Could Positive Political Skills Work to the Benefit of Work Performance? Is it Possible?

[ÂżPodrĂan las destrezas polĂticas positivas obrar en beneficio del rendimiento laboral? ÂżEs posible?]

Aharon Tziner1, 2, 3, Amos Drory1, and Abira Reizer4

1School of Business Admin &OD, Peres Academic College, Israel; 2Tel-Hai College, Israel; 3Netanya Academic College, Israel; 4Ariel University, Israel

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2024a8

Received 15 April 2024, Accepted 7 July 2024

Abstract

The outcomes of Organizational Politics (OP) on employee attitudes and behaviors in the workplace have been widely researched in recent decades. Whereas many findings demonstrate detrimental effects on employees and organizations, other studies identify positive outcomes. This research aimed to probe the association between the perception of positive politics in the organization, reflected in the positive political skills of one’s superior, and the perception of individual and organizational performance. The study empirically examined a theoretical model targeted to enlarge the network of constructs, leading to a more profound understanding of the role of positive political behavior in individual and organizational performance. Two independent samples – employees (n = 318) and managers (n = 297) – were applied and yielded similar results. Both samples indicated that the perception of the superior as an effective political player was significantly associated with the perception of both individual and organizational performance. In addition, both samples signaled that leader–member exchange (LMX) mediates the associations between supervisor use of OP and performance evaluations. Finally, the superior’s Dark Triad characteristics moderated the mediation path of LMX in the association between OP and individual performance. However, the moderating effect of Dark Triad in the mediating role of LMX in the link between superior use of OP and organization performance was non-significant. These findings provide a strong case for further research into the positive role of OP and the potential moderators and mediations in this process.

Resumen

El efecto de la política organizativa (PO) en las actitudes y comportamientos laborales se ha estudiado lo suficientemente en los decenios recientes. Mientras muchos resultados muestran efectos perjudiciales en empleados y organizaciones, otros presentan resultados positivos. Este estudio se propuso demostrar la asociación entre la percepción de la política positiva en las empresas, cómo se refleja en las destrezas políticas positivas del superior, y la percepción del rendimiento individual y organizativo. El trabajo analiza empíricamente un modelo teórico dirigido a ampliar la red de constructos para llegar a una comprensión más profunda del papel del comportamiento político positivo en el rendimiento individual y organizativo. Se utilizaron dos muestras independientes (empleados, n = 318 y directivos, n = 297), que arrojaron resultados similares. Ambas muestras indicaban que la percepción del superior como jugador político eficaz se asociaba de modo significativo con la percepción del rendimiento individual y organizativo. Además, las dos muestras indicaban que el intercambio jefe-subordinado (LMX) mediatiza las asociaciones entre el uso de la PO por parte del superior y la evaluación del rendimiento. Por último, las características de la “tríada oscura” del superior moderaban la vía de mediación del LMX en la asociación entre la PO y el rendimiento individual. No obstante, el efecto moderador de la “tríada oscura” en el efecto mediador del LMX en el nexo entre el uso del superior de la PO y el rendimiento de la empresa no era significativo. Los resultados avalan firmemente la necesidad de seguir investigando en el papel positivo que juega la PO y los moderadores y mediaciones potenciales en este proceso.

Palabras clave

PolĂtica organizativa (PO), TrĂada oscura, LMX, Rendimiento, ModeraciĂłn moderadaKeywords

Organizational politics, Dark triad, LMX, Performance, Moderated moderationCite this article as: Tziner, A., Drory, A., & Reizer, A. (2024). Could Positive Political Skills Work to the Benefit of Work Performance? Is it Possible?. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 40(2), 89 - 102. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2024a8

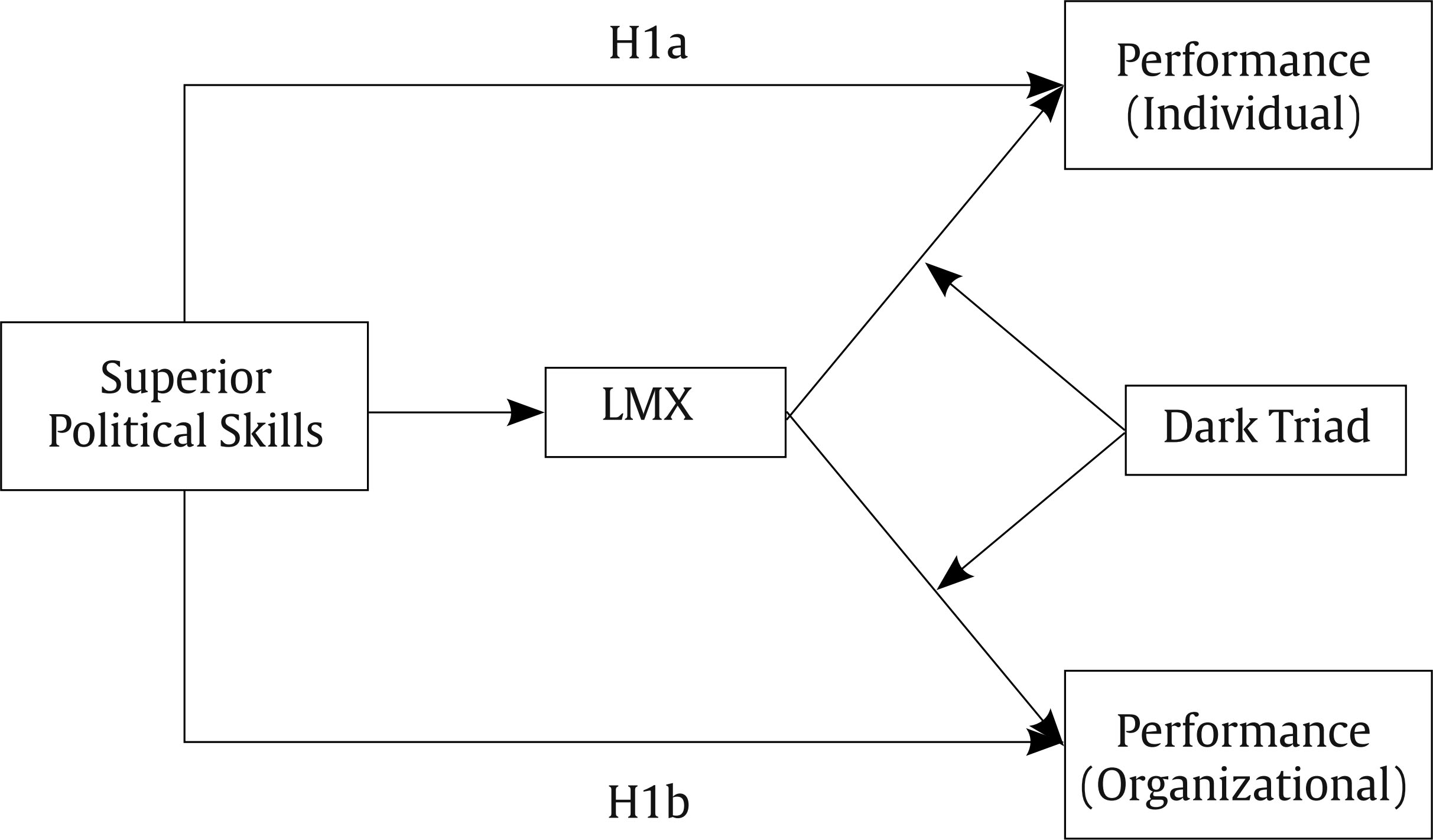

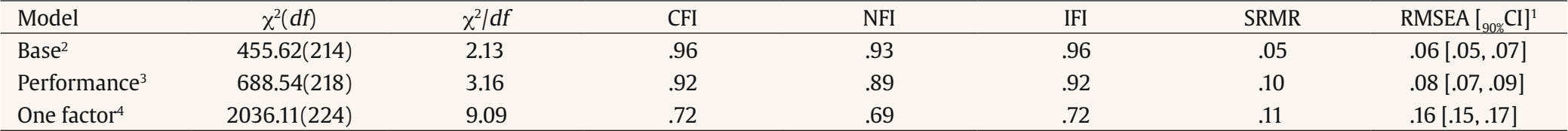

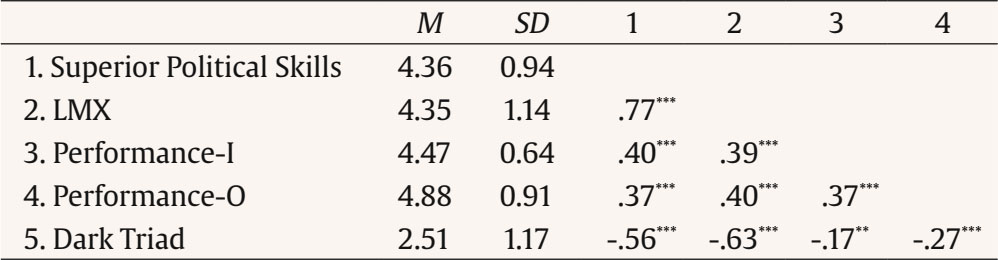

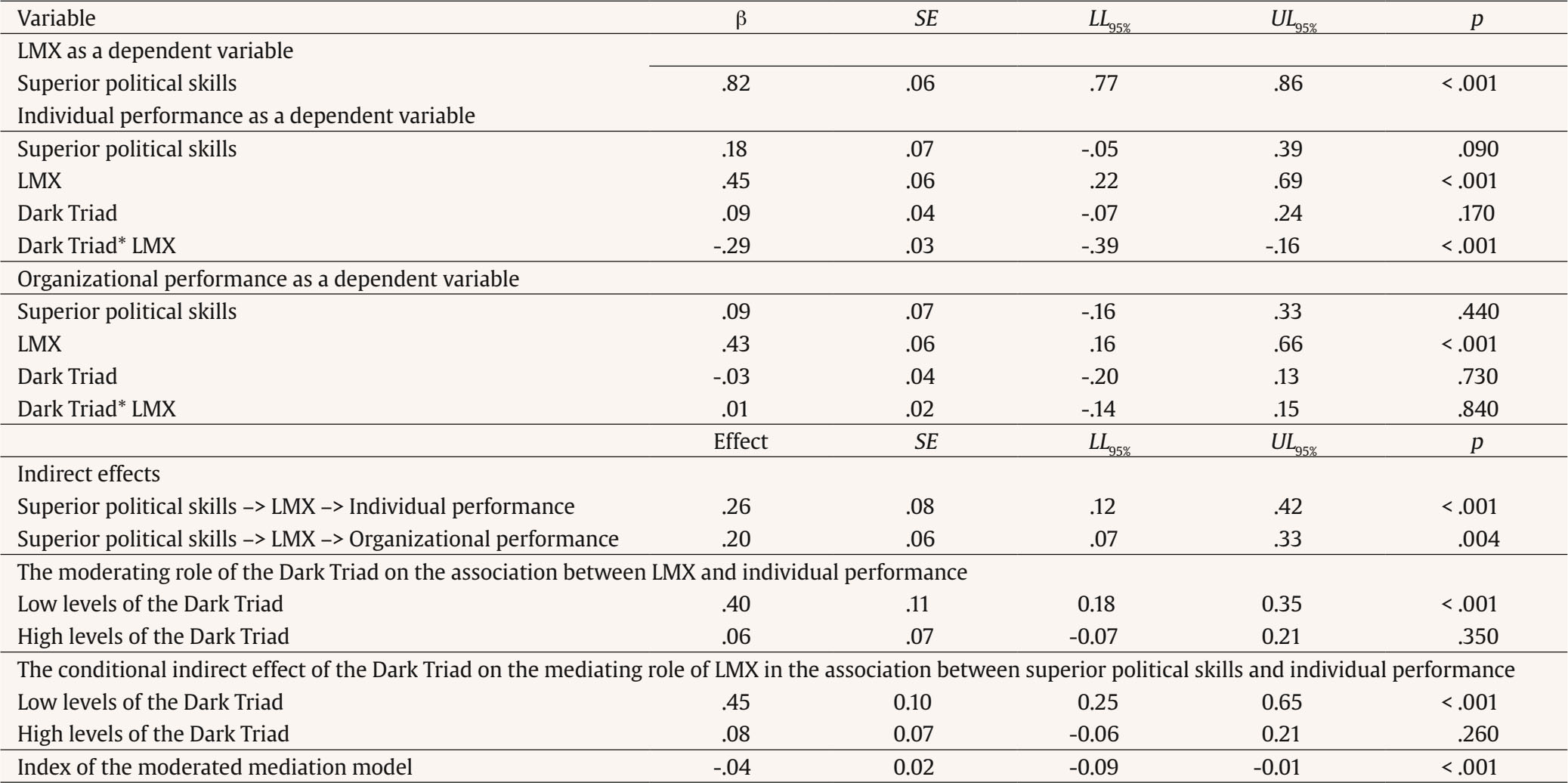

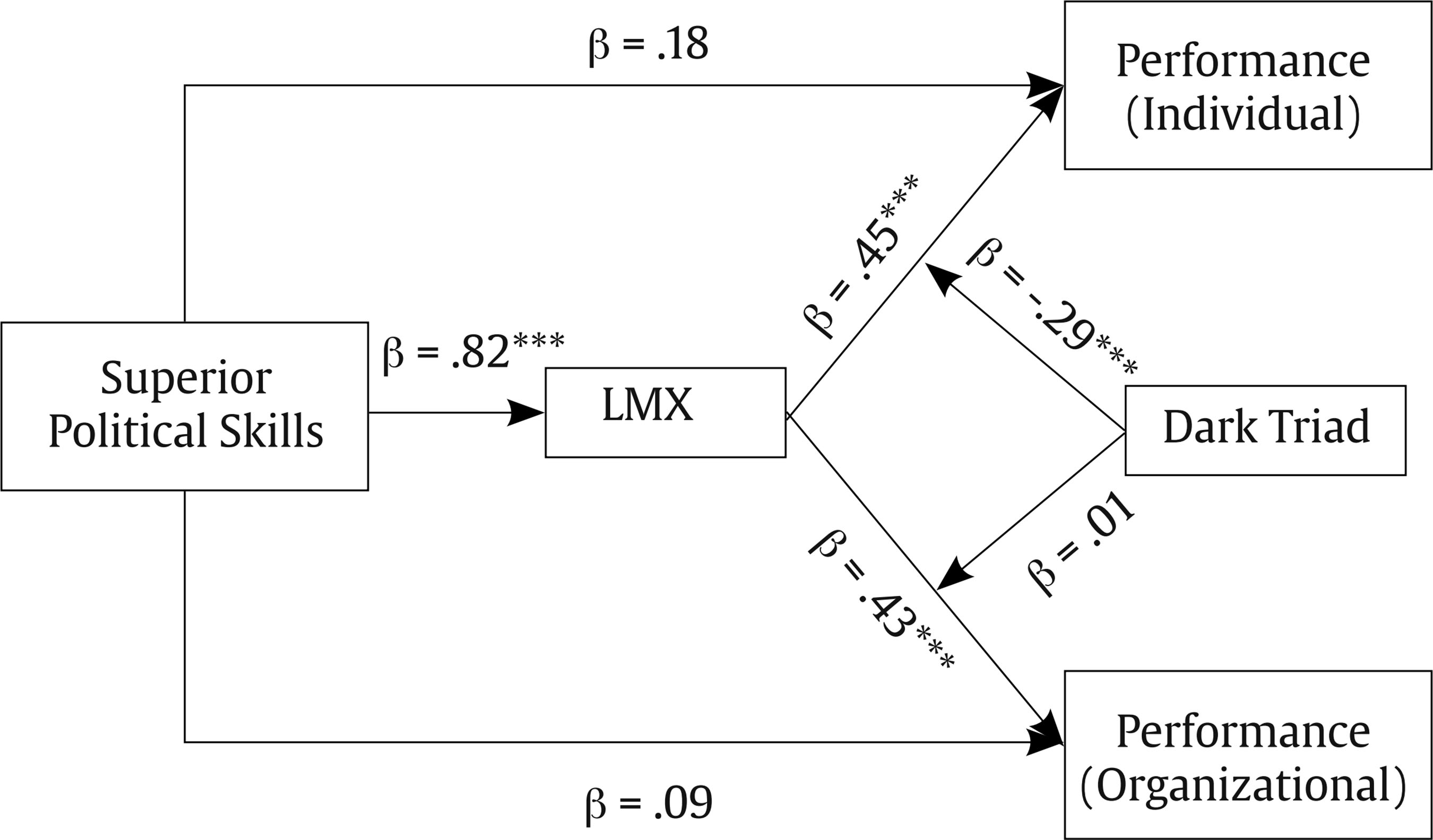

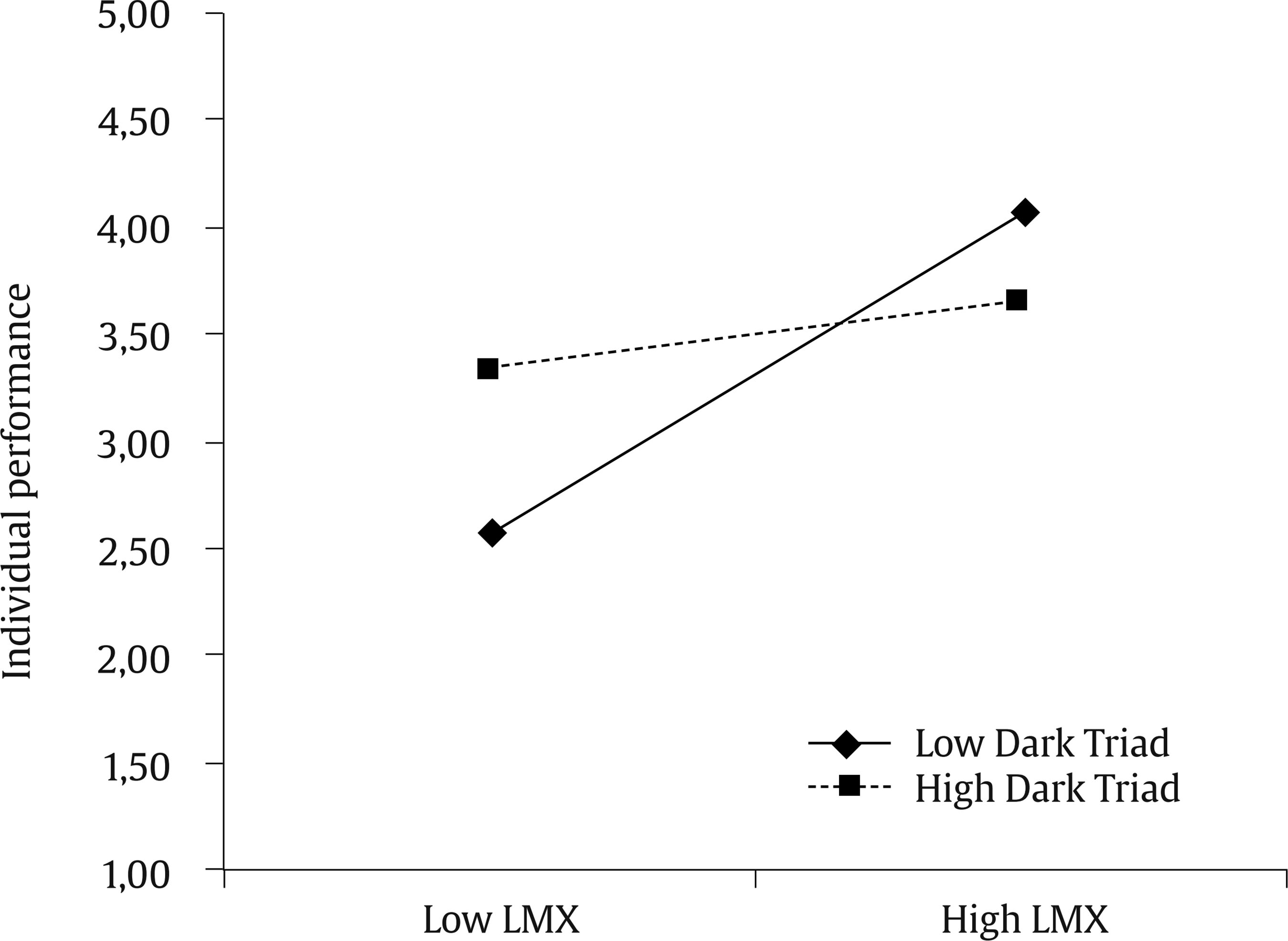

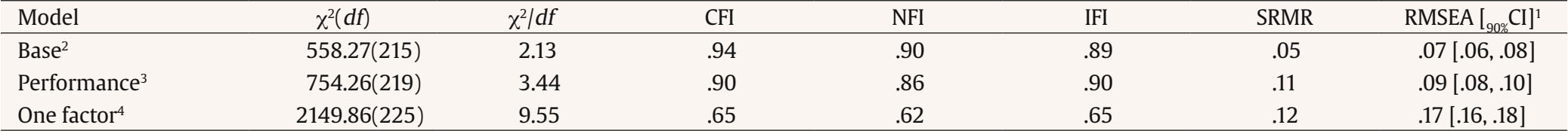

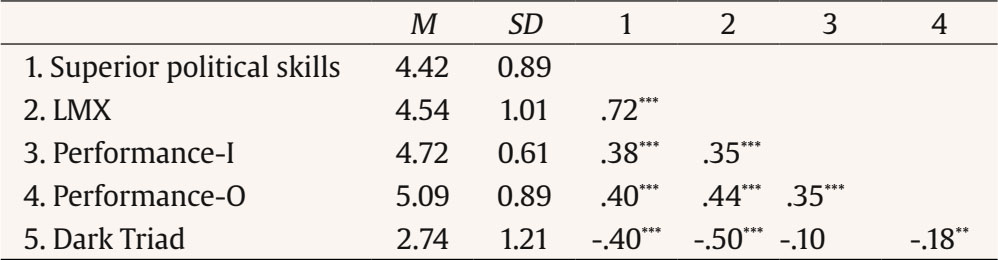

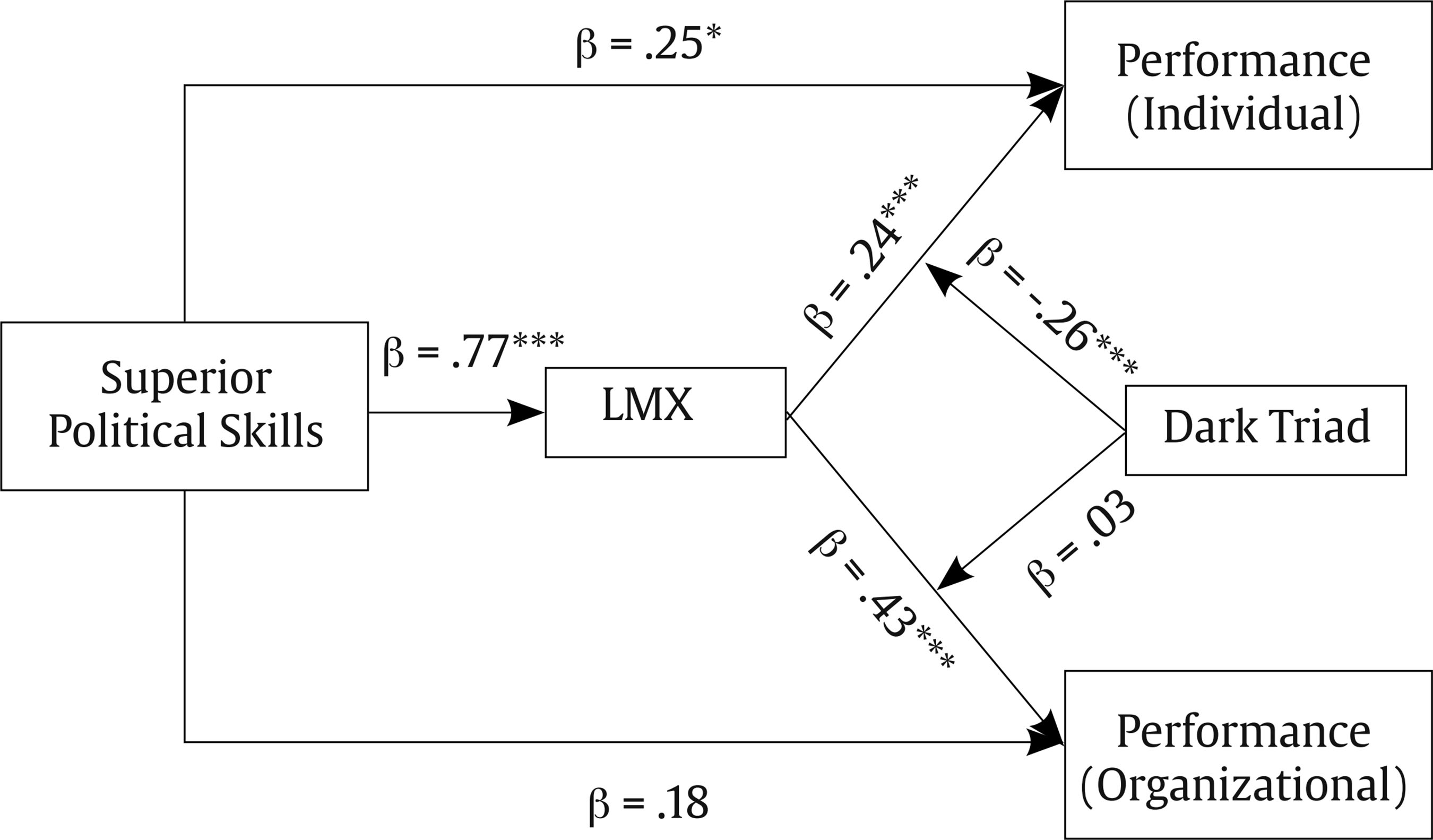

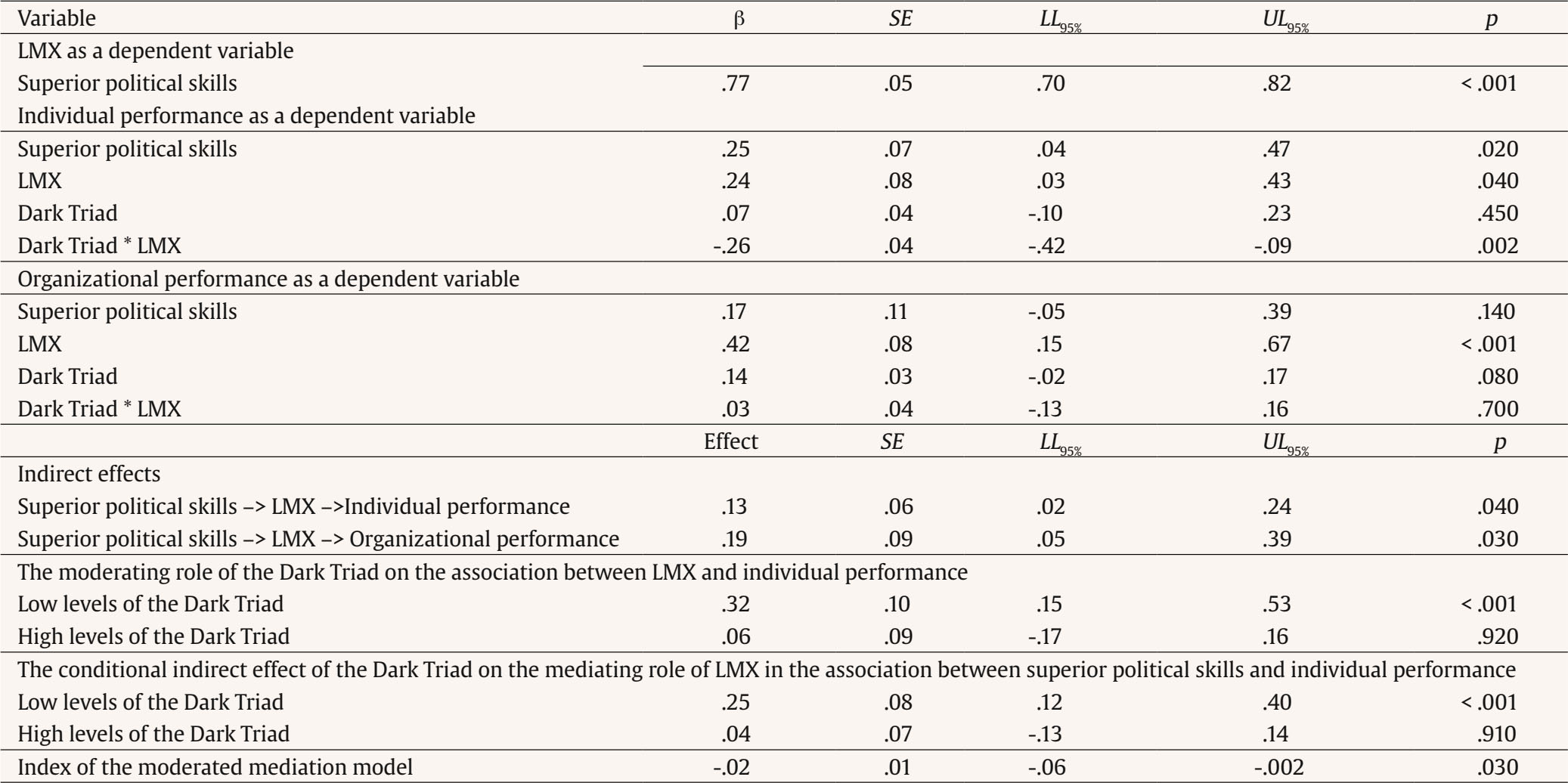

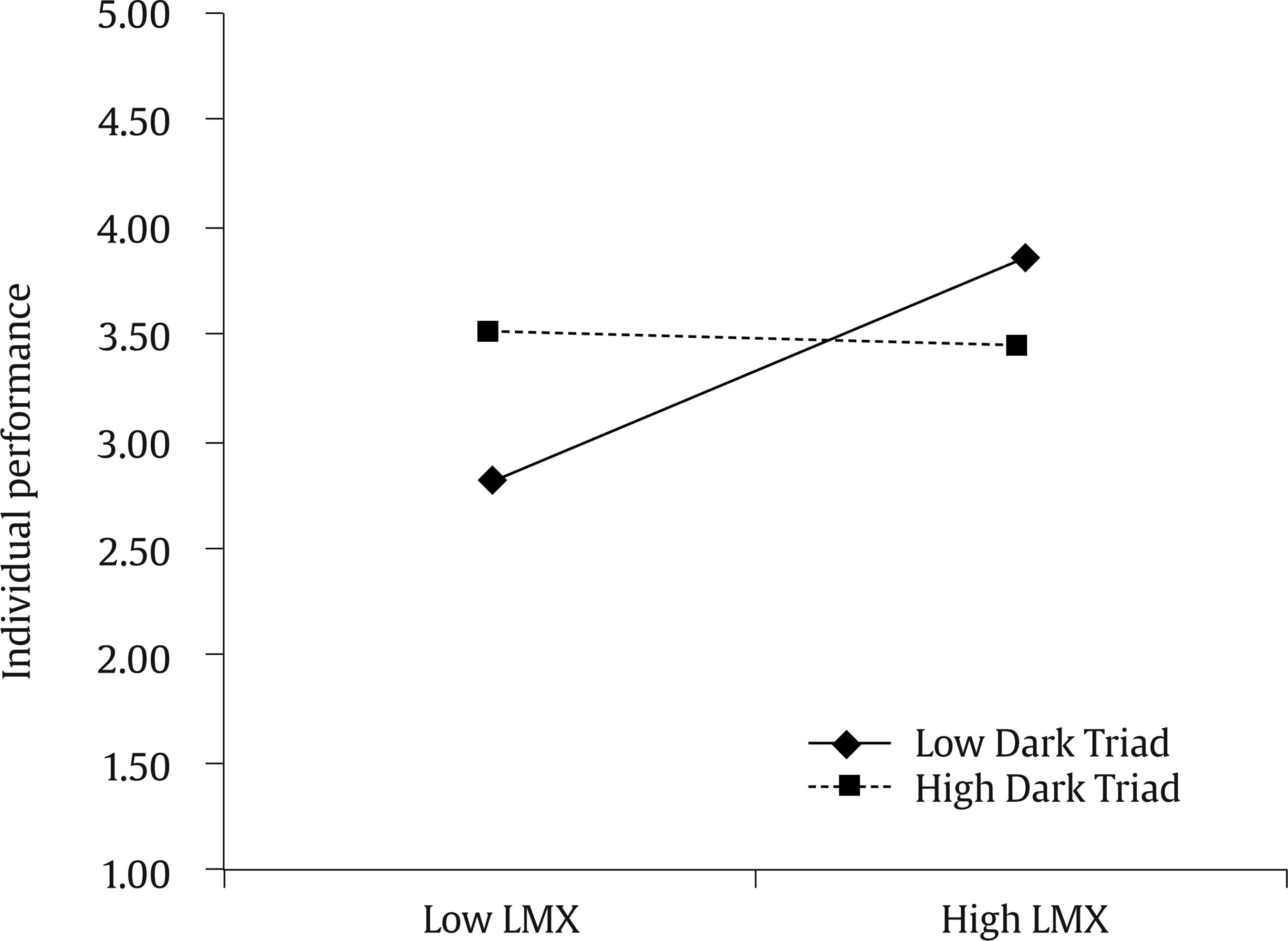

Correspondence: atziner@netanya.ac.il (A. Tziner).The objectives of the present research are to empirically examine the effect of the positive political image of the superior on organizational and individual performance and to explore the moderating and intervening roles of particular aspects of the superior’s characteristics and the superior-subordinate relations. The abundant literature on Organizational Politics (OP) in organizational behavior journals over the last few decades has given rise to what one might best describe as an ongoing debate on the effects of OP on employee attitudes and behavior in the workplace and the organization (see Ferris et al., 2019). On the surface, the conclusions drawn are mixed. On the one hand, many findings traditionally demonstrated adverse outcomes for employees and harmful consequences for the organization (e.g., Hochwarter, 2012; Vigoda-Gadot, 2000) and, on the other hand, positive outcomes have been discerned emerging from OP (e.g., Buchanan & Badham, 2008; Gotsis & Kortezi, 2011, cited in Soares, 2018). Much depends, of course, on the “desired outcome.” Thus, for example, Maes and Van Hootegem (2022), citing Frost and Egri (1991), perceive OP as a negative propensity by which “power bases are built up through the maneuvering of structures, values, and symbols that shape reality so that the sought changes are regarded as legitimate, desirable, and inevitable” (p. 8). However, Parmentier and Reynaud (2022), for example, suggested that while structural change (a source of much political scheming) could lead to an environment replete with vying outlooks and concerns, the political behavior could, nevertheless, cast a calming effect on the actual behavior. At the outset of this paper, it is important to stress the implications arising from OP in the workplace. For example, Cesinger et al. (2023) remind us that senior managers set the company’s mission, organizational strategy, and culture among their other multifarious tasks and, consequently, their commitment to the organization and their personality attributes (reflected in their communication with colleagues and subordinates) are critical to the efficient functioning of the business concern. Indeed, they affirm, following Hambrick (2007), that organizations reflect the attributes of the senior managers so much so that their dispositions, values, and behaviors account for between five to twenty percent of the variance in the firm’s fortunes (Crossland & Hambrick, 2007), consequently serving as a key predictor of the company’s performance (Palmer et al., 2017). The importance of this discussion cannot be understated. Following Bodla and Danish (2009), organizational politics influences every decision within the organization, including those associated with establishing business ethics and support networks and efficiency throughout the company, the neglect of which can lead to the organization’s total demise. To drive this point home, Diller et al. (2021) stressed that prominent and charismatic heads of companies, often described as dark personalities, were also labeled as having narcissistic or psychopathic tendencies (Ashcroft, 2016; Isaacson, 2011), features to which we return in this paper. For instance, companies that dissolved on account of dark organizational politics (among other issues such as fraud) include Enron, WorldCom, and Tyco International (Barkow, 2008), while notorious scandals were associated with the Lehman Brothers and WorldCom (Jonason et al., 2015). We begin our journey with a brief review of the definitions of OP, if but to recall the complexity of doing so and the magnitude of the issue since the subject has been widely reviewed in the literature. To begin, however, we cite Gandz and Murray’s (1980) assertion that ninety percent of their survey sample contested that organizational politics in the workplace was usual – a percentage that remained constant for thirty years. More recently, a survey of 1,500 employees from a variety of industries and sizes conducted by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) in 2022 unearthed that 76% of employees were caught up in organizational politics at some point in their working lives, and 55% of employees concurred that organizational politics impacted their ability to advance their careers (SHRM, 2022). One way or another, organizational politics appears to be a significant part of workplace life. In a relatively early discussion of the definition of OP based on a literature review, Drory and Romm (1990) concluded that key components in the definition of the term incorporate the following actions: (1) exerting influence, (2) employing tactics unendorsed by the organization, and (3) inducing conflict, whether direct or otherwise. Notably, the intentions behind the political behavior are not necessarily a component of the definition. The underlying assumption in all the definitions included in their review was that OP is detrimental to the organization and should be viewed negatively. Moreover, a more recent sampling of the definitions of OP (Landells & Albrecht, 2017) illustrates a diversity of approaches, most of which still shed a pessimistic light on the phenomenon whereby undesirable behaviors based on self-interest include further acts such as aggrandizement, betrayal of colleagues, and ingratiation (e.g., Allen et al., 1979; Chang et al., 2009; Rosen et al., 2009). Indeed, Landells and Albrecht (2017), citing Dipboye and Bigazzi Foster (2002), detected no fewer than fifteen definitions of organizational politics, ranging from social skill, unjust equality, and lying and dishonesty to the notion that OP is no less than belonging to a club. Furthermore, Abitbul et al. (2020) asserted that organizational politics includes self-serving behavior such as idea theft, scapegoating, masked tactics, and evil acts. By way of further examples, organizational politics has been described as:

Notably, these negatively oriented definitions indicate that beyond management, individuals in the organization take initiatives to pursue self- or group interests and those of the key movers in the organization. These actions promote adverse responses among colleagues, negatively affecting employees and the organization. Parmentier and Reynaud (2022) illustrated various trends or streams the definitions indicate. For example, for Elbanna (2018) OP incorporates power and influence that serve employees’ self-interests (see also Pfeffer, 1992). In that vein, Gandz and Murray (1980, p. 239) and Geppert et al. (2016) focused on the centrality of power in organizational politics and, particularly, how power interfaces with decision-making in the organization. An interesting offshoot of this approach is that of Pfeffer and Salancik (1974), who give weight to the bargaining power of the players in the organization and how they use political machinations to allocate resources. In contrast, rather than highlighting the “decision-makers,” Eldor (2017, p. 236) (cited in Parmentier & Renaud, 2022) spotlights employees who manipulate power to achieve objectives that do not necessarily align with the organization’s goals. In this paper, two comments are necessary regarding the distinction between negative and positive OP. First, self-serving behavior does not necessarily contradict the organization’s interests. It is quite acceptable for an employee or an executive to attempt to promote their interests by acting effectively on behalf of the organization. For example, employees may work hard and serve the organization even when their main objective is to get promoted. Consequently, self-serving behavior per se should not define organizational politics. Indeed, at the heart of OP, self-interest does not necessarily have to take on a negative nuance. For instance, Gotsis and Kortezi (2011) (cited in Soares, 2018), posited that, from an ethical standpoint, “self-interest can be enlightened and ‘bounded,’ fostering constructive politics within organizations as a constructive and emancipatory process characterized by participation and interactivity” (p. 505). This stance reflects a view expounded by Gotsis and Kortezi (2011, p. 458) (cited in Soares, 2018) that OP can be characterized by “pro-social dispositions, intrinsic motivation, acting in conformity to social norms, a focus on ethics, and other regarding/self-regarding preferences.” Second, using power tactics similarly does not necessarily differentiate between positive or negative OP. Organization leaders routinely use power tactics to promote desirable organizational goals. A proficient leader, for example, should be able to exert power on resentful employees or interest groups, and prevent the attainment of their deleterious desirable outcomes based on selfish interests. We now move to descriptions of OP that go beyond negative associations. Although the definitions cited primarily highlight the negative aspects of OP, studies in the last two decades have given mixed results, leading to conclusions that there are both negative and positive facets of organizational politics (Buchanan & Badham, 1999, 2016; Fedor et al., 2008; SHRM, 2022). For example, Buchanan and Badham (2016) indicated that political behavior generates functional and dysfunctional outcomes for the individual and the organization. Alternatively, consider that while Bedi and Schat (2013) asserted that organizational politics negatively affects the level of employees’ motivation, Rughoobur-Seetah (2022) found a reverse phenomenon among workers surveyed in Mauritius, ascribing the unexpected results to a high work commitment that spurred employees to work even harder to contain any adverse effects that OP impinged on them. Kapoutsis (2016) viewed organizational politics as “managing meaning.” In that sense, Kapoutsis saw political behavior as one of several premeditated acts that include, for example, influential tactics that enhance one’s self-presentation, impress management, and manage situations in the organization that produce desired outcomes “that would otherwise be unfeasible” (Kapoutsis, 2016, p. 41). Nor are individual researchers necessarily bought into one or the other side of the debate. For instance, even though a study by Eliyahu et al. (2021) highlighted the negative impact of OP on the subjects investigated, they nevertheless asserted that one cannot overlook OP’s favorable aspects and the possibilities it advances for employees and the organization. Along with Rosen (2006), Eliyahu et al. (2021) recognized that organizational politics is indicative of a dynamic organization that has the potential to engage its staff in the processes and decisions undertaken by the organization. Indeed, a recent paper by Faiz et al. (2022) illustrates the two-fold nature of OP, their study of perceptions of organizational politics (POP) revealing its effects on career advancement and moral disengagement. Specifically, the investigation pinpointed how social networks mediate career achievement, and how social undermining operates between POP and moral disengagement (see also Barsky, A., 2006; Chen et al., 2022). Indeed, POP relates highly to increasing one’s social networks because employees garner satisfaction from the associations between these elements in their workplace experience, nurturing a subjective sense of success in the organization. In that vein, and in a quest to find in favor of positive organizational politics, we might better concur with Fedor et al. (2008), who posited, categorically, that POP represents two separate perceptions, namely (1) negative politics and (2) positive politics, both categories applying to the individual, group, and organization. Furthermore, Fedor et al.’s (2008, p. 76) investigation affirmed that perceptions of positive politics play a role in organizational life “significantly beyond perceptions of negative politics.” The authors posit, somewhat in line with Faiz et al. (2022, p. 639), that “our findings reveal that POP generates not only negative attitudes and behaviors but also positive outcomes”. “In other words, advantageous political activities and undesirable political behaviors are distinct." Indeed, one can posit that organizational politics is not only about manipulating or deceiving others; rather, it can be construed as employing political skills to achieve common goals and a culture of positive political engagement. For example, positive teams can flourish in such an environment, conflicts can be resolved more easily, and cooperation and innovation can be promoted. As indicated above, on the individual level, when positive interpersonal relationships are achieved, individuals are more likely to experience greater job satisfaction. Consequently, the employees gain increased opportunities to influence and, among other things, opportunities for their advancement. In view of the history of OP theory and research, and considering the differing perspectives regarding the negative vs. positive role of this phenomenon, we would like to offer an objective working definition, which avoids value judgement and speculation about intent but rather focuses on the nature of the behavior itself. According to this definition, OP pertains to informal behavior consisting of applying persuasive and influential tactics aimed at affecting the impressions, attitudes, and behavior of others at work. The organizational consequences of political behavior may be desirable or undesirable to the organization. Buchanan (2016, p. 363) noted that a review of the research literature indicated a more balanced approach whereby the perceptions of politics shifted over time from negative to positive, with an expanded interest in how an organization’s members experience political behavior and utilize political skills. Notably, the construct of political skills was introduced in the last decades as a vital competency in organizations, necessary for effective management (Ahearn et al., 2004). In general, this concept encompasses strategies that leverage constructive political behaviors to enhance organizational effectiveness and achieve desired outcomes. These tactics focus on building alliances, fostering collaboration, and promoting collective goals rather than engaging in manipulative or self-serving behaviors. Several key characteristics of positive political tactics are often discussed. Brass et al. (2004) refer to it in terms of cultivating relationships and networks based on trust and reciprocity that can facilitate information sharing, resource allocation, and problem-solving within organizations. Other researchers point at collaborative decision-making, namely involving diverse stakeholders in decision-making processes (Hernandez et al., 2014), transparent communication (Kaplan & Norton, 2008), and aligning individual and team goals with organizational objectives (Locke & Latham, 2002). Operationally, the common definition of the construct focusses on individuals’ skills and capabilities to understand colleagues in the workplace and to maximize that comprehension to influence others to act in ways that promote personal objectives or those of the organization (Ahearn et al., 2004, p. 311). Although a wide consensus has not yet been achieved on the definition of political skill, most recent studies rely on the definition that describes it as ‘the ability to effectively understand others at work, and to use such knowledge to influence others to act in ways that enhance one’s personal and/or organizational objectives. Ferris et al. (2005) suggested that political skill has been considered to consist of four dimensions: social astuteness, interpersonal influence, networking ability, and apparent sincerity. The concept of political skill has become more significant as increasing research is directed toward it. Bing et al. (2011), in a literature review, looked at the link between political skill and job performance, and although this review included a limited number of studies, it confirmed that political skill positively affects how employees perform in their work environment. Harris et al. (2007) showed that individuals who used high levels of any of the tactics, and who were politically skilled, achieved more desirable supervisor ratings than did those who used the tactics but were not politically skilled. Opposite results were found when impression management usage was low. That is, individuals who were not politically skilled created a more desirable image in their supervisors’ eyes than did their politically skilled counterparts when they did not use these tactics. Chen et al. (2022), through meta-analysis, examined the effects of political skills on career success and the moderating factors between them. This study finds that political skills have the strongest promoting effect on one’s sense of achievement in subjective career success and have the weakest promoting effect on economic returns in objective career success. Kimura (2015), in his review, critically examined previous empirical studies in light of this theoretical background and pointed out that, although previous empirical studies supported the theoretically assumed effects of political skills, they failed to confirm how and why these skills brought about these effects. Based on this examination, the author suggested the examination of mediators and dimensional differences derived from theory that could lead to more effective exploration of the impact of political skill. Other studies have indeed attempted to look at mediating variables in this context. For example, Saleem et al. in press) found that political skill is a significant predictor of employee job performance, career development and entrepreneurial intentions. Moreover, the mediating role of personal reputation was confirmed for the proposed relationships. Tripathi et al. (2023) found a significant three-way interaction between POP, conscientiousness, and political skill in predicting OCB. The presence of high conscientiousness and high political skill alleviates the negative effect of politics on OCB. The purpose of this investigation was to probe the association between the perception of positive politics in the organization, as reflected in the positive political skills of one’s superior, and the perception of individual and organizational performance. We hypothesized a positive association between the above variables. Specifically, we hypothesized that: H1a: The superior’s use of political skills is positively associated with individual performance. H1b: The superior’s use of political skills is positively associated with organizational performance. However, the literature strongly indicates that the link between political skill and performance is not necessarily straightforward. It is potentially mediated and moderated by other variables. For example, Munyon et al.’s (2015) meta-analysis review of the literature demonstrates that political skills are a tool that can be employed to promote both positive and negative objectives, whereby the direction in which those tactics go is a function of various factors at play in any given situation. In this study, we examine two such variables. We hypothesized that leader-member exchange (LMX) mediates the relationship between the perception of superior political skills and performance, and that the negative personality characteristics of the superior (the Dark Triad) moderate the relationship between LMX and perceived performance. The main argument underlying the theory of LMX stresses that for each of their employees, managers tend to develop different styles of management/leadership in what is described as a dyadic approach (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). The dynamics between managers and their subordinates, including the quality of the relationship and the chosen management style, will influence subordinates’ responses and work attitudes, including their performance behaviors (Ilies et al., 2007). Building on the idea of “give and take” from social psychology (reciprocity theory; Gouldner, 1960), the measure of the relationship between employees and their supervisors (high or low LMX) impacts how the employee responds. Employees with productive relationships with their managers (high LMX) tend toward more positive attitudes towards them. They are more inclined to return the favor by putting in extra effort in ways akin to those described by Equity Theory (Adams, 1965). Conversely, employees with a strained relationship with their managers (low LMX) might be less likely to reciprocate, potentially leading to reduced commitment and lower performance. Thus, following Adams (1965), the levels of LMX result in higher or lower degrees of respect, commitment, and mutual trust that naturally have consequences for job performance. Employees with solid relationships with their managers (high LMX) tend to get more rewards than those with weaker relationships (low LMX). These rewards/benefits can be both official and unofficial, including tangible benefits (e.g., salary increases, bonuses, or other financial rewards), career opportunities (e.g., recommendations for promotions, training programs, or special projects), and a supportive environment (e.g., more emotional encouragement and positive feedback from the supervisor) (for further reading, see Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995; Zagenczyk et al., 2015). Consequently, employees high on LMX are more prone toward constructive behaviors, while those low on LMX toward adverse behaviors (Breevaart et al., 2015; Tziner et al., 2012). Indeed – within the context of teasing out the nature and dynamics of negative LMX behaviors with which we are concerned in this paper, and in tandem to enlarge the network of constructs to explain the adverse effects of LMX – it is essential to record that weak relations between employees and supervisors will almost certainly end up in mutually-based counterproductive behavior (Chernyak-Hai & Tziner, 2014). In the literature, studies of LMX as a potential mediator of misconduct at work have stressed contextual-level and job-level predictors (e.g., He et al., 2017; Sharif & Scandura, 2017). However, with one or two exceptions (e.g., He et al., 2017), studies of the effects of “specific” attributes of “negative” LMX job performance at the individual and organizational levels are scarce (e.g., He et al., 2017). In this study, we hypothesized that LMX mediates the association between the perception of superior positive political skills and perceived performance. When the subordinate-superior relations are strong in terms of mutual understanding and trust (high LMX), the superior’s political skills are expected to be more effective in encouraging the employee to reach a higher level of individual and organizational performance. When LMX is low, the superior’s political skills will be less effective in encouraging performance. H2a: LMX mediates the association between the superior’s political skills and individual performance. H2b: LMX mediates the association between the superior’s political skills and organizational performance. Taking this proposition one step further, it is sanguine to note several personality traits found among managers – narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy – that, from a theoretical perspective, share a common negative thread. So much so that Paulhus and Williams (2002) clustered the traits under a unifying concept, the Dark Triad (DT). The researchers contend that these traits interrelate to such an extent that they can be considered a single mega-trait, although, in essence, they do not fully overlap. “Narcissists” have been described as possessing a highly inflated but vulnerable self-image. “They seek attention, social approval, respect, and admiration, consistently striving to reaffirm their grandiose self-views” (Szabó et al., 2023, p. 1). While this attribute can motivate narcissists to strive for higher performance standards at the individual and organizational levels, narcissism may lead to distrust of colleagues, such that anger and vindictiveness arise when they are not sufficiently appraised or admired by people around them. This perceived lack of attention further instigates unethical behaviors and even bullying. In contrast, the behavior of individuals scoring high on “Machiavellianism” is fueled by their motivation to gain power and control over others using manipulative means while disregarding ethical concerns (Bereczei, 2018). Szabó et al. (2023) observed that people high on “psychopathy” are likely to act impulsively with uninhibited hostility (Vize et al., 2018); they gain satisfaction by offending and are more likely than Machiavellians to employ abuse and hostility in their interpersonal communications. Of interest, however, Drory and Gluskinos (1980) found that high Machiavellians were more flexible in adapting their leadership style to situational changes but, not surprisingly, they tended to be authoritative, barking orders and, concomitantly, less likely to reduce tension in group task-oriented scenarios. Notably, the Self-affirmation theory can explain the behaviors subsumed by this mega-trait (Cohen & Sherman, 2014). This theory postulates that individuals conduct themselves in ways that magnify their self-aggrandized views. When attaining high-standing positions and status in the organization – regardless of the means employed – proves to be a valuable and influential asset, “Dark Triad” individuals will likely pursue further moves to exert even more control and power. The Negative Attributes of the Dark Triad O’Boyle et al. (2012) observed that each of the three traits described above contains a degree of malevolency, directly affecting interpersonal behavior. As anticipated, the Dark Triad as a composite attribute has been shown in numerous studies to lead to undesirable antisocial outcomes and interpersonal noxious behaviors, such as self-centered, abusive behavior and exploitation of others (Jonason & Webster, 2010; Sijtsema et al., 2019), and belligerent behavior (Zhu & Jin, 2021). Diller et al. (2021) observed that executives in higher positions are more likely to display Dark Triad attributes than other lower-level management. The latter leaders have a negative influence on their (immediate) teams (Van Dijk & De Cremer 2006), while the higher managers affect the entire company (Farrell & Whidbee, 2003). Thus, as indicated above, Diller et al. (2021) exhort that company heads can destroy an organization as a whole by taking risks and employing strategies that include bullying and manipulation, as well as fraudulent acts and financial misinformation (e.g., Cragun et al., 2020). Not surprisingly, Lainidi et al. (2023) noted that Dark Triad abusive leadership was associated with increased subordinate turnover and reduced job satisfaction. In one of the rare meta-analytical studies of the Dark Triad, O’Boyle et al. (2012) mined associations among DT traits and work behaviors from 245 independent samples of original reports published between 1951 and 2011 (N = 43,907) searching for implications for job performance and counterproductive work behavior (CWB). The results indicated that CWB was moderately related to upsurges in all three components of the DT. However, Machiavellianism and psychopathy – but not narcissism – accounted for reductions in the quality of job performance. These relationships were moderated by contextual features such as culture and authority. Moreover, we might contend that the narcissism measure was more attuned to the agentic aspect of that attribute than its antagonistic aspect (see Szabó et al., 2023 for a further discussion of the two aspects of narcissism). The literature on DT appears not to have reached a definite conclusion about whether the Dark Triad operates on a composite level or as three distinct character traits that each, in its way, contributes to specific workplace outcomes. The differences between the three constructs are well-reviewed by Diller et al. (2021) but go beyond the scope of this paper. For O’Boyle et al. (2012), the DT’s three traits are positively related but are distinctive enough to assure segregation at both the theoretical and empirical levels. This notion is backed up by Szabó et al. (2023), who posited that DT traits overlapped but were, nevertheless, discrete constructs that varied in the source of their underlying motivations, degree of impulsivity, and the identity needs of the individual, even to the point of differentiating between the agentic aspects of narcissism and its antagonistic aspects (after Truhan et al., 2021). Conversely, Diller et al. (2021), while affirming that the Dark Triad traits were distinct constructs, cited several sources indicating that the traits overlapped in several areas, including impaired social and moral emotions, egotistic interpersonal stratagems, and diminished levels of integrity and affability (e.g., Jonason & Buss, 2012; Jones & Paulhus, 2009; Lee & Ashton, 2005). In sum, Diller et al. (2021, p. 118) concluded that DT traits have distinctive but shared characteristics concerning “low ethical, moral, agreeable, and interpersonal behavior.” Ultimately, of more significance to the current investigation, research has indicated high associations between the three components of DT (e.g., Paulhus & Jones, 2015). In that respect, and notwithstanding the conceptual differences between the components of the Dark Triad, in a comprehensive study of harmful behaviors in the workplace and their effect on counter-productive behaviors (CWBs), Miao et al. (2023) found that among other personality traits, the DT, as a distinctive construct, was the most significant predictor of CWBs. Indeed, in our study (see Method below), we employ “the Dirty Dozen” (Jonason & Webster, 2010), a concise, flexible, and validated measure of the Dark Triad. The Positive Attributes of the Dark Triad While the discussion so far has emphasized the adverse outcomes of the Dark Triad, as indicated, it is relevant to stress that empirical evidence can be found demonstrating that positive links exist between the Dark Triad and beneficial organizational outcomes, such as high levels of organizational and individual performance where, for instance, as indicated above, the apparent ‘negative’ behaviors prove to be a worthwhile and effective asset to the organization (e.g., Brownell et al., 2021; Cesinger et al., 2023; Haar & de Jong, 2023). For instance, concerning the first trait among the three DT attributes, Szabó et al. (2023) observed that recent research revealed strong relationships between subclinical narcissism and work motivation, resilience, and stamina (e.g., Papageorgiou et al., 2019; Szabó et al., 2023). However, Brownell et al. (2021) added the caveat that while the grandiosity, confidence, and desire for power associated with narcissism might lead to increased motivation and goal achievement, these positive outcomes are limited to narrow competitive circumstances. Furthermore, the price paid is that the narcissist’s egotistical behaviors are often at the expense of exploited colleagues who must contend with a disagreeable work environment that chokes cooperation in the long term. Furthermore, examining the relationship between DT in senior managers and organizational commitment among their employees, Cesinger et al. (2023) indicated that strategic thinking and calculated decision-making associated with Machiavellianism can contribute to positive identification and task performance, indirectly linked to organizational commitment. The authors concluded that while Machiavellian leaders might be assertive and decisive in dealing with immediate and short-term complex issues, in the long term, their strong-arm schemes damage confidence and raise ethical concerns. Lastly, while primarily associated with negative traits, some research suggests a link between psychopathy and charisma and persuasiveness, which could be beneficial in short-term sales or negotiations. For example, McCarthy et al. (2017) indicated that psychopathic CEOs could achieve higher firm performance in competitive environments but, once again, at the cost of poor interrelationships, ethical issues, and excessive employee turnover. Despite the above caveats, how can these findings be reasoned and reconciled? Possibly, those scoring high on the Dark Triad in their search for social affirmation, admiration, and respect – as well as in quest of more power and impact on organizational management – invest abundant energy, ingenuity, and effort to boost the organization’s effectiveness and excel, particularly in a context of fierce market competition. As such, we hypothesized that: H3a: The superior’s Dark Triad may moderate the mediating role of LMX in the association between the superiors’ political skills and individual performance. H3b: The superior’s Dark Triad may moderate the mediating role of LMX in the association between the superior’s political skills and organizational performance. To conclude, the current study empirically examines the following theoretical model (Figure 1), which ultimately aims to enlarge the network of constructs, leading to a more profound understanding of the role of the perception of positive political behavior in leading to individual and organizational performance, with particular emphasis on the possible mediating effect of LMX and the moderating effect of DT between LMX and job performance. Figure 1 Research Model.   Note. LMX = leader-member exchange; Dark Triad = Narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy. We collected self-reported data from employees to test the hypothetical relationship among the variables. The employees assessed their direct superior’s use of positive superior political skills and their LMX relationship with the superior. They were requested to assess their personal (individual) performance and the company’s organizational performance. Finally, the employees were asked to assess the level of their superior’s Dark Triad characteristics. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was designed to examine the research hypotheses (H1 to H3). Method Participants The sample consisted of 318 employees, of which 55% were men and 45% were women between the ages 21-73 (M = 41.63, SD = 11.32). Regarding education, 36% had completed a high-school education, 44.70% held a BA, and 19.30% had an MA or above. In addition, their job tenure ranged between 1 and 42 years (M = 8.77, SD = 6.83). The employees held a non-managerial role. 76.7% were full-time employees, and 23.30% were part-time employees. Respondents participated in the survey voluntarily, and the questionnaires were administered and distributed through Qualtrics. We assured anonymity and discretion regarding the participants’ identities and the data derived from the research. Moreover, at the beginning of the questionnaire, we incorporated a conscious consent question asking for the subjects’ agreement to participate. Furthermore, in the body of the survey, we assured the participants of our respect for the principle of data confidentiality throughout the entire stages of the research program: collection, processing, storage, dissemination, and archiving. The data became anonymous; the respondents could not be identified. Measures Organizational Performance. It was gauged by a 6-item measure, the items of which were derived from Koopmans et al. (2014) and rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) to assess employees’ organization-related performance behaviors. For example: “Adheres to informal rules devised to maintain order.” The present study’s reliability, based on Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, was adequate (α = .82). Individual Performance. It was gauged by a 14-item measure derived from Koopmans et al. (2014), rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) to assess employees’ self-assessed individual performance. For example: “I managed to plan my work so that it was done on time.” In the present study, reliability was adequate (α = .87). Leader-Member Exchange (i.e., the quality of the LMX relationships). It was measured using Scandura and Graen’s (1984) seven-item scale (e.g., “How well does he/she recognize your potential?”; “I have enough confidence in him/her and would defend and justify his/her decision if he/she was not present to do so”). Cronbach’s α for this scale was high at α = .94. Superior’s Political Skills. They were measured by a 17-item Political Skill Inventory (Ferris et al., 2005). The scale, initially a self-reporting measure, was converted to assess the respondent’s immediate superior. Sample items are: “Spends a lot of time and effort at work networking with others” and “Can adjust his/her behavior and become the type of person dictated by any situation.” The Cronbach’s α for this scale based on the study sample was high at α = .90. Superiors’ Dark Triad. These attributes were measured using Jonason & Webster’s (2010) 12-item questionnaire devised to measure narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism The Cronbach’s alpha of this variable was high (α = .95). Statistical Analysis The descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among variables of interest were calculated using SPSS version 29.0 for Windows. The data analysis employed structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine the measurement and structural models. The data were analyzed using AMOS software. The model fit index included root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), chi-squared distribution, Incremental Fit Index (IFI), and the normed fit index (NFI). The bias-corrected bootstrap method was used to examine the significance of the mediation effect. Specifically, 5,000 bootstrap samples were used to determine the bias-corrected 95% confidence interval. The moderated mediation analysis of the indirect effect of Dark Tirad on the association between superior political skills and performance measures through the mediating role of LMX was tested using SEM with AMOS 29. This moderated mediation analysis measures the latent constructs and tests hypothesized relationships between constructs within a single framework (structural model). It multiplies the indicators of the latent variables (independent variables) to create moderator variable indicators, which measure the interaction term in the path model. The indicators of the latent product variable are computed by multiplying the indicators of the latent variables, which interact with each other. Path significance was often combined with indirect effects or simple slopes at different levels of the moderator. This approach provides a solid basis for controlling measurement error and increasing statistical power (Cortina et al., 2021). Table 1 Measurement Model’s SEM Analyses and Comparisons (employee sample)   Note. 1 90% CI; 2 base = original model as depicted in Figure 1; 3 performance variable combined as one variable instead of its two measurements 4 all five variables combined as one continuous variable instead of two; NFI = normed fit index; IFI = incremental fit index; CFI = comparative fit Iindex; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation. Results Preliminary Analysis and Descriptive Statistics Before testing the hypothesized model, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis. (CFA). The CFA consisted of five variables: superior political skills (17 items), LMX (7 items), Dark Triad (12 items), organizational performance (6 items), and individual performance (14 items). A parceling procedure was used for superior political skills, individual performance, and Dark Triad measures. Individual performance consisted of three parcels, while superior political skills consisted of four parcels. Based on Little et al.’s (2002) recommendation, superior political skills and organizational performance included random parceling based on the unidimensional of the measurements, while the Dark Triad parcels consisted of the three theoretical underlying the three aspects of the Dark Triad concept (Narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism). This aggregation method is often used to create several indicators for a latent construct, thus (1) decreasing the error emanating from the measurement itself, (2) minimizing the probability of developing spurious correlations, and (3) increasing the points of the scale(s) (Little et al., 2002; Matsunaga, 2008; Neff et al., 2017). In the current study, each parcel was found to be normally distributed. The employees’ measurement model comprised all the observed items (and parcels) that loaded more than .50 in their latent factor. The measurement model showed an acceptable fit with the data, χ2(751) = 1201.66, p = .000, χ2/df = 1.60, CFI = .91, NFI = .91, TLI = .90, and RMSEA = .06. Overall, the CFA fit indices support the hypothesized model (Hair et al., 2010). As indicated in Table 1, the five-factor CFA for employee measurements showed an acceptable fit with the data. In all CFAs, the hypothesized five-factor model exhibited a significantly better fit than the four-factor model, Δχ2(4) = 232.42, p < .001, and the single-factor model, Δχ2(10) = 1580.49, p < .001. Table 2 Pearson Correlations Natrix (N = 318) for Employee Sample   Note. Performance-I = interpersonal dimension of performance behaviors; performance-O = organizational dimension of organizational performance behaviors. ** p < .01, *** p < .001. Table 3 Moderation and Mediation Effects - Employee Sample   Note. CI = confidence interval; SE = standard error; bootstrapping = 5,000; LL = lower limit of CI; UL = upper limit of CI. Means, standard deviations, and correlations are presented in Table 2. Superior political skills were positively associated with individual and organizational performance, thus supporting H1a and H1b. LMX was positively related to superior political skills and performance outcomes. Finally, the Dark Triad was negatively associated with organizational performance, individual performance, superior political skills, and LMX. Hypothesis Testing The Structural Equation Model (AMOS v.29) was employed to examine the moderating role of the Dark Triad on the indirect relationships between superior political skills and performance through LMX. The model was calculated, while the interaction was based on duplicating the latent variables of LMX and Dark Triad (Cortina & Areguin, 2021). The results provided a good model fit with the data: χ2 = 239706.87; χ2/df = 2.95; CFI = .93; NFI = .90, IFI = .93; RMSEA CI90% = .07 [.07, .08]; SRMR = .09. The outputs of AMOS are shown in Table 3 and Figure 2. Figure 2 Path Analysis and Standardized Regression Coefficients for the Research Model (employee sample).   Study 1 (employees; N = 318); LMX = leader-member exchange; Dark Triad = Narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy. ***p < .001. As indicated in Table 3 and Figure 2, superior political skills were positively related to LMX (β = .82, p < .001). A significant positive relationship between LMX and individual performance as organizational performance was found (β = .45, p < .001; β = .43, p < .001). The SEM technique used a 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval with 5,000 bootstrap resamples to test the direct and indirect effects. Mediation exists if zero is not between the indirect effects (95% confidence interval) (Hayes, 2018). In addition, the key requirement to establish a full mediation effect is that an indirect effect (a × b) exists, and a direct effect (c) does not exist. Partial mediation exists when the indirect and direct effects are significant and point in the same direction (Zhao et al., 2010). According to the results of the AMOS analysis, LMX mediates the relationship between superior political skills and individual performance (indirect effect = 0.26, SE = 0.08, p < .001, 95% CL [0.12, 0.42]), thus supporting H2a. The direct effect of superior political skills on individual performance is non-significant; therefore, the results suggested a full mediation effect. In addition, LMX mediated the relationship between superior political skills and organizational performance, while non-significant associations were found in the direct path between superior political skills and organizational performance (indirect effect = 0.20, SE = 0.06, p = 004, 95% CI [0.07, 0.33]), thus supporting H2b. To test the moderated mediation model relationship, Hayes (2013) suggested four conditions under which this moderated mediation exists. The suggestions are that there should be positive significant levels regarding i) the association between exogenous and endogenous, ii) the interaction of moderator and mediator on endogenous, and iii) the relationship between the mediator and the endogenous variable. Furthermore, at low and high levels for the moderator, the degree of conditional indirect effect must be different. As indicated, moderated mediation may occur when a moderator × independent variable interaction is observed (because of the difference in independent variable to the mediator and the mediator to dependent variable paths). Thus, there is a need to confirm that the LMX x Dark Triad interaction predicts performance. Indeed, the Dark Triad moderated the relationship between LMX and individual performance (β = -.29, p < .001). The association between LMX and individual performance is positive and significant when the employee reports lower levels of Dark Triad (β = .40, p < .001) but non-significant under higher levels of Dark Triad (β =.06, p = .350) (see Figure 3). The results indicated that the mediation path is significant under lower levels of the Dark Triad (indirect effect = 0.45, SE = 0.10, 95% CI [0.25, 0.65], p < .001) but non-significant under higher levels of the Dark Triad (indirect effect = 0.08, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [-0.06, 0.21], thus supporting H3a. Figure 3 The Moderating Role of the Dark Triad on the Association between LMX and Individual Performance./   However, the Dark Triad does not moderate the relationship between LMX and organizational performance (β = .01, p = .84), and it did not moderate the mediation model of superior political skills on organizational performance through LMX; thus, H3b was not supported. To rule out alternative explanations, we ran some models. We examined the MODEL 8 option and tested whether Dark Triad moderates the mediation path from organizational politics to performance via LMX. In addition, we examined both MODEL 8 and Model 14 while testing whether performance mediates the associations between organizational politics and LMX. All two alternative models presented a non-significant moderated mediation index. (The results can be sent upon request). Study 2: Replication via Managerial Sample One of the major limitations of Study 1 was that the sample was based on an employee sample. In the organizational domain, managers play a critical role in shaping both performance outcomes and OP initiatives. Therefore, this study generalized Study 1 finding among a managerial sample. Specifically, we examined the following hypotheses: H4a: Superiors’ OP is positively associated with managers’ performance. H4b: Superiors’ OP is positively associated with managers’ evaluation of the organizational performance. H5: LMX mediates the association between superior OP and managers’ evaluation of individual and organizational performance. H6a: Superiors’ Dark Triad moderates the mediating role of LMX in the relationship between superiors' OP and managers’ individual performance. H6b: Superiors’ Dark Triad moderates the mediating role of LMX in the relationship between superiors' OP and organizational performance. Method Participants The sample consisted of 297 managers, 60.30% of whom were men and 39.70% were women between the ages of 21 and 77 (M = 44.44, SD = 11.55). Regarding education, 25.60% had completed a high-school education, 47.50% held a BA, and 26.90% had an MA and above. In addition, regarding job tenure, tenure ranged between 1 year and 39 years (M = 10.71 years, SD = 7.79), while 91.9% were full-time employees and 9.10% were part-time employees. Respondents participated in the survey voluntarily, and the questionnaires were administered and distributed through Qualtrics. We assured anonymity and discretion regarding the participants’ identities and the data derived from the research. Moreover, at the beginning of the questionnaire, we incorporated a conscious consent question asking for the subjects’ agreement to participate. Furthermore, in the body of the survey we assured the participants of our respect for the principle of data confidentiality throughout the entire stages of the research program: collection, processing, storage, dissemination, and archiving. The data became anonymous; the respondents could not be identified. Measures Organizational Performance. Organizational performance was gauged by a 6-item measure derived from Koopmans et al. (2014), rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) to assess employees’ organizational behaviors. For example: “Adheres to informal rules devised to maintain order.” In the present study, reliability was adequate (α = .80). Managers’ Individual Performance. It was assessed by a 14-item measure derived from Koopmans et al. (2014), rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) to assess employees’ organizational behaviors. For example: “I managed to plan my work so that it was done on time.” In the present study, reliability was high (α = .88). Leader-Member Exchange. Leader-member-exchange (i.e., the quality of the LMX relationships) was established employing Scandura and Graen’s (1984) seven-item scale (e.g., “How well does he/she recognize your potential?”; “I have enough confidence in him/her that I would defend and justify his/her decision if he/she were not present to do so”). Cronbach’s α for this scale was high at α = .93. Superior’s Political Skills. These skills were measured by a 17-item political skill inventory (Ferris et al., 2005). The scale, initially a self-reporting measure, was converted to assess the respondent’s immediate superior. The Cronbach’s α for this scale based on the study sample was high at α = .90. Superior’s Dark Triad. The managers were asked to assess their direct superior personality qualities. We used the 12-item questionnaire devised to measure Narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism (Jonason & Webster, 2010). The Cronbach alpha of this variable was high (α = .95). Statistical Analysis Like study 1, the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among variables of interest were calculated using SPSS version 29.0 for Windows. The data analysis employed structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine the measurement and structural models. The data were analyzed using AMOS software. The bias-corrected bootstrap method was used to explore the significance of the mediation effect. Specifically, 5,000 bootstrap samples were used to determine the bias-corrected 95% confidence interval. The moderated mediation analysis of the indirect effect of Dark Tirad on the association between supervisor political skills and performance measures through the mediating role of LMX was tested using SEM with AMOS 29. The indicators of the latent product variable are computed by multiplying the indicators of the latent variables, which interact with each other. Path significance was often combined with indirect effects or simple slopes at different levels of the moderator (Cortina et al., 2021). Results Preliminary Analysis and Descriptive Statistics SEM confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were carried out before testing the hypothesized model. The CFA consisted of five variables: superior political skills (17 items), LMX (7 items), superior Dark Triad (12 items), organizational performance (6 items), and managers’ individual performance (14 items). A parceling procedure was used for superior political skills, individual performance, and Dark Triad measures. Individual performance consisted of three parcels, while superior political skills consisted of four parcels. Based on Little et al.’s (2002) recommendation, superior political skills and organizational performance included random parceling based on the one-dimensionality of the measurement, while the Dark Triad parcels consisted of three theoretical underlying factors of the Dark Triad concept (narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism). This aggregation method is often used to create several indicators for a latent construct, thus (1) decreasing the error emanating from the measurement itself, (2) minimizing the probability of developing spurious correlations, and (3) increasing the points of the scale(s) (Little et al., 2002; Matsunaga, 2008; Neff et al., 2017). In the current study, each parcel was found to be normally distributed. The employees’ measurement model comprised all the observed items (and parcels) that loaded more than .41 in their latent factor. The measurement model showed an acceptable fit with the data, χ2(215) = 558.27, p = .000, χ2/df = 2.13, CFI = .94, NFI = .90, IFI = .89, SRMR = .05, RMSEA = .07. Overall, the CFA fit indices support the hypothesized model (Hair et al., 2010). As indicated in Table 4, the five-factor CFA for employee measurements showed an acceptable fit with the data. In all CFAs, the hypothesized five-factor model exhibited a significantly better fit than the four-factor model, Δχ2(4) = 195.99, p < .001, and the single-factor model, Δχ2(10) = 1591.59, p < .001. Table 4 Measurement Model’s SEM Analyses and Comparisons (manager sample)   Note. 1 90% CI; 2 base = original model as depicted in Figure 1; 3 performance variable combined as one variable instead of its two measurements; 4 all five variables combined as one continuous variable instead of two; NFI = normed fit index; IFI = incremental fit index; CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation. Means, standard deviations, and correlations are presented in Table 5. Superior political skills were positively associated with individual and organizational performance, thus supporting H4a and H4b. LMX was positively related to superior political skills as well as to performance outcomes. Finally, the Dark Triad was negatively associated with organizational performance, individual performance, and LMX. Table 5 Pearson Correlations Matrix for Managers (N = 297)   Note. Performance-I = interpersonal dimension of performance behaviors; performance-O = organizational dimension of organizational performance behaviors. ** p < .01, *** p < .001 Hypothesis Testing The structural Equation Model (AMOS v.29) was employed to examine the moderating role of the Dark Triad on the indirect relationships between superior political skills and performance through LMX. The model was calculated, while the interaction was based on duplicating the latent variables of LMX and Dark Triad (Cortina & Areguin, 2021). The results provided a good model fit with the data χ2(234) = 464.08, χ2/df = 2.76, CFI = .93, NFI = .89, IFI = .93, RMSEA [CI90%] = .07 [.07, .08], SRMR = 0.06. The outputs of AMOS are shown in Table 6 and Figure 4. Figure 4 Path Analysis and Standardized Regression Coefficients for the Research Model (manager sample).   Note. Study 2 (employees; N = 297). LMX = leader-member exchange; Dark Triad = narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy. *p < .05, ***p < .001. Table 6 and Figure 4 indicate that superior political skills were positively related to LMX (β = .77, p < .001). A significant positive relationship was found between LMX individual and organizational performance (β = .24, p < .05; β = .43, p < .001). Table 6 Moderation and Mediation Effects - Manager sample   Note. CI = confidence interval; SE = standard error; bootstrapping = 5,000; LL = lower limit of CI; UL = upper limit of CI. The SEM technique used a 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval with 5,000 bootstrap resamples to test the direct and indirect effects. According to the results of AMOS analysis, LMX mediates the relationship between superior political skills and individual performance (indirect effect = 0.13, SE = 0.06, p < .05, 95% CI [0.02, 0.24]). The direct effect of superior political skills on individual performance is significant (β = .25, p < .01); therefore, the results suggested a partial mediation effect. In addition, LMX fully mediated the relationship between superior political skills and organizational performance, thus supporting H4b (indirect effect = 0.19, SE = 0.09, p < .05, 95% CI [0.05, 0.39]). The mediation established here is full mediation because the direct effect between superior political skills and organizational performance is non-significant (β =.17, p = .140). These results support H5. Dark Triad moderated the relationship between LMX and individual performance (β = -.26, p < .001). To confirm the direction of the interaction effect, a procedure for plotting the simple slope effect was applied as one standard deviation above and below the mean of the Dark Triad (see Figure 5). As expected, the association between LMX and individual performance is significant under lower levels of Dark Triad (β =.32, p <.001) but non-significant under higher levels of Dark Triad (β = .06, p = .920). Figure 5 The Moderating Role of the Dark Triad on the Association between LMX and Individual Performance.   The moderated mediation effect index was also examined and indicated a significant result (indirect effect = -0.02, SE = 0.01, p < .05, 95% CI [-0.06, -0.002]). The results indicated that the mediation path is significant under lower levels of Dark Triad (indirect effect = 0.25, SE = 0.08, p < .001, 95% CI [0.12, 0.40]) but non-significant under higher levels of Dark Triad (indirect effect = 0.04, SE = 0.07, p = .910, 95% CI [-0.13, 0.14]), thus supporting H6a. However, the moderated mediation index was non-significant for organizational performance; thus, H6b was not supported. Like in study 1, we ran alternative statistical models. The alternative models provided a non-significant moderated mediation index. (The results can be sent upon request). This study aimed to explore the positive side of superior political skills and to assess the impact of perceived positive politics on perceived performance. A comparison between the two studies reported here shows almost complete similarity in the pattern of the relationships among the study variables. This discussion, therefore, pertains to both samples. The results support the study’s theoretical model. It was found in both samples that the perception of the superior as an effective political player was significantly correlated with the perception of individual and organizational performance. This finding aligns with recent literature that highlights the affirmative components of organizational politics and the positive role afforded by political perceptions (Hochwarter, 2012; Landells & Albrecht, 2017). As opposed to common (mis)conceptions of organizational politics, at the center of the research on “positive” politics are the perceptions that political activity can have a positive/favorable impact on individuals and groups within the organization and, therefore, on the organizations themselves (Hochwarter, 2012, pp. 27-28), including job performance. In the present study, the measure of positive politics in the organization specifically focused on assessing the superior as a skilled political player who is a good communicator, understands people and makes them feel good, and is good at building relationships. However, a politically skilled superior may utilize this capability for different purposes. Such capabilities can be directed toward the good of the organization and the employees. Nevertheless, it may be used to manipulate and exploit the employees to serve the superior’s needs and interests. For instance, Munyon et al.’s (2015) meta-analysis indicated that task performance was indeed envisaged by political skill, but only after controlling personality dispositions and general cognitive functioning (i.e., Big Five personality traits). Notably, in a test of indirect relationships, the results of the meta-analysis indicated that the association “political skill–task performance” is mediated partially by self-efficacy and personal reputation. The role of LMX in the hypothesized model as a mediator between the perception of superior political skills and performance can be interpreted as follows: Further to the perception of the superior’s political skill, the LMX level adds an important dimension to the subordinate’s interpretation of the superior’s political style. The higher the LMX level, the greater the confidence in superiors’ intentions and the level of trust in them. Therefore, when the superior is perceived as trustworthy and highly skilled politically, it is only natural that the subordinate is inclined to aim at a higher level of performance. The lower the LMX level, the less relevant the perception of the superior’s political skill in affecting both the subordinate’s and organizational performance. The results pertaining to the role of the Dark Triad in the model are more complex and require some speculative suggestions. When the superior is rated low on the Dark Triad scale, it was found that LMX is significantly and positively related to individual performance. However, when the superior is rated as high DT, LMX is unrelated to individual performance. This finding may suggest that high DT supervision overrides the effect of the quality of the superior-subordinate relations. It appears that the clear and trusting superior-subordinate relationship established in high LMX situations tends to affect the subordinate’s performance positively. However, when the superior is high on DT, the negative impact on the relationship with the superior cancels out the potential positive impact of LMX on performance. For organizational performance, no DT moderating effect was found. It may be suggested that a high DT personality may elicit strong negative reactions on the part of the subordinate. As indicated, a consequent attempt to play down individual performance in the exchange may occur and affect the assessment of individual performance. Yet, when it comes to organizational performance, employees’ performance is less directly related to their personal situation than with individual performance. That is to say that the perception of one’s superior is less associated with the assessment of the overall organizational performance but is more relevant to the perception of individual performance. In conclusion, the study contributes an important insight into the growing body of research attempting to understand the complex effect of managers’ political skills on organizational performance. The study focuses on the personality and interpersonal aspects of this issue and highlights the role of two specific variables previously unexplored in this context, namely LMX and the superior’s DT. We have shown – in two separate studies – that these variables play a key role in determining the connection between the superior’s political skill and performance examined at the individual as well as the organizational level. We hope that this study paves the way for additional research in this direction. Limitations A significant strength of this study is that the results are based on two independent samples and show almost similar results. This adds confidence to the validity of the findings and provides a strong case for further research in this direction. However, this study has a notable weakness that cannot be overlooked. Both dependent and independent variables were measured using a single source, namely the employees. We hope that future research addresses this prevalent limitation and supports the present research findings based on multiple sources of data. Practical Implications The results of this study may offer some implications for the implementation of strategies and practices of management development in work organizations. We suggest that the practice of positive political tactics will be incorporated into the training and development of lower and mid-level management. Management should become aware of the potential benefit of this supervisory style to performance. Moreover, the process of supervisory level selection and promotion may incorporate this consideration. At the same time, organizational training systems may pay particular attention to the nature of employee-superior relations (LMX) and guide supervisory staff to establish and maintain high standards of LMX relations with their subordinates. The negative impact of the Dark Triad characteristics in this context should be minimized through careful selection and promotion practices as they pertain to supervisory development and promotion. Greater awareness to the importance of the above variables could contribute to the quality of management practices and, eventually, to personal and organizational performance in organizations. Suggestions for Future Research Exercising political skills in organizations, the reaction of coworkers and subordinates to it, and the eventual impact on performance both at the individual and the organization level involve the encounter of personalities and the activation of a wide range of emotional reactions. We believe that the present literature on this subject is far from completely understanding this area. We therefore suggest that future research should further explore the role of personality characteristics and patterns of social relationships within the framework of positive political skills and their implementation in organizations. For example, we propose that the present study be followed by attempting to look at the specific dimensions of the key variables of the present research, namely, the Political Skill Inventory (PSI) and the Dark Triad (DT). PSI consists of four dimensions (Ferris et al., 2005). DT has three personality characteristics (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Attempting to examine some of those specific dimensions and their interaction more closely will take us a step forward in understanding the role of political skills in organizations. As suggested earlier, such investigations should attempt to incorporate objective performance measures to ensure the best level of validity and confidence in future results. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest Cite this article as: Tziner, A., Drory, A., & Reizer, A. (2024). Could positive political skills work to the benefit of work performance? Is it possible? Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 40(2), 89-102. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2024a8 References |

Cite this article as: Tziner, A., Drory, A., & Reizer, A. (2024). Could Positive Political Skills Work to the Benefit of Work Performance? Is it Possible?. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 40(2), 89 - 102. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2024a8

Correspondence: atziner@netanya.ac.il (A. Tziner).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS