Aggregate Perceptions of Intrateam Conflict and Individual Team Member Perceptions of Team Psychological Contract Breach: The Moderating Role of Individual Team Member Perceptions of Team Support

[PercepciĂłn agregada del conflicto en equipo y de cada miembro del mismo a cerca de la ruptura del contrato psicolĂłgico de equipo: el papel moderador de la percepciĂłn de apoyo del equipo por parte de sus miembros]

Kevin S. Cruz1, Thomas J. Zagenczyk2, and Anthony C. Hood3

1University of Richmond, Richmond, VA, USA; 2Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA; 3The University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2020a7

Received 19 May 2019, Accepted 19 February 2020

Abstract

We seek to contribute to our very limited knowledge base about a relatively new type of psychological contract: team psychological contracts. We argue that aggregate perceptions of intrateam task and relationship conflict are positively associated with individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach. We also argue that individual team member perceptions of team support mitigate the respective relationships between aggregate perceptions of intrateam task and relationship conflict and individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach. Using 306 team members across 76 teams from 18 organizations, we find that aggregate perceptions of intrateam task and relationship conflict are both positively associated with individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach. However, we find that individual team member perceptions of team support only mitigate the relationship between aggregate perceptions of intrateam relationship conflict and individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Resumen

Pretendemos contribuir a nuestra muy limitada base de conocimiento sobre un tipo relativamente nuevo de contrato psicológico: el de equipo. Sostenemos que la percepción agregada de la tarea en el equipo y del conflicto en las relaciones se asocia positivamente con la percepción de la ruptura del contrato psicológico de equipo por parte de sus miembros. También sostenemos que la percepción de apoyo del equipo por parte de sus miembros mitiga la relación entre la percepción agregada de la tarea en equipo y del conflicto relacional y la percepción de los miembros individuales a cerca de la ruptura del contrato psicológico de equipo. Utilizando 306 miembros de 76 equipos de 18 empresas vimos que la percepción agregada de la tarea en equipo y del conflicto relacional se asocia positivamente a la percepción por parte de los miembros individuales de la ruptura del contrato psicológico de equipo. No obstante, vemos que la percepción de apoyo del equipo por parte de los miembros individuales solo mitiga la relación entre la percepción agregada del conflicto relacional en el equipo y la percepción de la ruptura del contrato psicológico de equipo por parte de sus miembros. Se abordan las implicaciones teóricas y prácticas.

Palabras clave

Contrato psicolĂłgico, Conflicto, Apoyo, Equipo, GrupoKeywords

Psychological contracton, Conflict, Support, Team, GroupCite this article as: Cruz, K. S., Zagenczyk, T. J., & Hood, A. C. (2020). Aggregate Perceptions of Intrateam Conflict and Individual Team Member Perceptions of Team Psychological Contract Breach: The Moderating Role of Individual Team Member Perceptions of Team Support. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 36(1), 77 - 86. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2020a7

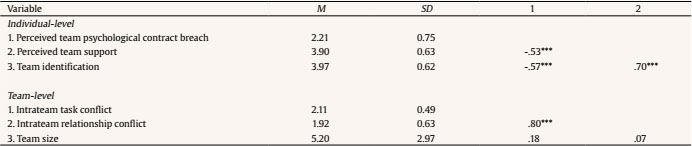

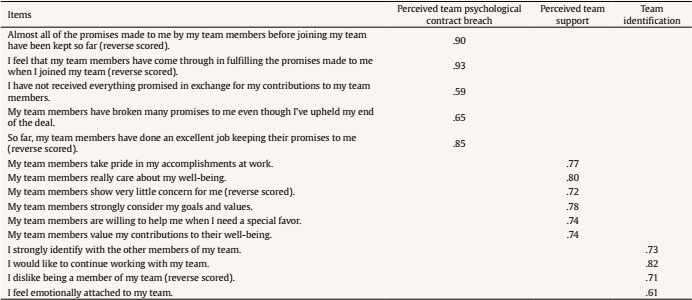

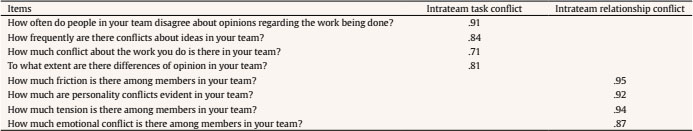

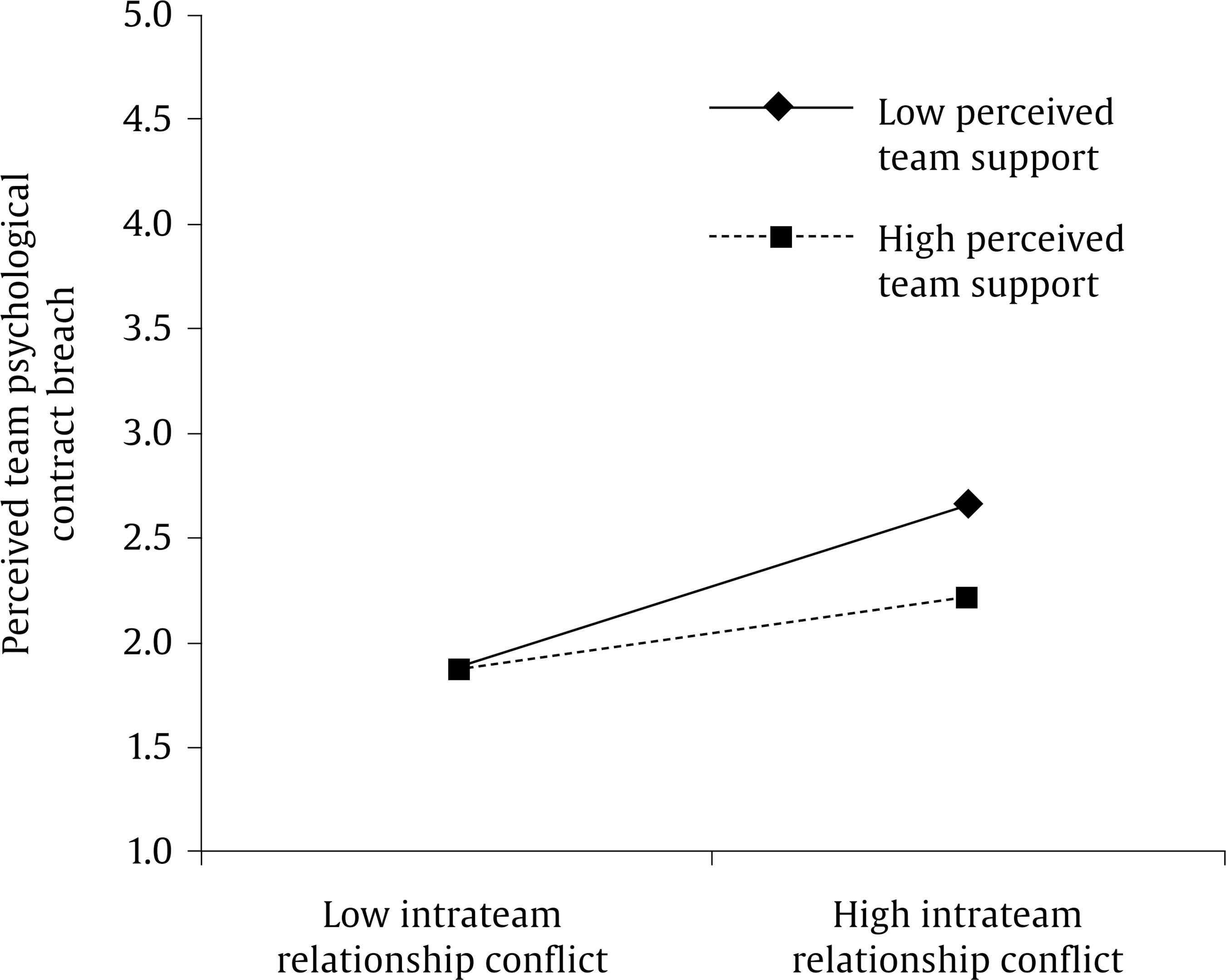

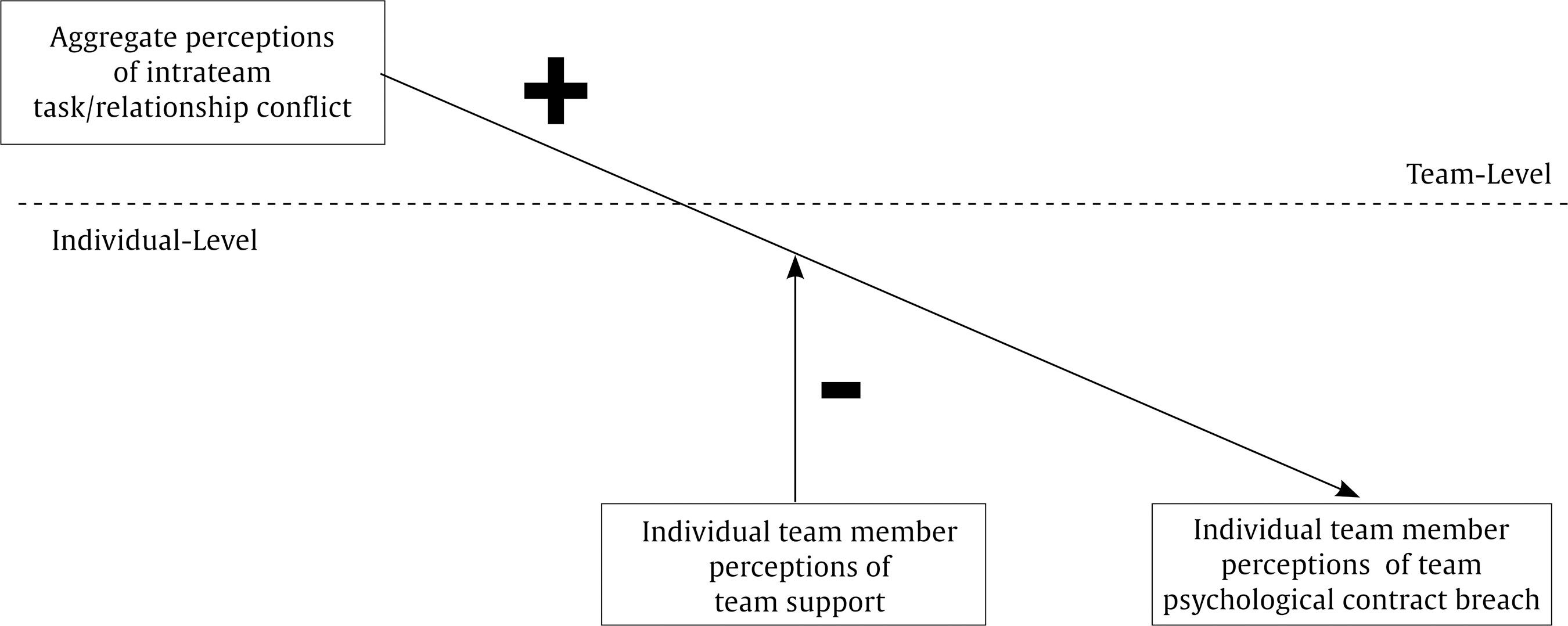

kevinscruz@yahoo.com Correspondence: kevinscruz@yahoo.com (K. S. Cruz).Today’s turbulent business environment, characterized by international competition and technological change, has resulted in dramatic and largely unfavorable changes to the employer-employee relationship (Jiang & Liu, 2015). These changes and the resulting consequences are often explained in terms of psychological contracts theory, which suggests that employees develop schemas related to what they perceive their organizations owe them with respect to promotions, development, and other factors, in exchange for their efforts on behalf of the organization (Rousseau, 1995, 2001). From a psychological contracts perspective, frequent change tends to result in psychological contract breach, which occurs when employees perceive that the organization has failed to fulfill its obligations to them (Morrison & Robinson, 1997). Breach is important because it causes employees to experience negative emotions that lead to a desire for revenge and, ultimately, counterproductive behavior and withdrawal (Coyle-Shapiro et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2007). Although research on psychological contracts has primarily focused on employer-employee relationships (Sverdrup & Schei, 2015), more recent research has extended psychological contracts to other workplace relationships, including supervisor-subordinate relationships (Bordia et al., 2010) and mentoring relationships (Haggard & Turban, 2012). These relationships require interactions between parties that often result in the development of psychological contracts (Rousseau, 1989). Teams, which are often designed by organizations in ways that increase autonomy and interdependence (Cruz & Pil, 2011), also require a great degree of interaction between members. Recent research has demonstrated that the interaction characteristic of a team results in the development of psychological contracts between team members and the team itself, in the same manner that employees develop psychological contracts with their organizations (e.g., Gibbard et al., 2017; Schreuder et al., 2017; Sverdrup & Schei, 2015). However, organizations often do not provide proper support systems for teamwork (Hackman, 2002). This can cause role ambiguity and ambiguous responsibilities (e.g., Beauchamp & Bray, 2001) within teams that create the potential for teams to have higher aggregate perceptions of intrateam conflict. Drawing on psychological contracts theory (Aselage & Eisenberger, 2003; Rousseau, 1995, 2001) and recent research on psychological contracts within team environments (e.g., Sverdrup & Schei, 2015), we argue that higher aggregate perceptions of intrateam conflict can signal that teams are not fulfilling promises and lead individual team members to perceive psychological contract breach by their teams. Additionally, we suggest that individual team member perceptions of team support, defined as the “degree to which employees believe that the team values their contribution and cares for their well-being” (Bishop et al., 2000), may play a key role in mitigating the potential effects of aggregate perceptions of intrateam conflict on individual team member perceptions of psychological contract breach by their teams. We suggest that this will occur because when employees perceive that others are supportive, they tend to give them the benefit of the doubt (or make situational attributions for conflict) and are thus less likely to perceive malicious intent (Aselage & Eisenberger, 2003; Dulac et al., 2008; Kiewitz et al., 2009; Lester et al., 2002). We test our hypotheses using a sample of 306 team members across 76 teams and 18 organizations. Theory and Hypotheses Psychological Contracts Theory Psychological contracts theory is based on the premise that when organizations fulfill unwritten promises to employees, employees will perceive that the employer cares for them and values their contributions (Coyle-Shapiro et al., 2019; Rousseau, 1995). The perceived promises that employees believe the organization is believed to make typically develop informally during recruitment, orientation, and through discussions with supervisors and peers (Rousseau, 2001). Organizations typically struggle to fulfill psychological contracts because they are inherently idiosyncratic in nature and situations arise as a result of factors beyond the control of the organization that make fulfillment difficult (Rousseau, 1989, 1995), even in cases when they put forth their best efforts to do so (Robinson & Morrison, 2000). Social exchange theory (Blau, 1964), and the reciprocity norm (Gouldner, 1960) that it is based on (Cropanzano et al., 2017), are commonly invoked by researchers to explain employee responses to psychological contract breach. From this standpoint, employers provide material and socioemotional benefits to employees in exchange for their efforts to help the organization achieve its objectives. The reciprocity norm (Gouldner, 1960) stipulates that employees are obligated to respond in kind to this favorable treatment provided by employers. However, psychological contract breach is generally regarded by employees as negative treatment, which often results in undesirable outcomes including decreased in-role and extra-role performance, less favorable job- and organization-related attitudes, and increased withdrawal cognitions and counterproductive behaviors (Coyle-Shapiro et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2007). As previously mentioned, more recent efforts have examined psychological contracts within the context of other vertical relationships, such as supervisor-subordinate relationships (e.g., Bordia et al., 2010) and mentor-mentee relationships (e.g., Haggard & Turban, 2012). This research generally shows that incorporating the role of psychological contracts helps to better explain outcomes. More recent studies have also explored the utility of the psychological contract construct within a team setting (e.g., Schreuder et al., 2017; Sverdrup & Schei, 2015). Studies in this vein are motivated in part by the manner in which organizations design and use teams. Teams are often designed and used in such a way that they are given responsibilities traditionally held by management (Cummings, 1978). This makes it possible that employees develop psychological contracts related to the treatment that they receive from their teams, and the way that teams are designed and used makes psychological contract breach a possible or even likely occurrence. Psychological contract breach in a team setting may be especially important because teams often have stronger effects on employee outcomes (relative to organizations) because employees tend to have higher levels of identification with their teams (van Knippenberg & van Schie, 2000). Aggregate Perceptions of Intrateam Conflict and Individual Team Member Perceptions of Team Psychological Contract Breach Sverdrup and Schei (2015) began investigating team psychological contracts by conducting an inductive investigation of joint operations in the Norwegian farming industry. A close examination of Sverdrup and Schei’s (2015) interviews with team members indicated that members of teams who reported relatively higher levels of intrateam conflict, or disagreements within their teams (Jehn, 1995), perceived higher levels of psychological contract breach by their teams. This suggests that aggregate perceptions of intrateam conflict may play a key role in shaping individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach and is therefore a focus of our study. An aggregate climate perspective is based on consensus among unit members of a focal construct (Chan, 1998) and it has been the most frequently examined perspective of intrateam conflict (Hood et al., 2017; Jehn et al., 2010). Teams research has largely focused on two forms of intrateam conflict: task conflict and relationship conflict. Task conflict occurs when disagreements exist within teams related to work tasks, whereas relationship conflict occurs when individuals have problems related to interpersonal relationships (Jehn, 1995). Intrateam task and relationship conflict may or may not co-occur to the same degree (De Dreu & Weingart, 2003; de Wit et al., 2012; O’Neill et al., 2018) and we therefore follow the intrateam conflict literature by treating these forms of conflict as distinct. Meta-analytic findings, based on aggregate climate perspectives, indicate that both forms of conflict are negatively related to team member satisfaction and team performance (De Dreu & Weingart, 2003), as well as trust, commitment, identification, and organizational citizenship behaviors (de Wit et al., 2012). We adopt this same aggregate climate perspective of intrateam conflict in our study because we believe a relatively high consensus among team members regarding perceptions of intrateam task and relationship conflict can influence individual team member perceptions of psychological contract breach by their teams. Sverdrup and Schei (2015) found that individual team member perceptions of reciprocal obligations played a key role in individual team member perceptions of intrateam conflict. Perceived reciprocal obligations are instrumental to understanding individual team member perceptions of psychological contract breach by teams because psychological contracts are based on social exchange and the reciprocity norm (Aselage & Eisenberger, 2003; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Social exchange refers to interactions in which giving and receiving material or socioemotional resources is contingent upon the expectation of return or reciprocity in the future (Blau, 1964; Homans, 1974). We believe aggregate perceptions of intrateam conflict, whether it is task or relationship conflict, can be interpreted by team members as a general signal of team members not fulfilling perceived reciprocal obligations, leading to individual team member perceptions that promises have not been fulfilled. Although we argue that aggregate perceptions of intrateam task and relationship conflict are both positively associated with individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach, we leave open the possibility that the magnitude of the effect of each form of conflict may be different (e.g., De Dreu & Weingart, 2003; de Wit et al., 2012). We therefore hypothesize: Hypothesis 1a: Aggregate perceptions of intrateam task conflict are positively associated with individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach. Hypothesis 1b: Aggregate perceptions of intrateam relationship conflict are positively associated with individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach. The Moderating Role of Individual Team Member Perceptions of Team Support Bishop et al. (2000) drew on organizational support theory in their introduction of the perceived team support construct. Organizational support theory (Aselage & Eisenberger, 2003; Kurtessis et al., 2017; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002) suggests that (un)favorable treatment by the organization is perceived by employees as the degree to which the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being. Similar to psychological contracts theory, organizational support theory draws on social exchange (Blau, 1964) and the reciprocity norm (Gouldner, 1960) to suggest that employees who feel supported feel obligated to reciprocate by holding attitudes and engaging in behaviors that help the organization (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). Just as we argued that individual team members form perceptions of psychological contract breach by their teams, Bishop et al. (2000) argued that team members form perceptions of support from their teams because teams take responsibility for many of the functions otherwise assigned to management. Self et al.’s (2005) finding that support from a work group is substantively different than support from an organization supported Bishop et al.’s (2000) arguments. Organizational support theory argues that perceptions of support, like support from a team, can form and exist irrespective of whether promises have been fulfilled or breached (Aselage & Eisenberger, 2003). Empirical research on perceptions of support and breach demonstrate that the two constructs are distinct, can co-exist, and are often inversely related (cf. Coyle-Shapiro & Conway, 2005; Kiewitz et al., 2009; Tekleab et al., 2005). Importantly, research examining organizational support indicates it can be an important buffer to negative outcomes (e.g., Duke et al., 2009; Scott et al., 2014). That is, when employees perceive that they have greater support, they do not respond as negatively. In the context of our study, employees who believe that they have the support of their teams may not feel as strongly that their teams have breached a psychological contract with them as a result of aggregate perceptions of intrateam conflict. We therefore hypothesize: Hypothesis 2a: Individual team member perceptions of team support moderate the positive relationship between aggregate perceptions of intrateam task conflict and individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach in such a way that the positive relationship is weaker for team members who perceive a higher degree of team support. Hypothesis 2b: Individual team member perceptions of team support moderate the positive relationship between aggregate perceptions of intrateam relationship conflict and individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach in such a way that the positive relationship is weaker for team members who perceive a higher degree of team support. Figure 1 provides a summary of our hypothesized model. Data and Sample Similar to Cruz and Pinto’s (2019) examination of outcome and process focus in real teams, we utilized a cross-sectional study design. Spector (2019) argued that cross-sectional designs are appropriate under certain conditions. The first three conditions are (1) uncertainty as to whether independent and dependent variables covary, (2) not knowing the timeframe between independent and dependent variables, and consequently (3) the research being considered exploratory. We believe our study meets each of these conditions because the only other study we are aware of that directly or indirectly investigated our main effects did so in a qualitative manner (i.e., Sverdrup & Schei, 2015). The fourth condition is wanting to examine the potential effects of a naturally occurring independent variable. We believe our study meets this condition because the teams in our study very likely experienced intrateam conflict prior to our study. The last condition is ruling out alternative explanations. We began to do this with our use of statistical controls. Thus, we believe our study satisfies Spector’s (2019) conditions for appropriately using cross-sectional designs. We sought participation from team members in organizations of varying sizes and from varying geographic locations and industries to increase the external validity of our findings (e.g., Cruz & Pinto, 2019). Team members from 18 organizations, located in various regions of the United States, participated in this study. The median organization size was 56 employees and the mean organization size was 130 employees. One organization represented the food manufacturing industry, while the remaining 17 organizations represented service industries including advertising and marketing, business products and services, consumer products and services, education, financial services, government services, information technology services, logistics and transportation, retail, and telecommunications. To ensure consistency with respect to what was meant by a “team” within and across organizations (Appelbaum & Batt, 1994), organizational representatives (e.g., Chief Executive Officer, Chief Operating Officer, Human Resources Manager) were provided Cohen and Bailey’s (1997) definition of a team, which is a “collection of individuals who are interdependent in their tasks, who share responsibility for outcomes, who see themselves and who are seen by others as an intact social entity embedded in one or more larger social systems (for example, business unit or the corporation), and who manage their relationships across organizational boundaries”, as a reference point to identify teams. Although Cohen and Bailey (1997) did not indicate what constituted a “collection of individuals,” Salas et al. (2009) indicated that a team consists of two or more individuals and we therefore allowed teams of two or more individuals to participate in this study. Using this definition and team size parameter, organizational representatives identified 91 teams, encompassing 458 team members, as participants. Organizational representatives provided a breakdown of the participating teams in their respective organizations by identifying teams by number and how many individuals were members of each team (e.g., Team 1: 3 members, Team 2: 4 members). The first author then mailed survey packages to the organizational representatives, which included paper surveys and self-addressed postage-paid envelopes organized by team (according to the previously provided team breakdown). The paper surveys included numerical codes so that surveys from members of the same team and organization could later be matched together. The organizational representative distributed the surveys and self-addressed postage-paid envelopes to the respective team members. The team members completed their respective surveys and mailed them directly back to the principal investigator in the envelopes. Responses were received from 325 team members (71% response rate) across 86 teams (95% response rate). Following Cruz and Pinto (2019), missing values in multi-item scales were replaced with the respective mean of the remaining scale items if the multi-item scales had 25% or fewer items with missing values (8 cases). Cases that did not meet this threshold were removed from the final sample. Teams with less than two respondents were also removed from the final sample. The final sample consists of 306 team members across 76 teams. The number of respondents per team ranges from 2 to 15 (team size ranges from 2 to 17; 9 teams had a team size of 2), with a mean of 4 respondents per team (mean team size is 5). Individual-Level Measures Individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach. Similar to prior research on psychological contract breach (e.g., Bordia et al., 2010; Cruz et al., 2018), we wanted a global measure of perceived team psychological contract breach and therefore used an adapted version of Robinson and Morrison’s (2000) 5-item measure (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The primary adaption was changing the focus from the organization to the team. Sample items include “I have not received everything promised in exchange for my contributions to my team members” and “So far, my team members have done an excellent job keeping their promises to me” (reverse scored). Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .89. Individual team member perceptions of team support. Similar to Bishop et al. (2000), we measured perceived team member support using a shortened and adapted version of Eisenberger et al.’s (1986) perceived organizational support scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). We used the same six items used by Shanock and Eisenberger (2006) in their investigation of perceived organizational and supervisor support. The primary adaption was changing the supporting party from the employer to the team. Sample items include “My team members really care about my well-being” and “My team members value my contributions to their well-being.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .89. Control variables. We controlled for variables that might have been theoretically related to individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach (Bernerth & Aguinis, 2016). At the individual-level, Restubog et al.’s (2008) research indicates that psychological contract breach is associated with organizational identification. Moreover, van Knippenberg and van Schie’s (2000) research indicates that individuals identify more strongly with their teams than with their organizations. These combined streams of research suggest that team members who identify strongly with their teams may perceive lower levels of team psychological contract breach. We therefore controlled for team identification using van der Vegt et al.’s (2003) 4-item team identification scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). A sample item is “I feel emotionally attached to my team.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .801. Team-Level Measures Aggregate perceptions of intrateam task conflict. Similar to Schabram et al. (2018), we followed Chan’s (1998) referent-shift model in order to ensure that our measure of intrateam task conflict corresponded to our theory. We did this by aggregating team members’ perceptions of the degree of task conflict within their teams as a whole (i.e., not with or between specific team members). Intrateam task conflict was measured using an adapted version of Jehn’s (1995) 4-item measure of intragroup task conflict (1 = none to 5 = a lot). The adaption was changing the referent from the work unit to the team. Sample items are “How often do people in your team disagree about opinions regarding the work being done?” and “How frequently are there conflicts about ideas in your team?”. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .86. Aggregation was supported by theory (Snijders & Bosker, 2012), significant between-team differences, χ2(75) = 133.41, p < .001, an ICC(1) value of .17, and a mean rwg(j) of .85. Aggregate perceptions of intrateam relationship conflict. To ensure that it matched our theoretical arguments, we measured intrateam relationship conflict in the same way as we measured intrateam task conflict. We did this by aggregating team members’ perceptions of the amount of relationship conflict within their teams as a whole (i.e., not with or between specific team members). Intrateam relationship conflict was measured using an adapted version of Jehn’s (1995) 4-item measure of intragroup relationship conflict (1 = none to 5 = a lot). The adaption was changing the referent from the work unit to the team. Sample items are “How much friction is there among members in your team?” and “How much are personality conflicts evident in your team?”. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .90. Aggregation was supported by theory (Snijders & Bosker, 2012), significant between-team differences, χ2(75) = 216.89, p < .001, an ICC(1) value of .33, and a mean rwg(j) of .86. Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations   Note. Individual-level n = 306. Team-level n = 76. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Control variables. We controlled for team size because social relations within teams tend to suffer as teams increase in size (Aubé et al., 2011).2 Preliminary Analyses The nested nature of our data (team members nested within teams and teams nested within organizations) results in a violation of the independence assumption in ordinary least squares regression. Hierarchical linear modeling controls for this violation by using regression equations at multiple levels of analysis (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). In order to assess whether we should use a three-level model (i.e., team members nested within teams nested within organizations) or a more parsimonious two-level model (i.e., team members nested within teams), we conducted a one-way analysis of variance on individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach. There were no significant differences between organizations for individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach, χ2(17) = 26.36, p = .068. Following the recommendations of Raudenbush and Bryk (2002) and Snijders and Bosker (2012) regarding the use of more parsimonious multilevel models when warranted, we tested our hypotheses using the more parsimonious two-level model (i.e., team members nested within teams), in which we found significant differences between teams for individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach, χ2(75) = 128.25, p < .001. When conducting multilevel analyses, one can choose among three centering options for the predictor variables: uncentered, group mean centered, or grand mean centered (Aguinis et al., 2013; Hofmann & Gavin, 1998). Centering is recommended when scales have no meaningful value of zero (Aguinis et al., 2013). Uncentered and grand mean centered models produce equivalent models, whereas group mean centered models are not equivalent to uncentered or grand mean centered models (Kreft et al., 1995). We group mean centered our individual-level predictors and grand mean centered our team-level predictors to prevent confounding of our cross-level interactions with between-group interactions (Aguinis et al., 2013; Hofmann & Gavin, 1998). All reported models used restricted maximum likelihood estimation and robust standard errors. Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics and correlations for the individual- and team-level variables. The correlations are in the predicted direction, but some of the correlations may be considered relatively high and therefore indicative of several potential problems. The first potential problem is method variance influencing the relationships between our variables. There is debate as to whether method variance leads to inflated or deflated relationships, if it occurs at all (cf. Conway & Lance, 2010; Podsakoff et al., 2003; Spector, 2006; Spector et al., 2019). Spector et al. (2019) argued that the best way to control for potential method variance is to first develop theory about the potential sources of method variance for specific measures. Like most constructs (Spector et al., 2019), theory about the potential sources of method variance for our constructs of interest is very incomplete. We therefore followed the advice of Spector et al. (2019) to focus on reducing the potential effects of method variance through controls in our study procedures. We had team members mail their surveys directly back to the principal investigator, which should “make (respondents) less likely to edit their responses to be more socially desirable, lenient, acquiescent, and consistent with how they think the researcher wants them to respond” (Podsakoff et al., 2003). A more fundamental issue related to the potential problem of method variance is that our study is about team member perceptions, whether the perceptions are about themselves or their teams, and the only individuals that can accurately report on these perceptions are the team members themselves. Asking another source, such as supervisors, may not accurately capture the perceptions of team members, may lead to a biased portrayal of teams, and could lead to problems with uncommon method variance (Spector et al., 2019). Our approach of aggregating team member perceptions to assess intrateam conflict is consistent with others who have examined intrateam conflict (e.g., Jehn, 1995; Jehn & Mannix, 2001; Jehn et al., 2010). Aggregation should also help reduce any potential upward biasing effects of common method variance because aggregated perceptions of intrateam conflict are technically from a different source (i.e., teams as a whole) than our moderating and dependent variables (i.e., from individual team members) and aggregation “reduces error by averaging out random individual-level errors and biases” (Robinson & O’Leary-Kelly, 1998). As a whole, we believe this suggests that method variance is not a serious problem in our study, but we cannot rule out the possibility that it is effecting our relationships in unidentified ways. A second potential problem is that team members and teams did not perceive substantive differences between our constructs of interest. We conducted three confirmatory factor analyses in order to assess whether this was a problem with our individual-level constructs. A three-factor model (i.e., all items loading on their respective latent constructs with the latent constructs being allowed to freely covary with each other), χ2(87) = 228.36, CFI = .95, SRMR = .05, fit better than a two-factor model (i.e., perceived team support and team identification items loading on one latent construct and perceived team psychological contract breach items loading on a second latent construct with the latent constructs being allowed to freely covary with each other), χ2(89) = 318.30, CFI = .92, SRMR = .06, and a one-factor model (i.e., all items loading on one latent construct), χ2(90) = 825.20, CFI = .73, SRMR = .10. Table 2 reports items and their respective standardized regression weights for the three-factor model. Given the high correlation between intrateam task and relationship conflict, r = .80, p < .001, we did the same for these team-level constructs. The fit indices for a two-factor model, χ2(19) = 56.22, CFI = .94, SRMR = .06, indicated a better fit than for a one-factor model, χ2(20) = 93.53, CFI = .88, SRMR = .07. Table 3 reports items and their respective standardized regression weights for the two-factor model. These results are in line with prior research that has found intrateam task and relationship conflict to be two separate, but related, constructs (e.g., Jehn, 1995, 1997). These results suggest that team members and teams perceived these constructs as substantively different. Table 2 Individual-Level Confirmatory Factor Analysis Final Model Items and Standardized Regression Weights   Note. N = 306 Table 3 Team-Level Confirmatory Factor Analysis Final Model Items and Standardized Regression Weights   Note. N = 76 A third potential problem is multicollinearity. At the individual-level, we found the highest variance inflation factor was 1.97, indicating multicollinearity is not a problem with our individual-level variables (Hair et al., 2006; Kutner et al., 2005). However, the same cannot be said for our team-level variables. Yu et al. (2015) found that multicollinearity increases in hierarchical linear models when correlations increase from .70 to .90 and when high correlations are between only level-2 predictors. These conditions are similar to the conditions that exist in our hierarchical linear model. As a result, we followed the approach of Hood et al. (2017) by testing the effects of intrateam task and relationship conflict on individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach separately to reduce concerns regarding multicollinearity, and to facilitate assessment of the unique effects of each type of intrateam conflict. 3 Table 4 reports our hierarchical linear modeling results. Models 1 and 2 test Hypotheses 1a and 1b, respectively. We find that aggregate perceptions of intrateam task conflict, γ = .59, SE = .09, p < .001, and intrateam relationship conflict, γ = .45, SE = .08, p < .001, are both positively and significantly associated with individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach. Hypotheses 1a and 1b are therefore supported. Models 3 and 4 test Hypotheses 2a and 2b, respectively. We find that the interaction between aggregate perceptions of intrateam task conflict and individual team member perceptions of team support, γ = -.30, SE = .22, p = .170, is not significantly associated with individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach. Hypothesis 2a is therefore not supported. However, we find that the interaction between aggregate perceptions of intrateam relationship conflict and individual team member perceptions of team support, γ = -.36, SE = .17, p = .034, is significantly associated with individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach. We graphed (see Figure 2) the form of this significant cross-level interaction by using +/- one standard deviation for the group mean centered variable of perceived team support and the grand mean centered variable of intrateam relationship conflict (Dawson, 2014). A simple slopes test indicated slopes were significant for team members one standard deviation below the mean, γ = .64, p = .000, and one standard deviation above the mean, γ = .27, p = .029, for perceived team support. Thus, Hypothesis 2b is supported. Table 4 Hierarchical Linear Modeling Results of Aggregate Perceptions of Intrateam Task and Relationship Conflict, and Individual Team Member Perceptions of Team Support, on Individual Team Member Perceptions of Team Psychological Contract Breach   Note. Individual-level n = 306. Team-level n = 76. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Figure 2 Interaction between Aggregate Perceptions of Intrateam Relationship Conflict and Individual Team Member Perceptions of Team Support.   Our results suggest that higher levels of aggregate perceptions of intrateam task and relationship conflict lead individual team members to more strongly perceive higher levels of psychological contract breach by their teams. Our results also suggest that aggregate perceptions of intrateam task conflict have a stronger effect than aggregate perceptions of relationship conflict. Although we do not find that individual team member perceptions of team support mitigate the effect of aggregate perceptions of intrateam task conflict, we do find that individual team member perceptions of team support do mitigate the effect of aggregate perceptions of intrateam relationship conflict. We believe these findings have several important theoretical implications. Theoretical Implications Team psychological contracts are a relatively new and understudied area (Gibbard et al., 2017). The few studies that have examined psychological contracts within teams have utilized an inductive approach of a relatively small sample of teams (e.g., Sverdrup & Schei, 2015) or examined them within student teams (e.g., Gibbard et al., 2017; Schreuder, et al., 2017). We are one of the first studies we are aware of to deductively examine team psychological contracts in a relatively large and diverse sample of organizational teams, thereby demonstrating the external validity of team psychological contracts, and breach in particular. We also add to this new area of study by demonstrating that an interpersonal team process that exists in nearly all organizational teams to some degree, intrateam conflict, may play a critical role in individual team member perceptions of psychological contract breach by their teams. Not only do our results add to our very limited knowledge base about team psychological contracts, our findings also contribute to the growing body of research demonstrating that organizations need to be cognizant of the fact that employees can form perceptions of psychological contract breach from many different entities within the workplace and they need to be managed accordingly because of the possible trickle-down effects they may cause. For example, Bordia et al.’s (2010) research found supervisors’ perceptions of organizational breach led to subordinates’ perceptions of supervisor breach, which led to lower customer satisfaction. Because of these possible trickle-down effects, we hope more researchers will see the value in better understanding team psychological contracts and how they may be interconnected to other aspects of the workplace. It may be that perceptions of team psychological contract fulfillment(breach) can help mitigate(exacerbate) other workplace perceptions, such as breach from organizations. In order to better understand individual team member perceptions of psychological contract breach by teams, we also heeded the advice of Aselage and Eisenberger (2003) by integrating individual team member perceptions of both team support and psychological contract breach. Our finding that individual team member perceptions of team support mitigated the positive relationship between aggregate perceptions of intrateam relationship conflict and individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach builds upon our scant knowledge of how perceptions of support and breach might impact each other (Suazo & Stone-Romero, 2011). We encourage future research to follow our lead, and the lead of others (e.g., Coyle-Shapiro & Conway, 2005; Kiewitz et al., 2009; Tekleab et al., 2005), by better integrating not only these social exchange constructs, but other social exchange constructs as well, so that we have a more nuanced understanding of social exchange in the workplace, and particularly, of psychological contracts. For example, we know that supervisors can have a particularly strong effect on employees, both negatively (see Tepper, 2007, for a review of abusive supervision) and positively (see Dulebohn et al., 2012, for a review of leader-member exchange). Investigating social exchange with team managers and how that may impact perceptions of team psychological contract breach may therefore be a fruitful area to begin this endeavor. Our results also have important implications for research on intrateam conflict. De Dreu and Weingart’s (2003) meta-analysis of intrateam conflict led them to predict that intrateam relationship conflict would have a larger impact on outcomes than intrateam task conflict. Their prediction was initially supported by de Wit et al.’s (2012) meta-analysis of intragroup conflict. However, our results suggest exactly the opposite for individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach. One reason that we might have found this effect is due to the high co-occurrence of aggregated intrateam task and relationship conflict perceptions that existed within the teams in our sample. Indeed, de Wit et al.’s (2012) moderator analyses revealed the exact pattern we found, for group performance and group member satisfaction, when task and relationship conflict were highly correlated. Whether this same pattern holds in teams in which there is not a high co-occurrence of perceived task and relationship conflict is an important empirical question that remains to be answered. O’Neill et al.’s (2018) work examining conflict profiles within teams may be a particularly fruitful area to begin answering this question. Practical Implications Managers need to be extra vigilant in managing aggregate perceptions of intrateam conflict because our results suggest individual team members’ stronger perceptions of team psychological contract breach may be another negative outcome that needs to be added to the long list of negative outcomes we already know to be associated with intrateam conflict (De Dreu & Weingart, 2003; de Wit et al., 2012). This may be especially true for aggregate perceptions of intrateam task conflict since we found it to be more strongly associated with individual team member perceptions of psychological contract breach by teams than aggregate perceptions of intrateam relationship conflict. Consultants and academics have offered many recommendations to help manage intrateam conflict, so we will not offer any additional recommendations here. What we will offer are recommendations that may help manage individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach that may be caused by aggregate perceptions of intrateam conflict. We know that perceptions of support and psychological contract breach are often inversely correlated with each other (e.g., Kiewitz et al., 2009; Tekleab et al., 2005), so trying to manage one will likely help manage the other. In terms of individual team member perceptions of team support, managers can explain to their team members ways in which their teams support them, even if there are relatively higher aggregate perceptions of perceived intrateam conflict. For example, managers can explain that there is a relatively high aggregate level of perceived intrateam task conflict because team members are trying to search for the best possible way to accomplish tasks in order to secure maximum financial incentives for their teams (assuming financial incentives exist). This can help team members realize that the ultimate goal of the conflict is for the well-being of their teams and fellow teammates and team members’ contributions to this process are therefore valuable. Similarly, managers can explain that intrateam task conflict is upholding implicit promises to team members to achieve the best possible task outcome. Explaining aggregate perceptions of intrateam relationship conflict is a bit tougher. Managers can explain to team members that they should not perceive a lack of support or greater breach from their teams if they are not the ones directly involved in the perceived relationship conflict. If team members are directly involved in the perceived intrateam relationship conflict, it is probably best for managers to revert back to recommendations of managing intrateam relationship conflict. These recommendations may help alleviate misconceptions team members may have about perceived intrateam conflicts and their possible impact on individual team member perceptions of psychological contract breach by their teams. Limitations and Directions for Future Research There are a number of limitations of our study that should be noted. First, we have a relatively small degree of internal validity. Although theoretically and methodologically imperfect, we did investigate whether we would find the same results by using aggregate perceptions of psychological contract breach as our independent variable and perceptions of team task and relationship conflict as our dependent variables and we found the moderation results to be substantively different. With this said, we encourage future research to attempt to show causality now that we have established that there are significant associations between our constructs of interest and that these associations have a large degree of external validity. Second, we chose to examine aggregate perceptions of intrateam conflict, which may not capture nuances that might exist in intrateam conflict. We encourage future research to adopt alternative approaches (e.g., an asymmetry approach; Jehn et al., 2010) to examining intrateam conflict in order to better understand how intrateam conflict may be associated with individual team member perceptions of team psychological contract breach. Third, we used teams from diverse organizations, but we did not collect information related to how these teams were designed across these diverse organizations. The impact of how teams are designed on our results is an important question that needs to be answered because team design may serve as important boundary condition of our results. Lastly, we did not collect data on perceptions of support and breach from other entities, like organizations or supervisors. It is conceivable that perceptions team members have about other entities may impact the degree to which individual team members perceive their teams as breaching psychological contracts with them and we therefore encourage future research to examine such possibilities. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Cruz, K. S., Zagenczyk, T. J., & Hood, A. C. (2020). Aggregate perceptions of intrateam conflict and individual team member perceptions of teampsychological contract breach: The moderating role of individual team member perceptions of team support. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 36(1), 77-86. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2020a7 Notes 1 Results were substantively the same when we controlled for individual team member perceptions of intrateam task and relationship conflict. 2 Results were substantively the same when we controlled for the respective team means of perceived team support. 3 Results were substantively the same when we simultaneously included aggregate perceptions of intrateam task and relationship conflict, and their respective interactions with individual team member perceptions of team support, in the same models. References |

Cite this article as: Cruz, K. S., Zagenczyk, T. J., & Hood, A. C. (2020). Aggregate Perceptions of Intrateam Conflict and Individual Team Member Perceptions of Team Psychological Contract Breach: The Moderating Role of Individual Team Member Perceptions of Team Support. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 36(1), 77 - 86. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2020a7

kevinscruz@yahoo.com Correspondence: kevinscruz@yahoo.com (K. S. Cruz).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS