The Big Five, Dark Personality, Moral Disengagement and Counterproductive Behavior at Work

[Los Big Five, la personalidad oscura, la desconexiĂłn moral y las conductas contraproductivas en el trabajo]

María Patricia Navas1, Tania París2, Jorge Sobral2, and Silvia Moscoso2

1University of Zaragoza, Spain.; 2University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain.

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2025a4

Received 7 February 2025, Accepted 2 April 2025

Abstract

This study examines the relationship between Big Five personality traits, dark personality (i.e., Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy), and moral disengagement in relation to counterproductive behaviors at work (CWB). The sample consisted of 118 felons convicted of economic crimes (M = 43.81, SD = 10.75). Results revealed a significant association between moral disengagement and dark personality traits and CWB. Moreover, the variance explained by the dark personality was notably higher than that accounted for by the Big Five model. Specifically, moral disengagement and psychopathy significantly increased the variance explained by the Big Five (ΔR² = .17). Additionally, Browne’s coefficient (ΔRcv² = .15) suggests that this increase is generalizable to larger, similar samples. These findings support previous research on the role of the Big Five, dark personality and moral disengagement in shaping workplace behavior and provide valuable insights for managers and HR professionals seeking to mitigate CWB.

Resumen

Este estudio examina la relación entre los rasgos de personalidad de los Big Five, la personalidad oscura (es decir, maquiavelismo, narcisismo y psicopatía) y la desconexión moral asociadas a las conductas contraproductivas en el trabajo (CWB). La muestra consistió en 118 delincuentes condenados por delitos económicos (M = 43,81, DT = 10,75). Los resultados mostraron una asociación significativa entre la desconexión moral y los rasgos oscuros de personalidad con los CWB. Además, la varianza explicada por la personalidad oscura fue notablemente superior a la explicada por el modelo de los Big Five de personalidad. En concreto, la desconexión moral y la psicopatía aumentaron significativamente la varianza explicada por los Big Five (ΔR² = .17). Además, el coeficiente de Browne (ΔRcv² = .15) sugiere que este aumento es generalizable a muestras más grandes y similares. Estos resultados respaldan investigaciones anteriores sobre el papel de los Big Five, la personalidad oscura y la desconexión moral en la configuración del CWB en el lugar de trabajo, y proporcionan información valiosa para los directivos y los profesionales de RRHH, que tratan de mitigar la CWB.

Palabras clave

Big Five, Personalidad oscura, DesconexiĂłn moral, Conducta contraproductiva en el trabajoKeywords

Big Five, Dark personality, Moral disengagement, Counterproductive behavior at workCite this article as: Navas, M. P., París, T., Sobral, J., & Moscoso, S. (2025). The Big Five, Dark Personality, Moral Disengagement and Counterproductive Behavior at Work. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 41(1), 27 - 38. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2025a4

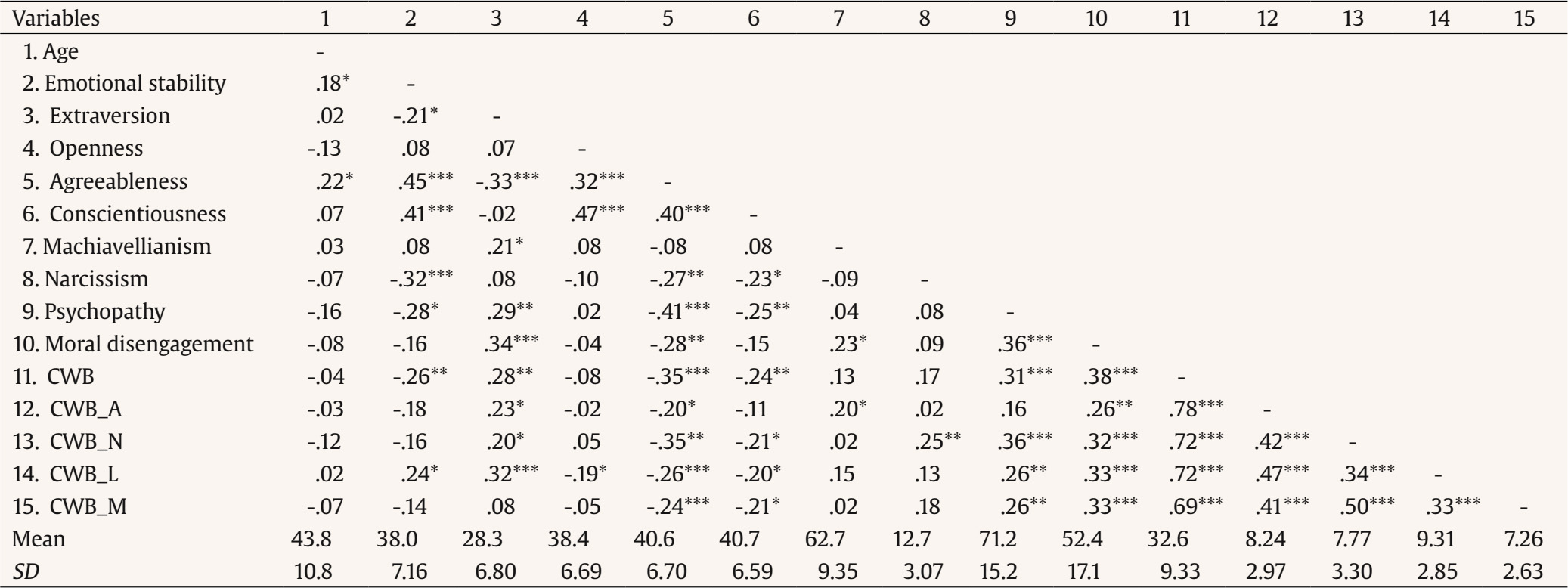

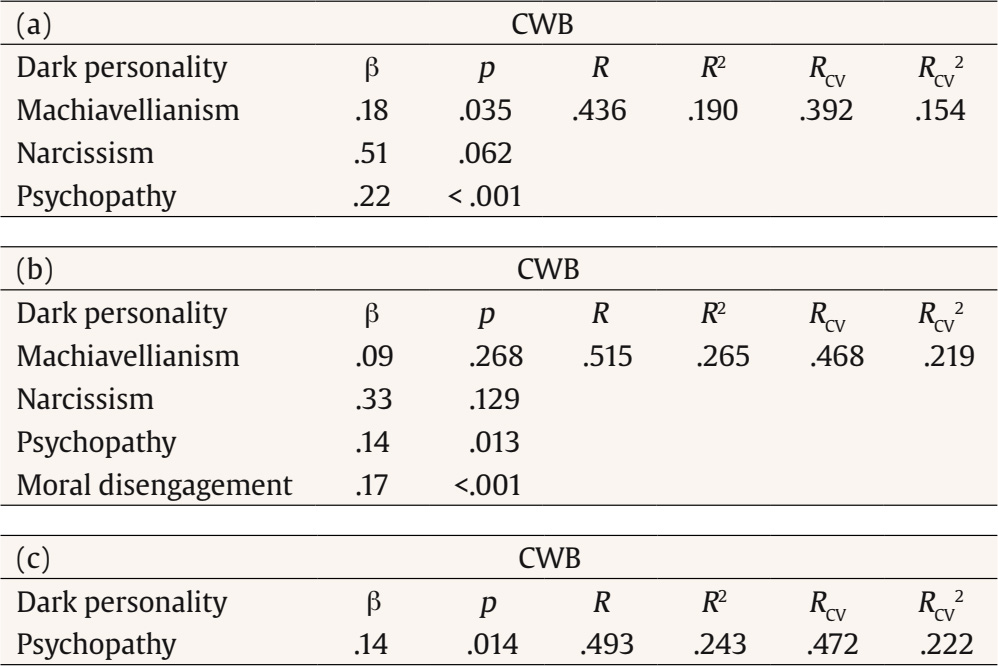

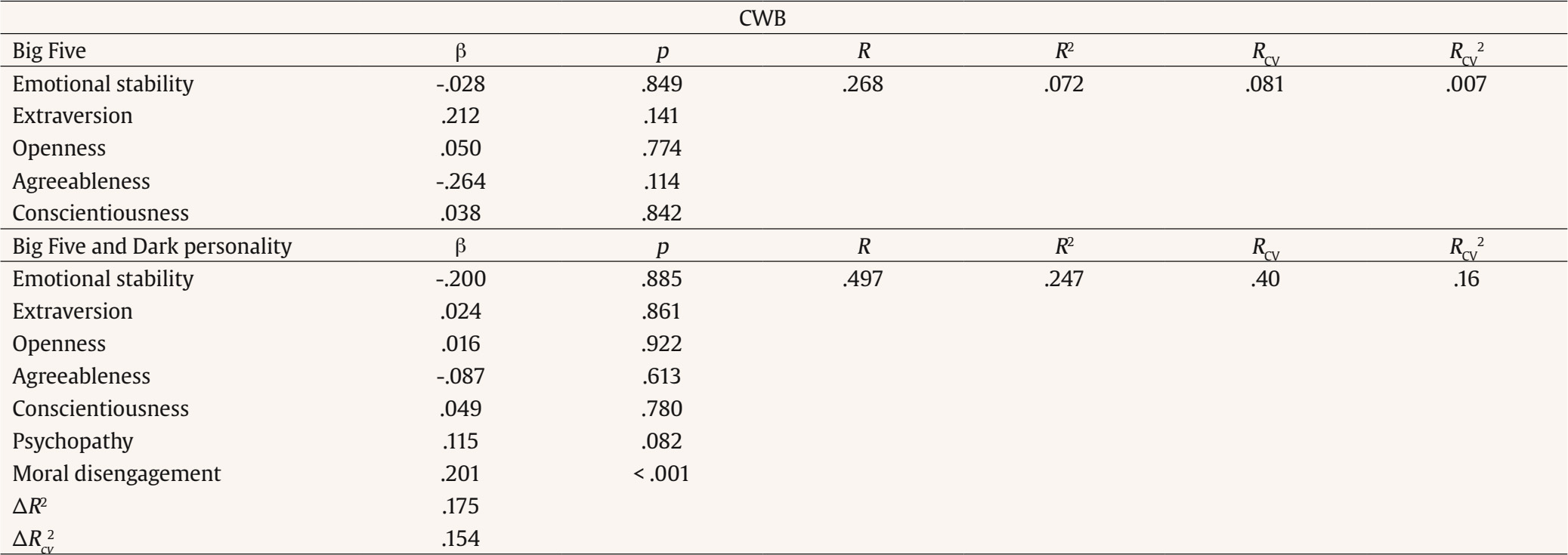

Correspondence: mnavas@unizar.es (M. Patricia Navas).Interest concerning counterproductive and deviant behaviors at work (CWB) has grown sharply in the last three decades and now measures of counterproductive work behaviors (CWB) are included as criteria in many published studies (Rotundo & Spector, 2017; Salgado et al., 2013). An important characteristic of these behaviors is that they are voluntary (i.e., intentional) and this characteristic allows the distinction between those behaviors that are counterproductive and those that are mere hazards. For example, an accident or an injury will be considered a counterproductive behavior if they are a result of avoiding the use of preventive measures or norms. In this sense, Spector & Fox (2005) defined CWB as intentional acts that harm organizations or people in organizations. This definition focuses on the intentional behavior itself rather than on the consequences of the behavior. CWB are pervasive and costly both to organizations and to employees’ well-being (Mount et al., 2006). Employee deviant behavior violates institutionalized expectations or norms and, in doing so, threatens the well-being of an organization and/or its members (Robinson & Bennet, 1995). Greenberg and Scott (1996) formulated two forms of employee deviance: production deviance, or the violation of norms regarding the minimal quality and quantity of work (habitual lateness is an example), and property deviance, behaviors designed to damage or acquire property or co-worker assets (e.g., theft). Robinson and Bennett (1995) also discuss interpersonal forms of deviance, such as political game playing. The range of counterproductive behaviors includes both minor acts (e.g., lateness) and even criminal activities that may be directed towards individuals or the organization (e.g., scams or physical aggressions) (Rotundo & Spector, 2017). Since the early 1980s, several authors have developed different taxonomies of counterproductive behaviors in order to produce a useful classification for both research and for practice in organizations. For example, Hollinger and Clark (1982, 1983) identified a large list of counterproductive behaviors and proposed that these could be classified into two broad categories. The first one was property deviance, that was composed of behaviors such as theft, property damage, and misuse of discount privileges. The second category was production deviance, that included not being on the job in working hours (e.g., absence, tardiness or long breaks) and behaviors that detract from production (e.g., drug and alcohol use, intentional slow or sloppy work). Robinson and Bennett (1995) found that CWB varied along two dimensions. The first one referred to the extent to which behaviors are interpersonal and harmful to individuals versus non-interpersonal and harmful to organizations. The second dimension reflects the extent to which these behaviors are mild versus serious. The combination of these two dimensions produced four categories of behaviors: (a) property deviance, including sabotaging equipment, stealing from the company, and accepting kickbacks; (b) production deviance, including leaving early, wasting resources, and intentionally working slowly; (c) personal aggression, including sexual harassment, verbal abuse, and stealing from co-workers; and (d) political deviance, which refers to gossip, blaming co-workers or showing favouritism. Gruys (2000) sets out a rather different approach to counterproductive behavior at work. This author identified 87 different counterproductive behaviors and, using factor analysis methods, reduced them to eleven different categories of CWB, namely (1) theft and related behavior (e.g., the theft of cash or property, misuse of employee discount); (2) destruction of property (e.g., damaging or destroying property, sabotaging production); (3) misuse of information (e.g., revealing confidential information, falsifying records); (4) unauthorised use of time and resources (e.g., wasting time, altering time cards, conducting personal business during work time, working on unsanctioned projects); (5) unsafe behavior (e.g., failure to follow or learn safety procedures); (6) poor attendance (e.g., unexcused absence or tardiness, misuse sick leave); (7) poor-quality work (e.g., intentionally slow or sloppy work); (8) alcohol use (e.g., alcohol use on the job, coming to work under the influence of alcohol); (9) drug use (e.g., drug use on the job, coming to work under the influence of drugs, selling drugs at work); (10) inappropriate verbal actions (e.g., arguing with customers; verbally harassing co-workers); and (11) inappropriate physical actions (e.g., physically attacking co-workers; physical or sexual advances toward co-workers). Spector et al. (2006) proposed a classification of counterproductive work behaviors based on their potential antecedents (underlying motives such as hostility or instrumentality). Accordingly, the CWB types are: (1) abuse against others (e.g., making threats, nasty comments, or ignoring a person); (2) production deviance (e.g., failure to do a task or to do it correctly); (3) sabotage (e.g., intentionally destroying something); (4) theft; and (5) withdrawal (e.g., absence, arriving late, leaving early, or taking longer breaks than authorized). Assessment of Counterproductive Behavior at Work The three more typical ways of assessing CWB are self-report questionnaires, other informants, and archival data. Most studies use self-report questionnaires where people inform on their own behaviors. In fewer cases, other informants (e.g., co-workers, supervisors) report on the employees’ CWB behaviors. These two types of measures can be termed as judgment-based tools. Berry et al. (2012) carried out a meta-analysis in which they compared self-reports and other reports to measure CWB and found that both methods are adequate for measuring CWB. Self-report and other-report methods show, however, some limitations. Self-reports may be biased by social desirability if the informant wants to give a more positive image of him/herself. On the one hand, counterproductive behaviors are by their nature loaded with negative connotations, consequently self-reports of CWB might be biased. On the other hand, employees may underdeclare the extent to which they engage in counterproductive behaviors because they may involve penalties or punishments (Berry et al., 2012; Fox et al., 2007). Another limitation of self-reports might be common method bias, which happens when self-reports of CWB are answered together with self-reports of other relevant variables (e.g., personality inventories) that use the same rating system. This may lead to an artificial inflation of the relationships between variables. Regarding the use of other informants, on the one hand, the main limitation is that, as a matter of fact, because they are deviant behaviors, it is more difficult for other people to have the opportunity to observe them as the employees that commit these behaviors will try to hide them. On the other hand, informing about counterproductive behaviors by third parties might have negative consequences to the informant if they are employees, which in turn may make it less likely that employees will report these behaviors when requested to answer these questionnaires (Fox et al., 2007). The use of archival or objective data is even less common. For example, organizational registers have been used to measure withdrawal behavior, especially absenteeism and turnover (Rotundo & Spector. 2017). However, Fox et al. (2007, p. 43) indicated that “The CWB community is now at the point that more objective, or nonincumbent, measures are needed to further our understanding of the phenomenon.” In this sense, the limitations of self-report measures can be overcome if, instead of using samples of current employees and co-workers, the samples consist of CWB convicted employees. In other words, if the participants are employees that were found guilty of a CWB felony, and because of this they do not need to hide their CWB, then self-reports can be an acceptable tool for measuring CWB, as they typically show good internal consistency coefficients. Big Five and Counterproductive Behavior at Work Since the nineteen nineties, the Five-Factor Model (FFM) of personality has been the most empirically supported model for the examination of the relationships between personality dimensions and occupational criteria (e.g., job performance). The FFM conceptualizes the personality domain as consisting of five broad factors (the “Big Five”), relatively independent from each other, and hierarchically organized (Costa & McCrae, 1992; DeYoung et al., 2013; Goldberg, 1990, 1992; Salgado & De Fruyt, 2005). This model has also served as a taxonomy for the classification of different personality scales and inventories. There are alternative approaches for the conceptualization of personality (e.g., the HEXACO model), but currently the FFM is the most widely accepted approach to the structure of the personality traits. Although the Big Five factors have received a variety of labels over the years, the most common are emotional stability, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Many primary studies and several meta-analyses have been carried out on the relationship between the Big Five and counterproductive behaviors at work. Salgado (2002) conducted a meta-analysis using as criteria absenteeism, accident rate, turnover, and deviant behavior (including actual theft, disciplinary problems, substance abuse, property damage, organizational rule breaking, and other irresponsible behaviors). The findings showed that conscientiousness and agreeableness were valid predictors of the deviant behaviors (-.26 and -.20 respectively). Dalal (2005) conducted a meta-analysis on the relationship between CWB and conscientiousness and the results showed an operational validity of -.38. A meta-analysis by Berry et al. (2007) using the distinction between interpersonal CWB and organizational CWB found similar correlations for emotional stability (-.24 and-.18 for interpersonal and organizational CWB, respectively), openness to experience (-.09 and -.03), and extraversion (.02 and -.07). The results showed relevant differences in the other two personality factors. Conscientiousness correlated -.23 with interpersonal CWB and -.33 with organizational CWB; agreeableness correlated -.46 and -.24 with interpersonal and organizational CWB, respectively. The authors compared their results with Salgado’s (2002) findings and considered that the differences might be due to the levels at which each meta-analysis measured deviance. That is, Berry et al. (2007) used aggregate measures of ID and OD, while Salgado (2002) used narrower behavioral measures (absenteeism, accident rate, turnover, and deviant behavior). In summary, research addressing this question has showed unambiguously that some of the Big Five personality dimensions have substantial relationships with counterproductive behaviors. The strongest relationship is for conscientiousness. Agreeableness and emotional stability are also related with CWB. In all these studies, the measure of CWB was self-reported questionnaires. For their part, Berry et al. (2012), using other-reports (supervisors or co-workers) to measure CWB, found correlations coefficients of -.04, .03, -.10, -.18, and -.15 for emotional stability, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, respectively. Dark Personality and Counterproductive Behavior at Work Traditional personality models, such as the Big Five, have long been recognized as key predictors of job performance (Salgado, 2002). However, the increasing attention towards counterproductive work behaviors has led to a growing interest in examining the impact of dark personality traits as a complement to the traditional Big Five model for capturing these malevolent characteristics. Dark personality, as a malevolent personality profile focused on the pursuit of self-interest, shares the common characteristics of three main personality compounds: Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism. Individuals with these traits share a tendency to be callous, selfish, dishonest, self-promoting, and manipulative in their interpersonal relationships (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). However, these three personality compounds are not equivalent. Paulhus (2014) reports that, although these personalities share high scores on callousness, only the narcissism and psychopathy compounds are high in impulsivity and grandiosity. In addition, of these characteristics only psychopathy is associated with criminality. Empirical evidence has shown different relationships of these three traits with the dimensions of the Big Five model. The study by Muris et al. (2017) indicates that dark personality is the opposite of agreeableness, finding inverse relationships of this dimension with Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism. The same authors found that conscientiousness was negatively associated with Machiavellianism and psychopathy but not with narcissism. Neuroticism was only negatively related to psychopathy (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Extraversion has been positively associated to psychopathy through the impulsivity and constant need for stimulation component of this trait, but Machiavellianism has not shown significant relationships (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Openness was positively related to narcissism (Mathieu, 2021). Research would be expected to consistently highlight a positive correlation between the three dark personality traits and negative workplace outcomes, given the tendency of these individuals to use deception, lying, money, popularity, and social status to elevate themselves and gain power and control over others in an organizational context (Mathieu, 2021). However, empirical evidence on the relationship between dark personality and negative workplace outcomes is far from conclusive, as previous analyses on this topic that simultaneously compare the effects of the Big Five and Dark Triad traits report several results that do not make it clear which personality traits more strongly predict negative workplace outcomes (Ellen et al., 2021; Miao et al., 2023; O’Boyle et al., 2012). O’Boyle et al.’s (2012) meta-analysis attempted to clarify the relationships of dark personality with performance, finding that the three elements of the Dark Triad were positively associated with CWB and explain 28% of the variance of workplace deviance measures. These results were replicated by the findings of the meta-analysis by Miao et al. (2023), which showed the incremental validity of the dark personality model (ρ = .412) over the Big Five model (ρ = -.176) and the HEXACO model (ρ = -.221) for the prediction of negative workplace outcomes. Nevertheless, Ellen et al. (2021) highlighted Machiavellianism and psychopathy as the most important predictors of negative workplace outcomes, while Grijalva and Newman (2014) indicate that narcissism is the dominant predictor of negative workplace outcomes among the dark triad personality elements. Recent research seems to indicate that it is primarily psychopathy that predicts counterproductive behavior at workplace (Bingül & Göncü-Köse, 2024; Ramos-Villagrasa et al., 2025). Accordingly, it seems reasonable to investigate the relationships between both the dark and the Five Factor models of personality for the prediction of counterproductive work behavior, especially since previous studies have analysed these relationships mainly in samples of employees. These findings, although relevant, cannot be directly generalized to other types of samples, such as felons. Given that the factors that influence behavior in work settings may not be the same as in incarceration contexts, it is crucial to explore how these traits manifest themselves in for example individuals incarcerated for economic crimes. A large number of self-report measures exist to assess both the overall presence of the dark personality (Moshagen et al., 2020) and each of its three separate factors. Questionnaires may vary in terms of their length, reliability and validity, as well as their usefulness in different samples (e.g., employees, and felons). Therefore, when conducting dark personality research it is important to carefully choose the questionnaires to be used. The usually longer, more traditional questionnaires such as the NPI (Raskin & Terry, 1988) for the assessment of narcissism, the MACH-IV (Christie & Geis, 1970) for the assessment of Machiavellianism, or the SRP (Hare, 1985) for the assessment of psychopathy should be used if the study design does not have serious time constraints, and are appropriate to the nature of the samples (e.g., clinical or forensic samples). If the study uses large, organizational samples or samples of felons, then short measures composed of items assessing all three factors may be a reasonable substitute for longer questionnaires (Smith et al., 1983). The results found so far on the relationships of the dark triad to counterproductive work behavior have used short scales such as the Dark Triad Dirty Dozen (Jonason & Webster, 2010) or the Short Dark Triad (Jones & Paulhus, 2013) to assess at a subclinical range the presence of these traits in normal populations. Thus, an interesting contribution of this study would be to analyse the relationships that each of the traits that compose the dark triad have with counterproductive work behavior, using samples of convicted felons and extensive questionnaires for this purpose. Moral Disengagement and Counterproductive Behavior at Work Research has shown that moral disengagement (MD) provides incremental validity to the model that uses only measures of dark personality traits for the prediction of workplace deviance (Egan et al., 2015). Bandura et al. (1996) proposed the concept of MD to refer to the cognitive processes involved in justifying, rationalising and maintaining deviant behaviors in the workplace. According to Bandura (1996) MD develops gradually, beginning with the formulation of simple excuses and progressing to the establishment of firmly held beliefs (Navas et al., 2021a). This process ultimately leads to individual disinhibition, which, in turn, heightens the risk of (re)offending in an organizational context (Petruccelli et al., 2017a). For this reason, the study of MD has been approached from two perspectives (Ramos-Villagrasa et al., 2025): as a state and as a trait. As a state, it involves the process of reconstructing moral judgments related to a specific behavior (Bandura, 2016). As a trait, it refers to the individual predisposition to morally disengage, influenced by characteristics such as low scores in agreeableness, low empathy, and guilt, which increase the likelihood of immoral behaviors in an organizational context (Newman et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2019). In fact, MD has been viewed by some authors as a dispositional feature that makes up part of the dark core personality (D factor; Bertl et al., 2017; Moshagen et al., 2020; Zeigler-Hill & Marcus, 2016). Previous studies using the Big Five model have suggested that a low level of agreeableness is the main contributor to MD (Rengifo & Laham, 2022), although MD has also been negatively associated to openness and conscientiousness (Ramos-Villagrasa et al., 2025). Complementarily, the study by Egan et al. (2015) showed that the influence of agreeableness on MD is reduced when the three Dark Triad traits are introduced. In other words, although low scores in agreeableness could initially have an impact on the propensity for MD, the presence of traits like psychopathy and Machiavellianism seems to significantly attenuate this relationship. Furthermore, the study indicated that MD is predicted by the presence of psychopathy and Machiavellianism, highlighting how certain personality traits can predispose individuals to more frequently justify immoral behaviors in an organizational context. However, the relationship of MD with the various factors of (dark and five-factor model) personality in the workplace has not yet been examined in samples of felons incarcerated for economic crime (Ogunfowora et al., 2022). The predisposition to morally disengage has been associated with a dark personality profile in incarcerated adults for predicting other criminal typologies, such as gender-based violence and sexual aggression (Navas et al., 2021b; Petruccelli et al., 2017b). Therefore, the examination of dark and light personality configurations with MD stands out as a central theme in the study of individual differences in general and especially in the workplace (Fernandez-del-Río et al., 2020; Miao et al., 2023). To the authors knowledge, few studies have examined the relationship between the five-factor model of personality, the dark personality and the propensity for MD in prison settings, specifically in populations incarcerated for economic crime, nor their impact on counterproductive work behavior. This gap in the literature is particularly relevant, given that previous research has highlighted the influence of these personality traits on behavior in various work contexts considering only samples of employees (Mathieu, 2021; O’Boyle et al., 2012). Consequently, the main purpose of this study is to analyse how these personality traits may affect the propensity for counterproductive behaviors in a prison setting, thus providing a novel perspective on the behavior of individuals deprived of liberty and contributing to the understanding of these relationships in different contexts. Participants The sample of the current study was composed of 118 men perpetrators of economic crime. Initially, the sample comprised 134 men selected through non probabilistic sampling methods. Intentional sampling was used, as participants were required to have basic literacy skills and to have been convicted of specific crimes. Participants missing more than 5% of the data in all study variables were excluded (Schafer, 1999), as were participants who scored above the 75th percentile or below the 25th percentile in the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Short Form Scale (Gutiérrez et al., 2016) for evaluating simulation or concealment. The sample of economic crime offenders comprised 118 men from prisons in Spain. These participants were convicted of economic crimes and their ages ranged from 22 to 74 (M = 43.81, SD = 10.75). Prison psychology teams provided the following demographic information and reported the following types of economic crime. According to the legal typology of crime in Spain1, 42% were convicted of theft, 34% were convicted of fraud, and the remaining percentage were individuals deprived of liberty for crimes such as social security fraud (2%), tax fraud (6%), extortion (5%), property usurpation (1%), embezzlement (3%), and money laundering (7%). As regards the analysis of recidivism in economic crime, 39.2% reported being repeat offenders in the same type of crime while 48.5% reported being first time offenders. The remaining percentage preferred not to answer this question. However, no statistically significant differences among these participants regarding the presence of previous records or recidivism for similar crimes were found. Also, taking into account the analysis of criminal records for types of crime other than economic crime, 54.6% reported having a criminal record for other types of crime while 36.2% reported no criminal record. The remaining percentage preferred not to answer this question. Regarding other sociodemographic characteristics of the sample, participants self-reported their socioeconomic status as follows: 42.3% as low, 26.2% as lower-middle, 15.4% as middle, 5.4% as upper-middle, and 10.8% as high. Concerning the level of education, according to participant self-reports, 30% had primary education, 39% had secondary education, 14.1% had vocational training, and 16.9% had higher/university education. Finally, in relation to their nationality, the participants indicated that 83.8% were Spanish, and the remaining percentage was of other nationalities. Measures Social Desirability The questionnaire used to evaluate social desirability was the short version of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960; Spanish version by Gutiérrez et al., 2016), which refers to a tendency to present oneself in an overly positive manner. It consists of 18 items rated on a dichotomous scale (true/false) that reflect socially desirable (e.g., “I never hesitate to drop everything if I need to help someone in need”), and undesirable behaviors and traits (e.g., “Sometimes I like to gossip”). The reliability, calculated with the omega coefficient, in the current sample was ω = .73. Sociodemographics Participants were asked about their gender, age, level of education, job experience, socioeconomic status, and criminal status. Counterproductive Behaviors The scale used to evaluate deviant actions and behaviors at work was the Counterproductive Work Behaviors Scale (Salgado, 2020). This scale consists of 20 items for evaluating 4 dimensions of counterproductive behaviors each one composed of 5 items: (1) absenteeism (e.g., “I have voluntarily missed work”), (2) non-compliance with rules (e.g., “I have deliberately violated some company rule for my own benefit”), (3) behaviours related to low effort (e.g.., “I have deliberately worked below my possibilities”) and (4) inappropriate use of resources (e.g. “I have consciously spoiled some work material or tool”). Participants had to indicate for each of the affirmations how often they carried out the described actions using a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The reliability calculated using the omega coefficient, for the overall score of the scale was ω = .87 and was adequate for each of the dimensions: absenteeism (ω = .65), non-compliance (ω = .75), low effort (ω = .57, and inappropriate use of resources (ω = .72). Five-factor Model of Personality The questionnaire used to appraise the Five-factor model of personality was the Description in Five Dimensions system (D5D; Rolland & Mogenet, 2001), which is a widely used Spanish personality inventory based on the five-factor model (FFM; Costa & McCrae, 1992). This questionnaire assesses the Big Five dimensions of emotional stability, introversion, openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness through 55 adjectives (e.g., nervous, reserved, cultivated, compassionate, tidy) rated along a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (does not describe me at all) to 5 (describes me perfectly). The D5D has accumulated evidence of adequate reliability for the big five dimensions and the reliability calculated using the omega coefficient were adequate for each dimension: emotional stability (ω = .75), introversion (ω = .67), openness (ω = .75), agreeableness (ω = .76), and conscientiousness (ω = .77). Machiavellianism The Machiavellianism Scale (Mach-IV; Christie & Geis, 1970) was used. This scale consists of 20 items which reflect way of thinking and opinions about people and things, providing a measure of Machiavellianism. Participants answer each question on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The reliability calculated using the omega coefficient, for the overall score of the scale was ω = .70. Psychopathy The Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (SRP-III; Williams et al., 2003) was used to assess psychopathy. This self-report questionnaire was designed with 30 items to measure traits of psychopathy in a subclinical population. This instrument assesses 3 dimensions each one consisting of 10 items: (1) erratic lifestyle (e.g., “I am a rebellious person” and “I enjoy taking risks”), (2) callous affect (e.g., “I am often unpleasant towards others” and “I enjoy hurting people I care about”), (3) interpersonal manipulation (e.g., “I am not a cheat” and “I find it easy to manipulate others”). For each of the sentences, participants had to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed. The response scale used was a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The reliability calculated using the Omega coefficient, for the overall score of the scale was ω = .80. Narcissism The narcissism scale of the Personal Styles Questionnaire (Salgado, 2012) was used. This questionnaire consists of 22 items referring to different affirmations in which participants had to indicate whether they considered them true or false. Therefore, this questionnaire had a dichotomous response scale. Some examples from items of this questionnaire are the following: “I prefer to be just one more than to always being the best” and “I find it very difficult to overcome humiliations”. The reliability, calculated with the omega coefficient, in the current sample was ω = .56. Moral Disengagement We used the Propensity to Moral Disengagement Scale (Moore et al., 2012). It is rated on a 24-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A sample item is “It is okay to spread rumours to defend those you care about”. The reliability, calculated with the Omega coefficient, in the current sample was ω = .91. Procedure First, the researchers contacted the heads of 12 prisons in Spain to request participation. All these prisons obtained permission from the Spanish Department of Penitentiary Administration, but only eight agreed to participate. Next, without offering a reward, each prison’s psychologist or social worker invited incarcerated men convicted of economic crime to voluntarily participate. Only participants who displayed basic literacy skills were not affected by psychopathological clinical history and participated in the standard prison activities were considered for inclusion in the study. For the assessment, a questionnaire was collectively administered in classrooms provided by the penitentiary institutions. The sessions were supervised by the prison’s psychological team and the researcher to offer support to the participants in case of doubts or the need for clarifications. This research was approved by the ethics committee (Ref. USC15/2023). Analysis Descriptive and reliability analyses were carried out and the Shapiro-Wilk test was performed to test the normality of the data. Kruskal-Wallis analyses were carried out to analyse whether there were differences in the scores of the variables studied according to the criminal typology of the sample. Associations between variables were tested for by exploring univariate correlations with associated constructs. Hierarchical regressions were tested by exploring the predictive validity of personality and moral disengagement with counterproductive behaviors. All measures showed reliability statistics > .70 or were marginally below that, with the exception of narcissism, whose reliability of .57. This last value can be is due to the fact that narcissism is a multidimensional construct and internal consistency estimates of reliability are typically affected for this characteristic (Hinton et al., 2014). Normality tests tested whether the distribution of data was suitable for parametric statistics. Table 1 reports the mean and standard deviation for the measures used in this study, along with their intercorrelation. Results show significant correlations between overall counterproductive behaviors scores and lower emotional stability, lower agreeableness, lower conscientiousness, higher extraversion, higher psychopathy, and higher moral disengagement. Regarding the different dimensions of counterproductive behavior, the absenteeism dimension was associated with lower scores on agreeableness, and higher scores on extraversion, Machiavellianism, and moral disengagement. The non-compliance-with-rules dimension was associated with lower scores on agreeableness and conscientiousness, while it was associated with higher scores on extraversion, narcissism, and moral disengagement. The behaviors related to the low-effort dimension were associated with higher emotional stability, extraversion, psychopathy, and moral disengagement, while they were associated with lower scores on openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. And, the inappropriate-use-of-resources dimension was associated with higher psychopathy and moral disengagement, while it was associated with lower scores in agreeableness and conscientiousness. Scores on moral disengagement were significantly associated with lower agreeableness, higher extraversion, higher Machiavellianism, higher psychopathy, and higher scores on all dimensions of counterproductive behaviors. Furthermore, the results of the Kruskal-Wallis analysis to examine whether there were differences in the scores of the variables studied according to the criminal typology of the sample showed that there were no significant differences in any of the study variables (p >.05). Table 1 Summary of Means, SDs, and Correlations (Spearman’s rho) between Measured Variables   Note. CWB = overall score of counterproductive work behavior; CWB_A = counterproductive work behaviors regarding absenteeism; CWB_N = counterproductive work behaviors regarding non-compliance of rules; CWB_L = counterproductive work behaviors regarding low effort; CWB_M = counterproductive work behaviors regarding misuse of resources. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. The next set of data results involved multiple regressions. Multiple regression estimates (R, R2, R2adjusted) are typically inflated due to capitalization on chance. It is well known that small sample sizes and the number of predictors affect the size of the observed multiple correlation, so that the more predictors, the greater inflation of R, R2, and R2adjusted. In order to control for this potential inflation, we calculated the statistical estimates of the cross-validated multiple correlation and the cross-validated square multiple correlation using Browne’s (1975) formula, and following the procedures outlined by Lautenschlager (1990) and Yin and Fan (2001) regarding the computation of Wherry’s p4 estimates included in Browne’s formula. Tables 2 and 3 report the results of the multiple regression analyses. Table 2 Predictive models (a, b, c) of counterproductive work behavior by Dark Personality.   Note. CWB = overall score of counterproductive work behaviour. Table 3 Hierarchical Regression Analyses using Big Five and Dark Personality as predictor   Note. CWB = overall score of counterproductive work behavior. The models presented in Tables 2 and 3 examine the predictive capacity of the Big Five personality, dark personality and moral disengagement for predicting counterproductive behavior. According to the first step of Table 3, the Big Five personality model explains only 7% of the variance in counterproductive behavior. This percentage is significantly lower than that obtained in the first model (a) of Table 2, where the dark personality shows a higher predictive capacity, explaining 19% of the variance in these counterproductive behaviors. When considering dark personality and moral disengagement simultaneously in a second model (b) in Table 2, a substantial increase in predictive performance is observed, reaching 26.5% of variance explained for these behaviors. Additionally, a third model (c) is included in Table 2 with the predictor variables of the previous model (b), these being psychopathy and moral disengagement, with which an explained variance of 24.3% is obtained for counterproductive behavior. If only the values of R and R² are considered, including all traits of the dark personality with moral disengagement would be the best option for assessing counterproductive behavior in the sample of felons in this study. However, when applying Browne’s (1975) formula, it is observed that the model that includes psychopathy and moral disengagement has a greater capacity to explain the variance in counterproductive behaviors (22%) than the one that includes Machiavellianism, narcissism, psychopathy and moral disengagement (21%) in similar samples. Finally, to examine the increase in explained variance that dark personality has over the Big Five for counterproductive behaviors, the predictive ability of these variables was assessed in Table 3 in two steps, applying Browne’s (1975) formula in order to generalise the results to larger, and similar samples. The analyses suggest that the combination of psychopathy and moral disengagement increases the predictive capacity of the Big Five predictors of counterproductive behavior (17.5%) and that, furthermore, this increase could also be generalised to similar larger samples (15.4%) when Browne’s (1975) coefficient is used. CWB has become an increasingly popular topic of study among organizational researchers. Most research on CWB has been based on self-report measures and, although useful, this type of assessment can be biased and distorted (Ramos-Villagrasa & Fernández-del-Río, 2023). This has led to a growing demand for alternative approaches that incorporate less biased data into CWB research. Some studies have used ratings from supervisors or co-workers (i.e., other raters) as complements to self-assessments (Berry et al., 2012). However, no research has yet combined CWB self-reports with samples of felons convicted of economic and organizational crime. The aim of this study is to examine the predictive power of personality traits on CWBs by considering both the Five Factor Model and dark personality traits, using a sample of economic crime felons. Although both personality models have been studied separately, few studies have analysed them together to predict CWBs. This study provides a unique, more complete and accurate understanding of the factors that predict counterproductive workplace behaviors by obtaining self-reports of CWB in a sample of felons convicted of economic crimes. Next, we discuss the results found and their implications. Firstly, it could be said that the results found in this study are highly consistent with the theoretical assumptions involved in this research. The overall CWB score has been inversely and significantly associated with the conscientiousness, agreeableness, and emotional stability components of the Big Five personality model, while extraversion has been positively and significantly associated. Previous primary studies included in the meta-analysis by Miao et al. (2023) highlighted these relationships, except for the one found with extraversion in this study. However, this result could be perfectly explained by the notable components of impulsivity and need for stimulation within the classic construct of extraversion (Eysenck, 1977; Squillace et al., 2011), which is also consistent with the results obtained in other studies (Szostek et al., 2022). The overall CWB scores have been primarily associated with the trait of psychopathy, as well as with moral disengagement, a component closely linked to the dark personality profile. This finding is consistent with previous research, which has identified a stronger relationship between psychopathy and moral disengagement in incarcerated adults (Navas et al., 2021a). The results of this study also align with those of Egan et al. (2015), who found that individuals with psychopathic traits were less likely to experience emotions such as shame and guilt due to their elevated levels of moral disengagement, which facilitates the engagement in CWB. However, considering the multidimensional nature of CWB assessed in this study, the relationships between the three dark personality traits and CWBs differ. Absenteeism has been associated with Machiavellianism and moral disengagement, while non-compliance with norms has been associated with narcissism, psychopathy, and moral disengagement. The role of pathologically hypertrophied self-esteem and narcissism in the workplace is relevant in that these characteristics are linked to a lack of self-criticism and excessive confidence in one’s own abilities, which can hinder learning and adaptation in the professional environment (Campbell et al., 2004). Individuals with narcissistic tendencies, due to their distorted self-view, tend to reject constructive criticism and maintain an attitude of superiority that prevents them from accepting corrections or instructions from their superiors and peers (Vazire, 2010). This phenomenon can lead to uninhibited behavior, where organizational boundaries and norms are transgressed due to the belief that norms do not apply to them, creating an adventurous attitude that seeks immediate gratification at the expense of work ethics (McCullough et al., 2003). Furthermore, Machiavellianism is characterized by manipulation, cynicism, and a willingness to lie in order to achieve personal goals, even at the expense of others (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). This behavioral pattern not only affects interpersonal interactions at work but also facilitates absenteeism, as individuals with high Machiavellian traits may use their manipulation skills to justify their absence or failure to meet assigned tasks. For example, they are likely to resort to lies or manipulations to avoid responsibilities or gain personal advantages that allow them to avoid supervision or work effort (Boddy, 2006). The combination of these characteristics contributes to the creation of a toxic work environment, where norms are systematically challenged and absenteeism may increase due to a lack of motivation and the manipulation of work expectations. Secondly, regarding the relationships between dark personality traits, moral disengagement and CWB, different regression models were tested to assess the predictive capacity of these traits together with moral disengagement in the current study sample. Initial multiple regression models showed that the combination of the three dark personality traits, along with moral disengagement, explained a higher percentage of the variance in CWB compared to the model that only considered dark personality traits. This finding suggests that the dark personality profile is strongly linked to the use of cognitive strategies that facilitate moral disengagement, allowing individuals to justify their CWB. In other words, individuals with these traits, characterized by non-normative morality (Egan et al., 2015; Fossati et al., 2014), do not resort to moral disengagement reactively or situationally, but rather internalize it as a deeply ingrained belief. This belief disinhibits their behaviors and facilitates the repetition of such behaviors (Petruccelli et al., 2017b). This finding is particularly relevant for evaluating CWB, as well as for the research field related to dark personality traits and moral disengagement (Lyons, 2019). The strong correlation between these traits and moral disengagement is crucial for assessing risk in individuals who have committed criminal behaviors within organizations. Therefore, it is essential to consider the implications of this personality profile in evaluations, especially with regard to the process of desisting from economic crimes, but also in other processes such as personnel selection. It is reasonable to assume that justifications based on moral disengagement, when used persistently, reduce the assumption of responsibility by those who use them. Furthermore, these justifications can negatively impact their commitment to the organization and have adverse consequences on their job performance (Best et al., 2009). Nevertheless, when we consider not only the percentage of variance explained by the multiple regression model but also Browne’s (1975) coefficient used to estimate the Rcv, it can be seen that the regression model consisting of psychopathy and moral disengagement is the best combination for predicting CWB. When considering the cross-validation estimation of the different models tested for predicting CWBs in relation to dark personality, the significant explanatory and predictive power provided by the inclusion of psychopathy and moral disengagement as predictors in the CWB regression equations is particularly noteworthy. It seems that the cognitive and affective characteristics inherent to high levels of psychopathy explain the strong motivation to commit counterproductive behaviors, while moral disengagement facilitates persistence in these behaviors by eliminating any hint of self-criticism that could trigger inhibitory processes and generate emotions such as remorse, guilt or shame, thus reducing the likelihood of committing this type of CWB. In this way, psychopathy and moral disengagement form a closed feedback loop that reinforces counterproductive behaviors, significantly reducing the likelihood of experiencing distress from the impact of these behaviors on individual performance, interpersonal relationships, and organization. Consequently, the presence of psychopathy and moral disengagement in the employees evaluated could increase the incidence of counterproductive behaviors, such as absenteeism, sabotage, or lack of commitment to tasks (Best et al., 2009). Thirdly, it is important to highlight the remarkable variance explained by psychopathy and moral disengagement, which considerably exceeds the variance explained by the Big Five model when both personality models are considered together to predict CWB. The results obtained clearly show that psychopathy and moral disengagement have a greater explanatory capacity with respect to self-reported CWB, compared to generic personality indicators. Thus, it seems that, as the nature of the predictor becomes more in line with the type of behaviors to be predicted, the relationship between both factors grows significantly. In any case, we believe that there should not be a confrontation between ‘predictive models’, since, to a large extent, the traits that make up the dark personality can be interpreted as the reverse of certain traits and/or facets of the Big Five model. Related to the above, the considerable explanatory power of constructs and instruments derived from Personality Psychology to establish relevant associations and predictions with the self-reported CWB of officially recorded economic crime offenders stands out. The inclusion of moral disengagement in the model caused facets of the Big Five model and psychopathy to lose significant influence, probably because in part these traits underlie moral disengagement. These results suggest that, although moral disengagement is associated with a variety of darker personality traits, it also captures aspects of unpleasantness that are not assessed by other measures. In this sense, our results suggest that assessments of antisocial cognition complement dispositional measures of darker personality in predicting antisocial attitudes and behaviors in organizational settings. Finally, it should be noted that to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study following the recommendations of Berry et al. (2012) to use a multi-method approach in the assessment of counterproductive behaviors that uses officially recorded and punished records of economic crime in organizations. This multi-method approach significantly improves the accuracy and validity of the results by reducing the limitations of individual methods. Self-reports, for example, may be biased by social desirability, leading employees to minimize their negative behaviors. By integrating different sources of information, such as officially sanctioned criminal records, a more complete and objective view of counterproductive behaviors is obtained, thus mitigating these biases. In addition, this approach facilitates the detection of a variety of behaviors, from misinformation to sabotage, that may not be evident with a single method. By considering multiple perspectives, it more effectively identifies the cognitive and personality characteristics that may underlie disruptive behaviors in organizational contexts. Practical Implications Measures of the Big Five personality dimensions are frequently used to make hiring decisions due to their remarkable validity for predicting job performance (particularly, task and citizenship performance). This is especially the case of quasi-ipsative forced-choice (QIFC) personality inventories (Salgado, 2017; Salgado & Tauriz, 2014), which are also very robust against faking (Martinez & Salgado, 2021; Martínez et al., 2022; Salgado & Lado, 2018). Due to the multidimensional nature of job performance, mainly consisting of four dimensions (i.e., task, citizenship, innovative and counterproductive performance), the incorporation of dark personality and moral disengagement assessment in selection processes can be a useful recommendation to predict and prevent counterproductive behaviors that negatively affect the organization. Through psychometric tools, structured interviews, or gamified based assessment (Ramos-Villagrasa & Fernández-del-Río, 2023), organizations can identify traits associated with the dark triad, such as psychopathy, Machiavellianism and narcissism, which are often linked to manipulative behaviors, lack of empathy and ethically questionable decision making. These personality traits can predict destructive team attitudes, generate interpersonal conflict and foster unethical work practices. Furthermore, the results of this study highlight the importance of assessing moral disengagement in the organizational context, as it involves cognitive mechanisms that justify unethical behavior. Thus, it is possible to identify individuals who, despite having an apparently appropriate personality, may distort their perception of right and wrong based on personal interests. Incorporating these factors into selection processes allows organizations to adopt more informed decisions, avoiding the hiring of individuals who, due to their lack of ethics or tendency to manipulate, may generate counterproductive behaviors such as sabotage, misinformation, absenteeism or non-compliance with rules. Likewise, the findings of this study can be useful for designing training and development programs focused on conflict management and teambuilding, promoting the reconfiguration of attitudes towards ethics, cooperation and respect within the company. The cognitive mechanisms involved in moral disengagement are more flexible and susceptible to change than certain personality characteristics, so organizations have a greater opportunity to intervene in a preventive manner. Promoting self-regulation and ethical decision-making in training will contribute to strengthening the organizational culture, improving the workplace climate and reducing the risk of counterproductive behaviors in the long-term. Limitations and Future Directions There are limitations to this research, as in any study, which should be addressed. First, the sample size was small, which may limit the generalizability of the results. This is a common limitation in research using samples of felons with officially recorded and punished economic crime given the difficult accessibility of such samples. We consider that, despite the small sample size, our research was significant, deepening the relationship between dark personality and moral disengagement found in previous studies (Egan et al., 2015) with samples of employees. Additionally, it can be highlighted that individuals who have committed economic crimes are not inherently different from those in the general population. Including the comparison of economic crime felons and employees in future research could help reduce the dehumanizing perceptions that often arise from stereotypes, while also exploring the relationships between dark personality traits and moral disengagement in both samples. Future research could explore how the relationships of dark personality and moral disengagement play out in both samples. Second, a cross-sectional study design was used, so causal relationships could not be tested and may generate substantially biased estimates compared to analyses from longitudinal research (Maxwell & Cole, 2007). The results of this manuscript only show the interdependence of the variables assessed at a specific point in time. Therefore, future research should use longitudinal designs to clarify whether moral disengagement affects psychopathy or whether psychopathy affects moral disengagement. Third, the current sample included felons from Spain, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other cultural contexts. Cultural differences in criminal codes and behaviors officially punished in the workplace may influence how employees perceive and respond to organizational politics, intragroup conflict, support, and power. Therefore, it is possible that the observed profiles may not reflect the experiences of felons from other cultural contexts. Thus, subsequent research could compare economic crime felons, but with diverse cultural backgrounds. Conclusions This study’s contributions lie in its exploration of the CWB and its relationships with the Big Five personality dimensions, dark personality traits, and moral disengagement. By incorporating a multi-method approach to assessing these factors (e.g., Berry et al., 2012), we find that dark personality traits, especially psychopathy, are strongly related to moral disengagement, which in turn predicts unethical behaviors in the workplace. Our study supports previous research on the role of personality in shaping workplace behavior and provides valuable insights for managers and HR professionals seeking to mitigate CWB. We suggest that, rather than focusing solely on personality traits, organizations can benefit from addressing cognitive mechanisms like moral disengagement through tailored interventions in training programs. This approach could help create a more ethical and productive work environment. Further research should explore how these dynamics manifest in diverse cultural contexts and extend the findings to a wider range of industries and employee profiles. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Note Crimes classified under any of the categories included in the Spanish Penal Code in Titles XIII, XIII bis, XIV, XV, XV bis, and Title XVI. Cite this article as: Navas, M. P., París, T., Sobral, J., & Moscoso, S. (2025). The Big Five, dark personality, moral disengagement and counterproductive behavior at work. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 41(1), 27-38. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2025a4 References |

Cite this article as: Navas, M. P., París, T., Sobral, J., & Moscoso, S. (2025). The Big Five, Dark Personality, Moral Disengagement and Counterproductive Behavior at Work. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 41(1), 27 - 38. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2025a4

Correspondence: mnavas@unizar.es (M. Patricia Navas).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS