From Organisation’s Affective Commitment to Employees’ Extra Role Behaviour: A Sequential Effect

[Del compromiso afectivo de la empresa al comportamiento extra-rol de los empleados: un efecto secuencial]

Joaquín García-Cruz & Ramón Valle-Cabrera

Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Seville, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2025a7

Received 21 April 2025, Accepted 14 July 2025

Abstract

The aim of this study is to examine the association between organisation’s affective commitment and employees’ organisational citizenship behaviour. Considering that this association could be indirect, we propose the AMO [abilities, motivation, and opportunities] model and perceived organisational support as mediator variables. Using a sample of 102 HR managers and 306 trade union representatives of Spanish hotels, we found no direct but indirect association, with two sequential mediation effects: (1) the AMO model mediates between the organisation’s affective commitment and perceived organisational support; and (2) the perceived organisational support mediates between the AMO model and organisational citizenship behaviour. In short, organisation’s affective commitment is not sufficient alone to drive employee organisational citizenship behaviour. Organisations must translate their affective commitment into positive actions (via the AMO model) and these actions must be actually perceived by employees.

Resumen

El objetivo de este estudio consiste en analizar la asociación entre el compromiso afectivo de la organización y el comportamiento ciudadano organizativo. Considerando que esta asociación pudiera ser indirecta, proponemos el modelo HMO [habilidades, motivación y oportunidades] y la percepción de apoyo de la empresa como variables mediadoras. Utilizando una muestra de 102 directores de RRHH y 306 representantes sindicales de hoteles españoles, observamos que esta asociación no es directa sino indirecta y se produce a través de dos efectos de mediación secuenciales: (1) el modelo HMO media entre el compromiso afectivo de la organización y la percepción de apoyo organizativo y (2) la percepción de apoyo de la organización media entre el modelo HMO y el comportamiento ciudadano organizativo. En resumen, el compromiso afectivo de la organización por sí solo no es suficiente para impulsar el comportamiento ciudadano organizativo. Las empresas deben traducir su compromiso afectivo en acciones positivas (a través del modelo HMO), que sean realmente percibidas por los empleados.

Palabras clave

Compromiso afectivo de la organización, Comportamiento de civismo en la empresa, Modelo HMO, Percepción de apoyo en la empresaKeywords

Organisation‚Äôs affective commitment, Organisational citizenship behaviour, AMO model, Perceived organisational supportCite this article as: García-Cruz, J. & Valle-Cabrera, R. (2025). From Organisation‚Äôs Affective Commitment to Employees‚Äô Extra Role Behaviour: A Sequential Effect. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 41(2), 65 - 73. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2025a7

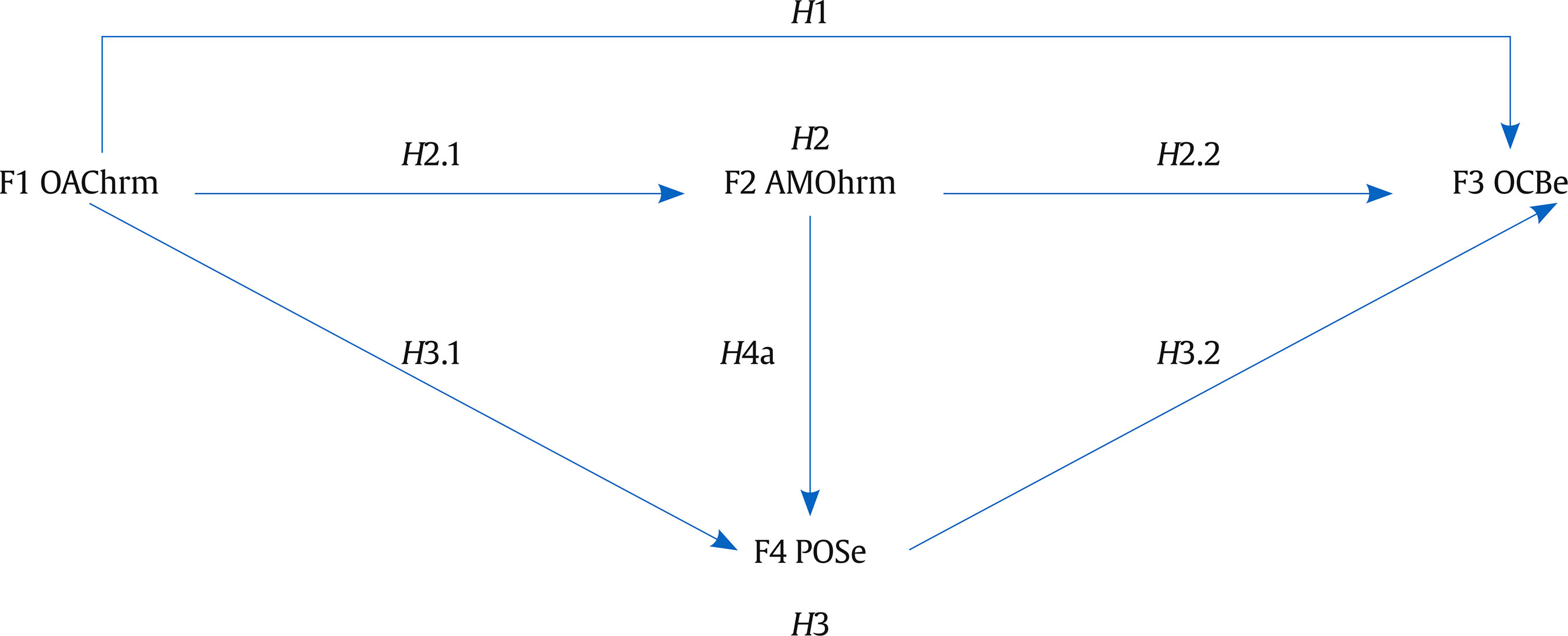

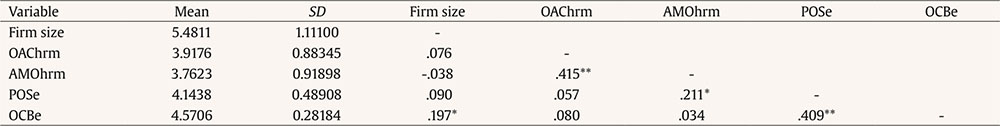

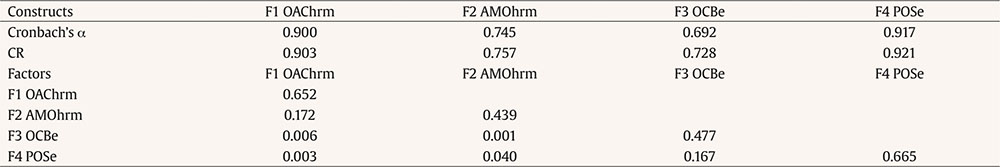

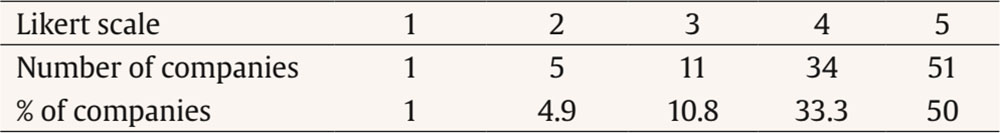

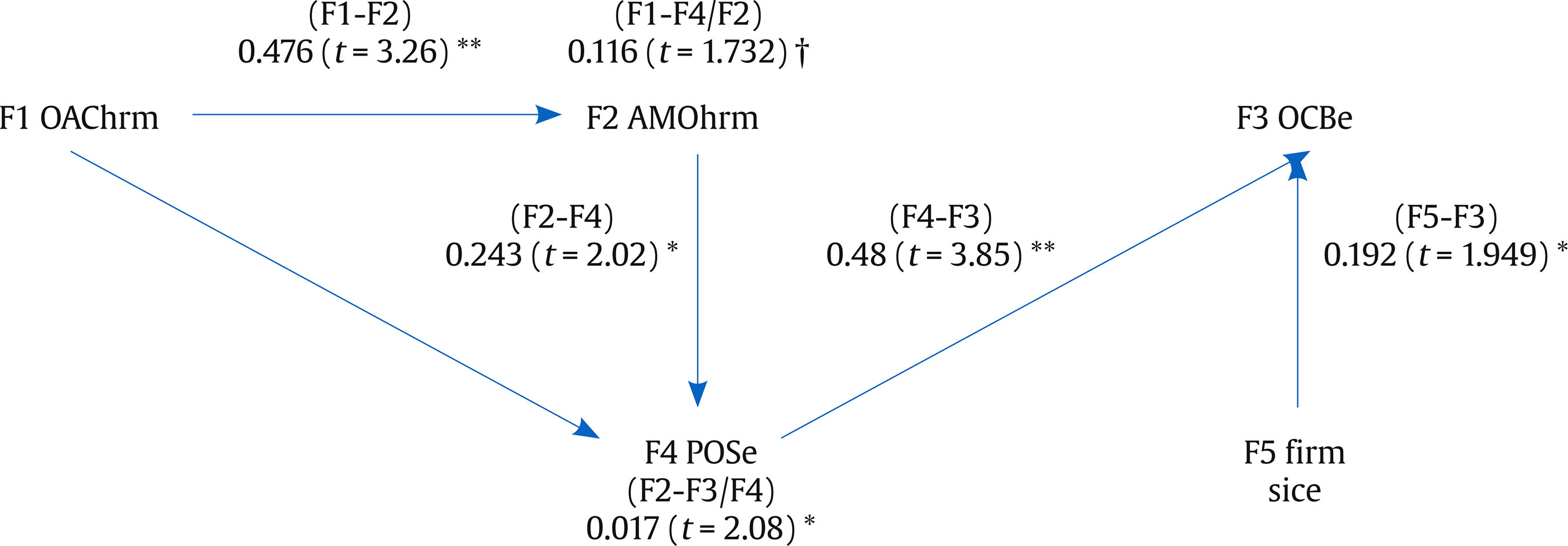

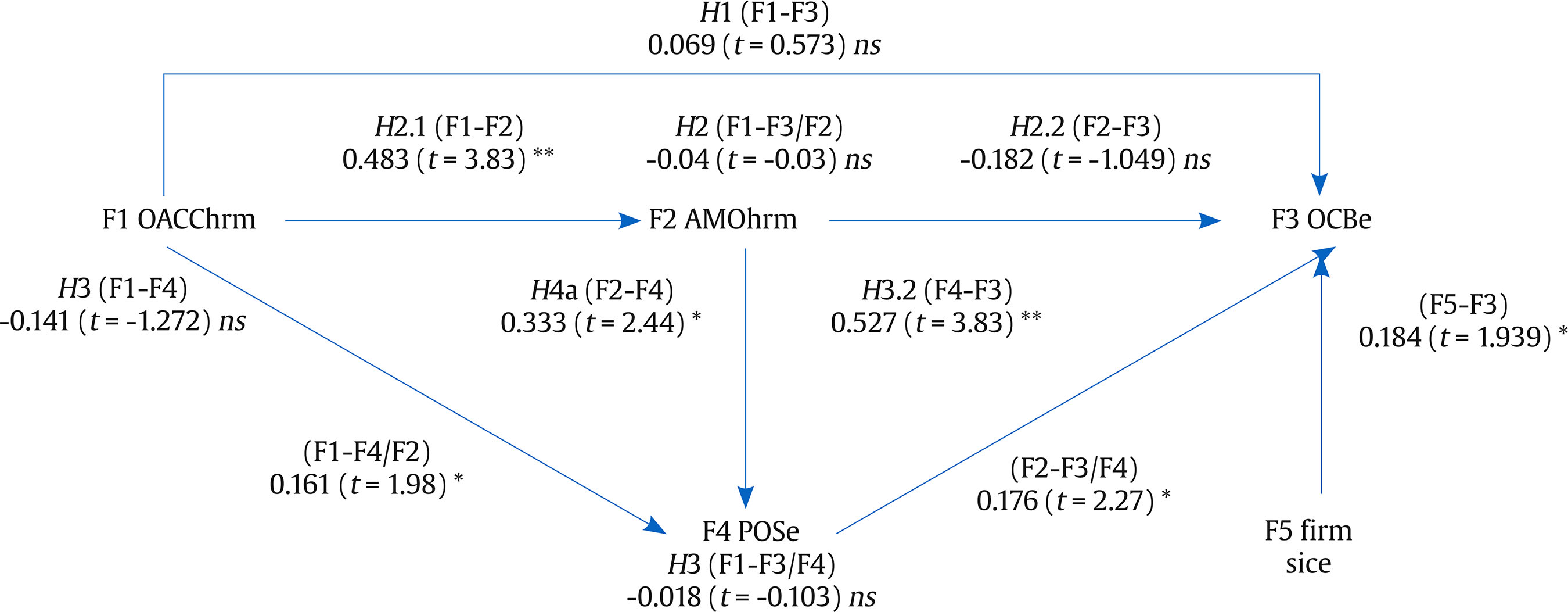

Correspondence: jgarcru@upo.es (J. García-Cruz)Literature about "organisational affective commitment" paradoxically examines commitment from the employees’ perspective (Lado et al., 2023; Herscovitch & Meyer, 2002; Odoardi et al., 2019). Perhaps, it would have been more coherent to call it “employees’ effective commitment”, since what is actually being examined is the affective commitment of employees. In this paper, we examine affective commitment from the perspective of the organisation, that is, we study an organisation’s commitment towards its employees. From this view, it makes sense to call it “organisation’s affective commitment.” Considering the current socio-economic context in which companies operate, after the COVID-19 pandemic we are enjoying a period of recovery and economic growth. In this context, organisation’s commitment to their employees becomes particularly relevant. The society expects and demands organisations to share the benefit of recovery with their employees. The question is whether or not companies are willing to do it. The literature on sustainability, grounded in the institutional theory (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), suggests that institutions compel companies to assume responsibilities with their stakeholders (Dubey et al., 2019). However, in practice, not all companies respond with the same intensity to institutional pressures. In fact, some companies are orientated towards sustainability while others move away from this approach. It seems that the ability of the institutional theory to explain companies’ behaviour toward sustainability is limited. Lee (2011) justifies this duality in companies’ behaviour, stating that organisations can easily ignore institutional pressures and limit themselves to complying with legal requirements. After all, being willing to go beyond the law’s demands is a “voluntary” choice. In an attempt to address this dilemma, we try to complement the institutional theory with the social exchange theory (SET) (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano & Mitchel, 2005). We suggest that companies that are affectively committed engage in positive behaviours towards their employees, which can elicit reciprocal positive behaviours from them. Several questions arise from this suggestion. First, can companies truly engage affectively with their employees? Second, what is exchanged? Specifically, what do companies receive in return for their affective commitment? Lastly, how does this exchange occur, that is, does it occur automatically or are intermediate transmission mechanisms required? To answer these questions, we reviewed the existing literature on “organisations’ commitment to employees” and found several limitations. First, this construct has usually been defined and assessed only through the economic dimension (Nguyen & Teo, 2018; Roca-Puig et al., 2007; Roca-Puig et al., 2012; Torka et al., 2005), excluding the affective dimension from the analyses. The second limitation is related to a construct’s evaluations. Previous studies often assessed the companies’ commitment indirectly through subrogates, such as the extent to which the organisation provides compensation fairness, profit-sharing, investments in progressive human resource management [HRM] practices, and so on (Miller & Lee, 2001; Muse et al., 2005; Nguyen & Teo, 2018; Roca-Puig et al., 2007; Roca-Puig et al., 2012). We suggest three specific objectives to address these limitations and answer the three questions set out. First, we aim to test if organisations can commit affectively by evaluating an organisation’s degree of affective commitment to employees. To assess this affective dimension of the commitment, we follow García-Cruz and Valle-Cabrera’s (2021) model focusing. Second, to figure out what organisations can get from their employees in exchange for their affective commitment. We suggest that companies could expect extra-role behaviour from employees when they commit affectively to them. According to the Attribution Theory (AT) (Fiske & Taylor, 1991), employees expect benevolent behaviours from organisations that go beyond rational or economic calculation. In this regard, and consistent with the SET, employees seeking to balance their relationship with their company are also willing to go beyond of in-role behaviour by performing organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB) (P. M. Podsakoff et al., 2000). Third, since an organisation’s affective commitment (OAC) is an affective attitude of the organisation, we aim to determine whether OAC is directly passed on to the employees or if organisational transmission mechanisms are required. In relation to the last objective, the literature highlights that the usual mechanism for transforming an organisation’s intentions (commitment) into actions is the HRM system (HRMS) (Beer et al., 2015; Parke et al., 2021). Paauwe and Boselie (2004) noted that one of an organisation’s major assets is how employees are treated. We propose the AMO [abilities, motivation, and opportunities] model as an appropriate HRMS to turn companies’ affective commitment into actions (Appelbaum et al., 2000). Thus, if an organisation is affectively committed to its employees, the HR managers should: (1) design an HRMS that provides employees with the skills and knowledge they need to perform their jobs with efficiency (Abilities); (2) motivate them by acknowledging their results at work through incentive systems (Motivation); and (3) offer them opportunities for participation and involvement (Opportunities). Additionally, we suggest perceived organisational support (POS) can explain the link between OCB and OAC. According to SET, employees engage in organisational extra-role behaviours (OCBs) when they perceive support from the organisation (POS) (Chênevert et al., 2015). Furthermore, employees will feel supported and be more likely to exhibit OCB when they perceive the organisation as being affectively committed to them. Lastly, we suggest that a sequential double mediation by HRMS and POS is necessary to explain OCB in relation to OAC. To justify this mediation approach, we start from the established HRMS-POS relationship (Mayes et al., 2017; Rubel et al., 2021). In this context, we suggest OAC as an antecedent of HRMS, because it is an organisational attitude that determines HRMS (AMO model) configuration. Additionally, we posit OCB as a consequence of POS. We suggest that employees will perform OCB when they have actually perceived support from the organization (POS), which occurs when they are managed through an HRMS that enables a high level of performance (AMO model). This study makes several contributions to the literature. First, the study directly evaluates OAC as an affective organisational attitude (García-Cruz & Valle-Cabrera, 2021). Second, the study examines OAC’s direct and indirect effect on OCB through HRMS and POS. Finally, the study contributes to the strategic HR management literature by proposing the AMO model (Appelbaum et al., 2000) as a suitable HRMS to reflect an organisation’s affective commitment towards their employees. Theoretical Framework The Organisation’s Affective Commitment as an Antecedent of the Organisational Citizenship Behaviour Organisation’s commitment is a construct that was defined by García-Cruz and Valle-Cabrera (2021) as an organisation’s attitude that defines the relationship the organisation has with its employees. Likewise, the construct explains an organisation’s decision to extend the employment relationship with employees. This definition identifies three dimensions based on the reasons for extending the employment relationship: the employer (1) needs to do so (employer’s continuance commitment), (2) wants to do so (employer’s affective commitment), or (3) feels obliged (employer’s normative commitment) to do so. Previous studies have assumed an organisation’s commitment construct is one-dimensional and of a rational/economic nature (Nguyen & Teo, 2018; Roca-Puig et al., 2007; Roca-Puig et al., 2012), neglecting the affective dimension. In contrast, we suggest that the affective dimension should be as important as the economic one. Our literature review presents several explanations for this suggestion. The first one comes from the literature on corporate social responsibility (CSR) and HR sustainability (Kramar, 2014). This literature shows that companies are willing to act for the benefit of their employees (and other stakeholders) by going beyond what a simple cost-benefit (economic) analysis might advise. Similarly, literature on family businesses defines “socio-emotional wealth” as a stock that these companies choose to preserve to meet their emotional needs, even when this implies fewer benefits (Gomez-Mejía et al., 2011). Additionally, García-Cruz and Valle-Cabrera (2021) demonstrated that the affective dimension of the construct can function as an autonomous variable. Once pointed out that the affective dimension of an organisation’s commitment to its employees has its own entity, the question is: can an organisation’s affective commitment (OAC) activate organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB)? According to the Attribution Theory (AT) (Fiske & Taylor, 1991), when companies commit affectively to their employees, they expect organisations to exhibit behaviours that go beyond what a rational or economic calculation might advise. Basing on the SET (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano & Mitchel, 2005), we suggest that an organisation’s commitment to its employees is part of a social exchange process in which the employees repay the organisation’s commitment by performing extra-role behaviour. For this relationship to occur, OAC must be considered an exchangeable resource that can be offered to employees in return for their extra-role behaviour. Aselage and Eisenberger (2003) identified that the resources exchanged between employers and employees may be impersonal, such as the provision of information or money. However, they may also be considered socio-emotional resources, such as the communication of caring or respect. OAC is defined as an organisation’s positive attitude towards employees (García-Cruz & Valle-Cabrera, 2021), which is a display of affection and consideration towards them. So, we suggest that OAC could be considered as a socio-emotional resource. Therefore, according to SET, we consider that OAC can be offered to employees in exchange for extra-role behaviour (OCB). Thus, the greater the OAC, the stronger the employees’ willingness to engage in OCB. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis: H1: An organisation’s affective commitment (OAC) is positively associated with their employees’ willingness to develop organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB). The HRM System (AMO Model) as a Mediator Variable between Organisation’s Affective Commitment and Organisational Citizenship Behaviour The revised literature on organisations’ commitment reveals that this construct makes employees more conscientious in performing their job responsibilities. It engenders a sense of involvement with the company, encourages greater initiative and innovation, stimulates more company ‘citizenship’ behaviour among employees, and prepares them to exceed their job requirements (Eisenberger et al., 2001; Miller & Lee, 2001; Shore & Wayne, 1993). These arguments support the association between HRMS and OCB. We propose to introduce OAC in this association in such a way that HRMS mediates between OAC and OCB. We think that the HRMS’s effectiveness will depend on the organisation’s commitment and, in turn, the willingness of employees to perform extra-role behaviours (OCB) will depend on the HRMS. Thus, if an organisation is affectively committed to its employees, HR managers will shape a different HRM than one driven by continuity or normative commitment (García-Cruz & Valle-Cabrera, 2021). We also suggest that employees, to perform extra-role behaviours, need more than just oral demonstrations of the organisation’s attitude; they need specific actions (HRM practices) that truly persuade them of the organisation’s intentions. We suggest that the HRMS best reflecting the effects of OAC on OCB is the AMO model (Appelbaum et al., 2000). This model focuses on three aspects of employee performance: employees’ development by means of improvement of their skills (“abilities”), reward systems linked to results (“motivation”), and “opportunities” for participation (Beltrán-Martín & Bou-Llusar, 2018). Practices that develop abilities (A) include the exhaustive recruitment of new employees, rigorous candidate selection processes and extensive training. Practices for motivation (M) would include directing employees’ efforts towards their work goals and providing the necessary incentives for them to become involved in achieving high levels of performance and internal promotion. Finally, practices that create opportunities (O) to participate are based on delegating responsibility, facilitating employee participation, and communicating with employees (Beltrán-Martín & Bou-Llusar, 2018; Gardner et al., 2011). Considering these practices, we suggest that an organisation committed to its employees should adopt the AMO model to favour the development of extra-role behaviours (OCB), as substantiated by previous research (Beer et al., 2015; Grund & Titz, 2022; Kehoe & Wright, 2013; Salas-Vallina et al., 2021). Considering the role played by practices associated with the AMO model, we propose H2 hypotheses: H2: The AMO model mediates the relationship between organisation’s affective commitment (OAC) and organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB). H2.1: Organisation’s affective commitment (OAC) is positively related to the AMO model. H2.2: The AMO model is positively related to OCB. Perceived Organisational Support as a Mediator Variable between An Organisation’s Affective Commitment and Organisational Citizenship Behaviour Perceived Organisational Support (POS) refers to the degree to which employees believe that their organization values their contributions and cares about their wellbeing (Eisenberger et al., 1986). The focus of POS lies in the idea that when employees feel supported by their organization they are more likely to be engaged, perform well, and stay longer. Basing on Eisenberger et al. (2001), we suggest that when employees feel supported by an organisation (POS), they engage in OCB (Alshaabani et al., 2021). Additionally, we suggest that employees view an organisation’s affective commitment (OAC) as a sign of the organisation’s support. Thus, we propose perceived organisational support (POS) as a variable through which OAC exhibits itself and determines OCB. To explain this mediation effect, we applied SET and AT as theoretical frameworks. SET is a powerful social convention that posits that employees reciprocate employers’ inducements by positive behaviours (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano & Mitchel, 2005). Therefore, OAC makes employees feel supported by the organisation, to which they respond by developing OCB. According to AT (Fiske & Taylor, 1991) and the anthropomorphisation process (Coyle-Shapiro & Shore, 2007), OAC makes employees attribute positive personal intentions to the organisations, enhancing their sense of support. Thus, we believe that OAC reports employees about the degree to which the organisation intends to care about their well-being, considers their goals and opinions, and shows interest in them. Therefore, by suggesting that employees feel supported (POS) when the organisation is affectively committed to them (OAC), we reveal that OAC is a POS antecedent. Considering the arguments and based on organisational support theory (Aselage & Eisenberger, 2003), we can assume that employees are willing to increase their efforts to the extent that they perceive that the organisation can reciprocate with desirable impersonal and socioemotional resources. Therefore, when employees perceive OAC, they feel supported and respond by performing extra-role behaviours (OCB). Cropanzano and Mitchell (2005) postulated that POS benefits are often understood reciprocally. Roca-Puig et al. (2012) indicated that employees are more likely to develop positive affective attachments to their employer when they feel that their organisation considers their needs and cares about their well-being. Alshaabani et al. (2021) researched the impact of POS on OCB during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hungary and concluded that POS was positively associated with OCB. Shore and Wayne (1993) highlighted that employees who feel that they have been well supported by their organisations tend to reciprocate this treatment by performing better and engaging more readily in citizenship behaviour. Therefore, following SET, we predict that an organisation’s commitment to its employees will have a positive impact on employees’ POS and, consequently, on employees’ behaviour (OCB). Based on these ideas, we propose the following hypotheses: H3: Perceived organisational support (POS) mediates the relationship between an organisation’s affective commitment (OAC) and organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB). H3.1: OAC is positively related to POS. H3.2: POS is positively related to OCB. Organisation’s Affective Commitment and Organisational Citizenship Behaviour: A Relationship Sequentially Mediated by HRM System (AMO Model) and Perceived Organisational Support Finally, we propose that organisation’s affective commitment (OAC) explains OCB through the sequential mediation of HRMS (AMO model) and POS. For employees to reciprocate the company’s commitment, it must materialise in HRM practices and, above all, these practices must be perceived by employees. In other words, we are suggesting a double mediation effect which can be summarised in three sequential direct steps: (1) OAC determines the configuration of HRMS (AMO model), (2) the practices associated with the AMO model explain the perceived organisational support (POS), and (3) POS influences the extra role behaviours (OCB). The relationships between the OAC-AMO model and POS-OCB have already been justified in hypotheses H2.1 and H3.2; only the association between the AMO model and POS remains to be justified. In this vein, the literature has shown that favourable working conditions are positively related to POS. Thus, developmental experiences that allow employees to expand their skills, autonomy in the way jobs are performed, and visibility by and recognition from upper-level management are practices that generate POS (Wayne et al., 2002). Furthermore, the literature highlights how certain HRM practices are considered antecedents of POS. Mayes et al. (2017) concluded that hiring, training, and compensation practices predict POS. Similarly, Arefin et al. (2015) found that when HRM practices are appropriately implemented, they create a positive impression of organisational support among employees. Bowen and Ostroff (2004) emphasised that actual investment in the HR of a firm is effective only when employees perceive that their company is investing in them. Rubel et al. (2021) suggested that POS mediates the relationship between high-performance work practices and medical professionals’ work outcomes. Detnakarin and Rurkkhum (2019) examined the moderating effect of POS on the relationship between human resource development practices and OCB in hotels in Thailand. The relationship was stronger for employees with high POS. The considered arguments allowed us to set our last hypotheses. H4: The effects of an organisation’s affective commitment (OAC) on organisation citizenship behaviour (OCB) are mediated sequentially by the AMO model and by perceived organisational support (POS). H4a: The AMO model is positively associated with POS. Figure 1 combines all the relationships and hypotheses raised. Figure 1 Theoretical Model.   Note. Organisation’s affective commitment assessed by HR managers (OAChrm); HRM system assessed by HR managers (AMOhrm model); perceived organisational support assessed by employees (POSe); organisational citizenship behaviour assessed by employees (OCBe). Sample and Data Collection The study population is recruited from the Spanish hospitality industry. We decided to analyse this industry for two reasons. First, it is important to the Spanish economy (Briedenhann & Wickens, 2004). Data from INE (2022) suggest that in 2018, it represented 12.2% of the national GDP and 12.8% of employment; because of the pandemic, in 2020, these percentages decreased to 5.5% and 11.8%, respectively. Second, the dependent variable (OCB) is of particular importance in the hospitality industry because hotel employees must be willing to go beyond their formal obligations to achieve customer satisfaction (Sun et al., 2007). Three criteria were adopted to select companies from the target population: (1) being a hotel with at least four stars, (2) having an HRM department or equivalent, and (3) having 50 or more employees, to focus on those companies that were most likely to have a formally established HRM system (HRMS). We used the Sistema de Análisis de Balances Ibéricos [Iberian Balance Sheet Analysis System] (SABI) database to identify companies that fulfilled the three requirements outlined above. Our research team contacted each company to verify that they fulfilled all three requirements. This enabled us to gather a target population of 401 hotels. We received information from 102 hotels, which represents 25.43% of the target population. We collected and handled data from the HR managers and trade union representatives of these 102 hotels. The head of the HR department and three trade unionists responded from each hotel (102 HR managers and 306 trade union representatives). We decided to survey HR managers because they have a general vision of the HRM department and are responsible for designing the company’s HRM system (HRMS). Accordingly, we consider them as key informants concerning the commitment that the organisation claims to have regarding employees and the design of the HRMS (Arthur & Boyles, 2007). To obtain information about employees, given that we could not reach all of them, we decided to contact the union representatives of the companies (three for each hotel) to obtain the perception of all the employees whom they represented. The largest union in Spain was contacted. Unions play a crucial role in the Spanish economy. They oversee the collective bargaining processes between union and company representatives regarding work schedules and productivity, training, careers, salaries and compensation, overtime remuneration, holidays, and work-life balance (Estatuto de los Trabajadores, Articles 62 and 63, Law 36/2011). In summary, we requested information from the HR manager (‘hrm’) concerning organisations’ affective commitment (OAChrm) and the HRMS (AMOhrm model). On the other hand, we asked for information from trade union representatives (employees, ‘e’) concerning perceived organisational support (POSe) and organisational citizenship behaviour (OCBe). Measures To build the questionnaire, we adapted scales that were validated. All items were measured using a Likert scale from one (totally disagree) to five (totally agree). We used dependent, independent, control, and mediating variables. The dependent variable is organisational citizenship behaviour (OCBe) and the independent variable was organisation’s affective commitment (OAChrm). The mediating variables were the AMOhrm model and perceived organisational support (POSe). We used firm size as a control variable. To avoid common method bias problems, employees assessed the dependent variable (OCBe), while HR managers evaluated the independent variable (OAChrm) (N. P Podsakoff et al., 2013; P. M. Podsakoff et al., 2003). Regarding the mediating variables, the AMO model is measured from the perspective of HR managers (AMOhrm) because they are responsible for designing the HRM system (HRMS). Given that POS refers to employees’ perceptions of organisational support, we consider employees to be key informants in reporting on this variable (Arthur & Boyles, 2007). To measure the dependent variable, organisational citizenship behaviour, we used Kehoe and Wright’s (2013) six-item scale from the employees’ perspective (OCBe). With this scale we try to capture the willingness of employees to perform extra role behaviours. The independent variable, OAC perceived by HR managers (OAChrm), was measured using the five-items scale recently developed by García-Cruz and Valle-Cabrera (2021). This scale is useful to collect the attitude of the organisation toward employees. Regarding the mediating variables, POS was measured from employees’ perspective using Rhoades et al.’s (2001) scale of eight-item. The POS scale tries to gather from the employees’ perspective the degree to which the organisation cares about the wellbeing of the employees and the degree to which employees believe that the organisation values their contribution. The AMOhrm model was measured by adapting the scale developed by Gardner et al. (2011) with 18 items for HR managers. Of these 18 indicators, 5 evaluate the degree to which the organization provides its employees with the knowledge necessary to execute their jobs with efficacy (ability). The next 6 items measure how the organisation motivates and incentives its employees (motivation). And the final 7 items evaluate the opportunities for participation and involvement that the organization provides to its employees (opportunities). Finally, we operationalize “firm size” as a control variable using the natural log value of total employment. Aggregation Analysis For the scales measured by employees (OCBe and POSe), we obtained individual responses from three employee union representatives per hotel. We grouped these responses into aggregate measurements that represented OCBe and POSe for each hotel. To ensure the appropriateness of the aggregation, we conducted an inter-rater agreement analysis using the LeBreton and Senter (2008) formula. The results of this aggregation (rwg = .940 > .70) revealed a high level of agreement among the three employees regarding their OCBe perceptions. Similar results are obtained for POSe (rwg = .876, > .70). In addition, we calculated group-size-corrected intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) using SPSS Statistics 29.0 software. Thus, for OCBe, ICC1 = .302 and ICC2 = .722 (Glick, 1985). The results of the F-test (3.591, p < .01) indicated that data aggregation was justified. Similar results were found for POSe, with ICC1 = .49 and ICC2 = .885 (F test of 8.68, p < .01). All the results obtained were within acceptable limits (James et al., 1993). To check for non-response bias between the target population (401 hotels) and the sample that was eventually analysed (102 hotels), we conducted an equality means test for independent samples regarding the number of employees. The results obtained (t = -1.018, p = .311 > .05) supported the conclusion that there is no problem of non-response bias in our data due to company size. Strategy of Data Analyses We followed Anderson and Gerbing’s (1988) two-step approach to check the reliability and validity of the measurement model and test the hypothesized structural model. To perform these analyses, we used structural equation modeling (SEM) with EQS 6.3. software. a) Results of the reliability and validity of scales. First of all, we performed individual confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for each factor. Once every factor had been fitted, we calculated the mean and standard deviation of each variable as well as its correlations (Table 1). Table 1 Mean, Standard Deviation, and Correlations between Variables   Note. Firm size = control variable. Variables measured from the HR manager’ perspective (“hrm”) = organisation’s affective commitment (OAChrm); AMOhrm model. Variables measured from the employees’ perspective (“e”): perceived organisational support (POSe); organisational citizenships behaviour (OCBe). *p < .05, **p < .01 To test composite reliability, discriminant validity, and convergent validity, we examined the complete measure model (CMM), which is composed of all aforementioned factors. The CMM showed the following fit: Satorra Bentler: χ2SB = 146.512, df = 144; pv = .426; Bentler-Bonett non-normed fit index = .996; comparative fit index = .997; Bollen’s fit index = .997; root mean-square error of approximation = .013. To test the convergent validity, we used the average variance extracted (AVE). According to Fornell and Larcker (1981), AVE measures the amount of variance captured by a construct in relation to the amount of variance due to measurement error. Our results revealed that the OAChrm (.652) and POSe (0.652) factors showed AVE higher than .50 (Table 2). Table 2 Construct Reliability, Convergent Validity, and Discriminant Validity   Note. CR = composite reliability. Diagonal elements (in bold) are the average variance extracted (AVE). Under AVE are the square correlations among constructs. F1 Organisation’s affective commitment (OAChrm); F2 AMOhrm model; F3 perceived organisational support (POSe); F4 organisational citizenships behaviour (OCBe). Following Fornell and Larcker (1981) to confirm the discriminant validity, we compared the AVE of each factor with the square correlation between factors. In all cases, the AVE was far greater than the square correlations (Table 2). To assess reliability, we report both composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha. Specifically, composite reliability measures multi-item internal consistency by evaluating how well the items within a scale correlate with each other to measure the same underlying construct. Although composite reliability is often preferred in the case of structural equation modeling or confirmatory factor analysis (as used here), we report both for completeness. All the values of the composite reliability (CR) were higher than .70 (Hair, et al., 2010). Cronbach’s alpha values were also similar. In short, the results allow us to confirm that our scales are reliable (Table 2). b) Results of the hypotheses test. Before describing the results obtained with the hypotheses test, we highlight other results related to the primary objectives set out in the paper, that is, to determine the level of affective commitment that companies have with their employees as assessed by HR managers (OAChrm). As shown in Table 3, the statistical analysis revealed that 83.33% of HR managers evaluated OAChrms at 4 points or more. Based on this information, we conclude that the HR managers surveyed perceive the organisations analysed as affectively committed to their employees. Table 3 Descriptive Analysis of the Organisation’s Affective Commitment (OAC) Variable   Note. Mean = 3.917; standard deviation = 0.883; variance = 0.78; median = 4.1; mode = 4. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the hypotheses. The structural model provides all the information related to the test of the hypotheses (Figure 2). This model showed the following fit: Satorra Bentler: χ2SB = 149.830, df = 146; pv = .396; Bentler-Bonett non-normed fit index = .994; comparative fit index = .995; Bollen’s fit index = .995; root mean-square error of approximation = .016. Hypothesis H1 tests the significance of the association between organisation’s affective commitment perceived by HR managers (OAChrm) and organisational citizenship perceived by employees (OCBe). The result of this test (β = .069, t = 0.573) indicates that H1 is not supported (Figure 2). H2 hypothesis proposes the mediating role of the AMOhrm model between OAChrm assessed by HR managers and OCBe. Examining this mediation involves testing the significance of the three paths, OAChrm-OCBe, OAChrm-AMOhrm, and AMOhrm-OCBe, and executing a mediation test. As we have seen in H1, the OAChrm-OCBe path is not significant. Likewise, the result of the AMOhrm-OCBe path is also non-significant (β = -.182, t = -1.049) which means that H2.2 is not supported. However, the association OAChrm-AMOhrm is strongly significant (β = .483, t = 3.38); that is, H2.1 is supported. Additionally, we carry out the mediation test (β = -.04, t = -0.03). Based on this test, we confirmed that the AMOhrm model does not mediate between OAChrm and OCBe; therefore, H2 was not supported (Figure 2). H3 hypothesis established a mediating model where perceived organisational support (POSe) mediates the relationship between OAChrm and OCBe. The analysis of the result indicates that, while the relationships OAChrm-OCBe (β = -.069, t = 0.573) and OAC-POSe (β = -.141, t = -1.272) are not significant, the path POSe-OCBe is strongly significant (β = .527, t = 3.83) which means that H3.2 is supported (Figure 2). The corresponding test to the indirect effect of POSe is not significant (β = -.018, t = -0.103). Thus, we can conclude that POSe does not mediate between OAChrm and OCBe; that is, H3 is not supported. Figure 3 Constrained Model.   Note. 1.645 ≤ t <1.96 (†); 1.96 ≤ t <2.36 (*); t = 2.807 ≤ t < 3.09 (**). To test H4, we tested three direct paths: (1) the OAChrm-AMOhrm model, (2) AMOhrm model-POSe, and (3) POSe-OCBe. Paths (1) and (3) have already been tested in previous hypotheses; however, the AMOhrm-POSe path (H4a) has not been tested yet. The result of this path (2) (β = .333, t = 2.44) reveals that AMOhrm model determines the perception of employees about the organisational support (POSe); that is, H4a is supported. Thus, given that all three direct paths analysed are significant and also the two sequential mediations represented by AMOhrm (β = .161, t = 1.98) and POSe (β = .176, t = 2.27), we conclude that H4 is supported. In summary, the results of the direct effects (Figure 2) show that OAChrm determines the configuration of the HRM system (AMOhrm model), the AMOhrm model influences employees’ perception of organisational support (POSe), and POSe affects organisational behaviour (OCBe). Regarding mediation effects, we found that the AMOhrm model mediated between OAChrm and POSe, and POSe mediated between the AMOhrm model and OCBe. Figure 3 displays a summary of the significant relationships of the model. Finally, “firm size”, as the control variable, seems to have a positive and significant influence on the dependent variable OCBe both in the structural and the constrained model (β = .184, t = 1.939; β = .192, t = 1.944) (Figures 2 and 3). First, we highlight as the main contribution of this article the analysis and measurement of the “organisation’s affective commitment” (García-Cruz & Valle-Cabrera, 2021).To examine this construct, we set out three research questions and one specific objective for each question. We started by asking if companies can be affectively committed to their employees. Next, assuming they can affectively commit to their employees, we wondered what they received in return from their employees. Lastly, we inquired how this exchange occurs; whether it happens automatically or requires intermediate transmission mechanisms. Addressing the first research question and first objective, our research reveals that 83.33% of the HR managers surveyed rated the companies’ level of affective commitment as high or very high (4 or 5 in a Likert scale) (see Table 3). These evaluations show that, according to HR managers perceptions, organisations can become affectively committed to their employees. Reflecting on this result, we propose that considering the affective dimension of the companies’ commitment is crucial to understanding the behaviour of both organisations and their employees. It is a company’s voluntary decision to engage with, make an affective commitment to and consider their needs above what legal regulations require. Furthermore, according to SET, organisations expect equally positive attitudes and behaviours from their employees. This reflection ties into our second objective and answers the second research question raised in the introduction section. However, the results show that the organisation’s affective commitment (OAChrm) does not translate directly into extra-role behaviours (OCBe). It seems that “the given word” by HR managers or the stated intent of the organisation (OAChrm) are an insufficient incentive to motivate employees to perform OCBe. Therefore, we conclude that the HR managers’ plans and commitments regarding employees might not motivate them to perform OCBe. Concerning the third objective and research question, the results associated with the indirect effects of the mediation variables (AMOhrm model and POSe) raised in H2, H3 and H4 hypotheses allow us to reach interesting conclusions. The key conclusion was the positive and significant effect of OAChrm on the AMOhrm model, which allowed us to conclude that when the organisation is affectively committed to their employees, they are more likely to invest in their skills (abilities) and motivation and provide them with the opportunity to properly execute their activities. Therefore, the AMOhrm model is a suitable HRMS for reflecting an organisation’s affective commitment (OAChrm) toward employees. However, the analysis shows that employees do not respond to AMOhrm by performing OCBe, as was expected. It seems that the organisation fails to convey its commitment to employees, either directly or through AMOhrm practices. This is surprising because the literature usually supports the association between the AMO model and OCB (Salas-Vallina et al., 2021). Additionally, the perceived organisational support (POSe) does not mediate the relationship between OAChrm and OCBe as expected. Despite the adversity of the results obtained, we believe they contribute to the literature by questioning associations traditionally accepted as valid. Perhaps these already established relationships require further research. Furthermore, in line with P. M. Podsakoff (2003) and Bou-Llusar et al. (2016), the results confirm the need to consider the differences in perceptions between managers and employees to avoid the common variance problems and get reliable results. Following the structure of our analysis, the next step is to examine the double sequential mediation of the HRM system (AMOhrm model) and the perceived organisational support (POSe) between organisation’s affective commitment (OAChrm) and extra role behaviour (OCBe) raised in hypothesis H4. The key conclusions and practical implications of this paper come from this analysis: OAChrm determines the configuration of the AMOhrm model; the practices associated with the AMO model designed by HR managers make employees feel supported (POSe); this POSe makes them OCBe (see Figures 2 and 3). The analysis showed that POSe mediated the relationship between the AMOhrm and OCBe. Similarly, Rubel et al. (2021) discovered that POS mediates the relationship between high-performance work practices and performance. Accordingly, we conclude that employees perform OCBe only when they actually perceive that the organisation provides them with support (POSe). Therefore, if the practices associated with the AMO model are not perceived, they will not influence employee behaviour. From an organisational practice perspective, our results explain the frustration felt by HR managers when their practices do not yield expected employee behaviours. HR managers must take the employees perceptions into account because the employees’ response to their management depends more on how they perceive the practices applied than on the practices themselves. Another important conclusion for practitioners is that the affective commitment the organisation claims to have concerning employees determines the configuration of the HRM system – in this case, the AMO model. Additionally, the mediating effect of the AMOhrm model between OAChrm and POSe is a novel contribution because, to the best of our knowledge, this result has not been previously reported. This mediation effect means that HR managers try to make employees understand their attitude (OAChrm) through actions associated with the AMOhrm model that make employees feel supported by the organisation (POSe). In other words, the intentions (commitment) of the organisation do not make employees feel supported by themselves. They need concrete actions, such as the practices associated with the AMOhrm model, to feel truly supported. In short, testing the double and sequential mediation of the AMOhrm model and POSe enables practitioners to draw two principal conclusions. First, an organisation’s attitude (OAChrm) determines the actions that the organisation uses to manage employees (AMOhrm model). Second, these actions (AMOhrm) will provoke employees OCBe as they perceive these actions as the organisation’s support (POSe). This confirms that people behave based on how they perceive reality (Ostroff & Bowen, 2016). This study has limitations, which opens new avenues for future research. To start, the study focuses only on the affective dimension of commitment, leaving the doors open to examine the effects of other dimensions, such as continuance and normative. To measure the HRMS, we only considered the HR manager’s perspective. Although, we consider the HR manager to be an expert in the HRM field (Arthur & Boyles, 2007), we also think that the evaluation of an additional manager from a department other than HR would have provided greater consistency to the HRMS measurement (AMO model). While employees’ opinions were collected through three union representatives, having a larger sample of union representatives would have allowed us to verify the opinions of those they represented (employees) in great detail. Therefore, we consider it necessary to clarify that the unions chose these three union representatives as the most suitable to report on employees’ opinions. They were responsible for negotiating the working conditions of collective agreements. Finally, it should also be noted that although an HRM system is usually designed by the person in charge of the HR department, considering the vision of employees (Kehoe & Wright, 2013) would have provided interesting insights to compare managers versus employee perspectives. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: García-Cruz, J. & Valle-Cabrera, R. (2025). From the organisation’s affective commitment to employees’ extra role behaviour: A sequential effect. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 41(2), 65-73. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2025a7 References |

Cite this article as: García-Cruz, J. & Valle-Cabrera, R. (2025). From Organisation‚Äôs Affective Commitment to Employees‚Äô Extra Role Behaviour: A Sequential Effect. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 41(2), 65 - 73. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2025a7

Correspondence: jgarcru@upo.es (J. García-Cruz)Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS