It’s not Just Business: Frequency and Intensity of Basic Emotions at Work and Triggered Events

[Más allá del negocio: la frecuencia, la intensidad y los eventos detonantes de las emociones básicas en el trabajo]

José Navarro1, Rita Rueff-Lopes2, & Malena Otero1

1University of Barcelona, Spain; 2ESADE-University Ramon Llull, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2026a1

Received 3 August 2025, Accepted 8 January 2026

Abstract

Drawing on Affective Events Theory, Event System Theory, and Appraisal Theory, we examine how six discrete emotions arise in daily work. A total of 102 employees provided 1,499 diary entries describing salient events and rating their valence, strength, and emotional impact. Happiness emerged as the most frequent and intense emotion, whereas fear and disgust appeared less often yet could still be powerful. The interaction event valence-event strength predicted every emotion except fear, for which only strength mattered. Gender had minimal effects on intensity but did shape reporting frequency. The analysis also clarifies which event categories typically trigger each emotion—for example, goal attainment for happiness, injustice perceptions for anger, or safety concerns for fear—providing a fine-grained map of affective antecedents. Overall, the findings refine theory by showing that workplace affect extends beyond a simple positive-negative divide. Organizations may shape emotional climates by fostering positive, strong events and mitigating negative, high-impact ones.

Resumen

Basándonos en la Teoría de los Acontecimientos Afectivos, la Teoría de los Sistemas de Eventos y la Teoría de la Valoración, examinamos cómo surgen seis emociones discretas en el trabajo cotidiano. Para ello, 102 empleados proporcionaron 1,499 registros diarios en los que describían experiencias laborales importantes y evaluaban la valencia, la fuerza y el impacto emocional. La alegría apareció como la emoción más frecuente e intensa, mientras que el miedo y el asco surgieron con menor frecuencia, aunque podían ser muy intensos. La interacción entre valencia y fuerza predijo todas las emociones excepto el miedo, para el cual solo la fuerza resultó relevante. El género apenas influyó en la intensidad de las emociones, pero sí en la frecuencia de aparición. El análisis llevado a cabo también aclara qué categorías de eventos desencadenan preferentemente cada emoción—por ejemplo, la consecución de objetivos para la alegría, percibir injusticia en el enfado o preocuparse por la seguridad en el caso del miedo—ofreciendo un mapa detallado de los antecedentes afectivos. Los resultados mejoran la teoría al mostrar que el afecto laboral es más rico que una simple división positivo-negativo. Las organizaciones pueden moldear activamente el clima emocional potenciando experiencias positivas y intensas, al tiempo que atenúan los sucesos negativos con gran repercusión en el día a día.

Palabras clave

Emociones en el lugar de trabajo, TeorĂa de los Acontecimientos Afectivos, Intensidad de la experiencia, Desencadenantes de la experiencia, MĂ©todos longitudinales intensivosKeywords

Workplace emotions, Affective events theory, Event strength, Event triggers, Intensive longitudinal methodsCite this article as: Navarro, J., Rueff-Lopes, R., & Otero, M. (2026). It’s not Just Business: Frequency and Intensity of Basic Emotions at Work and Triggered Events. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 42, Article e260769. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2026a1

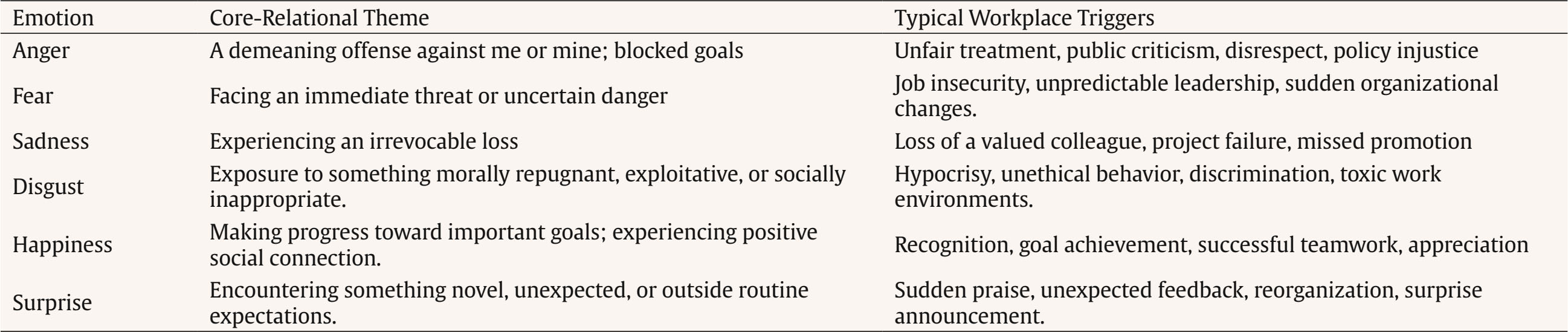

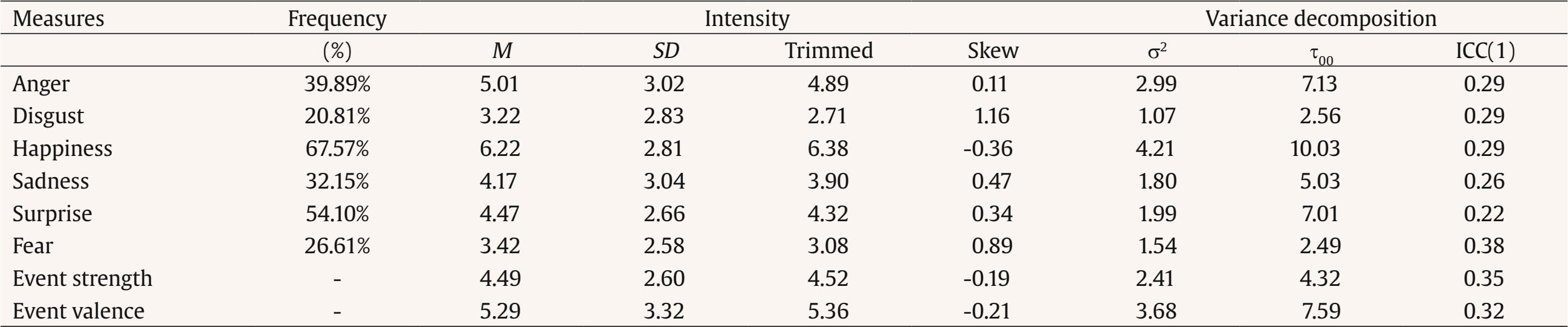

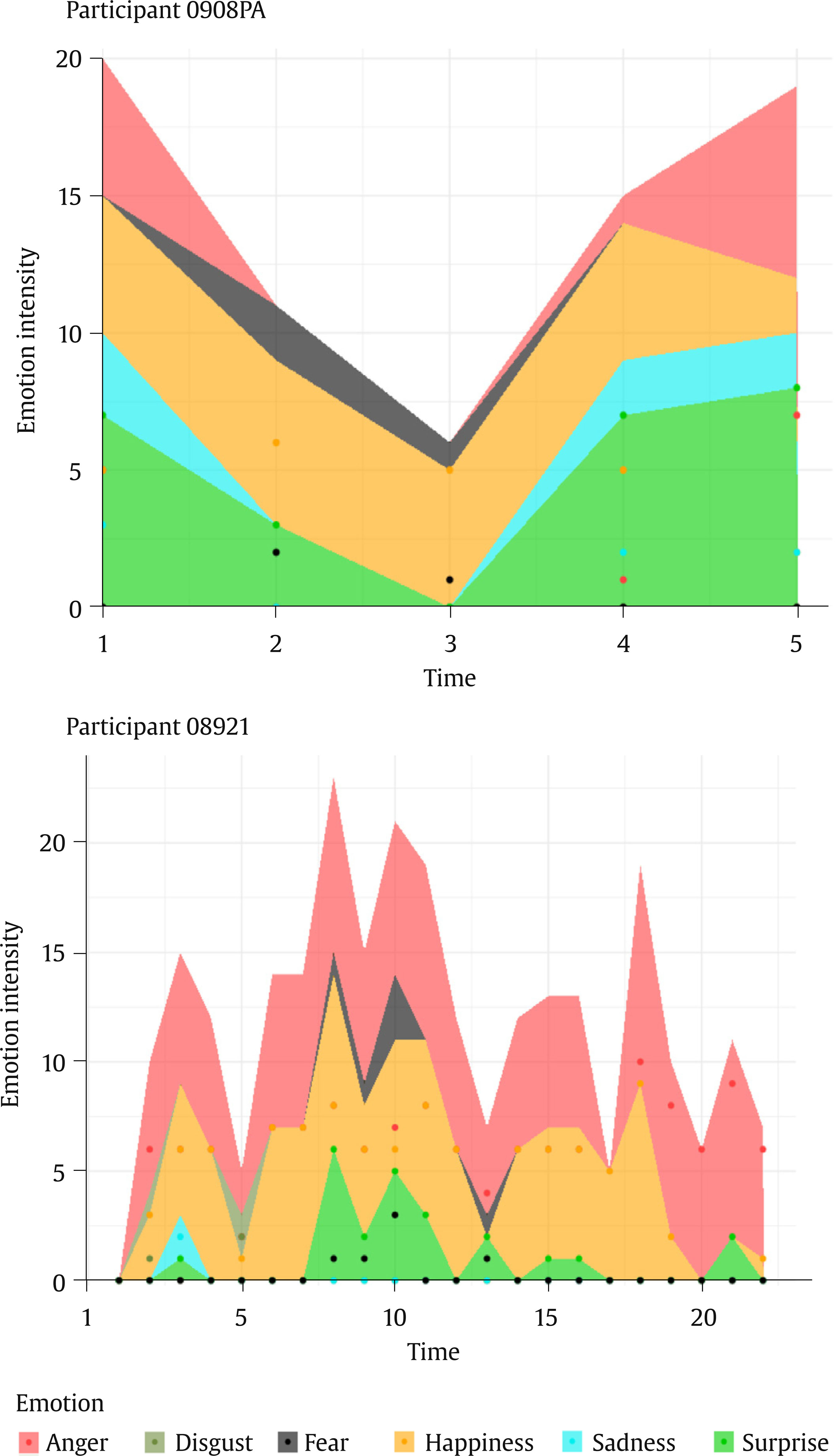

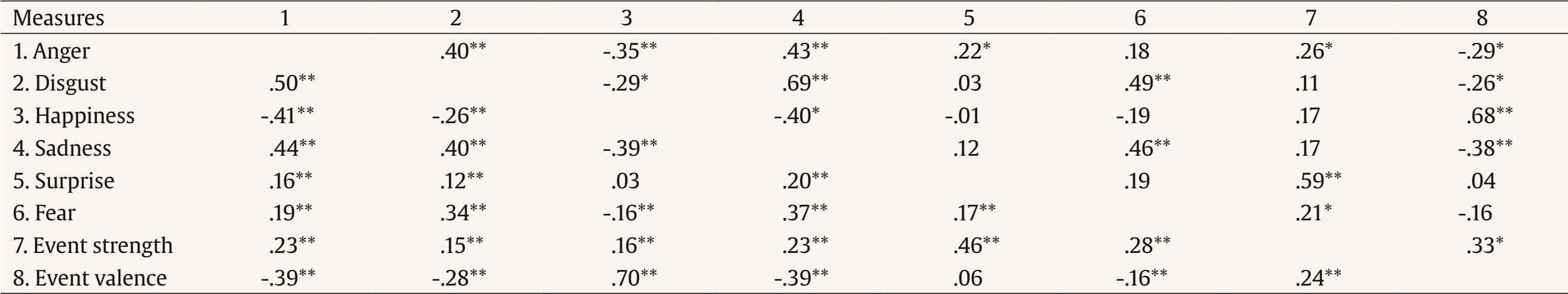

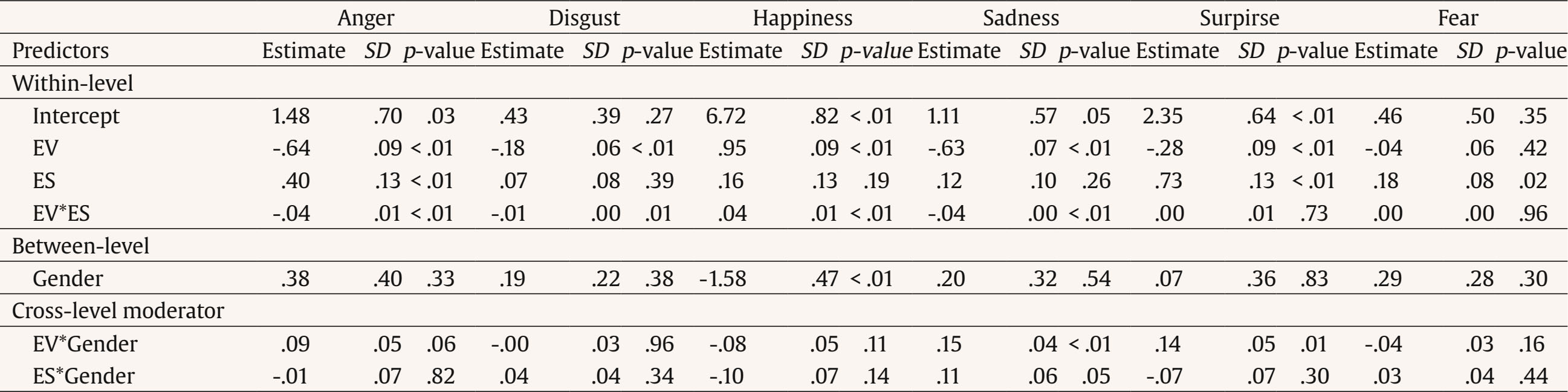

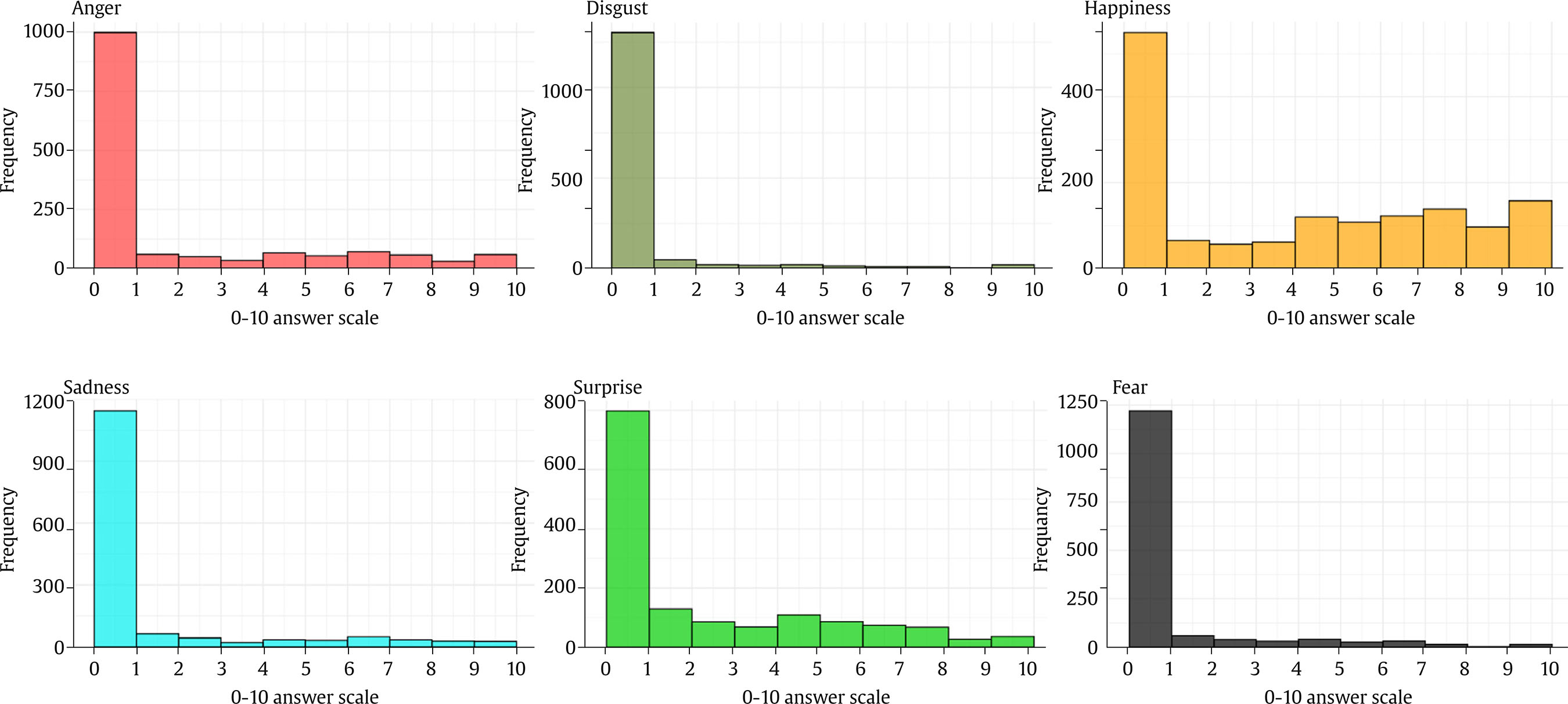

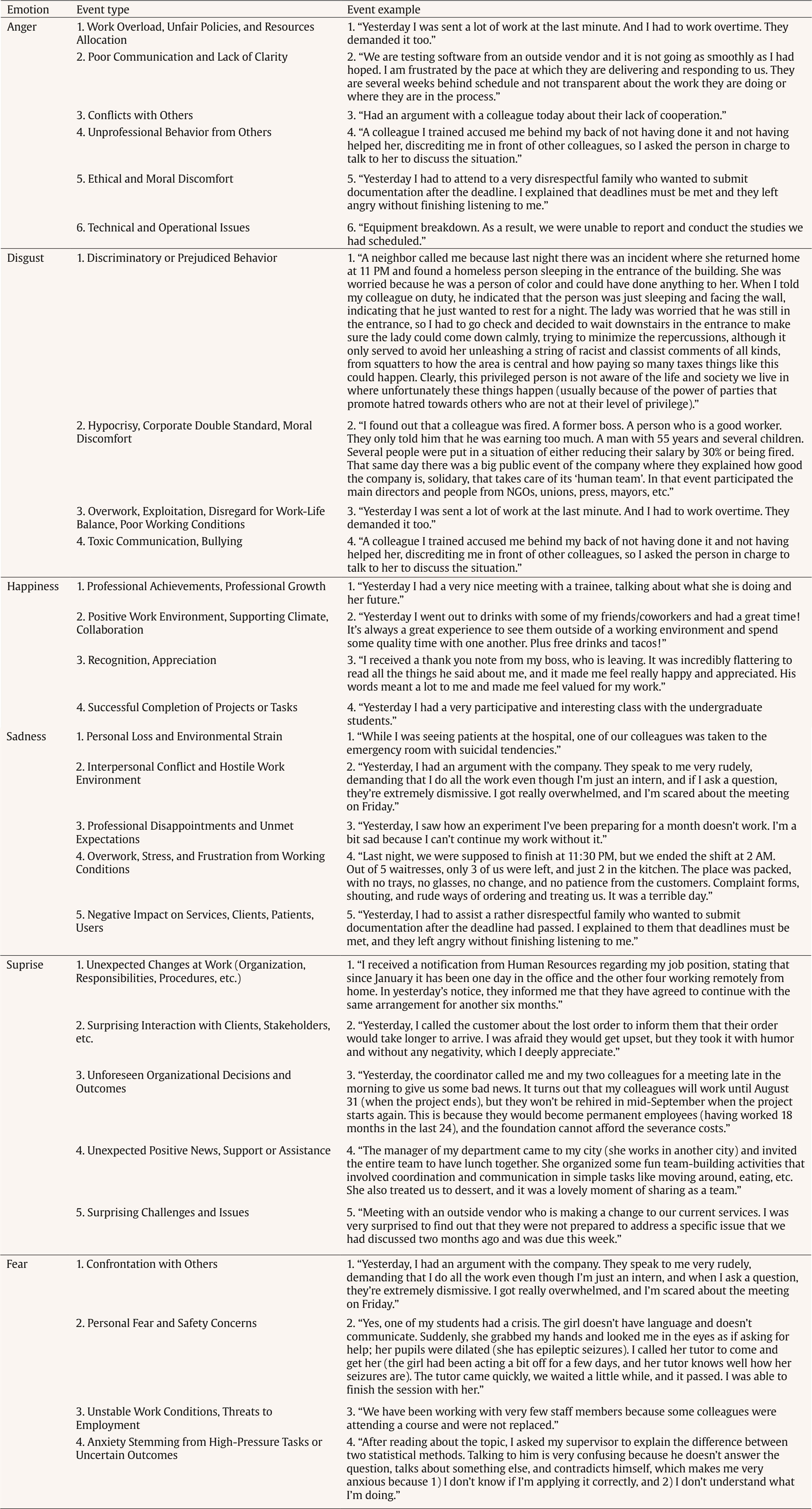

Correspondence: j.navarro@ub.edu (J. Navarro).From its earliest formulations, organizational theory has acknowledged that decisions and behaviors are shaped by human limits and context rather than perfect rationality (March & Simon, 1958). Over time, research has increasingly highlighted that these limits are not only cognitive but also emotional (Barsade et al., 2003). By incorporating affective processes into models of work behavior—and by using intensive, event-based methods—scholars have developed a more complete picture of how employees interpret and respond to the events that punctuate their working lives (Beal et al., 2005; Weiss & Cropanzano 1996). Despite substantial progress, there remains a need for more precise knowledge about which emotions employees experience at work, how intensely they feel them, and what specific events trigger these affective responses. Although affective phenomena are now well established as integral to organizational behavior, research has often examined them in terms of broad affective dimensions (e.g., positive vs. negative affect), which can obscure important distinctions among specific discrete emotions. Emotions such as anger, fear, or sadness, though sharing negative valence, differ markedly in their antecedents, appraisals, and behavioral implications. Understanding these nuances is essential for theory and for designing interventions aimed at improving employees’ emotional well-being. Recent studies have increasingly adopted within-person, longitudinal, or diary designs to capture the dynamic nature of discrete emotions at work (e.g., Barclay & Kiefer, 2019; Rispens & Demerouti, 2016). These approaches have shown that emotional experiences fluctuate substantially across days and events, supporting the idea that emotions should be examined as transient states rather than stable dispositions. However, existing research has rarely considered how specific characteristics of work events—notably their valence (positive or negative meaning) and strength (relevance, novelty, and disruption)—jointly determine the occurrence and intensity of different emotions. Moreover, few studies have systematically identified the types of workplace events that tend to elicit particular basic emotions. The present study addresses these gaps by integrating the Affective Events Theory (events as proximal causes of affect), the Event Systems Theory (features that make events salient, notably event strength), and the Appraisal Theory (evaluations that determine event valence and emotion-specific core-relational themes) to explain when and why discrete emotions arise at work. Using a within-person diary design, we examine the frequency and intensity of six basic emotions in daily work (RQ1), test how event strength and valence (and their interaction) predict these emotions (H1–H5), explore individual differences—with gender specified a priori as an exploratory moderator given mixed prior evidence (RQ2), and identify event categories that commonly trigger each emotion (RQ3). This design would clarify the dynamic, event-based mechanisms through which workplace experiences shape discrete emotional responses. By focusing on discrete emotions, event characteristics, and within-person variability, this research contributes to a more fine-grained understanding of affective experiences at work. It also provides empirical support for recent theoretical developments that integrate the Affective Events Theory with the Event Systems Theory (e.g., Liu et al., 2023), and further extends these frameworks by clarifying whether the interaction between event valence and event strength produces emotional outcomes. Ultimately, this study advances theory and practice by illustrating that workplace affect is richer than a simple positive-negative divide and by revealing how organizations can shape emotional climates through the everyday events employees encounter. Theoretical Background Emotions Emotions are brief affective responses to personally meaningful events that involve experiential, physiological, and behavioral components (American Psychological Association [APA, 2020]; Lazarus, 1991). They differ from moods, which are longer-lasting and not tied to specific causes. In organizational research, emotions are particularly important because work is an inherently social and goal-driven environment where daily events continually elicit affective reactions (Ashkanasy & Dorris, 2017; Fitness, 2000). Although prior studies have often examined affect in broad positive-negative terms (e.g., Watson et al., 1988), growing evidence indicates that such global measures can obscure meaningful distinctions among discrete emotions such as anger, sadness, fear, and happiness (Barclay & Kiefer, 2019; Gibson & Callister, 2010; Weiss & Beal, 2005). In fact, emotions sharing the same valence can have distinct implications for organizational outcomes. For example, a meta-analysis by Shockley et al. (2012) showed that sadness was negatively related to task performance (r = -.28), whereas anger was positively associated with counterproductive behaviors (r = .27). Importantly, these associations were emotion-specific: sadness did not show a significant relationship with counterproductive behaviors, nor did anger with task performance, highlighting that discrete emotions—despite sharing a valence—differ markedly in their consequences. Moreover, emotion theorists such as Lazarus (1991) and Frijda (1986) have also repeatedly documented that emotions differ in their antecedents. Consequently, research has increasingly emphasized discrete emotions as unique responses with distinct antecedents and outcomes. Building on this view, the present study integrates complementary theoretical perspectives that clarify how workplace events generate specific emotional experiences. The Importance of Events as Causes of Emotions at Work The Affective Events Theory (AET) proposed by Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) is one of the main theoretical frameworks for studying how the work environment, through everyday events, shapes employees’ affective responses and how these, in turn, influence attitudes and workplace behaviors. According to AET, relevant work events (e.g., receiving feedback from a superior, having an interpersonal conflict, etc.) provoke emotional reactions that mediate the relationship between said events and attitudinal responses (e.g., job satisfaction) or behavioral responses (e.g., motivation, performance). Following the AET, events would be bounded in time, with positive or negative valence, perceived as relevant to a person’s goals, values, or well-being and able to trigger an emotional reaction (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). At this point, it is important to clarify what would make an event as a salient event. While AET identifies work events as the proximal causes of emotions, it provides limited insight into which events are most likely to elicit affective responses. The Event Systems Theory (EST; Morgeson et al., 2015) defines events as “discrete, discontinuous happenings which diverge from the stable or routine features of the organizational environment” (Morgeson et al., 2015, p. 519). EST proposes that events vary in their strength, which determines their salience and impact on individuals and organizations. Event strength reflects the degree to which an event captures attention, disrupts routines, and demands a response, and it arises from three defining attributes: novelty, disruption, and criticality. Novel events deviate from what individuals typically expect at work, prompting closer attention and cognitive appraisal. Disruptive events interfere with established routines or goals, increasing emotional arousal. Critical events are perceived as important for one’s well-being, status, or performance, making their outcomes more consequential. Together, these dimensions determine the emotional potency of an event—its capacity to evoke stronger or more frequent emotional reactions (Ohly & Schmitt, 2015). How Do Events Generate Emotions? Appraisal, Valence, and Core-Relational Themes Although event strength determines how salient and attention-grabbing a work event is, it does not by itself explain which emotion a person will experience. For that, the Appraisal Theory (Lazarus, 1991; Lazarus, 2006; Lazarus & Cohen-Charash, 2001) provides essential insight. This perspective holds that emotions arise from individuals’ cognitive evaluations—or appraisals—of an event’s relevance and implications for their goals, needs, and well-being. Through these appraisals, people interpret events as beneficial, threatening, unjust, or otherwise meaningful, and these interpretations give rise to distinct emotional experiences. A central concept in this tradition is the core-relational theme, which captures the meaning underlying each discrete emotion (Lazarus, 1999). For instance, anger arises from appraisals of blame or injustice, fear from perceived threat or danger, sadness from loss, and happiness from goal attainment. In organizational contexts, these appraisals occur rapidly as employees interpret daily work events—such as feedback from a supervisor, a conflict with a coworker, or recognition of achievement—through the lens of personal and professional goals (see Table 1). Table 1 Basic Emotions, Core-Relational Themes Based on Lazarus and Example of Typical Workplace Triggers   Within this framework, the event valence reflects the overall evaluative meaning of an event: whether it is appraised as favorable (positive) or unfavorable (negative) for the individual (e.g., Morgeson et al., 2015). The valence thus determines the direction of emotional responses, complementing event strength, which influences their intensity. Positive events (e.g., success, recognition) typically elicit pleasant emotions such as happiness or pride, whereas negative events (e.g., criticism, conflict) evoke unpleasant emotions such as anger, sadness, or fear. The Integrating Affective Events Theory, the Event Systems Theory, and the Appraisal Theory therefore suggest that work events influence employees’ emotional experiences through complementary mechanisms. The event strength makes an event salient and amplifies emotional arousal, whereas the event valence determines whether the experience feels positive or negative. In addition, following Lazarus (2006), the strength of an event—in terms of its novelty, disruption, and criticality—increases the likelihood that it will be appraised as significant for the individual. Thus, strong, personally relevant, and disruptive events have greater potential to elicit intense emotional reactions, such as anger or fear, depending on an individual’s appraisal of the event and its possible consequences. This concept of the event strength will therefore be central to understanding why some work events trigger affective responses while others do not. However, the specific emotion emerges—such as anger versus fear—depends on the core-relational themes that individuals construct through their cognitive appraisals of the event’s meaning (Lazarus, 1999). In this way, the event strength and valence jointly shape the intensity and the hedonic tone of emotions, while appraisal processes define their discrete quality. Individual Differences Also Matter: Gender and Emotions at Work Although work events are the proximal triggers of emotional experiences, individual differences can also influence how employees perceive, appraise, and respond to those events. The AET recognizes that person-level factors—such as personality traits, affective dispositions, and demographic characteristics—can moderate the relationships between work events and affective reactions (e.g., Basch & Fisher, 2000; Miralles & Navarro 2016; Rueff-Lopes et al., 2017; Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). These differences shape both the sensitivity to event cues and the expression of emotions that follow. Among these factors, gender has received consistent attention. Gender socialization and occupational role expectations can influence how emotions are experienced and expressed in organizational settings (Brody & Hall, 2008; Fisher, 2000). Empirical findings, however, remain mixed. Some studies report that women experience emotions more frequently and intensely than men (Linley et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2022), and that they may experience a greater social cost for expressing, for example, anger or frustration. However, other studies have found minimal and non-significant differences in the expression of some of these emotions, such as anger itself (Gibson & Callister, 2010). Moreover, others find minimal or context-dependent differences once job type or hierarchical level are taken into account (Simon & Nath, 2004). For instance, research by Taylor et al. (2022), involving more than 14,000 workers, found that gender-rank interactions or gender-occupational sector are more relevant for understanding the manifestation of emotional responses than gender alone. Gender differences have also been linked to the types of events appraised as emotionally significant and to preferred emotion-regulation strategies (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012; Ptacek et al., 1992). Given these inconsistencies, the present study treats gender as an exploratory moderator of the relationships between event characteristics and discrete emotions. Specifically, we examine whether valence-strength-emotion patterns identified earlier differ between men and women in terms of the frequency and intensity of emotional experiences. This exploratory focus allows us to consider whether gendered norms of emotional experience, expression, and regulation shape affective dynamics in daily work life without assuming a priori directional effects. Research Questions and Hypotheses Formation Taking into account the previous theoretical frameworks, this study establishes various research objectives. First, we aim to clarify the frequency and intensity of different basic discrete emotions (i.e., anger, fear, disgust, sadness, surprise, and happiness) in workplace contexts (RQ1). To our knowledge, this has already been conducted in everyday situations in the study by Zelenski and Larsen (2000), but not in workplace settings. As we have noted, organizational literature has undergone profound changes in recent decades, showing unprecedented interest in the study of affect at work. The choice of the basic discrete emotions listed follows the most established convention to date about what these basic emotions are (e.g., Ekman, 1992). We are aware of the extensive debate in the literature on this topic, but we believe this is not the place to address that discussion. On the other hand, we are interested in studying this frequency and intensity considering emotions as states, so we will apply a within-subject research design through which workers can respond to what emotions and to what degree they have experienced in specific situations. In this way, we hope to overcome one of the usual mismatches in research regarding the inconsistency between the definition of emotions and their measurement. Second, we aim to study the relationship between the events and the emotions experienced. According to AET, positive appraisals signal goal attainment or progress, eliciting pleasant emotions such as happiness. The EST suggests that when such favorable events are also strong—that is, novel, disruptive, or critical—they capture attention and heighten emotional arousal. Therefore, positive high-strength events should generate particularly intense happiness because they combine beneficial meaning with high salience. H1: High-strength events with positive valence will be associated with the emotion of happiness. When work events are appraised as unjust or blameworthy, the Appraisal Theory predicts anger as the corresponding discrete emotion. The AET emphasizes that such evaluations emerge from negative work incidents (e.g., unfair treatment, criticism). When these events are also strong they magnify feelings of injustice and loss of control, intensifying anger. H2: High-strength events with negative valence will be associated with the emotion of anger. The Appraisal Theory links fear to appraisals of threat or potential harm. In the workplace, negative events involving uncertainty, risk, or threat to one’s position evoke fear when perceived as personally consequential. Event strength amplifies this reaction because novel or critical negative events heighten perceptions of danger and unpredictability. H3: High-strength events with negative valence will be associated with the emotion of fear. Disgust arises when individuals appraise an event as offensive, morally repulsive, or violating important norms (Lazarus, 1991). In organizational contexts, experiences such as unethical behavior or disrespect can provoke this emotion. When such negative events are also strong—highly salient and disruptive—they intensify feelings of moral aversion and rejection. H4: High-strength events with negative valence will be associated with the emotion of disgust. Sadness follows appraisals of loss or irrevocable negative outcomes (Lazarus, 1999). Work events involving failure, exclusion, or missed opportunities fit this appraisal pattern. When these events are strong, because they are novel or critical, the sense of loss becomes more salient, leading to stronger sadness responses. H5: High-strength events with negative valence will be associated with the emotion of sadness. In addition to valenced emotions, surprise represents a distinct affective reaction characterized by high arousal and attentional reorientation rather than by a positive or negative valence (Ekman, 1992; Meyer et al., 1997). From an appraisal perspective, surprise emerges when events violate expectations or occur in an unanticipated way, prompting individuals to reassess the situation (Scherer, 2001). Within the EST, such experiences correspond closely to novel and disruptive events—core attributes of the event strength (Morgeson et al., 2015). H6: High-strength events will be associated with the emotion of surprise. Third, we are interested in studying the possible moderator role of gender in the occurrence and intensity of basic emotions at work (RQ2). As previous evidence is inconsistent, as we have noted, we prefer to keep this inquiry as exploratory and not hypothesize any specific expected relationship. Fourth, and finally, since basic emotions are triggered by certain events, we want to clarify what type of events trigger each of these basic emotions in workplace contexts (RQ3). At this point, based on the core-relational themes of emotions, it is expected that there will be differences, nuances, among the triggering events for each of these basic emotions also in workplace contexts. Design and Procedure Considering that emotions are by definition states, we used a within-subject design to assess discrete emotions in work contexts. We applied the day reconstruction method (Kahneman et al., 2004), a method that enjoys a strong reputation in the daily study of affective responses. Participants were asked to complete a daily diary for a period of 10-15 consecutive working days. Participants completed the daily assessments using an online questionnaire. Each morning, they received an email with a personalized link directing them to that day’s survey. In each entry, participants were asked to recall and describe a work-related event that had occurred the day before. Participants were instructed to complete the diary as soon as they received the prompt and to recall and provide a detailed description of the event, including the nature of the event, the individuals involved, and the sequence of actions or interpersonal interactions. The specific instruction for this task was as follows: “Think about an important event that happened at work yesterday. Please describe it in detail, including what happened, who participated, how the sequence of events unfolded, and any other relevant information.” Following the narrative description, participants were asked to assess the emotional impact and perceived significance of the event described. Specifically, they were required to rate how the event made them feel emotionally and assess the valence and strength of the events (for details, see the Variables and Measures section). This approach allowed for the systematic capture of rich, qualitative descriptions of workplace events, complemented by quantitative assessments of their emotional and subjective significance (see Kahneman et al., 2004). Repeated measures over the multi-day period allowed us to track patterns and variations in workers’ experiences and emotional responses over time. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board (University of Barcelona) reference IRB0000309, and were performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants Using personal contacts and social networks, 236 people initially showed interest in participating in data collection. Considering that they needed to be active workers and commit to answering the diary for 10-15 days, we ultimately obtained a sample of 102 workers with at least 5 daily entries, who reported a total of 1,499 registers. This results in an average of about 14.6 registers per participant. The number of 5 registers has been argued by several authors as necessary for parameter estimation in multilevel analysis with longitudinal data (e.g., Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013). The final sample consisted of 58% women, with an average age of 39.5 years (SD = 13.8) and working approximately 32.7 hours a week (SD = 13.6). The professional sectors of these participants were very diverse: 18% were technicians and associate professionals, 14% were scientific and intellectual professionals, 8% were managers, 6% were service workers and shop and market sales workers, etc. In this final sample of 102 participants, there were no differences in gender, professional sector, or hours worked compared to the initial sample of 236 participants. However, there was a difference in age: the final sample was older on average (39.9 years) than the initial sample (37.7 years). In addition, because we had information on several dispositional variables for these participants (i.e., positive and negative affectivity measured with the PANAS, Watson et al., 1988; Big Five personality traits measured with the NEO-PI, Costa & McCrae, 1985, and with the BFI, Gallardo-Pujol et al., 2022 and optimistic and pessimistic attributional styles measured with the ASWQ, Navarro et al., 2025), we conducted the same comparison and found no significant differences in any of these dispositions. Variables and Measures The measures used in this study were selected for their strong conceptual alignment with the theoretical frameworks applied—Affective Events Theory, Event Systems Theory, and Appraisal Theory. Basic Discrete Emotions Discrete emotions (anger, disgust, happiness, sadness, surprise, and fear) were assessed with single items on 0 = none to 10 = a lot scales, following prior diary and within-person studies that prioritize brevity and sensitivity to momentary affective states (e.g., Barclay & Kiefer, 2019; Linley et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2022). This approach ensures minimal participant fatigue across repeated measures while preserving construct validity for basic emotions (Zelenski & Larsen, 2000). As subsequent analyses will consider both the frequency and intensity of these emotions, the frequency was defined as the percentage of times (i.e., registers) when the worker marked the emotion with a value greater than 0. Intensity was defined as the value, between 1 and 10, marked by the worker. A similar procedure was previously used by Zelenski and Larsen (2000). Event’s Strength Following the theoretical proposal of Morgeson et al. (2015) in the EST, the strength of the events was measured using three items related to their relevance (“How relevant do you consider this event?”, from 0 = not at all to 10 = very relevant), novelty (“How novel was this event for you?”, from 0 = not novel to 10 = very novel), and disruption (“Was the event disruptive (did it interrupt or change previous activity?”, from 0 = little to 10 = a lot). The measure of event strength showed reliable scores using multilevel statistics (RkF = .96). This measure was chosen over other alternatives (e.g., single global strength ratings) because it captures the multidimensional nature of event strength and aligns with the theoretical proposition that these attributes jointly determine an event’s attention-grabbing power. Event’s Valence Finally, event valence was measured with a global item assessing the perceived positivity or negativity of the event (“How do you generally rate this event?”, from 0 = very negative to 10 = very positive), consistent with prior event-based affective research (e.g., Ohly & Schmitt, 2015). This measure offers a parsimonious yet robust indicator of overall evaluative meaning, corresponding to the appraisal of event favorability proposed by Appraisal Theory and EST. Together, these measures provide theoretically grounded and empirically supported operationalizations suited to capture dynamic emotional processes in daily work life. Data Analysis Descriptive analyses were performed for all measures. We also calculated multilevel correlations, at both within and between levels, among all measures. To study the potential effect of events on emotions, as well as the possible moderating role of gender in this relationship, we used multilevel models (i.e., growth modeling) following the steps proposed by Bliese and Ployhart (2002). As it is usual in these analyses, within-participant predictors (i.e., event valence and strength) were centered using group-mean centering. All these quantitative analyses were conducted in R (mainly using the psych, multilevel, and lme4 packages). Finally, to study the possible trigger events for each emotion, a content analysis was performed on the events that elicited emotional responses. Given the large number of events (1,499 registers), to simplify the analysis, events associated with extreme evaluations for each of the discrete emotions (the top 25% of values) were selected considering the range scale. This specifically means considering values greater than 7 in each of the emotions as specific events to analyze. A content analysis of these events was conducted by two observers who proposed category systems until an agreement of over 90% was reached on 1) the proposed categories and 2) the classification of events within these categories. We report results in the order of our research questions and hypotheses: RQ1 - frequency and intensity of discrete emotions, followed by correlational analysis; H1–H5 tests of event valence and strength (and their interaction) as predictors of emotions, H6 to test of event strength as predictor of surprise, and (RQ2) exploratory gender effects, and (RQ3) qualitative categories of triggering events. Frequency and Intensity of Discrete Emotions RQ1 asked how often and how intensely the six basic emotions occur at work. The frequency and intensity can be seen in Table 2. Happiness was the emotion that was experienced the most frequently (67% of the time), while disgust and fear were the least experienced emotions (20% and 26% of the time, respectively). In terms of intensity and considering the trimmed values, happiness was reported with the highest intensity (6.38 on a 1-10 scale), followed by anger (4.89). At the lower values, disgust clearly appeared as the emotion experienced with the least intensity (2.71). Table 2 Main Descriptive Statistics   Note. Trimmed is the mean after removing 10% of the extreme scores; σ2 represents the within-participant variance; τ00 represents the between-participants variance. In Table 2 it is also interesting to pay attention to the variance decomposition between levels: within-participant (i.e., registers) and between-participants. The different emotions show ICC values around .22-.29 representing a clear indicator that the variability of these emotions is a consequence of situational influences (i.e., the specific trigger events of these emotions that change from occasion to occasion). The emotion of fear warrants additional comment, given its value of 0.38, which indicates that, beyond triggering events, between-level factors —such as participants’ dispositions and job-specific characteristics— must also be taken into account. We also include histograms of the different emotions (Figure 1) to represent their distributions. These representations visually reaffirm the descriptive information presented in Table 2, with happiness showing the highest variability in its distribution within the possible range (0-10), and fear, disgust, and sadness showing the lowest variability in their distributions. Using the communicative power of these graphical representations, in Figure 2 we present two participants, chosen at random, and the representation of their emotional dynamics in the various registers collected for each participant. Both cases, especially the second with a greater number of registers, reflect a complex dynamic in which emotions occur together and change over time. Figure 2 Two Examples of the Emotional Dynamics over Time.   The areas are stacked to facilitate data visualization; the points capture the intensities of each emotion at each temporal register. Correlational Results The correlations between all measures can be seen in Table 3. In these analyses, for simplicity, the full possible response range (0-10) is considered, instead of the intensity range (1-10), for all emotions. This table includes multilevel correlations, that is, correlations at within-level (i.e., registers nested in participants) and at between-level (i.e., registers aggregated at the participant level). At within-level, as expected, negative emotions (anger, disgust, sadness, and fear) show positive and significant correlation values among themselves (around .40, with the highest being .50 for the anger-disgust pair, and the lowest .19 for the anger-fear pair) and, in turn, significant negative values with the positive emotion of happiness (values between .16 and .41). On the other hand, surprise shows positive correlations with all negative emotions and a non-significant value with happiness. Moving to the between level, the previous pattern of relationships is repeated, but with noticeably higher values. For example, the disgust-sadness pair (r = .69, p < .01) at this between-level points to potential dispositional elements (e.g., personality traits) or work-related factors (e.g., types of work, leadership or climate styles at work) as explanations for this frequent joint occurrence of these two emotions. Table 3 Multilevel Correlations of All Measures   Note. Below the diagonal are the within-participant correlations based on n = 1,499 registers nested in 102 participants; Above the diagonal are the between-participants correlations based on N = 102 participants *p < .05, **p < .01. Event Strength and Valence as Predictors of Discrete Emotions We tested H1-H6 with multilevel growth models (within-person predictors group-mean centered). Table 4 reports coefficients. Table 4 Multilevel Modeling Results: Event Valence and Strength as Predictor of Emotions and the Potential Moderator Role of Gender   Note. EV is event valence; ES is event strength; N = 1,499 registers nested in 102 participants. H1 (High-strength events with positive valence will be associated with the emotion happiness) was supported. Event valence strongly predicted happiness (β = .95, p < .01). Event strength also added variance via the valence × strength interaction (β = .04, p < .01), indicating that positive, high-strength events yielded especially intense happiness. H2 (High-strength events with negative valence will be associated with the emotion anger) was supported. Negative valence predicted anger (β = -.64, p < .01). Event strength had a direct positive effect (β = .40, p < .01) and a valence × strength interaction (β = -.04, p < .01), consistent with strong negative events amplifying anger responses. H3 (High-strength events with negative valence will be associated with the emotion fear) was not supported. Event strength predicted fear (β = .18, p = .02), but valence and the interaction were non-significant, indicating that fear was more sensitive to event potency than to evaluative direction in this sample. This aligns with the higher ICC for fear (see Table 2), suggesting a comparatively stronger dispositional/between-person component. H4 (High-strength events with negative valence will be associated with the emotion disgust) was supported. Negative valence predicted disgust (β = -.18, p < .01), and the valence × strength interaction was significant (β = -.01, p = .01), indicating that strong negative events elicited stronger disgust. H5 (High-strength events with negative valence will be associated with the emotion sadness) was supported. Negative valence predicted sadness (β = -.63, p < .01), with a significant valence × strength interaction (β = -.04, p < .01), consistent with high-strength negative events intensifying sadness. H6 (High-strength events will be associated with the emotion surprise) was supported. Event strength was a strong positive predictor of surprise (β = .73, p < .01), indicating that more novel, disruptive, and salient events elicited greater surprise. The effect of event valence was also significant but negative (β = -.28, p < .01), suggesting that unexpected negative events were more surprising than positive ones. This pattern aligns with the appraisal view of surprise as a response to expectation violation and supports the Event Systems Theory proposition that event novelty and disruption—key dimensions of event strength—provoke greater attentional and cognitive reorientation. Taking all together, two key findings deserve to be mentioned regarding the influence of events as predictors of different emotions. First, the valence of events is a clear predictor of different emotions, as evidenced in multiple previous studies based on the appraisal theory. For instance, in the meta-analysis by Yeo and Ong (2024), this relationship was significant in 75% of the hypothesized relations across 309 studies. This is also true in our case, except for the emotion of fear, which will require specific comment later. Secondly, the strength of the event has also been shown to be a significant predictor, both directly, in the case of emotions such as anger and surprise, and through its interaction with the event valence, in the case of all emotions except fear and surprise. That is, event strength provides additional explanatory power in the emergence of these emotions beyond considering only the valence of the event. Exploratory Gender Effects Gender effects were limited. Men reported higher happiness on average (β = -1.58, p < .01; Male = 1, Female = 2), and gender moderated valence effects for sadness (β = .15, p = .01) and surprise (β = .14, p = .01) meaning that women experience more sadness and surprise in response to negative events. All other main and interaction effects with gender were non-significant. These results suggest modest gender-linked differences in reporting intensity for select emotions only. Entering into more detail regarding potential gender differences, considering the frequency of occurrence of each emotion, significant differences were found using Mann-Whitney U test. Specifically, surprise (p < .01) and happiness (p < .01) were more frequently expressed by men, while disgust (p < .05) was more frequently expressed by women. These differences reflect a pattern of interest consistent with proposals of gender-differential socialization discussed in the theoretical development when we consider the frequency of appearance of the emotions. Triggering Event Categories for Each Emotion In Table 5, we present the main categories of events that trigger each of the discrete emotions as identified through the content analysis (RQ3). In addition, we provide an illustrative example with the literal description provided by the participant. More illustrative examples of the proposed categories can be seen in the Supplementary Material. The information reported in this table is very rich, with a considerable level of detail about what types of events are responsible for triggering each of the emotions. It is, in turn, very subjective personal material, as it collects the specific experience that each participant had in the specific situation described. Without intending to repeat the information provided in Table 5, we would highlight how events related to perceptions of organizational injustice, interpersonal conflicts, or unprofessional behaviors generate anger; events related to discriminatory behaviors, hypocrisy, behaviors that reflect potential exploitation or abuse generate disgust; events related to achievements and recognitions, or a good work environment, generate happiness; events related to losses, interpersonal conflicts, or unmet expectations generate sadness; unexpected events, in terms of procedures, outcomes, or social interactions, generate surprise; and events related to conflicts, concerning safety, or threatening situations generate fear. As can also be seen, some categories of events can generate multiple emotional responses. For example, the Conflict with Others category appears in the generation of both anger and sadness. This joint occurrence of emotions in response to the same events was also shown in the correlation table (Table 3), as previously noted. We will now highlight the concurrent appearance of the emotions of anger, disgust, and sadness, which is also reflected in the types of events that generate them. For example, we present two such events that have generated, at the same time, these three emotions (values above 7): Event 1, Participant 0301RG: At the end of the day, a final daily meeting was held to bring up outstanding issues, ask questions, and get face time with key people. I asked a question of the person who is in charge of giving permission for tech requests to go forward. When I explained what I wanted to explore (a change to a feature in our software as requested by a stakeholder), the guy in charge blew up. He turned it into a huge problem, spouting about how these processes shouldn’t be happening between the stakeholders without tech people being involved and consulted. It was mean and bullying and completely unprofessional. There were 6 people on the call. This senior leader has behaved this way before, but I thought he’d moved past it. It was shocking, and another person jumped in and said we should end the call immediately. So I currently have decided not to do anything about it and move forward as if nothing happened. Wish I could do something about it but I know my efforts would be unsuccessful as he has been spoken with in the past. Event 2, Participant 1010DM: Yesterday, I was given extra work in addition to what I already had to do. At first, I was excited because it was something different from the usual, and that made me happy. It was to design a sketch for a graffiti mural for a restaurant. I even made two different designs, one of them I drew from scratch. I was super happy with the result. My boss loved it, but the clients didn’t—they said it was childish and asked for several changes. Additionally, and lastly, we also present two new events that were able to generate antagonistic emotional responses, sadness, and happiness, simultaneously (values above 7). Although less frequent (the correlation between these two emotions was -.39; see Table 3), this combination is also possible: Event 3, Participant 1212CH: A trainee from the Bachelor program has asked me for advice. We are offering an 18-month contract position in my department, and she qualifies for it. Given that she has worked very well over the past few months, she is the ideal candidate. We offered her the position. She requested a personal meeting and told me she’s unsure because she wants to pursue a Master’s in HR. With a heavy heart, I told her that if she has the opportunity, the best choice is to do the Master’s program, ideally full-time and in-person if possible. I know I’m losing out with this advice. However, my strategy as a manager is to prioritize the well-being of the individual—everything else will follow. Event 4, Participant 1212CH: An agent informed me of their resignation (the third one this month). We had this conversation via Skype. The official reason is that they have found another job. However, the real motivation for seeking a new position is that they feel limited here in terms of their skills and opportunities for growth. I expressed, on the one hand, my happiness because I believe that people need to change goals, missions, and activities to maintain their mental health (as long as such a change is feasible). On the other hand, I shared my sadness because they are someone I value and who has been an asset to the team. This discussion revisits our research questions (RQ1-RQ3) and hypotheses (H1-H6) in light of the integrated framework combining the Affective Events Theory, the Event Systems Theory, and the Appraisal Theory. Together, these perspectives illuminate how the strength and valence of work events shape employees’ discrete emotional experiences and, in turn, reveal the affective nature of organizational life. We aim to provide a cohesive interpretation of how workplace events generate happiness, anger, fear, disgust, sadness, and surprise, as well as the broader implications of these emotional dynamics for theory and practice. Workplace Emotions: Frequency, Intensity, and Common Blends Our first research question (RQ1) was to clarify the frequency and intensity of basic emotions (i.e., anger, fear, disgust, sadness, surprise, and happiness) in workplace contexts. In this regard, happiness has been the most frequently experienced basic emotion (in 67% of the recalled events) and the most intensely experienced (average intensity of 6.22). This result is like those found in non-work contexts by Zelenski and Larsen (2000) and, earlier, by Diener and Diener (1996). Just as people generally assess their overall lives positively, workers also tend to report being happy most of the time and, in turn, evaluate their work lives favorably. It seems evident that in workplace contexts there may also be an influence of retention bias in this positive evaluation: it is likely that workers who repeatedly experience negative emotions at their jobs leave those jobs, resulting in a self-selection effect such that workers are often in workplace contexts that they like, that is, that generate positive emotions such as happiness. Alongside happiness, surprise has also been widely reported (on 54% of occasions), particularly in response to strong events, aligning with our hypothesis (H6). These findings support Affective Events Theory’s premise that everyday experiences at work continually generate affective reactions and reinforce Event Systems Theory’s view that event strength amplifies emotional salience. The prominence of happiness and surprise highlights that even in organizational contexts often associated with pressure or conflict, employees primarily interpret daily events through positive or expectancy-violating appraisals. Regarding negative emotions (i.e., anger, fear, disgust, and sadness), these have been experienced less frequently and with less intensity. However, their occurrence in workplace contexts is clearly relevant. Considering these negative emotions, we find it appropriate to distinguish between the emotions of anger and sadness, which have been more frequently (32-39% of occasions) and intensely experienced (values 4.17-5.01), and the emotions of fear and disgust, less frequent (20-26%) and less intense (values 3.22-3.42). Again, the retention processes previously mentioned may be involved in these results (e.g., it is rare to find workers who frequently experience fear or disgust at their jobs and continue in them). The joint occurrence of these basic emotions has also happened in a significant way. As in previous studies regarding basic emotions in daily life (e.g., Vansteelandt et al., 2005; Zelenski & Larsen, 2000), emotions of similar valence (i.e., negative) tend to appear together significantly. This is not surprising since dimensional models of affect (e.g., the circumplex model of Russell, 1980), are precisely based on this idea of clusters of basic emotions that can appear together. In our case, it has been particularly common (r values greater than .40) for the pairs disgust-anger, sadness-anger, and disgust-sadness to appear jointly. Fear, on the other hand, seems to have shown a somewhat different response pattern compared to the rest of the negative emotions. Triggering Events: The Key Role of the Interaction Events Valence and Strength The generation of all basic emotions is clearly related to event valence and strength, as proposed in hypotheses H1–H6. Beyond the well-known effect of valence on emotional responses, event strength interacts with valence, increasing the likelihood of eliciting these emotions. When events are novel, relevant, and disruptive, they have a clear emotional impact on employees through their interaction with the event’s positive or negative valence. Additionally, given the way events were measured (i.e., the event reconstruction method) and that participants were explicitly asked how these events made them feel, we can infer that events play a primary causal role in the emotions experienced. At this point, results confirmed hypothesis H1 (happiness), H2 (anger), H4 (disgust), H5 (sadness), and H6 (surprise). We found only partial support for H3, which posited that high-strength, negatively valenced events would elicit fear. Fear exhibited a distinct pattern compared with the other negative emotions examined. In the descriptive-statistics table (Table 2), it already emerged as the emotion with the lowest within-participant variability (i.e., the highest ICC = .38). Its correlations with the other emotions were also markedly lower than the remaining pairwise comparisons (see Table 3), and in the multilevel model the strength-valence interaction did not predict fear. Only event strength showed eliciting power for this emotion. Accordingly, H3 in its original formulation was only partially supported. Everything suggests that fear is clearly differentiated from the other emotions assessed, and the emergence of potential dispositional components is intriguing. The ICC value indicates substantial between-person variability, which could stem from several sources. These include dispositional factors—such as personality traits like neuroticism (see Marengo et al., 2021, who reported a robust positive correlation in their meta-analysis)—, occupations or sectors that involve genuine risks and thus evoke fear (e.g., the case of service employees; Antoniadou et al., 2018), or unstable working conditions that generate high uncertainty, which has also been associated with fear (e.g., Lebel, 2016). All of these factors may also operate simultaneously. Gender and Emotions at Work Given the lack of consensus in the previous literature, we decided to propose as a research question (RQ2) the study of possible gender differences in the frequency and intensity of basic emotions in workplace contexts and their role as moderator in the relationship events-emotions. As expected, given the previous empirical evidence, we have found mixed results. The results generally lend mixed support to gender-differential socialization theories. Men reported experiencing happiness more frequently, whereas women reported experiencing disgust more frequently. With respect to emotional intensity, gender exerted a significant main effect on happiness (men experienced it more intensely) and moderated the valence-emotion relationship for both sadness and surprise (women experienced stronger sadness and surprise in response to the same negative events). Nevertheless, the findings were not entirely conclusive and were less unequivocal than theory would predict. Organizations represent a context of achievement where social norms about the expression of certain emotions associated with masculinity or femininity can be important. For example, Eagly et al. (1995) observed this in the context of organizational leadership. In our case, one might expect a higher frequency and intensity of negative emotions in women. As we have seen, this has occurred to some extent, but not with the strength proposed by these theoretical approaches. This leads us to reinforce an idea previously founded in other research: it is not gender alone that causes the occurrence of these frequencies and intensities, but rather, gender must be combined with the position held (e.g., leadership position; Taylor et al., 2022) or with the type of work performed (e.g., there are occupational sectors clearly feminized or masculinized) more prone to the generation of certain types of emotions (e.g., in the health and caregiver sector where there are usually more women working, it is more common for negative events such as personal losses, threats to security, or precarious working conditions to occur). Event Content as a Predictor of Discrete Emotions Delving into the details of the events' content, we found that in addition to generating emotions, certain types of events typically trigger each of the basic emotions. Content analysis of these events allowed us a preliminary approach to the types of triggering events for each of the basic emotions (RQ3), finding that, indeed, there are differences in the content of such events. By adopting an inductive approach to category generation grounded in participants’ own narratives, we believe we moved beyond existing theoretical frameworks (e.g., Totterdell & Niven, 2014). Most of the events mentioned by participants have a clear relational nature (e.g., situations with bosses, colleagues, clients), as was proposed by Lazarus (2000, p. 230) when he stated that emotion is “an organized psychophysiological reaction to ongoing relationships with the environment, most often, but not always, interpersonal or social.” Therefore, the psychosocial approach with its focus on social, interpersonal, or more collective interaction, is relevant in this area (e.g., Mesquita, 2022). In the workplace, there is a rich variety of these relational events that can occur. As we have noted, events related to interpersonal conflicts, perceived injustices, or unprofessional behaviors generated anger among participants. This is in line with what was previously found in the review by Gibson and Callister (2010), who identified three areas as the main categories triggering anger: perceptions of fairness and justice, goal interference, and interpersonal conflict. Sadness, on the other hand, appeared in response to events related to losses or unmet expectations. In sports contexts, Martinent and Ferrand (2015) also found that sadness arises in response to a goal congruent condition that changed for the worse, such as an irrevocable loss during competition. Continuing with the negative emotions, but rarer to find, disgust was triggered by events demonstrating situations of discrimination, abuse, or social hypocrisy threats to security were events that especially triggered fear. In another previous review, Antoniadou et al. (2018) proposed that fear appears in response to stimuli that question survival, integrity, or the self-image we have of ourselves. Logically, there are many more details, richer, in the proposed categories of events and in the specific examples collected (see Table 5). Simpler to analyze, we believe, were the triggering events for surprise, which occurred in novel situations, or happiness, which appeared as triggered by events related to recognition, achievement, or positive relationships at work. Again, this result on happiness is in line with what was previously proposed by other authors like Martinent and Ferrand (2015) in sports contexts, suggesting that happiness appears when making mindful progress toward goals. Moreover, and to conclude this point, there have also been events able to generate these basic emotions without apparent incidence of the relational context, as in the case of technical problems or issues with equipment that have been triggers of anger. Theoretical and Applied Contributions These contributions must be interpreted within the refined theoretical framework that integrates the Affective Events Theory, the Event Systems Theory, and the Appraisal Theory, providing a coherent explanation of when and why discrete emotions arise at work. We believe this research broadens the understanding of affect within organizations in several ways. First, responding to the call from various authors (e.g., Brief & Weiss, 2002; Weiss & Beal, 2005), we have focused on discrete emotions rather than just studying affect in general. By heeding this call, this research teaches us several interesting lessons: 1) organizations are a rich context for the manifestation of basic emotions, 2) happiness generally predominates over other emotions, 3) the concurrent appearance of certain emotions is common, as in the case of pairs that include disgust, anger, and sadness, and 4) different events are directly responsible for the emergence of these emotional responses. Secondly, this research helps address a common limitation in previous studies, which often treated basic emotions not as discrete states but as aggregated measures that average across different feelings or moments. Focusing on emotions as transient states, as proposed in the very definitions of emotion, and using intensive longitudinal designs, like the one employed here, allows for a richer and more precise understanding of the emotional experiences workers face in their daily work life, going beyond simple averages about how they generally feel. As Gooty et al. (2009) assert, this type of approach allows for an understanding of emotions in the specific context in which they emerge. For this reason, the knowledge generated from these approaches is also more useful in applied terms by providing detailed information about which types of event cause different emotions. This provides guidelines for human resource managers who are interested in the emotional well-being of their employees. Thirdly, this research represents an empirical contribution that supports two recent theoretical developments, the Affective Events Theory (AET) and the Event System Theory (EST), which are currently receiving significant attention in the literature on affect at work. With respect to AET, this research confirms 1) the affective nature inherent in work and 2) the importance of events as primary triggers of workplace emotions. Regarding EST, this research confirms the significance of event strength, a key concept proposed by this theory. Fourth, this research offers initial insights into these emotional experiences, as well as potential gender differences. As we have repeatedly emphasized, integrated approaches are needed—approaches that move beyond considering gender in isolation and instead acknowledge its frequent interaction with other factors such as hierarchical position or occupational sector. Emerging perspectives on intersectionality within organizational behavior (Weaver et al., 2016) would be valuable in advancing this line of inquiry. Overall, the discussion demonstrates how revisiting the theoretical underpinnings enriched the interpretation of findings. The integration of the Affective Events Theory, the Event Systems Theory, and the Appraisal Theory clarifies that emotions at work are not random or purely dispositional but systematically arise from the interplay between the meaning and intensity of daily events. This theoretical alignment provides a robust platform for future research exploring potential cumulative effects or cross-level emotional dynamics. Limitations Regarding the main limitations of the research conducted, we point out the following four limitations. First, a larger sample of several hundred participants would help to consolidate the findings, although we are aware of the difficulty this entails when using longitudinal data collection. Second, the data collection method itself introduces a potential bias related to participant self-selection, since it is expected that workers clearly dissatisfied with their jobs would not be inclined to answer a daily questionnaire about how they feel at work. Third, although the research conducted begins to highlight the importance of the temporal dynamics of emotions, this study has not considered the quite feasible possibility of cumulative phenomena over time. As proposed by Li et al. (2010), and as we have also observed in this study (e.g., Figure 2), emotions exhibit a temporal dynamic that should be considered in future studies to investigate these possible accumulations of emotional experiences and their potential influence on other aspects of organizational behavior. Fourth, the diary design required participants to select an event that had occurred the previous day, which may have introduced an additional selection bias. Although this procedure minimizes retrospective recall, it may nonetheless lead participants to choose more salient or emotionally intense events—potentially those with more negative valence—thereby limiting the representativeness of the full spectrum of everyday workplace experiences. Future research could address this issue by incorporating random event prompts or by collecting multiple events per day to better capture typical, less emotionally charged episodes. Conclusions This study delves into the complex interplay of emotions within the workplace, highlighting that happiness and surprise are the most frequently and intensely experienced emotions among workers, indicative of a generally positive evaluation of their work environments. Our findings reveal the specific triggers of various basic emotions, such as interpersonal conflicts, achievements, and perceived injustices, which are significantly linked to emotional responses like anger, sadness, disgust, and fear. Additionally, the study illustrates subtle yet insightful gender differences in how emotions are experienced, aligning with theories of gender socialization. These insights not only reaffirm the affective nature of work, as posited by the Affective Events Theory and Event System Theory, but also offer practical implications for designing human resource strategies and workplace policies that consider the emotional well-being of employees, thereby fostering a more supportive and productive work environment. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Acknowledgments We would like to thank Carlos LeSausse, Florencia Villaseñor, and Ruba Ezzeddine for their help in collecting data. Cite this article as: Navarro, J., Rueff-Lopes, R., & Otero, M. (2026). It’s not Just business: Frequency and intensity of basic emotions at work and triggered events. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 42, Article e260769. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2026a1 Funding JN and RRL received financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2020-120148GB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 project number). Supplementary material, dataset and script used for analysis can be found at OSF: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HETSZ References |

Cite this article as: Navarro, J., Rueff-Lopes, R., & Otero, M. (2026). It’s not Just Business: Frequency and Intensity of Basic Emotions at Work and Triggered Events. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 42, Article e260769. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2026a1

Correspondence: j.navarro@ub.edu (J. Navarro).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS