Losing and Regaining Organizational Attractiveness During the Recruitment Process: A Multiple-Segment Factorial Vignette Study

[Ganar y recuperar atractivo organizacional durante el proceso de reclutamiento: un estudio factorial multisegmentario con viñetas]

Sabrina Krys and Udo Konradt

Kiel University, Kiel, Germany

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2022a4

Received 15 January 2021, Accepted 13 January 2022

Abstract

How applicants’ perceptions of organizational attractiveness (OA) change over the recruitment process and whether OA, once lost, can ever be regained, has hardly been investigated. Therefore, drawing on organizational justice and signaling theories, we examined the effects of treatment (fair vs. unfair), re-evaluation (positive vs. negative), and outcome (offer vs. rejection) on OA. Results from a multiple-segment factorial vignette study (N = 193 employees) showed a reduction in OA (67%) after applicants were treated unfairly. Up to 24% of this loss was regained in subsequent stages through positive re-evaluation and by being offered a job. The results also showed a reduction in OA (52%) for applicants who were treated fairly but re-evaluated their experience negatively and received a rejection. Thus, one good experience may not be enough to attract applicants, and understanding the combined effect of experiences is even more important than understanding the effect of a single experience.

Resumen

Apenas se ha indagado en cómo cambia la percepción del atractivo de la organización (AO) de los aspirantes a lo largo del proceso de reclutamiento y si puede recuperarse cuando se pierde. Así, partiendo de la justicia organizativa y de las teorías de la señalización analizamos el efecto del tratamiento (justo vs. injusto), reevaluación de las teorías de justicia organizacional (positiva vs. negativa) y resultados (oferta vs. rechazo) en el AO. Los resultados de un estudio factorial multisegmentario con viñetas (N = 193 empleados) mostraron una disminución del AO (67%) después de haber tratado a los aspirantes de modo injusto. Hasta un 24% de esta pérdida se recuperó en etapas posteriores gracias a una reevaluación positiva y a una oferta de trabajo. Los resultados igualmente mostraron una disminución del AO (52%) en los aspirantes a los que se trató de modo justo pero reevaluaron su experiencia negativamente y sufrieron rechazo. Así, una buena experiencia no garantiza que se atraiga a los aspirantes. Además, desentrañar el efecto combinado de las experiencias resulta aún más importante que explicar el efecto de una única experiencia.

Palabras clave

Atractivo de la organizaciĂłn, Justicia, Reclutamiento, Reacciones de los aspirantesKeywords

Organizational attractiveness, Fairness, Recruitment, Applicant reactionsCite this article as: Krys, S. and Konradt, U. (2022). Losing and Regaining Organizational Attractiveness During the Recruitment Process: A Multiple-Segment Factorial Vignette Study. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 38(1), 43 - 58. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2022a4

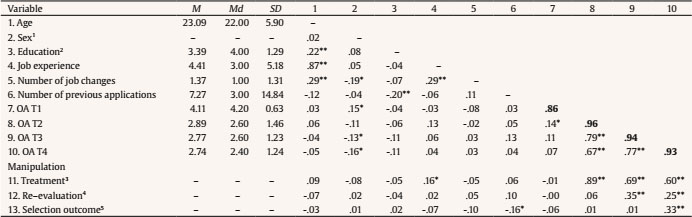

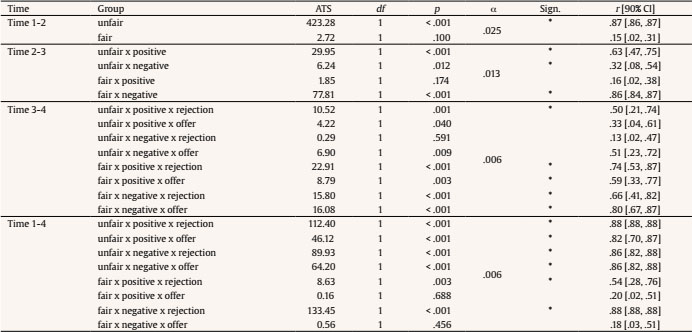

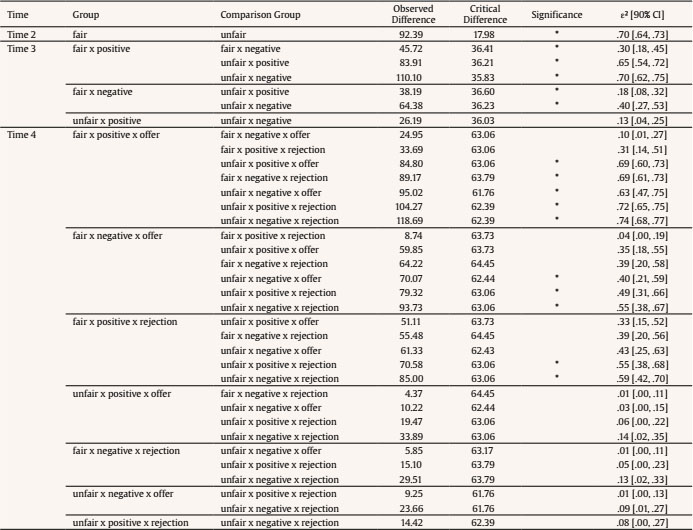

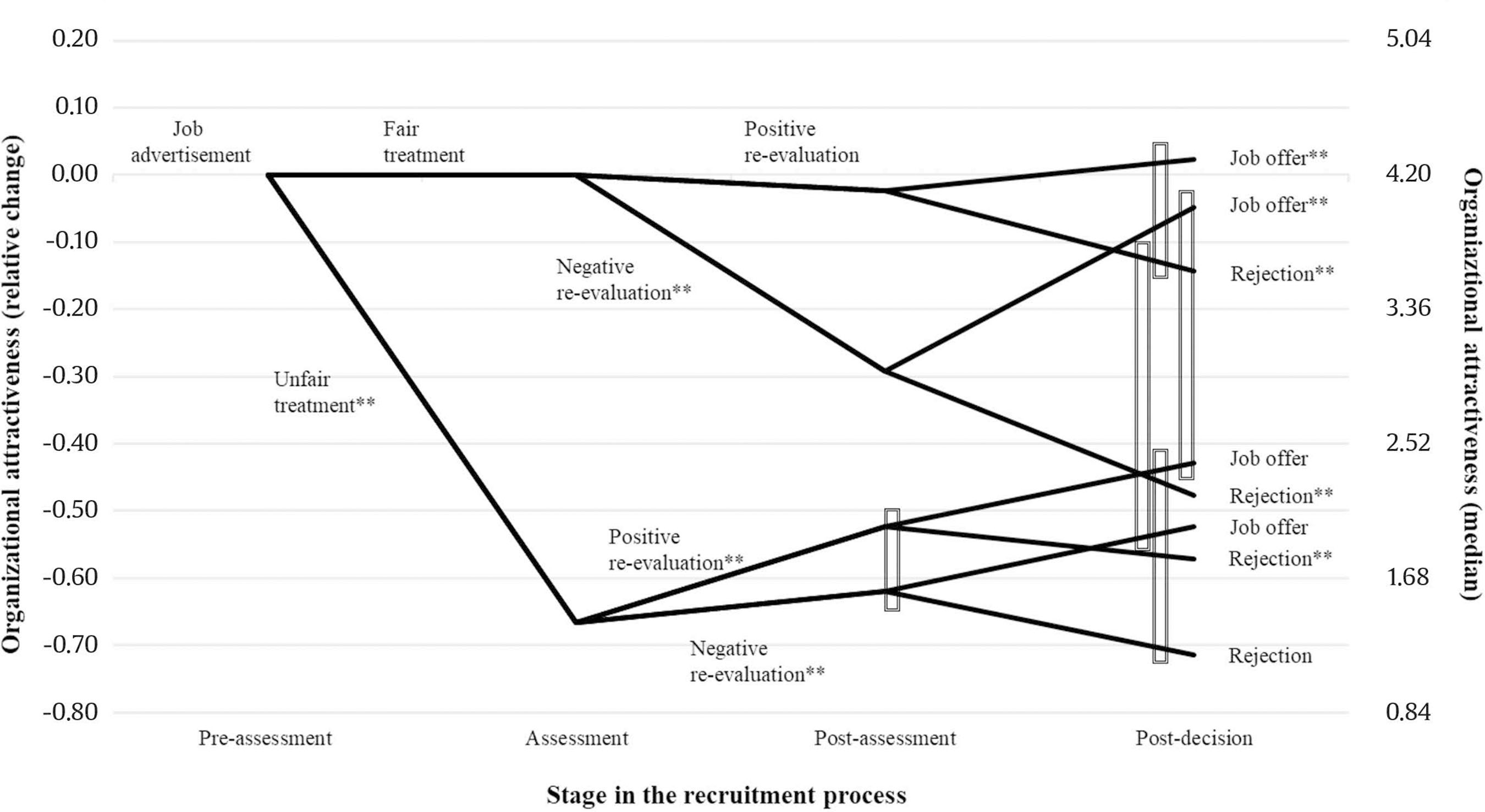

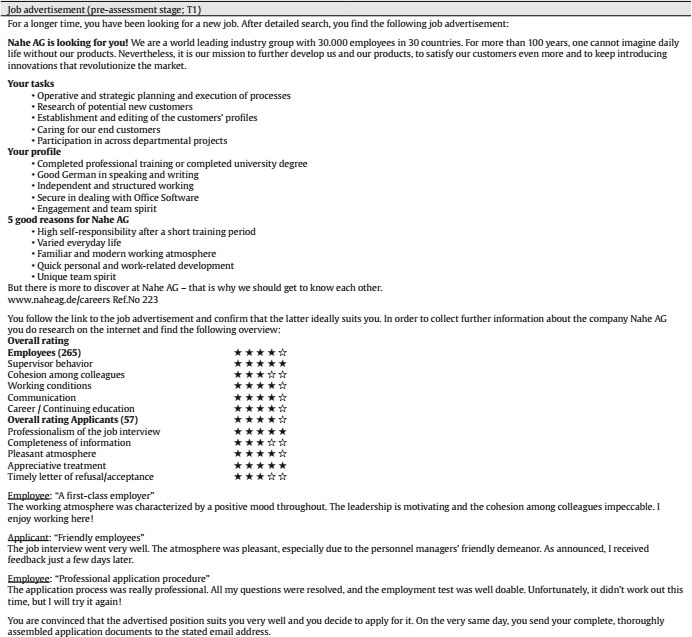

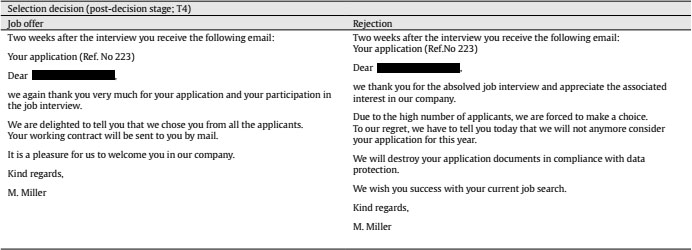

krys@psychologie.uni-kiel.de Correspondence: krys@psychologie.uni-kiel.de (S. Krys).Finding, attracting, and retaining qualified employees is crucial for business success (Chapman et al., 2005). Given the competitive nature of the business environment, it is beneficial for organizations to have a clear understanding of how job applicants react to what they experience during the recruitment process (e.g., McCarthy et al., 2017; Truxillo et al., 2017). Applicant reactions include applicants’ perceptions of an organization’s attractiveness (OA), also termed as applicant attraction, organization attraction, employer attraction or attraction to firm. OA has been described as “an attitude or expressed general positive affect toward an organization, toward viewing the organization as a desirable entity with which to initiate some relationship” (Aiman-Smith et al., 2001, p. 221) and can be conceived of as an applicant’s interest in pursuing employment with an organization (Evertz & Süß, 2017; Wilhelmy et al., 2019). Theory and research suggest that OA is a critical factor in attracting high-performing job seekers and affects the size and quality of the pool of applicants (Celani & Singh, 2011; McCarthy et al., 2017). During the recruitment process, applicants’ perceptions of OA may change as they receive new information (Breaugh, 2009; Evertz & Süß, 2017; Saks & Uggerslev, 2010). Despite the importance of this potential change in OA, previous research is limited in various respects. First, studies typically used a maximum of two measurement points, which does not reflect the multi-stage recruitment process and cannot fully capture the change in applicants’ reactions. Second, previous research has tended to focus on the early stages of the recruitment process (e.g., the interest or application stage; see, for example, Allen et al., 2007). This disregards the fact that organizations need to be able to retain highly talented people from the beginning of the recruitment process to the point where they are given a job offer (McCarthy et al., 2017), and that data collected at the beginning of the process does not necessarily reflect the status at the end of a recruitment process (Ryan & Delany, 2010). Third, when considering how applicant reactions change dynamically throughout the recruitment process, it is important to examine how applicants’ experiences affect their reactions at later stages, both individually, i.e., experiences are examined independently (e.g., how does unfair treatment affect OA at the subsequent stage of the recruitment process?) and in combination, i.e., experiences are examined dependently (e.g., how does unfair treatment affects OA at the subsequent stage of the recruitment process when applicants positively re-evaluate the process?; see Saks & Uggerslev, 2010). Accordingly, the fundamental purpose of the present study is to provide a nuanced understanding of OA by addressing two critical gaps in the literature on applicant reactions. First, it responds to calls for more research on changes in applicant reactions that unfold across the entire recruitment process (also including later stages in the process, such as the decision stage). Second, determining the extent to which OA may be affected by experiences at different stages would improve our understanding not only of their individual contributions but also their relative contributions. Factors that might be significant in explaining changes in OA include organizational practices such as fair or unfair treatment (Uggerslev et al., 2012), cognitive processes such as the re-evaluation of the experience (Jones & Skarlicki, 2013; Lind, 2001; Proudfoot & Lind, 2015), and decisions to offer a job or reject a candidate (Lilly & Wipawayangkool, 2018). We use a multiple-segment factorial vignette design with four repeated measures to examine how applicants’ experiences affect OA, both individually and in combination, and aim to examine whether OA lost at any stage can be regained at a later stage and how OA can be maintained throughout the recruitment process. In the following, we explain the underlying theories, describe the individual stages of a recruitment process in more detail, and derive the respective hypotheses. Literature Review and Hypotheses Recruitment can be defined as covering “all organizational practices and decisions that affect either the number, or types, of individuals that are willing to apply for, or to accept, a given vacancy” (Rynes, 1991, p. 429), and typically consists of several stages that applicants have to pass through to be offered a job (pre-assessment stage, assessment stage, post-assessment stage, and post-decision stage; Barber, 1998; Evertz & Süß, 2017). The multi-level integrative model of job search and employee recruitment developed by Acikgoz (2019) illustrates that during this multiple-stage or multiple-hurdle process applicants constantly receive new information, integrate it with their previous experience of that organization, and constantly re-evaluate their view of the organization throughout this process. In his review, Breaugh (2013) concluded that, at each stage, applicants gain new impressions of the organization triggered by recruiter behaviors and aspects of the recruitment process, and that applicants constantly try to gain a sense of what it would be like to work for the organization. For example, recruiter behaviors and aspects of the recruitment process may relate to compliance with the justice rules proposed by Gilliland (1993). In his influential model of applicants’ reactions to employment selection systems, attitudes towards the organization are mainly affected by the adherence to procedural and distributive justice rules. Procedural justice includes formal characteristics such as the opportunity to perform, explanations, and interpersonal treatment. Distributive justice relates to the fairness of the hiring decision itself. From a signaling theory perspective (Rynes, 1991; Spence, 1974; for an overview, see Celani & Singh, 2011), these impressions that applicants get during the recruitment process serve as cues, indicators or signals of unknown organizational attributes, from which applicants draw inferences about certain features of the organization (Highhouse et al., 2007). For example, a warm welcome at the beginning of the recruitment process may signal to applicants that they will be valued and treated well if hired (Breaugh, 2008). These experiences also trigger cognitive processes, such as the formation of fairness perceptions or re-evaluation of the experience, and applicants repeatedly ask themselves whether they would like to work for this organization (e.g., Breaugh, 2009; Evertz & Süß, 2017). Therefore, because recruitment involves both parties assessing one another, it can be conceived of as a dynamic decision-making process that extends over a longer period of time (Swider, 2013). A meta-analysis testing predictors of OA demonstrated that information received at one stage of the recruitment process affects applicant reactions at later stages (Uggerslev et al., 2012). It is important for organizations to recognize this, so that they can avoid practices that prevent applicants from withdrawing during the recruitment process, encourage applicants to accept a job offer, and encourage good applicants who have narrowly missed out on being appointed to reapply as further positions become available (Ryan & Delany, 2010; Saks & Uggerslev, 2010; Swider, 2013). Organizational Attractiveness during the Assessment Stage: Fair or Unfair Treatment Fairness plays a prominent role in shaping how attractive an organization is to individuals. Meta-analytic evidence suggests that applicants who perceived that they were treated fairly during the assessment stage were also more attracted to the job and the organization than those who were treated unfairly (Hausknecht et al., 2004; Uggerslev et al., 2012). During the assessment stage, applicants gain information and form impressions of their prospective employer (Wilhelmy et al., 2019), and the way they are treated during the assessment stage helps them to predict how they might be treated later, as an employer (Breaugh, 2008; Celani & Singh, 2011; Harold et al., 2016). This perspective, in which information received during the recruitment process are seen as signals of an organization’s attributes, is in line with relational models of procedural justice (see Chan, 2008), including the fairness heuristic theory of Lind (2001) and the group-value model of procedural justice of Lind and Tyler (1988). In these models, procedures reflect how an organization values its members: fair treatment conforms to applicants’ norms regarding social conduct, and not only signals appreciation and trustworthiness to applicants but also reassures them that their interests will be protected and promoted within the organization. If applicants are treated fairly, they may also perceive the organization as having a high reputation, see themselves as being of high value to the organization, and identify strongly with the organization (Tyler & Blader, 2003). This is also in line with the conceptual model of uncertainty reduction in recruitment (Walker et al., 2013), which proposes that fairness perceptions stemming from interactions during the recruitment process influence OA both directly and indirectly via applicants’ positive relational certainty; this makes applicants less uncertain about what organizational relations might be like when they join the organization. On the other hand, the aforementioned models suggest that applicants who are treated unfairly assume that their value is not appreciated and that they then expect similarly unfair treatment when they join the organization. According to the justice as deonance perspective, treating others fairly is the right thing to do simply because it is moral (for details see Folger, 2001). In other words, we often feel that we and others have a moral duty to behave fairly. Justice is thus seen as something done for its own sake (Cropanzano et al., 2016; Folger & Glerum, 2015). Supporting this perspective, Turillo et al. (2002) demonstrated that people consider a fair treatment to be a moral obligation and thus expect being treated fairly. Furthermore, people would most likely only apply for a job if the information they have up to that point (e.g., the job advertisement itself or rating portals) indicates that they will be treated fairly by that organization, implicating that applicants generally expect to be treated fairly in the recruitment process. The dynamic model of organizational justice (Jones & Skarlicki, 2013), which integrates several justice theories, describes a cyclical process in which judgments about an entity (e.g., the organization) undergo major changes or are largely maintained. Their model suggests that attitudes (e.g., OA) toward an organization tend to be relatively stable and resistant to change when there is convergence between our expectations of fair treatment and what we actually experience. However, when our experience seems inconsistent with those expectations, that can be a phase-shifting event, a change in attitude is triggered. Applied to the recruitment context, this would indicate that a significant change in OA is only likely when applicants’ experiences during the assessment stage are inconsistent with their prior expectations. Furthermore, and in line with the negative bias in the formation of impressions and evaluations (e.g., Baumeister et al., 2001), we also argue that unfair treatment has a greater impact on applicants’ attitudes than fair treatment. As noted above, there is a general expectation that people generally behave fairly because of social requirements and norms. In contrast, unfair behavior is more unexpected and therefore more salient when it is apparent. Furthermore, people may generally consider negative information to be more diagnostic of an entity’s character than positive information (Hamilton & Huffman, 1971). Applied to unfair treatment by a potential employer, this would indicate that unfair treatment would tell more about the employer than fair treatment. Conclusively, fair treatment that is consistent with prior expectations should not affect OA, whereas unfair treatment that contradicts the expectation of being treated fairly should lead to significant changes in OA. This would indicate that organizations can either help to ensure OA by acting fairly as applicants would expect or lose OA if they act unfairly. Thus, there should be a difference in OA between the pre-assessment and assessment stage for applicants who were treated unfairly (within-group comparison), and there should also be a difference in OA at the assessment stage between these applicants and those who were treated fairly (between-group comparison). We therefore hypothesize that: Hypothesis 1: Applicants will perceive the organization that is expected to act fairly as less attractive if they are treated unfairly in the assessment stage compared to applicants who were treated fairly. Organizational Attractiveness during the Post-Assessment Stage: Positive and Negative Reevaluation According to the dynamic model of organizational justice (Jones & Skarlicki, 2013), after people experience a situation in which they have been treated fairly or unfairly, their immediate reaction is generally followed by a process of cognitive re-evaluation (for an overview, see also Proudfoot & Lind, 2015). In the case of a recruitment process, applicants may cognitively process and reflect on how they have been treated during the assessment stage. Especially in situations that are important to people and have implications in terms of whether their core psychological needs will be met (e.g., getting a job) they expend more cognitive effort to re-evaluate events (Cropanzano et al., 2001; Johnson & Eagly, 1989; Weiner, 1995). Re-evaluation allows people to work out why the event occurred and to work out the possible future consequences of what has happened (i.e., make causal attributions), to compare this event to alternative scenarios (engage in counterfactual thinking), and to discuss it with others, such as family, friends or colleagues (see Jones & Skarlicki, 2013). Rethinking, discussing the experience with others, and comparing the experience to alternative scenarios might provide applicants with new information and perspectives on the process, which may affect the way they re-evaluate their previous experiences (Degoey, 2000; Jones & Skarlicki, 2013; Rupp, 2011). If applicants make a negative re-evaluation of the situation (for example comparing it with better alternatives, also known as upward counterfactual thinking; Byrne, 2016) and conclude that the organization should have behaved better, this can have an adverse effect on OA for those applicants, because they are likely to feel less valued (cf. Harold et al., 2016; Lind & Tyler, 1988). Hence, just because applicants were treated fairly does not mean that they do not reflect on their experience, share it with others, and possibly gain new insights into the situation (e.g., they shift their point of reference by discussing it with others). Especially if applicants have been treated fairly by the organization, negatively re-evaluating the experience should lead them to revise their attitude (Christianson, 2017), which should then reduce OA for those applicants. Conversely, if applicants have been treated “unfairly”, negatively re-evaluating one’s experience should not lead to any change in OA, because it will only confirm their existing view of the organization. Thus, there should be a difference in OA between the assessment and post-assessment stage for applicants who were treated fairly but negatively re-evaluated their experience (within-group comparison), and there should also be a difference in OA at the post-assessment stage between these applicants and those who were treated unfairly and negatively re-evaluated their experience (between-group comparison). Hypothesis 2a: Applicants who have been treated fairly in the previous stage of recruitment will perceive the organization as less attractive if they negatively re-evaluate their experience compared to applicants who have been treated unfairly. Positively re-evaluating one’s experience should only have a positive effect on OA to them if they have been treated unfairly (e.g., applicants explain away or justify what has happened; Jones & Skarlicki, 2013). When positively re-evaluating a negative experience (also known as downward counterfactual thinking; Byrne, 2016), applicants conclude that, even though they felt the treatment they received was unfair, the organization has probably acted appropriately in the circumstances (e.g., peers report even worse experiences, and from this perspective their own treatment seems fair, relatively speaking). This re-evaluation should bring the applicants’ values and standards and those of the organization closer together (cf. Breaugh, 2008; Harold et al., 2016). In turn, the applicants should change their attitude (Christianson, 2017), and should subsequently perceive the organization as more attractive. Conversely, if applicants have been treated “fairly”, positively re-evaluating one’s experience should not lead to any change in OA, because it will only confirm their existing view of the organization. Thus, there should be a difference in OA between the assessment and post-assessment stage for applicants who were treated unfairly but positively re-evaluated their experience (within-group comparison), and there should also be a difference in OA at the post-assessment stage between these applicants and those who were treated fairly and positively re-evaluated their experience (between-group comparison). Hypothesis 2b: Applicants who have been treated unfairly in the previous stage of recruitment will perceive the organization as more attractive if they positively re-evaluate their experience compared to applicants who have been treated fairly. Organizational Attractiveness during the Post-Decision Stage: Selection Outcome In the final stage of a recruitment process, the hiring decision applicants receive will have an impact on how attractive the organization is to them (McCarthy et al., 2017) and may even “wash out” previous unfair treatment or a negative re-evaluation (Maertz et al., 2004). According to relational models of procedural justice (Chan, 2008), people who receive a job offer should feel valued and an enhanced sense of self-esteem. This is also reflected in Gilliland’s (1993) justice model: adherence to distributive justice implies that the outcome is justified for the performance of the applicant and thus appreciates the applicant’s value. In contrast, getting a rejection would either mean that the outcome is not just or that the performance of the applicant was insufficient, which would represent a self-threat according to the self-threat model of procedural justice (Lilly & Wipawayangkool, 2018) and the applicant attribution-reaction theory proposed by Ployhart and Harold (2004). According to these theories a rejection thus represents a threat to the ego or self-concept, and applicants often have to restore their self-esteem by becoming defensive or making self-protecting external attributions (i.e., self-serving bias mechanism). They tend to seek other explanations for their failure and may blame the organization for their own performance (e.g., the method is irrelevant or not valid), regardless of whether the decision was fair. People therefore feel more responsible for a success than for failure and try to attribute this failure to external factors. Therefore, a self-serving bias may occur, especially when applicants receive a rejection. Ryan and Delany (2010) have aptly stated that applicants “do react more negatively to rejection, regardless of how well such a decision is couched” (p. 138). Research has demonstrated that for applicants who received a job offer the organization was more attractive at the end of the recruitment process than for those who were rejected (e.g., Schinkel et al., 2016; Schinkel et al., 2013). Stevens (2010) summarized that at least half of all applicants developed a negative attitude toward the recruiting organization after being rejected, and one fifth stopped buying its products as a result. This also emphasizes that applicants are potential customers, that recruitment experiences might be at least as damaging as customer experiences, and that the OA to potential employees can coincide its OA to potential customers. Conclusively, there should be a positive difference in OA between the post-assessment and post-decision stage for all applicants who were offered a job, and a negative difference in OA for all applicants who were rejected, regardless of the prior treatment and re-evaluation (within-group comparisons). Accordingly, we hypothesize that: Hypothesis 3a: When applicants receive a job offer, the organization will become more attractive to them, irrespective of whether they were treated fairly or unfairly during the recruitment process or negatively/positively re-evaluated their experience. Hypothesis 3b: When applicants are rejected for a job, the organization will become less attractive to them, irrespective of whether they were treated fairly or unfairly during the recruitment process or negatively/positively re-evaluated their experience. Participants Participants were recruited through personal and professional contacts in Germany. As an incentive, participants were awarded one of five $20 cash coupons after completing the study. One-hundred and ninety-four employees participated (mean age = 23.09 years, SD = 5.90) and 75.3% were female (5.7% missing). The mean educational level was 3.39 (SD = 1.29) on a scale ranging between 1 (low, general secondary school [Hauptschulabschluss in Germany]) and 6 (high, university degree). They had on average a job experience of 4.41 years (SD = 5.18) and the average number of job changes in the last five years was 1.37 (SD = 1.31). They had on average experience with 7.27 applications in the last five years (SD = 14.84). The size of the sample used for this study can be deemed to be adequate because the power was ≥ 90% (using the G*Power program; Faul et al., 2007) assuming a moderate effect size in the population (f 2 = .15; Cohen et al., 2003). Study Design and Procedure We used a multiple-segment factorial vignette design, which fits into the broader category of policy-capturing designs (Aguinis & Bradley, 2014; Karren & Barringer, 2002; Nokes & Hodgkinson, 2017), for several reasons. For example, policy capturing is an appropriate method to use to avoid ethical conflicts arising from fairness violations in real-life settings (Kiker et al., 2019). The scenarios and texts outlined the four stages of a fictional recruitment process: pre-assessment (T1, baseline), assessment (T2, fair vs. unfair treatment), post-assessment (T3, positive vs. negative re-evaluation), and post-decision (T4, job offer vs. rejection). The study thus consisted of a 1 x 2 x 2 x 2 between-subjects design with four repeated measurements of OA to participants (i.e., T1 to T4). In line with the design, participants were randomly assigned to one of the eight conditions.1 This design resulted in a total of 776 observations in the analyses. The eight experimental groups did not differ with respect to demographic variables. All procedures carried out in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution’s research committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki or comparable ethical standards. The participants were informed about the study and scientific practice. They gave their consent to the inclusion of material pertaining to themselves, on the understanding that they could not be identified via the paper, and that the data were completely anonymized. Participation in the study was voluntary and participants had the option to withdraw from the survey at any time. After giving informed consent, participants were asked to imagine they were applying for a job (adapted from the scenario manipulation used by Ployhart et al., 1999). For this purpose, all participants received the same fictitious job advertisement and corresponding positive evaluations from fictional applicants and employees (i.e., baseline measurement; T1). To avoid any potential confounding of the proposed effects with the participant’s own professional interests, we formulated the job description by referring to attributes of the organization (e.g., leading industry group, social responsibility, sustainability) and kept the description of the position neutral (e.g., it was only required that applicants must have a completed professional training or a university degree, but it was not specified). The process lasted approximately one hour in total. In line with best practice (Aiman-Smith et al., 2002; Nokes & Hodgkinson, 2017; Rotundo & Sackett, 2002), we also conducted a pilot study to validate the statements used in the scenarios (for the results, see Pilot Study section). In the following section we will briefly describe the recruitment stage manipulations (T2 to T4). A comprehensive overview of the material used, including the job advertisement (T1), can be found in the Appendix. Recruitment Stage Manipulations (T2 to T4) Fair vs. unfair treatment (T2). Based on findings relating to fairness in recruitment processes (Bauer et al., 2001; Colquitt, 2001; Gilliland & Steiner, 2012), two different scenarios were created to manipulate the first independent variable in the recruitment process. In the fair condition, the assessment process, which involved a job interview and an ability test, was described according to the rules of justice (e.g., selection information, opportunity to demonstrate one’s abilities). In the unfair condition, violations of the rules of justice occurred (e.g., lack of information, no opportunity to demonstrate one’s abilities). We used a job interview because it has the highest favorability among applicants (Hausknecht, 2013). The ability test was chosen because of its high predictability for job performance (Cook, 2016). All the manipulations were identical in terms of the word count. Positive vs. negative re-evaluation (T3). The manipulation of re-evaluation was inspired by examples from Jones and Skarlicki (2013). In both conditions, participants were instructed in the same way (see the Appendix). Re-evaluation was manipulated to a “negative” condition when the arguments provided emphasized the unfairness of the organization (e.g., the personnel were unqualified and less capable, having a fair and respectful interaction with applicants was unimportant to the company, and relevant legal requirements and regulations relating to the recruitment process were ignored). It was manipulated to a “positive” condition when the arguments provided emphasized that the organization had acted fairly (i.e., presented an opposite view to that given in the negative re-evaluation condition). The word counts for all the manipulations were identical. Job offer vs. rejection (T4). An official letter from the company was shown to applicants, thanking them for their application and for taking part in the assessment tests. Participants in one group received a job offer, while those in the other group were told that their application had not been successful this year because of the large number of other applications (i.e., rejection). Measure Manipulation check measures. To check whether our manipulations were realistic and showed ‘immersion’ (i.e., being able to put yourself in the situation), we conducted two types of manipulation checks. First, both within the pilot study and the main study, we compared respondents’ perceptions of procedural justice (i.e., Is the process fair?) of the assessment stage (T2) using the 14 items from Colquitt et al.’s (2015) procedural justice scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .90; e.g., “Do those procedures uphold ethical and moral standards?”). Respondents were prompted to rate the items on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (to a very small extent) to 5 (to a very large extent). For the post-assessment stage (T3), we compared respondents’ re-evaluation using the seven items from Spencer and Rupp’s (2009) fairness-related counterfactual thinking scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .99; “I believe the organization could have treated me differently”). Respondents were prompted to rate the items on a five- or seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 or 7 (strongly agree) for the pilot and main study, respectively. For the post-decision stage (T4), we compared respondents’ perceptions of distributive justice (i.e., Is the decision fair?) using the eight items from Colquitt et al.’s (2015) distributive justice scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .93; “Is this outcome justified, given your performance?”). Respondents were prompted to rate the items on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (to a very small extent) to 5 (to a very large extent). Second, we also used a three-item measure in the main study to assess how easily the scenarios could be imagined (adopted from Konradt, Okimoto, et al., 2020). At the end of the experiment participants were asked to respond to the following items: “I could easily put myself in these situations,” “It was easy for me to judge the situations,” and “Imagining the situations was no problem.” All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s a reliability coefficient of the measure was .85. Dependent variable: organizational attractiveness. We measured OA at T1, T2, T3, and T4 using the five-item OA scale proposed by Turban and Keon (1993). A sample item was “I would like to work for the company.” All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s a reliability coefficients of the measure across the stages ranged between .86 (T1) and .96 (T2). Sociodemographic characteristics. To be able to describe our sample sufficiently, we measured several sociodemographic variables, including the participants’ age, sex (0 = male, 1 = female), and education on a scale ranging from 1 (low, general secondary school [Hauptschulabschluss in Germany]) to 6 (high, university degree). Following Evertz et al. (2019), we also assessed their job experience in years, number of job changes, and applications in the last five years. Data Analysis Prior to analyzing our hypotheses, we conducted manipulation checks both within a pilot study and the main study using independent samples t-tests (comparing the experimental groups at T2, T3, and T4) and a one-sample t-test (is the mean of the ease of imagination significantly higher than the midpoint of the scale?). Furthermore, we also conducted mediation analyses to examine whether the incorporation of signaling theory is justified, which would in turn support the validity of our material. We thus examined whether respondents’ perceptions of procedural justice (T2), counterfactual thinking (T3), and perceptions of distributive justice (T4) mediated the relationship between the manipulation and OA in the respective stage. Mediation analyses were performed using the PROCESS macro by Hayes (2017) in SPSS. Bootstrapping with 5,000 samples was employed to compute the confidence intervals and inferential statistics. Effects were deemed significant when the confidence interval did not include zero. To test our hypotheses, we conducted an ANOVA with multiple comparisons. Because the conditions for a parametric analysis (e.g., normal distribution or sphericity) were not met, we employed a distribution-free, two-way (one between- and one within-factor; group and time, respectively), nonparametric mixed ANOVA, with post-hoc multiple comparison in R (R version 4.0.0; R Core Team, 2020), using the ‘nparLD’ package (nonparametric longitudinal data; Noguchi et al., 2012). The use of a robust method will also result in lower Type I error rates and more accurate estimates (Albers et al., 2009; Wilcox, 1998). As the nonparametric mixed ANOVA and post-hoc tests are rank-based methods, we also reported the medians (see Noguchi et al., 2012). To test whether there were differences within groups across time (repeated measures ANOVA), we performed the nonparametric rank-based method and multiple comparisons. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to determine whether there were significant differences in OA between the groups. The robust ANOVA-type statistic (ATS) was calculated to assess group and time effects, and interaction between them (Brunner et al., 1997; Brunner & Puri, 2001). To take account of the increased risk of a Type I error associated with multiple testing, a Bonferroni correction was applied by dividing p-values by the number of comparisons. In line with the recommendations suggested by Tomczak and Tomczak (2014), we calculated the effect size epsilon-squared (ϵ2) for the between-group differences and the effect size r for the within-group differences, and their respective 90% confidence intervals (CI), which indicate significance at a 5% level for one-sided hypotheses. The effect sizes (ES) were interpreted as small (ES < .09), moderate (.09 ≤ ES < .25), or strong (ES ≥ .25) (Cohen et al., 2003; Mangiafico, 2016). Pilot Study In a pilot study, we tested the success of manipulations step by step using three samples. Sample one (pre-assessment stage – assessment stage) consisted of 51 employees (45.1% male, Mage = 21.53, SD = 3.54, 7.8% university degree). The fair scenario was judged to be significantly fairer than the unfair scenario, t(44.91) = 10.50, p < .001. Sample 2 (pre-assessment stage – assessment stage – post-assessment stage) consisted of 64 employees (28.1% male, Mage = 21.13, SD = 3.82, 1.6% university degree). Counterfactual thinking in the positive re-evaluation scenario was significantly lower than in the negative re-evaluation scenario, t(62) = -2.32, p = .023. Sample 3 (pre-assessment stage – assessment stage – post-assessment – post-decision stage) consisted of 34 participants (35.3% male, Mage = 25.03, SD = 6.83, 14.7% university degree). Perceived distributive justice was significantly higher in the job offer scenario than in the rejection scenario, t(31.90) = 4.09, p < .001. The results thus confirmed that our material was valid. Table 1 Means, Medians, Standard Deviations, Reliability Coefficients, and Correlations among Study Variables   Note. N = 194; Md = median; OA = organizational attractiveness; T1 = pre-assessment; T2 = assessment; T3 = post-assessment; T4 = post-decision. 10 = male, 1 = female; 2from 1 (low) to 6 (high); 3-1 = unfair treatment, +1 = fair treatment; 4-1 = negative re-evaluation, +1 = positive re-evaluation; 5-1 = rejection, +1 = job offer. Cronbach’s alpha on the diagonal. *p ≤ .05, **p ≤ .01 (one-tailed). Manipulation Checks in the Main Study First, we examined how easily the scenarios could be imagined. A one-sample t-test showed that the mean score (M = 3.61, SD = .84) was significantly higher than the midpoint of the scale, t(188) = 10.01, p < .001. As cut-off for a minimum of immersion, one person with a value ≤ 1 was excluded from the analyses. Second, we made post-hoc comparisons for the assessment, post-assessment, and post-decision stage. As in the pilot study, the unfair treatment scenario was perceived to be significantly less fair, t(191) = -21.23, p ≤ .001, the negative re-evaluation scenario was associated with higher counterfactual thinking, t(189) = -4.12, p ≤ .001, and a rejection led to significantly lower values of distributive justice, t(187) = -7.92, p ≤ .001. Therefore, the analyses revealed that our manipulations were successful. Finally, we also examined whether respondents’ perceptions of procedural justice (T2), counterfactual thinking (T3), and perceptions of distributive justice (T4) mediate the relationship between the manipulation and OA in the respective stage. The results suggest that procedural justice partially mediated the relationship between the treatment and OA with a standardized indirect effect of .33, 95% bootstrap CI [.22, .44]. Counterfactual thinking also partially mediated the relationship between re-evaluation and OA with a standardized indirect effect of -.23, 95% bootstrap CI [-.33, -.11]. Finally, distributive justice fully mediated the relationship between the hiring decision and OA with a standardized indirect effect of .36, 95% bootstrap CI [.27, .45]. These results suggest that participants make inferences about an employer’s attractiveness based on signals they receive during the recruitment process (e.g., procedural justice), supporting the incorporation of signaling theory and the validity of our material. Preliminary Analyses Table 1 displays descriptive statistics, including the mean, median, standard deviation, and Cronbach’s alpha, and bivariate correlations for all variables across all four points in time. As can be seen, sex (where 0 indicates males and 1 indicates females) is the only applicant-level variable that significantly correlated with OA, although the relationships are heterogenous over time. For example, sex was positively correlated with OA at the pre-assessment stage, while OA at the post-assessment stage and sex were negatively related. Regarding the correlations between OA, the results show that OA at T1 was related only to OA at T2, whereas T2 to T4 were all significantly related. Furthermore, the treatment manipulation in the assessment stage was positively related to OA at all stages, the re-evaluation manipulation in the post-assessment stage was positively related to the subsequent stages, and the selection outcome manipulation was positively related to OA in the post-decision stage. The test statistics of the within-group comparisons (i.e., differences between the preceding and subsequent stage within one experimental group) are presented in Table 2. In contrast, the test statistics of the between-group comparisons (i.e., differences between experimental groups within each stage) are presented in Table 3. To illustrate the differences both within and between the groups, we have also included a line diagram (Figure 1). The diagram presents the medians and relative changes for OA across the entire recruitment process separately for the experimental groups. This results in one group at the first stage (job advertisement), two groups at the second stage (fair x unfair treatment), four groups at the third stage (treatment x re-evaluation), and eight groups at the fourth stage (treatment x re-evaluation x selection outcome). On the left side, the relative change in OA is shown (e.g., there can be a loss of up to 67% between the pre-assessment and the assessment stage). On the right side, the absolute change in the median of OA is shown. We also highlighted where the within-group comparisons were significant, indicated by two asterisks. Additionally, the non-significant between-group comparisons are shown within the boxes. Thus, the groups within each box are not significantly different from each other regarding OA. Table 2 Multiple Within-Group Comparisons after Nonparametric Repeated Measures ANOVA   Note. N = 193; Time 1 = pre-assessment; Time 2 = assessment; Time 3 = post-assessment; Time 4 = post-decision; ATS = ANOVA-type statistic; Sign. = significance; * = difference is significant, Bonferroni-adjusted; r = effect size statistic following non-parametric multiple comparisons for repeated measures. Table 3 Multiple Between-Group Comparisons after Kruskal-Wallis Rank Sum Test   Note. N = 193; fair/unfair = treatment; positive/negative = re-evaluation; offer/rejection = selection outcome; Time 2 = assessment (α = .025); Time 3 = post-assessment (α = .008); Time 4 = post-decision (α = .002); * = difference is significant, Bonferroni-adjusted; ϵ2 = epsilon-squared effect size statistic following Kruskal-Wallis test. Before testing our hypotheses, we tested whether there was an interaction between time (i.e., stage) and group (i.e., experimental condition). The interaction between time and group was statistically significant (ATS = 27.52, df = 14.53, p < .001). Nonparametric repeated measures ANOVA revealed that OA changed significantly across time (ATS = 114.26, df = 2.23, p < .001) and Kruskal-Wallis tests indicated significant differences between groups at each stage of the recruitment process. We thus continued to test our hypotheses. In the following, we will present our results in a hypothesis-centered manner and, accordingly, refer repeatedly to the tables and figure. Figure 1 Within- and Between-Group Effects of Treatment (Fair vs. Unfair), Re-Evaluation (Negative vs. Positive), and Selection Outcome (Job Offer vs. Rejection) on the Organizational Attractiveness (OA) during the Four Stages of the Recruitment Process.   Note. N = 193. The non-significant between-group comparisons are shown within the boxes. Thus, the groups within each box are not significantly different from each other regarding OA. The significant within-group comparisons, i.e., the differences between points in time, are indicated with two asterisks (Bonferroni-adjusted alpha level). On the left side, the relative change in OA is shown (e.g., there can be a loss of up to 60% between the pre-assessment and the assessment stage). On the right side, the absolute change in the median of OA is shown. Hypotheses Testing Fair and unfair treatment (T2, assessment stage). Hypothesis 1 predicted that applicants will perceive the organization that is expected to act fairly as less attractive if they are treated unfairly in the assessment stage compared to applicants who were treated fairly. We thus tested whether OA changes significantly between the post-assessment and assessment stage for applicants that were treated unfairly. Consistent with this hypothesis, post-hoc within-group comparisons (see Table 2) revealed that for applicants who were treated unfairly there was a statistically significant decrease of 67% (see the relative change in Figure 1) in OA from the pre-assessment to the assessment stage (r = .87, 90% CI [.86, .87]). We also demonstrated that there was no statistically significant change in OA from the pre-assessment to the assessment stage for applicants who were treated fairly (r = .15, 90% CI [.02, .31]). We also tested whether this implied difference between both groups at the assessment stage was also statistically significant. There was a statistically significant difference in OA between applicants who received fair vs. unfair treatment at the second stage, and the effect size was large (ϵ2 = .70, 90% CI [.64, .73]; see Figure 1 and Table 3). Therefore, our first hypothesis can be supported. Negative re-evaluation (T3, post-assessment stage). Hypothesis 2a predicted that applicants who have been treated "fairly" in the assessment stage will perceive the organization as less attractive if they "negatively" re-evaluate their experience compared to applicants who have been treated unfairly. Within-group comparisons suggest that a negative re-evaluation after fair treatment had a statistically significant and strong effect in reducing OA by 29% (see the relative change in Figure 1) from the assessment to the post-assessment stage (r = .86, 90% CI [.84, .87]; see Table 2), supporting our hypothesis. We also tested whether the experimental groups (fair x negative vs. unfair x negative) differ at the post-assessment stage in terms of OA. The difference was statistically significant (ϵ2 = .40, 90% CI [.27, .53]; see Table 3). Positive re-evaluation (T3, post-assessment stage). Hypothesis 2b predicted that applicants who have been treated "unfairly" in the previous stage of recruitment will perceive the organization as more attractive if they "positively" re-evaluate their experience compared to applicants who have been treated fairly. Within-group comparisons suggest that a positive re-evaluation after unfair treatment had a statistically significant and strong effect in increasing OA about 15% (see relative change in Figure 1) from the assessment to the post-assessment stage (r = .63, 90% CI [.47, .75]), supporting our hypothesis. We also tested whether the experimental groups (unfair x positive vs. fair x positive) differ at the post-assessment stage in terms of OA. The difference was statistically significant (ϵ2 = .65, 90% CI [.54, .72], see Table 3). Selection outcome (T4, post-decision stage). Hypothesis 3a predicted that OA will "increase" when applicants get a "job offer", regardless of whether they were treated fairly or unfairly or negatively/positively re-evaluated their experience. Within-group comparisons suggest that a job offer only had a statistically significant effect in increasing OA from the post-assessment to the post-decision stage for applicants who were treated "fairly" during the assessment stage; there were strong effect sizes, ranging between r = .59 (90% CI [.33, .77]) for the positive re-evaluation group (4% increase, see the relative change in Figure 1) and r = .80 (90% CI [.67, .87]) for the negative re-evaluation group (24% increase, see the relative change in Figure 1). There was no significant change in OA between the post-assessment and post-decision stage for applicants who were treated "unfairly" in the assessment stage (see Table 2), thus only partially supporting our hypothesis. Hypothesis 3b, which predicted that OA would “decrease” when applicants are “rejected”, regardless of whether they were treated fairly or unfairly at earlier stages or whether they negatively/positively re-evaluated their experience, was largely confirmed. With the exception of one group (unfair treatment x negative re-evaluation x rejection), a rejection had a statistically significant and strong effect in reducing OA by a maximum of 19% (see the relative change in Figure 1) between the post-assessment and the post-decision stage (r ranged between .50 and .74; see Table 2). In addition to the within-group comparisons at T4, we also conducted between-group comparisons to see if there were significant differences between the eight experimental groups at T4. There were statistically significant between-group differences at the post-decision stage (T4), χ2 = 113.7, df = 7, p < .001. Multiple comparisons revealed a heterogeneous picture of between-group differences. In general, OA to applicants who were treated “unfairly” during the test stage did not statistically significant differ in the post-decision stage. Furthermore, there was no difference at the post-decision stage between applicants who were treated “fairly” but “negatively” re-evaluated their experience and received a “rejection” (fair x negative x rejection) and those who were treated “unfairly”. The results are presented in more detail in Figure 1 and Table 3. The strong effect sizes for the significant differences ranged between ϵ2 = .40 (90% CI [.21, .59]) and ϵ2 = .74 (90% CI [.68, .77]). Within-Group Comparisons Over the Entire Recruitment Process To return to the question we posed at the beginning of this article – whether OA lost at any stage can be regained at a later stage and whether OA can be maintained throughout the recruitment process – we examined whether there were statistically significant differences between the pre-assessment (T1) and post-decision stage (T4) in each of the eight experimental groups (within-group comparisons, see Table 2). We thus compared OA at T1 with OA at T4 within each group. All differences in OA were significant, except for those applicants who were treated fairly and received a job offer. For applicants who were treated unfairly but positively re-evaluated their experience and received a job offer OA differed markedly between the first and fourth wave (r = .82, 90% CI [.70, .87]), indicating that only a very small part of the OA lost previously had now been restored (only 24% of the loss could be repaired, see the relative change in Figure 1). On the other hand, a negative re-evaluation by applicants who were treated fairly could be compensated for with a job offer, as indicated by there being no significant differences in OA to those applicants. This study provides new evidence on how strong OA to applicants is affected by the individual and combined effects of fair or unfair treatment, re-evaluation, and selection outcome throughout the recruitment process. We conducted a multiple-segment factorial vignette study to simulate the sequential nature of the recruitment process (i.e., pre-assessment, assessment, post-assessment, and post-decision stages) and examined how OA to applicants was affected by the treatment they received from the organization during the assessment stage (fair vs. unfair treatment during a job interview and ability test), their subsequent cognitive re-evaluation (negative vs. positive re-evaluation), and the eventual outcome (job offer vs. rejection). Findings and Practical Implications The first main finding of our study is that unfair treatment at the assessment stage by an organization that was expected to act fairly led to a significant reduction in OA (67%), whereas fair treatment did not lead to any statistically significant change in OA. This supports the assumptions of the dynamic model of organizational justice (Jones & Skarlicki, 2013) that is based on the fairness heuristic theory (Lind, 2001): people expect to be treated fairly and a violation of those expectations will act as phase-shifting event; in our case, this led to changes in applicants’ attitudes toward the recruiting organization. This is also reflected in the justice as deonance perspective provided by Folger (2001). Accordingly, treating people fairly can be seen as a moral obligation and acting fairly will not trigger any changes in applicants’ reactions. By demonstrating that respondents’ perceptions of procedural justice mediate the relationship between treatment at the assessment stage and OA, we also conclude that an employer’s attractiveness is based, at least in part, on the fairness signals that applicants receive during the recruitment process, supporting the inclusion of signaling theory. To conclude, our study indicates that treating applicants fairly will only preserve the OA but treating applicants unfairly although they expected to be treated fairly will reduce their OA to a considerable extent. How to treat applicants fairly and ensure that OA will be maintained will be discussed at a later point when we also discuss the practical implications for the preceding and subsequent stages. So, if applicants have been treated unfairly and OA has dropped significantly, can OA be regained, and if so, how? A second main finding of this research is that OA lost at an early stage in the process could only be regained to a small extent (only about 24% could be regained) during the later stages, even when applicants positively re-evaluated their experience and/or received a job offer. This finding suggests that the unfair treatment during the assessment stage continues to have an effect during the later stages of the process. Previous work has shown that fairness perceptions formed during the assessment stage can have longer-term effects on job performance, even 18 months after a person has been hired (Konradt et al., 2017). Contrary to the findings of Saks and Uggerslev (2010), who concluded that one or two stages of recruitment that felt less satisfactory to the applicants might be compensated for by subsequent stages that they felt were handled more fairly, the results of our study suggest that organizations cannot necessarily make up ground lost early on in the recruitment process in terms of their OA to applicants. A positive re-evaluation by applicants and/or a subsequent job offer will not be sufficient to fully compensate for the effects of violating fairness perceptions during the assessment stage. Another main finding of the present study is that even when applicants were treated fairly at the assessment stage, a negative re-evaluation and/or rejection led to a decrease in OA to them in the later stages (a reduction of 52%). At the same time, a negative re-evaluation after fair treatment was fully compensated for by receiving a job offer at the next stage. One possible implication of these results is that a negative re-evaluation is particularly significant if applicants do not in the end receive a job offer, and this is true for the majority of applicants. Emphasizing the role of a negative re-evaluation of the recruitment process as a result, for example, through discussing the experience with peers (Jones & Skarlicki, 2013), Geenen et al. (2013) found that peer communication considerably affected applicant reactions. In their practical implications they summarized that organizations should be aware of the vital role of peer communication. The negative thoughts and feelings about unfairness in recruitment expressed by peers can have far-reaching consequences for the organization (Degoey, 2000). Organizations that care about fair and friendly treatment of applicants could encourage their employees to share their experiences with their own recruitment process in an independent forum. The reference to this forum could even become part of an employer branding campaign. Although organizations cannot control what is actually reported about the recruitment process, there are several ways to counteract the effects of negative re-evaluation by applicants – or to prevent it from happening in the first place. One way could be to explain the recruitment process to applicants in an informative and transparent way (both before and after the assessments). Nikolaou and Georgiou (2018) have recently demonstrated how important it is to be informative in, for example, job interviews and to respond to applicants’ questions to prevent negative effects on OA. Basch and Melchers (2019) also showed that explanations can improve applicant reactions toward selection methods, including fairness perceptions and perceived OA. This is also in line with the procedural justice rules proposed by Gilliland (1993; for a meta-analysis see Truxillo et al., 2009), especially with the explanation dimension. A process is well explained when both timely and useful information about upcoming procedures is provided, when decisions are justified, and when the information provided is truthful. Therefore, more and continuous contact with applicants (e.g., provision of information, e-mail updates on status) is important to avoid uncertainty (Ryan & Delany, 2010). Another approach is to have a more informal conversation with the applicants after the assessment stage to understand their point of view and to perhaps challenge their view by providing a different perspective, which is reflected in the two-way communication dimension of the procedural justice rules of Gilliland (1993). According to his justice model, two-way communication is a facet of interpersonal treatment and refers, for example, to the consideration of applicants’ views during the recruitment process. Results from a three-year longitudinal study showed that applicants’ perceptions of procedural fairness pre-assessment and post-assessment were shaped mainly by formal characteristics, such as whether there was a job-related and applicant-oriented assessment process, and to interpersonal treatment – were they treated respectfully, for example, by organizational employees with whom they came into contact (Konradt et al., 2017). This points to the importance for recruiters of communicating job relatedness, allowing individual applicants a chance to perform and an opportunity to be reconsidered, and ensuring there is consistency in administrative procedures (Bauer et al., 2020). In their best practice guide for HR managers directly involved in employee recruitment, Bauer et al. (2020) give specific recommendations for recruitment activities derived from the rules of justice (Gilliland, 1993) and the social validity approach (Schuler, 1993). They aptly summarized that following these recommendations not only elicits positive applicant reactions, but also ensures that the assessment process can identify the best candidates for the job. Finally, the results of our study suggest that in almost all cases (i.e., combinations) a rejection led to a reduction in OA, which corroborates previous research (e.g., Stevens, 2010). As there are usually more applicants invited than selected, rejections cannot be avoided, but HR managers can mitigate this negative effect in several ways. For example, Ryan et al. (2017) concluded on the basis of their empirical study that a key factor in preserving OA is to “manage expectations well by communicating clearly when applicants are likely to hear back” (p. 48), because a negative experience of timeliness would direct an applicant’s reactions to other signals from the organization because it does not allow planning and may increase uncertainty. Furthermore, when HR managers communicate the rejection they should provide constructive and transparent feedback to applicants (e.g., covering areas such as lack of qualifications, opportunities for improvement, selection ratio) (Bauer et al., 2020; McCarthy et al., 2017; Schinkel et al., 2011), which could be useful to them in similar situations in the future and helps them to understand why they have been rejected (Colquitt & Chertkoff, 2002). In addition, HR managers should indicate to applicants whether vacancies will continue to be advertised in the future and that the applicant’s details will be kept on file for future reference (Bauer et al., 2020). In certain instances, another possibility might be to offer an internship (Zhao & Liden, 2011). Thus, the negative effects of a rejection in terms of OA might be reduced to some extent; however, it is unlikely that they can be prevented or removed entirely (Ryan & Delany, 2010). Beside seeking to ensure their recruitment processes are fair, organizations can also take steps to restore OA if things do go wrong at any point in the process (Bauer et al., 2020). The approach of restorative justice involves a dialogue between the recipient (e.g., applicant) and the “wrongdoer” (e.g., HR manager, representatives of the organization, supervisor) and focuses on the values that have been violated (e.g., lack of information, no opportunity to show one’s own abilities) and encourages the wrongdoer to understand the harm done, take responsibility for his or her actions, and apologize to those who have been affected (Cojuharenco et al., 2017; Wenzel et al., 2008). Restorative justice emphasizes inclusiveness, interaction between multiple stakeholders, mutual accountability, transparency, flexibility, and a future orientation (Goodstein & Butterfield, 2015). If we apply these same principles to the issue of unfair recruitment practices, one of the implications of our findings is that the organization should explain the reasons why the rules of justice have been violated at any stage, take responsibility for its actions, and apologize to the applicant concerned. Additionally, it is important to agree on what is needed to repair the damage. If, for example, applicants criticize that they have not had the opportunity to adequately demonstrate their abilities, the organization should apologize and could offer another chance with alternative assessments and ensure that appropriate procedures are used in the future. This would not only give applicants another opportunity to prove themselves but would also show them that their suggestions are taken seriously and could be relevant to future applicants. However, the organization or the HR manager must first realize that they have made a mistake, something which rarely happens. In conclusion, we encourage HR managers to follow the rules of justice to avoid having to take a restorative approach. Limitations and Future Research Although this study makes significant contributions to research and practice, it has some limitations that suggest some important directions for future research. First, we used a policy-capturing approach, in which we presented fictitious scenarios but did not measure actual behavior. In real-life studies the effect sizes are usually smaller than in experimental settings (e.g., Gilliland & Steiner, 2012; Hausknecht et al., 2004; Konradt, Oldeweme, et al., 2020; McCarthy et al., 2017). Consequently, the effect sizes derived from our study are considered to be at the upper boundary of possible effects, while the effects in real settings are typically lower. Second, even though our multiple-segment design allowed for repeated dependent measures, it is not a longitudinal study in the conventional sense that would correspond to the time span of a real-world recruitment process. Although policy-capturing designs are an appropriate method to avoid ethical conflicts arising from fairness violations in real-life settings (Kiker et al., 2019), we suggest testing the results of the present study in observational and longitudinal field studies. We also suggest that future studies systematically manipulate the procedural fairness of the hiring decision (e.g., in the form of feedback). In the present study, we only tested whether a job offer or a rejection (with the standardized rationale that there were a lot of applications and a decision had to be made) affected OA, but we did not systematically test whether, for example, a rejection with or without a rationale would have made a difference. Furthermore, the dynamic model of justice (Jones & Skarlicki, 2013) raises the question of how much inconsistency between expectations and experience affects applicant reactions. Although the present study investigated the extent to which negative deviations from positive expectations during the application stage of the recruitment process leads to changes in OA, we did not vary the expectations of fairness. In his multi-level model, Acikgoz (2019) elaborates on which factors might affect applicants’ expectations during the application stage. He considers organizational-level factors (e.g., symbolic attributes or recruitment activities) as well as applicant-level factors (e.g., applicant characteristics, person-job or person-organization fit) and the interaction between them. Future studies should, for example, examine sex that has been found to moderate effects on individuals’ perception of procedural justice (e.g., Caldwell et al., 2009), and its interaction with time. In our study, we found mixed results regarding the relationship between sex and OA at different time points, highlighting the importance of applicant-level factors in applicant reactions. The proposed model by Acikgoz could serve as a framework for, for example, manipulating expectations and thus applicant reactions, and this multi-level perspective might be a useful addition to the conceptual model of Jones and Skarlicki (2013). Future research should also continue to investigate the linearity of the relationship between fair or unfair treatment and applicants’ reactions, which has important implications for theory and research (Pierce & Aguinis, 2013). Recent findings on perceptions of restorative fairness in an organizational setting challenged the presumption that relationships are linear. Konradt, Okimoto, et al. (2020a) showed non-linear relationships between fair or unfair treatment and perceptions of restorative justice. These findings demonstrated that perceptions of justice followed an exponential curve, indicating that people who felt themselves to have received even a small amount of unfair treatment expected an active attempt to make amends. Applied to our study, this would imply there is a quadratic relationship between applicants’ experiences during the recruitment process und their subsequent attitudes toward the organization. Future studies are thus encouraged to include conditions that enable the short-term and long-term nonlinear effects to be examined. Conclusion The present study used an experimental policy-capturing approach to examine the individual and combined effects of fair or unfair treatment, re-evaluation, and selection outcome on OA to applicants throughout the entire recruitment process. One of the significant findings to emerge from this study is that a reduction in OA to applicants because of unfair treatment they received in the assessment stage could not be fully made good during the subsequent recruitment stages, even when they positively re-evaluated their experience and/or received a job offer. The study also showed that, even for applicants who were treated fairly at the assessment stage, OA decreased during the later stages as a result of a negative re-evaluation and/or rejection. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest Cite this article as: Krys, S. & Konradt, U. (2022). Losing and regaining organizational attractiveness during the recruitment process: A multiple-segment factorial vignette study. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 38(1), 43-58. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2022a4 References |

Cite this article as: Krys, S. and Konradt, U. (2022). Losing and Regaining Organizational Attractiveness During the Recruitment Process: A Multiple-Segment Factorial Vignette Study. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 38(1), 43 - 58. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2022a4

krys@psychologie.uni-kiel.de Correspondence: krys@psychologie.uni-kiel.de (S. Krys).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS