Appreciation and Illegitimate Tasks as Predictors of Affective Well-being: Disentangling Within- and Between-Person Effects

[El reconocimiento profesional y las tareas improcedentes como predictores del bienestar afectivo: la desagregaciĂłn de los efectos intrapersonales e interpersonales]

Isabel B. Pfister1, Nicola Jacobshagen1, Wolfgang Kälin1, Désirée Stocker1, Laurenz L. Meier2, and Norbert K. Semmer1

1University of Bern, Switzerland; 2University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2020a6

Received 15 February 2019, Accepted 12 February 2020

Abstract

This study examines the effects of appreciation and illegitimate tasks on affective well-being. As empirical results often refer to inter-individual effects but are interpreted in terms of intra-individual effects, we try to disentangle the two. In longitudinal multilevel structural equation models with data of 308 participants, appreciation predicted affective well-being in the expected direction both on the within-level and the between-level, whereas illegitimate tasks had a stronger effect on the between level. On the within-level, appreciation buffered the effect of illegitimate tasks for two of the four facets of affective well-being. Demonstrating a convergent and pervasive effect of appreciation on both levels but diverging effects of illegitimate tasks implies that finding on one level may, but need not, work on the other level as well.

Resumen

Este estudio analiza los efectos del reconocimiento profesional y de las tareas improcedentes en el bienestar afectivo. Dado que los resultados empíricos a menudo aluden a los efectos interindividuales pero se interpretan como efectos intraindividuales, intentamos desintrincar ambos. En los modelos de ecuaciones estructurales longitudinales de múltiples niveles con datos de 308 participantes el reconocimiento profesional predecía el bienestar afectivo en la dirección esperada, tanto en cada nivel como entre los distintos niveles, mientras que las tareas improcedentes producían un mayor efecto entre niveles. En cada nivel el reconocimiento amortiguaba el efecto de las tareas improcedentes en dos de los cuatro aspectos del bienestar afectivo. Demostrar un efecto convergente y generalizado del reconocimiento en ambos niveles pero efectos divergentes de las tareas improcedentes implica que el resultado en un nivel puede, aunque no tiene por qué, funcionar también en el otro nivel.

Palabras clave

Reconocimiento profesional, Tareas improcedentes, Intraindividual vs. interindividual, Bienestar, Estrés como amenaza al yoKeywords

Appreciation, Illegitimate tasks, Intra-vs. inter-individual, Well-being, Stress as offense to selfCite this article as: Pfister, I. B., Jacobshagen, N., Kälin, W., Stocker, D., Meier, L. L., & Semmer, N. K. (2020). Appreciation and Illegitimate Tasks as Predictors of Affective Well-being: Disentangling Within- and Between-Person Effects. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 36(1), 63 - 75. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2020a6

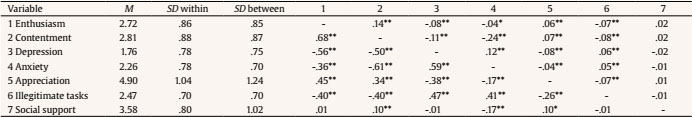

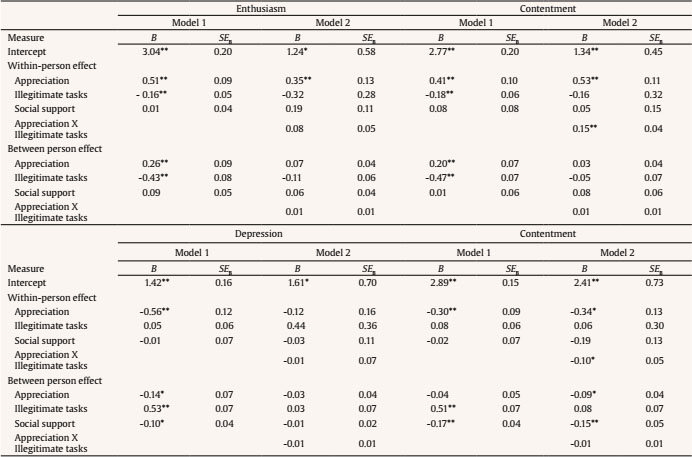

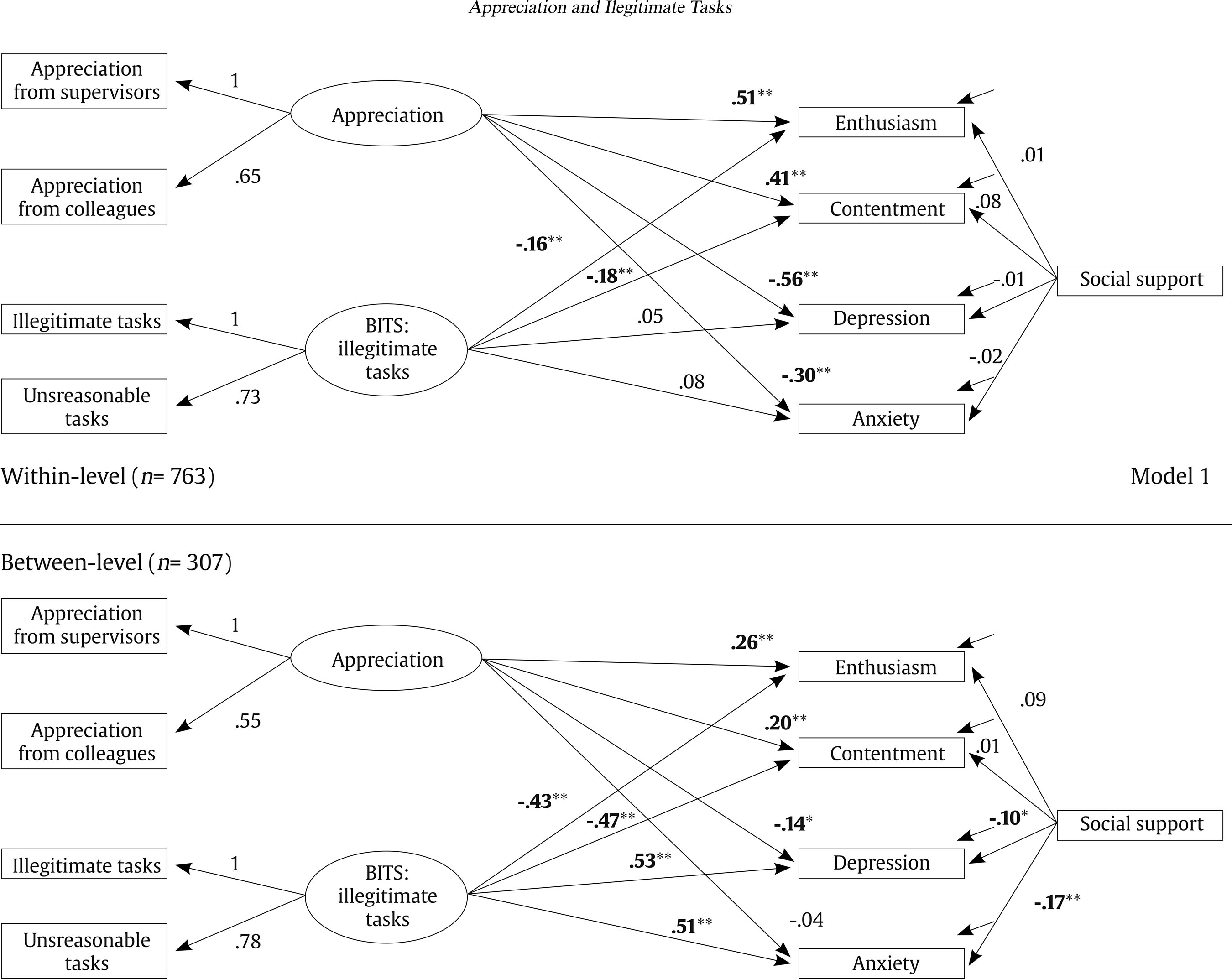

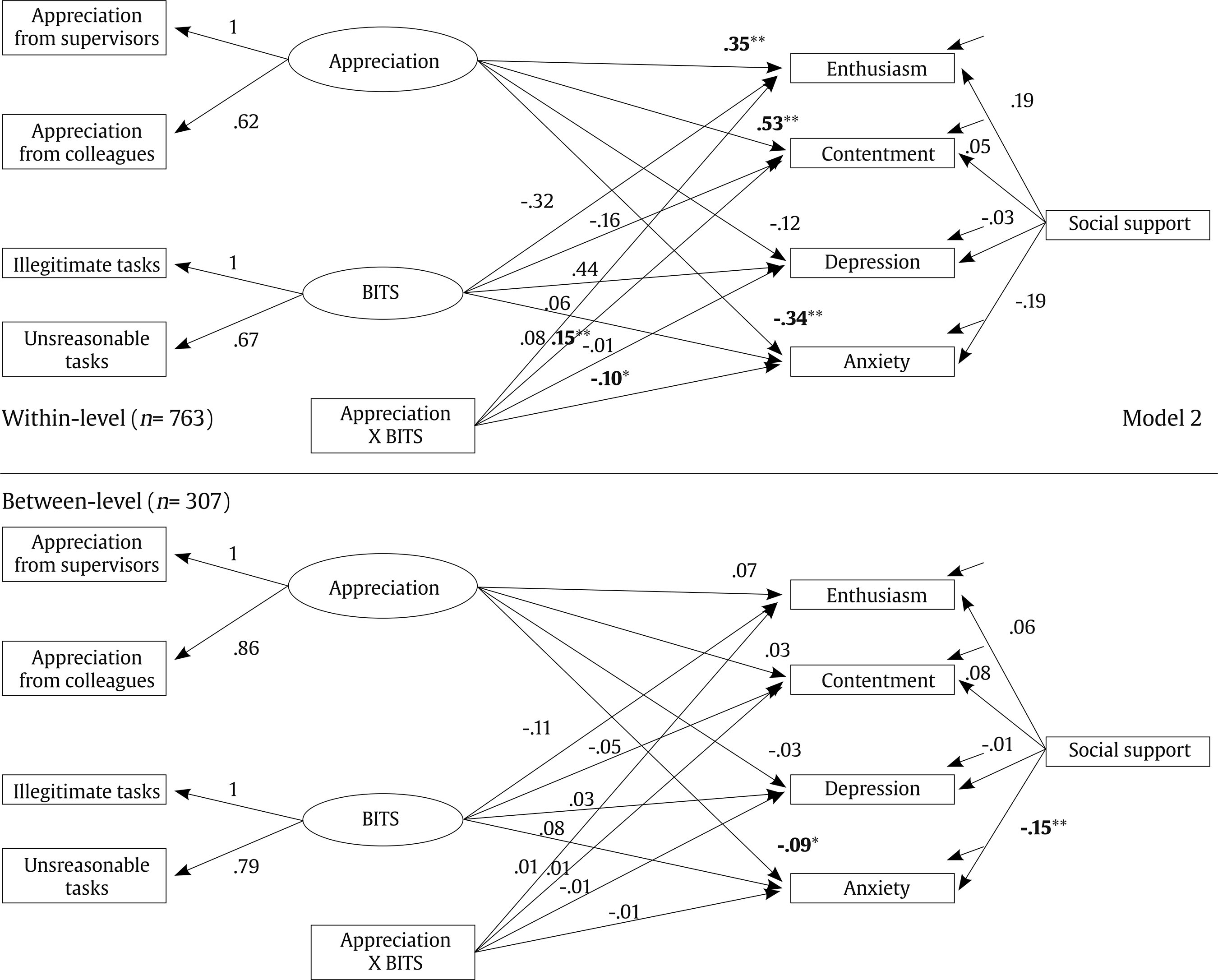

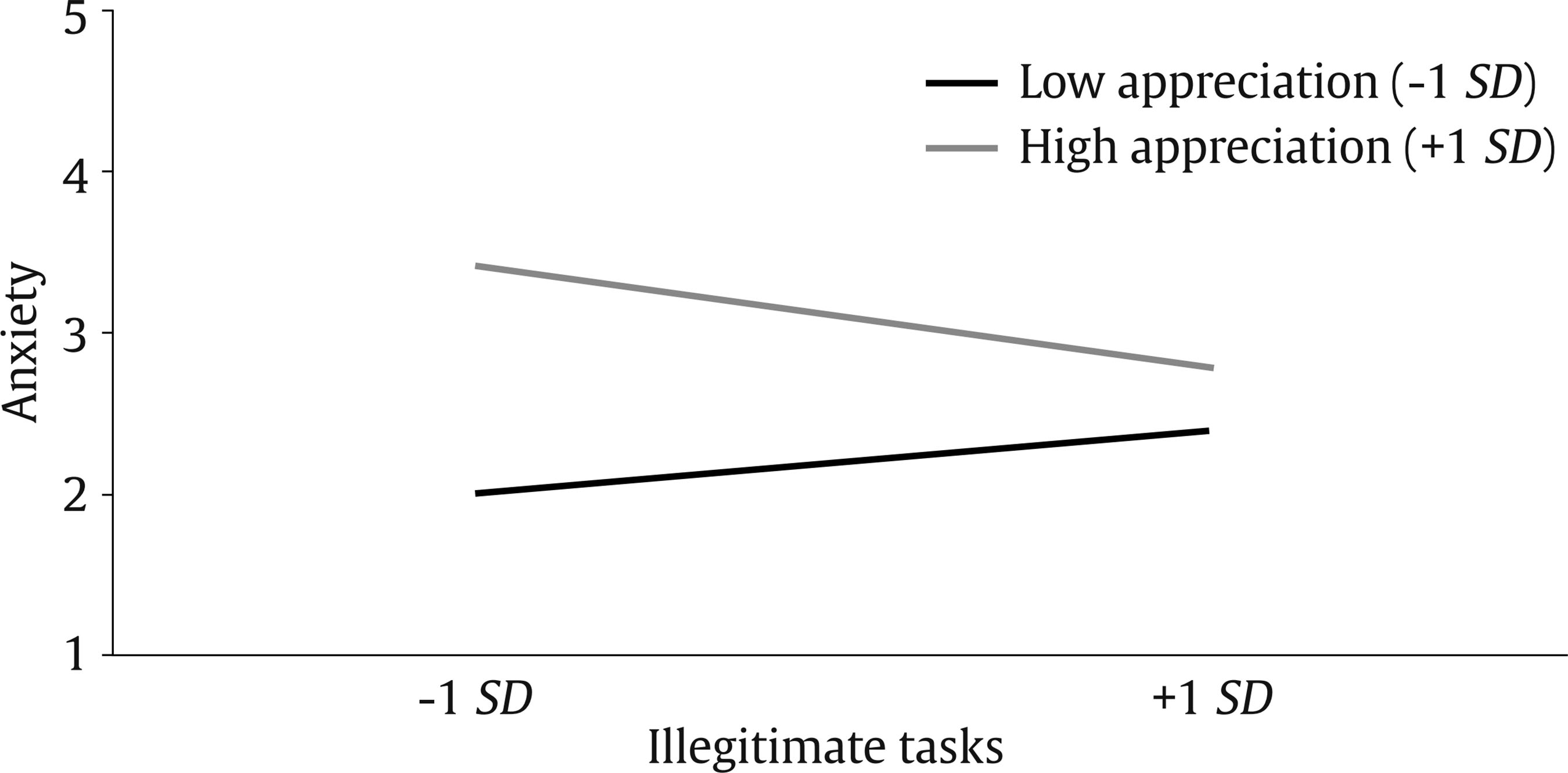

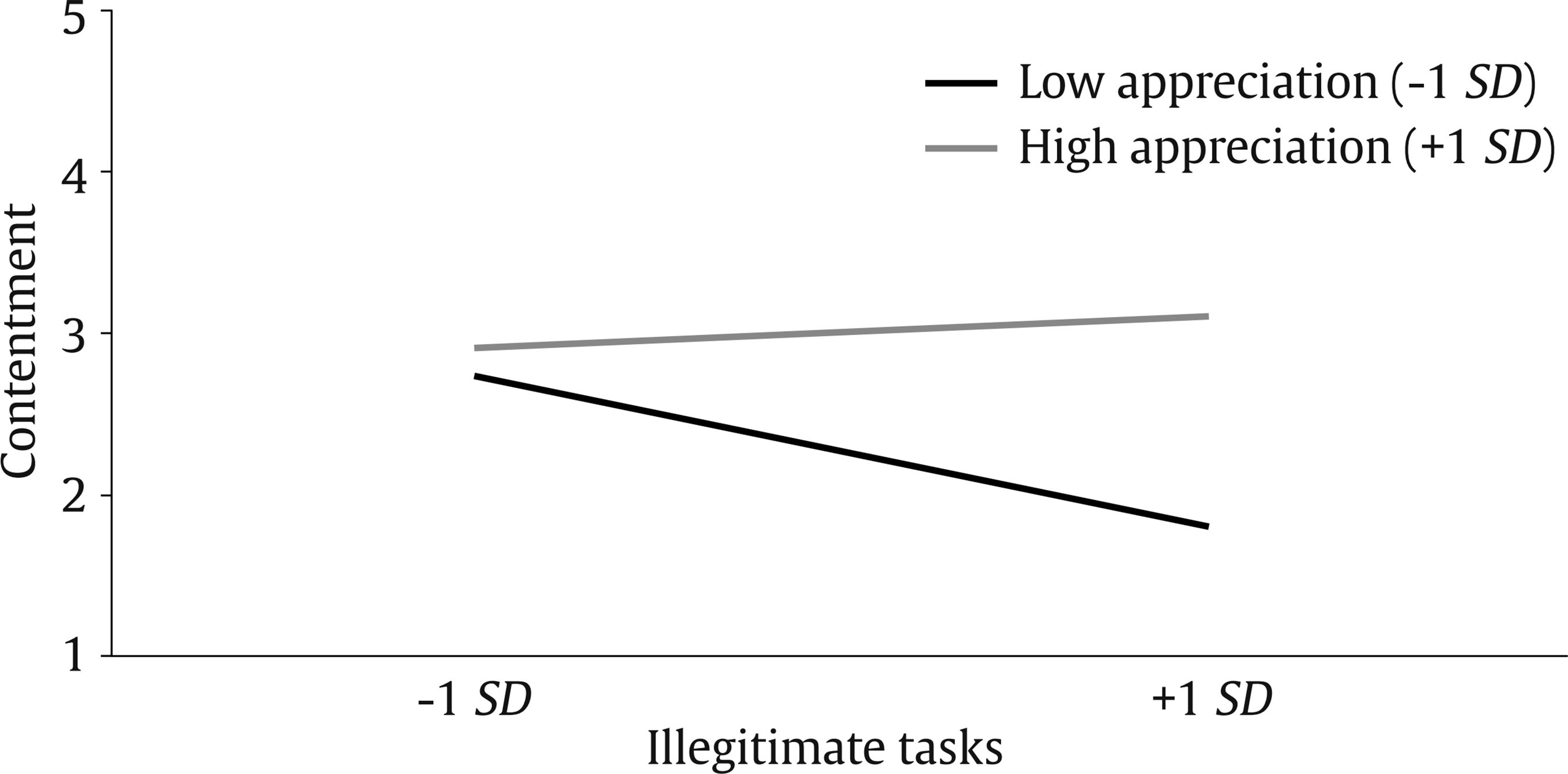

isabel.pfister@psy.unibe.ch Correspondence: isabel.pfister@psy.unibe.ch (I. Pfister).Stress-as-Offense-to-Self (SOS) theory (Semmer et al., 2007; Semmer et al., 2019) is based on the well-established notion that preserving a positive self-view is a basic human concern, and that threats to the self are a source of stress. In the context of SOS theory, the present paper focuses on appreciation as a resource that boosts self-esteem, and on illegitimate tasks as a stressor that represents a threat to the self. SOS theory (Semmer et al., 2007; Semmer et al., 2019) focuses on the need to maintain high self-esteem, in terms of both personal and social self-esteem (Alicke & Sedikides, 2009; Leary, 2012; Miller, 2001). Semmer et al. (2007) and Semmer et al. (2019) argue that appreciation is a key concept regarding boosts to the self. Appreciation implies recognition of one’s qualities and achievements, signals acceptance, and acknowledgment, and thus responds to the need to belong (e.g., Leary, 1999) and boosts self-esteem (Harter, 1993). Social esteem can be threatened by signals of lack of appreciation by others (called “stress as disrespect”, or SAD, in SOS theory). These signals constitute stressors which trigger individual strain. Disrespect can be expressed directly or indirectly (Semmer et al., 2016). Based on SOS theory (Semmer et al., 2007), and based on the importance of a joint analysis of stressors and resources (Job- Demands-Resources model; Bakker & Demerouti, 2007, 2017), in the present paper we focus on a resource that represents a boost to the self (appreciation) and a stressor which threatens the self (illegitimate tasks), analyzing how they influence affective well-being at work. Stressors and resources as predictors of well-being have been investigated in numerous studies (e.g., Danna & Griffin, 1999; Ganster & Rosen, 2013; Sonnentag & Frese, 2013). Most of these studies have focused on inter-individual differences (see Bakker, 2015; Cropanzano & Dasborough, 2015; Ilies et al., 2015). More recently, intra-individual aspects have increasingly been investigated (see Ilies et al., 2015; Ohly et al., 2010), and such studies have increased our understanding of fluctuating aspects of many phenomena, in addition to their stable aspects. Ilies et al. (2015) called for joint consideration of inter-individual and intra-individual aspects. The current study corresponds to this call: we investigated the independent as well as the interactive association of appreciation and illegitimate tasks with affective well-being both on the inter-individual and the intra-individual level. Disaggregation of Between-person and Within-person Influences Many theories in psychology make assumptions about within-person processes, albeit often implicitly. Thus, when a theory postulates that a given stressor is likely to influence well-being, many will assume that people should feel better at times when that stressor is not present, as compared to times when it is (Ilies et al., 2015). However, such theories have been tested mostly with regard to between-person effects (Curran & Bauer, 2011; Ilies et al., 2007). It is increasingly recognized that greater emphasis should be placed on studying within-person processes and investigating how effects on one level relate to effects at other levels, for instance in terms of how personality variables moderate the effects of situational stressors or how the reaction to short-term stressful experiences depends on the accumulation of previous stressful experiences (e.g., Bakker, 2015; Ilies et al., 2015). Frequently effects on different levels are comparable (see Sonnentag & Fritz’s, 2015 summary of between and within person effects of detachment), but there still is a need for more systematic efforts to disentangle the processes occurring at the different levels (Curran & Bauer, 2011; Ilies et al., 2015). This requires studying intra-individual differences in repeated measures (Collins, 2006; Curran & Bauer, 2011; Raudenbush, 2001). Longitudinal data can establish temporal precedence, reduce the number of possible alternative models, and increase statistical power (e.g., Muthén & Curran, 1997). Most importantly in our context, only longitudinal data allow for the disaggregation of between-person effects and within-person (Curran & Bauer, 2011). Although the number of intra-individual analyses has increased over the last decades, inter-individual and intra-individual effects are often not considered simultaneously (Curran & Bauer, 2011). These effects may operate in the same, but also in opposite, directions. Failing to allow for such differences and simply drawing conclusions from one onto the other may result in errors of inference (ecological fallacy; Robinson, 1950; Schwartz, 1994). Following Curran and Bauer (2011), we present hypotheses regarding intra-individual as well as inter-individual effects and try to disentangle these effects using multilevel structural equation modeling in a three-wave study. Within- and Between-person Influences: Possible Mechanisms Intra-individual changes refer to temporal comparisons over time, with one’s own previous values as the point of reference. Inter-individual changes refer to changes in rank-order, that is, in one’s position in a sample. Thus, the two effects are based on different comparisons. The first comparison is temporal in nature and relates current experiences to previous ones; it is intra-individual and is reflected in within-person analyses. The second comparison is social in nature and relates own experiences to others and to social norms; it is inter-individual and is reflected in between-person analyses. It is well established that people appraise the meaning and importance of their experiences in both ways (Strickhouser & Zell, 2015; Zell & Alicke, 2009). We therefore expect main effects for both types of comparisons. For interactions, however, the type of events or circumstances that may act as buffers might be different for inter-individual and intra-individual comparisons, with public visibility as a potentially important aspect. “Social” comparison involves a comparison with others in one’s environment, with others in similar positions elsewhere, with generalized others, or with an internalized social norm (Pettigrew, 2016). Social comparisons therefore are likely to refer to events/circumstances that are “publicly” known. Publicly known stressors may be more difficult to discount than more private ones. “A socially real, publicly known fact cannot be dismissed or ignored as readily as a fact that is known only to the self” (Baumeister, 1996, p. 34). More specifically, it might take resources that are also publicly known to counter such highly visible stressors. By contrast, in temporal comparisons current events or circumstances are being compared to earlier ones, and this comparison may involve many considerations known only to the individual and not be restricted to events that are publicly known. Many more events/circumstances are therefore likely to enter into temporal comparisons, including resources known only to the individual. Such resources may act as buffer even for highly visible stressors, and thus make interactions on the within-person level more likely than interactions on the between-person level. Affective Well-being The well-known concept of subjective well-being (e.g., Diener et al., 2018; Tov, 2018) distinguishes three components: positive affect, negative affect, and satisfaction (Bakker & Oerlemans, 2011). Satisfaction is sometimes referred to as a cognitive component (Tov, 2018) but is better characterized as an evaluative judgment (Diener et al., 2018; Weiss, 2002; Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). The three components are correlated, but not so high as to be indistinguishable. Note that the evaluative versus affective components can also be characterized as “judgements versus experiences” (Diener et al., 2018, p. 253). This is important for our study because it implies that the affective components are more reactive to experiences (“affective events”; Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996), than the evaluative component, which is both more stable and influenced by a wider range of factors, which include the affective components (Suh et al., 1998; Tov, 1998; Updegraff et al., 2004; Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). As we were interested in aspects of work that induce affect by affirming (appreciation) or threatening (illegitimate tasks) the self, we decided to focus on the affective components and to pursue an approach that distinguishes not only positive and negative affect (e.g., Diener et al., 2010) but further differentiates each of these into high- vs. low-arousal components. The affective component of subjective well-being often is conceived in terms of the emotional circumplex (Yik et al., 2011). Each emotion can be seen as a combination of arousal and pleasure. Warr (2007) distinguishes between two axes, one ranging from depression to enthusiasm, the other from anxiety to contentment. On this basis, Warr proposes four quadrants, which represent different combinations of arousal and pleasure: enthusiasm represents high arousal pleasant affect, depression represents low arousal unpleasant affect, anxiety represents high arousal unpleasant affect, and contentment represents low arousal pleasant affect. Although these constructs are correlated, they have been shown to represent distinct constructs (Mäkikangas et al., 2007; Warr et al., 2014). We, therefore, investigate the association of appreciation and illegitimate tasks with these four quadrants. Appreciation as a Resource Appreciation as a Construct in its Own Right The most frequently studied social resource to date is social support; it has been linked to better mental health, more stress resistance, and better physical health outcomes (Cohen et al., 1997; Cohen & Wills, 1985; Viswesvaran et al., 1999). Appreciation, in comparison, has found much less attention. Although recognized as an important resource long ago by William James (James, 1920), and despite findings showing that appreciation may be an especially important resource (van Vegchel et al., 2002), appreciation has seldom been in the focus of research as a construct in its own right; rather it has often been mentioned as part of larger concepts (e.g., the effort-reward imbalance model, Siegrist, 1996; leadership, Yukl, 2013; or social support, Thoits, 1982). Semmer et al. (2007) argued, however, that appreciation is an important concept in its own right. Appreciation implies recognition of one’s qualities and achievements; it signals acceptance and acknowledgment, and thus responds to the need to belong (e.g., Leary, 1999) and boosts self-esteem (Harter, 1993), and it does so in a very direct way (e.g., by praise; Stocker et al., 2014). Other constructs, notably social support, do entail appreciation; more specifically, through its emotional component, which refers to esteem, caring, and respect (Beehr & Glazer, 2001). However, social support goes beyond emotional support, involving tangible help and information as well (instrumental support). Furthermore, social support is typically conceived as support in difficult times (Beehr & Glazer, 2001). In contrast, appreciation is not restricted to difficult times, but may be experienced at any time. Thus, measures of social support do contain appreciation but do not represent a “pure” measure of appreciation. Thus, Semmer et al. (2008) demonstrated that recipients of social support attributed the beneficial effects of “instrumental” support episodes largely to its emotional “component” (exclusively for 49% of the episodes, and partly in another 15%). If appreciation is such a central component of social support, it seems worthwhile to investigate appreciation directly, rather than only as part of the broader construct of social support. However, to test our claim that appreciation should be assessed directly, we control for social support in our analyses. Existing studies have confirmed the effects of appreciation. Thus, a cross-sectional study by Stocker et al. (2010) showed an association of appreciation with well-being indicators, such as job satisfaction and reduced negative emotions, over and above social support and interactional justice. Bakker et al. (2007) found that the positive effect of appreciation on work engagement was the strongest of six resources tested. Semmer et al. (2006) reported cumulative effects of appreciation in that the number of times participants reported high appreciation at work predicted job satisfaction at the last wave in a study with four waves of measurement. A recent event sampling study found that appreciative events throughout the workday predicted well-being in terms of serenity after work intra-individually (Stocker et al., 2014). Intra- and Inter-individual Effects of Appreciation Intra-individual effects refer to temporal comparisons, evaluating whether one has recently received more, equal, or less appreciation compared to earlier times. As appreciation implies a boost to the self, a positive effect on well-being should occur at the within-person level to the extent that this evaluation yields a positive result. Inter-individual effects refer to social comparisons, involving others in comparable situations or an assumed general standard. A positive comparison in this social comparison should also boost the self, resulting in a positive effect on well-being at the between-person level. Thus, both effects are theoretically plausible. As within-person effects and between-person effects often occur simultaneously, (Strickhouser & Zell, 2015; Zell & Alicke, 2009), we expect appreciation to be related with well-being on both levels. We postulate that appreciation is positively related to well-being, both on an intra-individual as well as on an inter-individual level. Specifically, we hypothesize: Hypothesis 1: Both on the within-person and the between-person level, appreciation is positively related to enthusiasm (H1a) and contentment (H1b), and negatively related to depression (H1c) and anxiety (H1d). Illegitimate Tasks as a Stressor The Concept of Illegitimate Tasks and Pertinent Research Illegitimate tasks represent a type of task-related stressor, derived theoretically from role and justice theories within the framework of “Stress-as-Offense-to-Self” (SOS; Semmer et al., 2007; Semmer et al., 2015). This theory is based on the widely accepted notion that preserving a positive self-view is a basic human goal (Alicke & Sedikides, 2009). Occupational roles typically contribute to people’s self-view (Ashforth, 2001; Eatough et al., 2016). Roles entail expectations about what the role-incumbent can be expected to do or to be responsible for (Katz & Kahn, 1978). Illegitimate tasks focus on the other side, referring to tasks that cannot appropriately be expected from a given person, as they are not considered as part of one’s work role (Semmer et al., 2007). There are two facets of illegitimate tasks, unnecessary and unreasonable (Semmer et al., 2015). Employees may think a task should not exist at all (e.g., having to write reports one expects to be disregarded during decision making); such tasks are called unnecessary tasks. Other tasks are perceived as somebody else’s duty (e.g., a hospital physician having to organize beds for patients); such tasks are called unreasonable tasks. As roles not only reflect expectations, but also tend to become part of one’s identity (Ashforth, 2001; Chreim et al., 2007; Haslam & Ellemers, 2005; Meyer et al., 2006; Warr, 2007), violating role expectations is likely to offend one’s professional identity. From that perspective, illegitimate tasks constitute “identity-relevant stressors” (Thoits, 1991), and thus a threat to the self. Furthermore, the assignment of illegitimate tasks fulfills the conditions for unfairness specified by Folger and Cropanzano (2001) in terms of three conditions, called would, could, and should (see also Weiner, 2014). As illegitimate tasks are perceived as inappropriate, the focal person “would” be better off if he or she would not be assigned such tasks. Furthermore, the person assigning the task “could” and “should” have acted differently. Thus, illegitimate tasks are likely to be perceived as unfair. Lack of perceived fairness implies that one’s interests and concerns are not respected as one would deserve (Miller, 2001). Such information is used to infer one’s acceptance as a group member; thus, it signals one’s social standing, which affects one’s social esteem (De Cremer & Tyler, 2005). Illegitimate tasks are not illegitimate per se; it rather depends on the context if they are perceived as such or not. A task may be considered legitimate in the context of a given role but not of another (e.g., organizing beds may be a legitimate task for administrative personnel). Being assigned tasks one considers illegitimate signals a lack of respect for one’s professional role (Semmer et al., 2015). Research on illegitimate tasks is just emerging but encouraging. The first article on illegitimate tasks (Semmer et al., 2010) focused on counterproductive work behaviour (CWB), which constitutes a behavioral strain that damages both organizational members and organizations as a whole. CWB has been shown to be related to many stressors (Spector & Fox, 2005) but offers itself specifically for investigating justice-related variables, as counterproductive work behavior often is regarded as a way of “getting even” and restoring justice (Tripp & Bies, 2009). Semmer et al. (2010) argued that illegitimate tasks may be regarded as a specific instance of lack of justice. However, the concept is not adequately covered by typical measures of justice, and Semmer et al. (2010) could show that illegitimate tasks can be distinguished from direct measures of justice (an aggregate of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice) and from justice-related concepts (i.e., effort-reward imbalance; Siegrist, 1996). In two studies, illegitimate tasks were related to CWB, over and above effort-reward imbalance (Study 1) and organizational justice (Study 2; Semmer et al., 2010). Subsequent studies have investigated a broad range of strain indicators (Semmer et al., 2019). To present a few examples, Björk et al. (2013) reported associations with stress and satisfaction among Swedish managers, and van Schie et al. (2014) with reduced intent to remain and self-determined motivation among volunteers. Madsen et al. (2014) found a negative effect of unnecessary tasks on mental health over time. Semmer et al. (2015) found negative associations of illegitimate tasks with various indicators of well-being, such as burnout, self-esteem, and irritability beyond a number of other stressors as well as organizational justice in two samples, and an effect on feelings of resentment towards one’s organization and irritability over time in a third sample. Schmitt et al. (2015) report motivating effects of time pressure only when unreasonable tasks were low. Illegitimate tasks have been found to be related to turnover intentions (Apostel et al., 2017), to job satisfaction and intrinsic motivation (Omansky et al., 2016), and to student satisfaction, anxiety, and emotional exhaustion (Fila & Eatough, 2017). Intra-individually, Kottwitz et al. (2013) demonstrated an effect of illegitimate tasks on cortisol-levels, Eatough et al. (2016) on state self-esteem, Pereira et al. (2014) on sleep quality, and Sonnentag and Lischetzke (2017) on negative affect and state self-esteem at the end of a workday, and on psychological detachment from work. It therefore is fair to say that the theoretically postulated negative effects of illegitimate tasks on well-being have now been confirmed in a number of studies. Altogether, illegitimate tasks have been shown to relate to strain in many studies by now (Semmer et al., 2019; Fila et al., in press). Intra- and Inter-individual Effects of Illegitimate Tasks As with appreciation, it seems theoretically plausible that people use both temporal (i.e., intra-individual) and social (i.e., inter-individual) comparisons while interpreting illegitimate tasks (Strickhouser & Zell, 2015; Zell & Alicke, 2009), and we therefore expect effects of illegitimate tasks on both levels as well indeed, both intra-individual and inter-individual effects have been shown, although the majority of studies focused on inter-individual effects. We therefore postulate: Hypothesis 2: Both on the within-person and the between-person level, illegitimate tasks are negatively related to enthusiasm (H2a) and contentment (H2b), and positively related to depression (H2c) and anxiety (H2d). The Buffering Effect of Appreciation The job demands-resources model postulates that resources may attenuate the negative impact of job demands (i.e., stressors) on strain and well-being (buffering effect; Bakker et al., 2007), implying that the relationship between stressors and well-being is weak(er) for those enjoying a high degree of job resources (Bakker et al., 2007). Many findings have confirmed such a buffering effect (Bakker et al., 2007; Jex & Bliese, 1999; Kottwitz et al., 2013). Regarding appreciation and illegitimate tasks, it is theoretically important that both contain a social message. Appreciation signals that one is valued and acknowledged; by contrast, illegitimate tasks signal a lack of respect for one’s professional identity. The message sent by appreciation is rather direct, as appreciation is, for the most part, expressed directly in social interactions (Stocker et al., 2014). By contrast, the message sent by assigning illegitimate tasks is more indirect. It seems theoretically plausible that the impact of illegitimate tasks might be reduced if a supervisor directly signals appreciation. Thus, the processes postulated by JD-R theory for resources and stressors in general are likely to apply to the two specific variables we investigated. This reasoning is supported by a recent study that found an interaction between illegitimate tasks and appreciation in predicting turnover intentions on an inter-individual level (Apostel et al., 2017). As we expect the processes involved to operate in the same direction intra-individually and inter-individually, we expect the buffering effect to occur both on the between-person and the within-person level. We therefore postulate: Hypothesis 3: Both on the within-person and the between-person level, appreciation buffers the effect of illegitimate tasks on enthusiasm (H3a), contentment (H3b), depression (H3c), and anxiety (H3d), such that negative effects of illegitimate tasks are weaker when appreciation is high. Buffering Effects: Possible Differences between Levels We argued above that rather public events/circumstances are not easily buffered on the inter-personal level because the events/circumstances to be considered are more limited. By contrast, in temporal comparisons, which are more “private” in nature, many more aspects may be taken into account. These theoretical considerations have implications for the buffering effect of illegitimate tasks both levels. We did not assess to what extent appreciation and illegitimate tasks reflected “private” or “public” events and circumstances in the sense discussed above. It seems plausible, however, that appreciation is more private and less public than illegitimate tasks. The reason is that appreciation can be shown in just about any situation – from (private) interactions with the supervisor to being praised in a meeting (public). It seems likely, therefore, that appreciation is composed of both private and public elements. Illegitimate tasks, on the contrary, involve carrying out activities that are likely to be noticed by colleagues (although they may be “assigned” “privately”), implying that they are likely to be largely pubic. Thus, appreciation entails a mixture of public and private elements, whereas illegitimate tasks entails mainly public elements. Based on these considerations, we expect that appreciation is more likely to buffer the effects of illegitimate tasks in within-person than in between-person analyses. However, as our thinking about these issues was still somewhat vague when we started our study, and became more specific only later, we refrain from postulating a hypothesis about this effect but rather ask a research question. Research Question: Are buffering effects of appreciation more frequent on the within-person as compared to the between-person level? Participants and Procedure We contacted the HR representatives of 20 organizations in Switzerland and sent them material about the study. Six of these organizations agreed to inform their employees about the study by passing on our material. These organizations comprised a hospital, a library, a telecommunication company, a production firm, and two government institutions. HR then sent us a list with e-mails of employees agreeing to participate. Data were collected over three waves with a time lag of two months between each wave. Employees could fill in questionnaires during working hours. Unfortunately, our procedure of concocting the sample does not allow us to calculate a participation rate, as most organizations did not contact employees directly but rather via supervisors, not all of whom passed the information on to their employees. We therefore do not know the number of employees who received our information. Altogether, 308 Swiss employees participated in the study from June 2013 to January 2014. A wide variety of jobs was represented in the sample: nurses, doctors, engineers, economists, administrators, quality specialists, assistants, financial specialists, prison guards, politicians, logistic experts, HR specialists, account managers, and IT specialists. The sample consisted of 161 (52.3%) female and 147 (47.7%) male participants. Mean age was 43.9 years (SD = 10.4, range 20 - 65). Participants had been working in the same company for an average of 10.7 years (SD = 8.8). On average, they were employed at 88% (SD = 17.7) of a full time equivalent. Of the original 308 participants, 253, or 82.1%, also participated at wave 2 and 216, or 70.1%, at wave 3. At each wave, participants filled out the same questionnaire assessing conditions at work, including resources and stressors as well as affective well-being states. Drop-out analyses revealed only one difference between drop-outs (at any time) and those participating in all three waves, indicating that enthusiasm was somewhat lower for drop-outs at time point 3 (p = .03, d = 0.26). Measures Appreciation. Appreciation was measured with a scale composed of two subscales with 5 items each referring to appreciation from supervisors and from colleagues, respectively (Jacobshagen et al., 2008). Responses referred to the extent to which each item applied to the participants’ work situation over the past 2 months on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). Cronbach’s alphas (Cronbach & Webb, 1975) for the supervisor-scale were .91 for the first time point (t1), .92for the second and third time point (t2, t3). For the colleagues-scale, Cronbach’s alphas were .86 for t1, .89 for t2 and .91 for t3. Illegitimate tasks. Illegitimate tasks were measured with the eight-item Bern Illegitimate Tasks Scale (BITS; Semmer et al., 2015). The introduction “Do you have work tasks to take care of, which ...” is followed by statements like ... keep you wondering if they have to be done at all?” for unnecessary tasks, and “... you believe should be done by someone else?” for unreasonable tasks. Answers ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (frequently); internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for unnecessary tasks was .84 for t1, .89 for t2, and .87 for t3. For unreasonable tasks, internal consistency was .85 for t1, .90 for t2 and .84 for t3. Social support. Social support was measured using the German adaptation (Frese & Zapf, 1987) of the social support scales by Caplan et al. (1975). Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .72 for t1, .73 for t2, and .74 for t3. Well-being. Well-being was measured with Warr’s (1990) instrument on job-related affective well-being. Participants indicated how often during the past two months their job made them feel each of twelve moods, such as “depressed”, “miserable”, “cheerful”, and “enthusiastic”. Three items each referred to enthusiasm (high arousal pleasant affect), contentment (low arousal pleasant affect), depression (low arousal unpleasant affect), and anxiety (high arousal unpleasant affect). Responses ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Cronbach’s alphas for enthusiasm were .85, .86, and .83 for t1-t3 respectively. For contentment the alpha values were .87, .85, and .84, for depression .85 for t1 and .88 for t2 and t3. For anxiety internal consistency was .80 for t1, .73 for t2, and .70 for t3. Analytical Procedure Our data has a three-level structure with measurement waves (Level 1) nested within persons (Level 2), nested in companies (Level 3). To estimate intra-individual as well as inter-individual effects, we analyzed the data with a multilevel structural equation model, using Mplus version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2015). As analyses yielded no significant differences between the organizations, we simplified the initial three-level model to a two-level model. On the within level, predictors were “latent group mean centered”, correcting for sampling error (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2015, p. 243). Significant coefficients on the within level reflect the effect of participants being high or low relative to their own mean for the respective predictor variable across the three waves. The reliability of the aggregated data was estimated by applying the Spearman-Brown formula (Lüdtke et al., 2008). Full information maximum likelihood procedures for two-level SEM were used deal with missing data. We first estimated a measurement model. For appreciation, appreciation by supervisors and appreciation by colleagues were used as indicators, applying the strategy of facet-specific parcels (Little et al., 2013). Similarly, unnecessary and unreasonable tasks were used as indicators for illegitimate tasks (Semmer et al., 2015). For affective well-being, we followed Warr et al. (2014) and used their four factors, enthusiasm, contentment, depression, and anxiety, as separate constructs. Subsequently, we estimated two structural models. Model 1 included appreciation and illegitimate tasks as predictors of the four well-being variables as main effects; Model 2 also included the buffering effect of appreciation on well-being. As social support is conceptually close to appreciation and might be suspected to be actually responsible for the effects of appreciation, we controlled for social support. We saw no theoretical reason for age and gender, two frequently controlled variables (see Spector & Brannick, 2011). As readers might wonder if age and gender do have an effect, however, we also ran our analyses controlling for them. Results did not change, and we report them without age and gender. Regarding power, our sample size is rather large at the between-level (n > 300) but rather small at the within-level (n = 3), which is more important. “As a general rule of thumb, increasing the sample size at the highest level ... will do more to increase power than increasing the number of individuals in the groups” (Scherbaum & Ferreter, 2009, p. 352). Furthermore, the self-report nature of this research design called for a statistical analysis that tests for common method bias. The Harman’s single-factor test, using the maximum likelihood method, was applied. This Harman’s single factor test showed that the covariance was less than 46%. This value is below the 50% cutoff typically employed and far from the 70% that would be needed to indicate a serious danger of common method bias in our kind of data, as determined by way of a simulation by Fuller et al. (2016). Thus, common method bias was not a serious threat to our findings. The poor data fit of a one-factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) also corroborates the lack of serious common method bias: chi-square = 1641.87, df = 36, RMSEA =.11, CFI =.94. Measurement Model A measurement model containing seven constructs – appreciation, illegitimate tasks, the four constructs of job-related affective well-being, and social support – across the three waves fitted well (χ2/df = 1.84, RMSEA = .03, CFI = .99, SRMRwithin = .025, SRMRbetween = .022) and constraining the factor loadings to be equal over time did not significantly affect the model (χ2/df = 1.88, RMSEA = .03, CFI = .99, SRMRwithin = .026, SRMRbetween = .024, χ2 difference test, Satorra-Bentler scaling correction, p > .05) (Satorra, 2000). Descriptive Results Table 1 contains means, standard deviations, and correlations on the between and within levels for all variables used in the analyses. Table 1 Means (M), Standard deviations (SD), and Correlations of the Study Variables   Note. Correlations below the diagonal reflect between-person associations of the level 2 variables (person; n = 307). Correlations above the diagonal reflect the within-person associations of the level-1 variables (measurement; n = 763). For the between-person association, level 1 data were averaged across all three occasions. The null models revealed that 36% of the total variance resided between-person in anxiety, 47% in contentment, 61% in depression, and 67% in enthusiasm, indicating that a considerable part of the variance can be explained by within-person variations (between 33% and 64%), thus necessitating a multilevel analysis (Hox, 1998). Structural models. Table 2 shows the estimates of the associations between appreciation and illegitimate tasks with the four indicators of well-being, in term of main effects (Model 1, Figure 1) and interactions (Model 2, Figure 2). Table 2 Two-level Structural Equation Models Predicting four Facets of Affective Well-being   Note. B = unstandardized regression coefficient; SEB = standard error. Fit-indices Model 1: χ2/df = 2.01; RMSEA = .04; CFI = .94; SRMRwithin = .04; SRMRbetween = .05. Fit-indices Model 2: χ2/df = 2.33; RMSEA = .05; CFI = .93; SRMRwithin = .04; SRMRbetween = .05.0 Sample size: n = 763 measures (level 1) of n = 307 participants (level 2). *p < .05, **p < .01 (two-tailed testing). Figure 1 Two-level Latent Structural Equation Model (Model 1)   Boxes represent measured variables, whereas the circle is used to represent unobserved latent factors. Variable names are presented in plain font if they are not centered, in bold font if the variable is groupmean centered, and bold italic font if the variable is grand-mean centered. Unstandardized coefficients are presented. Model fit: χ2/df = 2.01; RMSEA = .04; CFI = .94; SRMRwithin = .04; SRMRbetween = .05 *p < .05, **p < .01 (two-tailed testing). Figure 2 Two-level Latent Structural Equation Model (Model 2)   Boxes represent measured variables, whereas the circle is used to represent unobserved latent factors. Variable names are presented in plain font if they are not centered, in bold font if the variable is group mean centered, and bold italic font if the variable is grand-mean centered. Unstandardized coefficients are presented. Model fit: χ2/df = 2.33; RMSEA = .05; CFI = .93; SRMRwithin = .04; SRMRbetween = .05. *p < .05, **p < .01 (two-tailed testing). Appreciation. Confirming our first hypothesis, appreciation was positively related to enthusiasm (H1a) and contentment (H1b), and negatively with depression (H1c) and anxiety (H1d) on the within-person level, and to three of the well-being variables (all except anxiety) on the between-person level (Table 2, Model 1). Thus, participants reported higher levels of well-being for periods in which they experienced more appreciation as compared to periods in which they experienced less (within-person effect). In a parallel fashion, participants experiencing high appreciation, as compared to other participants, reported higher levels of well-being on the between-person level for three of the four outcome variables. Thus, our hypotheses concerning main effects of appreciation were largely confirmed. Illegitimate tasks. Our hypothesis regarding main effects of illegitimate tasks was only partly confirmed. On the within-level, illegitimate tasks were significantly related to enthusiasm and contentment. With regard to the between-level, illegitimate tasks were significantly related in the expected direction to all four indicators of well-being: enthusiasm (H2a), contentment (H2b), depression (H2c), and anxiety (H2d). Thus, Hypothesis 2 was not confirmed with regard to within-person effects, but supported with regard to person effects. Interactions. The buffering effect that was postulated in Hypothesis 3 could be found on the within-person level for contentment and anxiety (H3a, H3d), but not for enthusiasm and depression (H3b, H3c). On the between-level, no buffering effect was found. These results disconfirm our hypothesis with regard to between-person effects, and partly confirm it for within-person effects. Simple slope analyses for the two significant interactions between illegitimate tasks and appreciation at the within level, displayed in Figures 3 and 4, revealed the expected pattern. Illegitimate tasks were associated with contentment (B = -0.33, t = -3.05, p = .01) and anxiety (B = 0.17, t=3.94, p < .01) only when appreciation was low, but not when appreciation was high (contentment: B = -0.04, t = 0.16, ns; anxiety: B = -0.16, t = -0.51, ns). Figure 3 The Association of Illegitimate Tasks and Anxiety under Conditions of Low (-1SD) versus High (+1SD) Appreciation on the Intra-individual Level. Blow = 0.17, t = 3.94, p < .01; Bhigh = -0.16, t = -0.51, ns).   Figure 4 The association of Illegitimate Tasks and Contentment under Conditions of Low (-1SD) versus High (+1SD) Appreciation on the Intra-individual level; Blow = -0.33, t = -3.05, p = .01; Bhigh = -0.04, t = 0.16, ns).   Regarding our research question, our results indicate a buffering effect of appreciation on the association between illegitimate tasks and well-being only on the within-person level, although only for two of the four well-being indicators. The fact that interactions occurred on the within-person level only is in line with our conjecture that illegitimate tasks are not easily discounted in social comparisons, due to their public nature. Social support as a control variable. Social support was never significant in the within-person analyses but there were two significant coefficients in the between-person analyses. We also tested a model comprising the interactions between illegitimate tasks and social support (rather than between appreciation and social support), none of these interactions were significant, with regression weights as well as standard errors being close to |.01| in all four cases. The main goal of this study was to analyze the effect of appreciation and illegitimate tasks on affective well-being, as well as the moderating effect of appreciation, taking both the between-person and the within-person level into account. Main effects were confirmed for appreciation for all four indicators of well-being at the within, and for three of the four indicators at the between levels. Main effects for illegitimate tasks were confirmed for all four well-being variables at the between-level, and for one at the within-level. In addition, for two of the well-being variables there was an interaction on the within-level, in that illegitimate tasks predicted contentment and anxiety if appreciation was low. Therefore, these results present a mixed picture. Main Effects and Buffering Effects at the Within and Between Person Level Direct effects of appreciation. Our results fully confirm the direct effects of appreciation on the affective well-being constructs (i.e., depression, enthusiasm, anxiety, and contentment), on the within-person, and largely (i.e., for three out of four) on the between-person level. The more appreciation participants experienced, the higher the levels of affective well-being, both with regard to temporal (within-person) as well as social comparisons (between-person). Two associations were qualified by an interaction (contentment, anxiety); both were on the within-person level. We hypothesized that main effects of appreciation would occur on both levels, and our results largely confirmed this prediction. There was only one outcome variable for which there was no main effect of appreciation, but for this outcome appreciation interacted with illegitimate tasks. These findings underscore the importance of appreciation for employee well-being, corresponding to its theoretically postulated importance for satisfying the need for a positive regard by important others (Leary, 1999, 2015). Appreciation responds to this need in a way that is especially clear and direct (Stocker et al., 2014). Our results are in line with the few studies investigating appreciation as a variable in its own right (e.g., Apostel et al., 2017; Bakker et al., 2007; Stocker et al., 2014). The positive effect of appreciation on affective well-being remained significant after controlling for social support, indicating that appreciation is indeed more than mere social support. The results therefore support the need for focusing specifically on appreciation, rather than treating it only as part of larger constructs (e.g., leadership, social support, organizational justice1). Direct effects of illegitimate tasks. Regarding illegitimate tasks, we could only partly confirm our hypothesis. On the between-person level, illegitimate tasks were significantly related to all four aspects of affective well-being. On the within-person level, there were two main effects and two interactions. That appreciation had a more pervasive effect in terms of main effects than illegitimate tasks is remarkable as, for once, good seems to be stronger than bad (see Baumeister et al., 2001). We attribute this strong effect to the fact that appreciation sends a clear and direct signal affirming the self, whereas this message is more indirect in the case of illegitimate tasks. Second, the results underscore that one cannot assume that the same mechanisms work at both levels, as appreciation can buffer the effects of illegitimate tasks on the within-person level only. This result pertains to our research question. We certainly have no full explanation for this pattern, but we feel that it may be important to consider the visibility of events involved in the two types of comparison, as outlined in the introduction. The buffering effect of appreciation. Following Baumeister (1996), we suggested in the introduction that events/circumstances that are publicly visible are not easily discounted, especially in inter-personal comparisons, that is, social comparisons. Aspects that might counter such effects (i.e., resources) should refer to publicly visible events as well, which limits the number of events/circumstances that are likely to be considered. Building on this argument, we surmised that “public” events are not as easily countered (i.e., attenuated) as more private events would be. By contrast, the standard for temporal comparisons is different, comparing current events or circumstances to earlier ones. In doing so, people may take many more events into account than in social comparisons, including many positive events that may attenuate the impact of a stressor. Many of these events may be private in the sense that they are only known to the person experiencing them. Therefore, the number of events that can buffer illegitimate tasks should be greater for temporal comparisons. Consequently, publicly visible events should have a greater chance to be buffered in within- as compared to between-people analyses. Combining these considerations, we suggested the following: as illegitimate tasks entail more visibility, and as social comparisons make visibility especially salient, illegitimate tasks cannot be easily buffered on the between-person level. By contrast, visibility should not be so salient in temporal, intra-individual comparisons, and the number of items that could be taken into account is greater. As a result, buffering effects would be more likely to occur on the within-person level. Our results confirm our theoretical considerations in that buffering effects occurred at the within-person level only, but the confirmation is only partial, as only two of the four possible interactions were found, which involved contentment and anxiety; as there was a main effect for enthusiasm, there was only one outcome variable for which we did not find any effect (depression). Although we regard power as adequate overall, it may be somewhat low for interactions, which are typically harder to detect. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that only main effects of illegitimate tasks surfaced in between-person analyses, whereas interactive effects were found in within-person analyses only. Obviously, at this point our considerations are rather speculative and even to the point they are correct they certainly do not portray the whole picture. But they may be one part of the puzzle, and we do believe that they are worth being considered in further research and theorizing. Theoretical Implications and Further Research Appreciation. Theoretically, our results underscore the importance of appreciation. Effects of appreciation were rather pervasive; main effects occurred at both levels, and appreciation buffered the effect of illegitimate tasks for two well-being variables on the intra-individual level. We attribute these pervasive effects to appreciation responding to the need for a positive regard by important others (Leary, 1999, 2015) in an especially direct way. Appreciation not only deserves being studied as a variable in its own right in future studies; it also seems possible that some of the effects of constructs that include appreciation, such as social support, can to some extent be explained by the appreciation component of these constructs (see Semmer et al., 2008). Future studies should therefore control for appreciation in order to determine its role among the components of constructs such as social support or interactional justice and should also investigate to what extent the facets of appreciation have a differential impact. Finally, research should investigate to which extent appreciation can buffer the effects of any stressor, or if such buffering effects are confined to stressors that also have strong implications for the self (e.g., failure experiences); the latter would correspond to the matching principle specified by de Jonge and Dormann (2006). Illegitimate tasks. Although their effects were not as pervasive as those of appreciation, our results demonstrate the importance of illegitimate tasks. As the concept is rather new, it is important to demonstrate its usefulness, and the current study adds to a small but growing body of studies showing illegitimate tasks to predict a number of well-being indicators on an inter-individual (e.g., Omansky, et al., 2016; Schmitt et al., 2015; Semmer et al., 2015) as well as on an intra-individual level (e.g., Eatough et al., 2016; Kottwitz et al., 2013; Pereira et al., 2014; Sonnentag & Lischetzke, 2017). We, therefore, conclude that having to carry out tasks that employees consider not appropriate deserves attention in future research. Similar to appreciation, we see the main features of illegitimate tasks in their effect on one’s (professional) self – boosting it in the case of appreciation, offending it in the case of illegitimate tasks (Semmer et al., 2015). However, in contrast to appreciation, which refers to rather clear and direct communications, illegitimate tasks convey a threat to self-esteem in a more indirect way. Their effects were particularly clear at the inter-individual level, and we attributed that to stronger effects under conditions of social comparison, which makes the issue of visibility especially salient. Effects on an intra-individual level were present in three out of four cases, but only once in terms of a main effect, whereas they were contingent on appreciation in two cases. Between- vs. within-person effects. As discussed in the introduction, the majority of research on stress and resources at work has relied on inter-individual effects, yet the results have often been interpreted in intra-individual terms. Our study shows that between-person and within-person effects may sometimes converge (in our case, when dealing with appreciation) and sometimes not (in our case, illegitimate tasks). We argued that visibility may be an important aspect in these processes in that highly visible events or circumstances are less easily discounted (and thus, buffered) than low-visibility events or circumstances, and we argued that such processes would favor main effects for inter-individual comparisons but buffering effects for intra-individual circumstances. Although these considerations are very tentative at this moment, they might help stipulate the development of theories concerning the likelihood of converging or diverging effects between and within individuals with regard to specific variables. Given that theoretical foundations for such predictions need more research, such developments would be highly desirable, and if our considerations help moving such attempts further, that would be a worthwhile contribution. Well-being concepts. Regarding well-being, we focused on affective well-being, which is more reactive to recent experiences than the evaluative component, which is represented by satisfaction (Diener et al, 2018; Tov, 2018). Thus, our study does not represent the full range of subjective well-being, not to speak of other well-being concepts, such as eudaimonic well-being (Heintzelman, 2018; Ryan & Deci, 2001; Ryff, 2018). Future research might focus on well-being in a more comprehensive sense. In focusing on affective well-being, we were interested in its specific aspects as specified by Warr et al. (2014). As suggested by a reviewer, an alternative model would treat well-being as a single latent construct. We tested such a model, and it confirmed the pattern we found in that appreciation predicted well-being at both levels (bwithin = 0.19, p < .05; bbetween = 0.21, p < .05), whereas illegitimate tasks predicted well-being only at the between-level (bwithin = .13, ns; bbetween = -0.30, p < .05). However, there was no interaction at the within-level; furthermore, social support was statistically significant at both levels (bwithin = 0.09, p < .05; bbetween = 0.20, p < .05). Both models had a similar fit. Clearly, further research with other (and larger) samples will be needed to clarify the implications of each of these two approaches. It should be noted, however, that neither approach is inherently more viable; one can be interested conceptually in lower-level constructs (in our case, enthusiasm, contentment, depression, anxiety) or in higher-level constructs (well-being). Both approaches can be appropriate, and aggregating scales to global constructs often has advantages in terms of reliability but may “obscure any distinctiveness” (Bagozzi & Edwards, 1998). Appreciation and illegitimate tasks in a wider context. The present research focused on one specific resource and one specific stressor. In a broader sense, however, our research relates to approaches dealing with what has been termed “decent work”, a concept developed by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and referring to universal values “such as freedom, fairness, and dignity” (Burchell et al., 2013, p. 15). Such an overarching approach to “good work” has a long history; for instance Quality of Working Life in the 1970s (e.g., Davis & Cherns, 1975), the socio-technical approach (e.g., Cherns, 1987; Mumford, 2006), the job-characteristics model (Hackman & Oldham, 1980; see Parker & Wall, 1998), or the Gallup-investigations on engaging conditions at work (e.g., Harter et al., 2010). Research on precarious work arrangements (e.g., Howard, 2017), and the concept of Total Worker Health (Hudson et al., 2019) also might be mentioned in this context. More recently, the concept of sustainability has been incorporated, regarding sustainability “not only in terms of the ecological and socio-economic environment (...) but also in terms of improving the quality of life of every human being” and relating specifically to “well-being based on the enhancement of individual and organizational resources” (Di Fabio, 2017, p. 2). Di Fabio and Peiro (2018) have applied this concept to Human Capital Sustainable Leadership. By avoiding illegitimate tasks or, if that is not possible, offering acknowledgment and explanations (Minei et al., 2018), and thus preventing, or mitigating, offenses to the self, and by signaling appreciation, and thus acknowledging employees and their contributions, leaders as well as other organizational members can contribute to decent work. Furthermore, avoiding threats to, and offering affirmation of, the self implies respecting people’s dignity (Semmer et al., 2007), which relates to justice (Miller, 2001) and to organizational ethics (Sekera et al., 2014; Meier et al., 2013). Thus, the variables investigated in the current study are part of a broader picture that is captured by the concept of decent work. Practical Implications Three major practical implications can be drawn from the present findings. First, supervisors should consider to what extent tasks they assign are legitimate. If assigning illegitimate tasks is unavoidable (after all, organizational necessities may demand it), supervisors should show respect by acknowledging that a task may be considered illegitimate by the employee and by explaining why they assign the task nevertheless (“I know this is not your job, but...”). Corresponding to interactional fairness (Bies, 2015; Tyler, 2012), such explanations may “legitimize” the task assignment and thus avoid, or at least alleviate, its potential negative impact as recently shown in a study by Minei et al. (2018). Second, supervisors (and others in the organization), should realize the importance of appreciating others and their achievements. The finding by Stocker et al. (2014) pointed out about 0.9 “appreciation-events” per day indicating that expressing appreciation may not be very common in many organizations. Note that this does not imply giving indiscriminate positive feedback or ignoring poor performance, nor does it imply excessively praising people even for the smallest achievement. Appreciation can be expressed in many different ways. Thus, although praise seems to be the most frequent way for expressing appreciation, many behaviors qualify as well, such as communicating that one enjoys working with that person, assigning interesting tasks after good achievements, expressing trust (Stocker et al, 2014), granting good conditions at work (e.g., job control; Semmer et al., 2006), giving fair feedback (Bies, 2015), or listening attentively and showing genuine interest (van Quaquebeke & Felps, 2016). Third, supervisors should be aware that there are two standards of comparison that are likely to be relevant. One is the comparison with other people (“when John did the same thing, she was much more enthusiastic than when I did it”), the other is the comparison with previous experiences (“he does not seem to acknowledge my performance as much as he used to”). Sometimes it may be advisable to state the standard one is applying in order to avoid misunderstandings. Thus, someone receiving praise for a performance that was not very good, but better than usually, may misinterpret this praise as indicating good performance in general. Subtle differences in behavior may make quite some difference in these matters (Semmer, et al., 2016). Limitations and Strengths As in any study, several limitations have to be acknowledged. First, all data in this study were collected by means of self-report, implying the possibility of common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2012; Spector, 2006). We tested for this possibility and concluded that the common method bias was not a serious threat. Nevertheless, for future investigations of appreciation and illegitimate tasks, it would be useful to use additional sources of information (e.g., ratings by supervisors or other third parties). It should be noted, however, that statistical interactions, which are hard to find anyway (Aiken & West, 1991), are especially difficult to detect if common method variance is present (Siemsen et al., 2010), which lends credibility to our results. Second, we did not collect further information pertaining to the organization participants were working in. Future research should include such measures. Third, it is important to note that the study design does not allow conclusions concerning the causality of the effects, which may have been influenced by third variables not assessed in this study (Finkel, 1995). The main strength of our study is its focus on disentangling within-person and between-person effects and the combination of a stressor and a resource, both affecting the self. By showing that within- and between-person effects may be similar for some predictors, but different for others, our study can contribute to distinguishing the two processes and avoiding premature generalizations from one level to the other. Our attempts at explaining these differences in terms of visibility also may contribute to the development of theories about when processes can be expected to be similar or diverge. Regarding our predictors, we confirm the importance of illegitimate tasks, which constitutes a rather recent, but promising, stressor construct; furthermore, we can demonstrate the pervasive importance of appreciation, which we feel should receive more attention and deserves to be studied as a variable in its own right. Both, appreciation as well as illegitimate tasks, are part of overarching concepts such as decent work (Di Fabio, 2018). Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. 1 Concepts such as leadership and organizational justice typically include aspects such as appreciation (or similar terms, such as respect, or acknowledgment), but they do not typically regard it as a core element. It should be noted, however, that there are exceptions. Thus, van Quaquebeke and Eckloff (2010) present an instrument referring to respectful leadership; Semmer et al. (2008) show that emotional support, which refers to acknowledgment and esteem, is a core element of instrumental support as well; and Bies (2015) argues that human dignity is a core element of interactional justice. Cite this article as: Pfister, I. B., Jacobshagen, N., Kälin, W., Stocker, D., Meier, Laurenz L. & Semmer, N. K. (2020). Appreciation and illegitimate tasks as predictors of affective wellbeing: Disentangling within- and between-person effects. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 36(1), 63-75. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2020a6 Funding: This research was supported by the Swiss National Foundation Grant 100014_132318 / 17. References |

Cite this article as: Pfister, I. B., Jacobshagen, N., Kälin, W., Stocker, D., Meier, L. L., & Semmer, N. K. (2020). Appreciation and Illegitimate Tasks as Predictors of Affective Well-being: Disentangling Within- and Between-Person Effects. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 36(1), 63 - 75. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2020a6

isabel.pfister@psy.unibe.ch Correspondence: isabel.pfister@psy.unibe.ch (I. Pfister).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS