A Systematic Review of Evidence-based General Competency Models: Development of a General Competencies Taxonomy

[Una revisiĂłn sistemática y sĂntesis de modelos de competencias generales basados en la evidencia: desarrollo de una taxonomĂa de competencias generales]

David Arribas-Aguila1, 2, 3, Gloria Castaño2, and Rosario Martínez-Arias2

1Hogrefe TEA Ediciones, Spain; 2Complutense University of Madrid, Spain; 3CES Cardenal Cisneros, Madrid, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2024a6

Received 14 February 2024, Accepted 3 June 2024

Abstract

The purpose of this research was to develop a taxonomy of competencies common across different jobs, occupations, and organizations. To achieve this objective, a definition of competency was constructed and a systematic literature review was conducted, selecting studies that: a) included models with general competencies conceptually close to such definition, b) belonged to the Work and Organizational, and Employability areas, and c) were supported by one or more sources or empirical data. Through this procedure, 23 lists of general competencies were identified, whose content analysis, with a high degree of agreement between two independent reviewers, led to a taxonomy of 36 competencies containing the elements common to all of them. This taxonomy of general competencies is a resource intended to assist in the development of new models and serve as a reference for future competency modeling processes related to the work context.

Resumen

Este trabajo se propuso elaborar una taxonomía de competencias transversales a distintos puestos, organizaciones y ocupaciones. Para alcanzar este objetivo, se construyó una definición de competencia y se llevó a cabo una revisión sistemática de la literatura, seleccionando estudios que: a) incluían modelos con competencias generales conceptualmente próximas a dicha definición, b) pertenecían a los ámbitos del Trabajo y las Organizaciones y de la Empleabilidad y c) se basaran en datos empíricos procedentes de una o varias fuentes. Mediante este procedimiento, se identificaron 23 listados de competencias generales, cuyo análisis de contenido, con un elevado grado de acuerdo entre dos evaluadores independientes, permitió elaborar una taxonomía de 36 competencias con los elementos comunes a todas ellas. Esta taxonomía de competencias generales supone un recurso que pretende facilitar el desarrollo de nuevos modelos y servir de referencia para futuros procesos de modelado de competencias relativos al contexto laboral.

Palabras clave

Modelo de competencias, Modelado de competencias, Competencias generales, Empleabilidad, RevisiĂłn sistemática, TaxonomĂaKeywords

Competency model, Competency modeling, General competencies, Employability, Systematic review, TaxonomyCite this article as: Arribas-Aguila, D., Castaño, G., & Martínez-Arias, R. (2024). A Systematic Review of Evidence-based General Competency Models: Development of a General Competencies Taxonomy. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 40(2), 61 - 76. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2024a6

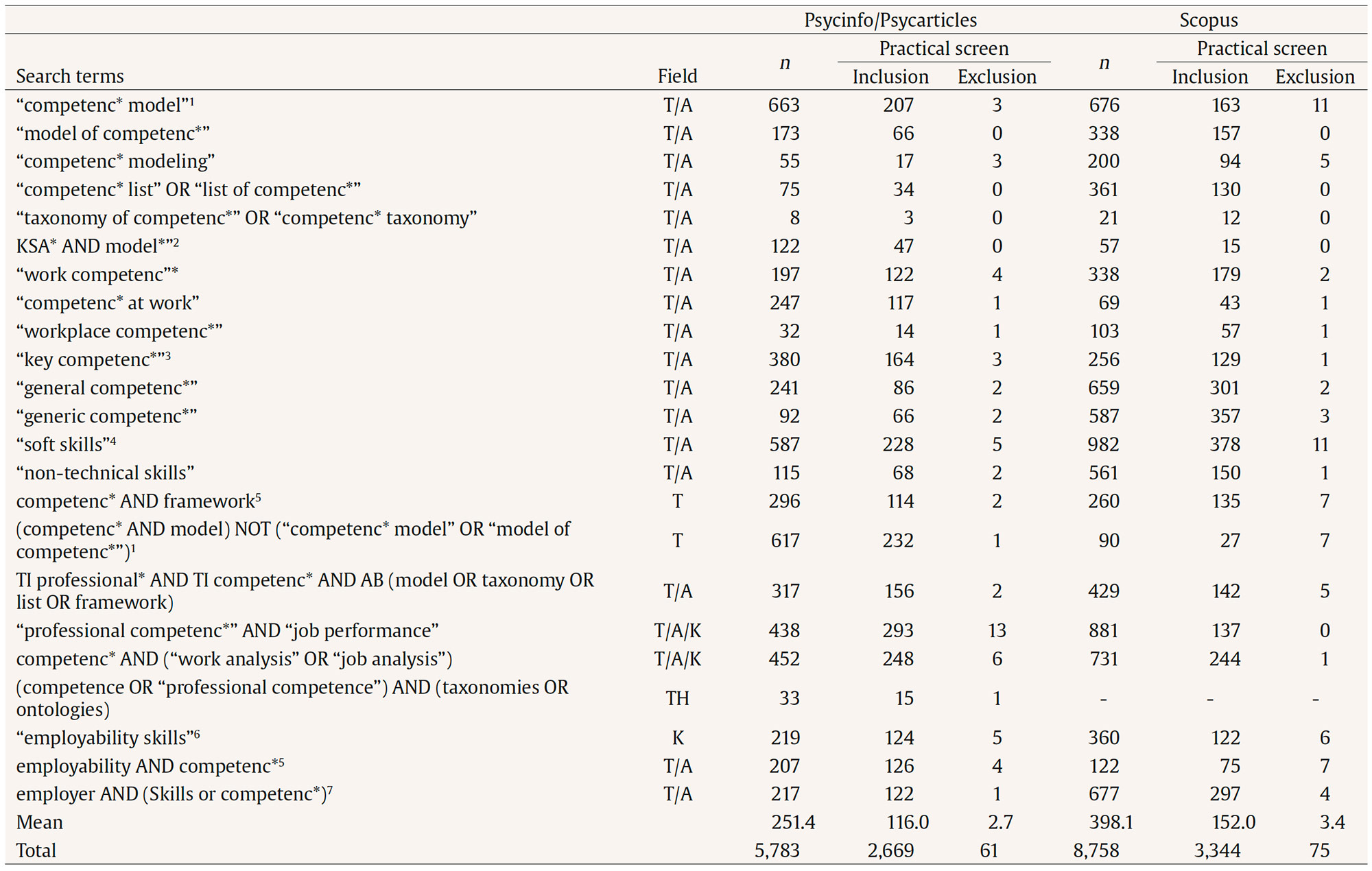

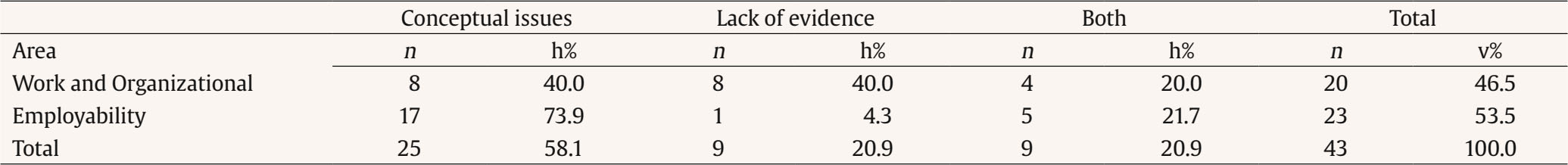

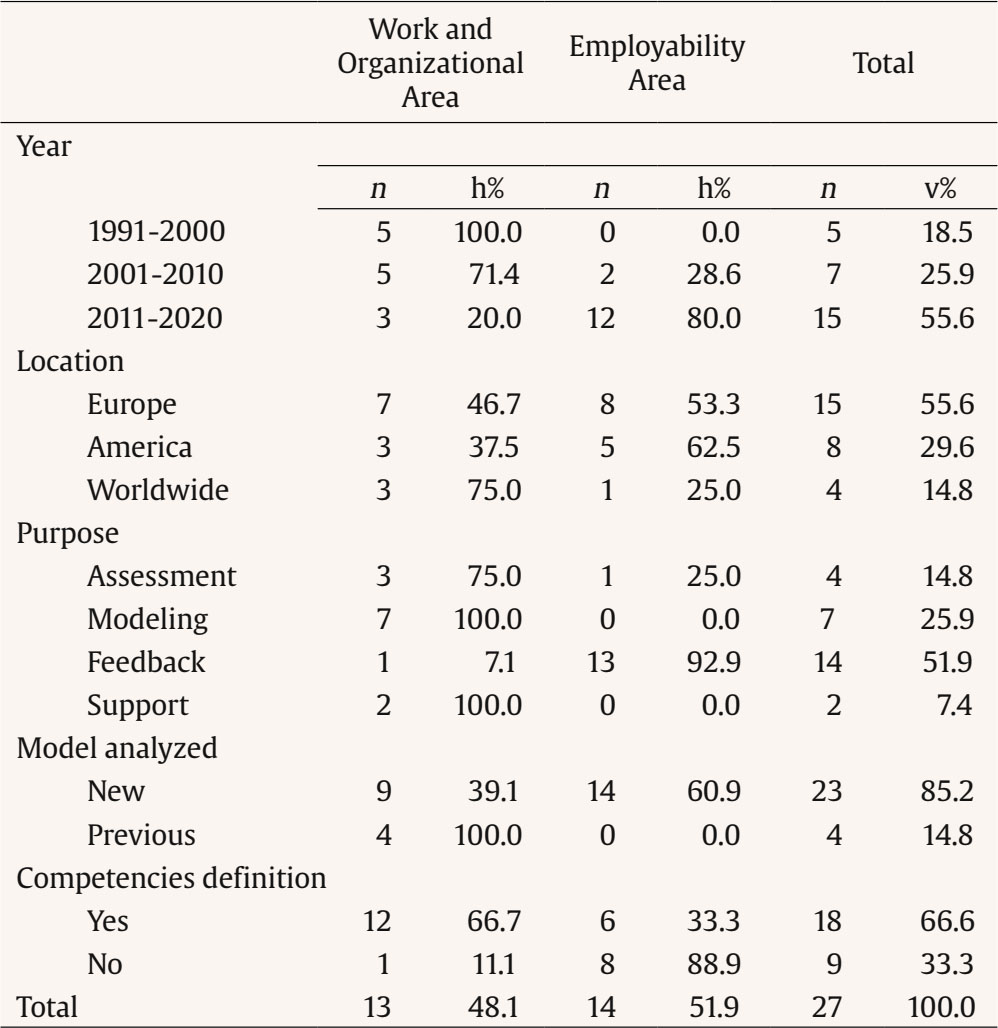

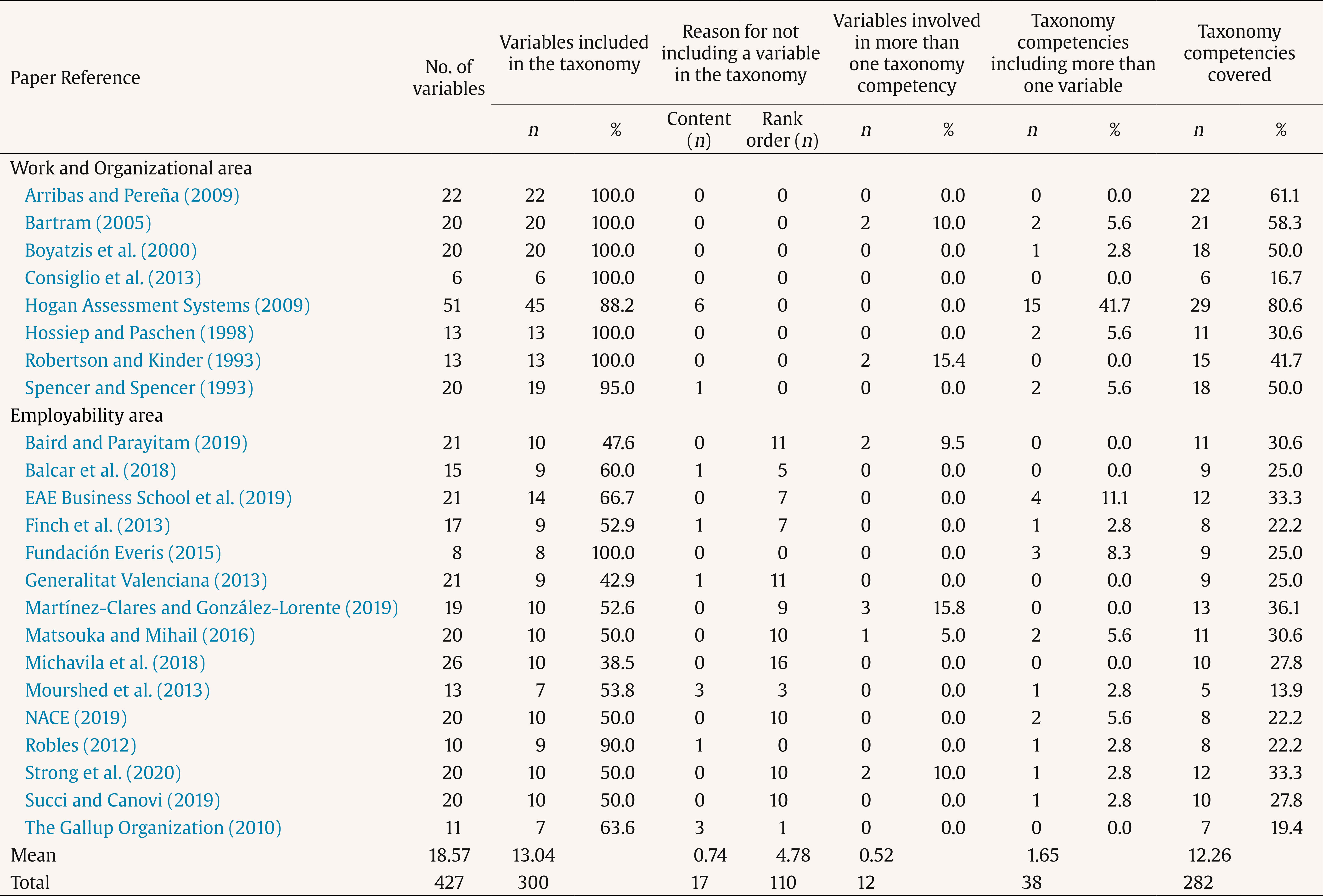

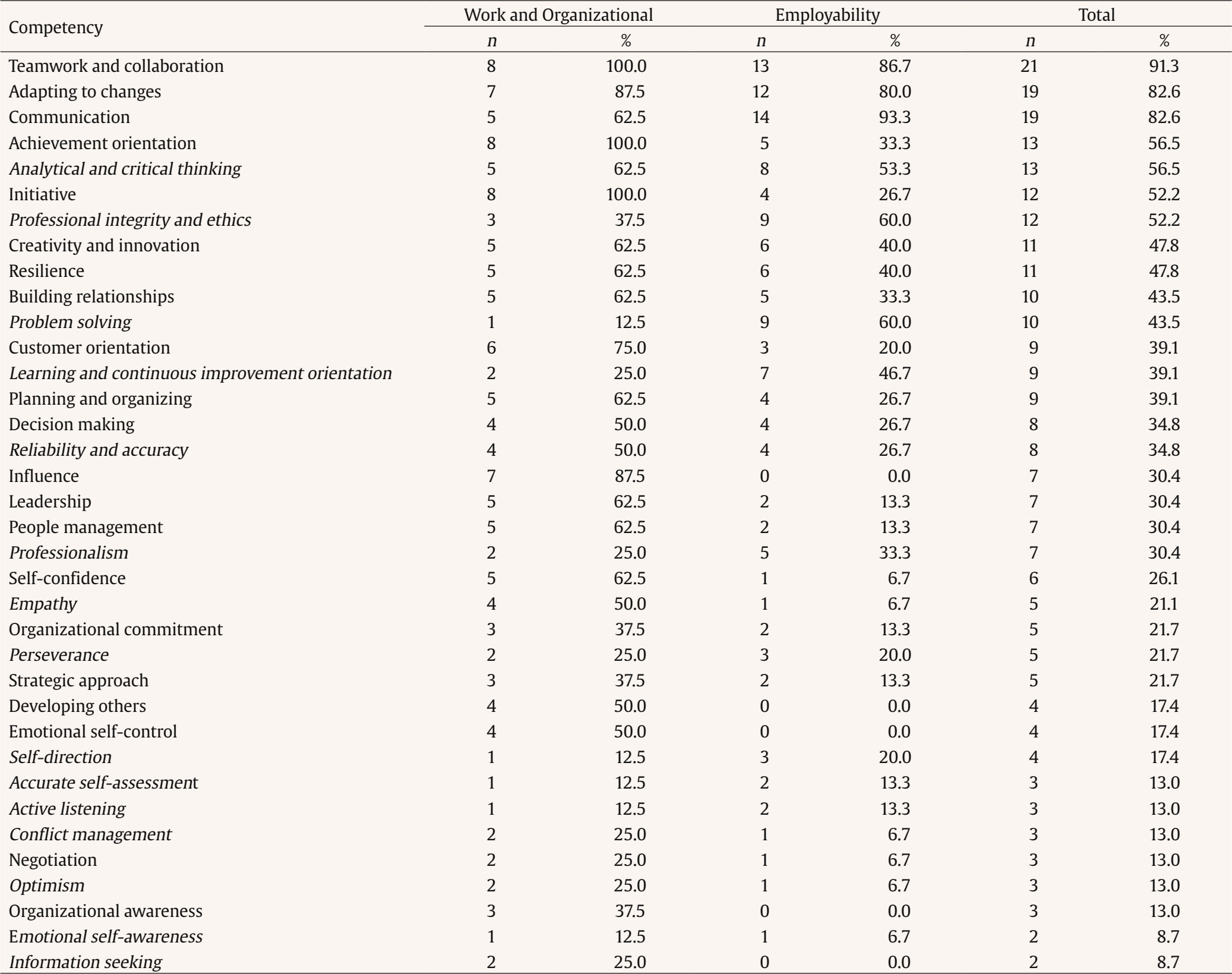

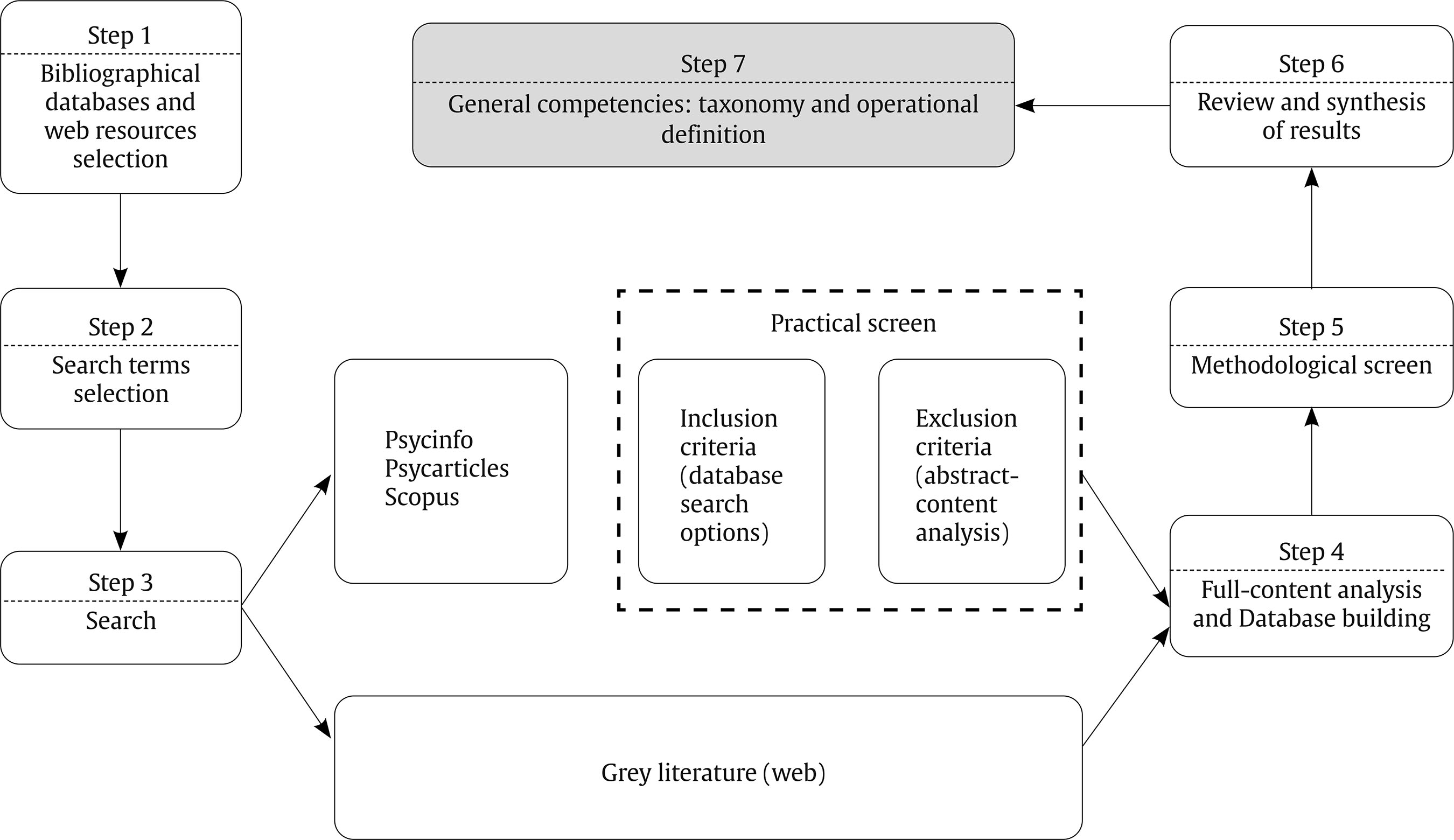

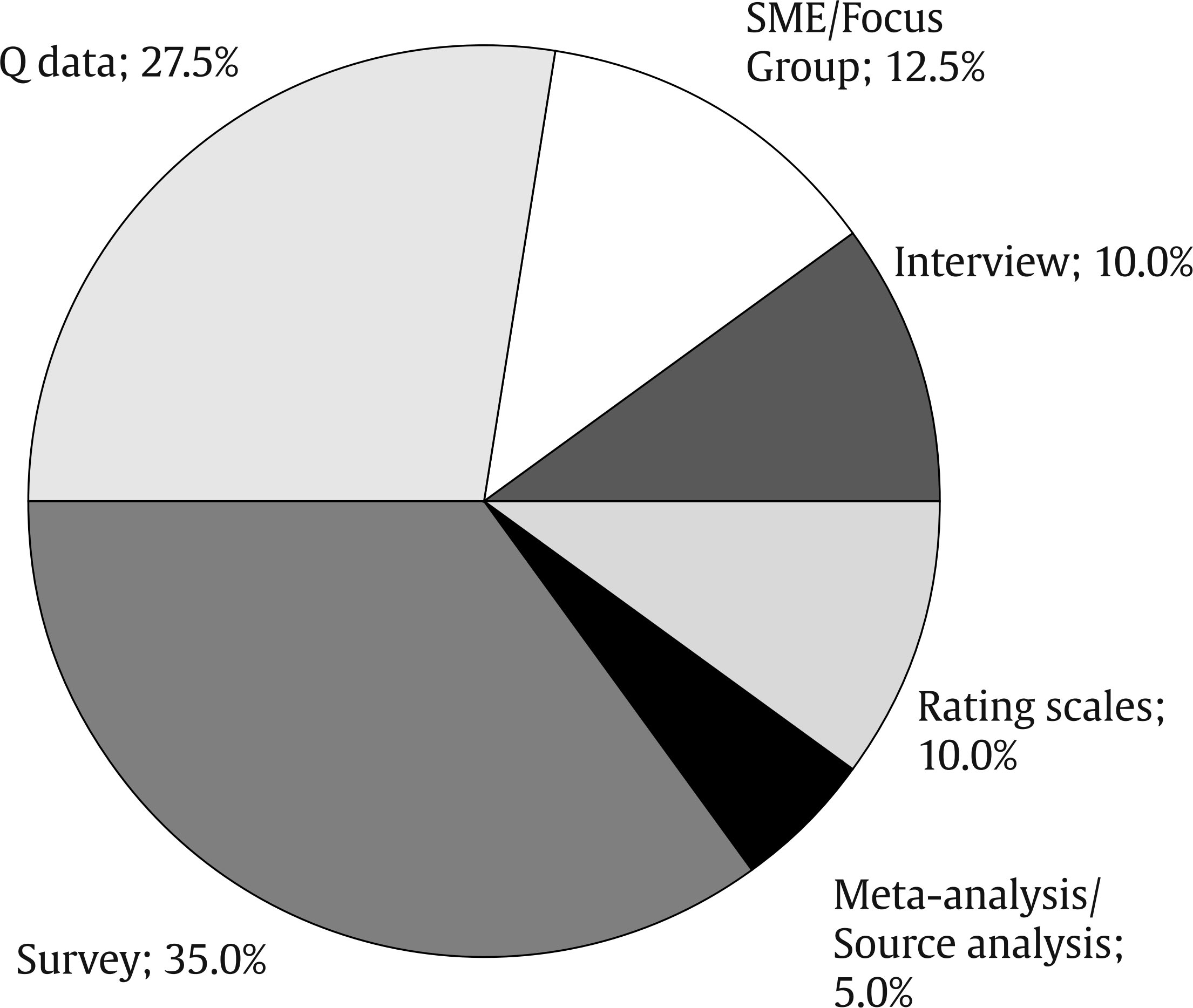

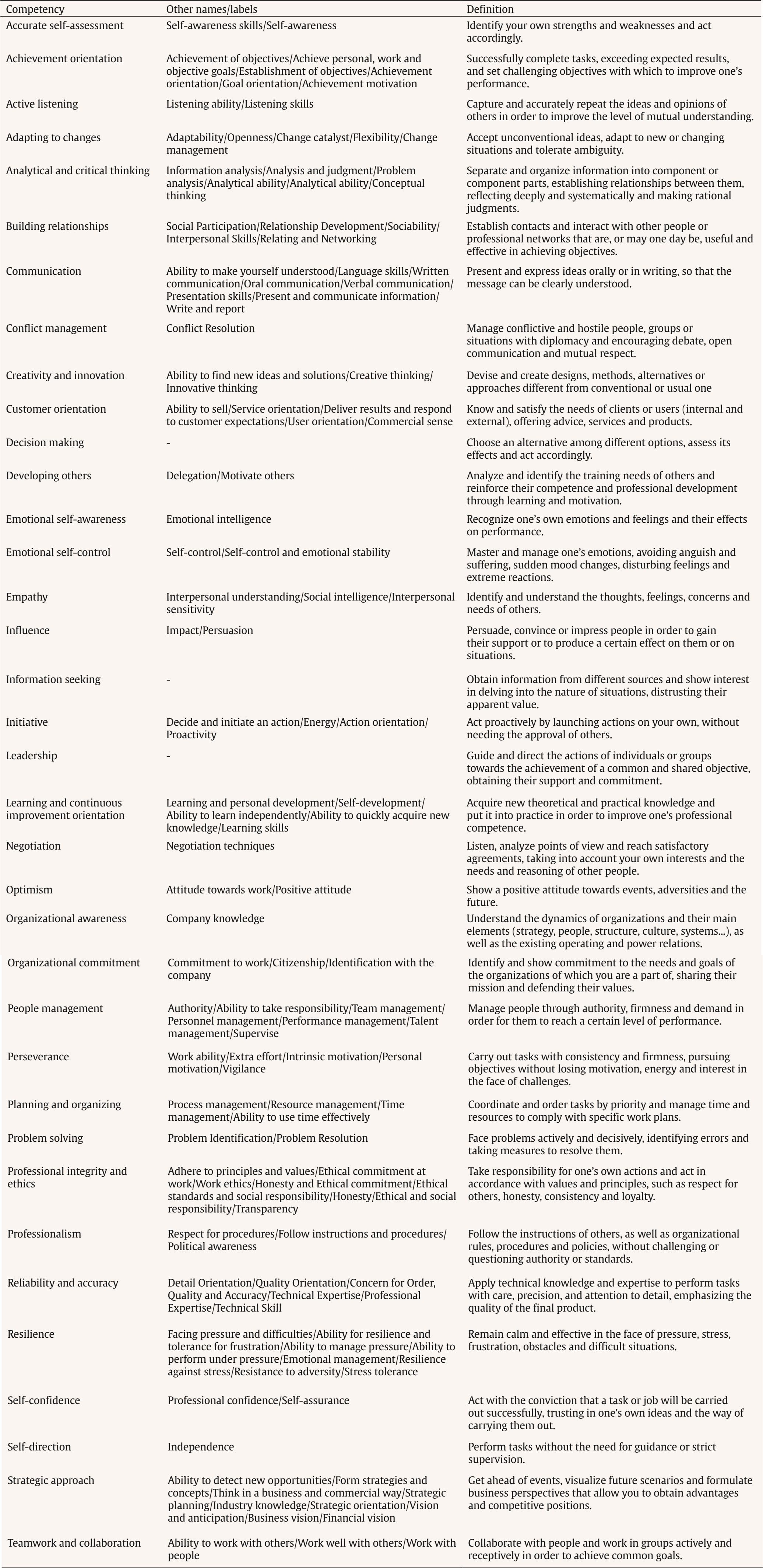

Correspondence: david.arribas@hogrefe-tea.com (D. Arribas-Aguila).After more than half a century of what can be considered the birth of the competency movement (McClelland, 1973), the state of the art of the competency concept remains a controversial issue. From a terminological point of view, the coexistence of two terms, “competence” and “competency”, which are related enough to create confusion, but also distant enough to generate debate, is of little help. Although from the beginning “competence” preferably referred to the functional demands of the job (tasks, standards, qualifications, requirements) and “competency” to a more psychological concept linked to the attributes of the individuals who perform that job (Kurz & Bartram, 2002; Mansfield, 2004; Weigel et al., 2007; Winterton, 2009; Woodruffe, 1992), the use of one or another term to refer to each view is something that has not occurred systematically (Le Deist & Winterton, 2005; Teodorescu, 2006). From a theoretical perspective, competencies as psychological attributes continue to be unclear concepts in comparison to others within the Work and Organizational Psychology field, currently lacking a framework that successfully integrates the numerous approaches that have emerged to date. Furthermore, we still do not have an agreed definition to serve as a reference, an absence that is considered one of the most tense and difficult issues in business research (Vazirani, 2010). For this reason, and despite being a task seen by some authors as uncomfortable or even vexing (Morgeson et al., 2004), it is essential to begin by explicitly clarifying the concept of competency that will be used as a reference in this study. Definition of Competency Although it is possible to identify common elements in many of the definitions of competency used in the field of Work and Organizational Psychology, such as its global nature (Gangani et al., 2006), its emphasis on observable behaviors (García-Sáiz, 2011; Heinsman, 2008; Pereda & Berrocal, 2011) or, especially, its relationship with job performance (Bartram, 2005; Campbell & Wiernik, 2015; Stevens, 2013; Tett et al., 2000), there continues to be no definition of competency that is unique, absolute, true, and integrative. This objective, the most common under the objectivist approach (Yeaman et al., 1996), has proven to be unfruitful to date, with more efforts having been invested in highlighting the problems associated with the lack of consensus than in other issues of a more practical and applied nature (Op De Beeck & Hondeghem, 2009). In contrast, more than twenty years ago, Stoof et al. (2002) proposed the Boundary Approach of Competence, a constructivist approach that admits the coexistence of multiple definitions of competency, all of them equally valid. The criterion used by this approach to judge a definition is not the search for an absolute truth, but rather its adaptation to the context in which it will be used, that is, its viability. The objective, therefore, is not to try to describe in detail a concept as extremely broad and diffuse as that of competency (Klink & Boon, 2003), but to focus on the construction of a definition that is viable and that responds to real situations and needs. For the construction of any definition of competency, the constructivist approach considers it necessary: a) to take position on five dimensional axes related to competency (or “competence”, as it is referred to in their paper), i.e., personal vs. task characteristics, individual vs. distributed competence, specific vs. general competence, levels of competence vs. competence as a level, and teachable vs. non-teachable competence; and b) to delimit the scope of competence in relation to other related constructs, such as performance, ability, or qualification, among others (Stoof et al., 2002). Following this scheme, the definition constructed for the present study understands competencies as homogeneous sets of behaviors that are a consequence of an individual’s knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics (KSAO), and which are directly identified with an outstanding level of overall performance or any of its dimensions (Salgado, 2017, 2019): task performance, contextual performance, counterproductive work behavior, and/or creative and innovative performance. General Competency Models Despite the conceptual limitations noted above, competencies have attracted enough interest in organizations to become an essential resource on which to support their human resource management policies (Baczyńska et al., 2016; Goldman & Scott, 2016; Lievens et al., 2010). This interest has led to the proliferation of taxonomies whose main purpose is to identify the characteristics that are related to effective performance: they are the so-called competency models. Thus, a competency model is nothing more than a collection of characteristics and behaviors that are needed for effective performance on the job (M. C. Campion et al., 2019), an operational way of organizing lists of competencies detailing the relevant components for job performance. Many of the competency models used by organizations today are developed internally by the organizations themselves (Harper, 2021; Schippmann et al., 2000), which makes the generalization required for an evidence-based practice very challenging. Generally, these types of models belonging to the professional/applied field: a) refer to specific positions within the organization, usually management roles, which reduces their degree of generalization and applicability to all hierarchical levels of the company (Skorková, 2016); b) are the exclusive property of the organizations, which limits their divulgation and availability (Aguado et al., 2008); and c) are usually based on the experience of the practitioner who develops them, which makes their replicability and use in research difficult (M. A. Campion et al., 2011). A more suitable framework for research is found in the models from the research/academic field that are published in specialized literature (Heinsman, 2008; Ones & Viswesvaran, 1996). These types of models mainly focus on entire job categories, especially from the management area (e.g., Batista-Foguet et al., 2017), and on large groups of occupations belonging to broad professional sectors (e.g., Bouley et al., 2015; Campos et al., 2017), with some less frequent models focused on more global levels, such as those of the US civil service (e.g., Rodriguez et al., 2002) or even the global workforce (e.g., Arribas & Pereña, 2009; Kurz & Bartram, 2002). From a conceptual view, the idea underlying this type of models or global resources (also called competency libraries or dictionaries) is that there are competencies that can be common across jobs, organizations, and occupations, which consistently appear in the literature under the same label and that are able to explain some percentage of the variance of job performance (Dulewicz & Herbert, 2002; Furnham & Mansi, 2011; Ryan et al., 2012; L. M. Spencer & Spencer, 1993; S. M. Spencer et al., 2008). As M. A. Campion et al. (2011) pointed out, “certain competencies are universally important to certain job types, they are stable over time (i.e., they remain important despite internal and external changes), and there is considerable overlap (around 80%) between models implemented in most organizations for similar positions” (p. 246). However, several authors have suggested that these types of general models and the common competencies they include have some limitations. The main one is that they often have limited empirical support, greater than that of models belonging to the professional/applied field, but not enough for an evidence-based practice (Boyatzis, 2008, 2009; Heinsman, 2008; Kurz et al., 2004; Lievens et al., 2004; Stevens, 2013; Tett et al., 2000). Also, most of them were developed decades ago (e.g., Boyatzis, 1982; Kurz & Bartram, 2002; L. M. Spencer & Spencer, 1993), which implies that their degree of adequacy to the current organizational needs and reality remains unknown. Regarding common or cross-jobs competencies, some authors consider that they are imprecise and irrelevant constructs for capturing the unique capabilities that organizations demand, precisely due to their high degree of generality (Cheetham & Chivers, 1996; Markus et al., 2005; Megahed, 2018; Stasz, 1997; Woodruffe, 1992). Others even doubt their existence, considering that they vary not only between occupations but also from one position to another within the organization itself (Gonczi, 1994; Lucia & Lepsinger, 1999; Pereda & Berrocal, 2011). Finally, other authors highlight a terminological issue: the fact that two competencies use the same name or verbal label does not mean that they are truly equivalent to each other (Antonacopoulou & FitzGerald, 1996; Le Deist & Winterton, 2005; Mansfield, 2004). In summary, there is a notable gap between the research/academic field and the professional/applied field regarding competency models: research is not providing the support that organizations require or a clear, useful, and direct response to their needs and requests (M. A. Campion et al., 2011; Furnham, 2018; Nikolaou, 2003; Schippmann, 2010; Soderquist et al., 2010; Stone et al., 2013). Competency Modeling Competency modeling (CM) is a step-by-step process that results in a competency model and that identifies the characteristics needed for effective performance in some or all jobs in an organization (M. A. Campion et al., 2011; Schippmann et al., 2000). Since its origin, CM was seen as an improvement of job analysis (JA) practices, although the correspondence between one method or the other remains a controversial issue (Lievens & Sanchez, 2007; Sackett & Laczo, 2003; Schippmann, 2010; Sliter, 2015). Among the main differential features of CM compared to JA, its lower methodological rigor in managing and controlling the variables that can impact the quality of the resulting information, the assessment of reliability, or the number of methods used for collecting information or developing descriptor content (Schippmann et al., 2000) have been pointed out. CM practices also succeed in identifying attributes that are more independent of specific job tasks and, therefore, more generic than those outlined in JA (M. A. Campion et al., 2011). Their results are therefore appropriate not only for certain jobs, but also for job families, roles, groups of occupations, organizations, economic sectors, or even the entire workforce (e.g., Kurz & Bartram, 2002; Mansfield, 1996). Despite the wide use of competency models, there is a surprising lack of literature that explicitly addresses the methodology underlying their building and development. Exceptions include some good practice guidelines for competency modeling (M. A. Campion et al., 2011), papers focused on building models for specific jobs and organizations (e.g., Lievens et al., 2004; Lucia & Lepsinger, 1999), research or consulting area studies (Mansfield, 1996; Nikolaou, 2003; Rothwell & Lindholm, 1999; L. M. Spencer & Spencer, 1993), or some national or international initiatives focused on JA or foundational skills (e.g., Mayer, 1992; National Center for O*NET Development, n.d.; OCDE, 2013). Despite this variability, most of these papers present some step-by-step directions related to how to collect data, the identification of the model’s competencies, and the presentation and description of the results, with reference to any type of empirical validation being much less frequent (Coffey, 2010; Ryan et al., 2012). Literature Review as a Source of Data for Competency Modeling The information and data collection methods typical of CM do not differ greatly from those used in JA, such as questionnaires or Q data, rating scales, interviews, or focus groups (Strah & Rupp, 2021). One of these methods is literature review: many competency modeling processes, especially those with a high degree of generality, explore the literature in search of other models in the work and organizational (W/O) area before designing their own model (e.g., Ennis, 2008; Hogan Assessment Systems, 2009). Literature review in the context of CM aims to identify previous studies on the job to be modeled, scanning information published in books, academic and professional journals, theses, dissertations, or reports, as well as in other non-academic sources and unpublished studies that may be available (Marrelli et al., 2005). When the target of the CM is a specific position within the organization, the number of studies exactly matching that position to be modeled is usually very low, which leads to using as a starting point the aforementioned general models or competency dictionaries (M. A. Campion et al., 2011; Sackett & Laczo, 2003; Soderquist et al., 2010). CM processes with a more general scope logically find a greater number of references. However, to our knowledge, none of them report on a systematic procedure or explicitly detail the key elements of the literature review conducted, such as bibliographic sources, search terms, analysis and synthesis procedures or criteria for the selection of competencies. Likewise, none of them consider as a source of data the lists of competencies used by studies in the employability area, where the aim is to identify the competencies that are valued as most important to get a job, retain it, or perform it successfully, generally at the end of higher education (van Harten et al., 2021). This type of studies usually builds a ranking of perceived importance based on direct feedback from different groups related to the professional/applied field and labor market, such as university students and graduates, new employees, employers, executives, or organizations as a whole (Baird & Parayitam, 2019; Balcar et al., 2018; Jackson, 2010; Robles, 2012). It is therefore a complementary but direct source of data on the real demands and needs of organizations. Objectives The main objective of the present study is to develop a taxonomy of competencies that summarizes the main models or lists of general evidence-based competencies from the literature, so that it can serve as a reference for CM processes, both in the research/academic field and in the professional/applied field. To achieve this main objective, the following specific objectives were established: 1) to identify studies that explicitly include models or lists of general competencies; 2) to select those whose components are conceptually close to the definition of competency developed for this study, that belong to the work and organizational (W/O) and employability areas and are supported by empirical data coming from one or more sources; 3) to summarize the competencies of the selected models in a taxonomy including the elements common to all of them; and 4) to develop an operational definition of each previously identified competency. To achieve the proposed objectives, a systematic review of the literature was performed, consisting of seven successive steps adapted from Fink (2020), until a taxonomy of general competencies was obtained (Figure 1). The characteristics of each of these steps are detailed below. Step 1: Bibliographic Databases and Web Resources Selection The search procedure focused on Psycinfo/Psycarticles and Scopus. Following the recommendation to supplement bibliographic database reviews with other types of publications from grey literature or non-academic sources (Fink, 2020; Kraus et al., 2020; Sauer & Seuring, 2023), websites searches were also carried out in order to locate reports, white papers, dissertations, books, book chapters, resources, and technical manuals published by organizations, institutions, test publishers, or agencies that included competency models. Step 2: Search Terms Selection Due to the terminological heterogeneity within the competency field, several searching terms were used. To refer to competencies, “competenc*” (including “competence”, “competency” and their plurals) was used as the main search term, but also “soft skills”, “non-technical skills” and “KSA*” (including KSA and KSAO and their plurals). In some of the searches, these terms were used along with other terms and expressions such as “key”, “general”, “generic”, “work”, “at work”, "workplace", or “professional”. In reference to models, the word “model” was used as the main search term, but also others such as “list”, "taxonomy", or “framework”. For competency modeling processes, both “modeling” and “work analysis/job analysis” were used. Finally, for studies in the area of employability, the terms “employability”, “employability skills” and “employer” were used. Step 3: Search Search in Bibliographic Databases and Practical Screen: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria A first search was initially carried out in the bibliographic databases using different combinations of terms. When a combination resulted in a number greater than 1,000 results, the search was filtered using key terms, a measure that was only necessary in the Scopus bibliographic database. To reduce the large number of results obtained in this first search, a practical screen consisting of several inclusion and exclusion criteria was applied (Fink, 2020). To apply the inclusion criteria, the filters options of the databases’ search engines were used, selecting studies: a) in English or Spanish, b) peer reviewed, c) published between 1973 and 2022, d) related to adult humans (Psycinfo/Psycarticles), e) belonging to the Social Sciences (Scopus), and f) located in European, American and Oceania countries (Scopus). Next, a content analysis of the abstracts of the selected papers was carried out and a set of exclusion criteria was applied. These criteria excluded studies: a) that did not explicitly contain models or lists of competencies, b) located in countries outside Europe, America, or Oceania (Psycinfo/Psycarticles), c) referring to educational competencies of children, schoolchildren or Higher Education students, or d) that included competency models focused on management roles or specific professional sectors (e.g., teaching, clinical psychology, construction, medicine...). Search and Selection of Papers and Documents From Non-academic Sources (Grey Literature) In addition, the terms and combinations described above were used to carry out a set of searches and queries on websites and publishing portfolios. Bearing the criteria of the practical screen in mind, as the searches were carried out in these non-academic sources, books, book chapters, tests, white papers, technical reports, and online resources that met these criteria and that had been published by any of the organizations, institutions, publishers or agencies listed in Appendix A were selected. Step 4: Full-content Analysis and Database Building The next step consisted of a full-content analysis of the studies that met the practical screen criteria in order to create a database with detailed information. The following data was extracted from each paper: source, year, location, presence/absence of a competency model, target model (new at the time of paper release or previously existing), name and bibliographic reference of the model, absence/presence of an operational definition of the model competencies, purpose of the study, area (Work/Organizational, Employability), sector (general, management, business...), and number and type of empirical evidence (survey, Q data, ratings, meta-analysis or source analysis, SME/Focus Group, interview or job advertisement analysis). This database can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon request. Step 5: Methodological Screen A methodological screen was applied to identify articles that met certain scientific and quality standards (Fink, 2020). This screen excluded from the database those studies that: a) were not based on at least one empirical evidence for the development of the model, and b) used a definition of competency that was conceptually far from the one developed for this study (competencies as learning outcomes, core competitive aspects of corporations or foundational and literacy skills, mainly). Step 6: Review and Synthesis of Results To synthesize the main components of the models included in the selected articles, competencies, and definitions of the CompeTEA model (Arribas & Pereña, 2009) were used as a framework, since it is the most used model for the assessment of competencies by Spanish practitioners (Muñiz et al., 2020). The procedure was as follows. Firstly, all the competencies from the models or lists of the papers that passed the practical and methodological screens were taken as variables. In the employability studies that presented a ranking of competencies ordered by importance, only those that occupied the first ten positions in each ranking were taken. Next, the degree of similarity between the content of each of these variables (source competencies) and any of the CompeTEA model competencies (reference competencies) was then assessed. To this end, the definitions of the competencies were used, when available or, in their absence, the name or label with which they were denominated. Step 7: Development of the Taxonomy and Operational Definitions To develop the general competencies taxonomy, two reviewers independently analyzed the content of each of the source competencies and applied the following decision rules: 1) when the source competency belonged to the same content universe as one of the reference competencies and both used the same name or label, they were considered as the same competency; 2) when the source and reference competencies shared content, but used a different name or label, they were also considered as the same competency, but the label of the source competency was added to a section attached to each reference competency called “other labels”; 3) when the content of the source competency did not have a clear correspondence with any of the reference competencies, it was provisionally added to the taxonomy and reserved as a reference competency for subsequent comparisons. At the end of the process, the agreement between both reviewers was calculated using Cohen’s kappa index and any divergences were resolved. Next, a table was created to show the frequency of appearance of each competency in the analyzed studies. To consider a competency as part of the definitive taxonomy, it had to appear in at least two of the studies (frequency ≥ 2), thus ruling out any variable with a single appearance. It was also decided to discard any competency that, at an individual level, deviated from the definition of competency adopted in the present study. The last step consisted in developing an operational definition of each competency in the taxonomy. For this purpose, the definition of the CompeTEA model was taken as a reference and, failing that, an adaptation of the one(s) used in the original studies. Search Results and Practical Screen Bibliographic database searches used 23 combinations of terms (Table 1), returning a total of 14,541 results (5,783 in Psycinfo/Psycarticles; 8,758 in Scopus). The number of results per search ranged from 8 (for the query “taxonomy of competenc*” OR “competenc* taxonomy”) to 663 (for the query “competenc* model”) in the Psycinfo/Psycarticles database (mean = 251.4, SD = 192.2) and between 21 (for the “taxonomy of competenc*” OR “competenc* taxonomy”) and 982 (for the query “Soft Skills”) in the Scopus database (mean = 398.1, SD = 283.3). Table 1 Search Terms, Search Fields, Search Results (N), and Number of Papers Meeting Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria (Practical Screen), by Bibliographic Data Source   Note. T = title; A = abstract; K = key; TH = Thesaurus. Search in Scopus restricted by the following keywords: 1“Competenc* model”; 2KSA*; 3“Key competenc*”; 4“Soft Skills” EXCLUDE Students; 5“Competence”; 6“Employability Skills”; 7Employer OR Skill OR Competenc*. Table 2 Frequency and Percentage of Excluded Papers in Each Area after Applying the Methodological Screen, by Criteria   Note. h%: horizontal percentage; v%: vertical percentage. This large number of results was drastically reduced by applying the practical screen. The inclusion criteria reduced Psycinfo/Psyarticles search results by 46.2% (n = 2,669) and Scopus search results by 38.2% (n = 3,344). The exclusion criteria were much more restrictive, selecting a total of 136 results: 2.3% of the remaining Psycinfo/Psyarticles search results (n = 61) and 2.2% of those from Scopus (n = 75). Of these 136 results, 67 were duplicate references, either because they were the same article but came from different queries within the same database (19 in Psycinfo/Psyarticles; 14 in Scopus), or because they were duplicate in both databases (34 results). The number of articles from the bibliographic databases, once duplicate references were excluded, was equal to 69. The search was then complemented with non-academic sources, adding 37 papers from grey literature (6 books or book chapters, 4 publications from test publishers, 22 technical reports and 5 online resources), which represented a total number of 106 studies from the search results. Full-content Analysis and Methodological Screen A full-content analysis was performed on the set of 106 studies that initially passed the practical screen. During this process, 36 papers were detected that, based on the analysis of their corresponding abstracts, seemed to pass the practical screen, when in fact they did not meet any of the exclusion criteria after the full-content analysis. Of these 36 papers, 23 referred to specific sectors, such as management, economics/business, medicine, construction, etc., 7 did not include any type of model or explicit list of competencies, and 6 met both of these exclusion criteria at the same time. These papers were discarded, reducing the number of studies that passed the practical screen to 70. Of these, 32 came from the W/O area (45.7%) and 38 came from the employability area (54.3%). The application of the methodological screen excluded 43 of these 70 studies (Table 2). Most of the exclusions were due to conceptual issues, particularly in the employability studies. Some of them understood competencies as learning outcomes (e.g., European Union, n.d.) or supported competencies specific to Higher Education (e.g., Michavila et al., 2016; Teijeiro et al., 2013). Others were web resources on broad national or international classification systems, such as O*NET (National Center for O*NET Development, n.d.), ISCO (International Labour Organization, n.d.), and ESCO (European Commission, n.d.), with a level of specificity and detail much closer to job analysis procedures than competency modeling ones. Finally, other papers conceptualized competencies under the Core Competencies model (Prahalad & Hamel, 1990) or focused on foundational or literacy skills, such as the SCANS project (ACT, 1995; Bates & Phelan, 2002; Secretary’s Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills, 1991), the Mayer Key Competencies framework (Mayer, 1992), the ASTD model (Carnevale et al., 1988), or the Employability Skills Framework (Curtin, 2004), which also led to their exclusion. The entries deleted for lack of empirical evidence were mainly W/O papers, theoretical studies referring to emotional competencies (e.g., Emmerling & Boyatzis, 2012; Morone et al., 2016) or book chapters and white papers on previously existing models (e.g., Bartram, 2004, 2012). Finally, 9 articles were eliminated for both reasons, that is, due to conceptual problems and lack of evidence. Descriptive Analysis of the Selected Studies Table 3 presents the descriptive data extracted from the complete content analysis of the selected studies after applying the methodological screen. Based on the publication date, the first two studies belonged to the W/O area and were published in 1993 (Robertson & Kinder, 1993; L. M. Spencer & Spencer, 1993), while the most recent article belonged to the area of employability and was dated in the year 2020 (Strong et al., 2020). The fact that all studies prior to 2010 were mostly in the W/O area stands out, while from 2010 onwards employability studies prevail. Regarding location, the majority came from Europe (55.6%). Table 3 Descriptive Data on Selected Studies After Applying the Methodological Screen, by Area   Note. h% = horizontal percentage; v% = vertical percentage. The main objective of 51.9% of the selected studies was to develop a ranking based on the feedback from different groups regarding the most important characteristics for entering the labor market, to maintain a job or succeeding in it. Most of these studies (13 out of 14) logically came from the area of employability. The rest of the studies were aimed at competency modeling (25.9%), competency assessment (14.8%), or to provide empirical support to previous work (7.4%), with the majority of them (12 of 13) being from the W/O area. Regarding the type of models or lists within each paper, 85.2% presented a new model on the date of publication, with only 4 papers focusing on previously existing models. Approximately 1 out of 3 papers did not include any definition of the competencies of their lists or models, papers that, despite this fact, were still taken into account for the subsequent phases. Empirical Evidence Used by the Selected Studies for Competency Modeling This section presents the results regarding the number and type of evidence used in the selected studies to develop their respective models. In terms of number of evidence sources, 59.3% of the models were based on a single data collection method, 33.3% on two methods, and 7.4% on three. None of the studies used more than 3 sources of evidence to give support to their model. Regarding the type of data collection method, the two most frequently used were survey and Q data (Figure 2): surveys were the most used in the employability area (with a ratio of 13/1) while Q data were the most used in the W/O studies (with a ratio of 10/1). The subject matter expert (SME) method, along with the interview, were also two types of evidence widely used and shared by both areas, while rating scales and meta-analyses or source analyses were only used in the W/O area. Here a clarification should be made regarding the method categorized as “meta-analysis or source analysis”. Although these were studies that certainly used meta-analytic techniques to obtain their model, the sample on which these techniques were based was composed of internal studies from consulting firms specialized in human resources; consequently, these are results that are more difficult to replicate and with a more limited scope than those usually derived from this approach. Synthesis of the Selected Studies Of the 27 studies selected, 23 presented models or lists of competencies that were completely new at the time of publication, with a total number of referenced variables equal to 427 (mean = 18.57, SD = 8.69). These variables were the focus of the analysis and synthesis process to obtain the taxonomy of general competencies (Table 4). Table 4 Summary of the Synthesis Process to Obtain the Taxonomy of Competencies from the Variables of the Selected Papers   Of the set of 427 initial variables, 127 were excluded for two reasons. The majority (110 out of 127; 86.6%) did not appear among the top 10 positions in the rankings of the area of employability of their respective studies. This measure ensured that the final taxonomy included only variables that had been considered important by different labor market agents (employers, students, teachers...). The remaining 17 variables (13.4%) were not included for content reasons. For example, Risk Management, Team Building, Citizenship or Assertiveness were some of the competencies cited in the studies that appeared in only one model or list of the 23 analyzed and were excluded for this reason. A small number of variables were also excluded because they referred to foundational skills (e.g., literacy, calculation, computer skills) and others that used large, non-specific labels for their naming (e.g., “job-specific competencies” or “hands-on training in discipline”). In total, 95.8% of the variables from the studies in the W/O area (158 out of 165) and only 54.2% from the employability area (142 out of 262) were included within the analysis and synthesis process, for the aforementioned reasons. Based on the definitions and/or labels of the remaining 300 variables, two independent reviewers assigned each variable to a competency of the taxonomy, a procedure that led to a high percentage of agreement (97.3%) and a kappa index of .947, indicative of an almost perfect agreement (Landis & Koch, 1977). The few discrepancies that were observed were solved by consensus. During the synthesis process, it was observed that 12 variables were involved in more than one competency of the taxonomy. For example, the “deciding & initiating action” competency of the Great Eight Competencies Model (Bartram, 2005) was assigned to the “decision making” competency of the taxonomy but also to the “initiative” competency, which meant a higher level of specificity than that adopted in the source study. Other variables that were assigned to more than one of the competencies of the taxonomy were, for example, “critical thinking/problem solving” (Baird & Parayitam, 2019), “learning ability” and “adaptation to change” (Fundación Everis, 2015) or “analyzing and solving problems” (Strong et al., 2020), among others. The opposite effect was also observed: the content of 38 competencies included a higher level of detail than that of the reference competencies, so it was decided that several of them could be included in the same competency of taxonomy. For example, “managing change” and “flexibility”, two competencies from Hogan’s model (2009), were assigned to the same “adapting to changes” competency. Other examples were the “relationship development” and “sociability” competencies of the BIP model (Hossiep & Paschen, 1998), which were included in the “building relationships” competency, or the “written communication” and “oral communication” competencies (National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2019), that were included under a more general “communication” competency. It should also be noted that there were variables that were assigned to a competency when their label or name may seem to indicate the opposite, as a consequence of the lack of terminological clarity of the competency field. Take as an example the “interpersonal sensitivity" variable, which was assigned to two competencies, “empathy” and “teamwork and cooperation”, given that in the source study it was defined as “empathic/perceptive/friendly” but also as “team skills” (Robertson & Kinder, 1993, p. 231). The result of the process led to a taxonomy consisting of 36 general competencies, 22 coinciding with those of the CompeTEA model used as a reference and 14 additional competencies. None of the studies used for the synthesis covered all the competencies of the taxonomy (Table 4, last column). Among the models in the W/O area, the Hogan model covered the highest percentage of the taxonomy’s competencies (80.6%), although it was also the one that included the largest number of source competencies (51). In addition to CompeTEA (61.1%), other models that covered at least 50% of the taxonomy’s competencies were the models of Bartram (2005), Boyatzis et al. (2000), and Spencer and Spencer (1993). None of the studies in the employability area reached a percentage higher than 40%. The General Competencies Taxonomy The taxonomy with the 36 general competencies resulting from the synthesis is presented in Table 5, along with the frequency with which each of them is cited in the 23 models analyzed. Both the operational definition of each one, as well as the set of other labels that were compiled during the synthesis process, can be consulted in Appendix B. Table 5 Competencies in the Taxonomy and Number and Percentage of the Selected Papers in Which Each One Appears, by Area   Note. Competencies that do not match the CompeTEA model are in italics. There is a set of competencies in the taxonomy, led by “teamwork and cooperation”, which appears in more than 50% of the studies analyzed. Therefore, these are competencies with a significant support in the literature reviewed. On the other extreme, some competencies were cited only twice, the cut-off point for entering the taxonomy, which represented less than 10% of the studies analyzed. When analyzing the content of the taxonomy by area, some general competences appear significantly more often in W/O studies than in the top positions of the employability rankings. This is the case of “influence”, “developing others”, “emotional self-control”, “organizational commitment”, or “information seeking”, among others. On the contrary, some competencies appear to a greater extent in the employability rankings than in the W/O models, such as “communication”, “learning and continuous improvement orientation”, or “reliability and accuracy”. The main objective of this study was to develop a taxonomy of general competencies related to the workplace. To this end, we conducted a systematic review of the main models of general competencies in the literature that were based on empirical evidence and searched for elements common to all of them. Having successfully achieved these objectives, we consider that the main contribution of this study is of a practical nature. One of the decisions to be made when developing a new competency model is to build it from scratch or use a previously existing dictionary or library of competencies as a reference (M. A. Campion et al., 2011; Sackett & Laczo, 2003; Soderquist et al., 2010). A taxonomy of competencies like the one we present here makes it easier to select the second option, explaining in that way, and with less effort, part of the job performance variance (Furnham & Mansi, 2011; Ryan et al., 2012). In this practical sense, a general competencies taxonomy can be used in at least three ways. One of the options would be to select a set of competencies from the taxonomy as the initial or base structure of the model to be developed, then adding the technical competencies or specific behaviors that the organization may consider to be important (Mansfield, 1996). A second option would involve designing the model directly from the taxonomy, selecting the competencies that are considered strategically important and adapting the language used to that of the organization, thus aligning its components with the corporate strategy (M. A. Campion et al., 2011). A third way would involve adopting a set of these general competencies as an initial list on which to base the content of other data collection methods for competency modeling, such as interviews, surveys or focus groups (Marrelli et al., 2005), or the content of a top-down analysis, where the pre-existing information about competencies is validated using primarily quantitative approaches (Parkes, 2021). Another interesting point that can be observed is that the results, both in each of the steps of the review and at the end of the process, are consistent with some theoretical issues about the concept of competency that are currently well established. Firstly, the terminological dispersion associated with the competency movement led to an unusually large number of searches in bibliographic databases, and associated results, for a systematic review focused on content analysis (Sauer & Seuring, 2023; Seuring et al., 2021). However, the need to explore this full range of terms associated with models and competencies has been confirmed, given that 80% of our searches in bibliographic databases (36 out of 45) provided one or more entries to the full-content analysis step. From a conceptual point of view, and given the lack of an agreed definition, it has been essential to construct a clear definition of professional competency that would serve as a reference. Although the definition constructed for this study is broad-spectrum and not very restrictive, the reference to individual behaviors, and especially to outstanding performance, as defining elements was enough to discard a high percentage of entries. Papers such as Baczynksa et al.’s (2016), Fahrenbach’s (2022), or Freire et al’s. (2013) include models of general competencies based on empirical evidence, but the concept on which they are supported defines competencies as learning results, as key competitive factors, or as foundational and basic skills, all of them conceptually far from the reference definition used in this review. Some of the limitations of the general models of competencies in the W/O area have been supported by the results. In our review, these types of models were not very prevalent (only 8 models since 1973), have been developed years ago (the most current one dates from 2013), and have limited empirical support: 12 out of the 20 models that passed the practical screen (60%) were exclusively theoretical papers. These results underline the need to develop general competency models that are up-to-date and evidence-based (Sackett et al., 2013). Previous publications questioning the existence of competencies common across different jobs, occupations, or organizations (e.g., Lucia & Lepsinger, 1999; Pereda & Berrocal, 2011) have not been supported by our results. Our analysis makes it clear that certain competencies are consistently repeated in models from different locations, dates, and purposes. Significant overlaps can be seen not only in terms of labels or names, but also in terms of the behaviors that define each competency and the worker attributes to which they refer. This overlap has been further supported in our study by an almost perfect agreement between two independent reviewers. This finding was expected and provides additional evidence that supports M. A. Campion et al.’s (2011) and other authors’ findings, both from the field of Work and Organizational Psychology (e.g., Op de Beeck & Hondeghem, 2009; Rothwell, 2002) and from other fields, such as education (e.g., González & Wagenaar, 2003) or employability (e.g. Young & Chapman, 2010). Consequently, the taxonomy that we present here can be considered as a first approach to a general and inclusive model of professional competencies that reflects the commonality underlying different models in the literature that are based on empirical evidence. Competencies such as Teamwork and collaboration, Adapting to changes, Communication or Customer orientation are just some of the competencies that could be candidates to be part of this general model, although their real importance remains to be established from other perspectives and using other methods. The inclusion of studies from the area of employability in the review process provides, in our opinion, an interesting contribution. Firstly, because it represents additional evidence that contradicts the idea that general competencies, as those included in the taxonomy, can be perceived by professionals as irrelevant to their needs (Bartram, 2005; Cheetham & Chivers, 1996; Markus et al., 2005; Megahed, 2018; Stasz, 1997; Woodruffe, 1992). Secondly, due to the studies of this area, it has been possible: a) to add some competencies to the taxonomy that otherwise would not have been considered, such as Problem solving, Self-direction, or Active listening, and b) to enhance other competencies valued as important for employability, but less represented in the models of the W/O area, such as Communication, Integrity and professional ethics, or Learning and continuous improvement orientation. And, in addition, because it has provided a way to obtain direct information on the demands of different important groups in the professional/applied field demand, which may help in the need to reduce the gap with the research/academic field. Finally, the present study represents an interesting contribution to the demands for greater methodological rigor associated with competency modeling (M. A. Campion, 2011; Sackett et al., 2013; Schippmann, 2000; Sliter, 2015), in two senses. First, as a procedure in itself: using a systematic literature review rather than any other type of review has a number of methodological advantages (Fink, 2020; Kunisch et al., 2023; Paul & Barari, 2022; Sauer & Seuring, 2023). Second, a general competencies taxonomy that brings together evidence from bibliographic databases and grey literature provides a starting point with sufficient methodological guarantee on which to support the development of new models, both in the professional/applied field and in the research/academic field. Limitations and Future Research Although the present study met the proposed objectives, it has some limitations. Firstly, the search and review process may have overlooked some relevant study. In the case of grey literature, due to the impossibility of carrying out a thorough search of every organization, institution, publisher, or agency engaged with the field of competencies. In the case of bibliographic databases, by focusing the practical screen on the analysis of the abstract content. It remains to be examined whether other methodologies would lead to the same taxonomy of competencies, e.g., using other systematic review methods, searching in other databases, and/or exploring specific sectoral models with the aim of extracting the elements common to all of them. Secondly, the analysis and synthesis process adopted the level of content specificity defined by the competencies of the CompeTEA model, the most frequently used for the assessment of competencies among Spanish practitioners (Muñiz et al., 2020). Perhaps using another model as a reference (e.g., the Hogan's model) or adopting another level of specificity, not only in terms of the competencies of the taxonomy but also in terms of the competency definition constructed as a reference, would possibly have led to a taxonomy with a different composition. Another potential limitation inherent to the synthesis process was undoubtedly due to the studies that did not include any definition of their competencies: making decisions regarding the composition of a competency taking the label or name as the only reference is necessarily associated with greater error, even if the inter-rater agreement was high. Thirdly, the definition developed for each competency in the taxonomy has also taken as a reference the CompeTEA model or, where unavailable, a synthesis of the definitions presented in other studies analyzed in the review process. This issue may limit the applicability of the taxonomy in competency modeling processes that require an exact adherence to definitions that are substantially different from those presented here. Likewise, the content of some of the competencies in the taxonomy seems clearly related to management positions, such as Leadership, People management, or Strategic approach, while others, such as Teamwork and collaboration or Customer orientation, could in principle be applicable to a greater number of occupational groups. Although the management competency models were intentionally excluded from the search due to their specificity, it was unavoidable that, within the general models included in the review, there would appear competencies that also include part of the behavior of managerial positions, with a long tradition in the competency field. Similarly, there are competencies that are more focused on processes or on the “KSA” component (e.g., Negotiation or Problem Solving) than on the personal attributes of the “O” component of the competencies (e.g., Resilience or Achievement Orientation). Both the generality of the competencies included in the taxonomy that appear more linked to managerial positions and the importance of those competencies that are more process-oriented than attribute-oriented, or vice versa, are questions that remain open and on which data should be collected to provide more information. Finally, the frequency of appearance of the of the competencies in the taxonomy could be interpreted as an indicator of their importance for job performance. However, it is important to note that perceived importance is one of the main parameters for developing a competency model and that the taxonomy presented here is not intended to be a model as such, but a resource for competency modeling. The real importance of the competencies in the taxonomy and their empirical cross-occupational relevance remains to be determined using direct data collection methods typical of competency modeling (Q data, surveys, focus groups...). The data from these methods will also provide information on which positions are more related to which competencies of the taxonomy, the weight that each of them has in explaining the job performance in each occupation or group of occupations, or their predictive capacity in the field of employability. Only in that case will it be possible to complement the information in this study and a general model of professional competencies based on empirical evidence can be developed. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Arribas-Aguila, D., Castaño, G., & Martínez-Arias, R. (2024). A systematic review of evidence-based general competency models: Development of a general competencies taxonomy. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 40(2), 61-76. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2024a6 References Appendix A Organizations, Institutions, Publishers, and Agencies that Provided the Non-academic Sources Pre-selected for the Taxonomy Organizations, Institutions, Publishers, and Agencies that Provided the Non-academic Sources Pre-selected for the Taxonomy>   Definition and Other Names of the General Competencies of the Taxonomy |

Cite this article as: Arribas-Aguila, D., Castaño, G., & Martínez-Arias, R. (2024). A Systematic Review of Evidence-based General Competency Models: Development of a General Competencies Taxonomy. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 40(2), 61 - 76. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2024a6

Correspondence: david.arribas@hogrefe-tea.com (D. Arribas-Aguila).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS