Mediation: Understanding a Constructive Conflict Management Tool in the Workplace

Special issue on "Theory Development and Research Review" in Homage to Professor Jos├ę Mar├şa Peiro

[La mediaci├│n: una herramienta de gesti├│n constructiva del conflicto en el lugar de trabajo]

Lourdes Munduate1, Francisco J. Medina1, and Martin C. Euwema2

1University of Seville, Spain; 2K.U. Leuven, Belgium

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2022a20

Received 16 July 2021, Accepted 24 October 2022

Abstract

Mediation becomes relevant nowadays as a way to manage conflicts in the workplace in a nonjudicial way, preventing costly, extensive, and unsatisfying legal procedures. This study tries to systematize the more recent research about mediation, showing the main challenges, questions, and findings. Research suggests the importance of integrating the organizational and societal context in the study of mediation, the use of efficiency, equity, and voice objectives for evaluating mediation effectiveness, and taking into account a contingency approach in mediator strategies. There is an important gap between the large development of professional practice in mediation and the few systematic studies on this topic. This paper offers a model that considers current research and practice for mediation effectiveness. This model could be used to focus the orientation of scholars, practitioners, and governments in search of new developments in the design of mediation. Future research could explore specific combinations of these dimensions to analyze sectors, organizations, or cases of mediation.

Resumen

La mediación está adquiriendo relevancia hoy en día como una forma extrajudicial de gestionar los conflictos, evitando procedimientos legales costosos, largos e insatisfactorios. Este estudio trata de sistematizar la investigación más reciente sobre la mediación, mostrando los principales retos, cuestiones y conclusiones. La investigación sugiere la importancia de integrar el contexto organizativo y social en el estudio de la mediación, el uso de objetivos de eficiencia, equidad y voz para evaluar la eficacia de la mediación y tener en cuenta un enfoque contingente en las estrategias de las personas mediadoras. Existe una importante brecha entre el gran desarrollo de la práctica profesional de la mediación y la escasez de estudios sistemáticos sobre este tema. Este artículo ofrece un modelo que tiene en cuenta tanto la investigación como el ejercicio práctico para entender cómo se producen las mediaciones eficaces. Este modelo podría utilizarse para orientar a la academia, el ejercicio profesional y a los gobiernos en la búsqueda de nuevos desarrollos en el diseño de la mediación. Las investigaciones futuras podrían explorar combinaciones específicas de estas dimensiones para analizar sectores, organizaciones o casos de mediación.

Palabras clave

Mediaci├│n, Mediaci├│n en el trabajo, Conflicto organizacional, Soluci├│n alternativa de conflictos (SAC)Keywords

Mediation, Workplace mediation, Organizational conflict, Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)Cite this article as: Munduate, L., Medina, F. J., & Euwema, M. C. (2022). Mediation: Understanding a Constructive Conflict Management Tool in the Workplace. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 38(3), 165 - 173. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2022a20

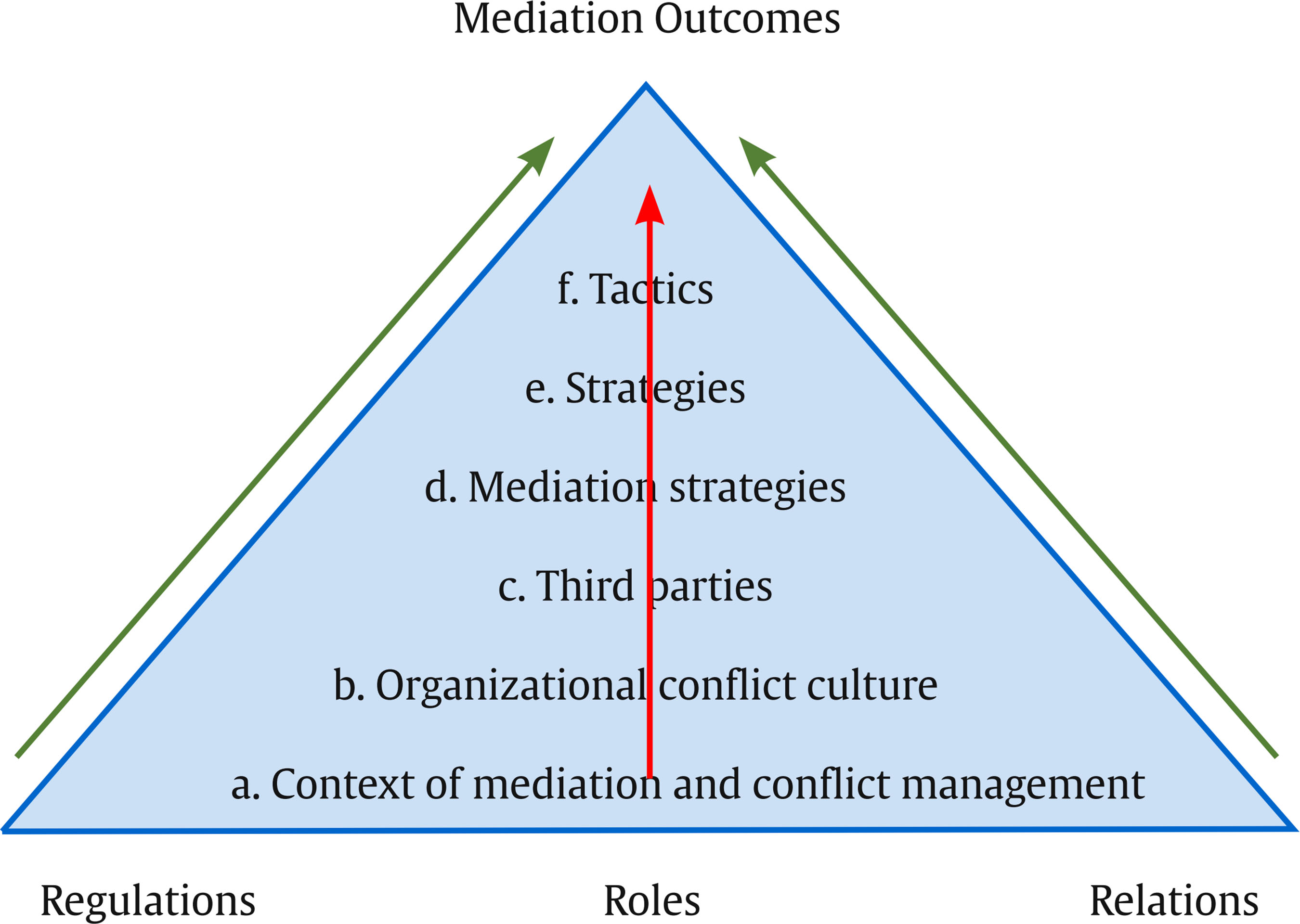

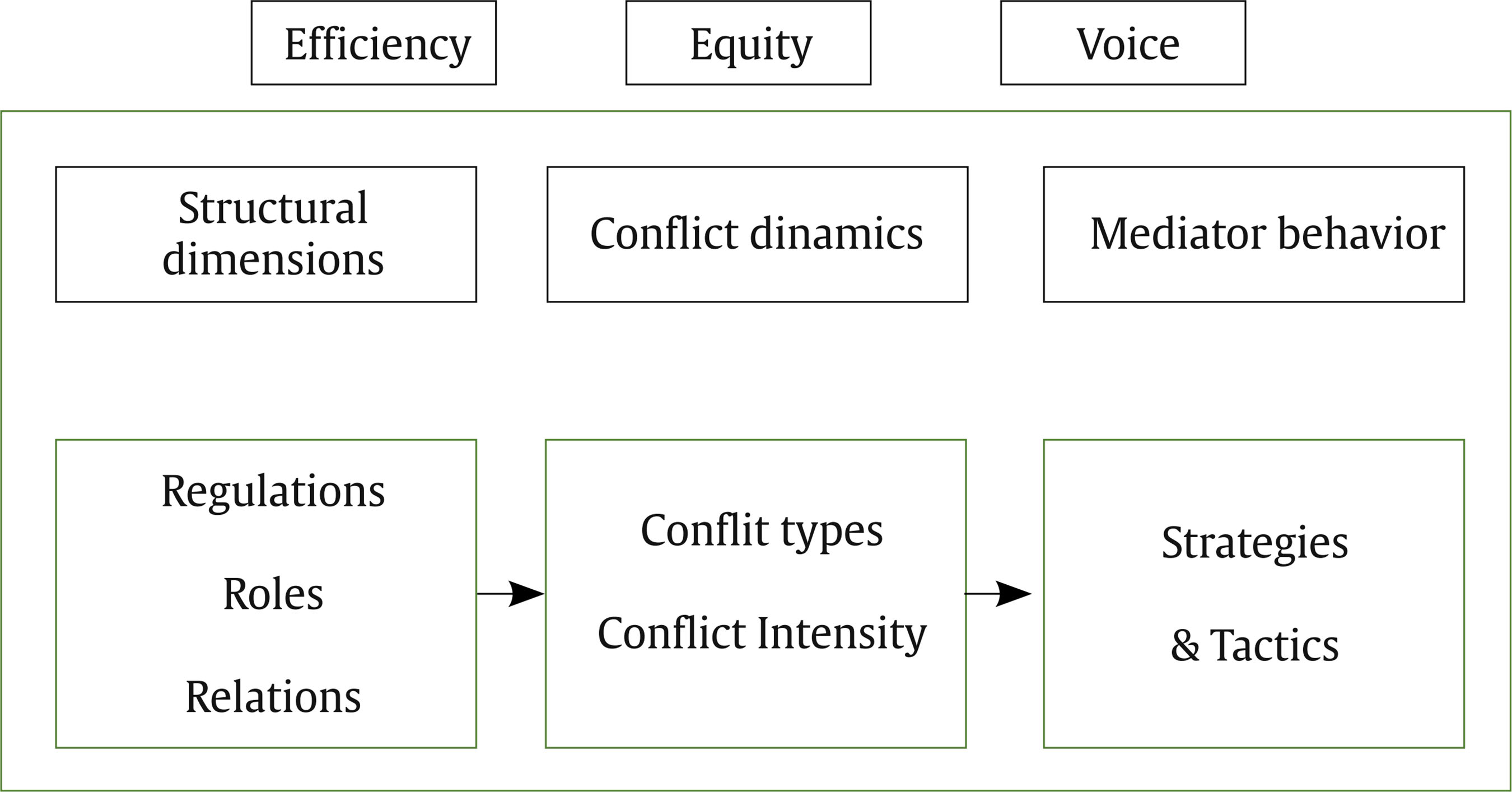

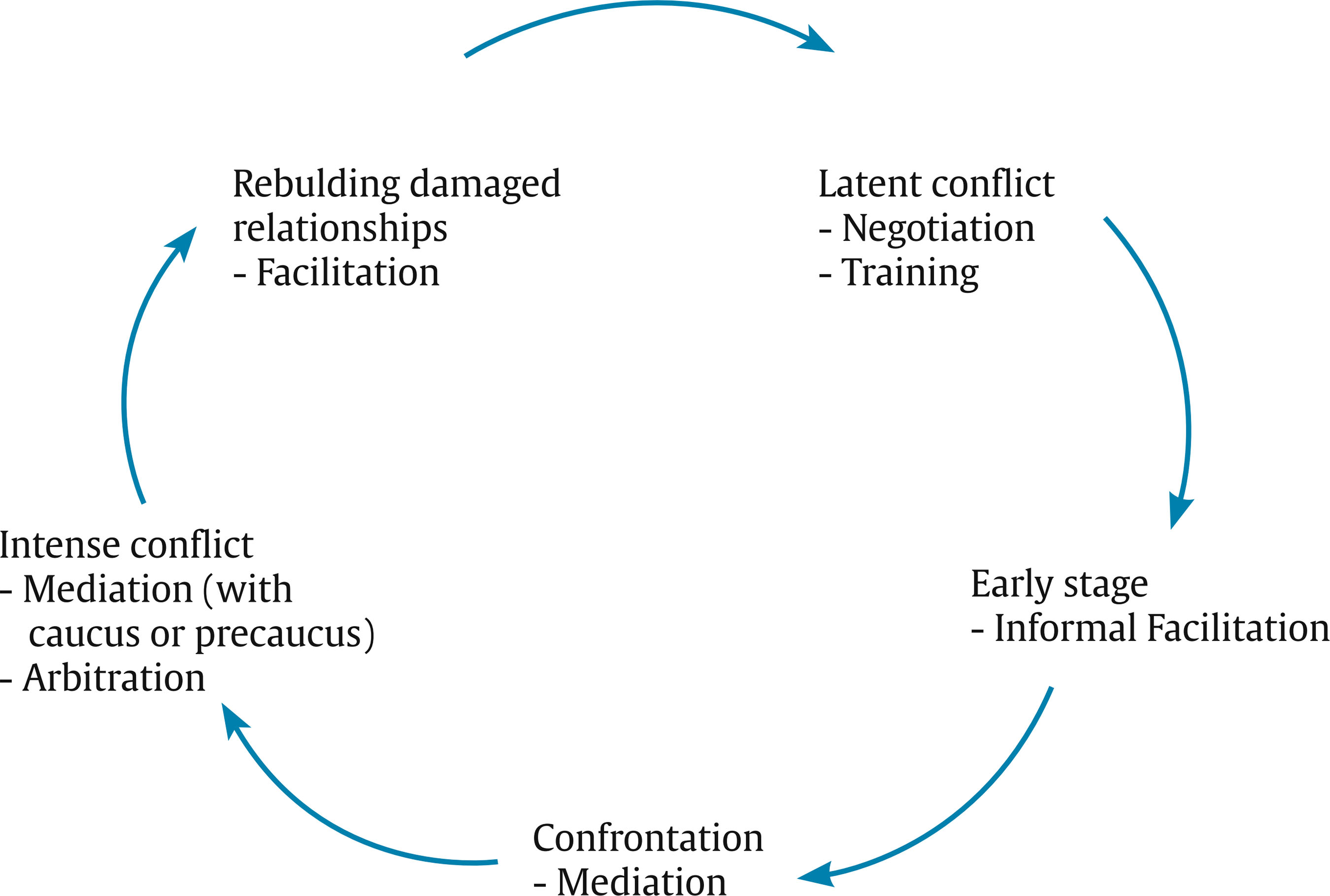

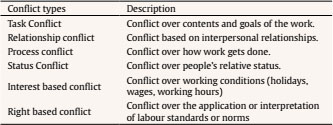

fjmedina@us.es Correspondence: fjmedina@us.es (F. J. Medina).Conflict management research recognizes that conflicts in organizations are inevitable and can take a constructive or destructive course (Tjosvold et al., 2014). Conflict management therefore is a core part of organizational practices, and particularly leaders and managers spend a large amount of time on the prevention of and intervention in conflicts of all kinds. The way conflicts are managed reflects key elements of the organizational culture or socially shared norms and are referred to as the organizational conflict culture (Gelfand et al., 2012). Gelfand et al. (2012) found that conflict cultures can take the form of: a) “collaborative” conflict cultures, wherein there is a collective constructive dialogue, negotiation, and joint problem solving; b) “dominating” conflict cultures, wherein organizational members collectively seek a competition and victory and try to outwit others; or c) “avoidant” conflict cultures, wherein organizational members collectively suppress and withdraw from conflict. Their study shows that collaborative conflict cultures contribute to healthier, more productive, and more innovative organizations. In such cultures, conflicts are recognized as inevitable and potentially constructive and integrative problem solving is encouraged. The creative potential of these conflicts is optimally used, while the destructive effects of conflict are prevented (Katz & Flynn, 2013). Such cultures also offer fertile soil for third-party support in conflict, including mediation. Mediation is used in different types of conflicts: within the organization, in both lateral and hierarchical relations, but also in conflicts with suppliers, clients, governments, and other stakeholders. Mediators can act in highly escalated collective confrontations between management and workers, but also in daily conflicts between two employees (Bollen et al., 2016) Since conflicts often have destructive effects on both the organization and the people involved (De Dreu, 2008; Giebels & Janssen, 2005), the main challenge is to manage these conflicts in a constructive way (De Dreu & Van de Vliert, 1997), as the consequences of an escalated conflict could be extremely negative for the organization and for the people involved. A recent analysis in UK estimates the damage of conflict to the economy at 28.5 billion pounds, which is equivalent to 1,000 pounds per year for each employee (Saundry & Urwin, 2021). Similarly, considering personal consequences, conflict has a deep negative impact on employees. More than half of the workers (56%) felt stress, anxiety, and/or depression, 40% reported less motivation, and about 5% of the employees who experienced conflict left the organization (Saundry & Urwin, 2021). To prevent costly, lengthy, and unsatisfying legal procedures, mediation has been stimulated throughout the world. Mediation is a form of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) used to solve different types of labor conflict in a nonjudicial way (Bollen, et al., 2016). Europe has traditionally shown a marked reluctance to use extrajudicial strategies like mediation as a means of settling disputes in the workplace, partly due to the stronger role of trade union representatives and legalization of labor relations (Rodriguez-Piñero et al., 1993). Currently however, labor mediation is more often promoted as a constructive way to limit the high costs of work disputes both at a collective and interpersonal level (Elgoibar et al., 2019). An example of the trend to promote mediation in and among European countries refers to the European mediation directives approved by the European Parliament in 2008 and 2013 (Directive 2008/52/CE and Directive 2013/11/EU). The stated objective is "to facilitate access to dispute resolution and to promote amicable settlement of disputes by encouraging the use of mediation and ensuring a balanced relationship between mediation and judicial proceedings" (Art. 1). In line with this, centers offering workplace mediation services, both public and private, have been opened in different European countries (Bollen & Euwema, 2013), and in several European regulations mediation has been incorporated to increase efficiency in employment relations and reduce ‘the burden’ on the employment tribunal system (Deakin, 2016). In the United States, important workplace mediation programs sponsored in both the public (Bush, 2001) and private sector (Kressel, 2014) represent major milestones in the development of workplace mediation. In short, we are at a time when mediation is flourishing worldwide. The Use of Mediation in Labor Settings It is important to distinguish between mediation that takes place within organizations (workplace mediation) with mediation usually taking place in external mediation structures, like SIMA in Spain or ACAS in UK, or in special contexts as happens in prejudicial mediation (labor mediation). All of those are interventions by a third party that attempt to handle disputes employees have with their employers or with their own colleagues, both in collective and individual conflicts. Both types of mediation (workplace & labor mediation) deal with existing disputes in organizations between stakeholders who usually have a long-standing relationship which will continue when mediation ends. However, there is a relevant difference between the two: while the former usually occurs in an unregulated context, the latter takes place in a regulated context under a legal umbrella. The term labor mediation is used to describe those formal external processes of mediation that usually exists prior to the court or actions such as a strike (Euwema et al., 2019). Mediation is a process in which a third party facilitates a constructive communication among disputants, including decision-making, problem-solving, and negotiation, to reach a mutually acceptable agreement (Bennett, 2013, 2014; Goldman et al., 2008; Moore, 2014). In this process, the mediator acts as a guardian of the process, while refraining from an evaluation of the case or directing parties to a particular settlement (Kressel, 2014; Wall et al., 2001). The mediator’s role is to help disputants to better understand each other’s concerns and interests. Criteria for Mediation Effectiveness: Promoting Efficiency, Equity, and Voice In order to assess the suitability and appropriate forms of mediation, it is needed to consider a more global approach, which is provided by the employment relations perspective (Munduate et al., 2016). As Budd and Covin (2008) point out, there is a lack of consensus among researchers on what exactly constitutes the effectiveness of the grievance procedure. Therefore, it is difficult to compare mediation with other forms of workplace conflict resolution. First, there is a wide array of terminologies used (facilitation, conciliation, mediation), which contribute to some confusion. For this work, and in accordance with a European directive in 2008, we will consider the term mediation as an umbrella to identify the intervention of third parties in a dispute, accepting the rest of the terms as different approaches that mediators can use in their work. Second, many criteria are used to analyze the effectiveness of mediation, in some cases contradicting each other. These authors identify and develop three critical standards that can be compared across all types of dispute resolution procedures: efficiency, equity, and voice. The perceived “efficiency” of mediation over conventional complaints and grievance procedures has been analyzed in terms of cost, speed, success/agreements, and satisfaction (Saundry et al., 2018). The speed literature typically analyzes how long it takes to resolve grievances and at what step of the process grievances are resolved compared to mediation (Budd & Covin, 2008). The satisfaction literature typically surveys parties to measure mediation success, in terms of agreements reached, satisfaction with these agreements, or perceived procedural justice (for example, Bollen & Euwema, 2013). The prevention of costly, lengthy, and unsatisfying legal procedures has been used as a criteria to promote efficiency advantages of workplace mediation. However, efficiency criteria have not been without controversy over the disadvantages of power imbalance between disputants. As Dolder (2004) points out, workplace mediation assumes that the parties are equal and capable of participating in the production of individual solutions. However, often a disparity of power is observed between the parties, which not simply resides in the hierarchical relationship between them but in the degree to which they are able to articulate their views, their level of formal education, or extraversion (Bollen & Euwema, 2013; Medina et al., 2008). This power imbalance between disputants may shape the conduct and outcome of the process (Bollen et al., 2012; Bollen & Euwema, 2013; Sherman, 2003). As Jordaan and De Wulf (2016) state, while mediators can maintain a degree of equality within the process, they cannot change the fundamental power relationships that exist between parties, nor can they protect the weaker party outside the mediation session itself (Sherman, 2003), and consequently, the ‘weaker’ party may be too intimidated to contribute fully to the process (Wiseman & Poitras, 2002). The pertinent question in workplace mediation therefore is: are disputants sufficiently capable of negotiating with each other as equals, or will this merely reinforce the existing power imbalance? (Bollen & Euwema, 2013, 2015; Dolder, 2004; Sanders, 2009). This topic of power imbalance is especially accentuated by the criticism of the appropriateness of workplace mediation in the case of bullying and mistreatment at work (e. g., Branch et al., 2009; Keashly & Nowell, 2011). This criticism argues that mediation could be seen as a shift towards silencing social criticism by hiding the process of conflict resolution from the public scrutiny (Ridley-Duff & Bennett, 2011). Furthermore, to the extent that mediation focuses on the future and reconciliation, it has no mechanism to address or ‘punish’ past behavior, where in the case of clearly defined victims and offenders such a mechanism might be desirable (Keashly & Nowell, 2011). To assess suitability and appropriate forms of mediation, qualities and effectiveness must be considered in the broader employment relations system (Munduate et al., 2016; Poitras & Le Tareau, 2009). Budd and Colvin (2008) provide in this context a triadic framework as a way of extending the assessment of dispute resolution procedures beyond efficiency to include notions of employee voice and equity. In their framework, “efficiency” is considered as the effective use of scarce resources and captures concerns with productivity, competitiveness, and economic prosperity. “Equity” entails fairness in both the distribution of economic rewards (such as equality in wages and benefits) and the administration of employment policies (such as nondiscriminatory selection and promotion processes), and the provision of employee security (such as safety standards and unemployment insurance). “Voice” is the ability to have meaningful employee input into workplace decisions both individually and collectively. While efficiency is a standard of economic or business participation, equity is a standard of treatment and voice of employee participation. Budd and Colvin (2008) state that applying this framework to dispute resolution procedures provides a rich analytical framework in which researchers, practitioners, and policymakers can analyze dispute resolution systems along the dimensions of efficiency, equity, and voice. Considering the previous framework, Saundry et al. (2018) explored how the notions of efficiency, equity, and voice are played out in mediation and assessed the implications for the balance of power within the employment relations. Analyzing the experience of participants in mediation from a variety of contexts at organizational level, they found that mediation is an opportunity for employees as it enhances their access to mediation, facilitates employee voice, and attenuates asymmetries of power inside the mediation room. However, while mediation may have the potential to recast the relationship between participants, they found less evidence to suggest that its use can transform power relationships more widely within organizations. Why Mediation Works? Mediation Promoting Efficiency, Equity, and Voice Mediation is the consequence of the failure to reach an agreement between two parties. The failure of negotiation has a cost both in terms of the relational capital between the parties and in terms of the psychological processes of the individuals themselves. The negotiation impasse led to a distributive spiral, where parties experience negative emotions, develop a negative perception of their counterparts, and the negotiation processes. This failure reduces self-efficacy and willingness to work together in the future, to behave less cooperatively, losing faith in negotiation as an effective means of managing conflicts (O’Connor & Arnold, 2001). Although the conditions under which mediation arises are negative, it has proven to be a very useful conflict resolution tool in order to promote efficiency, equity, and voice in employment relations. Firstly, it provides a context in which the parties can speak freely. In this sense, and in accordance with Budd’s (2004) conception of the effectiveness of labor relations, mediation enables greater direct employee voice. Secondly, in terms of efficiency, mediation is a faster, less costly, and damaging process for the parties, and it is more likely to result in a satisfying outcome than adversarial, win/lose formal procedures. Mediation is desirable in court when parties like to handle their dispute in a relatively inexpensive and fast manner, maintain control over the outcome, and preserve a future relationship with the other party (Goldberg et al., 2017). Thirdly, equality has been traditionally evaluated in terms of ‘fairness’ and the underlying judgements of procedural justice by participants (Shapiro & Brett, 1993). In mediation, the parties agree on the outcome of the process. Authority-driven alternatives, such as judicial procedures, seek ‘best practice’ as defined by law, while mediation seeks ‘discovery of appropriate practice’ in the process. Therefore, taking into account that parties do not prejudge what the process or potential outcomes will be, mediation strategies begin to challenge the social power base of managers (authority) that was used in traditional discipline and grievance processes. Moreover, parties can negotiate in an assisted manner, orienting the agreement towards their own interests. Negotiations oriented toward underlying interests, needs, and wishes of the parties have some advantages related to the quality of agreement and satisfaction with respect to the formal rights-based dispute procedures (Goldberg et al., 2017; Martínez-Pecino et al., 2008). Another aspect of mediation that promotes equity refers to the parties BATNA [best alternative to a negotiated agreement]. Disputants’ beliefs about their BATNA influence receptiveness towards mediation. As stated by Slaikeu (1996), none of the parties will settle in mediation if they have a better BATNA. However, in some cases, BATNAs do not exist as a solid position for a negotiator to use but are based on the beliefs or assumptions of the parties, and are slow or risky options, as is the case with the judicial system. Therefore, parties prefer to use mediation as a tool to resolve their disputes rather than waiting for an uncertain outcome in court. In that sense, mediation is very appropriate for dealing with issues with a little basis for a legal claim (Latreille, 2015, p. 15). For contributions to efficiency, equity, and voice, workplace mediation seems the best conflict resolution approach for dealing with behavioral conflicts between individuals caused by dysfunctional working relationships or communication breakdown (Bennett, 2014). A Structural Analysis of Mediation The study of mediation cannot be approached in a socially neutral setting where all the necessary conditions for mediation are present (voluntariness of the parties, confidentiality, neutrality, and impartiality of the mediators), but requires the consideration of more general aspects, such as the context in which mediation takes place that affects the mediation process (Wall & Dunne, 2012). In that sense, Bollen et al. (2016) suggested a new model of workplace mediation described as the 3R-model (see Figure 1). They build the ‘geometry of workplace mediation’ with the combination of the three dimensions of regulations, roles, and relations. The three dimensions included in the ‘geometry’ aim to capture the comparison of different properties within a three-dimensional space (Budd & Colvin, 2008). The 3-R model proposes a contingency approach where characteristics of regulations, roles, and relations together define the most appropriate design of a mediation system, as well as specifics of the mediation at hand. Together, these three dimensions determine the characteristics of mediation and the results of mediation at different levels. One of the most relevant aspects of this model is that it considers three structural dimensions in mediation, the first of which is “regulations”, particularly to what extent is mediation mandatory to conflicting parties? For collective conflicts, this is a particularly ongoing debate in many countries in relation to the right to social actions, such as strikes. Do parties first have to try to solve their dispute through mediation, or at least a formal attempt to do so, before going to action? In the case of individual disputes, the same dilemma exists: should the parties go to mediation before going to court? In the application of the mediation directive in Europe, four different models are presented (Euwema et al., 2019): a) full voluntary mediation: the parties can engage a mediator to facilitate the resolution of any dispute that they have not been able to settle by themselves – in this case, a mediation legal framework is not even required; b) voluntary mediation with incentives and sanctions: parties are encouraged to attend mediation – this model requires a mediation law in place; c) required initial mediation session: parties are required to attend an initial meeting with a mediator, free or at a moderate fee, to establish the suitability of mediation before any action by parties – this model requires a mediation legal framework; and d) full mandatory mediation: the parties must attend for a full mediation procedure as a prerequisite to going to court, or to take actions such as strikes – the mandatory aspect applies only to attending the full procedure, whereas the decision to reach a settlement is always voluntary. To the extent that the parties are forced to go to mediation, both the mediation process and the potential outcomes will be affected. These four models have been applied differently throughout Europe for many different areas of mediation, showing that the “required initial mediation session” model combines the most effective elements of both the voluntary and the mandatory models. The full voluntariness of mediation occurs in only a few cases (De Palo et al., 2014). The second contextual aspect to consider in mediation is the “roles”: “who” is participating in mediation? Although mediation usually takes place with parties representing themselves, there are many exceptions in the case of more complex disputes, ranging from parties being accompanied by their lawyers, trade union representatives, or simply lawyers negotiating among themselves without the presence of the people they represent. These situations are a challenge for mediators, as negotiations can become multiparty when lawyers’ interests do not necessarily coincide with those of their clients if they have no possibility to reduce their aspirations or if they are less open to mediation than to continue to the court. Research on mediation and law is absent with some exceptions such as Roger’s chapter in Goldberg et al.’s (2017) book. Regarding mediators, it is also possible that, in certain conflicts some people are involved in the management of disputes as well as mediators: legal counselors, union specialists, coaches, or specialized trainers, not to mention different types of leaders, from political (politicians) to societal (mayors, or respected neutral persons), to religious leaders, regularly acting as mediators. This might be particularly the case when the collective labor conflict transforms into societal conflict, as happened recently in Spain with the intervention of the Minister of Labor as mediator in the metal engineering sector conflict in a northern region of Spain. Within organizations, there is also a great deal of diversity, ranging from the existence of ombudsmen/women to ADR systems or nonprofessional mediators belonging from human resources or risk prevention departments. The regulations and role dimensions promote efficiency standard. The findings of Bennett (2014) on mediation in the UK, for example, show the potential of mediation to reduce costs in terms of time and the emotional distress of the disputants going through the formal process, which in the worst case could lead to a costly employment tribunal hearing. The inclusion of emotional distress as a nonfinancial cost is considered a good indicator of efficiency by Budd and Covin (2008), as disputants may suffer psychological costs and disrupt social relations, which, in turn, negatively affect organizational efficiency and individual careers. The third contextual aspect describes the “relations” between the conflicting parties, and with the mediator; ultimately, what is the trust relationship that parties have between them and with the mediation process? Trust can be defined as a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another (Rousseau et al., 1998). The parties must trust the mediators and the mediation system for the mediation to be effective. If trust levels are high, parties in conflict are less suspicious and more enthusiastic to share information with other disputants at the mediation table (Kydd, 2006). Misunderstandings and misinterpretations are likely to appear if a minimum level of trust between the parties is not present in a mediation (Nadler & Liviatan, 2006). It is important to distinguish between the contextual conditions that facilitate the parties’ trust in mediation and the mediators’ own behavior to gain the parties’ trust. In accordance with the first of these aspects, characteristics of mediation (neutrality, impartiality, voluntariness, confidentiality), are a priori guarantee that trust will emerge; however, many mediation systems introduce additional strategies to enhance trust linked to the structure of mediating teams; for example, in some systems, the parties can choose their mediators from a prior list, other systems use relevant community figures as mediators, and, finally, some systems allow the parties to participate directly in the composition of the mediating teams. For example, mediators in the Extrajudicial System for Labor Conflict Resolution (SERCLA) in Andalusia (Spain) are designed by conflict parties (unions and employers’ representatives) as mediators (Medina et al., 2014). A systematic analysis of several mediation systems by Cea et al., (2015) showed that the effectiveness of mediation systems did not depend on the composition of the mediating teams but on the trust that the parties had in the mediation systems. In terms of promoting equity, it is important to consider the structural qualities of the relation, for example, the formal power structure between parties and the legal rights they derive from this. To what extent are parties interdependent and how is the power balance? In some mediations, the parties, mainly represented by their lawyers, have no bargaining power due to national or company regulations; for example, until a few years ago, at the peak of the economic crisis, any salary increase in a Spanish public company, even a local one, had to be approved by the Ministry of Economy itself, which made it almost impossible to reach agreements in mediations in collective conflicts in the public sector; the parties were obliged to go to mediation, but the session was completely dysfunctional. There is an important debate going on about how to improve the mediation procedures to increase trust between the parties. The union side believes that often the employers’ side attends mediation with little interest in negotiating or gives the lawyers representing them very strict instructions, so they leave little room to reach satisfying agreements for both parties (Euwema et al., 2019). At the same time, it is important to take stock of the psychosocial qualities of the relationship, given that most labor relations are more than just instrumental. How do the parties perceive each other? To what extent do they wish to reconcile? What is their attitude: cooperative or competitive? To what extent do they perceive justice? Both structural and interpersonal characteristics will determine what type of mediator, strategy, and tactics are used best to come to a mutually acceptable and satisfying solution (Euwema et al., 2019). In search of an Evidence-based Approach for the Use of Mediation in the Workplace Despite the increased promotion and implementation of mediation, as a primary dispute resolution process, there is a general agreement in the literature and systematic reviews on the topic on the need for a closer link of mediation practice with evidence-based research (Bennett, 2014; Bollen & Euwema, 2013, 2015; Coleman et al., 2016; Euwema et al., 2019; Wall & Dune, 2012). As Dolder (2004) states: "Somewhat surprisingly, the lack of research on the realities of mediation practice has not deterred policy makers from facilitating the movement away from tribunal-based disputes resolution" (p. 321). Therefore, there is a tendency to rely on fragmented research on the topic and anecdotal evidence regarding mediation’s success in achieving agreements, and the beneficial impact of mediation in working relations, to persuade organizations and individual disputants to accept prescriptive workplace mediation services (Dolder, 2004). Only in the beginning of the 1990s there was some fragmented research on the role of third parties in nonjudicial dispute resolution settings (Brett & Goldberg, 1983; Conlon & Ross, 1993; Karambayya et al., 1992; Kolb, 1986; Lewicki & Sheppard, 1985; Prein, 1984; Shapiro & Brett, 1993; Ury et al., 1993). The weaknesses indicated in this direction have promoted relevant contributions in recent years towards the development of theoretical frameworks that move beyond descriptive models and practical settings and are oriented towards systematically building on comprehensive empirical findings that could offer valid, predictive insights into effective practice under different mediation conditions (Bollen et al., 2016; Coleman et al., 2016; Goldberg et al., 2017). A recent series promoted by Springer in Industrial Relations & Conflict Management represents this effort by trying to integrate theories and research from industrial relations with those on conflict management and mediation. The series respond to the demands of policymakers, researchers, and dispute resolution practitioners to promote evidence-based frameworks and models of mediation efficiency and effectiveness. For a compilation of these current contributions to mediation, both in individual workplace conflict and in collective labor conflict intervention, see Advancing workplace mediation through integration of theory and practice, by Bollen et al. (2016) and Mediation in collective labor conflicts, by Euwema et al. (2019), included in the Springer series. Contributions from this perspective recognize that evidence-based mediation is a constructive way to deal with conflict and an essential element in setting up a conflict management system in organizations (Kalter et al., 2018). It helps organizations create effective and efficient procedures to deal with conflicts in a positive way that contributes to a healthy work climate (Bollen & Euwema, 2015; De Dreu, 2008; Dijkstra, 2006; Giebels & Janssen, 2005). At the same time, as previously indicated in this study, mediation cannot be seen as panacea to all workplace conflicts between employees (Jordaan & De Wulf, 2016). There will be situations in which mediation is less suitable or a judicial procedure is the only option. For example, in the case of workplace bullying or sexual harassment, some authors argue mediation is not in the interest of the victim nor in the interest of organizations (Jenkins, 2011; Olsen, 2012), and can only be appropriate under certain circumstances (Lempp et al., 2020). Therefore, workplace mediation should be part of a broader conflict management system (Brinker, 2016; Jones, 2016) in which conditions are stipulated for which mediation may work best or may be most effective. The recognition of this idea brought a surge in both researchers’ and practitioners’ interest to ponder on the question which mediator strategies and behaviors should be used in different situations to be most effective (Coleman et al., 2014; Wall & Dunne, 2012). This calls for a contingency approach to workplace mediation, more specifically, what new developments of workplace mediation could be promoted to increase mediation effectiveness? what are the most effective ways of mediation given certain situations? and how to integrate workplace mediation in a broader system of conflict management resolution? The first issue to address in this direction refers to the establishment of evidence-based standards for the assessment of mediation intervention. The inclusion of the equity and voice standards together with the traditional efficiency standard allows one to move forward in this direction. In turn, the consideration of the structural dimensions of the mediation context, such as regulations, roles, and relations, underpinned a contingent approach to mediation practice. Together with these relevant variables, evidence-based contributions related to dynamic conflict and mediator strategies and adaptive behaviors can enrich this contingent approach to the effectiveness of mediation intervention. There is evidence on the appropriateness of mediation according to: a) what is the intensity or escalation level of the conflict, b) how to use mediation to manage different types of conflict, and c) what strategies and tactics could be used to increase the effectiveness of mediation (see Figure 2). Conflict Intensity Mediation has proven to be contingent on the intensity of the conflict or the level of escalation of the conflict (Coleman et al., 2016; Euwema et al., 2019). Escalation is the process of intensification of a conflict using harder tactics by parties, increasing issues and parties, and modifying the motivations of the parties from realizing their own interest to hurting the other (Rubin et al., 1994). Gasl (1997) in his well-known conflict escalation model, proposes that mediation is functional when used at a medium level of conflict escalation. Euwema et al.’s (2019) research on mediation in collective conflicts proposes a model of conflict development in five phases: 1) latent content, 2) early stage, 3) confrontation, 4) hot conflict, and 5) rebuilding relationships. Evidence suggests that mediation is used mainly in stages 3 and 4 in organizational conflicts (see Figure 3). Research by Euwema et al. (2019) offers information on the positive use of preventing mediation to improve the effectiveness of conflict in an early stage of the conflict (facilitating the negotiation process, for example). At the same time, after a conflict episode, the use of mediation to reconcile parties is a great challenge because the aftermath of the conflict will fuel the next cycle of conflict. How to reconcile the parties after the conflict episode and how to generate a positive organizational environment is crucial, especially in cases of high conflict intensity where relations between the parties have deteriorated. Conflict Types and Mediation Employment relations are a hybrid between two scientific and professional areas, labor relationships and organizational psychology, with different perspectives and conceptual framework. The level of development of research on conflict types has been greater in the field of organizational psychology than that produced in the field of labor relations, so that some authors consider that the practice of workplace mediation is underpinned by the view of conflict that it is "mostly interpersonal or a product of organizational dysfunction" (Budd & Colvin, 2014, p. 23). Each of these disciplines has developed typologies to address the conflicts that take place within organizations. The first important distinction to make is between collective and individual conflicts. Collective labor conflicts traditionally are focusing on the relation between management and groups of employees, mainly associated in unions. This differs from individual disputes, which are those that arise within the relationship between an individual employee and his or her employer or colleagues due to a miscommunication problem or different interests. The widely accepted typology of team conflict by Jehn (1995), task, process, and relationship conflict, nicely captures the dynamics of interpersonal conflict in teams (e.g., Benitez et al., 2012). Task conflict is a perception of disagreement among group members or individuals about the content of their decisions, and involves differences in viewpoints, ideas, and opinions. Examples of task conflict are conflicts about the distribution of resources, about procedures or guidelines, and about the interpretation of facts. Relationship conflict is a perception of interpersonal incompatibility and includes annoyance and animosity between individuals. Examples of relationship conflict are disagreements about values, personal or family norms, or about personal taste. Process conflict consists of disagreements over procedures or methods that the team or group should use to complete its tasks. Bendersky and Hays (2012) recently introduced the term status conflict, defined as disputes over people’s relative status positions in their group’s social hierarchy. The aforementioned conflict types allow us to understand the interpersonal disputes in the organization; however, they do not allow us to comprehend the conflicts that workers and their companies have that are caused by issues discussed in employment relationships such as salary, vacations, or the number of hours worked (Elgoibar et al., 2021). In this sense, the labor relationship field distinguishes between interest-based conflict and right-based conflicts (Martínez-Pecino et al., 2008). On the one hand, interest-based conflicts refer to those conflicts that pertain to the establishment of the terms and conditions of employment. An example might be the negotiation of a salary, or the numbers of days of vacations per year. On the other hand, right-based conflicts refer to the application and interpretation of a previously established norm or law are about discrepancies entitlements incurred or legal considerations. Examples of this situation are when a complaint is presented by a worker, denouncing the violation of a rule (for example, risk prevention rules), gender issues, or disciplinary codes. On this occasion, the employee may claim that his or her rights as a worker have not been respected and there may also be circumstances in which management may claim that its rights have not been respected (Table 1). Evidence suggests that mediation is much more effective in individual conflicts than in collective conflicts (Medina et al., 2014). At the same time, the agreement rate is higher in interest-based conflict than right conflicts (Medina et al., 2014). Using the basic elements of negotiation, the types of dispute in which the parties focus on their rights and legal considerations are often associated with zero-sum results in which there is a winner and a loser. In these cases, mediation is less effective than in issues with an integrative potential. When the parties are locked into rigid positions for what they believe to be ‘right’, there is little to trade and this may make them prefer courts to mediation (Medina et al., 2014). That rationale explains why agreement rate in right-based conflict is about 40% on average while the agreement rate for interest-based conflicts is 20 points higher (Medina et al., 2014). Rights conflicts, compared to conflicts of interest, tend to be more legalistic and adversarial, and the parties could prefer to go to the courts instead of searching for an agreement in mediation. Similarly, collective conflicts are more difficult to manage than individual conflicts for different reasons: a) the negotiators represent the constituents, which adds a second negotiating table that has to establish the agenda and ratify the agreements, b) workers are usually represented in several unions with different interests, so it becomes a multiparty mediation, with the emergence of coalitions and greater difficulty for integrative agreements, and c) group processes such as polarization or the emergence of more violent tactics make the process more difficult. With respect to interpersonal conflicts, task or process conflicts do not have a high level of escalation, and the parties usually reach agreements between them without a third-party help, so mediation is not usually used to deal with these conflicts; however, mediation could be useful to manage relational conflicts. Status conflicts have a high potential for escalation since they generate very competitive situations between people who are disputing for a hierarchical position. Although there is no evidence of the use of mediation in this type of conflict, according with literature (Pai & Bendersky, 2020) we understand that this is a type of conflict where mediation could be very useful. It is a research question to be developed in the future. Mediation Strategies and Tactics Related to the contingency approach of mediation, it is important to consider strategies, styles, and behaviors of the mediator. In this sense, Kessell’s typology (developed by Lim & Carnevale 1990) distinguishes between reflexive (i.e. promoting trust), contextual (i.e. managing the process), and substantive strategies (i.e. pushing parties actively to an agreement). Contextual strategies try to facilitate the process of conflict resolution by modifying the circumstances in which mediation occurs. The mediator does not seek to directly address the issues of the conflict, but facilitates the process to make the parties themselves reach their own solution. Examples of this type of intervention are to simplify the agenda, prioritize the issues, etc. Substantive strategies refer to interventions that directly cover the topics of conflict in the search for an agreement. Some examples of this type of intervention are trying to change the positions of any of the parties, making a suggestion of agreement, etc. Finally, reflexive strategies try to steer the third party toward the conflict, to win acceptance by the parties, establishing trust in the third party and the mediation process, and create a basis for the development of the future activities. Some examples of this type of intervention are developing trust with the parties and use humor to relax the atmosphere. Martínez-Pecino et al. (2008) demonstrated a difference in the effectiveness of these strategies, depending on the type of dispute. Contextual and substantive strategies are positively related to settlement in both rights and conflicts of interest. However, the effectiveness of reflexive strategies varies depending on whether the conflict is a conflict of interests or a rights conflict. Specifically, an increase in the use of reflexive strategies is negatively related to the general settlement outcome, particularly in rights conflicts. At the same time, Grima and Trepo (2009), in a field study about mediation in France, suggest that mediators adapt their behavior to the conflict level, being very active in their use of pressure tactics, not only forcing disputants to reduce aspirations but also pushing aside any actors that are a barrier to the agreement, when parties are in an impasse, showing positive results. A different typology is used to identify mediation styles (Kressel, 2014). A style is a general approach pursued with mediation, e.g., achieving agreement, improving relations between the parties, or improving the parties’ skills in managing their conflicts. These styles are facilitative, evaluative, settlement, and transformative. Contrary to what happens in other contexts where mediation is used, reaching an agreement is a priority in the workplace over other outcomes. The consequences of a labor dispute for the parties and the organization, especially when there is a threat of strike or judicial processes, make settlement a priority over other mediation outcomes like empowering parties or improving relationships. For that reason, data suggest that mediators use the problem solving/settlement approach more than a transformative and facilitative approach, and the problem solving approach to be more effective in labor contexts (Kenny, 2019). However, certain styles may be effective in some situations, but detrimental in others. For example, a problem solving approach may facilitate a quick but short-lived agreement when relations between the parties are very damaged, whereas a more transformative mediation could help reconcile relations between the parties and facilitate a more stable and lasting agreement as a result. In fact, some authors propose the notion of ‘stylistic eclecticism’, where the mediator moves between styles during or between mediations (Curran et al., 2016). The mediation process is also used contingently by mediators. Mediators may choose to keep the parties in the same room for the entire process or separate them into separate rooms (caucus). Joint sessions are useful for the parties to feel listened to in a safe environment, allow mediators to gain an understanding of the situation, and demonstrate their impartiality and control of the process. Private sessions are useful to understand the real interests of the parties, to test settlement options that would have emerged in joint sessions, or to test the parties’ position against their own reality. Deciding when to use private or joint sessions is a necessary competence for mediators, which could improve the likelihood of resolving disputes if they use these meetings to increase procedural justice in hierarchical conflicts, manage negative emotions, and build trust with the mediator (Bollen et al., 2012). Another possibility is to meet the parties separately prior to the mediation itself, called a precaucus. When relations are very damaged, it helps to hold a meeting with each party beforehand; these meetings can be useful for mediators in getting to know the parties’ readiness for mediation, their initial positions, or their BATNA. However, these precaucus meetings are more effective if they focus on emotional aspects, such as encouraging the parties to mediation or managing their negative emotions, than if they are used for substantive discussions about the nature of the conflict (Swaab, 2009). However, empirical evidence on the use of precaucus in complex conflicts is scarce and is a line of research that deserves to be explored in the future. Mediation is increasingly used to solve labor conflict in a nonjudicial way, preventing costly, lengthy, and unsatisfying legal procedures. Mediation as a way of constructively dealing with conflicts is an essential element in setting up a conflict management system in organizations or an organizational dispute system. It helps organizations create effective and efficient procedures to deal with conflicts in a positive way that contributes to a healthy work environment. Mediation deals with delicate and complex issues, where confidentiality is one of the basic principles, so empirical evidence based on systematic and experimental studies is very scarce, and research on mediation is a challenge for the scientific community, especially what happens within the mediation process itself. Contrary to what happens with negotiation, where there is a huge amount of field and experimental research, scientific evidence about mediation nowadays is partial and a systematic analysis is practically anecdotal. Added to this is the difficulty that mediation must be understood within a legal context. Existing research suggests that mediation must be contingent. In this sense, it is important that we develop these contingencies in the future: what process, strategies, or tactics should be used for each type of conflict and its intensity? It is also necessary to develop the limits of mediation as a conflict resolution tool. Despite the advantages of mediation and its potential to achieve efficient, equitable, and participatory labor relations, mediation is not a panacea for all types of workplace disputes, especially in those situations where the parties claim a sense of justice for being wronged. One of the key aspects of the paradox of mediation refers to the lack of critical dimensions to evaluate dispute resolution systems beyond speed, satisfaction, and acceptance of possible solutions by disputants. The objectives of efficiency, equity, and voice described in this paper provide rich standards for evaluating mediation effectiveness. The combination of the dimensions of regulations, roles, and relations enshrined in the ‘geometry of workplace mediation’ provides a contingent approach to the design of optimal and effective workplace mediation systems depending on the specific society, industry, and organization. The 3-R model of workplace mediation is well situated as a conflict management and resolution system for the promotion of efficiency, equity, and voice standards. This model can also be used to focus the orientation of scholars, practitioners, and governments in looking for new developments in the design of workplace mediation. In this sense, future research could explore specific combinations of these dimensions that best fit specific sectors, organizations, or cases of mediation. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Funding: This project was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. Project I+D (Ref. PID2019-110093GB-I00) and by I+D+i FEDER Andalucía 2014-2020, (Ref. US-1380796). Cite this article as: Munduate, L., Medina, F. J., & Euwema, M. C. (2022). Mediation: Understanding a constructive conflict management tool in the workplace. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 38(3), 165-173. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2022a20 | Introduction The Use of Mediation in Labor Settings Criteria for Mediation Effectiveness: Promoting Efficiency, Equity, and Voice Why Mediation Works? Mediation Promoting Efficiency, Equity, and Voice A Structural Analysis of Mediation In search of an Evidence-based Approach for the Use of Mediation in the Workplace Future Lines of Research |

Cite this article as: Munduate, L., Medina, F. J., & Euwema, M. C. (2022). Mediation: Understanding a Constructive Conflict Management Tool in the Workplace. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 38(3), 165 - 173. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2022a20

fjmedina@us.es Correspondence: fjmedina@us.es (F. J. Medina).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS