Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand WorkersŌĆÖ Production of Safe Food

[Aplicando la teor├Ła de la conducta planificada para entender la producci├│n de alimentos seguros por los trabajadores]

Gary S. Nickell1 and Verlin B. Hinsz2

1Minnesota State University Moorhead, U.S.A.; 2North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND, U.S.A.

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2023a10

Received 24 October 2022, Accepted 21 June 2023

Abstract

Recent outbreaks of food related illness have brought greater attention to protecting food from contamination. Psychological approaches to behaviors during food processing can contribute to workers’ efforts to keep food safe and avoiding contamination. This study examines the effectiveness of the theory of planned behavior (TPB) in predicting self-reported food safety behaviors of turkey-processing workers. Consistent with the TPB, this study suggests that attitude toward the behavior, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and behavior intention play important roles in understanding how to prevent foodborne contamination. Results also show that background factors, specifically gender, may be important in applying the TPB in specific work settings. Accordingly, salient beliefs that workers hold about food safety play a crucial role in understanding how workers’ behaviors can be aligned with the need to keep food safe and provide guidance for ways in which behaviors in organization can be modified to achieve desired outcomes.

Resumen

Brotes recientes de enfermedades relacionadas con los alimentos han atraído una mayor atención a proteger los alimentos de la contaminación. Aproximaciones psicológicas a las conductas durante el procesamiento de alimentos pueden contribuir a los esfuerzos de los trabajadores para mantener seguros los alimentos y evitar la contaminación. Este estudio examina la efectividad de la teoría de la conducta planificada (TCP) para predecir conductas de seguridad alimenticia autoinformadas de trabajadores de procesamiento de pavo. Consistente con la TCP, este estudio sugiere que la actitud hacia la conducta, la norma subjetiva, el control percibido de la conducta y la intención conductual juegan roles importantes para entender cómo prevenir contaminación con origen en los alimentos. Los resultados también muestran que los antecedentes personales, particularmente el género, pueden ser importantes para aplicar la TCP en contextos laborales específicos. Por ello, las conductas más prominentes de los trabajadores sobre la seguridad alimentaria juegan un rol crucial para entender cómo pueden alinearse las conductas de los trabajadores con la necesidad de mantener seguros los alimentos y proporcionan orientación sobre cómo pueden modificarse las conductas en la organización para lograr los resultados deseados.

Palabras clave

Seguridad alimentaria, Teor├Ła de la conducta planificada, Creencias prominentes, Influencia del g├®nero, Trabajadores de procesamiento de alimentosKeywords

Food safety, Theory of planned behavior, Salient beliefs, Gender influences, Food processing workersCite this article as: Nickell, G. S. & Hinsz, V. B. (2023). Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand WorkersŌĆÖ Production of Safe Food. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 39(2), 89 - 100. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2023a10

Correspondence: Verlin.Hinsz@NDSU.edu (V. B. Hinsz).

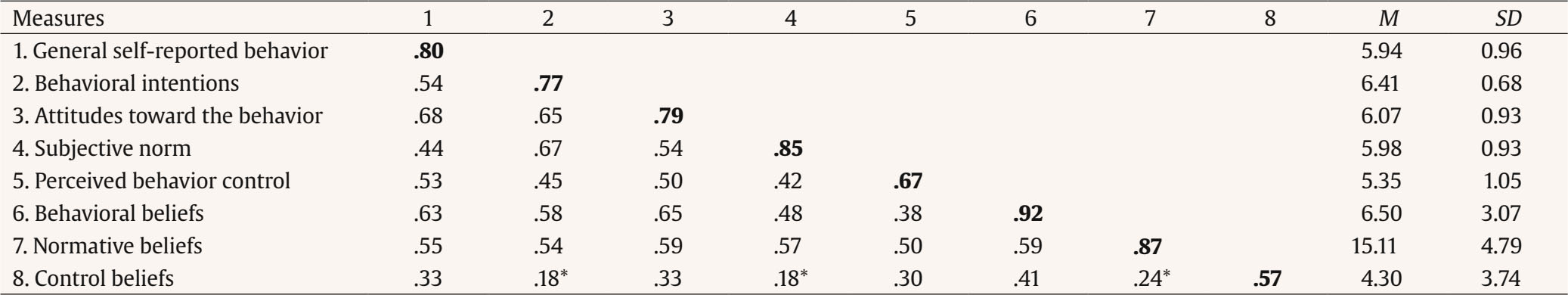

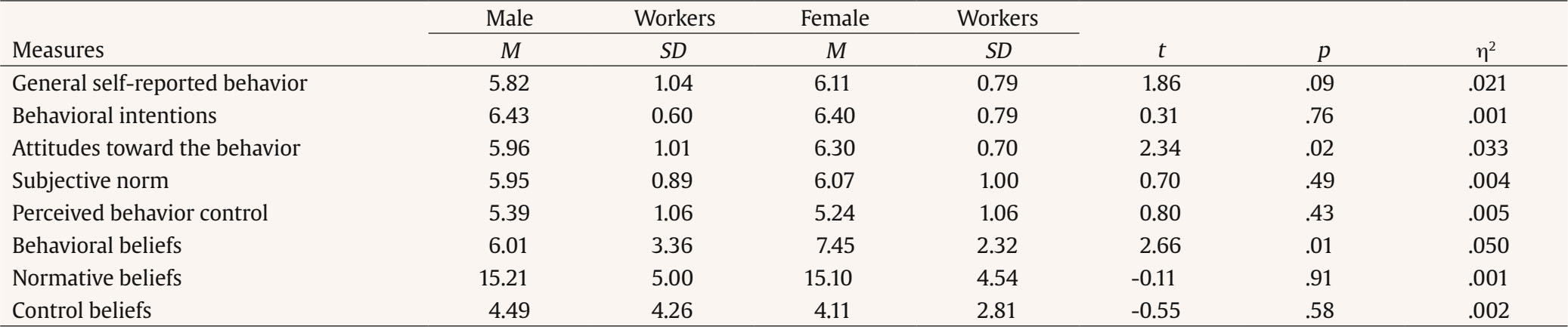

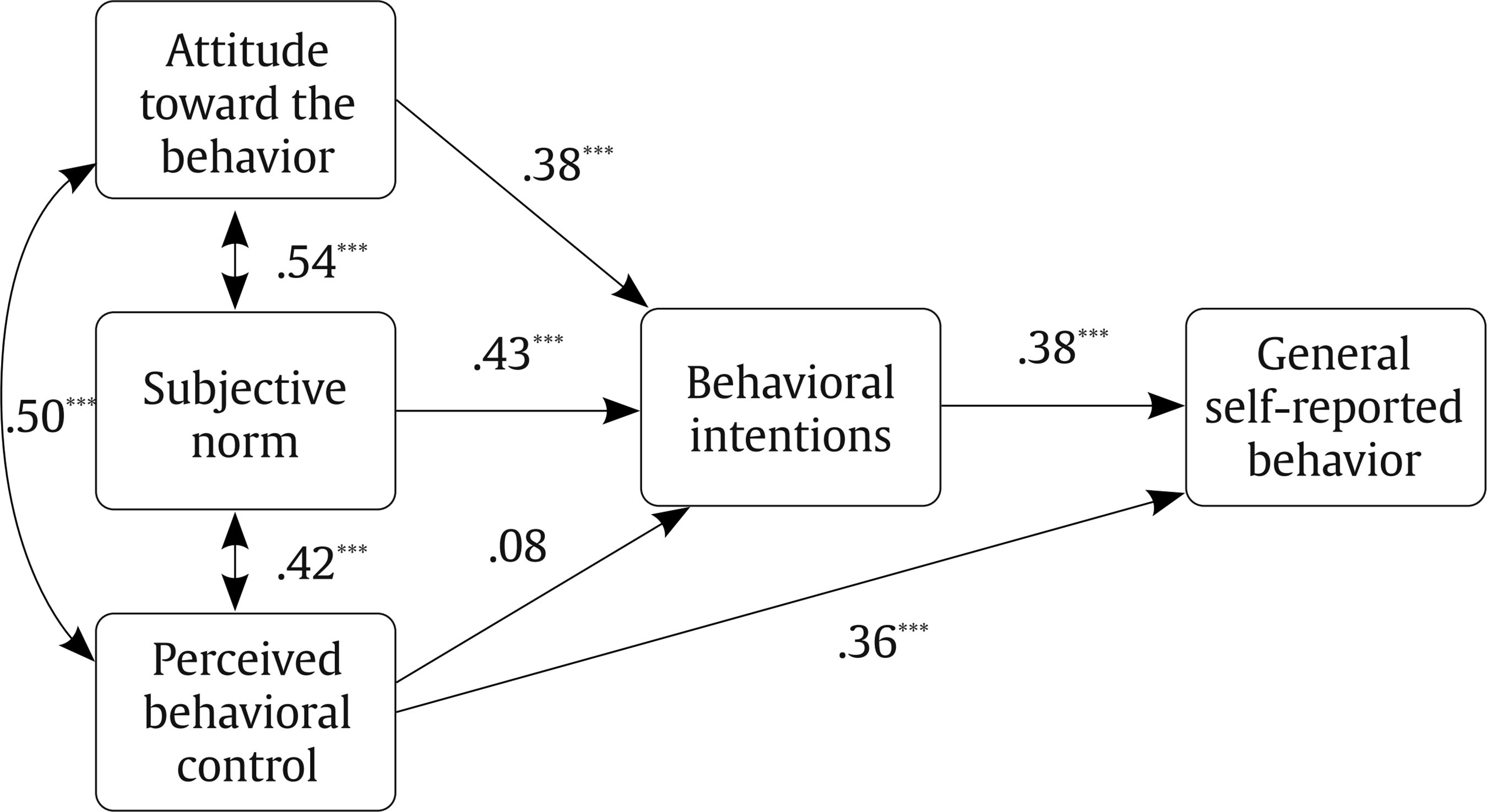

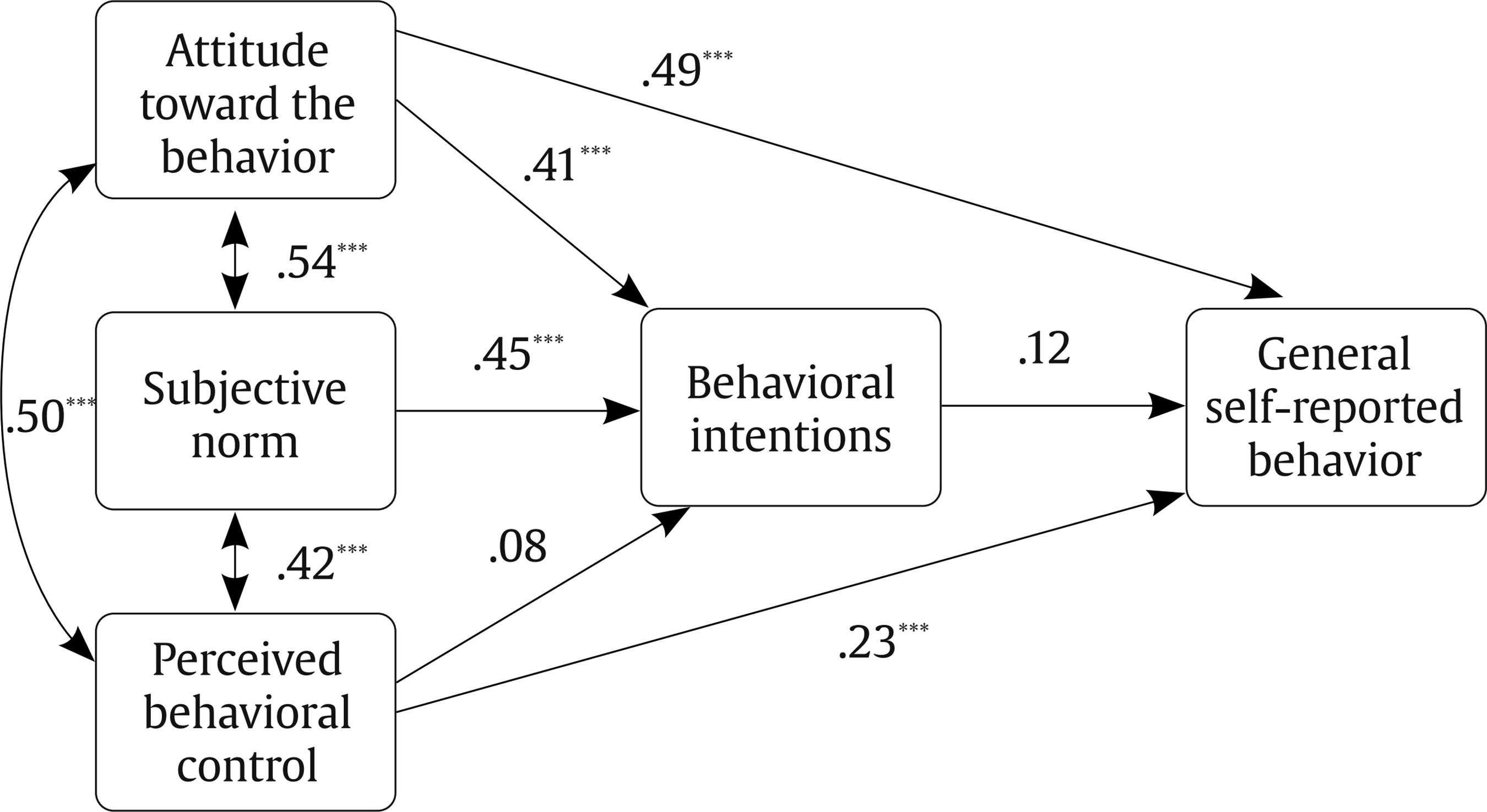

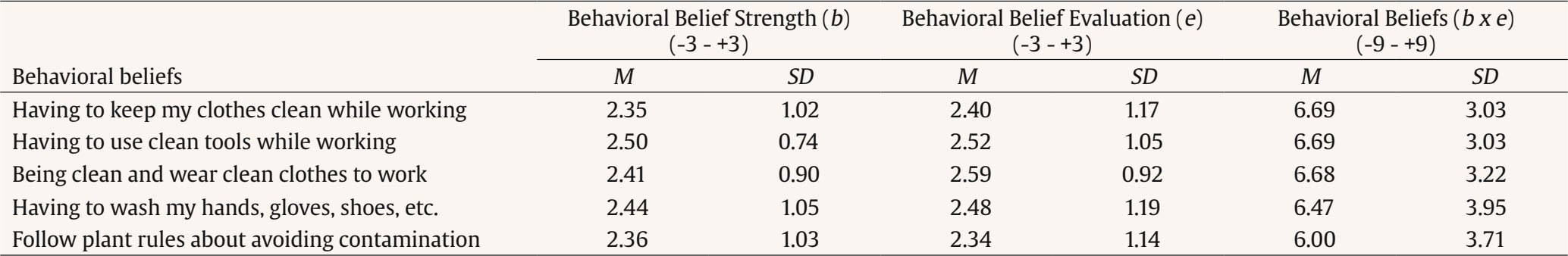

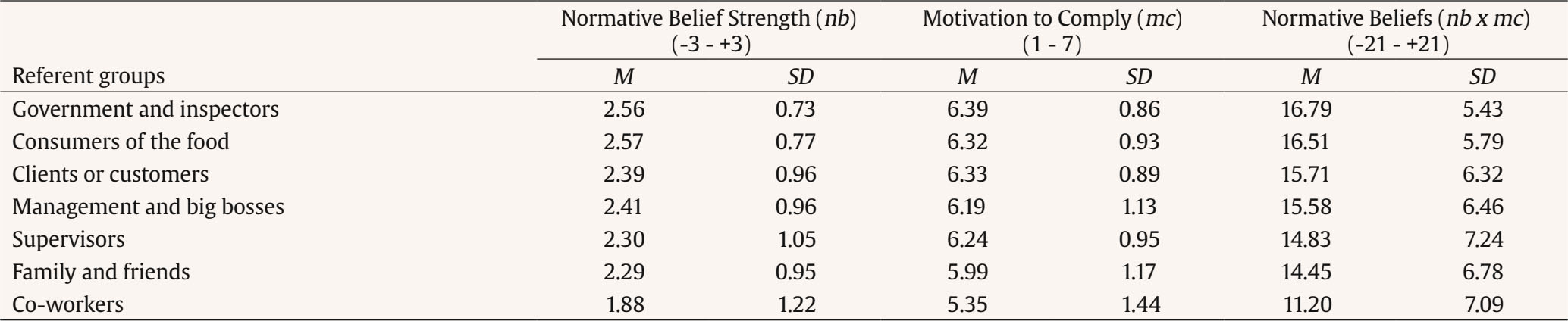

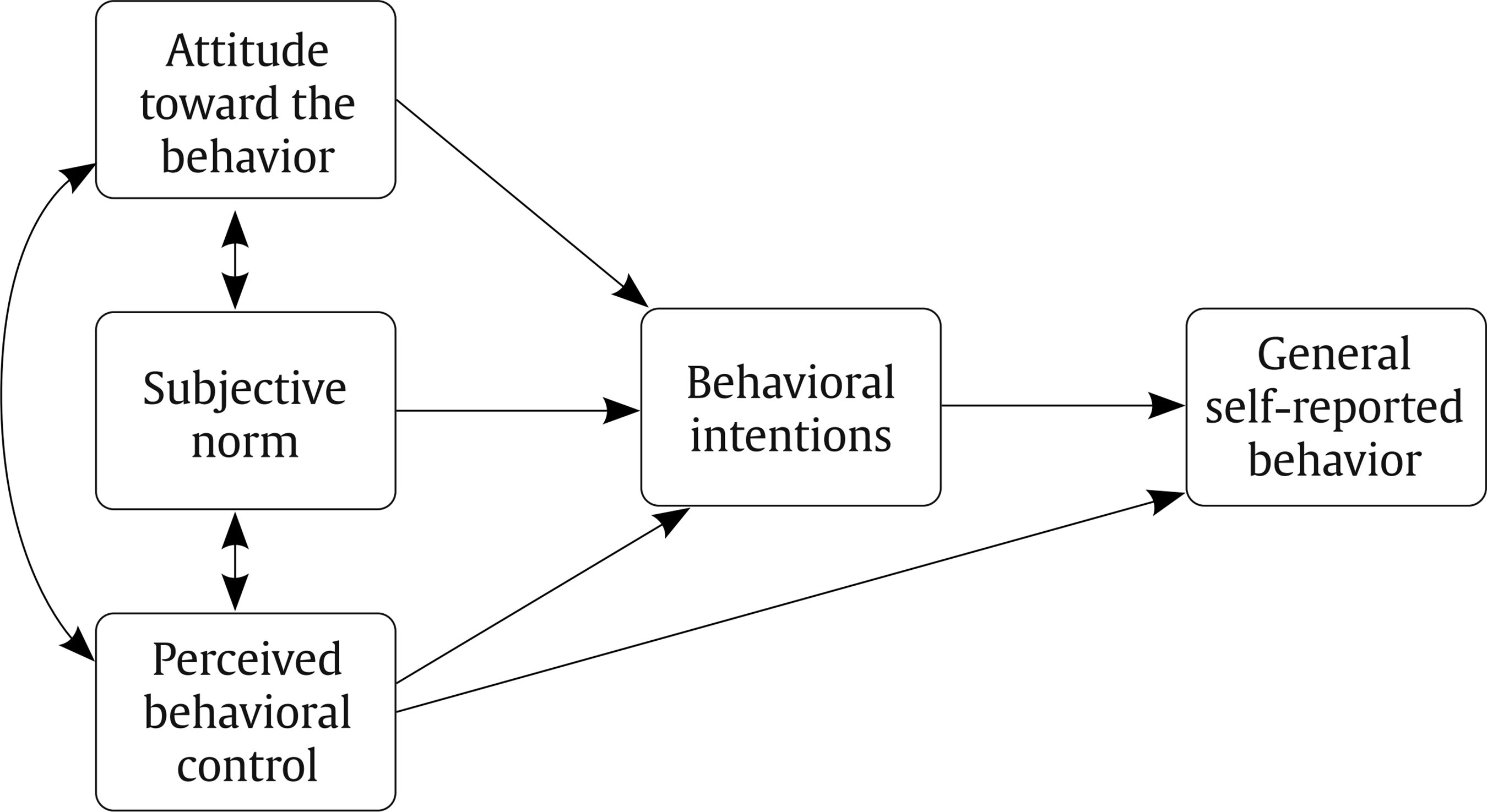

Recent food contamination incidents highlight why the production of safe food is an important organizational concern. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, in 2010 there were 389,000 workers involved in food processing, and food safety is an essential function of each of these jobs. The consequence for consumers, organizations, and employees is very significant when food is contaminated. The Center for Disease Control (CDC, 2011) reports that in the U.S. alone 48 million people become sick each year with approximately 3,000 deaths each year because of food contamination. Food production organizations involved in food contamination incidents lose money due to the costs of recalling the product, lost productivity, increased insurance premiums, loss of future sales, and lawsuits. Employees in these organizations often face a loss of wages during the period immediately following a recall. For example, the 2007 Castleberry Food Company recall of canned chili due to botulism contamination was estimated to have cost the company $38 million, and production at the specific plant involved in the contamination was stopped for more than two weeks (Schmit, 2008). What can be done to combat lapses in food safety? This paper considers how psychological approaches applied to workers in organizations can contribute to keeping food safe and avoiding contamination (cf. Clayton & Griffith, 2003; Foster & Kaferstein, 1985; Schafer et al., 1993). Although food contamination can occur anywhere from “farm to table,” it tends to affect greater numbers of people when it occurs during food processing. For example, a 2013 salmonella outbreak at the Foster Farm chicken processing plant affected 362 people in over 21 states and Puerto Rico (CDC, 2013). Although many factors play a role in food safety in the workplace, a crucial psychological aspect is a worker’s intention to act (or not act) in ways that achieve food safety objectives. An important question is: What motivates workers to want to act to keep food safe and behave in ways to avoid contamination? Do workers’ attitudes, social norms, and intentions influence food safety work behaviors? This study applies a behavioral intentional model that incorporates work motivation constructs to determine how employees working in a food production facility can intentionally behave to keep food safe. Theory of Planned Behavio The theory of planned behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1988, 1991, 2002), which evolved from the theory of reasoned action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), is designed to predict and explain human behaviors in various specific contexts or situations. The theory of planned behavior has been one of the most popular and successful theories for predicting intentional behaviors in a variety of situations. Although demonstrated with such behaviors as weight loss, smoking cessation, and physical fitness routines (see Armitage & Conner, 2001 for review), the TPB has infrequently been applied to work behavior. In the workplace, the TPB has primarily been applied to non-production related behaviors such as exercise (e.g., Blue et al., 2001) and smoking cessation (e.g., Boissoneault & Godin, 1990; Borland et al., 1991). The TPB has infrequently been applied to other organizational behaviors such as predicting human resource managers’ intentions toward using unstructured or structured interviews (van der Zee et al., 2002). A key issue for the present study is whether the theory of planned behavior could be useful in understanding and predicting the food safety intentions and behaviors of food production workers. The production of safe food is partially an outcome of the actions and inactions of the workers involved in food production. The TPB predicts that behavioral intentions and perceived behavioral control ultimately predict whether workers would or would not engage in these actions. As illustrated in Figure 1, the TPB proposes that three conceptual variables independently predict behavioral intentions. The three variables or components are attitude toward performing the behavior, subjective norm for performing the behavior, and perceived control over the behavior. These three components are also generally correlated with each other. Each of these components will be briefly described in relation to their relevance to workers’ actions in the workplace. In addition, these three variables are determined by underlying behavioral, normative, and control beliefs. The critical role that beliefs play in explaining the antecedents of behavior is also described below. Behavioral Intention An essential feature in the TPB is a worker’s intention to perform a specific behavior. According to the TPB, intention is a proximal cause of behavior. Intentions are an individual’s desires, plans, and willingness to engage in a focal behavior. Intentions reflect important aspects of motivation because they are indications of how much effort workers are planning to put forth and how hard they are willing to strive in order to achieve a particular behavior (Ajzen, 1991). The TPB assumes that these intentions reflect motivational factors that affect behavior – the stronger the intention to perform a behavior, the more likely the person will engage in the behavior. Attitude Toward the Behavior The attitudes we carry about with us represent our thoughts and feelings toward specific objects and social entities (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). Similarly, we also have these thoughts and feelings regarding engaging in specific behaviors (i.e., attitude toward the behavior; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). We can have positive or negative (e.g., favorable-unfavorable, pleasant-unpleasant, good-bad) evaluations of engaging in these behaviors. If a worker has a negative attitude toward engaging in a behavior, he or she will be less likely to engage in that behavior. For example, if workers believe that frequently washing their hands is unpleasant, they will be less likely to do so. This attitude reflects one critical factor that determines a worker’s intentions as well as the subsequent likelihood to perform the behavior. Subjective Norm The subjective norm component reflects the reality that our behavior is influenced by a variety of social forces. We perceive pressures from others that are important to us to engage or not engage in particular behaviors. If we believe that many of the people who are important to us (e.g., co-workers, supervisors) think that we should not engage in a particular work behavior, we are less likely to do so. However, for these subjective social pressures to influence our behavior, we have to be motivated to comply with what we believe are the wishes of these important others. For example, even if the Department of Agriculture inspector and my supervisor have repeatedly told me not to wipe my knife on my apron, I might do so anyway because I do not really care to act in ways these others want me to act. So, in order to understand and predict a person’s intentions and behaviors, we need to know how the person perceives the social pressures. Perceived Behavioral Control Another influence on our intentions to act is our view of our capability to engage in the behavior called perceived behavioral control. If we believe that we can effectively engage in the behavior, then we are more likely to engage in the behavior. In addition, there is a link between perceived behavioral control and intentions. If we perceive we do not have the power or competence to engage in the behavior, then we are less like to intend to perform the behavior. Ajzen (1991) asserts that intentions can influence behavior only if the behavior is under volitional control. If we do not believe that we can successfully engage in the behavior, then we might not intend to do so. Perceived behavioral control is posited to directly predict behavior when volitional control of the behavior is lower (see Figure 1). Thus, if a worker believes that he or she cannot do anything to keep the food safe, then the worker is less likely to act in ways to keep the food safe or intend to do so. Salient Beliefs The beliefs that individuals hold play a crucial role in the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Ajzen suggests that beliefs are the informational foundation of behavior and that the determinants of behavior can be traced ultimately to these beliefs. Thus, at the primary level of explanation, behavior is a function of the beliefs that are relevant to the behavior that are salient to an individual. Ajzen proposes a set of salient beliefs correspond to each of the critical TPB concepts: behavioral beliefs which are expected to influence attitudes toward the behavior, normative beliefs which are expected to influence subjective norms, and control beliefs which are expected to influence perceived behavioral control. These beliefs reflect an individual’s association between some attribute and the behavior (e.g., I will lose my job if I contaminate the food product. My supervisor wants me to keep the food clean. I cannot avoid contamination because of how the equipment functions). From an applied perspective, understanding these beliefs is valuable in making changes and implementing organizational interventions. If it is possible to understand the beliefs that are salient to the individuals of interest, positive modifications in behavior and desired outcomes are more likely. For example, Parker et al. (1996) designed and tested an intervention program to change underlying beliefs and attitudes to exceeding the speed limit in order to determine whether they could change driving behavior. Although these corresponding salient beliefs are not assessed in most TBP studies, in this study these beliefs were measured and used to descriptively enhance our understanding the factors underlying motivation toward safety behaviors and how these factors can be modified. Background Factors Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) note that a variety of external or background factors (e.g., age, gender, personality) are associated with beliefs and other aspects of the theory on behavior. A specific background variable will be associated with a behavior only to the extent that this background variable relates to the behavioral, normative, or control beliefs that influence the specific behavior (Ajzen, 1991). A background factor (e.g., gender) related to one behavior (e.g., hunting) may be unrelated to another behavior (e.g., use of the internet). Because our study was in a work setting, we are particularly concerned with how background factors might impact the components of the theory of planned behavior and the prediction of intentions and behavior. Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior to Food Safety There has been research investigating the theory of planned behavior in domains relevant to food safety but that does not directly examine food safety. Cook et al. (2002) extended the TPB model to predict New Zealanders’ intentions to purchase genetically modified foods by adding a self-identity construct. Their results showed that the extended model was a better fit and predictor of intentions. Cook et al. found that attitude had the greatest influence on intention. In a descriptive study, Silk et al. (2003) applied the TPB in understanding the lay public’s attitudes and thoughts associated with genetically modified foods. Using a diverse set of focus groups, Silk et al. found that the groups’ discussions reflected aspects of each of the components of the theory of planned behavior: attitude toward the behavior, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. Relevant to worker safety behavior, Levin (1999) investigated the usefulness of the TPB in predicting glove use in health care workers. Levin found that intention, attitude, and perceived risk were important predictors of glove use. Using structural equation modeling, Levin found that the TPB was an effective model for investigating glove use behavior and in reducing workers' risk to bloodborne diseases. Similarly, O’Boyle et al. (2001) used the TPB in explaining compliance to hand washing rules by nurses. O’Boyle et al. found that TPB variables predicted intention to hand wash, and intention was related to self-reported behavior. However self-reported behavior was only slightly related to actual handwashing behavior. O’Boyle et al. concluded that actual hand hygiene behavior may be more influenced by the intensity of the work activity than by internal motivational factors as measured by the TPB. The TPB has been applied specifically to food safety behavior of food preparers (Clayton & Griffith, 2003) and food service employees (Pilling et al., 2008; Roberts et al., 2008). In Stage 1 of their research, Clayton and Griffith (2003) surveyed 100 consumers regarding their beliefs about food safety practices. One of their objectives was to identify behaviors that consumers believe are important for preventing food poisoning at home. In Stage 2, Clayton and Griffith tested the key variables of the TPB in relation to actual consumer food safety behavior (handwashing, cleaning, and using different utensils). Along with a survey of their knowledge, attitudes, intentions, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, Stage 2 involved videotaping 40 participants as they prepared several meals. One finding was that none of the food preparers washed and dried their hands at all appropriate times. Also, Clayton and Griffith report a large discrepancy between intended behavior and consumer’s the actual food safety behavior. Although based on descriptive statistics, Clayton and Griffith suggest that perceived behavioral control, perceived barriers, and perceived risk may be better predictors of food safety behavior than knowledge or intention. Pilling et al. (2008) used the TPB to identify important beliefs that might improve food service workers' intentions to engage in three important work behaviors: handwashing, thermometer use, and proper sanitizing of food surfaces. Attitudes were the only consistent predictor of all three types of behaviors. Intentions to hand wash was predicted by attitudes and perceived behavioral control. Intentions to use thermometers was predicted by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Intention to sanitize food surfaces was predicted by attitudes and subjective norms. Consistent with Clayton and Griffith (2003), knowledge of food safety behaviors was not a significant predictor any of the three relevant work behaviors. Clayton and Griffith (2008) studied the hand hygiene practices of 115 food handlers at catering businesses. The hand hygiene misbehaviors were observed while they prepared food in their workplace on three different days. When these observations were completed, the food handlers completed a survey that measured variables from the TPB. They found that the TPB was a good model of hand hygiene malpractices, explaining 34% of the variance. The key components that predicted hand hygiene behavior were attitudinal beliefs, subjective norms, descriptive norms, perceived behavioral control, control beliefs, and intentions. This selective review of these different investigations of food safety behaviors finds that the components of the theory of planned behavior unsystematically and inconsistently influence the food safety intentions and behaviors. Clearly the different settings, samples, and food safety behaviors could influence the differences among the results of these studies of food safety. Moreover, Ajzen and Fishbein (1980; see also Ajzen, 2002; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) forcefully argue that differences in results can arise because of inappropriate operationalizations and measures of the key components of the theory of planned behavior. Background Factors and Food Safety A number of background factors have been shown to impact or interact with the typical TPB variables and food safety. One potentially important background factor that may influence food safety beliefs is gender.1 Gender has been found to be an important determinant of risk perception across a range of health and environmental risks and concerns (Flynn et al., 1994). Finucane et al. (2000) showed that women perceived food risks higher than men and also found similar gender differences for behavioral intentions. Dosman et al. (2001) found women were more concerned about food safety risks in the home than men. However, McIntyre et al. (2013) reported no gender differences in food safety knowledge, attitudes and self-reported hand washing practices in a study of trained and untrained restaurant food handlers. Most food safety studies using the TPB as a model have not reported whether gender had an impact on the results. Given the general trend for women to be more involved in food processing and cooking in the home, and for women to show more concern for health issues such as healthy food, it is plausible that women would differ from men in important ways in the safe production of food during processing. Thus, this study will investigate whether gender influences components of the theory of planned behavior with regard to the production of safe food. Current Study The present study goes beyond previous research that has applied the TPB to work-related settings by testing the theory with an important but often neglected group of workers, namely food processing employees. The purpose of this research is to examine the effectiveness of the TPB in explaining and predicting the product safety behaviors of employees of a turkey processing plant (see Figure 1). Attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived control are hypothesized to predict the intentions to engage in food safety behaviors. The more favorable the workers’ attitude and subjective norms and the greater the perceived behavioral control, the stronger the intention to produce safe foods. Research has demonstrated that the components of the TPB have been predictive in domains outside of food safety (Ajzen, 1988; Ajzen & Madden, 1986; Hinsz & Nelson, 1990; Hinsz & Ployhart, 1998) and it is expected that these components will also predict intentions with regard to workplace food safety behaviors. Secondly, as volitional control over the food safety behavior declines, perceived behavioral control should be more useful in predicting self-reported food safety behavior. Thus, based on the TPB, we hypothesize that behavioral intention and perceived behavioral control will predict self-reported food safety behavior. In the context of investigating the components of the theory of planned behavior, we also investigate food processing workers' beliefs have toward food safety. Because of the critical nature of workers in avoiding contamination, it will be informative to uncover the beliefs of the workers that impact the components of the theory of planned behavior. Moreover, because background factors are expected to influence the factors believed to predict intentions and behaviors through these beliefs, the assessment of workers’ beliefs will allow us to explore how gender influences the psychological factors associated with producing safe food. Work Site Approximately 300 workers were employed at a fully integrated turkey processing plant located in a town in the U.S. upper Midwest. Live turkeys were brought to the plant from twelve different suppliers in three states. The plant processed and distributed over 200 standard turkey products to school districts, food service management companies, distributors, colleges, and universities, and government agencies. Pilot Study In order to develop a list of salient behavioral, normative and control beliefs, as well as facilitate the development of the final questionnaire, the authors conducted approximately 10-minute interviews with 42 employees (23 males and 19 females) at the plant (see Nickell & Hinsz, 2009). Prior to the worker interviews, an extensive interview was conducted with the human resource/safety manager as well as a tour of the plant to gain a better perspective of the workers’ tasks and their relation to food safety. Participants Two hundred sixty-one turkey processing plant workers were given the opportunity to take home a questionnaire to be returned several days later. The 261 employees included 243 full-time workers and 18 temporary employees. The company announced the upcoming questionnaire one week before the questionnaire was made available. The 261 potential respondents included all plant workers and first-line supervisors, with the exception of managers and front-office personnel. One hundred eighty-nine workers (72% of the workforce) took a questionnaire to be completed at home. One hundred forty workers (54% of the workforce, 74% of those who took a questionnaire) returned their questionnaire to the researchers and were paid $15 for completing it. Because approximately 45 employees were primarily Spanish speaking, a Spanish-language version of the questionnaire was constructed and provided to those individuals as an option. Seventeen Spanish-version questionnaires were taken and 12 were returned. The mean age of respondents was 39.32 (range = 18-73 years). Respondents had worked for the plant an average of 7.40 years (range = 0.04-36.00 years). The gender of the respondents (86 males, 49 females, and 5 unspecified) was also fairly representative of the actual workers (p = .43). Males made up 67.8% of the workforce and 61.4% of the respondents. For the questionnaire, we used seven categories of race and ethnicity based on federal guidelines (OMB Statistical Directive 15, 1997): American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, White, and other. White workers account for 71.6% of the workforce and 70.7% of the respondents. Four questionnaires (2.9%) did not indicate the ethnic/race background of the respondent. Overall the race and ethnicity of the respondents did not significantly differ from the race and ethnicity of the overall plant workers (p = .23). All participants completed informed consent for completing the survey. Their responses to the survey were confidential. Instruments Questionnaire The questionnaire had 188 questions including some variables not reported here (e.g., stress at work). The participants reported that it took about one hour to complete the questionnaire. The questionnaire began with a two-page introduction that highlighted the purpose of the questionnaire, the $15 compensation, confidentiality of responses, definitions of the common questionnaire phrases such as ‘clean and uncontaminated turkey products’ and ‘doing all that is needed to produce clean and uncontaminated turkey products’ (i.e., the behavior of interest), as well as the procedure for returning the questionnaire for compensation. General instructions for completing the various rating scales were provided along with sample questions and potential responses (cf. Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). The measures of the conceptual variables of interest were developed based on the recommendations included in the appendix of Ajzen and Fishbein (1980). Most items noted below were assessed on 7-point semantic differential (e.g., 1 = extremely unlikely to 7 = extremely likely) and Likert-type response scales (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) although a number of other response scales were also used. For each of the measures constructed, acceptable internal consistency coefficients (.67 to .92) (see diagonal on Table 1) supported constructing composite scores from the mean of the item responses. Table 1 Intercorrelations, Coefficient Alphas, Means, and Standard Deviations for Components of the Theory of Planned Behavior   Note. Internal consistency alpha coefficients are presented in boldface along the diagonal. All correlation coefficients are significant at p < .001 unless noted with a *p < .01). Demographic Questions Demographic questions included the respondent’s gender, age, race/ethnic background, education level, primary language, work tenure, employment status, job title, and primary work location in the plant. General Self-reported Behavior It was not possible to measure actual worker food safety related behaviors in this plant because employees were engaged in different activities in different departments throughout the plant. In addition, plant management would not allow us to videotape or systematically observe the behaviors of the workers. Therefore, general self-reported behaviors were used as a proxy for actual behavior. General self-reported behaviors were measured with five items (α = .80). For example, ‘How often do you do all that is needed to produce clean and uncontaminated turkey products?’ (1 = never to 7 = always). Behavioral Intention Behavioral intentions were measured with five items, each on 7-point (1 to 7) response scales (α = .77). The items were: “I (want/ intend/ plan/ desire) to do all that is needed to produce clean and uncontaminated turkey products” (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree), and “How willing are you to do all that is needed to produce clean and uncontaminated turkey products?” (1 = unwilling to 7 = willing). Attitude Toward the Behavior Attitude toward the behavior was measured with five semantic differential responses (e.g., 1 = extremely bad to 7 = extremely good) to the same statement “My doing all that is needed to produce clean and uncontaminated turkey products is,”. Participants responded to the semantic differential items of good-bad, pleasing-annoying, favorable- unfavorable, important-unimportant, enjoyable-unenjoyable, and one additional item (I like/dislike), providing a high level of internal consistency (α = .77). Subjective Norm A global measure of subjective norms was measured with five items, each on a (1 to 7) Likert-type scale (α = .85). For example, “Most people who are important to me think I should do all that is needed to produce clean and uncontaminated turkey products,” (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Perceived Behavioral Control Perceived behavioral control was measured with five items. For example, “Even if I wanted to, it would be difficult for me to do all that is needed to produce clean and uncontaminated turkey products” (7 = strongly disagree to 1 = strongly agree). Although the internal consistency of the perceived behavioral control measure (α = .67) was lower than the other components of the theory, Cheung and Chan (2000) report a meta-analysis of 90 studies finding that the average perceived behavioral control internal consistency was .65 (Ajzen, 2002). None of the items used in this study were identified as the culprit for the lower internal consistency, so all five items were included in the composite score. Behavioral Beliefs Behavioral beliefs consisted of two components: the perceived likelihood of an outcome of the behavior and the evaluation of the outcome. Thus, measures of behavioral beliefs were obtained by multiplying the behavioral belief strength (b) (e.g., ‘My doing all that is needed to produce clean and uncontaminated turkey products means I always have to wash my hands, gloves, shoes, and so on at work’) by the behavior belief evaluations (e) (e.g., ‘My always having to wash my hands, gloves, shoes, and so on at work is’ – good/bad). Consistent with the recommendation by Fishbein and Ajzen (2010), the behavioral belief strength items were scored using a (-3 = strongly agree to +3 = strongly disagree) scale, while the evaluations (e) items were scored using a (-3 = bad to +3 = good) scale. Scores for each of the five pairs of behavioral belief items ranged from –9 to +9. Ajzen (2002) notes that because belief-based measures depend on accessible beliefs produced by the research population, the question of reliability is not as relevant or appropriate compared to the other components of the theory. Normative Beliefs Normative beliefs consisted of two multiplicative components: normative belief strength (nb) and motivation to comply (mc). Normative beliefs involve the perception that specific significant others believe the person should perform the behavior or not (e.g., “My supervisors think I should do all that is needed to produce clean and uncontaminated turkey products”). Motivation to comply (mc) involves the willingness to comply with the desires of specific significant others (e.g., “Generally speaking, I want to do what my supervisors think I should do”). Consistent with the recommendation by Fishbein and Ajzen (2010), a measure of normative beliefs as obtained by multiplying nb x mc for seven pairs of beliefs that were generated from the pilot study. The normative belief strength (nb) items were scored using a (-3 = strongly disagree to +3 = strongly agree) scale while the motivation to comply (mc) items were scored using a (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) scale. Scores for each normative belief could range from –21 to +21. Control Beliefs Control beliefs reflect a person’s belief about their level of control over behavior. A measure of control beliefs was obtained by multiplying the control belief strength (c) (e.g., “How ‘often’ do you have the training you need to produce clean and uncontaminated turkey products?”) by the control belief power (p) (e.g., “My having the training I need makes producing clean and uncontaminated turkey products easy/difficult”) for the 10 pairs of control beliefs. Consistent with the recommendation by Fishbein and Ajzen (2010), the control belief strength items were scored using a (1 = never to 7 = always) scale while the control belief power items were scored using a (-3 = extremely difficult to +3 = extremely easy) scale. Scores for each belief could range from –21 to +21. Table 1 shows the intercorrelations, means and standard deviations for the main theory of planned behavior (TPB) components. Although all components of the model were rated above the scale midpoint by the workers, the level of perceived behavioral control was moderate (M = 5.35) in comparison to the other components. Pearson correlations were computed to examine expected interrelationships among the key components of the TPB (see Figure 1). As expected and presented in Table 1, correlational analysis showed significant interrelationships among all key components of the TPB. Attitudes toward food safety behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control were all strongly related to behavioral intention. In addition, behavioral intention and perceived behavioral control were significantly correlated with general self-reported behavior. Each of the salient belief components (behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs, and control beliefs) were strongly correlated with their corresponding component (i.e., attitude toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control). In addition, Table 2 and 3 summarize the differences between male and female workers for the main TPB variables. Table 2 presents the intercorrelations among the TPB variables divided along the diagonal for female and male survey respondents. It is instructive to note that the intercorrelations among the TPB variables were generally higher for males than for those of females. As shown in Table 3, a gender difference was found for attitude toward the behavior, t(133) = 2.34, p < .02, partial η2 = .033. Female workers (M = 6.3) had a more positive attitude toward food safety behavior than did male workers (M = 5.96). A gender difference was also found for overall mean of the behavioral beliefs, t(133) = 2.66, p < .01, partial η2 =.05. Female workers (M = 7.45) had a stronger combination of behavioral belief strength and evaluations than did male workers (M = 6.01). There were no significant relationships for age, race, or work tenure on intentions or self-reported behavior. Table 2 Intercorrelations for Components of the Theory of Planned Behavior by Gender   Note. Correlation coefficients for female respondents (n = 49) are below the diagonal and male respondents (n = 86) are above the diagonal. All correlation coefficients are significant at p < .01 unless noted with a *p < .05 or +p > .05). Table 3 Means and Standard Deviations, t-tests, and Effect Sizes for Components of the Theory of Planned Behavior by Gender   Regression Analyses Multiple regression analyses are commonly used in TPB research to analyze the data (Armitage & Conner, 1999). Regression analyses were used to test the contributions of attitude toward the behavior, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control to the prediction of behavioral intentions. Attitude toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control were entered into the regression equation simultaneously and together account for 57% of the variance for behavioral intentions, F(3, 136) = 59.49, p < .001. The regression analysis indicates that attitude toward the behavior (β = .37, p < .001) and subjective norm (β = .43, p < .001) each made significant contributions to the prediction of behavioral intention, but perceived behavioral control did not, β = .08, p = .23. In addition, we examined whether behavioral intentions and perceived behavioral control significantly predict general self-reported behavior. Consistent with the theory of planned behavior, behavioral intention (β = .38, p < .001) and perceived behavioral control (β = .36, p < .001) made significant contributions to predicting general self-reported behaviors, F(2, 137) = 44.27, p < .001, accounting for 39% of the variance. Path Analyses Given the general confirmation for the relationships we hypothesized for intentions and self-reported behavior, we attempted to examine how well the TPB illustrated in Figure 1 would account for the employees’ responses using path analysis. Because in path analysis there should ideally be ≥ 20 subjects per parameter (e.g., Klem, 1995), salient beliefs are not included. A path analysis conducted to test these relationships found the TPB model as depicted in Figure 1 did not fit the set of responses very well, χ2(2) = 27.36, p < .001, RMSEA = .311, CFI = .90, SRMR =.066, GFI = .92, AGFI = .43 (standardized coefficients are presented in Figure 2). As predicted by the theory of planned behavior, subjective norms and attitudes toward the behavior had indirect effects on self-reported behavior through behavioral intentions. Figure 2 Path Analysis with Standardized Path Coefficients for the Theory of Planned Behavior.   ***p < .001. One outcome of the path and regression analyses is that perceived behavioral control did not predict intentions, which is not inconsistent with theoretical expectations for some behaviors (Ajzen, 1991). So, a revised model was constructed which deleted this relationship. In addition, previous research indicates that the attitude toward the behavior sometimes has a direct effect on behavior in addition to the indirect effect through intentions (Bentler & Speckart, 1979, 1981). This direct effect of attitude to behavior was also added to the revised model, which is presented in Figure 3. A path analysis of this revised model indicates it is a very good fit to the data, χ2(2) = 1.42, p =.49, RMSEA = .000, CFI = 1.00, SRMR = .015, GFI = 1.00, AGFI = .97 (coefficients for the revised model are presented in Figure 3). Consistent with the regression analysis, intentions were predicted by the attitude and subjective norm components, but not by perceived control. However, self-reports of behavior were predicted by perceived control and attitude toward the behavior, but it was not directly predicted by intentions as predicted by the TPB. Figure 3 Refitted Path Analysis with Standardized Path Coefficients for the Revised Model.   ***p < .001. We were concerned that this revised model did not show a significant coefficient between the intention and the self-reported behavior. The relationship between intentions and behavior is a centerpiece of the theory of planned behavior. However, the revised model did include a link between attitude toward the behavior and self-reported behavior which is not consistent with the theory of planned behavior. Because we had found an effect of respondent sex on the attitude toward behavior component, it might be possible that workers’ gender impacts the relationships of the components such as intentions on self-reported behavior. Because our sample size was too small to conduct a multi-sample path analysis, we conducted an additional path analysis which included workers’ gender with paths to attitude toward the behavior, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and intention. This model including workers’ gender also had an adequate fit, χ2(3) = 4.73, p = .19, RMSEA = .067, CFI = 1.00, SRMR = .027, GFI = .99, AGFI = .92. As expected, from the correlation matrices presented in Tables 1 and 2 as well as the results presented above, gender had a significant coefficient with the attitude toward the behavior component (-.19) and the behavioral intention component (.12). Additionally, in this path analysis the path between behavioral intention and self-reported behavior was significant (.20) as is predicted by the theory of planned behavior. Consequently, although the revised model did not show a significant path from behavioral intention to self-reported behavior, once the unique contributions of workers’ gender to this model are considered, one can better understand why the coefficient between intention and behavior was not significant in the revised model. Behavioral Beliefs In the pilot interviews, five important behavioral beliefs were identified by many employees. Behavioral beliefs reflect a worker’s perception that engaging in specific behaviors (e.g., wearing clean clothes to work) will lead to avoiding food contamination. The mean scores for each behavioral belief are shown in Table 4 in order of importance. All of the behavioral beliefs are relatively strong. Although still strong, the weakest behavioral belief involved the workers’ perception that following plant rules would avoid contamination. Importantly, the sum of the behavioral beliefs was significantly correlated with the measure of the attitude toward the behavior (Table 1). Table 4 Means and Standard Deviations for Behavioral Beliefs Strength, Behavioral Belief Evaluation for each Behavioral Belief   Table 5 Means and Standard Deviations, t-tests, and Effect Sizes for Specific Behavioral Beliefs by Gender   Table 6 Means and Standard Deviations for Normative Belief Strength, Motivation to Comply and Normative Beliefs or each Referent Group   A gender difference was found for the mean of all five behavioral beliefs as noted earlier. Consequently, we examined each salient behavioral belief to determine if gender differences arose for these beliefs. For four of the five behavioral beliefs, female workers had significantly stronger behavioral beliefs (see Table 5). These gender differences in the behavioral beliefs provide a basis for understanding why a gender difference was found for the measure of the attitude toward the behavior. Female workers had much stronger beliefs about the impact of different behaviors on avoiding contamination of the food products. Consistent with our earlier speculation, females had stronger attitudes toward the value of food safety actions and had stronger beliefs that specific behaviors will contribute to food safety. Mediation of Gender Effect by Beliefs Conceptually, the effects of external factors such as workers’ gender on components in the theory of planned behavior are predicted to be mediated by the beliefs associated with those components (or the relative weighting of the components in the prediction of intentions). Because workers’ gender was found to impact the measure of the attitude toward the behavior, we sought to test whether this gender effect was mediated by the behavioral beliefs associated with the attitude toward the behavior component. Consistent with Baron and Kenny (1986), we first found that workers’ gender was a significant predictor of the attitude toward the behavior measure, β = -.18, F(1, 132) = 4.48, p < .04, R2 = .03. Similarly, but with a much stronger relationship, the sum of the behavioral beliefs was a significant predictor of the attitude toward the behavior measure, β = .65, F(1, 132)= 97.90, p < .001, R2 = .43. Additionally, workers’ gender was a significant predictor of the sum of the behavioral beliefs, β = -.22, F(1, 132) = 6.88, p < .01, R2 = .05. When the regression on attitude toward the behavior was conducted with both workers’ gender and the sum of behavioral beliefs as predictors, workers’ gender was no longer a significant predictor, β = -.04, t(131) = 0.56, p > .57, while behavioral beliefs remained a significant predictor, β = .64, t(131) = 9.50, p < .001. Consequently, this analysis supports the prediction that the effect of the external factor of workers’ gender on the attitude toward the behavior component was mediated by the beliefs associated with that component. Normative Beliefs Perhaps the most interesting salient beliefs in the current study were the normative beliefs. In the pilot interviews, seven important referent groups were identified by many employees. Normative beliefs involve the perception that specific meaningful others (referents) believe the person should perform the behavior (or not) multiplied by the motivation to comply with the perceived desires of these meaningful others. The mean scores for each referent group are shown in Table 6 in order of importance. The strongest normative beliefs strength and motivation to comply came from the government (USDA) and company inspectors (M = 16.79) closely followed by consumers or the people who eat the products (M = 16.79). The importance of consumers was expected because most employees were aware that a large percentage of their turkey products go to school lunch programs. From the pilot interviews, co-workers as a referent group was mentioned more often than any other group. However, using pair t-tests, the results show that normative beliefs score for co-workers (M = 11.20) was significantly lower than all 6 other reference groups (ps < .001). Given notions about the value workers put on information from co-workers (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1977) and general media accounts of the dislike of regulators and government inspectors, it is somewhat surprising that normative beliefs about inspectors were significantly stronger than those associated with co-workers. Table 7 Means and Standard Deviations for Control Beliefs Strength, Control Belief Power for each Control Belief   Control Beliefs Control beliefs reflect a person’s belief about their perceived level of control over performance of a specific behavior. The mean scores for each control belief are shown in Table 7 in order of level of control. Control beliefs are scored such that higher values indicate that the workers perceived more control over conditions positively associated with engaging in food safety behaviors. Workers had stronger control beliefs for behaviors directly associated with keeping things clean (i.e., use of sanitizing products, clean work garments, clean equipment). These workers did not perceive they have much control with regard to distractions, proper supervision, being too busy, being too tired, or knowing the rules. Other than keeping things clean, the control beliefs did not fit well into categories. These control beliefs appear to represent a diverse set of factors that could facilitate or hinder the workers’ beliefs that they could do what was necessary to keep the turkey products safe from contamination. In the interviews with the workers and their survey responses, we found that 10 different control beliefs were most salient. Given that the employees worked in different areas of the plant and performed various tasks, it is perhaps not surprising that such a large number of control beliefs emerged. Moreover, because perceived behavioral control may have meant many different things to the workers performing different kinds of tasks, it is perhaps not surprising that the internal consistency for the perceived behavioral control measure did not attain the level of the other components of the TPB. Nevertheless, with the exception of the beliefs associated with keeping things clean, these control beliefs do reflect some idea of the factors that the workers in a food processing plant felt influenced their production behavior (e.g., training, distractions, fatigue, knowledge, supervision). These might be the same factors that could be considered as control beliefs for safety in other kinds of industrial production. In this study, the theory of planned behavior (TPB) was applied to the food safety intentions and self-reported behavior of food processing workers. This study demonstrated that the theory of planned behavior can be very useful for understanding the determinants of food safety behaviors. The correlational analysis showed that the components of the theory of planned behavior correlated with behavioral intentions as well as self-reports of engaging in safe food production behaviors. Importantly, the data gathered from this workplace setting indicate that there is good reason to assess workers’ beliefs when attempting to understand the reasoning behind their actions at work. Regression analyses were also supportive of the assertion that behavioral intentions and perceived behavioral control were significant in predicting food safety behaviors. Additionally, consistent with the approach underlying the theory of planned behavior, both attitude toward the behavior and subjective norm were predictive of behavioral intentions. All of these results provide additional evidence that the theory of planned behavior provides a useful framework for considering the factors that influence work motivation, and particularly for safety behaviors related to food production. The results of the regression analyses show general support for the utility of the TPB to predict behavioral intentions and general self-reported food safety behavior of turkey processing workers. The results of the path analyses, while generally supportive, could not confirm the model as initially specified in Figure 1. Rather, the best fitting model from the path analysis included a link from attitude to behavior. Although the prediction of behavior from attitudes is consistent with some of the attitude literature (Bentler & Speckart, 1979, 1981), the theory of planned behavior expects that attitudes influence behavior through behavioral intentions. One potential reason for the incorporation of the attitude component in the direct prediction of behavior is that both measures were self-report assessments made at the level of a general pattern of behavior. If a direct assessment of food safety behaviors would have been possible, it might have revealed that intention, and not attitude toward the behavior, would have directly predicted the actual behavior. In support of the TPB, attitude toward behavior, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control together accounted for 57% of the variance in behavioral intentions. This is much stronger than the 39% from meta-analytic findings of 154 studies (Armitage & Conner, 2001). As expected, attitude toward the behavior and subjective norm both predicted behavioral intention; however, the correlation between subjective norm and behavioral intention (r = .67) was much stronger than in past studies. One reason for these higher coefficients could be that many of the measures had higher levels of reliability which may have resulted from the use of multiple items. Meta-analyses (e.g., Ajzen, 1991; Armitage & Conner, 2001) have generally found that the use of multiple items to measure subjective norm significantly increased the strength of the relationship between subjective norm and behavioral intention, compared to when subjective norm was measured by a single item (r = .34; Armitage & Conner, 2001). Alternatively, the subjective norm may have a more important role for safety related behaviors. For example, during our pilot interviews, several workers noted that they were very concerned about food safety because some of their product goes into the school lunch program for children. Although perceived behavioral control was significantly correlated with behavioral intention (r = .45), it did not predict behavior intention in the regression analysis. Armitage and Conner (2001) found that perceived behavioral control enhanced the prediction of intention by 6% over and above the attitude and subjective norm, yet some studies have not found this effect (e.g., Meyers, 2002). Perceived behavioral control was added to the theory (originally called the theory of reasoned action; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) to account for situations in which people lack volitional control over the behavior. Ajzen (1991) describes how volitional control can facilitate or hinder how perceived behavioral control predicts behavioral intention and behavior, and that these relationships are expected to vary across situations and different behaviors. When the situation and the nature of the behavior allow a person to have extensive control over the performance of the behavior, perceived behavioral control is more likely to predict behavioral intention and less likely to predict behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Consequently, it is not surprising that in this study, in which the workers had limited and varying perceived control over keeping the turkey products safe, perceived behavioral control would have an influence on self-reported food safety behavior, but have a limited impact on the behavioral intention component of the model. Additionally, Ajzen (2002) notes that the measurement of perceived behavioral control remains a concern. The moderate level of internal consistency for perceived behavioral control in the current study may reflect this issue which may have contributed to the finding that perceived behavioral control was not significantly predictive of behavioral intentions for food safety. The inspection of the control beliefs indicates that the workers did not believe they had overwhelming control over food safety behaviors. Overall, based on the regression analyses, the result for predicting general self-reported behavior from behavioral intentions and perceived behavioral control (R2 = .39) compares favorably to past studies of the TPB (R2 = .32; Armitage & Conner, 2001). The correlation between behavioral intention and general self-reported behavior was .54 in this study is comparable to the results reported across 48 studies used in Armitage and Conner’s meta-analyses (r = .47). Moreover, the correlation between perceived behavioral control and general self-reported behavior in the current study (r = .53) was similar to their meta-analysis that only included studies with self-reported behavior (r = .55). The theory of planned behavior highlights the role of salient beliefs as elementary determinants of behavior. As this study demonstrates, an inspection into workers’ beliefs provides insight into the outcomes, reference groups, and controlling factors the workers associate with performing behavior, in this case the behaviors needed to keep turkey products safe and uncontaminated. Moreover, the approach outlined by the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) and the theory of reasoned action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) suggests that the way in which behaviors can be established, changed, and modified is through these beliefs. If an organization wants to establish the proper attitudes toward food safety, it might first direct efforts at training workers so that they have strong beliefs about the positive outcomes that arise from producing safe food products. And to encourage the workers to have good intentions to produce these safe food products, it would also be wise to remind the workers that the people that they care about want them to produce safe food. Importantly, the organization will also need to produce the conditions for the workers so that they believe that they can do what is necessary to keep the food clean and uncontaminated. The theory of planned behavior suggests that to produce interventions in the workplace so that the desired behaviors and outcomes are achieved it is appropriate to first direct attention to the beliefs that the workers hold about performing the behavior and the related outcomes. Behavioral beliefs are informative because they reflect workers’ perception of which specific behaviors will lead to avoiding food contamination. Various types of cleaning behaviors were perceived as important for avoiding contamination, and this perception was stronger for women workers. The one behavioral belief that was not as strong was following plant rules about avoiding contamination. Many workers do not like rules, but many food production plant rules are specifically in place to avoid food contamination. Thus, organizations need to continually reinforce the reasons and importance of specific rules in terms of avoiding contamination. The control beliefs included in the survey provided unique information about the ways the workers thought about how they were or were not capable to produce clean and uncontaminated turkey products. Although these beliefs were difficult to assess, they might best lead us to understand hindrances to easy and effective performance of food safety behaviors. In our pilot study, workers were asked what factors and conditions were thought to facilitate or interfere with the workers doing what is needed to prevent contamination. Those factors that were more frequently mentioned as facilitating factors were the same “cleaning and keeping things clean” factors (i.e., use of sanitizing products, clean work garments, clean equipment) that workers felt they had control over. In the current study, workers did not perceive they had much control with regard to distractions, proper supervision, being too busy, being too tired, or knowing the rules, and these were the same factors mentioned more frequently as interfering conditions in the pilot interviews. As mentioned earlier, these may be the same factors that reduce perceptions of behavioral control in other work settings in which production occurs on a line and the pace of work is determined by the speed of the line. The normative beliefs assessed in this study are not surprising in terms of the referents considered. However, the overall normative belief scores were not consistent with the frequency that these referent groups were mentioned in our pilot study. In the pilot study, the most frequently mentioned group was supervisors, closely followed by co-workers, management, and government inspectors. In the current study, co-workers had the lowest score with respect to their motivation to comply. Perhaps this is not surprising considering that co-workers have much less influence over the workers’ behavior. Thus, from a practical perspective, managers of food safety in processing plants may want to emphasize the role of government inspectors and the consumers who will ingest the products. In this study we investigated and observed the impact of gender on the beliefs underlying food safety behaviors. Consistent with the stereotype, women generally had a more positive attitude toward engaging in food safety behaviors. Also consistent with the theory of planned behavior, when the behavioral beliefs associated with the attitude were included as a mediator of the effect of gender on attitude toward behavior, the gender effect nearly disappeared. The theory of planned behavior proposes that background factors such as gender have their influence on behavior through the associated beliefs that these individuals have regarding the behavior. Importantly, background factors are some of the ways that organizations can anticipate differences in behavior associated with characteristics of their workers. Gender is just one of the background variables that might be examined for understanding behavior in organizations. Importantly, gender is one individual difference that appears in most work settings in western societies. Although there is much consideration of the role of gender in work settings (Padavic & Reskin, 2002), much of this work focuses on gender as a surface variable. By placing the focus on beliefs as the elementary determinants of behavior, the theory of planned behavior provides a means to consider the deeper, psychological influences of how gender will influence behavior in organizations (cf. Jackson et al., 1995). In this fashion, research illuminates how an important and prevalent surface individual difference variable such as gender has its impact on behavior in organizations through the deeper psychological processes articulated in the theory of planned behavior. One limitation of the present study was the unavailability of any observed behavior or outcome data. Because workers came from several different departments in the plant, it was not possible to measure any specific observable behaviors common to all workers. Armitage and Conner (2001) report that TPB studies commonly measure behavior through self-report, but that self-reports of behavior are seen as less reliable and subject to self-presentational biases. Future work site studies using the TPB would have greater predictive validity if accurate measures of actual behaviors were available. The study was also limited to data from employees at one food processing plant. The strong climate of food safety in this specific plant could be one reason for a potential ceiling effect with regard to the relatively high scores on most of the TPB variables. On the positive side, these employees were quite diverse in terms of gender, race or ethnicity, and national origin (e.g., Mexico, South Africa, Vietnam, China, the Philippines). We went to considerable time, effort, and costs to recognize this diversity by providing a Spanish version of the survey to Spanish speaking employees with limited English reading skills. Food safety is a challenge that must be investigated from multiple perspectives and levels of analyses. Keeping food safe and avoiding contamination result from a number of factors beginning with preventive work at the farm, at food processing sites, and ending with the behavior of the consumer. This “Farm to Table” approach to food safety is seen as the most effective way to prevent foodborne illnesses (Sperber, 2005). This paper shows how psychological approaches at the processing stage can contribute to keeping food safe and avoiding contamination (cf. Foster & Kaferstein, 1985; Schafer et al., 1993). In particular, this study demonstrates the potential for using the theory of planned behavior for understanding food safety and security behavior in a work setting. The study also suggests that attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and behavior intention can play important roles in understanding how to prevent foodborne diseases in the future. Food processing is a major industry that has an impact on the organizations and their members engaged in food processing as well as the clients and customers served the food. In addition to the production of the food, these organizations have to be very concerned about the quality in the way the food is produced and processed so that is safe for the ultimate consumers. As noted earlier, organizational viability, worker employment, and customer health are very important consequences resulting from the manner in which the food is produced. This study demonstrates that the issue of the motivation of the workers to engage in safe food production behaviors can be well understood and explained by considering the theory of planned behavior. Given the ability of the theory of planned behavior for explaining the food safety behavior of production workers at this food processing plant, it is reasonable to consider the TPB for helping researchers understand and predict workers’ safety behaviors in other organizational settings. The TPB has been shown to be applicable for understanding a variety of behaviors outside the organization realm. Perhaps it is now time to bring the theory more broadly into the study of behavior inside organizations. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Note 1 We choose to use gender to indicate the sex-related factor involved in these food safety workers because the articipants in this study self-declared their gender, and some chose not to self-report. We did not observe and record a categorization of the respondent’s apparent biological sex. Consequently, we chose to label the response as gender rather than sex. Acknowledgements We appreciate the advice of Wendy Troop-Gordon on the path analyses as well as the comments of reviewers to earlier drafts of the manuscript. Cite this article as: Nickell, G. S. & Hinsz, V. B. (2023). Applying the theory of planned behavior to understand workers’ production of safe food. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 39(2), 89-100. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2023a10 Funding: This research was supported by a grant by the USDA Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service awarded to the second author. A portion of this research was presented at a meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Chicago. References |

Cite this article as: Nickell, G. S. & Hinsz, V. B. (2023). Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand WorkersŌĆÖ Production of Safe Food. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 39(2), 89 - 100. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2023a10

Correspondence: Verlin.Hinsz@NDSU.edu (V. B. Hinsz).

Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS