Adherence was higher in the LMP group (47.1%) than in the MBCT group (20.7%). Older age predicted greater engagement (p < .020). A trend toward significance was observed between engagement and depression remission (p = .0683). Conclusions: These findings highlight the importance of tailoring those interventions to improve intervention efficacy and improve adherence engagement, but more research is needed to confirm these results.

Resumen

Antecedentes: La adherencia y el compromiso en la terapia por videoconferencia son desafíos clave en el manejo de la depresión resistente al tratamiento (DRT). Este estudio examina la adherencia y el compromiso de dos intervenciones por videoconferencia, un programa de modificación del estilo de vida (LMP) y la terapia cognitiva basada en la atención plena (MCBT) en individuos con DRT, explorando los predictores del compromiso y las asociaciones con los resultados del tratamiento. Método: Se realizó un análisis secundario utilizando datos de un ensayo controlado aleatorizado (n = 63) que comparaba ambas intervenciones. Los predictores sociodemográficos y clínicos del compromiso se analizaron mediante regresiones logísticas ordinales. Resultados: La adherencia fue mayor en el grupo LMP (47.1%) que en el grupo MBCT (20.7%). Una mayor edad predijo un mayor compromiso (p < .020). Se observó una tendencia hacia la significación entre el compromiso y la remisión de la depresión (p = .0683). Conclusiones: Estos resultados ponen de relieve la importancia de adaptar estas intervenciones para mejorar la eficacia de la intervención y mejorar el compromiso con la adherencia, pero se necesita más investigación para confirmar los resultados.

Palabras clave

DepresiĂłn resistente al tratamiento, Videoconferencia, Estilo de vida, Mindfulness, Adherencia, CompromisoKeywords

Treatment-resistant depression, Videoconference, Lifestyle, Mindfulness, Adherence, EngagementCite this article as: Castro, A., Riera-Serra, P., Navarra-Ventura, G., Forteza-Rey, I., Bennasar-Veny, M., García, A., Salvà, J., Ibarra, O., Gómez-Juanes, R., & García-Toro, M. (2026). Adherence and Engagement in Videoconference Interventions for Treatment-resistant Depression. Clinical and Health, 37, Article e260720. https://doi.org/10.5093/clh2026a4

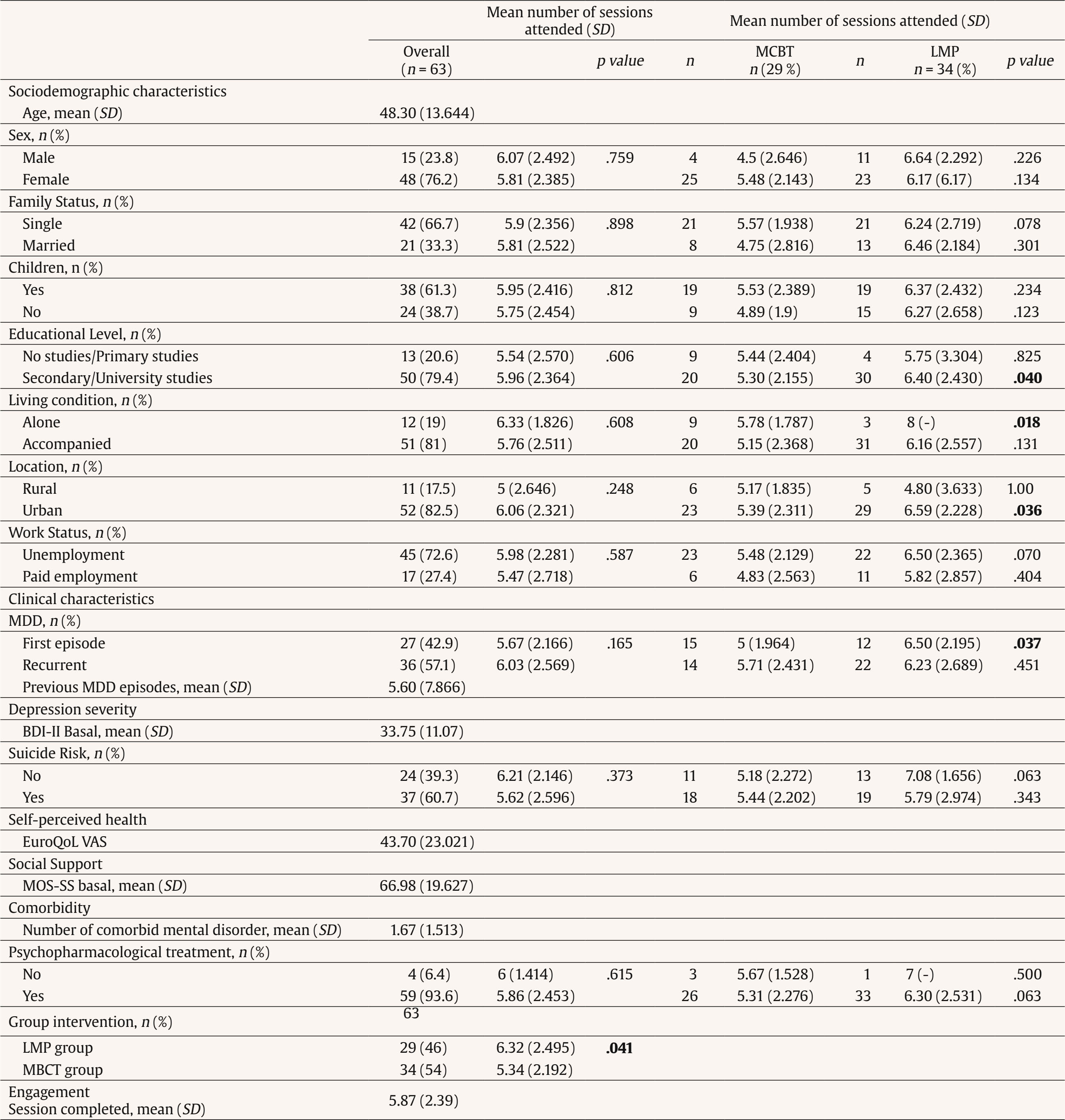

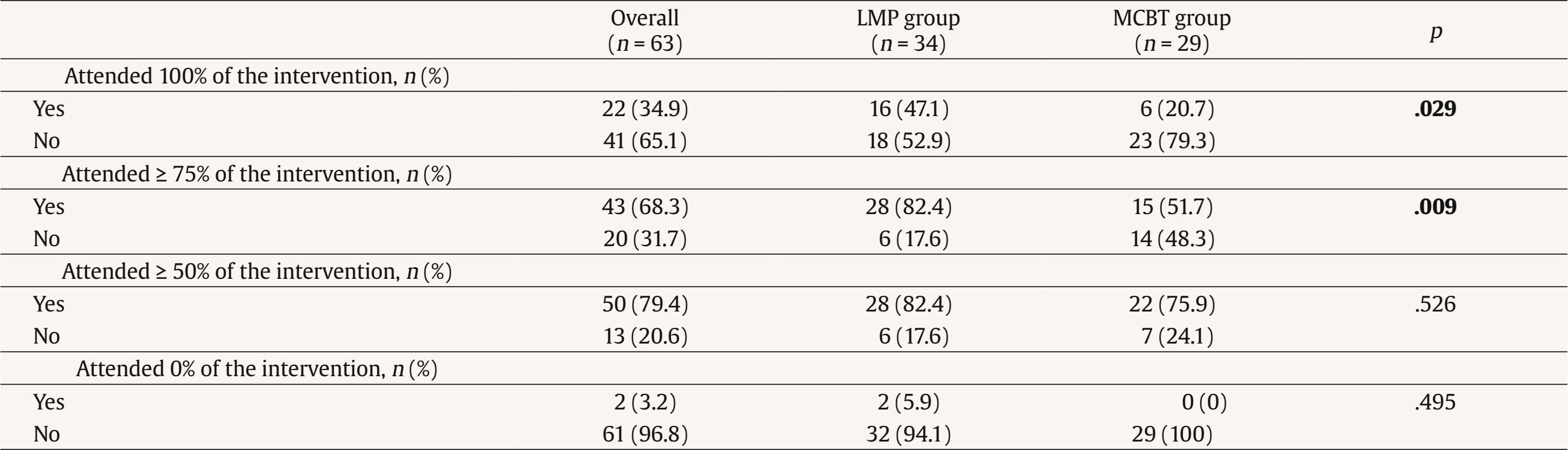

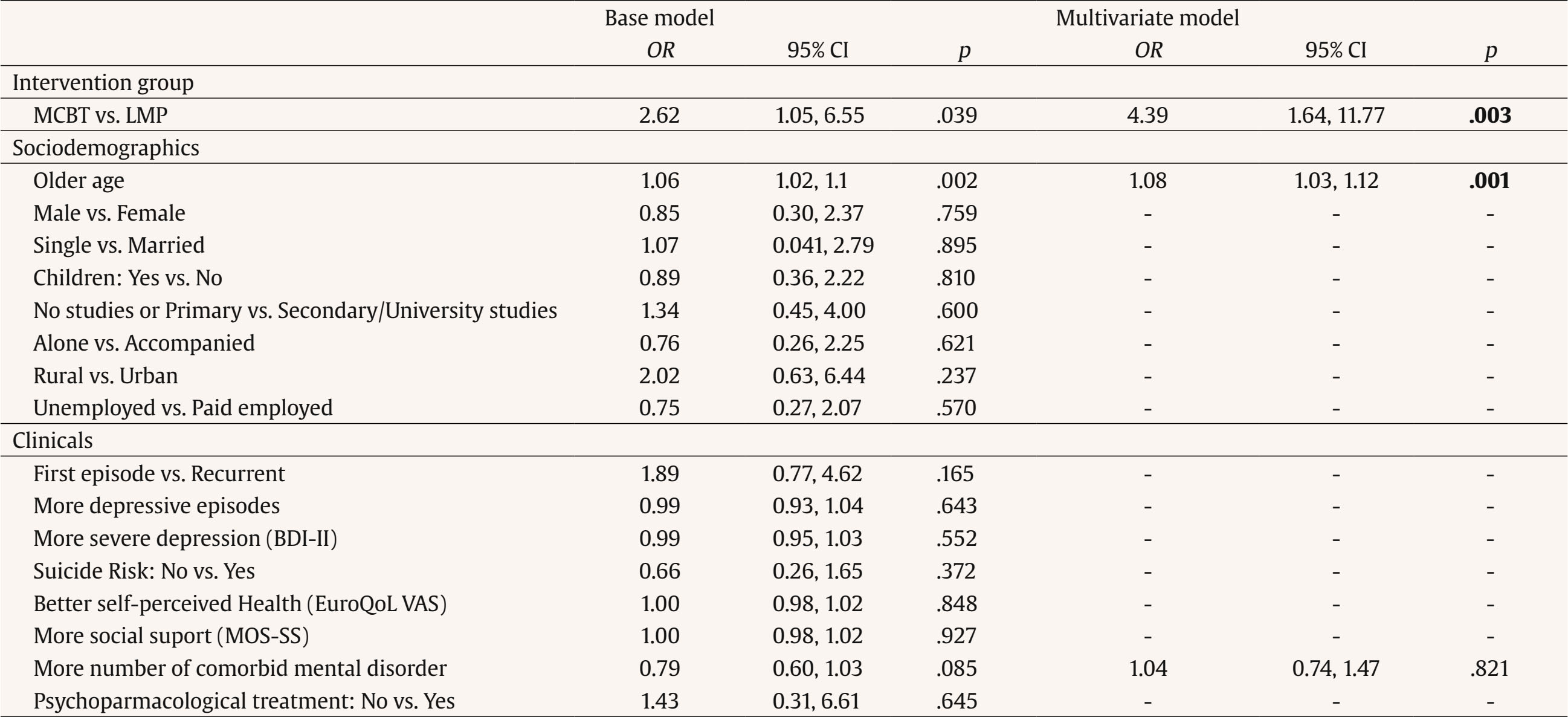

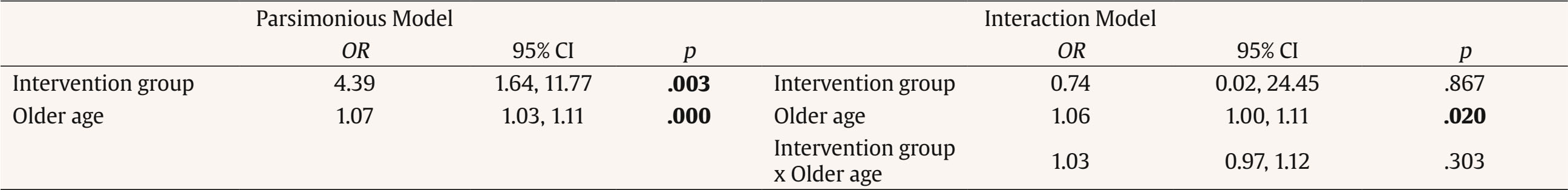

Correspondence: g.navarra@uib.cat. (Guillem Navarra-Ventura).Depression is one of the most prevalent mental disorders globally, affecting approximately 280 million individuals worldwide. Depression rank, together with anxiety, the leading cause of disease burden globally (GBD, 2022) and it is associated with low quality of life, medical comorbidities, and significant economic costs (Gao et al., 2019; Gili et al., 2013; König et al., 2019; Steffen et al., 2020). Patients with major depressive disorders who do not respond to two or more antidepressants are generally considered as patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) (Brown et al., 2019; Conway et al., 2017b, 2017a; Gaynes et al., 2020). For this specific patient population, alternative treatments should be considered. Previous research has shown that lifestyle interventions are convenient for patients with depression (Gómez-Gómez et al., 2020; Wong et al., 2021). However, evidence in patients with TRD is limited (Garcia et al., 2023). Another treatment that has been widely studied is Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT). Research has shown its effectiveness in treating depression and preventing relapse (Hervás et al., 2016; MacKenzie et al., 2018; McCartney et al., 2021; White, 2015), even in TRD patients (Cladder-Micus et al., 2018; Eisendrath et al., 2016; Foroughi et al., 2020). Recent studies have shown a significant increase in the use of technology for therapeutic interventions in the past few years (Muñoz et al., 2021; Zale et al., 2021). It is well known that face-to-face treatments can present logistic and personal barriers (Bower & Gilbody, 2005; Brenes et al., 2011; Kazdin & Blase, 2011; Kazdin & Rabbitt, 2013; Webb et al., 2017), and teletherapy has the potential to overcome these barriers. Regarding videoconferencing, previous research has been shown that it is equal to in person psychotherapy in terms of efficacy for different mental health conditions, including depressive disorders (Berryhill et al., 2019; Giovanetti et al., 2022; Shaker et al., 2023). The treatment outcomes, such as adherence or engagement, provide relevant information about those interventions. Hungerbuehler et al., 2016 assessed, among other outcomes, treatment adherence for two different treatment conditions (monthly in-person consultations with their psychiatrists versus monthly home-based consultations with their psychiatrists through videoconference) for patients with mild depression. Results showed that there were no significant differences between groups except after 6 months, when the dropout rate was significantly higher in the in-person group. However, to our knowledge, no studies have been examining predictors of adherence or engagement to interventions delivered via videoconferencing to patients with depression or TRD, except for Wu et al., 2022, who identify specific predictors of non-initiation of care and dropout in a blended care CBT intervention, involving videoconferencing sessions and digital activities, for depression and anxiety. To address this research gap, the present study aims to explore adherence and engagement in two interventions delivered via videoconference (a lifestyle modification program (LMP) and a mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MCBT)) for patients with TRD. Specifically, the study aims: 1) to examine differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics in the treatment engagement in the overall sample and between intervention groups, 2) to determine treatment adherence rates, 3) to identify engagement predictors, and 4) to analyze the association between engagement and treatment response. Study Design The current study is a secondary analysis of the randomized controlled trial (RCT), which aimed at comparing the effectiveness of a LMP with a MCBT group and with placebo treatment, in patients with TRD. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04428099) and received ethical approval by the Research Ethics Committee of the Balearic Islands (IB3925/19PI; 29-5-2019). The study design was developed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. All participants gave written informed consent to participate following detailed explanations of the study protocol. The research protocol and main results have been published elsewhere (Garcia et al., 2023; Navarro et al., 2020). Participants In the original study, 94 patients with TRD were recruited, between January 2020 and February 2021 in the Balearic Islands (Spain). Inclusion criteria were: > 18 years of age, a diagnosis of an episode of TRD, determined by major depressive disorder according DSM-5, the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) criteria, and at least two failed or refused psychopharmacological treatment, prior care by a mental health professional for at least 1 month, sufficient physical capacity and cognitive ability to understand and participate in the study, and access to the technologies and skills needed to participate in online videoconferences at home. We excluded patients who were inability to speak Spanish, with a diagnosis of another disease that affects the central nervous system or any psychiatric diagnosis or severe psychiatric illness according to the MINI criteria, having a serious or uncontrolled medical, infectious, or degenerative illness that may affect mood, present delirium or hallucinations, be pregnant or breastfeeding, with high risk of suicide, or present any medical, psychological, or social condition that could significantly interfere with participation in the study. For the present analysis, 63 participants were included, those who were allocated to one of the intervention groups. Those allocated to the Placebo-control group were excluded from the analysis because they had no access to treatment. Intervention Groups Description The LMP group involves written suggestions for lifestyle changes and 8-week lifestyle promotion program. This intervention includes topics about depression and lifestyle recommendations. The MCBT group involves also written suggestions for lifestyle changes and an 8-week MCBT program. This intervention includes topics about depression and mindfulness strategies. Interventions were remotely implemented via an online platform. Both interventions were group-based, including around 15 participants in each one, so two editions of both interventions were carried out. Therapists, who were trained mental health experts, conducted both intervention groups and assessed patient engagement. In addition, they provided individual support online through chat and telephone calls. Detailed descriptions of the intervention groups can be found in prior publications (Garcia et al., 2023; Navarro et al., 2020). Adherence and Engagement Definition Adherence to treatment was defined as the percentage of participants who attended a specific part of the intervention and Engagement as the number of sessions attended by participants. Therapists recorded this information, considering a session attended if the participant completed the scheduled session. Predictors of Engagement Sociodemographic variables included age, sex (male vs. female), family status (single vs. married), having children (yes vs. no), educational level (no studies/primary studies vs. secondary/university studies), living condition (alone vs. accompanied), living location (rural vs. urban), and work status (unemployment vs. paid employment). Clinical characteristics included major depressive disorder (first episode vs. recurrent), the presence of suicide risk (no vs. yes) and the number of comorbid mental disorders evaluated by the Spanish version of the M.I.N.I. 5.0 (Ferrando et al., 1998; Sheehan et al., 1998), the severity of depressive symptoms measured by the Spanish version of Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) (Beck et al., 1996; Sanz et al., 2005), the self-perceived health, measured by the Spanish version of The Visual Analog Scale of the EuroQol (VAS) (Badia & DeCharro, 1999), social support, assessed by the Spanish version of the Medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SS) (Revilla Ahumada et al., 2005; Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991), the number of previous MDD episodes, and the psychopharmacological treatment (no vs. yes). Those data were collected at baseline through a telephone interview. Data Analysis The intervention groups were selected based on the assigned treatment delivered through videoconference (LMP vs. MCBT). Descriptive analyses were performed in terms of mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and an analysis of frequency and percentages for ordinal and nominal variables. Differences in the number of sessions attended between intervention groups were compared using the non-parametric test Mann Whitney-U, due to the variable “number of sessions attended” did not meet the assumption of normality. Ordinal multinomial logistic regression models were carried out to identify predictors of sessions attended. Base models including intervention group, sociodemographic and clinical variables were used to assess the influence of the predictors. Afterwards, potential predictors (p < .10) were included in a multivariate model. Finally, the most parsimonious model and interaction model were built to identify final predictors. To examine the relationship between engagement and depressive symptomatology, the Mantel-Haenszel test for linear association was performed. Analysis was conducted for remission (Post BDI-II score < 13), total response (a reduction of 50% or more in BDI-II post follow-up score compared to basal BDI-II score), and partial response (reduction of 25% or more in BDI-II post follow-up compared to basal BDI-II score). Statistical analyses were performed using the STATA 17.0 program and a significant level of p < .05 was considered statistically significant. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants with Treatment-resistant Depression The sample was predominantly female (76.2%), with a mean age of 48.3 (SD = 13.64). Most participants were single (66.7%), had children (61.3%), had completed secondary/university studies (79.40%), and lived with others (81%) in urban areas (82.5%). Regarding clinical characteristics, the mean scores on the BDI-II at baseline was 33.75 (SD = 11.07), indicating severe depressive symptomatology. More than half of the participants (60.7%) were at minimal risk of suicide and 93.6% were using psychopharmacological treatment. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample at baseline. Table 1 Baseline Characteristics and Sociodemographic and Clinical Differences in Treatment Engagement in the Overall Sample and between Intervention Groups   Note. Bold numbers show where significant differences between groups are. SD = standard deviation; MCBT = Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; LMP = lifestyle modification program; MDD = major depressive disorder; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; EuroQoL VAS = visual analogue scale from the EuroQoL; MOS-SS = medical outcomes study social support survey. Adherence to Videoconference Interventions Nearly 35% of participants attended the whole intervention, while 68.3% attended 75% or more of the intervention, and 79.4% attended more than half of the treatment. Only 3.2% did not start the treatment. Regarding differences between LMP and MCBT groups, statistically significant differences were observed in the percentage of participants who attended the whole intervention (LMP group: 47.1% vs. MCBT group: 20.7%, p < .029) and the percentage of participants who attended 75% or more of the intervention (LMP group: 82.4% vs. MCBT group: 51.7%, p < .009). Adherence differences between the intervention groups are in Table 2. Table 2 Adherence to Intervention Groups   Note. Bold numbers show where significant differences between groups are. MCBT = Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; LMP = lifestyle modification program. Treatment Engagement by Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics in Videoconference Interventions Overall, the mean number of sessions attended was 5.87 (SD = 2.39, range 0-8). There were no significant differences in the mean number of sessions attended between any variable, except for intervention groups (LMP group mean = 6.32 vs. MCBT group mean = 5.34 p < .41). When comparing between intervention groups, statistically significant differences were found in the mean number of sessions attended in the following variables: Educational Level - Secondary/University (MCBT group mean: 5.30 vs. LMP group mean: 6.40, p = .040); Living condition - Alone (MCBT group mean: 5.789 vs. LMP group mean: 8, p = .018); Living location - Urban (MCBT group mean: 5.39 vs. LMP group mean: 6.59, p = .036) and MDD - First episode (MCBT group mean: 5 vs. LMP group mean: 6.50, p = .037). Differences in treatment engagement between intervention groups are in Table 1. Table 3 Ordinal Multinomial Logistic Regression Models on the Number of Sessions Attended   Note. Bold numbers show significance at p < 0.05 level; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence Interval; MCBT = Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; LMP = lifestyle modification program; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; EuroQoL VAS = Visual analogue scale from the EuroQoL; MOS-SS = medical outcomes study social support survey. Predictors of Engagement in Videoconference Interventions: Ordinal Logistic Regression Results Table 3 shows the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval for each predictor variable of the number of sessions attended. Intervention group (p = .039), age (p = .002) and comorbidity (p = .085) were identified as potential predictors in base models and included in the multivariate model, resulting intervention group (p = .003) and age (p = .001) remained significant predictors of engagement. The most parsimonious model to predict engagement, based on our sample and predictors, are shown in Table 4. The intervention group emerged as a significant predictor variable, specifically, being in LMP group was associated with 339% greater odds (95% CI [1.64, 11.77]) of attending one more session compared to being in MCBT group. Age was also a significant predictor: for every one-year increase, there was a 7% higher probability (95% CI [1.03, 1.11]) of attending the sessions. When an interaction between intervention group and age was included in the model only age remained significant: for every one-year increase, there was a 6% higher probability (95% CI 1.00, 1.11]) of attending the sessions. Table 4 Most Parsimonious Model and Interaction Model on the Number of Sessions Attended   Note. Bold numbers show significance at p < .05 level; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. Associations between Engagement and Treatment Outcomes The Mantel-Haenszel test showed a trend towards significance in the association between engagement and remission (χ2 = 3.323, p = .0683). No significant linear association were found between engagement and total treatment response (χ2 = 0.258, p = .611) nor engagement and partial treatment response (χ2 = 0.042, p = .836). The main objective of this study was to explore adherence and engagement of two interventions delivered via videoconference for patients with TRD. Our results indicate a low adherence rate in the overall sample at 35%. This contrasts with findings from a previous RCT comparing face-to-face to videoconference-based CBT for mood and anxiety disorders, where 11 out of 14 patients completed the full intervention. However, it is important to note that this RCT involved a small sample size of patients with a broad spectrum of disorders, not solely depression (Stubbings et al., 2013). It is noteworthy that our adherence rates increase as the percentage of completed treatment decreases: almost 70% of participants attended 75% or more of the sessions and 80% completed half or more of the treatment. This suggests that although the percentage of individuals who finished the entire treatment was small, a substantial portion of the sample was exposed to a considerable portion of the treatment content. When we compared adherence rates between the intervention groups, our findings revealed that the LMP group had a greater number of participants attending 100% and 75% of the treatment, as well as a higher average number of sessions completed, compared to the MCBT group. These results suggest that adherence and engagement to the LMP group were higher to those of the MCBT group. Previous studies have demonstrated similar adherence rates for both intervention modalities. For lifestyle interventions, a systematic review and meta-analysis showed that 53% of participants completed the entire intervention (Castro et al., 2021). A recent study that assessed the effectiveness and adherence to group intervention based on mindfulness in patients with anxiety and depression in a community mental health center found that approximately 57% of participants completed seven or more sessions out of nine (Fort-Rocamora et al., 2024). Although previous research has found an association between self-reported unhealthy lifestyle behaviors and symptoms of depression during the COVID-19 lockdown (Simjanoski et al., 2023), one possible explanation for the observed results could be that, since the intervention took place during the lockdown, and subsequently during the easing of restrictions, participants may have felt the need to engage in outdoor activities. LMP guidelines emphasize outdoor activities, such as physical exercise, fostering relationships, exposure to sunlight, and contact with nature, among other factors, which could have encouraged engagement and adherence to treatment. Upon examining the differences in the mean number of sessions attended between characteristics, no variable was found to be associated with engagement except for intervention groups, as previously mentioned. However, when comparing the interventions, we observed differences in specific sociodemographic and clinical variables. Participants in the LMP group with a higher education level, living alone, living in urban areas, and/or experiencing a first episode of MDD attended a greater number of sessions compared to those in the MCBT group. Regarding predictors of engagement, our results indicate that age was the sole predictor of engagement, measured as the number of sessions attended: older individuals tended to attend more sessions than younger individuals in an intervention delivered via videoconferencing. Given the small sample size, analyses were conducted on the entire sample. Nonetheless, the intervention group variable was included as a potential predictor; after the interaction model was assessed, only age maintained its significance as a predictor. Only one study was identified that examined predictors of non-initiation of care and dropout in a blended care CBT intervention (Wu et al., 2022). This analysis included more than 3,500 individuals with clinical levels of anxiety and depression and identified a large number of predictors of non-initiation and dropout, but age played no role in it. However, age, and specifically being older, has been identified in previous studies as a predictor of adherence and engagement in online treatments for depression and other mental health disorders (Castro et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2020; Kazlauskas et al., 2020). Nevertheless, it is important to note that different definitions of adherence and engagement are used across the studies. Therefore, these comparisons must be treated with caution. Finally, our results show a trend towards significance in the positive association between engagement and depression remission. This aligns with previous studies that have found a significant relation between engagement and/or adherence and positive outcomes, particularly in digital interventions (Donkin et al., 2013; Mohr et al., 2013). The present research has several limitations. The major limitation is the small sample size leading to a lack of statistical power and preventing the identification of engagement predictors for each intervention group. Another limitation is that we have analyzed two common metrics on adherence and engagement, based on the number of sessions attended, although it is recommended that additional measures of engagement be examined in the same analysis to a major comprehension of this topic (Donkin et al., 2011). Despite these limitations, our study presents strengths. Although this study is on a small scale, it provides valuable information about adherence and engagement to two interventions delivered via videoconference for patients with TRD, analyses many sociodemographic and clinical predictors to find the most effective predictive model for the data available, and explores the relationship between adherence and treatment response, with the aim of understanding how they relate to each other. The key findings of this study are: first, our treatment adherence rate is relatively low; second, only intervention group was associated with engagement in the overall sample. When we compared between intervention groups, specific variables are associated with engagement: participants in the LMP group with a higher education level, living alone, living in urban areas, and/or experiencing a first episode of MDD attended a greater number of sessions compared to those in the MCBT group; third, age is a predictor of engagement, measured as the number of sessions attended – older individuals tended to attend more sessions than younger individuals in a videoconference-delivered intervention; finally, it has been shown that there is a trend towards a positive association between engagement and depression remission. These findings highlight the importance of tailoring those interventions to improve intervention efficacy and improve adherence engagement. For instance, including digital components such as an app to log mindfulness practice could serve as a motivational tool and help reduce dropout rates (Horrillo-Álvarez et al., 2019). Further research into larger samples is needed to confirm these results.

Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Acknowledgements We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to the patients who took part in this study, as well as to the dedicated healthcare professionals who assisted us in this endeavour. Cite this article as: Castro, A., Riera-Serra, P., Navarra-Ventura, G., Forteza-Rey, I., Bennasar-Veny, M., García, A., Salvà, J., Ibarra, O., Gómez-Juanes, R., & García-Toro, M. (2026). Adherence and engagement in videoconference interventions for treatment-resistant depression. Clinical and Health, 37, Article e260720. https://doi.org/10.5093/clh2026a4 Funding This study was funded by Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities grant number MCIN/ AEI/10.13039/501100011033/RTI2018–093590-B-I00, following a rigorous peer-reviewed (co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund/European Social Fund; “A way to make Europe”). Rocío Gómez-Juanes received honoraria for speaking and consulting from Janssen outside the submitted work. References |

Cite this article as: Castro, A., Riera-Serra, P., Navarra-Ventura, G., Forteza-Rey, I., Bennasar-Veny, M., García, A., Salvà, J., Ibarra, O., Gómez-Juanes, R., & García-Toro, M. (2026). Adherence and Engagement in Videoconference Interventions for Treatment-resistant Depression. Clinical and Health, 37, Article e260720. https://doi.org/10.5093/clh2026a4

Correspondence: g.navarra@uib.cat. (Guillem Navarra-Ventura).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS