Can Activity Worthwhileness Explain OCB-I Change? The Mediating Role of Positive Emotions

[ÂżPuede la valĂa de la actividad explicar el cambio de OCB-I? El papel mediador de las emociones positivas]

Aleksandra Muric1, Aida Soriano1, Salvatore Zappala2, José M. Peiró1, and 3

1Instituto de InvestigaciĂłn en PsicologĂa de los Recursos Humanos, del Desarrollo Organizacional y de la Calidad de Vida Laboral (IDOCAL), Spain; 2UniversitĂ di Bologna, Italy; 3Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones EconĂłmicas (IVIE), Valencia, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2022a8

Received 21 February 2021, Accepted 12 May 2022

Abstract

The competitiveness of today’s markets requires employees to do more than is formally expected from them by collaborating with others to benefit the organization (e.g., organizational citizenship behavior focused on individuals, OCB-I). Based on the idea that eudaimonic wellbeing positively influences OCB-I, and considering that positive emotions lead to optimal functioning and important work outcomes, this study analyzes the mediating role of positive emotions in the relationship between activity worthwhileness and OCB-I. Results of hierarchical regressions in a two-wave longitudinal study with a sample of 108 white collar employees show that activity worthwhileness indirectly (but not directly) explains change in OCB-I through positive emotions. Therefore, when it comes to improving performance in the workplace, investment in both hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing contributes to more effectively benefitting both employees and organizations.

Resumen

La competitividad de los mercados actuales requiere que los empleados hagan más de lo que formalmente se espera de ellos colaborando con otros para favorecer a la organización (por ejemplo, comportamiento de ciudadanía organizacional centrado en las personas, OCB-I). Partiendo de la idea de que el bienestar eudaimónico influye positivamente en el OCB-I, y considerando que las emociones positivas conducen a un funcionamiento óptimo y a importantes resultados laborales, el presente estudio analiza el papel mediador de las emociones positivas en la relación entre la valía de la actividad y el OCB-I. Los resultados de regresiones jerárquicas en el presente estudio longitudinal con una muestra de 108 trabajadores administrativos muestran que la valía de la actividad explica indirecta, pero no directamente, el cambio en OCB-I a través de las emociones positivas. Por lo tanto, cuando se trata de mejorar el desempeño en el lugar de trabajo, la inversión en bienestar, tanto hedónico como eudaimónico, contribuye a favorecer tanto a los empleados como a las organizaciones.

Palabras clave

Comportamiento de ciudadanĂa organizacional, OCB-I, ValĂa de la actividad, Emociones positivas, Bienestar, TeorĂa de ampliaciĂłn y desarrolloKeywords

Organizational citizenship behavior, OCB-I, Activity worthwhileness, Positive emotions, Wellbeing, Broaden-and-build theoryCite this article as: Muric, A., Soriano, A., Zappala, S., & Peiró, J. M. (2022). Can Activity Worthwhileness Explain OCB-I Change? The Mediating Role of Positive Emotions. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 38(2), 93 - 100. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2022a8

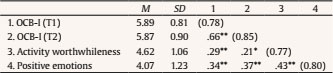

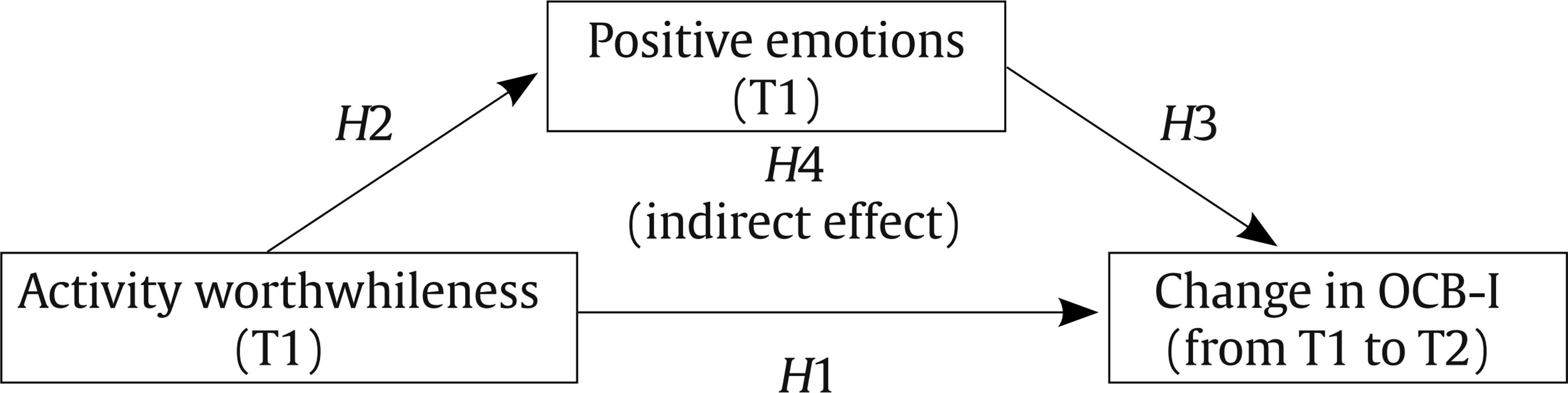

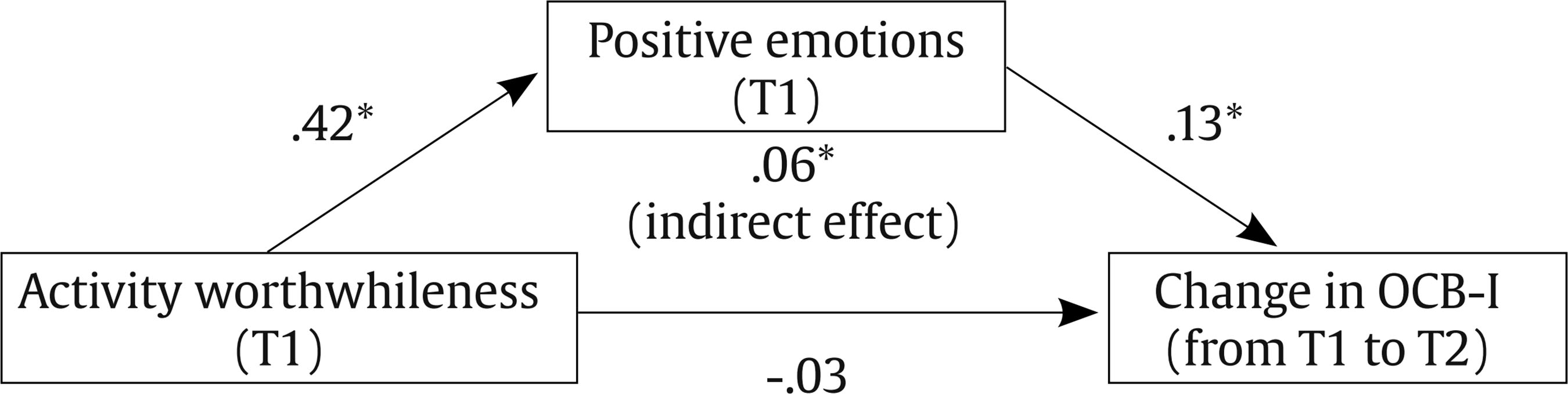

Jose.M.Peiro@uv.es Correspondence: Jose.M.Peiro@uv.es (JosĂ© M. PeirĂł).For many years, research has focused on studying performance as one of the most important organizational outcomes (Motowidlo & Kell, 2012). Today, the market seems to be more competitive than it was decades ago; thus, companies are looking for any added value that they can get from employees, in addition to the fulfillment of formal requirements and prescribed job tasks. In this regard, organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), understood as “individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization” (Kozusznik et al., 2019; Organ, 1988, p. 4), is a relevant research issue. OCB provides organizations with significant advantages because it contributes to the maintenance and enhancement of the socio-psychological context of the workplace, which increases organizational effectiveness through workers’ behavior (Ocampo et al., 2018; Organ, 1988). OCB has been present in research for more than a decade, but the majority of the knowledge about OCB still comes from cross-sectional data, and so there is a need for longitudinal and time lagged studies (Ocampo et al., 2018). This is not surprising if we take into consideration that OCB was considered stable. However, scholars have recently acknowledged that OCB can be understood as a dynamic and time-dependent psychological phenomenon (Lavy, 2019; Methot et al., 2017). Additionally, although it is true that OCB always promotes the effective functioning of the organization (Ocampo et al., 2018; Organ, 1988), it is worth noting that these behaviors may be directed at the organization (i.e., OCB-O; e.g., staying extra hours to finish or improve a report or “going the extra mile” for quality) or at individuals in the organization (i.e., OCB-I.; e.g., helping a new employee to find his or her way around) (Chiaburu et al., 2018; Organ & Konovsky, 1989; Williams & Anderson, 1991). Because today’s workplace is more team oriented and work roles are designed in such a way that employees often depend on each other, OCB-I is currently the most recognized OCB construct (Bambale et al., 2015; Ocampo et al., 2018). Therefore, keeping in mind these characteristics of the workplace and the potential time dynamic of the construct, the present study aims to explain the change in OCB-I that can occur over time. The happy-productive worker model states that happy employees usually perform better than unhappy workers (Wright & Cropanzano, 2007). In the past, organizational research equated the term happiness with hedonic wellbeing, claiming that employees’ satisfaction with their own work is what makes them do their best. However, the pleasure-purpose principle postulates that happiness consists of moments when either pleasure or purpose is felt, and the amount of happiness in one’s life depends on the actual balance between them (i.e., eudaimonic wellbeing, Dolan, 2014). Therefore, when researching OCB-I, it is important to consider both dimensions of wellbeing: hedonic (with the focus on experiencing positive emotions) and eudaimonic (highlighting the importance of finding purpose and meaning, such as having the feeling of carrying out worthwhile activities) (Sonnentag, 2015). Regardless of the existing distinction, eudaimonic wellbeing, as an antecedent of OCB-I, has been far less present in the literature, and researchers have focused more on the hedonic dimension (Kozusznik et al., 2019; Sonnentag, 2015; Soriano et al., 2020). Furthermore, studies that included eudaimonic dimensions usually portrayed it through more global constructs (e.g., meaningful work), whereas focal constructs such as activity worthwhileness, which aims to specifically capture the meaning and purpose employees experience in their daily work activities (Kozusznik et al., 2019), are still not present in the literature. Finally, the Broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 2001) postulates that positive emotions broaden an individual’s thought-action repertoire and promote discovery of novel and creative actions, ideas, and social bonds, making an individual more likely to engage in new activities, usually with social or helping components. In the case of OCB, there are two lines of thought. On the one hand, the meta-analyses by Dalal (2005) and Lyubomirsky et al. (2005) support positive affect as an antecedent of OCB. On the other hand, first, Lavy (2019) states that, when feeling happy and good, teachers tend to engage less in OCBs on the following day; second, Miner and Glomb (2010) showed that there is no relationship between OCB and positive mood. In order to solve this disagreement, some scholars have understood the importance of examining this relationship by taking into account different dimensions of OCB rather than just general measures. Results of these studies show that positive affect (Dávila & Finkelstein, 2013; Lee & Allen, 2002; Wagner, 2017; Williams & Anderson, 1991) and positive emotions (Ma et al., 2016) have relationships with OCB-I specifically. Therefore, considering that the hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions of wellbeing are distinct but interrelated (Fredrickson, 2016), the present study aims to contribute to the literature by providing a more comprehensive view of workers’ (hedonic and eudaimonic) wellbeing and analyzing its effect on OCB-I over time. More specifically, we intend to clarify the mediating role of positive emotions in the relationship between activity worthwhileness and OCB-I. Therefore, from a theoretical perspective, this research contributes to improving the understanding of the way OCB-I is influenced by employees’ wellbeing by unraveling its dimensions and testing the mechanisms that may explain the interrelationship between hedonia and eudaimonia. From a practical point of view, the results of the present study highlight the importance of considering and improving both dimensions of worker wellbeing through HR practices in order to achieve the added value that organizations need to survive in the current competitive world (i.e., OCB-I). In this way, both companies and employees will obtain benefits from these practices. Organizational Citizenship Behavior Many organizational practices are based on performance as a key component (e.g., Khan et al., 2011; Motowidlo & Kell, 2012; Salgado, 2017). Performance is defined as “scalable actions, behaviors, and outcomes that employees engage in or bring about that are linked with and contribute to organizational goals” (Viswesvaran & Ones, 2000, p. 216). However, performance is not a uniform construct, and there have been many discussions among scholars about how to differentiate the types of performance (Harari et al., 2016; Motowidlo & Kell, 2012; Salgado et al., 2013). Viswesvaran and Ones (2000) distinguished between task performance (accomplishing duties within a formal role), counterproductive performance (behaviors that have negative value for the organization), and OCB. The definition of OCB points out three important components of this construct: it is voluntary behavior, it is not formally rewarded by the organization, and it is beneficial (Organ, 1988; Whitman et al., 2010). These three characteristics make OCB interesting to practitioners (and, therefore, researchers) because they represent “things they would like their subordinates to do but that they could not require subordinates to do by force, offers of rewards, or threats of punishment” (Motowidlo & Kell, 2012, p.106). Additionally, Williams and Anderson (1991) distinguished two independent dimensions of OCB, implying that these acts should differ depending on their target: OCB oriented towards the organization (OCB-O) and OCB oriented towards individuals (OCB-I). Ocampo et al. (2018), in their historical review of OCB, suggested that work tasks today require a lot of cooperation and collaboration both within and among teams, implying that the importance of OCB lies in the assistance we provide to our coworkers. This means that individuals are more dependent on each other at work, and so mutual support may be equally as important or even more important than support for the organization itself. Thus, the importance of researching OCB-I lies in interpersonal responsiveness, which is anchored in many management practices (e.g., self-directed work teams, decentralized decision making, etc.) (Settoon & Mossholder, 2002). Activity Worthwhileness The eudaimonic perspective on wellbeing has its roots in ancient Greece, where it was first described by Aristotle, who defined it as “living well” with the “realization of one’s potential” (Haybron, 2016). In organizational research, meaningful work has been a dominant eudaimonic operationalization, defined as the global judgement that one’s work is achieving significant, valuable, or worthwhile goals that are congruent with one’s existential values (Allan et al., 2019). However, this construct refers to work in general, and less research has examined eudaimonia by focusing specifically on work activities. Concrete experiences of eudaimonic wellbeing, such as carrying out meaningful activities at work (i.e., activity worthwhileness), are the basic components of eudaimonic wellbeing at work (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD, 2013]) because they are essential in weaving purposeful meaning in the long term (Huta & Waterman, 2013). In this regard, activity worthwhileness is understood as an “employee’s conviction that the activities carried out at work are worthwhile and useful to other people, have greater meaning, and serve a higher purpose” (Kozusznik et al., 2019, p. 5), and it has been recommended as an essential measure of eudaimonic wellbeing at work (Dolan et al., 2011) that complements activities that employees find “pleasurable” (i.e., hedonic wellbeing) (White & Dolan, 2009). Literature has analyzed the role played by different indicators of wellbeing in the organizational context (e.g., purpose in life, flow, personal growth). However, little is known about the role of eudaimonic aspects of work activities in organizational outcomes. With this information, human resource managers may realize how important it is to design worthwhile activities for their employees, so that they can feel how much they contribute to the society through their work. The Relationship Between Activity Worthwhileness and OCB-I Generally speaking, the literature has shown that different indicators of eudaimonic wellbeing contribute to increased OCB. For instance, studies have shown that people high in eudaimonia have a stronger tendency to engage in prosocial activities in general (Ryan & Deci, 2001), which is a similar construct that partially overlaps with OCB. In the same vein, individuals who see purpose in their life or feel like growing and developing engage more often in altruistic OCB in their workplace (Rastogi & Garg, 2011). Additionally, scholars found that employees who experience their job as “going beyond the self” and derive a sense of purpose and meaning from it are also more likely to exhibit OCB (Xie et al., 2017). Additionally, in a longitudinal study, Turban and Yan (2016) showed that if employees experience purpose, growth, and a feeling of contributing to society, they tend to have higher scores on OCB measured two weeks later. More specifically, focusing on the eudaimonic aspects of work activities (i.e., activity worthwhileness), a recent meta-analytic study on meaningful work showed that employees’ perception that the work they do is significant, valuable, and worthwhile is a predictor of their extra role behaviors or OCB (Allan et al., 2019). In the same vein, Kozusznik et al. (2019) showed that activity worthwhileness measured in the afternoon is positively related to changes in extra role performance measured the next morning. All this evidence aligns with the self-determination theory (SDT) perspective on eudaimonia (Ryan et al., 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2000), which suggests that when employees consider that the work activities they usually carry out are full of meaning and useful to achieve worthwhile goals, they will show enhanced performance. Thus, taking all these ideas into account, and given that no studies have been found that analyze the effects of an eudaimonic work activity (i.e., activity worthwhileness) on OCB-I over time, we propose the following hypothesis: Hypothesis 1: Employees’ activity worthwhileness at T1 will be positively related to the change in OCB-I from T1 to T2. Positive Emotions Hedonism is one the oldest philosophical doctrines and still studied today (Heathwood, 2014). From this perspective, wellbeing is understood in terms of the presence of pleasure and the absence of pain (Angner, 2010), and so it consists of the balance between pleasant and unpleasant experiences (Eid & Larsen, 2008). In the organizational context, hedonic wellbeing is defined in terms of what people think or feel about specific work factors (Robertson et al., 2011). Thus, hedonic wellbeing has also been conceptualized as the experience of positive affect (e.g., Diener, 2000). One of the forms of affect considered in research is the transient or “state” affect, which may include positive emotions (e.g., Kaplan et al., 2009). In fact, wellbeing (Warr, 2007) that considers the experience of pleasure (e.g., positive state emotions) while carrying out different work activities (Dolan et al., 2011; White & Dolan, 2009) is generally believed to represent the core of hedonic wellbeing at work (Diener et al., 2009). Evidence shows that the hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions of wellbeing are distinct but correlated, and they often have a certain synergic relationship (Joshanloo, 2016; Turban & Yan, 2016; Waterman et al., 2008). As Fredrickson (2016) points out, the interrelationship between hedonia (i.e., positive emotions) and eudaimonia (i.e., activity worthwhileness) is “an empirical, not a philosophical question”, which means that research has to discover the relationship between these two concepts. In this line, evidence has shown that some activities may trigger stronger feelings of pleasure or reward than others (White & Dolan, 2009), but a more common case is that activities pursued for their eudaimonic enjoyment are also followed by a pleasant state (Waterman et al., 2008). In this regard, studies have found that people who experience their life as purposeful and meaningful are also more prone to experiencing positive affect (Hadden & Smith, 2019; Hill et al., 2016; Zika & Chamberlain, 1992). Similar results are found in the work context. The degree to which employees perceive their work as meaningful, purposeful, or contributing to a greater social good is a good predictor of how often they feel joy or cheerfulness (Arnold et al., 2007; Ménard & Brunet, 2011). Although hedonic and eudaimonic facets of wellbeing capture distinct constructs, they are interrelated, and one can influence the other (Fredrickson, 2016). The present research, thus, aims to answer recent calls to consider the influence of eudaimonia (i.e., activity worthwhileness) on hedonia (i.e., positive emotions). In doing so, this study will provide an opportunity to build wellbeing theory. Therefore, taking all this into account, we propose the hypothesis: Hypothesis 2: Employees’ activity worthwhileness at T1 will be positively related to positive emotions at T1. Mediating Role of Positive Emotions The Broaden-and-build theory is built on the premise that positive emotions produce optimal functioning, not only in the present moment, but also over a longer period of time (Fredrickson, 2001). According to Fredrickson (2001), positive emotions broaden our thought-action repertoires. Furthermore, she suggests that, while experiencing positive states, we are more prone to pursuing a wider range of thoughts and actions than usual (e.g., play, explore, savor, and integrate). The theory assumes that the adaptive role of positive emotions stems from the fact that a broadened mindset allows individuals to engage in activities that will help them build a variety of personal resources (physical, social, intellectual, and psychological resources). Hence, it can be assumed that people who experience positive emotions at work will have a broader array of behavioral repertoires, which will make them more likely to engage in activities such as helping coworkers (i.e., OCB-I) with demanding tasks, due to their openness to new experiences and explorations. In line with the broaden-and-build theory, empirical studies show that employees who experience positive emotions get better performance evaluations from their supervisors (Cropanzano & Wright, 1999; Hosie et al., 2012), and that managers who experience positive emotions also lead better performing teams (George, 1995). Additionally, evidence also shows that positive emotions are related to behaviors that involve going above and beyond to reach organizational goals. For example, Dalal’s (2005) meta-analysis supports positive affect as an antecedent of OCB. A well-known meta-study by Lyubomirsky et al. (2005) uses cross-sectional data to show that employees who experience positive affect at work are more prone to organizational spontaneity and OCB. Nevertheless, there are also studies that show a negative (Lavy, 2019) or non-significant (Miner & Glomb, 2010) relationship between positive emotions and OCB. In order to clarify this issue, some scholars have understood the importance of examining this relationship by taking into account different dimensions of OCB rather than just general measures. Results of such studies show that positive affect has a relationship with OCB-I specifically (Dávila & Finkelstein, 2013; Lee & Allen, 2002; Wagner, 2017; Williams & Anderson, 1991). In the same vein, a sample of US and Chinese employees participated in a study on positive emotions and OCB-I (Ma et al., 2016), and both samples showed that positive emotions are significantly related to OCB-I. Therefore, based on the Broaden-and-build theory and findings from previous research, we propose the following hypotheses: Hypothesis 3: Employees’ positive emotions at T1 will positively predict change in OCB-I from T1 to T2. Hypothesis 4: Employees’ positive emotions at T1 will mediate the relationship between activity worthwhileness and change in OCB-I from T1 to T2. The main goal of this study is to test the effect of activity worthwhileness on OCB-I over time and analyze the role of positive emotions as the mediational path through which activity worthwhileness may be influencing changes in OCB-I. In doing so, the present research fills three theoretical gaps. The first gap is the limited consideration of eudaimonic indicators of wellbeing in research and their relationship with performance indicators such as OCB-I. The second gap involves the inclusion of both the hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions of wellbeing in the same model, in order to more deeply understand their interrelationship and the effect of wellbeing on OCB-I. The third gap is the lack of longitudinal studies on OCB-I. The hypothesized model is presented in Figure 1. Sample and Procedure Initially, 157 white collar employees filled out an online survey distributed on tablet devices provided by the researchers. However, some employees were not able to participate in both waves, and data from these participants were removed. Thus, the final sample consisted of 108 employees. All the companies that participated in the study are located in the Valencian Community (Spain), and their business areas include a variety of industries (e.g., banking, engineering, production sector). The process of selecting the participants in the organizations was not random. Specifically, we wanted to ensure that we included employees working in an office setting (white collar workers). Therefore, even though the companies belong to different type of industries, office work involves, to a large extent, the same functions in all of them (e.g., bookkeeping, administration, purchase management). Analysis of demographics shows that around 64% of the sample were women, and the age range of the participants was from 23 to 61 years (M = 39.45, SD = 7.42). Fifty-three percent of the participants had a university degree (Bachelor and/or Master or equivalent), around 29% had an undergraduate degree, 15% had a high school diploma, and less than 3% had a PhD. Most of the sample (around 90%) consisted of technical or administrative staff, and around 80% of the total sample had a permanent working contract. ANOVAS and t-tests were carried out in order to analyze the role that these demographic variables (i.e., gender, university degree, and type of work contract) may have on the variables of interest, and none of them showed a significant influence on activity worthwhileness (t = -1.102, p > .05; t = 0.408, p > .05; and F = 0.532, p > .05, respectively), positive emotions (t = 1.750, p > .05; t = -0.510, p > .05; and F = 0.913, p > .05, respectively) or OCB-I (t = 1.518, p > .05; t = -0.707, p > .05; and F = 2.137, p > .05, respectively). Data were gathered during company working hours on two different occasions six months apart. Participants were asked to answer spontaneously and sincerely. They were informed that the data would be treated in an aggregated manner with full confidentiality. All the employees signed an agreement form to participate and were informed that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any point. Measures Participants filled out questionnaires that measured activity worthwhileness, positive emotions, and OCB-I. Because the model predicts “change” in OCB-I, this variable was measured on both occasions, whereas activity worthwhileness and positive emotions were measured only in the first wave. Organizational Citizenship Behavior Oriented towards Individuals This variable was assessed using the Settoon and Mossholder (2002) scale. Participants were asked to indicate their degree of agreement with the statements (sample item: “I take time to listen to the problems and concerns of co-workers”. A Likert scale with a response range from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much) was used. Cronbach’s alpha for T1 was .77, whereas at T2 it was .85. Activity Worthwhileness This scale was taken from the White and Dolan’s (2009) study. The participants were asked to indicate whether they felt the activities they normally carry out at work are “…worthwhile and meaningful” (sample item). A Likert scale with a response range from 1 to 7 was used, where one 1 referred to “not at all” and 7 referred to “very much”, regarding their level of agreement with the statement. Cronbach’s alpha for the activity worthwhileness scale was .78. Positive Emotions These emotions were measured with a three-item scale (White & Dolan, 2009). The participants were asked to evaluate how often they experience certain feelings at work (sample item: “Happy”). They were told to think of a normal day at work and choose their answers based on that idea. The responses were given on a Likert scale that ranged from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). Cronbach’s alpha for positive emotions in this study was .80. All three scales have Cronbach’s alpha values larger than .70, which means they have adequate levels of reliability for further analysis. Analysis The present research aims to understand change in OCB-I. In this regard, the literature recognizes three different main ways to statistically analyze change over time (Dalecki & Willits, 1991). The first method proposes calculating the difference between the times (subtracting T1 from T2) while using T1 as a control variable. The second option suggests calculating the residuals from regressing T1 on T2. Finally, the third way proposes calculating the change by using T2 as a dependent variable while using the baseline predictor (T1) as a control variable. Accordingly, the most accurate and adequate way to calculate the longitudinal change in social sciences is by following the steps suggested in the third option (Cohen et al., 2013) because residual and difference scores do not consider the reliability of the measurement and tend to overcorrect the post-score by the pre-score. Thus, in this paper, the change score refers to the OCB-I (T2) score, controlling for the OCB-I (T1) score. All the analyses in this paper were performed using IBM’s SPSS v.24. To test the mediation models, the Process v.3.2 macro of SPSS by Hayes (2018) was used (Model 4). Table 1 shows descriptive statistics, Pearson’s correlations, and Cronbach’s alpha reliability. Before analyzing the hypothesized model, several assumptions for carrying out the mediation model were tested by running hierarchical regressions in SPSS. The first block in the hierarchical regression consisted of activity worthwhileness (T1) as a predictor and OCB-I (T1) as a control variable, whereas positive emotions were added in the second block. One of the requirements for running mediation models is that the variables cannot be highly intercorrelated because multicollinearity can lead to problems in the analysis (e.g., high standard errors, wider confidence intervals). Our data were tested for non-collinearity, and the results showed that the VIF for all variables was below 10, whereas tolerance was between .10 and 1.00, activity worthwhileness (T1): tolerance = .80, VIF = 1.26; OCB-I (T1): tolerance = .86, VIF = 1.67; positive emotions (T1): tolerance = .77, VIF = 1.31, which means that the variables in our model met the expected standards for non-collinearity. Furthermore, we tested the assumption that errors between variables were independent using the Durbin Watson measure, which should be higher than 1.5 and lower than 2.5. In the case of our model, a value equal to 2.07 was obtained, which means that the errors were independent. A histogram of standardized residuals showed that the data had normally distributed errors. Similarly, the P-P plot of standardized residuals showed points not right on the line but very close to it. Furthermore, a scatter plot of standardized residuals indicated that the data had adequate levels of homogeneity of variance and linearity. Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, Pearson Correlations, and Coefficient Alpha Reliabilities   Note. Values in parentheses are Cronbach’s alpha values. *p < .05, **p < .01. Considering the moderate significant correlation between the two dimensions of wellbeing (i.e., activity worthwhileness and positive emotions) found in our preliminary results (r = .43, p < .05), we carried out a Harman’s test (Podsakoff et al., 2003) to empirically demonstrate the distinctiveness between them. Thus, two confirmatory factor analyses were computed: a single-factor model and a two-factor model. Results support the distinctiveness of eudaimonic and hedonic wellbeing (i.e., activity worthwhileness and positive emotions, respectively), given that the two-factor model fits the data better (RMSEA = .000, CFI = 1.000, TLI = 1.025, SRMR = .030) than the alternative one-factor model (RMSEA = .225, CFI = .761, TLI = .602, SRMR = .096). Results from the mediation model show that the overall model explains 45% of the variance in change in OCB-I, F(3) = 28.77, p < .01 (Figure 2; Table 2). Activity worthwhileness does not have a direct effect on change in OCB-I between T1 and T2 (β = -.03, IC = 95% [-.17, .11]); therefore, our first hypothesis was not confirmed. Our results indicate that activity worthwhileness predicts positive emotions, β = .42, t(105) = 0.10, p < .00, and, furthermore, positive emotions predict change in OCB-I from T1 to T2, β = .13, t(104) = 0.61, p < .05, confirming Hypotheses 2 and 3. As Table 2 shows, a bias-corrected bootstrap of 5,000 resamples revealed that the indirect effect of activity worthwhileness on change in OCB-I through positive emotions was .06 (IC = 95% [.01, .12]). Because zero is not contained in the 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect, Hypothesis 4 was confirmed. Table 2 Unstandardized Effect Sizes, Standard Errors, and 95% Confidence Interval Values   Note. Results are based on 5000 bias-corrected bootstrap samples. The aim of this study was to test whether activity worthwhileness was able to predict the change in the level of OCB-I expressed within a time window of six months. Moreover, we tested whether this relationship was mediated by positive emotions. Results show that change in the level of OCB-I is significantly explained by activity worthwhileness only when mediated by positive emotions. On the one hand, results of the present research support existing literature regarding the relationship between activity worthwhileness and positive emotions, and between positive emotions and OCB-I. First, the present research suggests that someone who experiences activity worthwhileness at work will be more prone to experiencing positive emotions as well. This outcome agrees with existing evidence showing that eudaimonic states are followed by pleasant ones (Waterman et al., 2008), and that purposeful work can predict joy or cheerfulness (Arnold et al., 2007; Ménard & Brunet, 2011). Second, the claim that positive emotions positively influence OCB-I (Dávila & Finkelstein, 2013; Lee & Allen, 2002; Ma et al., 2016; Wagner, 2017; Williams & Anderson, 1991) was also confirmed because the present study shows that positive emotions predict change in OCB-I. On the other hand, the literature proposes that eudaimonic wellbeing contributes to directly increasing OCB. First, from a theoretical point of view, SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Ryan et al., 2008) claims that workers who think their work activities are full of meaning and useful for achieving worthwhile goals will show enhanced performance. Second, empirical evidence shows that people with high levels of eudaimonic wellbeing easily engage in prosocial activities in general (Ryan & Deci, 2001) and in altruistic OCB in their workplace (Allan et al., 2019; Rastogi & Garg, 2011; Turban & Yan, 2016; Xie et al., 2017). However, our results do not support this direct relationship between eudaimonic wellbeing (i.e., activity worthwhileness) and performance (i.e., OCB-I). There could be several explanations for this finding. First, no studies have been found that analyzed the effect of an eudaimonic work activity (i.e., activity worthwhileness) on OCB-I over time. Thus, although we are talking about the same general constructs as in previous literature, it is possible that when examining eudaimonia by focusing more on specific work activities and OCB specifically oriented towards helping individuals (OCB-I), the relationship may be different. Second, we also tested a mechanism through which activity worthwhileness may influence change in OCB-I (i.e., through positive emotions), and the results support the idea that there is an indirect path from activity worthwhileness to OCB-I through the mediator role of positive emotions. Therefore, aligned with the Broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 2001), which states that positive emotions expand our array of actions and provide us with energy to invest in social relationships that will, in turn, build our capacities and resources, it can be said that positive emotions fully mediate the relationship between activity worthwhileness and OCB-I. These results also highlight that the two dimensions of wellbeing behave differently in terms of the change in OCB-I, given that hedonic wellbeing (i.e., positive emotions) has direct effects on OCB-I, but eudaimonic wellbeing (i.e., activity worthwhileness) does not. This does not negate the importance of activity worthwhileness. However, it shows that hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing are different but mutually connected and interrelated in producing important extra-role behaviors in organizations. The results obtained make several theoretical contributions. First, the majority of the studies focused on OCB-I are carried out with cross-sectional data, which allows researchers to draw conclusions about relationships between the constructs, but it does not allow them to draw conclusions about their causality (Ocampo et al., 2018). Accordingly, one of the biggest contributions of this study is its lagged design because it brings us one step closer to claiming that wellbeing is a chronological antecedent of OCB-I. Second, the present research offers a comprehensive view of wellbeing as an antecedent of OCB-I over time, by considering both eudaimonic and hedonic dimensions. On the one hand, taking into account that OCB research has not paid enough attention to eudaimonic wellbeing (Turban & Yan, 2016), we contribute to highlighting its importance. On the other hand, including both dimensions of wellbeing in our study allows us to more deeply understand the mechanism that underlies their interrelationship when influencing OCB-I. Furthermore, the concept of activity worthwhileness itself is quite new in the literature and, therefore, less researched. Its nature allows us to unveil how more specific and basic experiences of eudaimonic wellbeing at work, such as performing worthwhile activities (OECD, 2013), can impact work behavior. The present study also has some limitations that should be highlighted to guide this line of research in future studies. First, it uses the same type of source for its data (self-reported measures), and so there is a risk of common method bias. Variables such as activity worthwhileness and positive emotions cannot be reported in any other way because they are individual perceptions; however, OCB-I is a construct that can also be rated by peers or supervisors. Taking this into consideration, future studies should avoid this limitation by combining these self-reported measures with supervisory ratings in order to capture a more objective picture of OCB-I at work. Second, future researchers analyzing the effect of wellbeing on OCB-I should also include additional time waves. Although our two-wave study allows us to talk about the causal effect of wellbeing on OCB-I, including more time points would contribute to a more stable confirmation of this relationship and help to explore the dynamics of change in the variables considered (Methot et al., 2017). Finally, in this study we only used one indicator for each wellbeing dimension. In order to provide a more comprehensive picture of these constructs, as well as their interrelationship and influence on OCB-I, future studies should include more indicators of both hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing. The results of the study have managerial implications. Nowadays, when choosing practices to improve employees’ wellbeing, organizations often seem to consider positive physical conditions and other perks mainly oriented towards improving workers’ hedonic wellbeing. Although these benefits probably bring joy and pleasure to their employees, results of the present study imply that organizations need to reconsider their understanding of happiness and focus on the eudaimonic aspirations of their employees. In a more concrete way, the present research suggests that if workers perceive that the tasks they perform at work are valuable and significant (eudaimonic wellbeing), this will directly contribute to improving their hedonic wellbeing (i.e., positive emotions), which will produce positive changes in their organizational citizenship behaviors (i.e., OCB-I). Therefore, eudaimonic wellbeing can be improved through various HR practices, and activity-oriented eudaimonic indicators (such as activity worthwhileness) may offer a new field that is easier to manage than more general eudaimonic indicators such as purpose in life/at work or personal growth. The results of this study show that activity worthwhileness can influence change in OCB-I over time through the mediating role of positive emotions. These results are valuable because they give a time-lagged perspective of OCB-I, which is rare in the literature. Furthermore, we obtained results that show the importance of both dimensions of wellbeing. Therefore, in a practical sense, when it comes to improving performance in the workplace, the eudaimonic dimension should be taken into consideration along with the hedonic one. Research should continue to examine the role of other eudaimonic dimensions in explaining OCB-I, especially using time-lagged designs with at least three waves. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest Cite this article as: Muric, A., Soriano, A., Zappala, S., & Peiró, J. M. (2022). Can activity worthwhileness explain OCB-I change? The mediating role of positive emotions. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 38(2), 93-100. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2022a8 References |

Cite this article as: Muric, A., Soriano, A., Zappala, S., & Peiró, J. M. (2022). Can Activity Worthwhileness Explain OCB-I Change? The Mediating Role of Positive Emotions. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 38(2), 93 - 100. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2022a8

Jose.M.Peiro@uv.es Correspondence: Jose.M.Peiro@uv.es (JosĂ© M. PeirĂł).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS